“One Size Doesn’t Fit All”: Nutrition Care Needs in Esophageal and Gastric Cancer Survivors—A Qualitative Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Eligibility

2.2. Recruitment

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Participants

- Two individuals (one survivor and one caregiver) did not meet the inclusion criteria as the cancer treatment was completed outside Ireland, and they were not Irish residents.

- Five individuals did not progress to enrolment as they did not respond to the researchers’ phone calls and emails after an initial expression of interest.

3.2. Identified Themes, Subthemes, and Codes

3.2.1. Nutrition-Related Challenges and Complications

3.2.2. Experiences with Dietetic Service

3.2.3. Coping Strategies

4. Discussion

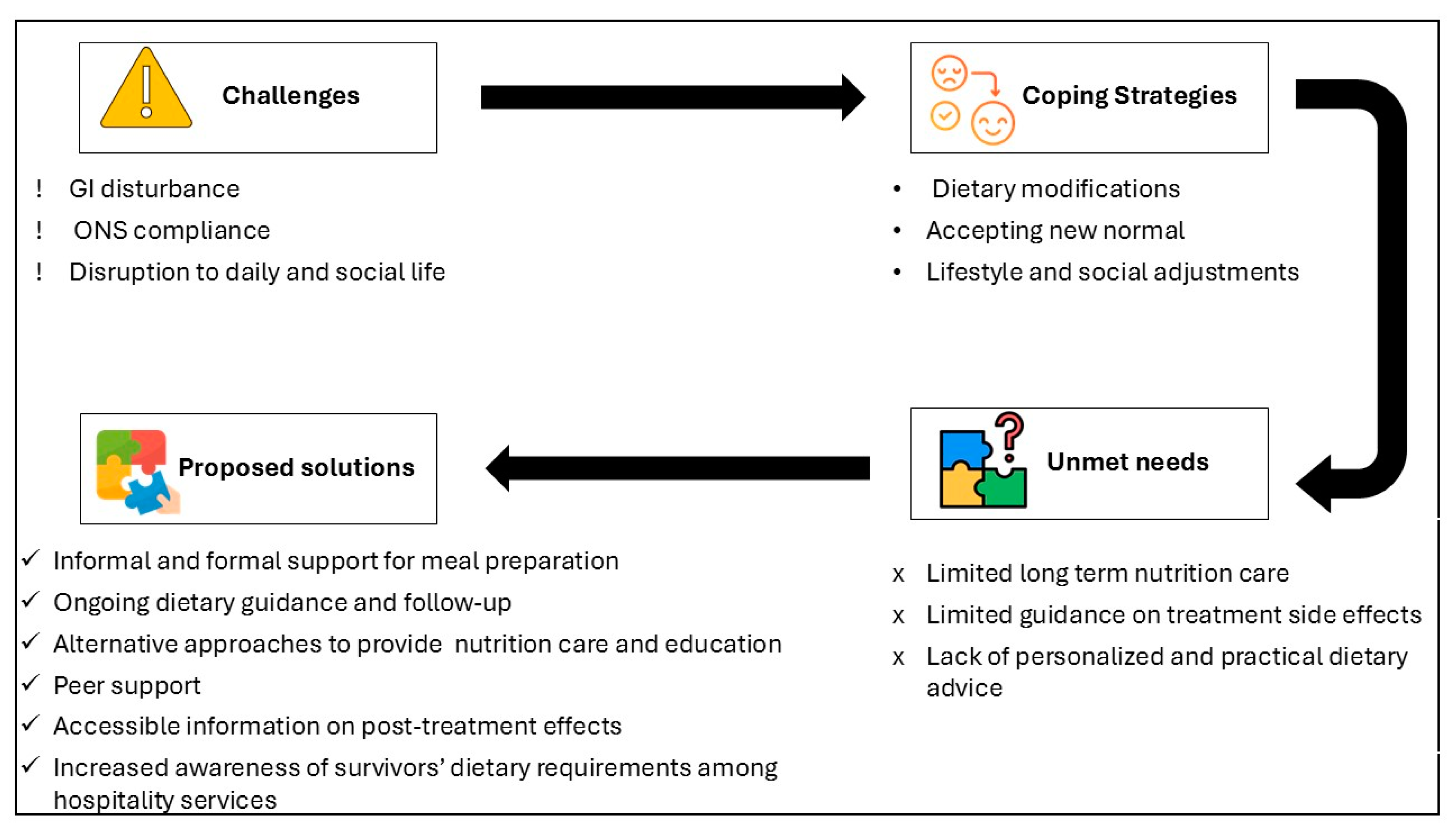

- Cancer survivors continue to experience long-term effects that significantly impact their daily and social lives.

- While dietetic services are available during the acute recovery phase, there is a clear need for more intensive support during this period and extended follow-up care.

- Several unmet nutrition care needs were identified, including limited information on post-treatment complications, a lack of practical and personalized dietary advice, a lack of innovative and interactive education tools, and the necessity for repeated nutrition education.

- Survivors suggested several strategies to manage the adverse effects of treatment, including dietary modifications, acceptance, peer support, and additional resources to assist both survivors and their caregivers.

