Evaluation of the Nutritional Education Program in Increasing Nutrition-Related Knowledge in a Group of Girls Aged 10–12 Years from Ballet School and Artistic Gymnastics Classes

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. General Information

2.2. Study Participants

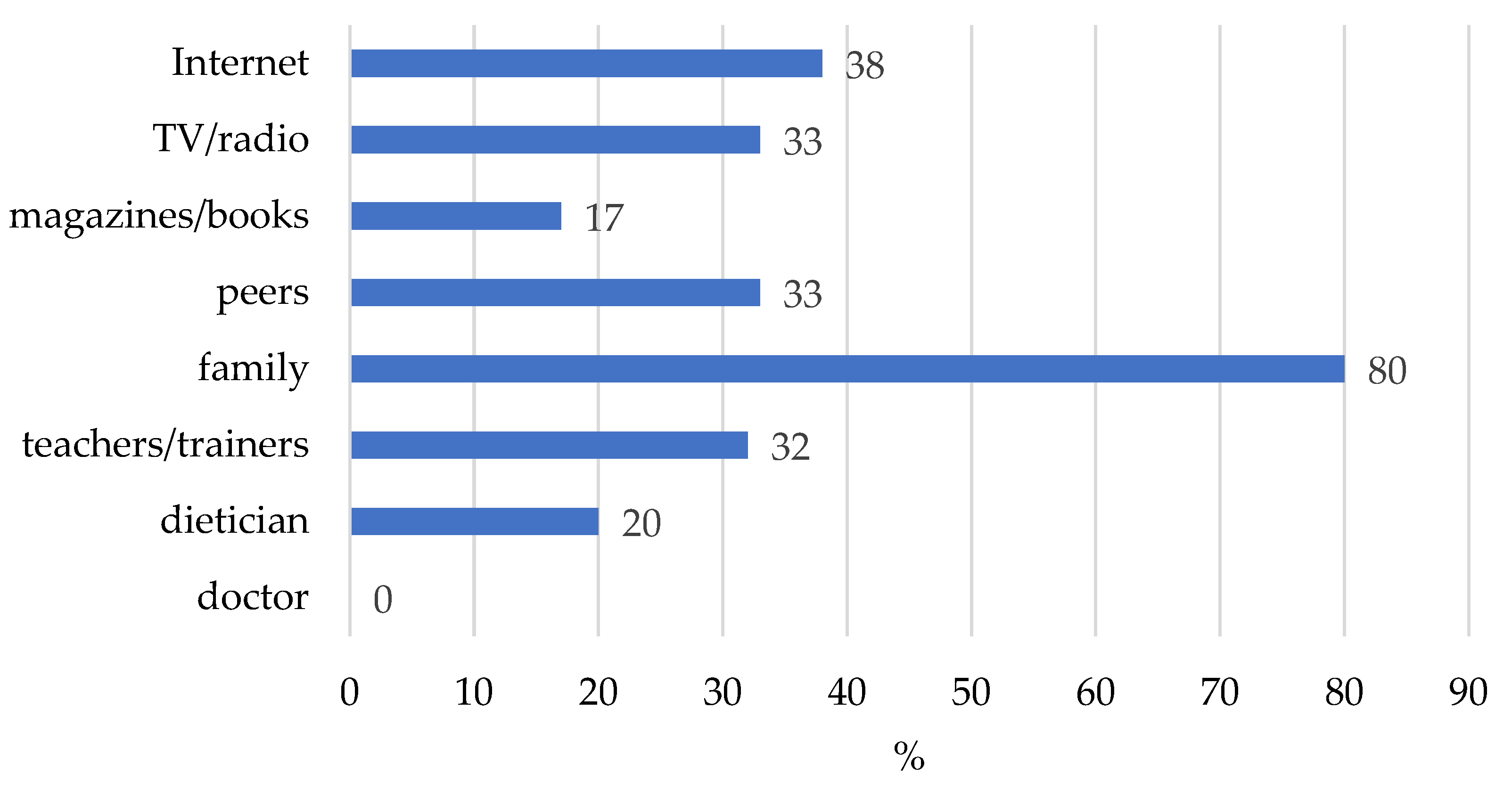

2.3. Evaluation of the Sources of Nutritional Knowledge

2.4. Assessment of Nutritional Knowledge in the Nutritional Education Program

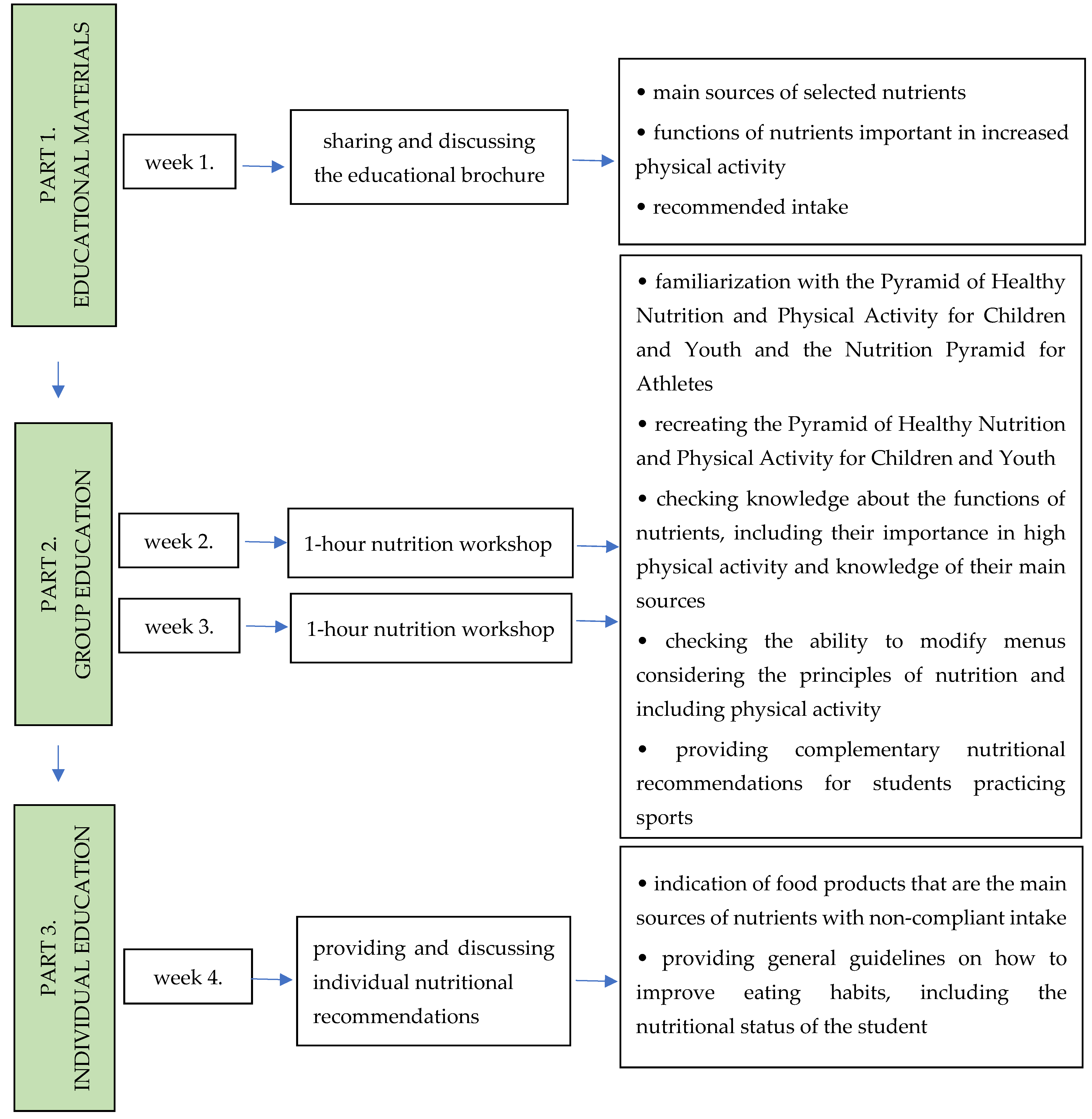

2.4.1. Nutritional Education Program

Educational Materials (Brochure)

Group Education (Nutritional Workshops)

Individual Education (Individual Dietary Recommendations)

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Sources of Nutritional Knowledge

4.2. Forms of Nutritional Education

4.3. Reference Materials and Important Topics of Nutritional Education in the Group of Ballet and Artistic Gymnastics Students

4.4. Results of Implementing Nutritional Programs

4.5. Strengths and Limitations of the Study

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jarosz, M. (Ed.) Nutrition Recommendations for the Polish Population; Institute of Food and Nutrition: Warsaw, Poland, 2017; Available online: https://zywnosc.com.pl/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/normy-zywienia-dla-populacji-polski-2017-1.pdf (accessed on 18 March 2025). (In Polish)

