An Assessment of Daily Energy Expenditure of Navy Ship Crews and Officers Serving in the Polish Maritime Border Guard as an Indicator of Work Severity and Nutritional Security

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Measurement of Height and Weight

2.3. Measurement of Energy Expenditure

2.4. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of the Study Groups

3.2. Daily Energy Expenditure of Selected Navy Ships Crews During Training at Sea

3.3. Daily Energy Expenditure of Selected Navy Ship Crews During Stay in a Port

3.4. Energy Expenditure of Border Guard Officers Related to the Service and Implementation of Training Tasks

3.5. Energy Value and Content of Protein, Fats, and Carbohydrates in Rations Planned and Given for Consumption to Sailors of Selected Polish Navy Ships

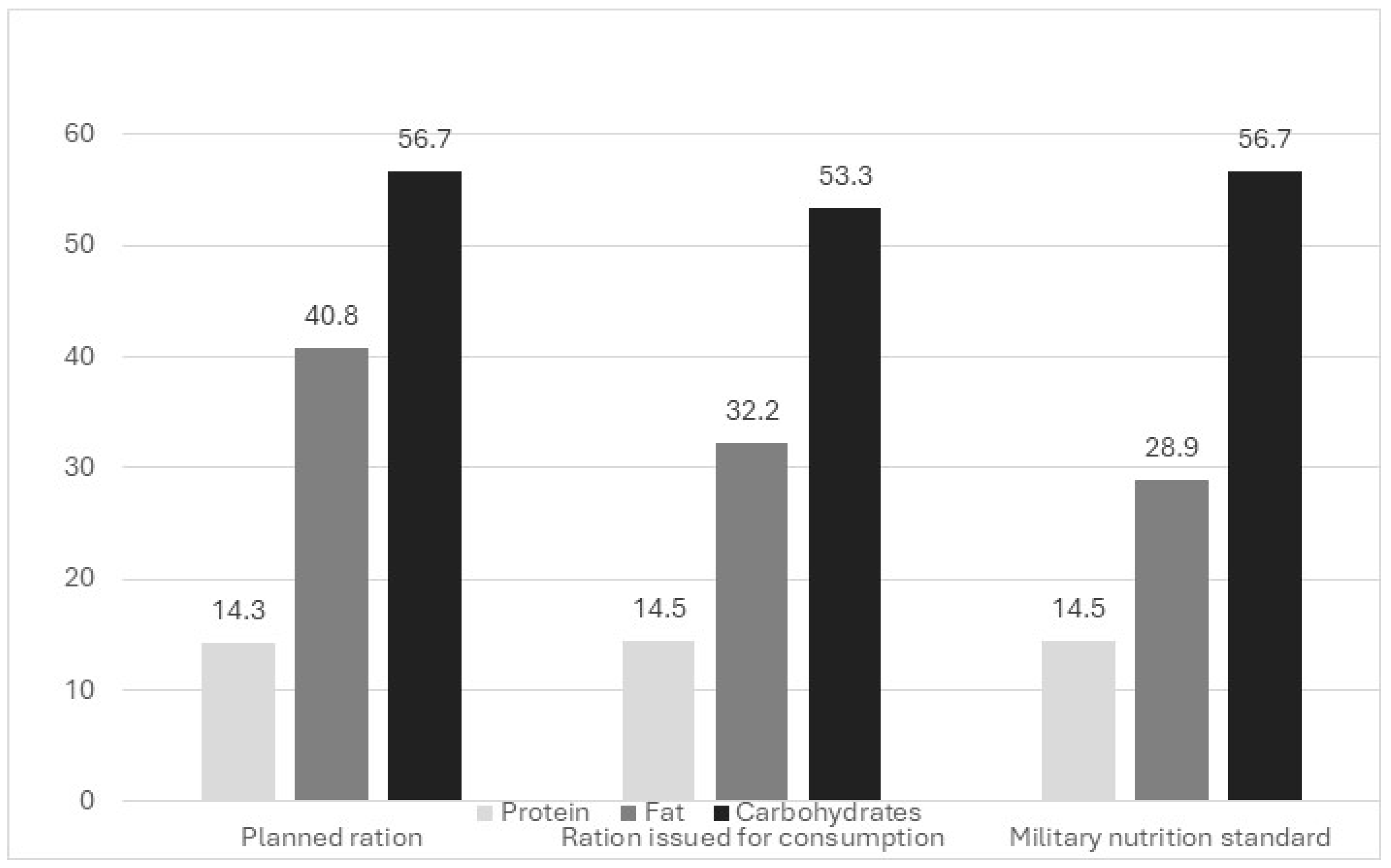

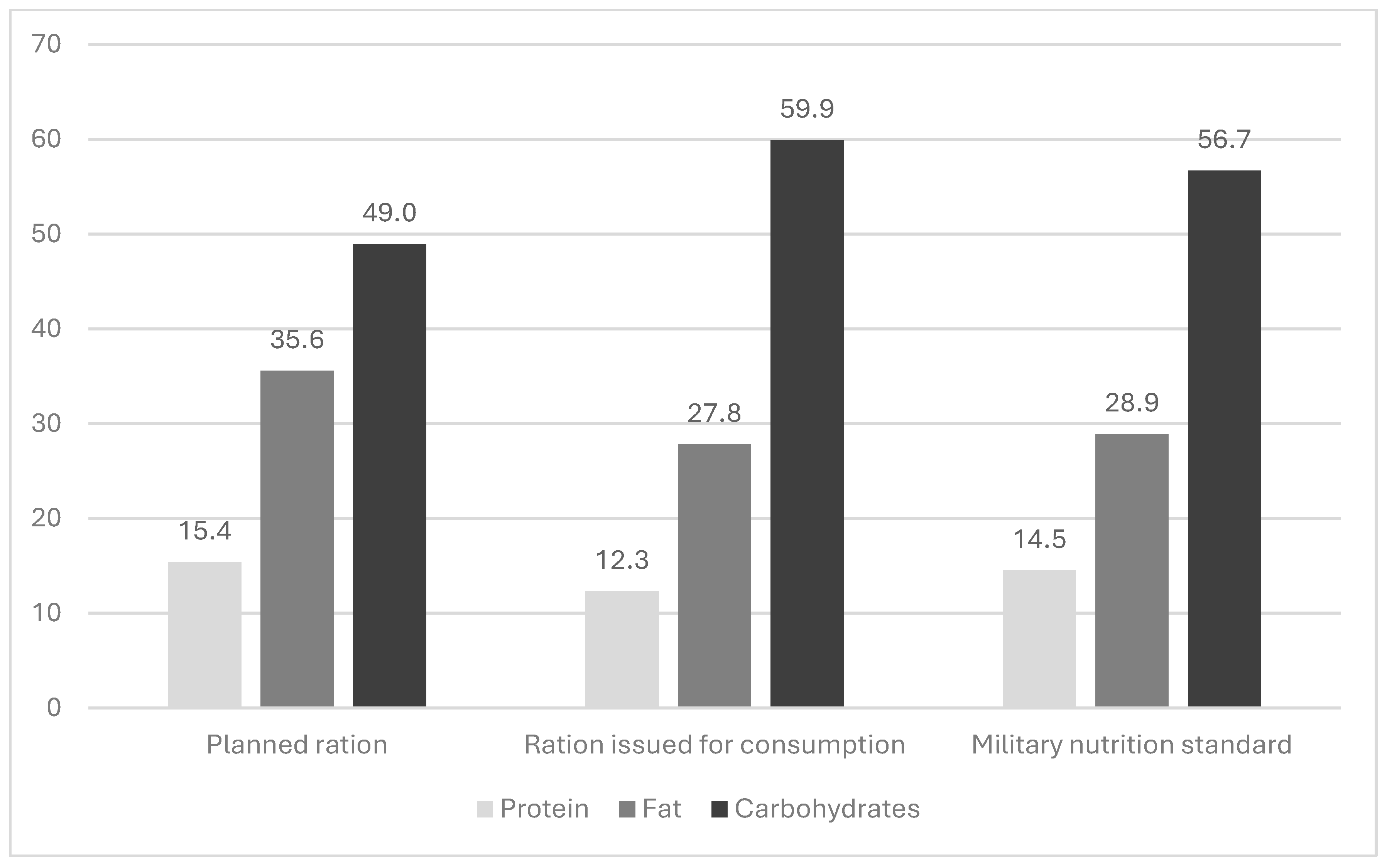

3.6. Percentage of Energy from Protein, Fats, and Carbohydrates in Food Rations Planned and Given for Consumption to the Sailors of Selected Polish Navy Ships

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

- The energy load of Polish Navy ships crews and the Border Guard Maritime Unit officers related to the execution of official and training tasks varies and depends on the type of ship, the function performed on the ship, and the conditions for the performance of service and training tasks, and the severity of the work performed by an individual sailor is classified in categories ranging from light to very heavy;