4.1. Persistent GI Disturbance

4.2. Accessibility and Effectiveness of Dietetic Services

4.3. Resource Limitations and Alternative Approaches

4.4. Reviewing Standard Dietary Advice

4.5. Peer Support

4.6. Support for Carers

4.7. Strength and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| UGI | Upper Gastrointestinal |

| ONS | Oral Nutritional Supplement |

References

- Bray, F.; Laversanne, M.; Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA A Cancer J. Clin. 2024, 74, 229–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Cancer Registry Ireland. Cancer in Ireland 1994–2021: Annual Statistical Report of the National Cancer Registry; NCRI: Cork, Ireland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Arends, J.; Baracos, V.; Bertz, H.; Bozzetti, F.; Calder, P.; Deutz, N.; Erickson, N.; Laviano, A.; Lisanti, M.; Lobo, D. ESPEN expert group recommendations for action against cancer-related malnutrition. Clin. Nutr. 2017, 36, 1187–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heneghan, H.M.; Zaborowski, A.; Fanning, M.; McHugh, A.; Doyle, S.; Moore, J.; Ravi, N.; Reynolds, J.V. Prospective study of malabsorption and malnutrition after esophageal and gastric cancer surgery. Ann. Surg. 2015, 262, 803–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Neill, L.; Moran, J.; Guinan, E.M.; Reynolds, J.V.; Hussey, J. Physical decline and its implications in the management of oesophageal and gastric cancer: A systematic review. J. Cancer Surviv. 2018, 12, 601–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonowicz, S.; Reddy, S.; Sgromo, B. Gastrointestinal side effects of upper gastrointestinal cancer surgery. Best. Pract. Res. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2020, 48–49, 101706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weijs, T.J.; Ruurda, J.P.; Luyer, M.D.P.; Nieuwenhuijzen, G.A.P.; van der Horst, S.; Bleys, R.L.A.W.; van Hillegersberg, R. Preserving the pulmonary vagus nerve branches during thoracoscopic esophagectomy. Surg. Endosc. 2016, 30, 3816–3822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Luo, P.; Xie, H.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, R.; Qin, J.; Seder, C.W.; Kim, M.P.; Flores, R.; Xu, L.; et al. Safety and efficacy of vagus nerve preservation technique during minimally invasive esophagectomy. Ann. Transl. Med. 2022, 10, 336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Na, B.; Kang, C.H.; Na, K.J.; Park, S.; Park, I.K.; Kim, Y.T. Risk Factors of Anastomosis Stricture After Esophagectomy and the Impact of Anastomosis Technique. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2023, 115, 1257–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugase, T.; Miyata, H.; Sugimura, K.; Kanemura, T.; Takeoka, T.; Yamamoto, M.; Shinno, N.; Hara, H.; Omori, T.; Yano, M. Risk factors and long-term postoperative outcomes in patients with postoperative dysphagia after esophagectomy for esophageal cancer. Ann. Gastroenterol. Surg. 2022, 6, 633–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, G.H.; Kang, H.Y.; Choe, E.K. Osteoporosis and fracture after gastrectomy for stomach cancer: A nationwide claims study. Medicine 2018, 97, e0532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mafune, T.; Mikami, S.; Otsubo, T.; Saji, O.; Matsushita, T.; Enomoto, T.; Maki, F.; Tochimoto, S. An Investigation of Factors Related to Food Intake Ability and Swallowing Difficulty After Surgery for Thoracic Esophageal Cancer. Dysphagia 2019, 34, 592–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Konradsson, M.; Nilsson, M. Delayed emptying of the gastric conduit after esophagectomy. J. Thorac. Dis. 2019, 11, S835–S844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, R.; Gu, Q.; Xiao, S.; Zhao, P.; Ding, Z. Patient-reported gastrointestinal symptoms following surgery for gastric cancer and the relative risk factors. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 951485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, V.; Kim, J.; Kim, J.Y.; Raz, D.J.; Merchant, S.; Chao, J.; Chung, V.; Jimenez, T.; Wittenberg, E.; Grant, M.; et al. Dietary alterations and restrictions following surgery for upper gastrointestinal cancers: Key components of a health-related quality of life intervention. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2015, 19, 343–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anandavadivelan, P.; Martin, L.; Djärv, T.; Johar, A.; Lagergren, P. Nutrition Impact Symptoms Are Prognostic of Quality of Life and Mortality After Surgery for Oesophageal Cancer. Cancers 2018, 10, 318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obermannová, R.; Alsina, M.; Cervantes, A.; Leong, T.; Lordick, F.; Nilsson, M.; van Grieken, N.C.T.; Vogel, A.; Smyth, E.C. Oesophageal cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guideline for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann. Oncol. 