- Smith, J.W.; Holmes, M.E.; McAllister, M.J. Nutritional Considerations for Performance in Young Athletes. J. Sports Med. 2015, 2015, 734649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saribay, A.K.; Kirbaş, Ş. Determination of Nutrition Knowledge of Adolescents Engaged in Sports. Univers. J. Educ. Res. 2019, 7, 40–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ameryk, M.; Świątkowski, M.; Sikorski, P.; Augustyniak, A.; Szamocka, M. Impact of parents’ nutritional knowledge on the nutrition and frequency of consumption of selected products in children and adolescents practicing football in a football club in Bydgoszcz, Poland. J. Educ. Health Sport 2016, 6, 456–472. [Google Scholar]

- Dion, S.; Walker, G.; Lambert, K.; Stefoska-Needham, A.; Craddock, J.C. The Diet Quality of Athletes as Measured by Diet Quality Indices: A Scoping Review. Nutrients 2024, 17, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noll, M.; Rodrigues, A.P.S.; Silveira, E.A. The health-related determinants of eating pattern of high school athletes in Goiás, Brazil. Arch. Public Health 2020, 78, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bielec, G.; Goździejewska, A. Nutritional habits of 11–12-year-old swimmers against non-athlete peers—A pilot study. Pediatr. Endocrinol. Diabetes Metab. 2018, 24, 72–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gacek, M.; Frączek, B. Dietary behaviours and body image perception in youth female ballet dancers. Pol. J. Sports Med. 2010, 26, 134–143. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Leonkiewicz, M.; Wawrzyniak, A. The relationship between rigorous perception of one’s own body and self, unhealthy eating behavior and a high risk of anorexic readiness: A predictor of eating disorders in the group of female ballet dancers and artistic gymnasts at the beginning of their career. J. Eat. Disord. 2022, 10, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bird, S.P.; Rushton, B.D. Nutritional knowledge of youth academy athletes. BMC Nutr. 2020, 6, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaletel, P. Knowledge and Use of Nutritional Supplements in Different Dance Disciplines. Facta Univ. Series Phys. Educ. Sport 2020, 17, 619–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cupisti, A.; D’alessandro, C.; Castrogiovanni, S.; Barale, A.; Morelli, E. Nutrition Knowledge and Dietary Composition in Italian Adolescent Female Athletes and Non-athletes. Int. J. Sport Nutr. Exerc. Metab. 2002, 12, 207–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noronha, D.C.; Santos, M.I.A.F.; Santos, A.A.; Corrente, L.G.A.; Fernandes, R.K.N.; Barreto, A.C.A.; Santos, R.G.J.; Santos, R.S.; Gomes, L.P.S.; Nascimento, M.V.S. Nutrition Knowledge is Correlated with a Better Dietary Intake in Adolescent Soccer Players: A Cross-Sectional Study. J. Nutr. Metab. 2020, 2020, 3519781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Debnath, M.; Chatterjee, S.; Bandyopadhyay, A.; Datta, G.; Dey, S.K. Prediction of Athletic Performance through Nutrition Knowledge and Practice: A Cross-Sectional Study among Young Team Athletes. Sport Mont 2019, 17, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vriendt, T.; Matthys, C.; Verbeke, W.; Pynaert, I.; De Henauw, S. Determinants of nutrition knowledge in young and middle-aged Belgian women and the association with their dietary behaviour. Appetite 2009, 52, 788–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patton-Lopez, M.M.; Manore, M.M.; Branscum, A.; Meng, Y.; Wong, S.S. Changes in Sport Nutrition Knowledge, Atti-tudes/Beliefs and Behaviors Following a Two-Year Sport Nutrition Education and Life-Skills Intervention among High School Soccer Players. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nascimento, M.; Silva, D.; Ribeiro, S.; Nunes, M.; Almeida, M.; Mendes-Netto, R. Effect of a Nutritional Intervention in Athlete’s Body Composition, Eating Behaviour and Nutritional Knowledge: A Comparison between Adults and Adolescents. Nutrients 2016, 8, 535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilo, A.; Lozano, L.; Tauler, P.; Nafría, M.; Colom, M.; Martínez, S. Nutritional Status and Implementation of a Nutritional Education Program in Young Female Artistic Gymnasts. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Łagowska, K.; Kapczuk, K.; Friebe, Z.; Bajerska, J. Effects of dietary intervention in young female athletes with menstrual disorders. J. Int. Soc. Sports Nutr. 2014, 11, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jürgensen, L.P.; Daniel, N.V.S.; Padovani, R.D.C.; Juzwiak, C.R. Impact of a nutrition education program on gymnasts’ perceptions and eating practices. J. Phys. Educ. 2020, 26, e10200206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosmidou, E.; Proios, M.; Giannitsopoulou, E.; Siatras, T.; Doganis, G.; Proios, M.; Douda, H.; Fachantidou-Tsiligiroglou, A. Evaluation of an Intervention Program on Body Esteem, Eating Attitudes and Pressure to Be Thin in Rhythmic Gymnastics Athletes. Sci. Gymnast. J. 2015, 7, 23–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visiedo, A.; Frideres, J.E.; Palao, J.M. Effect of Educational Training on Nutrition and Weight Management in Elite Spanish Gymnasts. Central Eur. J. Sport Sci. Med. 2021, 33, 53–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gawęcki, J. (Ed.) Human Nutrition. Basics of the Science of Nutrition; PWN Publishing: Warsaw, Poland, 2012. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Bonci, L. Sports Nutrition for Young Athletes. Pediatr. Ann. 2010, 39, 300–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Food Pyramid for Athletes. 2009. Available online: https://www.ssns.ch/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/Lebensmittelpyramide_Sport_E1.3.pdf (accessed on 18 March 2025).

