Intermittent Fasting and Probiotics for Gut Microbiota Modulation in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: A Narrative Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Mechanistic Pathways Linking Intermittent Fasting, Gut Microbiota, and Type 2 Diabetess

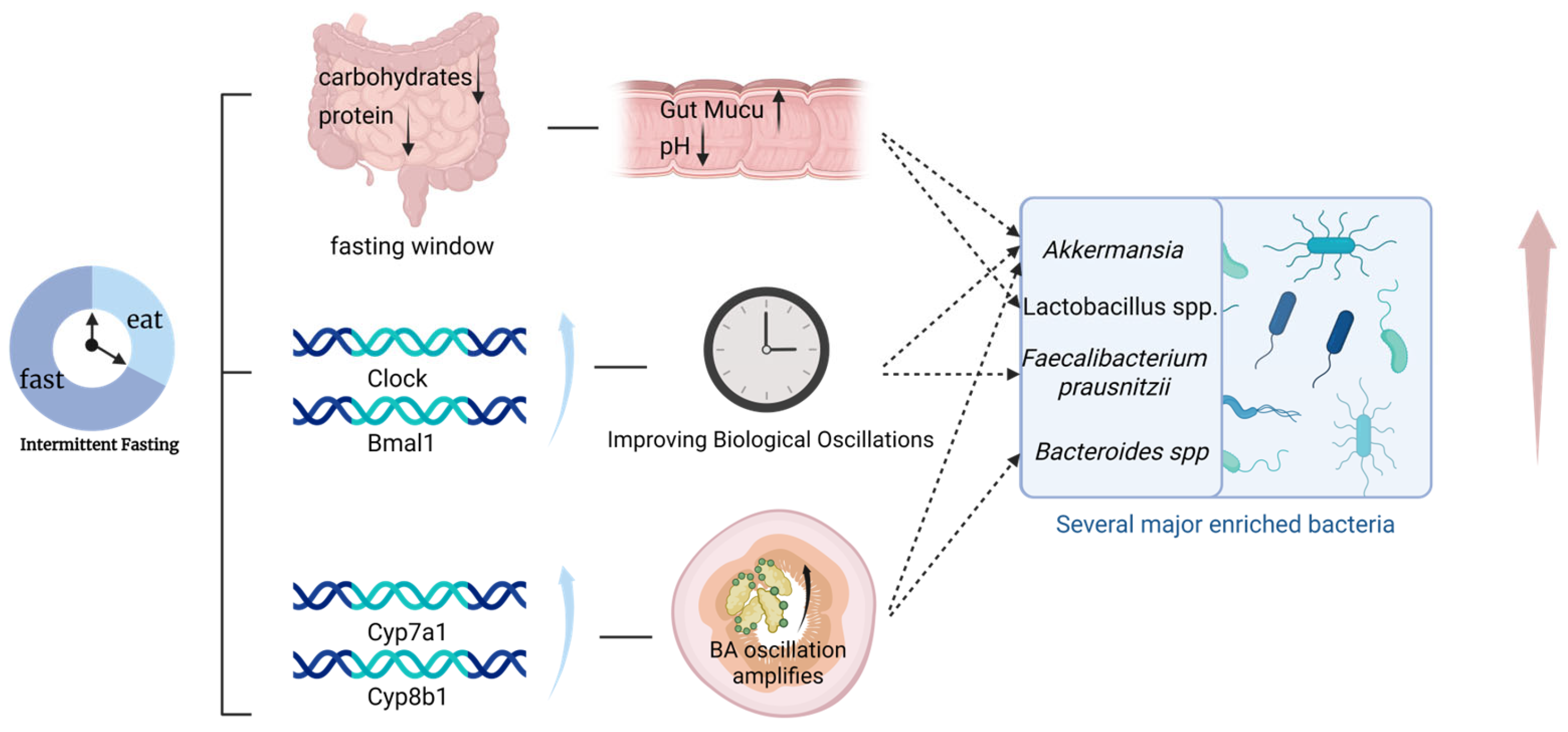

2.1. Altered Substrate Availability and Microbial Selection

2.2. Restoration of Microbial and Host Circadian Oscillations

2.3. Bile Acid Rhythmicity and Host Signaling

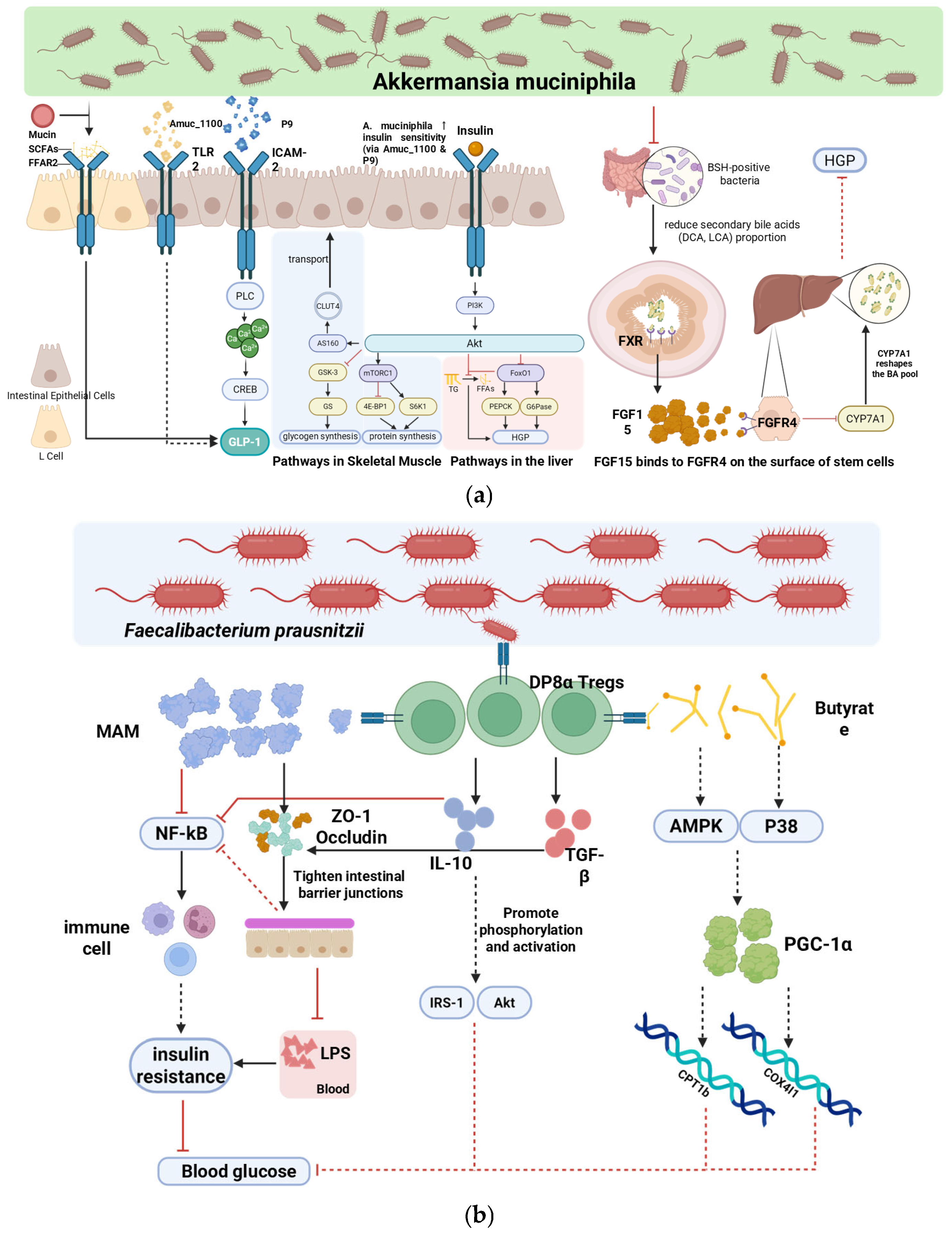

3. Microbiota-Mediated Mechanisms Underlying the Metabolic Benefits of Intermittent Fasting

3.1. Overlapping Mechanisms

3.2. Distinctive Contributions

4. Probiotic-Mediated Modulation of Gut Microbiota in T2DM

4.1. Core Microbiota-Dependent Mechanisms

4.2. Translational Limitations

5. Intermittent Fasting Combined with Probiotics

5.1. Preclinical Evidence Suggesting Potential Interactions

5.2. Clinical Evidence Suggesting Potential Interactions

6. Discussion

6.1. Limitations

6.2. Real-World Feasibility

6.3. Future Directions

- Limited human evidence for combined interventions: Only one small RCT has tested IF with probiotics, showing no additive benefit [17]. Large-scale, adequately powered RCTs are needed to evaluate optimized IF regimens combined with evidence-based multi-strain probiotics.

- Short-term focus and lack of hard endpoints: Most trials are ≤12 weeks and report surrogate markers. Longer-duration studies incorporating hard clinical outcomes (e.g., cardiovascular events, diabetes complications, remission rates) are essential.

- Insufficient causal mechanistic data: Current human findings are largely correlative. Trials should integrate strain-resolved metagenomics, metabolomics, and—where ethical and feasible—tissue-level assessments to establish causality.