2022, 33, 992–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaw, R.A.; Nevins, E.J.; Phillips, A.W. Incidence, Diagnosis and Management of Malabsorption Following Oesophagectomy: A Systematic Review. J. Gastrointest. Surg. 2022, 26, 1781–1790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kattlove, H.; Winn, R.J. Ongoing care of patients after primary treatment for their cancer. CA A Cancer J. Clin. 2003, 53, 172–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erickson, N.; Sullivan, E.S.; Kalliostra, M.; Laviano, A.; Wesseling, J. Nutrition care is an integral part of patient-centred medical care: A European consensus. Med. Oncol. 2023, 40, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Carey, S. Translating Evidence-Based Practice Guidelines Into a Summary of Recommendations for the Nutrition Management of Upper Gastrointestinal Cancers. Nutr. Clin. Pr. 2014, 29, 518–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keaver, L.; Yiannakou, I.; Folta, S.C.; Zhang, F.F. Perceptions of Oncology Providers and Cancer Survivors on the Role of Nutrition in Cancer Care and Their Views on the “NutriCare” Program. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caccialanza, R.; Cereda, E.; Pinto, C.; Cotogni, P.; Farina, G.; Gavazzi, C.; Gandini, C.; Nardi, M.; Zagonel, V.; Pedrazzoli, P. Awareness and consideration of malnutrition among oncologists: Insights from an exploratory survey. Nutrition 2016, 32, 1028–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spiro, A.; Baldwin, C.; Patterson, A.; Thomas, J.; Andreyev, H.J.N. The views and practice of oncologists towards nutritional support in patients receiving chemotherapy. Br. J. Cancer 2006, 95, 431–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keaver, L.; Connolly, P.; Richmond, J. Providing nutrition advice in the oncology setting: A survey of current practice, awareness of guidelines and training needs of Irish healthcare professionals in three hospitals. Eur. J. Cancer Care 2021, 30, e13405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Felice, F.; Malerba, S.; Nardone, V.; Salvestrini, V.; Calomino, N.; Testini, M.; Boccardi, V.; Desideri, I.; Gentili, C.; De Luca, R.; et al. Progress and Challenges in Integrating Nutritional Care into Oncology Practice: Results from a National Survey on Behalf of the NutriOnc Research Group. Nutrients 2025, 17, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scotté, F.; Taylor, A.; Davies, A. Supportive Care: The “Keystone” of Modern Oncology Practice. Cancers 2023, 15, 3860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hart, N.H.; Nekhlyudov, L.; Smith, T.J.; Yee, J.; Fitch, M.I.; Crawford, G.B.; Koczwara, B.; Ashbury, F.D.; Lustberg, M.B.; Mollica, M.; et al. Survivorship care for people affected by advanced or metastatic cancer: MASCC-ASCO standards and practice recommendations. Support. Care Cancer 2024, 32, 313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mayo, S.J.; Ajaj, R.; Drury, A. Survivors’ preferences for the organization and delivery of supportive care after treatment: An integrative review. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2021, 54, 102040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, M.K.; Birkelund, R.; Mortensen, M.B.; Schultz, H. Being a relative on the sideline to the patient with oesophageal cancer: A qualitative study across the treatment course. Scand. J. Caring Sci. 2021, 35, 277–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keaver, L. Irish cancer patients and survivors have a positive view of the role of nutritional care in cancer management from diagnosis through survivorship. Ir. J. Med. Sci. 2021, 190, 1387–1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keaver, L.; O’Callaghan, N.; Douglas, P. Nutrition support and intervention preferences of cancer survivors. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 2023, 36, 526–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Callaghan, N.; Douglas, P.; Keaver, L. A qualitative study into cancer survivors’ relationship with nutrition post-cancer treatment. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 2023, 36, 406–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keaver, L.; Richmond, J.; Rafferty, F.; Douglas, P. Sources of nutrition advice and desired nutrition guidance in oncology care: Patient’s perspectives. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 2023, 36, 434–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haahr, M. What’s This Fuss About True Randomness. 2009. Available online: https://www.random.org (accessed on 28 February 2021).