- Kunachowicz, H.; Nadolna, I.; Przygoda, B.; Iwanow, K. Tables of Food Composition and Nutritional Value, 1st ed.; PZWL Publishing: Warsaw, Poland, 2005. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Kunachowicz, H.; Nadolna, I.; Przygoda, B.; Iwanow, K. Tables of Food Composition and Nutritional Value, 2nd ed.; PZWL Publishing: Warsaw, Poland, 2017. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Pyramid of Healthy Nutrition and Lifestyle for Children and Youth (4–18 Years); Institute of Food and Nutrition: Warsaw, Poland, 2019. Available online: https://ncez.pzh.gov.pl/dzieci-i-mlodziez/piramida-zdrowego-zywienia-i-stylu-zycia-dzieci-i-mlodziezy-2/ (accessed on 18 March 2025). (In Polish)

- Franciscato, S.J.; Janson, G.; Machado, R.; Lauris, J.R.P.; de Andrade, S.M.J.; Fisberg, M. Impact of the nutrition education Program Nutriamigos® on levels of awareness on healthy eating habits in school-aged children. J. Hum. Growth Dev. 2019, 29, 390–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, M.A.; Howatson, G.; Quin, E.; Redding, E.; Stevenson, E.J. Energy intake and energy expenditure of pre-professional female contemporary dancers. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0171998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purcell, L.K.; Canadian Paediatric Society, Paediatric Sports and Exercise Medicine Section. Sport nutrition for young athletes. Paediatr. Child Health 2013, 18, 200–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-McGehee, T.M.; Pritchett, K.L.; Zippel, D.; Minton, D.M.; Cellamare, A.; Sibilia, M. Sports Nutrition Knowledge Among Collegiate Athletes, Coaches, Athletic Trainers, and Strength and Conditioning Specialists. J. Athl. Train. 2012, 47, 205–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalcarz, W.; Radzimirska-Graczyk, M. Attitude to Nutritional Knowledge in Children and Young People Practicing Fencing. In PHYSIOLOGICAL Conditions of Dietary Management; SGGW-WULS Publishing: Warsaw, Poland, 2004; pp. 466–471. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Boidin, A.; Tam, R.; Mitchell, L.; Cox, G.R.; O’connor, H. The effectiveness of nutrition education programmes on improving dietary intake in athletes: A systematic review. Br. J. Nutr. 2020, 125, 1359–1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogunsile, S.E.; Ogundele, B.O. Effect of game-enhanced nutrition education on knowledge, attitude and practice of healthy eating among adolescents in Ibadan, Nigeria. Int. J. Health Promot. Educ. 2016, 54, 207–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostanjevec, S.; Jerman, J.; Koch, V. The Effects of Nutrition Education on 6th graders Knowledge of Nutrition in Nine-year Primary Schools in Slovenia. Eurasia J. Math. Sci. Technol. Educ. 2011, 7, 243–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudley, D.A.; Cotton, W.G.; Peralta, L.R. Teaching approaches and strategies that promote healthy eating in primary school children: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2015, 12, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, B.; Xu, R.; Watt, T. The Impact of Colors on Learning. Adult Education Research Conference; University of Victoria: Victoria, BC, Canada, 2018. Available online: https://newprairiepress.org/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=4001&context=aerc (accessed on 18 March 2025).