- Real-world translation gaps: Adherence, safety, and cost-effectiveness remain underexplored in diverse populations. Pragmatic trials in clinically representative cohorts are required to assess long-term feasibility.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AMP | AMP-activated protein kinase |

| BMAL1 | Brain and muscle Arnt-like 1 |

| BSH | Bile salt hydrolase |

| CREB | cAMP response element-binding protein |

| Cyp7a1 | Cholesterol 7α-hydroxylase |

| eTRE | Early time-restricted eating |

| FFAR2/3 | Free fatty acid receptor 2/3 |

| FXR | Farnesoid X receptor |

| G6Pase | Glucose-6-phosphatase |

| GLP-1 | Glucagon-like peptide-1 |

| GLUT4 | Glucose transporter type 4 |

| HbA1c | Glycated hemoglobin A1c |

| HGP | Hepatic glucose production |

| ICAM-2 | Intercellular adhesion molecule 2 |

| IF | Intermittent fasting |

| IL-10 | Interleukin-10 |

| LPS | Lipopolysaccharide |

| MAM | Microbial anti-inflammatory molecule |

| NF-κB | Nuclear factor kappa B |

| PEPCK | Phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase |

| PI3K | Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase |

| PLC | Phospholipase C |

| PYY | Peptide YY |

| RCT | Randomized controlled trial |

| SCFA | Short-chain fatty acid |

| T2DM | Type 2 diabetes mellitus |

| TGF-β | Transforming growth factor beta |

| TGR5 | Takeda G protein-coupled receptor 5 |

| TLR2 | Toll-like receptor 2 |

| TRF | Time-restricted feeding |

| ZO-1 | Zonula occludens-1 |

References

- Sun, H.; Saeedi, P.; Karuranga, S.; Pinkepank, M.; Ogurtsova, K.; Duncan, B.B.; Stein, C.; Basit, A.; Chan, J.C.N.; Mbanya, J.C.; et al. IDF diabetes atlas: Global, regional and country-level diabetes prevalence estimates for 2021 and projections for 2045. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2022, 183, 109119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chatterjee, S.; Khunti, K.; Davies, M.J. Type 2 diabetes. Lancet 2017, 389, 2239–2251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, Y.; Pedersen, O. Gut microbiota in human metabolic health and disease. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2021, 19, 55–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanders, M.E.; Merenstein, D.J.; Reid, G.; Gibson, G.R.; Rastall, R.A. Probiotics and prebiotics in intestinal health and disease: From biology to the clinic. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2019, 16, 605–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, J.; Li, Y.; Cai, Z.; Li, S.; Zhu, J.; Zhang, F.; Liang, S.; Zhang, W.; Guan, Y.; Shen, D.; et al. A metagenome-wide association study of gut microbiota in type 2 diabetes. Nature 2012, 490, 55–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzullo, P.; Renzo, L.D.; Pugliese, G.; Siena, M.D.; Barrea, L.; Muscogiuri, G.; Colao, A.; Savastano, S., on behalf of Obesity Programs of Nutrition, Education, Research and Assessment (OPERA) Group. From obesity through gut microbiota to cardiovascular diseases: A dangerous journey. Int. J. Obes. Suppl. 2020, 10, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Du, P.; Xu, J.; Wang, W.; Zhang, C. Therapeutic effects of intermittent fasting combined with SLBZS and prebiotics on STZ-HFD-induced type 2 diabetic mice. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Obes. 2024, 17, 4013–4030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Zhang, F.; Ding, X.; Wu, G.; Lam, Y.Y.; Wang, X.; Fu, H.; Xue, X.; Lu, C.; Ma, J.; et al. Gut bacteria selectively promoted by dietary fibers alleviate type 2 diabetes. Science 2018, 359, 1151–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kootte, R.S.; Levin, E.; Salojärvi, J.; Smits, L.P.; Hartstra, A.V.; Udayappan, S.D.; Hermes, G.; Bouter, K.E.; Koopen, A.M.; Holst, J.J.; et al. Improvement of insulin sensitivity after lean donor feces in metabolic syndrome is driven by baseline intestinal microbiota composition. Cell Metab. 2017, 26, 611–619.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlou, V.; Cienfuegos, S.; Lin, S.; Ezpeleta, M.; Ready, K.; Corapi, S.; Wu, J.; Lopez, J.; Gabel, K.; Tussing-Humphreys, L.; et al. Effect of time-restricted eating on weight loss in adults with type 2 diabetes: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw. Open 2023, 6, e2339337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Xiong, H.; Liu, Z.; Liu, X.; Wang, H.; Kou, J.; Yi, D.; Shi, Y.; Wu, H.; Qiao, J. Pasteurized akkermansia muciniphila Timepie001 ameliorates DSS-induced ulcerative colitis in mice by alleviating intestinal injury and modulating gut microbiota. Front. Microbiol. 2025, 16, 1542522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Derrien, M.; van Hylckama Vlieg, J.E.T. Fate, activity, and impact of ingested bacteria within the human gut microbiota. Trends Microbiol. 