- Loeliger, J.; Dewar, S.; Kiss, N.; Drosdowsky, A.; Stewart, J. Patient and carer experiences of nutrition in cancer care: A mixed-methods study. Support. Care Cancer 2021, 29, 5475–5485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moser, A.; Korstjens, I. Series: Practical guidance to qualitative research. Part 3: Sampling, data collection and analysis. Eur. J. Gen. Pract. 2018, 24, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crowder, S.L.; Najam, N.; Sarma, K.P.; Fiese, B.H.; Arthur, A.E. Head and Neck Cancer Survivors’ Experiences with Chronic Nutrition Impact Symptom Burden after Radiation: A Qualitative Study. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2020, 120, 1643–1653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCorry, N.K.; Dempster, M.; Clarke, C.; Doyle, R. Adjusting to life after esophagectomy: The experience of survivors and carers. Qual. Health Res. 2009, 19, 1485–1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsson, U.; Bosaeus, I.; Bergbom, I. Patients’ Experiences of the Recovery Period 12 Months After Upper Gastrointestinal Surgery. Gastroenterol. Nurs. 2010, 33, 422–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malmström, M.; Ivarsson, B.; Johansson, J.; Klefsgård, R. Long-term experiences after oesophagectomy/gastrectomy for cancer—A focus group study. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2013, 50, 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carey, S.; Laws, R.; Ferrie, S.; Young, J.; Allman-Farinelli, M. Struggling with food and eating—Life after major upper gastrointestinal surgery. Support. Care Cancer Off. J. Multinatl. Assoc. Support. Care Cancer 2013, 21, 2749–2757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clarke, C.; McCorry, N.K.; Dempster, M. The role of identity in adjustment among survivors of oesophageal cancer. J. Health Psychol. 2011, 16, 99–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Callaghan, N.; Douglas, P.; Keaver, L. The persistence of nutrition impact symptoms in cancer survivors’ post-treatment. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2022, 81, E156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pucher, P.H.; Coombes, A.; Evans, O.; Taylor, J.; Moore, J.L.; White, A.; Lagergren, J.; Baker, C.R.; Kelly, M.; Gossage, J.A.; et al. P-OGC21 Patient perspectives on symptoms of importance and preferences for follow-up after major upper gastro-intestinal cancer surgery. Br. J. Surg. 2021, 108, znab430-149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, E.S.; Rice, N.; Kingston, E.; Kelly, A.; Reynolds, J.V.; Feighan, J.; Power, D.G.; Ryan, A.M. A national survey of oncology survivors examining nutrition attitudes, problems and behaviours, and access to dietetic care throughout the cancer journey. Clin. Nutr. ESPEN 2021, 41, 331–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, E.A.; van der Pols, J.C.; Ekberg, S. Needs, preferences, and experiences of adult cancer survivors in accessing dietary information post-treatment: A scoping review. Eur. J. Cancer Care 2021, 30, e13381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Veen, M.R.; Winkels, R.M.; Janssen, S.H.M.; Kampman, E.; Beijer, S. Nutritional Information Provision to Cancer Patients and Their Relatives Can Promote Dietary Behavior Changes Independent of Nutritional Information Needs. Nutr. Cancer 2018, 70, 483–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, A.S.; Steele, R.; Coyle, J. Lifestyle issues for colorectal cancer survivors—Perceived needs, beliefs and opportunities. Support. Care Cancer 2013, 21, 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabacchi, F. Empowerment, Guidance, and Support: Patient-Dietitian Experiences for Upper Gastrointestinal Cancer Remote Consultations. Kompass Nutr. Diet. 2024, 4, 27–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonoi, M.; Noma, K.; Tanabe, S.; Maeda, N.; Shirakawa, Y.; Morimatsu, H. Assessing the Role of Perioperative Nutritional Education in Improving Oral Intake after Oesophagectomy: A Retrospective Study. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2023, 24, 2037–2041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, A.E.; O’Neill, L.; Connolly, D.; Guinan, E.; Boland, L.; Doyle, S.; O’Sullivan, J.; Reynolds, J.V.; Hussey, J. Perspectives of Esophageal Cancer Survivors on Diagnosis, Treatment, and Recovery. Cancers 2020, 13, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- AlleaBelle Gongola, M.; Reif, R.J.; Cosgrove, P.C.; Sexton, K.W.; Marino, K.A.; Steliga, M.A.; Muesse, J.L. Preoperative nutritional counselling in patients undergoing oesophagectomy. J. Perioper. Pr. 2022, 32, 183–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hewko, S.; Oyesegun, A.; Clow, S.; VanLeeuwen, C. High turnover in clinical dietetics: A qualitative analysis. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2021, 21, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irish Nutrition and Dietetic Institute. Submission to the National Cancer Strategy 2016–2025; Irish Nutrition and Dietetic Institute (INDI): Dublin, Ireland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Trujillo, E.B.; Claghorn, K.; Dixon, S.W.; Hill, E.B.; Braun, A.; Lipinski, E.; Platek, M.E.; Vergo, M.T.; Spees, C. Inadequate Nutrition Coverage in Outpatient Cancer Centers: Results of a National Survey. J. Oncol. 2019, 2019, 7462940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelly, J.T.; Allman-Farinelli, M.; Chen, J.; Partridge, S.R.; Collins, C.; Rollo, M.; Haslam, R.; Diversi, T.; Campbell, K.L. Dietitians Australia position statement on telehealth. Nutr. Diet. 2020, 77, 406–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Timon, C.M.; Doyle, S. The nutrition support needs of cancer survivors in Ireland. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2020, 79, E774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muscaritoli, M.; Arends, J.; Bachmann, P.; Baracos, V.; Barthelemy, N.; Bertz, H.; Bozzetti, F.; Hütterer, E.; Isenring, E.; Kaasa, S. ESPEN practical guideline: Clinical Nutrition in cancer. Clin. Nutr. 2021, 40, 2898–2913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Collaborating Centre for Acute Care. Nutrition Support for Adults: Oral Nutrition Support, Enteral Tube Feeding and Parenteral Nutrition; National Collaborating Centre for Acute Care: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- de las Peñas, R.; Majem, M.; Perez-Altozano, J.; Virizuela, J.A.; Cancer, E.; Diz, P.; Donnay, O.; Hurtado, A.; Jimenez-Fonseca, P.; Ocon, M.J. SEOM clinical guidelines on nutrition in cancer patients (2018). Clin. Transl. Oncol. 2019, 21, 87–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galaniha, L.T.; McClements, D.J.; Nolden, A. Opportunities to improve oral nutritional supplements for managing malnutrition in cancer patients: A food design approach. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 102, 254–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogan, S.E.; Solomon, M.J.; Carey, S.K. Exploring reasons behind patient compliance with nutrition supplements before pelvic exenteration surgery. Support. Care Cancer 2019, 27, 1853–1860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fhlannagáin, N.N.; Greaney, C.; Byrne, C.; Keaver, L. A qualitative analysis of nutritional needs and dietary changes during cancer treatment in Ireland. Ir. J. Med. Sci. 2024, 193, 1171–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.-M.; Wang, T.-J.; Huang, C.-S.; Liang, S.-Y.; Yu, C.-H.; Lin, T.-R.; Wu, K.-F. Nutritional Status and Related Factors in Patients with Gastric Cancer after Gastrectomy: A Cross-Sectional Study. Nutrients 2022, 14, 2634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westergren, A. Nutrition and its relation to mealtime preparation, eating, fatigue and mood among stroke survivors after discharge from hospital—A pilot study. Open Nurs. J. 2008, 2, 15–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jablotschkin, M.; Binkowski, L.; Markovits Hoopii, R.; Weis, J. Benefits and challenges of cancer peer support groups: A systematic review of qualitative studies. Eur. J. Cancer Care 2022, 31, e13700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andreassen, S.; Randers, I.; Ternulf Nyhlin, K.; Mattiasson, A.-C. A meta-analysis of qualitative studies on living with oesophageal and clinically similar forms of cancer, seen from the perspective of patients and family members. Int. J. Qual. Stud. Health Well-Being 2007, 2, 114–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baudry, A.-S.; Delpuech, M.; Charton, E.; Hivert, B.; Carnot, A.; Ceban, T.; Dominguez, S.; Lemaire, A.; Aelbrecht-Meurisse, C.; Anota, A.; et al. Association between emotional competence and risk of unmet supportive care needs in caregivers of cancer patients at the beginning of care. Support. Care Cancer 2024, 32, 302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stovall, E.; Greenfield, S.; Hewitt, M. From Cancer Patient to Cancer Survivor: Lost in Transition; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Furtado, M.; Davis, D.; Groarke, J.M.; Graham-Wisener, L. Experiences of informal caregivers supporting individuals with upper gastrointestinal cancers: A systematic review. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2024, 24, 932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Northouse, L.L.; Katapodi, M.C.; Song, L.; Zhang, L.; Mood, D.W. Interventions with Family Caregivers of Cancer Patients: Meta-Analysis of Randomized Trials. CA A Cancer J. Clin. 2010, 60, 317–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opdenakker, R. Advantages and disadvantages of four interview techniques in qualitative research. Forum Qual. Sozialforsch. = Forum Qual. Soc. Res. 2006, 7, art-11. [Google Scholar]