- The prevalence of overweight and obesity among ship crews and the Border Guard Maritime Unit officers requires the development and implementation of a dedicated dietary standard for these services, and it needs to be balanced in terms of energy and all nutrients;

- There is a need to spread nutrition education among sailors, as well as personnel responsible for planning and implementing nutrition on ships, and among Border Guard officers in terms of the knowledge of a rational, health-promoting model of nutrition and, consequently, in making the right dietary choices;

- Ensuring the nutritional safety of the Polish Navy crews and the Border Guard Maritime Unit officers requires the development and implementation of a nutrition model considering the nature and specificity of their service.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Food Safety, Quality and Consumer Protection. Assuring Food Safety and Quality: Guidelines for Strengthening National Food Control Systems; FAO/WHO: Rome, Italy, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Food and Nutrition Security. Available online: https://www.nifa.usda.gov/topics/food-nutrition-security (accessed on 28 November 2024).

- Pérez-Escamilla, R. Food and nutrition security definitions, constructs, frameworks, measurements, and applications: Global lessons. Front. Public Health 2024, 12, 1340149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Available online: www.gov.pl/web/obrona-narodowa/marynarka-wojenna (accessed on 12 November 2024).

- Surina, I. The role of the Border Guard in ensuring national security. Secur. Dimens. 2020, 3, 134–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klos, A.; Bertrandt, J.; Kurkiewicz, Z. The assessment of nutritional status of the selected Navy warship crew. Rocz. Panstw. Zakl. Hig. 2007, 58, 259–265. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Bertrandt, J.; Kłos, A.; Janda, E.; Frańczuk, H. Assessment of nutritional status of sailors serving on Polish Navy ships. Lek Wojsk 1988, 6, 692–696. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Available online: https://support.polar.com/e_manuals/RC3_GPS/Polar_RC3_GPS_user_manual_English/manual.pdf (accessed on 10 November 2024).

- Kloss, E.B.; Givens, A.; Palombo, R.; Bernards, J.; Niederberger, B.; Bennett, B.W.; Kelly, K.R. Validation of Polar Grit X Pro for Estimating Energy Expenditure during Military Field Training: A Pilot Study. J. Sports Sci. Med. 2023, 22, 658–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PN-EN ISO 8996:2005; Ergonomics of the Thermal Environment—Determination of Metabolic Rate. Polish Committee for Standardization: Warsaw, Poland, 2013.

- Wang, R.; Blackburn, G.; Desai, M.; Phelan, D.; Gillinov, L.; Houghtaling, P.; Gillinov, M. Accuracy of Wrist-Worn Heart Rate Monitors. JAMA Cardiol. 2017, 2, 104–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miernik Wydatku Energetycznego MWE-1. Available online: http://www.cbe.com.pl/index.php/ida/3/?idp=55 (accessed on 9 January 2025).

