Relationship Between Perceived Stress, Midwife Support and Exclusive Breastfeeding Among Polish Mothers

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Setting

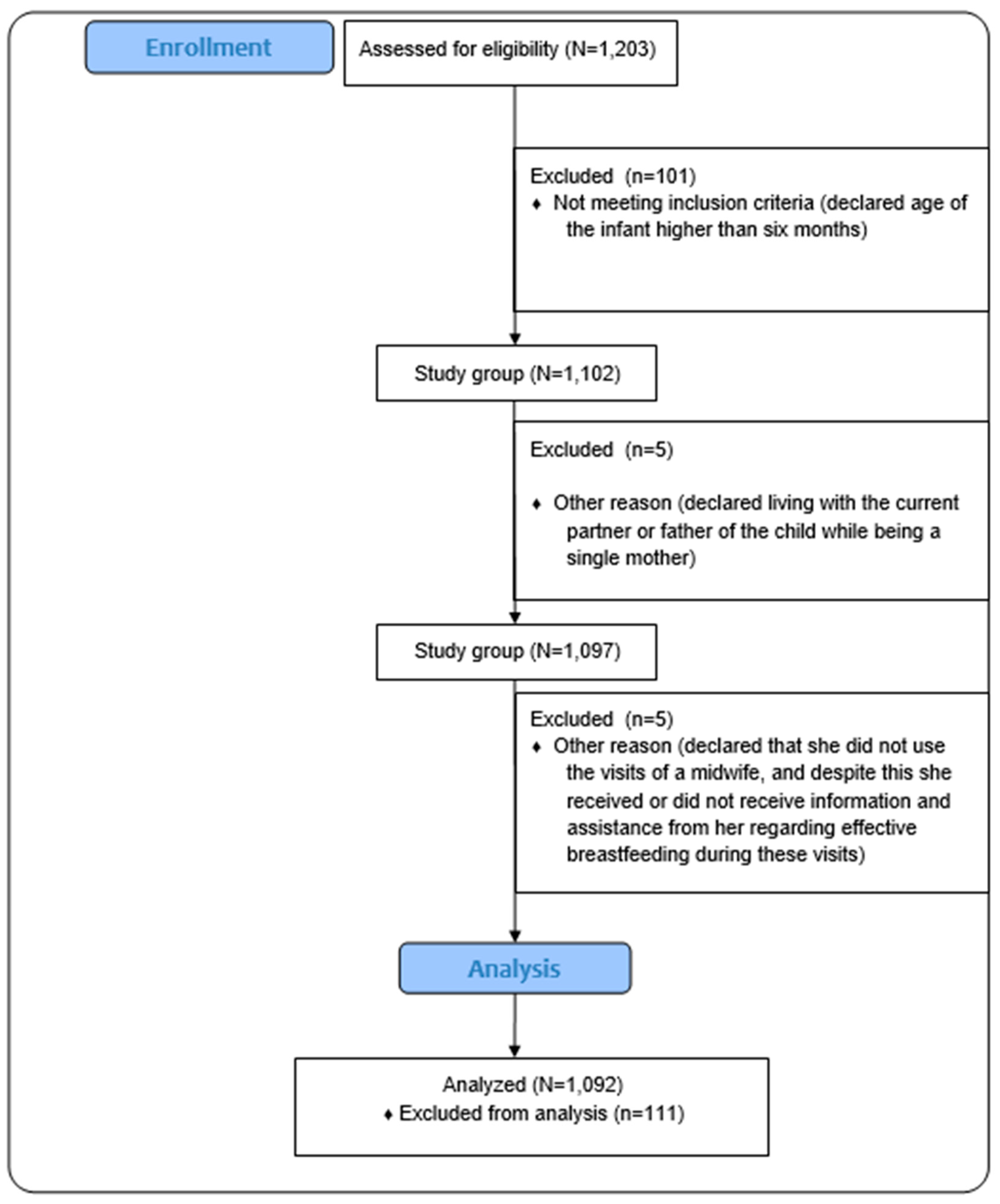

2.2. Participants and Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria

2.2.1. Sample Size Calculation

2.2.2. Recruitment and Initial Sample

2.2.3. Inclusion Criteria