- Enoch, J.; Subramanian, A.; Willig, C. “If I don’t like it, I’ll just pop the phone down!”: Reflecting on participant and researcher experiences of telephone interviews conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic. SSM—Qual. Res. Health 2023, 4, 100351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acocella, I. The focus groups in social research: Advantages and disadvantages. Qual. Quant. 2012, 46, 1125–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeom, J.-W.; Yeom, I.-S.; Park, H.-Y.; Lim, S.-H. Cultural factors affecting the self-care of cancer survivors: An integrative review. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2022, 59, 102165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fenton, A.T.H.R.; Ornstein, K.A.; Dilworth-Anderson, P.; Keating, N.L.; Kent, E.E.; Litzelman, K.; Enzinger, A.C.; Rowland, J.H.; Wright, A.A. Racial and ethnic disparities in cancer caregiver burden and potential sociocultural mediators. Support. Care Cancer 2022, 30, 9625–9633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beatty, L.; Binnion, C.; Kemp, E.; Koczwara, B. A qualitative exploration of barriers and facilitatorsto adherence to an online self-help intervention for cancer-related distress. Support. Care Cancer 2017, 25, 2539–2548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Participant Code | Age | Gender | Cancer Diagnosis | Time Since Surgery (Months) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | 76 | M | Esophageal | 108 |