- Hammar Chiriac, E. Group work as an incentive for learning—Students’ experiences of group work. Front. Psychol. 2014, 5, 558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gajewska, D.; Kucharska, A.; Kozak, M.; Wunderlich, S.; Niegowska, J. Effectiveness of Individual Nutrition Education Compared to Group Education, in Improving Anthropometric and Biochemical Indices among Hypertensive Adults with Excessive Body Weight: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abood, D.A.; Black, D.R.; Birnbaum, R.D. Nutrition Education Intervention for College Female Athletes. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2004, 36, 135–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doyle-Lucas, A.F.; Davy, B.M. Development and evaluation of an educational intervention program for pre-professional adolescent ballet dancers: Nutrition for optimal performance. J. Danc. Med. Sci. 2011, 15, 65–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Gross, M.; Gómez-Lorente, J.J.; Valtueña, J.; Ortiz, J.C.; Meléndez, A. The “healthy lifestyle guide pyramid” for children and adolescents. Nutr. Hosp. 2008, 23, 159–168. [Google Scholar]

- Hamulka, J.; Wadolowska, L.; Hoffmann, M.; Kowalkowska, J.; Gutkowska, K. Effect of an Education Program on Nutrition Knowledge, Attitudes toward Nutrition, Diet Quality, Lifestyle, and Body Composition in Polish Teenagers. The ABC of Healthy Eating Project: Design, Protocol, and Methodology. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossiou, D.; Papadopoulou, S.K.; Pagkalos, I.; Kokkinopoulou, A.; Petridis, D.; Hassapidou, M. Energy expenditure and nutrition status of ballet, jazz and contemporary dance students. Prog. Health Sci. 2017, 7, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Figurska-Ciura, D.; Bartnik, J.; Bronkowska, M.; Biernat, J. Qualitative and quantitative assessment of the impact of nutritional education on the intake of selected nutrients and evaluation of nutritional knowledge of young football players. Probl. Hig. Epidemiol. 2014, 95, 471–476. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Eskici, G.; Ersoy, G. An evaluation of wheelchair basketball players’ nutritional status and nutritional knowledge levels. J. Sports Med. Phys. Fit. 2016, 56, 259–268. [Google Scholar]

- Rusińska, A.; Płudowski, P.; Walczak, M.; Borszewska-Kornacka, M.K.; Bossowski, A.; Chlebna-Sokół, D.; Czech-Kowalska, J.; Dobrzańska, A.; Franek, E.; Helwich, E.; et al. Vitamin D Supplementation Guidelines for General Population and Groups at Risk of Vitamin D Deficiency in Poland—Recommendations of the Polish Society of Pediatric Endocrinology and Diabetes and the Expert Panel With Participation of National Specialist Consultants and Representatives of Scientific Societies—2018 Update. Front. Endocrinol. 2018, 9, 246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pludowski, P.; Grant, W.B.; Konstantynowicz, J.; Holick, M.F. Editorial: Classic and Pleiotropic Actions of Vitamin D. Front. Endocrinol. 2019, 10, 341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christakos, S.; Dhawan, P.; Verstuyf, A.; Verlinden, L.; Carmeliet, G. Vitamin D: Metabolism, Molecular Mechanism of Action, and Pleiotropic Effects. Physiol. Rev. 2016, 96, 365–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chryssanthopoulos, C.; Dallas, G.; Arnaoutis, G.; Ragkousi, E.C.; Kapodistria, G.; Lambropoulos, I.; Papassotiriou, I.; Philippou, A.; Maridaki, M.; Theos, A. Young Artistic Gymnasts Drink Ad Libitum Only Half of Their Fluid Lost during Training, but More Fluid Intake Does Not Influence Performance. Nutrients 2023, 15, 2667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Statements in Sections (S) | Correct Answer | Education | p (1) | OR (95% Cl) (2) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % of Students with the Correct Answer (n = 60) | |||||

| Before | After | ||||

| Knowledge of the principles of the Pyramid of Healthy Nutrition and Physical Activity for Children and Youth | |||||