2.2.4. Exclusion Criteria

2.2.5. Final Sample Size

2.3. Data Collection Tools

2.3.1. Demographic and Social Data

2.3.2. Infant Feeding Practices

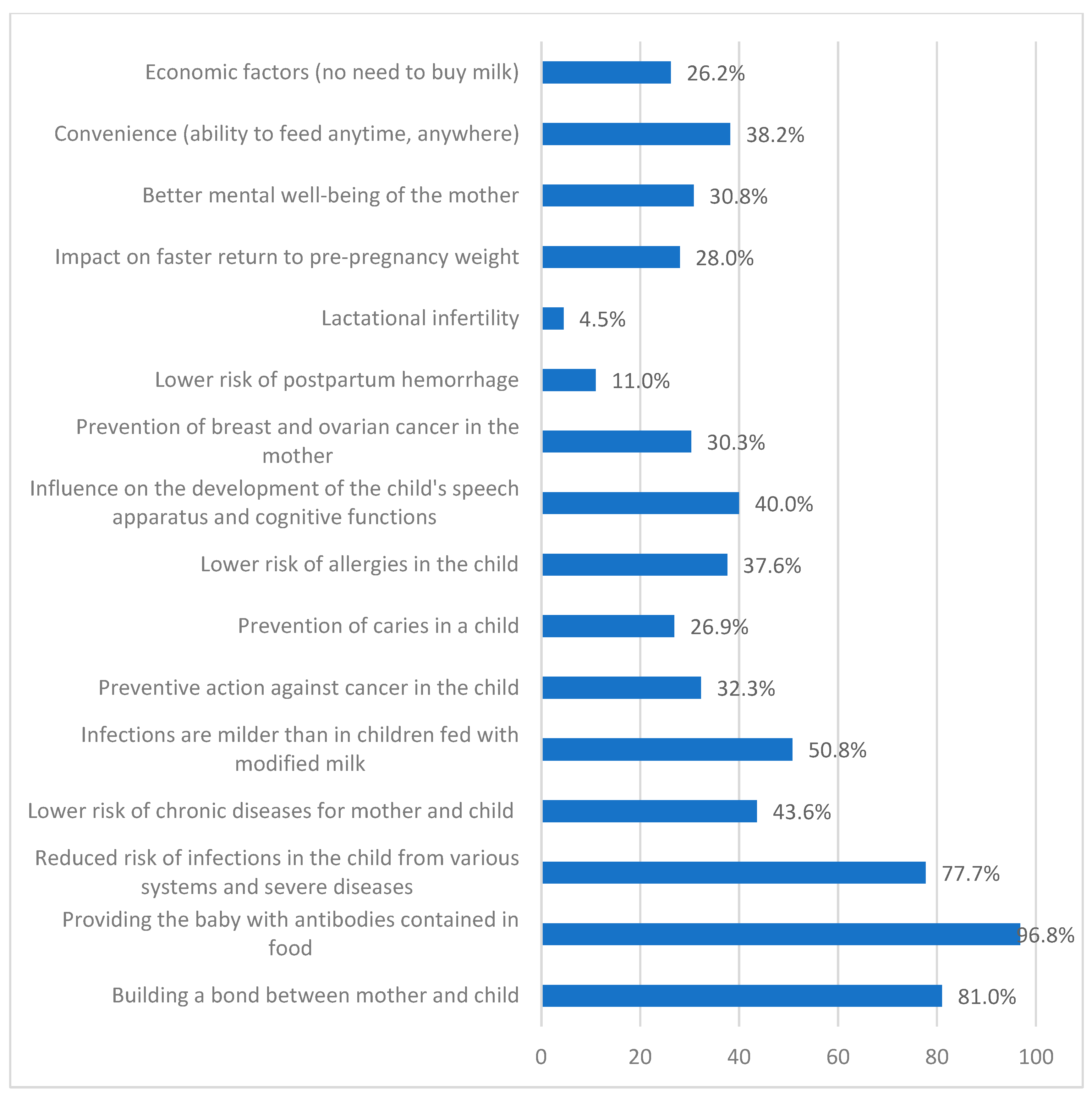

2.3.3. Maternal Opinions and Perceptions

- -

- perceived benefits of breastfeeding (e.g., health benefits for the baby, bonding with the mother, convenience);

- -

- challenges associated with breastfeeding.