| P2 | 56 | M | Esophageal | 24 |

| P3 | 63 | M | Esophageal | 24 |

| P4 | 34 | M | Esophageal | 23 |

| P5 | 51 | F | Gastric | 24 |

| P6 | 71 | M | Esophageal | 62 |

| P7 1 | 60 | F | Esophageal | 62 |

| P8 | 62 | F | Gastric | 15 |

| P9 | 58 | M | Esophageal | 112 |

| P10 1 | 50 | F | Esophageal | NA 2 |

| P11 | 70 | M | Esophageal/Gastric | 87/20 |

| P12 1 | 55 | M | Esophageal | NA 2 |

| Theme | Subthemes | Codes |

|---|---|---|

| Nutrition-related challenges and complications | Gastrointestinal related complications | Gastrointestinal symptoms |

| Barriers to ONS compliance | ||

| Impact on individuals’ daily life | Meal preparation and altered meal plans | |

| Limited food choices | ||

| Disturbed daily and social life | ||

| Experiences with dietetic service | Access and effectiveness | Accessibility of dietetic service |

| Effectiveness of dietitian visits | ||

| Continuation and frequency of dietetic follow-up | ||

| Information needs | Tailored and practical dietary advice | |

| What to expect post-treatment | ||

| Additional educational material and methods | ||

| Reiterating dietary advice | ||

| Coping strategies | Practical strategies | Dietary modifications |

| Accepting new normal | ||

| Support for meal preparation | ||

| Consideration for eating out | ||

| Peer and external support | Peer support | |

| Support for carers |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sadeghi, F.; Hussey, J.; Doyle, S.L. “One Size Doesn’t Fit All”: Nutrition Care Needs in Esophageal and Gastric Cancer Survivors—A Qualitative Study. Nutrients 2025, 17, 1567. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17091567

Sadeghi F, Hussey J, Doyle SL. “One Size Doesn’t Fit All”: Nutrition Care Needs in Esophageal and Gastric Cancer Survivors—A Qualitative Study. Nutrients. 2025; 17(9):1567. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17091567

Chicago/Turabian StyleSadeghi, Fatemeh, Juliette Hussey, and Suzanne L. Doyle. 2025. "“One Size Doesn’t Fit All”: Nutrition Care Needs in Esophageal and Gastric Cancer Survivors—A Qualitative Study" Nutrients 17, no. 9: 1567. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17091567

APA StyleSadeghi, F., Hussey, J., & Doyle, S. L. (2025). “One Size Doesn’t Fit All”: Nutrition Care Needs in Esophageal and Gastric Cancer Survivors—A Qualitative Study. Nutrients, 17(9), 1567. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17091567