2015, 23, 354–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hou, Y.; Zhai, X.; Wang, X.; Wu, Y.; Wang, H.; Qin, Y.; Han, J.; Meng, Y. Research progress on the relationship between bile acid metabolism and type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetol. Metab. Syndr. 2023, 15, 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paukkonen, I.; Törrönen, E.-N.; Lok, J.; Schwab, U.; El-Nezami, H. The impact of intermittent fasting on gut microbiota: A systematic review of human studies. Front. Nutr. 2024, 11, 1342787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kho, Z.Y.; Lal, S.K. The human gut microbiome—A potential controller of wellness and disease. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 1835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cani, P.D. Microbiota and metabolites in metabolic diseases. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2019, 15, 69–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tay, A.; Pringle, H.; Penning, E.; Plank, L.D.; Murphy, R. PROFAST: A randomized trial assessing the effects of intermittent fasting and lacticaseibacillus rhamnosus probiotic among people with prediabetes. Nutrients 2020, 12, 3530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Cao, J.; Zhu, M.; Wang, Z.; Jin, Z.; Xiong, Z. Bacteroides fragilis aggravates high-fat diet-induced non-alcoholic fatty liver disease by regulating lipid metabolism and remodeling gut microbiota. Microbiol. Spectr. 2024, 12, e03393-23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Feng, H.; Mao, X.-L.; Deng, Y.-J.; Wang, X.-B.; Zhang, Q.; Guo, Y.; Xiao, S.-M. The effects of probiotics supplementation on glycaemic control among adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised clinical trials. J. Transl. Med. 2023, 21, 442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, D.; Zhao, P.; Gao, J.; Suo, H.; Guo, X.; Han, M.; Zan, X.; Chen, C.; Lyu, X.; Wang, H.; et al. Probiotic supplementation contributes to glycemic control in adults with type 2 diabetes: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Nutr. Res. 2025, 136, 133–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feizollahzadeh, S.; Ghiasvand, R.; Rezaei, A.; Khanahmad, H.; Sadeghi, A.; Hariri, M. Effect of probiotic soy milk on serum levels of adiponectin, inflammatory mediators, lipid profile, and fasting blood glucose among patients with type II diabetes mellitus. Probiotics Antimicrob. Proteins 2017, 9, 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moya-Pérez, A.; Neef, A.; Sanz, Y. Bifidobacterium pseudocatenulatum CECT 7765 reduces obesity-associated inflammation by restoring the lymphocyte-macrophage balance and gut microbiota structure in high-fat diet-fed mice. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0126976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Su, Y.; Li, F.; Wang, Y.; Ma, Z.; Li, Z.; Su, J. The effects of daily fasting hours on shaping gut microbiota in mice. BMC Microbiol. 2020, 20, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Devaux, C.A.; Million, M.; Raoult, D. The butyrogenic and lactic bacteria of the gut microbiota determine the outcome of allogenic hematopoietic cell transplant. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 1642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohamadshahi, M.; Veissi, M.; Haidari, F.; Shahbazian, H.; Kaydani, G.-A.; Mohammadi, F. Effects of probiotic yogurt consumption on inflammatory biomarkers in patients with type 2 diabetes. Bioimpacts 2014, 4, 83–88. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L.; Qin, Q.; Liu, M.; Zhang, X.; He, F.; Wang, G. Akkermansia muciniphila can reduce the damage of gluco/lipotoxicity, oxidative stress and inflammation, and normalize intestine microbiota in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Pathog. Dis. 2018, 76, fty028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cignarella, F.; Cantoni, C.; Ghezzi, L.; Salter, A.; Dorsett, Y.; Chen, L.; Phillips, D.; Weinstock, G.M.; Fontana, L.; Cross, A.H.; et al. Intermittent fasting confers protection in CNS autoimmunity by altering the gut microbiota. Cell Metab. 2018, 27, 1222–1235.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Titchenell, P.M.; Quinn, W.J.; Lu, M.; Chu, Q.; Lu, W.; Li, C.; Chen, H.; Monks, B.R.; Chen, J.; Rabinowitz, J.D.; et al. Direct hepatocyte insulin signaling is required for lipogenesis but is dispensable for the suppression of glucose production. Cell Metab. 2016, 23, 1154–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özkul, C.; Yalınay, M.; Karakan, T. Islamic fasting leads to an increased abundance of akkermansia muciniphila and bacteroides fragilis group: A preliminary study on intermittent fasting. Turk. J. Gastroenterol. 