2.3.4. Support and Care from Medical Professionals

2.3.5. Perceived Stress Scale (PSS-10)

2.4. Variables

- The dependent variable (DV) was breastfeeding, defined as the actual practice of breastfeeding, including both initiation and continuation. Breastfeeding was categorised as a binary variable: (1) exclusive breastfeeding, meaning the infant received only breast milk without supplementation, and (2) non-exclusive breastfeeding, which included partial breastfeeding (breast milk combined with formula or solid foods) or no breastfeeding at all;

- Breastfeeding support factors: counselling for effective breastfeeding (yes/no), assistance with breastfeeding (yes/no), use of home midwife visits (yes/no), receiving information and assistance from a midwife (yes/no) and use of formula feeding (yes/no);

- Psychological factors: stress levels measured using the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS-10), with higher scores indicating greater perceived stress. This variable was used for determining two groups: women with low or average stress and women with high stress. Scores ranging from 0–13 would be considered low stress. Scores ranging from 14–19 would be assumed as moderate stress. Scores ranging from 20–40 would be viewed as high perceived stress.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

Characteristics of Study Group

4. Discussion

4.1. Limitations

4.2. Further Directions and Implications

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Modak, A.; Ronghe, V.; Gomase, K.P. The Psychological Benefits of Breastfeeding: Fostering Maternal Well-Being and Child Development. Cureus 2023, 15, e46730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rollins, N.C.; Bhandari, N.; Hajeebhoy, N.; Horton, S.; Lutter, C.K.; Martines, J.C.; Piwoz, E.G.; Richter, L.M.; Victora, C.G. Why invest, and what it will take to improve breastfeeding practices? Lancet 2016, 387, 491–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pérez-Escamilla, R.; Tomori, C.; Hernández-Cordero, S.; Baker, P.; Barros, A.J.; Bégin, F.; Chapman, D.J.; Grummer-Strawn, L.M.; McCoy, D.; Menon, P.; et al. Breastfeeding: Crucially important, but increasingly challenged in a market-driven world. Lancet 2023, 401, 472–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vanderlinden, K.; Buffel, V.; Van de Putte, B.; Van de Velde, S. Motherhood in europe: An examination of parental leave regulations and breastfeeding policy influences on breastfeeding initiation and duration. Soc. Sci. 2020, 9, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binns, C.; Lee, M.; Low, W.Y. The Long-Term Public Health Benefits of Breastfeeding. Asia-Pac. J. Public Health 2016, 28, 7–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patnode, C.D.; Henrikson, N.B.; Webber, E.M.; Blasi, P.R.; Senger, C.A.; Guirguis-blake, J.M. Breastfeeding and Health Outcomes for Infants and Children: A Systematic Review. Pediatrics, 2025; Epub ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muro-Valdez, J.C.; Meza-Rios, A.; Aguilar-Uscanga, B.R.; Lopez-Roa, R.I.; Medina-Díaz, E.; Franco-Torres, E.M.; Zepeda-Morales, A.S.M. Breastfeeding-Related Health Benefits in Children and Mothers: Vital Organs Perspective. Medicina 2023, 59, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tschiderer, L.; Seekircher, L.; Kunutsor, S.K.; Peters, S.A.E.; O’Keeffe, L.M.; Willeit, P. Breastfeeding Is Associated With a Reduced Maternal Cardiovascular Risk: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Involving Data From 8 Studies and 1 192 700 Parous Women. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2022, 11, e022746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Breastfeeding. Available online: https://www.who.int/health-topics/breastfeeding#ta (accessed on 27 December 2024).

- Bień, A.; Kulesza-Brończyk, B.; Przestrzelska, M.; Iwanowicz-Palus, G.; Ćwiek, D. The attitudes of polish women towards breastfeeding based on the iowa infant feeding attitude scale (Iifas). Nutrients 2021, 13, 4338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bień, A.; Sierocińska-Mazurek, A.; Ćwiek, D.; Kulesza-Brończyk, B. Czynniki warunkujące postawy kobiet wobec karmienia piersią ocenione na podstawie kwestionariusza The Iowa Infant Feeding Attiude Scale. Gen. Med. Heal. Sci. Ogólna i Nauk. o Zdrowiu. 2022, 28, 326–332. [Google Scholar]

- Królak-Olejnik, B.; Szczygieł, A.; Asztabska, K. Dlaczego Wskaźniki Karmienia Piersią w Polsce są aż tak Niskie? Co i jak Należałoby Poprawić? Cz. 1. Pediatr Interdyscyplinarna. 2018, 21. Available online: https://forumpediatrii.pl/artykul/dlaczego-wskazniki-karmienia-piersia-w-polsce-sa-az-tak-niskie-co-i-jak-nalezaloby-poprawic-cz-1 (accessed on 28 December 2024).