| S1: Cereal products (bread, pasta, rice, groats) should be the main sources of energy in each meal | Yes | 72 | 73 | 0.317 | 1.087 (0.484–2.444) |

| S2: Fruit should be eaten every other day | No | 65 | 73 | 0.025 ** | 1.481 (0.673–3.257) |

| S3: Milk and dairy products (yogurt, kefir, cheese) should be consumed several times a day | Yes | 52 | 58 | 0.046 ** | 1.309 (0.632–2.713) |

| S4: Vegetable fats should be present in the diet in lower amounts than animal fats | No | 33 | 40 | 0.103 | 1.333 (0.628–2.830) |

| Knowledge of the main sources of selected nutrients and their role in the human body | |||||

| S5: Vegetables and fruits are the main sources of iron in the diet | No | 25 | 42 | 0.002 ** | 2.143 ** (0.976–4.703) |

| S6: Nuts are a source of fats that are beneficial for health | Yes | 52 | 63 | 0.008 ** | 1.616 ** (0.773–3.377) |

| S7: (Fatty) Fish is the main source of vitamin D in the diet | Yes | 48 | 60 | 0.008 ** | 1.603 (0.772–3.330) |

| S8: 100 g of meat provides less protein than 100 g of potatoes | No | 63 | 67 | 0.158 | 1.158 (0.542–2.473) |

| Knowledge of the principles of nutrition for students practicing sports/training | |||||

| S9: The main meal (e.g., lunch) should be eaten just before exercise | No | 87 | 88 | 0.317 | 1.160 (0.389–3.483) |

| S10: Fat-and-carbohydrate snacks (e.g., a chocolate bar) are good snacks during training (dance classes) | No | 73 | 77 | 0.157 | 1.195 (0.518–2.758) |

| S11: After intensive training/exercise, first of all, water losses should be replaced | Yes | 90 | 95 | 0.083 * | 2.111 (0.496–8.993) |

| S12: Playing sports (ballet) increases the need for nutrients | Yes | 87 | 90 | 0.157 | 1.385 (0.444–4.314) |

| Nutrition-related knowledge (% of students) | |||||

| lower (≤6 points) | 22 | 13 | 0.025 ** | ||

| medium (7–9 points) | 67 | 60 | 0.285 | ||

| higher (10–12 points) | 12 | 25 | 0.005 ** | ||

| Assessment of Nutrition-Related Knowledge | Education Total Points (n = 60) | p (1) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Before | After | ||

| S: S1–S4 (max 4 points) | 2.2 ± 1.1 | 2.5 ± 1.0 | 0.005 * |

| Wilcoxon effect size = 0.36 | |||

| S: S5–S8 (max 4 points) | 1.9 ± 1.1 | 2.3 ± 1.1 | <0.001 * |

| Wilcoxon effect size = 0.50 | |||

| S: S9–S12 (max 4 points) | 3.4 ± 0.8 | 3.5 ± 0.7 | 0.027 * |

| Wilcoxon effect size = 0.28 | |||

| S: S1–S12 (max 12 points) | 7.5 ± 1.8 | 8.3 ± 1.8 | <0.0001 * |

| Wilcoxon effect size = 0.61 | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Leonkiewicz, M.; Wawrzyniak, A. Evaluation of the Nutritional Education Program in Increasing Nutrition-Related Knowledge in a Group of Girls Aged 10–12 Years from Ballet School and Artistic Gymnastics Classes. Nutrients 2025, 17, 1468. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17091468

Leonkiewicz M, Wawrzyniak A. Evaluation of the Nutritional Education Program in Increasing Nutrition-Related Knowledge in a Group of Girls Aged 10–12 Years from Ballet School and Artistic Gymnastics Classes. Nutrients. 2025; 17(9):1468. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17091468

Chicago/Turabian StyleLeonkiewicz, Magdalena, and Agata Wawrzyniak. 2025. "Evaluation of the Nutritional Education Program in Increasing Nutrition-Related Knowledge in a Group of Girls Aged 10–12 Years from Ballet School and Artistic Gymnastics Classes" Nutrients 17, no. 9: 1468. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17091468

APA StyleLeonkiewicz, M., & Wawrzyniak, A. (2025). Evaluation of the Nutritional Education Program in Increasing Nutrition-Related Knowledge in a Group of Girls Aged 10–12 Years from Ballet School and Artistic Gymnastics Classes. Nutrients, 17(9), 1468. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17091468