2020, 30, 1030–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, C.; Guarner, F.; Reid, G.; Gibson, G.R.; Merenstein, D.J.; Pot, B.; Morelli, L.; Canani, R.B.; Flint, H.J.; Salminen, S.; et al. The international scientific association for probiotics and prebiotics consensus statement on the scope and appropriate use of the term probiotic. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2014, 11, 506–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Zhong, Y.; Luo, X.M.; Ma, Y.; Liu, J.; Wang, H. Intermittent fasting reshapes the gut microbiota and metabolome and reduces weight gain more effectively than melatonin in mice. Front. Nutr. 2021, 8, 784681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, F.; Guo, Y.; Wang, Y.; Sui, X.; Wang, H.; Zhang, H.; Xin, B.; Yang, C.; Zhang, C.; Jiang, S.; et al. Effects of long-term fasting on gut microbiota, serum metabolome, and their association in Male adults. Nutrients 2025, 17, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ozkul, C.; Yalinay, M.; Karakan, T. Structural changes in gut microbiome after ramadan fasting: A pilot study. Benef. Microbes 2020, 11, 227–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Remely, M.; Hippe, B.; Geretschlaeger, I.; Stegmayer, S.; Hoefinger, I.; Haslberger, A. Increased gut microbiota diversity and abundance of faecalibacterium prausnitzii and akkermansia after fasting: A pilot study. Wien. Klin. Wochenschr 2015, 127, 394–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heddes, M.; Altaha, B.; Niu, Y.; Reitmeier, S.; Kleigrewe, K.; Haller, D.; Kiessling, S. The intestinal clock drives the microbiome to maintain gastrointestinal homeostasis. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 6068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmoll, D.; Walker, K.S.; Alessi, D.R.; Grempler, R.; Burchell, A.; Guo, S.; Walther, R.; Unterman, T.G. Regulation of glucose-6-phosphatase gene expression by protein kinase bα and the forkhead transcription factor FKHR: Evidence for insulin response unit-dependent and -independent effects of insulin on promoter activity. J. Biol. Chem. 2000, 275, 36324–36333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thaiss, C.A.; Zeevi, D.; Levy, M.; Zilberman-Schapira, G.; Suez, J.; Tengeler, A.C.; Abramson, L.; Katz, M.N.; Korem, T.; Zmora, N.; et al. Transkingdom control of microbiota diurnal oscillations promotes metabolic homeostasis. Cell 2014, 159, 514–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leone, V.; Gibbons, S.M.; Martinez, K.; Hutchison, A.L.; Huang, E.Y.; Cham, C.M.; Pierre, J.F.; Heneghan, A.F.; Nadimpalli, A.; Hubert, N.; et al. Effects of diurnal variation of gut microbes and high-fat feeding on host circadian clock function and metabolism. Cell Host Microbe 2015, 17, 681–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarrinpar, A.; Chaix, A.; Yooseph, S.; Panda, S. Diet and feeding pattern affect the diurnal dynamics of the gut microbiome. Cell Metab. 2014, 20, 1006–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.; Bushman, F.D.; FitzGerald, G.A. Rhythmicity of the intestinal microbiota is regulated by gender and the host circadian clock. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 10479–10484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ducastel, S.; Touche, V.; Trabelsi, M.-S.; Boulinguiez, A.; Butruille, L.; Nawrot, M.; Peschard, S.; Chávez-Talavera, O.; Dorchies, E.; Vallez, E.; et al. The nuclear receptor FXR inhibits glucagon-like peptide-1 secretion in response to microbiota-derived short-chain fatty acids. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trabelsi, M.-S.; Daoudi, M.; Prawitt, J.; Ducastel, S.; Touche, V.; Sayin, S.I.; Perino, A.; Brighton, C.A.; Sebti, Y.; Kluza, J.; et al. Farnesoid X receptor inhibits glucagon-like peptide-1 production by enteroendocrine L cells. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 7629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrell, J.M.; Chiang, J.Y. Short-term circadian disruption impairs bile acid and lipid homeostasis in mice. Cell. Mol. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2015, 1, 664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, C.; Xie, C.; Lv, Y.; Li, J.; Krausz, K.W.; Shi, J.; Brocker, C.N.; Desai, D.; Amin, S.G.; Bisson, W.H.; et al. Intestine-selective farnesoid X receptor inhibition improves obesity-related metabolic dysfunction. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 10166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Z.; Chen, H.; Huang, W.; Guo, X.; Yu, L.; Shan, J.; Deng, X.; Liu, J.; Li, W.; Shen, W.; et al. Bacteroides fragilis alleviates necrotizing enterocolitis through restoring bile acid metabolism balance using bile salt hydrolase and inhibiting FXR-NLRP3 signaling pathway. Gut Microbes 2024, 16, 2379566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Xie, C.; Wang, G.; Wu, Y.; Wu, Q.; Wang, X.; Liu, J.; Deng, Y.; Xia, J.; Chen, B.; et al. Gut microbiota and intestinal FXR mediate the clinical benefits of metformin. Nat. Med. 2018, 24, 1919–1929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, H.S.; Cho, C.H.; Yun, M.S.; Jang, S.J.; You, H.J.; Kim, J.; Han, D.; Cha, K.H.; Moon, S.H.; Lee, K.; et al. Akkermansia muciniphila secretes a glucagon-like peptide-1-inducing protein that improves glucose homeostasis and ameliorates metabolic disease in mice. Nat. Microbiol. 2021, 6, 563–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koh, A.; De Vadder, F.; Kovatcheva-Datchary, P.; Bäckhed, F. From dietary fiber to host physiology: Short-chain fatty acids as key bacterial metabolites. Cell 2016, 165, 1332–1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasaly, N.; de Vos, P.; Hermoso, M.A. Impact of bacterial metabolites on gut barrier function and host immunity: A focus on bacterial metabolism and its relevance for intestinal inflammation. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 658354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolhurst, G.; Heffron, H.; Lam, Y.S.; Parker, H.E.; Habib, A.M.; Diakogiannaki, E.; Cameron, J.; Grosse, J.; Reimann, F.; Gribble, F.M. Short-chain fatty acids stimulate glucagon-like peptide-1 secretion via the G-protein–coupled receptor FFAR2. Diabetes 2012, 61, 364–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Mang, Q.; Sun, Y.; Xu, G. Short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) modulate the hepatic glucose and lipid metabolism of coilia nasus via the FFAR/AMPK signaling pathway In vitro. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 3654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scherer, T.; O’Hare, J.; Diggs-Andrews, K.; Schweiger, M.; Cheng, B.; Lindtner, C.; Zielinski, E.; Vempati, P.; Su, K.; Dighe, S.; et al. Brain insulin controls adipose tissue lipolysis and lipogenesis. Cell Metab. 2011, 13, 183–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Effendi, R.M.R.A.; Anshory, M.; Kalim, H.; Dwiyana, R.F.; Suwarsa, O.; Pardo, L.M.; Nijsten, T.E.C.; Thio, H.B. Akkermansia muciniphila and faecalibacterium prausnitzii in immune-related diseases. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 2382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chambers, E.S.; Viardot, A.; Psichas, A.; Morrison, D.J.; Murphy, K.G.; Zac-Varghese, S.E.K.; MacDougall, K.; Preston, T.; Tedford, C.; Finlayson, G.S.; et al. Effects of targeted delivery of propionate to the human colon on appetite regulation, body weight maintenance and adiposity in overweight adults. Gut 2015, 64, 1744–1754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plovier, H.; Everard, A.; Druart, C.; Depommier, C.; Van Hul, M.; Geurts, L.; Chilloux, J.; Ottman, N.; Duparc, T.; Lichtenstein, L.; et al. A purified membrane protein from akkermansia muciniphila or the pasteurized bacterium improves metabolism in obese and diabetic mice. Nat. Med. 2017, 23, 107–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Xu, W.; Wang, R.; Cheng, R.; Tang, Z.; Zhang, M. The outer membrane protein amuc_1100 of akkermansia muciniphila promotes intestinal 5-HT biosynthesis and extracellular availability through TLR2 signalling. Food Funct. 2021, 12, 3597–3610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, W.; Hao, Q.; Qiu, W.; Wen, Y.; Wang, H.; Li, X. Inhibition of NF-κB reduces renal inflammation and expression of PEPCK in type 2 diabetic mice. Inflammation 2018, 41, 2018–2029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarrabayrouse, G.; Bossard, C.; Chauvin, J.-M.; Jarry, A.; Meurette, G.; Quévrain, E.; Bridonneau, C.; Preisser, L.; Asehnoune, K.; Labarrière, N.; et al. CD4CD8αα lymphocytes, a novel human regulatory T cell subset induced by colonic bacteria and deficient in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. PLoS Biol. 2014, 12, e1001833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Touch, S.; Godefroy, E.; Rolhion, N.; Danne, C.; Oeuvray, C.; Straube, M.; Galbert, C.; Brot, L.; Salgueiro, I.A.; Chadi, S.; et al. Human CD4+CD8α+ tregs induced by faecalibacterium prausnitzii protect against intestinal inflammation. JCI Insight 2022, 7, e154722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Liang, Z.; He, Y.; Li, A.; Gao, Y.; Pan, Q.; Cao, J. Pravastatin promotes type 2 diabetes vascular calcification through activating intestinal bacteroides fragilis to induce macrophage M1 polarization. J. Diabetes 2023, 16, e13514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Round, J.L.; Mazmanian, S.K. The gut microbiota shapes intestinal immune responses during health and disease. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2009, 9, 313–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quévrain, E.; Maubert, M.A.; Michon, C.; Chain, F.; Marquant, R.; Tailhades, J.; Miquel, S.; Carlier, L.; Bermúdez-Humarán, L.G.; Pigneur, B.; et al. Identification of an anti-inflammatory protein from faecalibacterium prausnitzii, a commensal bacterium deficient in crohn’s disease. Gut 2016, 65, 415–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hejazi, N.; Ghalandari, H.; Rahmanian, R.; Haghpanah, F.; Makhtoomi, M.; Asadi, A.; Askarpour, M. Effects of probiotics supplementation on glycemic profile in adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus: A grade-assessed systematic review and dose–response meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Clin. Nutr. ESPEN 2024, 64, 133–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kocsis, T.; Molnár, B.; Németh, D.; Hegyi, P.; Szakács, Z.; Bálint, A.; Garami, A.; Soós, A.; Márta, K.; Solymár, M. Probiotics have beneficial metabolic effects in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: A meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 11787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rios-Covian, D.; Gueimonde, M.; Duncan, S.H.; Flint, H.J.; de los Reyes-Gavilan, C.G. Enhanced butyrate formation by cross-feeding between faecalibacterium prausnitzii and bifidobacterium adolescentis. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2015, 362, fnv176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Jeong, Y.; Kang, S.; You, H.J.; Ji, G.E. Co-culture with bifidobacterium catenulatum improves the growth, gut colonization, and butyrate production of faecalibacterium prausnitzii: In vitro and In vivo studies. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Tang, H.; Zhang, C.; Zhao, Y.; Derrien, M.; Rocher, E.; van-Hylckama Vlieg, J.E.T.; Strissel, K.; Zhao, L.; Obin, M.; et al. Modulation of gut microbiota during probiotic-mediated attenuation of metabolic syndrome in high fat diet-fed mice. ISME J. 2015, 9, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabico, S.; Al-Mashharawi, A.; Al-Daghri, N.M.; Wani, K.; Amer, O.E.; Hussain, D.S.; Ahmed Ansari, M.G.; Masoud, M.S.; Alokail, M.S.; McTernan, P.G. Effects of a 6-month multi-strain probiotics supplementation in endotoxemic, inflammatory and cardiometabolic status of T2DM patients: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Clin. Nutr. 2019, 38, 1561–1569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asemi, Z.; Zare, Z.; Shakeri, H.; Sabihi, S.S.; Esmaillzadeh, A. Effect of multispecies probiotic supplements on metabolic profiles, hs-CRP, and oxidative stress in patients with type 2 diabetes. Ann. Nutr. Metab. 2013, 63, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Wang, N.; Yin, B.; Fang, D.; Jiang, T.; Fang, S.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, H.; Wang, G.; Chen, W. Effects of lactobacillus plantarum CCFM0236 on hyperglycaemia and insulin resistance in high-fat and streptozotocin-induced type 2 diabetic mice. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2016, 121, 1727–1736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Sharma, R.K.; Malhotra, S.; Pothuraju, R.; Shandilya, U.K. Lactobacillus rhamnosus NCDC17 ameliorates type-2 diabetes by improving gut function, oxidative stress and inflammation in high-fat-diet fed and streptozotocintreated rats. Benef. Microbes 2017, 8, 243–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaithanya, V.; Kumar, J.; Vajravelu Leela, K.; Ram, M.; Thulukanam, J. Impact of Multistrain Probiotic Supplementation on Glycemic Control in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus—Randomized Controlled Trial. Life 2024, 14, 1484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, R.E.; Sears, D.D. Metabolic effects of intermittent fasting. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 2017, 37, 371–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Xie, C.; Lu, S.; Nichols, R.G.; Tian, Y.; Li, L.; Patel, D.; Ma, Y.; Brocker, C.N.; Yan, T.; et al. Intermittent fasting promotes white adipose browning and decreases obesity by shaping the gut microbiota. Cell Metab. 2017, 26, 672–685.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X. Glucose parameters, inflammation markers, and gut microbiota changes of gut microbiome–targeted therapies in type 2 diabetes mellitus: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2025, 110, 2980–3008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Reference | Type | Intervention | Population/Model | Sample Size | Key Microbiota Changes | Metabolic Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Liu et al. (2024) [7] | Preclinical | IF + SLBZS (prebiotic-like) | STZ-HFD diabetic mice | N = 63 (9/group) | Akkermansiaceae↑; Bifidobacteriaceae↑ | FBG↓; body weight↓; OGTT AUC↓; insulin↑; dyslipidemia↓ |