- Krawczyk, A.; Czerwińska-Osipiak, A.; Szablewska, A.W.; Rozmarynowska, W. Psychosocial Factors Influencing Breastmilk Production in Mothers After Preterm Birth: The Role of Social Support in Early Lactation Success-A Cross-Sectional Study. Nutrients 2024, 16, 3883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNICEF. Progress in the Fight for Global Food Security: The Number of Newborns Being Breastfed Is on the Rise. Available online: https://centrum-prasowe.unicef.pl/339428-postep-w- (accessed on 29 December 2024).

- Theurich, M.A.; Davanzo, R.; Busck-Rasmussen, M.; Díaz-Gómez, N.M.; Brennan, C.; Kylberg, E.; Bærug, A.; McHugh, L.; Weikert, C.; Abraham, K.; et al. Breastfeeding Rates and Programs in Europe: A Survey of 11 National Breastfeeding Committees and Representatives. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2019, 68, 400–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO. Global Nutrition Targets 2025: Breastfeeding Policy Brief. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-NMH-NHD-14.7 (accessed on 29 December 2024).

- Victora, C.G.; Bahl, R.; Barros, A.J.D.; Franca, G.V.A.; Horton, S.; Krasevec, J.; Murch, S.; Sankar, M.J.; Walker, N.; Rollins, N.C.; et al. Breastfeeding in the 21st century: Epidemiology, mechanisms, and lifelong effect. Lancet 2016, 387, 475–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Barriers to Breastfeeding: Supporting Initiation and Continuation of Breastfeeding: ACOG Committee Opinion Summary, Number 821. Obstet. Gynecol. 2021, 137, 396–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoff, C.E.; Movva, N.; Rosen Vollmar, A.K.; Pérez-Escamilla, R. Impact of Maternal Anxiety on Breastfeeding Outcomes: A Systematic Review. Adv. Nutr. 2019, 10, 816–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Islami, M.J.; Broidy, L.; Baird, K.; Rahman, M.; Zobair, K.M. Early exclusive breastfeeding cessation and postpartum depression: Assessing the mediating and moderating role of maternal stress and social support. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, D.S.; Pundir, P.; Dhyani, V.S.; Krishnan, J.B.; Parsekar, S.S.; D’souza, S.M.; Ravishankar, N.; Renjith, V. A mixed-methods systematic review on barriers to exclusive breastfeeding. Nutr. Health. 2020, 26, 323–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, W.Q.; Molinaro, A. Maternal obesity adversely affects early breastfeeding in a multicultural, multi-socioeconomic Melbourne community. Aust. N. Z. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2021, 61, 78–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Cheng, G.; Pan, J. Socioeconomic status and breastfeeding in China: An analysis of data from a longitudinal nationwide household survey. BMC Pediatr. 2019, 19, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. Obesity and Overweight. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/o (accessed on 28 December 2024).

- World Health Organization. Global Strategy on Diet, Physical Activity and Health. 2019. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9241592222 (accessed on 28 December 2024).

- Główny Urząd Statystyczny. Stan Zdrowia Ludności Polski w 2019. 2019. Available online: https://stat.gov.pl/obszary-tematyczne/zdrowie/zdrowie/stan-zdrowia-ludnosci-polski-w-2019-r-,26,1.html (accessed on 28 December 2024).

- von Elm, E.; Altman, D.G.; Egger, M.; Pocock, S.J.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Vandenbroucke, J.P. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) Statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies. Int. J. Surg. 2014, 12, 1495–1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Główny Urząd Statystyczny. Rocznik Demograficzny 2023 [Demographic Yearbook 2023]; Statistics Poland: Warsaw, Poland, 2023. Available online: https://stat.gov.pl/obszary-tematyczne/roczniki-statystyczne/roczniki-statystyczne/rocznik-demograficzny-2023,3,17.html (accessed on 20 September 2024).

- Minister Zdrowia. ROZPORZĄDZENIE MINISTRA ZDROWIA1) z Dnia 16 Sierpnia 2018 r. w Sprawie Standardu Organizacyjnego Opieki Okołoporodowej. 11 Września 2018 r 2018 p. 21. Available online: https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/DocDetails.xsp?id=WDU20180001756 (accessed on 28 December 2024).

- Jurczyński, Z.; Ogińska-Bulik, N. NPSR Narzędzia Pomiaru Stresu i Radzenia Sobie ze Stresem; Psychological Test Laboratory of the Polish Psychological Association (Pracownia Testów Psychologicznych PTP): Warsaw, Poland, 2012; 20p. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, S.; Williamson, G. Perceived stress in a probability sample of the United States. In The Social Psychology of Health: Claremont Symposium on Applied Social Psychology; Spacapan, S., Oskamp, S., Eds.; Sage: Newburry Park, CA, USA, 1988; pp. 31–67. [Google Scholar]

- Nagel, E.M.; Howland, M.A.; Pando, C.; Stang, J.; Mason, S.M.; Fields, D.A.; Demerath, E.W. Maternal Psychological Distress and Lactation and Breastfeeding Outcomes: A Narrative Review. Clin. Ther. 2022, 44, 215–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purkiewicz, A.; Regin, K.J.; Mumtaz, W. Breastfeeding: The Multifaceted Impact on Child Development and Maternal Well-Being. Nutrients 2025, 17, 1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Isiguzo, C.; Mendez, D.D.; Demirci, J.R.; Youk, A.; Mendez, G.; Davis, E.M.; Documet, P. Stress, social support, and racial differences: Dominant drivers of exclusive breastfeeding. Matern. Child Nutr. 2023, 19, e13459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szajewska, H.; Socha, P.; Horvath, A.; Rybak, A.; Zalewski, B.M.; Nehring-Gugulska, M.; Gajewska, D.; Helwich, E. Nutrition of healthy term infants. Recommendations of the Polish Society for Paediatrics Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition. Stand. Med. Pediatr. 2021, 18, 7–24. [Google Scholar]

- Ames, S.R.; Lotoski, L.C.; Azad, M.B. Comparing early life nutritional sources and human milk feeding practices: Personalized and dynamic nutrition supports infant gut microbiome development and immune system maturation. Gut Microbes. 2023, 15, 2190305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horta, B.L.; de Lima, N.P. Breastfeeding and Type 2 Diabetes: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Curr. Diab. Rep. 2019, 19, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czupryniak, L.; Gałązka-Sobotka, M.; Kowalska-Bobko, I.; Małecki, M.; Mamcarz, A.; Pawłowska, M.; Pętka, N.; Polak, M.; Nowak-Zając, K.; Zamarlik, M. Szkoła, Gmina, System-Partnerstwo Przeciw Epidemii Otyłości i Cukrzycy: Raport 2022; Uczelnia Łazarskiego w Warszawie: Warsaw, Poland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. Essential Nutrition Actions: Mainstreaming Nutrition Through the Life-Course. 2019. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241515856 (accessed on 27 April 2025).

- Roldão, C.; Lopes, R.; Silva, J.M.; Neves, N.; Gomes, J.C.; Gavina, C.; Taveira-Gomes, T. Can Breastfeeding Prevent Long-Term Overweight and Obesity in Children? A Population-Based Cohort Study. Nutrients 2024, 16, 2728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horta, B.L.; Rollins, N.; Dias, M.S.; Garcez, V.; Pérez-Escamilla, R. Systematic review and meta-analysis of breastfeeding and later overweight or obesity expands on previous study for World Health Organization. Acta Paediatr. 2023, 112, 34–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maliszewska, K.M.; Bidzan, M.; Świątkowska-Freund, M.; Preis, K. Socio-demographic and psychological determinants of exclusive breastfeeding after six months postpartum—A Polish case-cohort study. Ginekol Pol. 2018, 89, 153–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolmaga, A.; Dems-Rudnicka, K.; Garus-Pakowska, A. Attitudes and Barriers of Polish Women towards Breastfeeding—Descriptive Cross-Sectional On-Line Survey. Healthcare 2024, 12, 1744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dagla, M.; Mrvoljak-Theodoropoulou, I.; Vogiatzoglou, M.; Giamalidou, A.; Tsolaridou, E.; Mavrou, M.; Dagla, C.; Antoniou, E. Association between Breastfeeding Duration and Long-Term Midwifery-Led Support and Psychosocial Support: Outcomes from a Greek Non-Randomized Controlled Perinatal Health Intervention. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swerts, M.; Westhof, E.; Bogaerts, A.; Lemiengre, J. Supporting breast-feeding women from the perspective of the midwife: A systematic review of the literature. Midwifery 2016, 37, 32–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McFadden, A.; Gavine, A.; Renfrew, M.J.; Wade, A.; Buchanan, P.; Taylor, J.L.; Veitch, E.; Rennie, A.M.; Crowther, S.A.; Neiman, S.; et al. Support for healthy breastfeeding mothers with healthy term babies. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017, 2, CD001141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhu, Y.; Zhang, L.; Wan, H. What factors influence exclusive breastfeeding based on the theory of planned behaviour. Midwifery 2018, 62, 177–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rozensztrauch, A.; Klaniewska, M.; Berghausen-Mazur, M. Factors affecting the mother’s choice of infant feeding method in Poland: A cross-sectional preliminary study in Poland. Ir. J. Med. Sci. 2022, 191, 1735–1743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suárez-Cotelo, M.D.C.; Movilla-Fernández, M.J.; Pita-García, P.; Arias, B.F.; Novío, S. Breastfeeding knowledge and relation to prevalence. Rev. Esc Enferm. USP 2019, 53, e03433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komitet Upowrzechniania Karmienia Piersią (Committee for the Promotion of Breastfeeding). Lista Szpitali Przyjaznych Dziecku w Polsce (List of Child Friendly Hospitals in Poland). Available online: https://laktacja.pl/article/94,lista-szpitali-w-po (accessed on 3 April 2025).