| Pavlou et al. (2023) [10] | Clinical (RCT) | 8 h TRE (12:00–20:00) | Adults with T2DM and obesity | N = 75 | plasma butyrate↑ | HbA1c↓ (0.9% combined vs.−0.6% IF alone; p = 0.07); GLP-1↓ |

| Tay et al. (2020) [17] | Clinical (RCT) | 5:2 IF (600–650 kcal/day for 2 days/week) + Probiotic (L. rhamnosus HN001) | Adults with prediabetes | N = 26 | (Microbiota composition analysis was not the primary focus of this pilot report) | HbA1c↓ (−2 mmol/mol, p < 0.001) and BW↓ (−5% avg.) in both groups; No additive glycemic benefit from probiotic; Mental health and social functioning in probiotic group↑ (p = 0.007) |

| Li et al. (2023) [19] | Systematic Review & Meta-analysis | Probiotic supplementation (various strains/doses) | Adults with T2DM | 30 RCTs; N = 1827 | Variable enrichment of beneficial taxa | FBG↓ (SMD: −0.37, p < 0.001); HbA1c↓ (SMD: −0.44, p < 0.001); Insulin↓ (SMD: −0.36, p = 0.004); HOMA-IR(SMD: −0.47, p < 0.001)↓. |

| Ma et al. (2025) [20] | Clinical (Network Meta) | Probiotics (multi vs. single-strain) | Adults with T2DM | 30 RCTs; N = 1861 | Multi-strain superior for beneficial shifts | The LAC+BIF+STR combination shows the greatest overall superiority in the cluster analysis of FPG, HbA1c, insulin, and HOMA-IR. |

| Li et al. (2020) [23] | Preclinical | Daily fasting (12, 16, or 20 h) for 1 month | Healthy male C57BL/6J mice | N = 60 (15/group) | Akkermansia↓ (only in 16 h group); Alistipes ↓(only in 16 h group); Changes reversible after cessation | Cumulative food intake↓ (16 & 20 h groups); No significant weight change relative to control. |

| Özkul et al. (2019) [29] | Clinical (Pilot) | Islamic Fasting (Ramadan); ~17 h daily fasting for 29 days | Healthy subjects | N = 9 | Akkermansia muciniphila↓; Bacteroides fragilis group↓ | Fasting blood glucose and total cholesterol significantly decreased, with significantly increased abundances of Akkermansia muciniphila and the Bacteroides fragilis group |

| Wu et al. (2025) [32] | Clinical (Observational) | Long-term fasting (10 days, water only or low calorie) | Healthy male adults | N = 13 | Bacteroidetes↓; Firmicutes↓; Akkermansia↑; Faecalibacterium↓; Microbial diversity decreased initially then stabilized | Body weight↓; BM↓I; Blood glucose↓; Triglycerides; Cholesterol↓ |

| Remely et al. (2015) [34] | Clinical (Pilot) | 1-week fasting program (with laxatives) followed by 6-week probiotic intervention | Overweight/Obese adults | N = 13 | Faecalibacterium prausnitzii↑; Akkermansia muciniphila↑; Bifidobacteri↑; Lactobacilli↑ | Body weight↓; BM↓; Significant correlation between microbial enrichment and weight reduction. |

| Hejazi et al. (2024) [63] | Clinical (Meta, dose–response) | Multi-strain probiotics | Adults with T2DM | 32 RCTs, N = 1920 | beneficial microbial metabolites↑ (e.g., SCFAs) and improved gut barrier integrity | FBG↓; HbA1c↓; fasting insulin↓; HOMA-IR↓ |

| Chaithanya et al. (2024) [72] | Clinical (RCT) | Multi-strain probiotic | Adults with T2DM | N = 124 | No unified sequencing; strain composition product-specific | HbA1c↓; HDL-c↑; LDL-c↓; BMI↓ |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zhang, Z.; Wang, S.; Sun, G.; Pan, D. Intermittent Fasting and Probiotics for Gut Microbiota Modulation in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: A Narrative Review. Nutrients 2026, 18, 119. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18010119

Zhang Z, Wang S, Sun G, Pan D. Intermittent Fasting and Probiotics for Gut Microbiota Modulation in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: A Narrative Review. Nutrients. 2026; 18(1):119. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18010119

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Zhiwen, Shaokang Wang, Guiju Sun, and Da Pan. 2026. "Intermittent Fasting and Probiotics for Gut Microbiota Modulation in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: A Narrative Review" Nutrients 18, no. 1: 119. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18010119

APA StyleZhang, Z., Wang, S., Sun, G., & Pan, D. (2026). Intermittent Fasting and Probiotics for Gut Microbiota Modulation in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: A Narrative Review. Nutrients, 18(1), 119. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18010119