- Available online: https://stat.gov.pl/files/gfx/portalinformacyjny/pl/defaultaktualnosci/6494/2/1/1/ludnosc_wedlug_cech_spolecznych_-_wyniki_wstepne_nsp_2021.pdf (accessed on 3 April 2025).

- Szablewska, A.W.; Michalik, A.; Czerwińska-Osipiak, A.; Zdończyk, S.A.; Śniadecki, M.; Bukato, K.; Kwiatkowska, W. Breastfeeding vs. Formula Feeding and Maternal Sexuality among Polish Women: A Preliminary Report. Healthcare 2023, 12, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Description |

|---|---|

| Feeding method | Exclusive breastfeeding, mixed feeding, formula feeding |

| Duration of exclusive breastfeeding | Reported in weeks |

| Frequency of breastfeeding | Number of breastfeeding sessions in 24 h |

| Frequency of formula feeding | Number of formula feeding sessions in 24 h |

| Characteristics | No. | % |

|---|---|---|

| Respondents | 1092 | 100 |

| Age | ||

| <25 | 102 | 9.3 |

| 26–35 | 848 | 77.7 |

| 36–45 | 142 | 13.0 |

| Education level | ||

| Primary education | 1 | 0.1 |

| Secondary education | 172 | 15.8 |

| Higher education (Bachelor’s/Master’s Degree) | 900 | 82.4 |

| Vocational education | 19 | 1.7 |

| Place of residence | ||

| Village | 252 | 23.1 |

| City < 50 k inhabitants | 181 | 16.6 |

| City 50–150 k inhabitants | 161 | 14.7 |

| City 150–500 k inhabitants | 180 | 16.5 |

| City > 500 k inhabitants | 318 | 29.1 |

| Marital status | ||

| Single | 70 | 6.4 |

| Marriage/Partnership | 1011 | 92.6 |

| Divorced | 11 | 1.0 |

| Living with the current partner/child’s father | ||

| Yes | 1079 | 98.8 |

| No | 13 | 1.2 |

| Financial situation | ||

| Very good | 336 | 30.8 |

| Good | 528 | 48.4 |

| Satisfactory | 214 | 19.6 |

| Bad | 10 | 0.9 |

| Very bad | 4 | 0.4 |

| Professional activity | ||

| Yes | 857 | 78.5 |

| No | 235 | 21.5 |

| Housing conditions | ||

| Very good | 598 | 54.8 |

| Good | 424 | 38.8 |

| Satisfactory | 64 | 5.9 |

| Bad | 6 | 0.5 |

| Very bad | 0 | 0 |

| Parity | ||

| 1 | 765 | 70.1 |

| 2 | 280 | 25.6 |

| 3 | 40 | 3.7 |

| 4 | 5 | 0.5 |

| 5 or more | 2 | 0.2 |

| Counselling for effective breastfeeding | ||

| Yes | 457 | 41.8 |

| No | 635 | 58.2 |

| Assistance in proper breastfeeding | ||

| Yes | 521 | 47.7 |

| No | 571 | 52.3 |

| Use of midwife visits at home | ||

| Yes | 968 | 88.6 |

| No | 124 | 11.4 |

| Receiving information and assistance from midwife | ||

| Yes | 613 | 56.1 |

| No | 479 | 43.9 |

| Level of perceived stress | ||

| Low | 235 | 21.5 |

| Moderate | 412 | 37.7 |

| High | 445 | 40.8 |

| Variables | Grouping of Variables | Crude OR | Adjusted OR | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | p | OR | 95% CI | p | ||

| Counselling for effective breastfeeding | No | 1.000 | 0.427 | 1.000 | 0.790 | ||

| Yes | 0.852 | 0.573–1.265 | 1.085 | 0.595–1.976 | |||

| Assistance in proper breastfeeding | No | 1.000 | 0.119 | 1.000 | 0.369 | ||

| Yes | 0.731 | 0.494–1.04 | 0.760 | 0.418–1.382 | |||

| Use of midwife visits at home | No | 1.000 | 0.856 | 1.000 | 0.481 | ||

| Yes | 1.081 | 0.466–2.509 | 1.375 | 0.567–3.333 | |||

| Receiving information and assistance from a midwife | No | 1.000 | 0.125 | 1.000 | 0.059 | ||

| Yes | 0.734 | 0.494–1.090 | 0.654 | 0.421–1.017 | |||

| Variables | Grouping of Variables | Crude OR | Adjusted OR | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | p | OR | 95% CI | p | ||

| Counselling for effective breastfeeding | No | 1.000 | <0.001 | 1.000 | 0.033 | ||

| Yes | 0.272 | 0.157–0.471 | 0.467 | 0.232–0.941 | |||

| Assistance in proper breastfeeding | No | 1.000 | <0.001 | 1.000 | 0.011 | ||

| Yes | 0.259 | 0.153–0.437 | 0.424 | 0.220–0.819 | |||

| Use of midwife visits at home | No | 1.000 | 0.329 | 1.000 | 0.352 | ||

| Yes | 1.859 | 0.535–6.451 | 1.854 | 0.506–6.796 | |||

| Receiving information and assistance from a midwife | No | 1.000 | 0.206 | 1.000 | 0.516 | ||

| Yes | 0.753 | 0.485–1.169 | 0.847 | 0.514–1.397 | |||

| Answers | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| Physical exhaustion | 700 | 64.1 |

| Mental exhaustion | 793 | 72.6 |

| Breast health problems (e.g., soreness, nipple injuries, inflammation) | 831 | 76.1 |

| Bust shape variation | 136 | 12.5 |

| Abnormal shape of warts (e.g., flat, concave warts) | 327 | 29.9 |

| Insufficient or no food | 584 | 53.5 |

| Problems on the part of the child (e.g., inability or unwillingness to suckle, drowsiness at the breast) | 674 | 61.7 |

| Lack of assistance from medical personnel in mastering effective feeding techniques | 714 | 65.4 |

| The need to feed “on demand” or to pump regularly | 340 | 31.1 |

| Taking medications related to the mother’s illness | 307 | 28.1 |

| Willingness to return to work quickly | 228 | 20.9 |

| Addictions: nicotinism, alcoholism | 206 | 18.9 |

| Total | 5840 | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Czerwińska-Osipiak, A.; Szablewska, A.W.; Karasek, W.; Krawczyk, A.; Jurek, K. Relationship Between Perceived Stress, Midwife Support and Exclusive Breastfeeding Among Polish Mothers. Nutrients 2025, 17, 1573. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17091573

Czerwińska-Osipiak A, Szablewska AW, Karasek W, Krawczyk A, Jurek K. Relationship Between Perceived Stress, Midwife Support and Exclusive Breastfeeding Among Polish Mothers. Nutrients. 2025; 17(9):1573. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17091573

Chicago/Turabian StyleCzerwińska-Osipiak, Agnieszka, Anna Weronika Szablewska, Wiktoria Karasek, Aleksandra Krawczyk, and Krzysztof Jurek. 2025. "Relationship Between Perceived Stress, Midwife Support and Exclusive Breastfeeding Among Polish Mothers" Nutrients 17, no. 9: 1573. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17091573

APA StyleCzerwińska-Osipiak, A., Szablewska, A. W., Karasek, W., Krawczyk, A., & Jurek, K. (2025). Relationship Between Perceived Stress, Midwife Support and Exclusive Breastfeeding Among Polish Mothers. Nutrients, 17(9), 1573. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17091573