- Rdzanek, J.; Jędrasiewicz, T.; Kłos, A. Tabele Wydatków Energetycznych Żołnierzy Polskich Różnych Rodzajów Wojsk i Służb; Military Institute of Hygiene and Epidemiology: Warszawa, Poland, 1982. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Lehmann, G. Praktyczna Fizjologia Pracy; PZWL: Warszawa, Poland, 1966. [Google Scholar]

- Christensen, C.G.; Frey, H.M.; Foenstein, E.A. A critical evaluation of energy expenditure estimates based on individual O2 consumption/heart rate curves and average daily heart rate. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1983, 37, 468–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szczegółowe Wymiary Rzeczowe Norm Wyżywienia Żołnierzy w Czasie Pokoju; Generalny Zarząd Logistyki P-4: Warszawa, Poland, 2006. (In Polish)

- Cheney, S.A.; Xenakis, S.N. Obesity’s Increasing Threat to Military Readiness: The Challenge to U.S. National Security. 1 November 2022. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/resrep46869 (accessed on 12 November 2024).

- Anyżewska, A.; Lakomy, R.; Lepionka, T.; Maculewicz, E.; Szarska, E.; Tomczak, A.; Bolczyk, I.; Bertrandt, J. Association between Diet, Physical Activity and Nutritional Status of Male Border Guard Officers. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 5305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miggantz, E.L.; Materna, K.; Herbert, M.S.; Golshan, S.; Hernandez, J.; Peters, J.; Delaney, E.; Webb-Murphy, J.; Wisbach, G.; Afari, N. Characteristics of active-duty ser-vice members referred to the navy’s weight-management program. Mil. Med. 2023, 188, e174–e181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanderson, P.W.; Clemes, S.A.; Biddle, S.J. The correlation and treatment of obesity in military populations: A systematic review. Obes. Facts 2011, 4, 229–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quertier, D.; Goudard, Y.; Goin, G.; Régis-Marigny, L.; Sockeel, P.; Dutour, A.; Pauleau, G.; De La Villéon, B. Overweight and obesity in the French army. Mil. Med. 2022, 187, e99–e105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salimi, Y.; Taghdir, M.; Sepandi, M.; Zarchi, A.-A.K. The prevalence of overweight and obesity among Iranian military personnel: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bebnowicz, A.; Nowosad, A. Assessment of nutritional status of selected military personnel. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2020, 79, E259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaździńska, A.; Jagielski, P.; Turczyńska, M.; Dziuda, Ł.; Gaździński, S. Assessment of Risk Factors for Development of Overweight and Obesity among Soldiers of Polish Armed Forces Participating in the National Health Program 2016–2020. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 3069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bray, R.M.; Camlin, C.S.; Fairbank, J.A.; Dunteman, G.H.; Wheeless, S.C. The effects of stress on job functioning of military men and women. Armed Forces Soc. 2001, 27, 397–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chukwura, C.L.; Santo, T.J.; Waters, C.N.; Andrews, A. Nutrition is out of our control: Soldiers’ perceptions of their local food environment. Public Health Nutr. 2019, 22, 2766–2776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaździńska, A.; Baran, P.; Turczyńska, M.; Jagielski, P. Evaluation of health behaviors of Polish Army soldiers in relation to demographic factors, body weight and type of armed forces. Int. J. Occup. Med. Environ. Health 2023, 36, 437–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlton, J.R.; Manos, G.H.; Van Slyke, J.A. Anxiety and abnormal eating behaviors associated with cyclical readiness testing in a naval hospital active-duty population. Mil. Med. 2005, 170, 663–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertrandt, J.; Lakomy, R.; Klos, A. Energy expenditure of selected Polish Navy warship crews. Lek. Wojsk. 2011, 1, 36–39. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Tharion, W.J.; Lieberman, H.R.; Montain, S.J.; Young, A.J.; Baker-Fulco, C.J.; DeLany, J.P.; Hoyt, R.W. Energy requirements of military personnel. Appetite 2005, 44, 47–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertrandt, J.; Łakomy, R.; Kłos, A. Wydatek energetyczny załóg wybranych okrętów Marynarki Wojennej RP, Lek. Wojsk 2011, 89, 36–39. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Forbes-Ewan, C.H.; Morrissey, B.L.L.; Gregg, G.C.; Waters, D.R. Food Intake and Energy Expenditure of Sailors at a Large Naval Base; MRL Technical Report MRL-TR-90-11; DSTO Materials Research Laboratory: Maribyrnong. VIC, Australia, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, V.K.; Dutta, A.A.; Shukla, V.; Vats, P.; Singh, S.M. Energy Expenditure and Nutritional Status of Sailors and Submarine Crew of the Indian Navy. Def. Sci. J. 2011, 61, 540–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Rietjens, G.; Most, J.; Joris, P.J.; Helmhout, P.; Plasqui, G. Energy Expenditure and Changes in Body Composition During Submarine Deployment—An Observational Study “DasBoost 2-2017”. Nutrients 2020, 12, 226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gunner, F.; Reece, D.; Hambly, C.; Speakman, J.R.; Fallowfield, I.L. The energy expenditure of Royal Navy submariners. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2018, 77, E154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellani, J.W.; Hoyt, R.W.; Young, A.J.; DeLany, J.P.; Gonzalez, R.R. Core Temperature and Energy Expenditure During the Crucible Exercise at Marine Corps Recruit Depot, Parris Island; Technical Report No. T98-26; United States Army Research Institute of Environmental Medicine: Natick, MA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Bathalon, G.P.; Mcgraw, S.M.; Falco, C.M.; Greorgelis, J.H.; DeLany, J.P.; Young, A. Total energy expenditure during strenuous U.S. Marine Corps recruit training. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2003, 35 (Suppl. S1), S182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tharion, W.J.; Yokota, M.; Buller, M.J.; DeLany, J.P.; Hoyt, R.W. Daily expenditures (TDEEs) using Foot-Contact Pedometer. Med. Sci. Monit. 2004, 10, CR504-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Forbes-Ewan, C.; Morrissey, B.; Waters, D.; Gregg, G. Food Intake and Energy Expenditure of Sailors at a Large Naval Base. Scottsdale Tasmania, Australia: Material Research Laboratory of Defense Science and Technology Organization; Technical Report TR 90-11; MRL: Canberra, Australia, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Fallowfield, J.L.; Delves, S.K.; Shaw, A.M.; Bentley, C.; Lanham-New, S.A.; Busbridge, M.; Darch, S.; Britland, S.; Allsopp, A.J. Surgeon General’s Armed Forces Feeding Project: Operational Feeding Onboard Ship (HMS Daring); Report 2013.028; Institute of Naval Medicine: Alverstoke, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Fallowfield, J.L.; Delves, S.K.; Brown, P.; Dziubak, A.; Bentley, C. Surgeon General’s Armed Forces Feeding Project: Operational Feeding Onboard Ship (HMS Dauntless); Report 2012.009; Institute of Naval Medicine: Alverstoke, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Hyżyk, A.; Krejpcio, Z.; Dyba, S. Evaluation of the method of soldiers’ feeding in selected army units. Probl. Hig. Epidemiol. 2011, 92, 526–529. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Army Regulation 40–25 OPNAVINST 10110.1/MCO 10110.49 AFI 44–141; Nutrition and Menu Standards for Human Performance Optimization. Headquarters Departments of the Army, the Navy, and the Air Force: Washington, DC, USA, 2017.

- Bridger, R.S.; Brasher, K.; Bennett, A. Sustaining a person’s environment fit with a changing workforce. Ergonomics 2012, 56, 565–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, A.M.; Simpson, D.; Davey, T.; Fallowfield, J.L. Surgeon General’s Armed Forces Feeding Project: The Royal Navy: Obesity, Eating Behaviours and Factors Influencing Food Choices; Report 2013.022; Institute of Naval Medicine: Alverstoke, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Sundin, J.; Fear, N.T.; Wessely, S.; Rona, R.J. Obesity in the UK Armed Forces: Risk Factors. Mil. Med. 2011, 176, 507–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bridger, R.S.; Bennett, A.; Brasher, K. Lifestyle, Body Mass Index and Self-Reported Health in the Royal Navy 2007–2011; Report No 2011036; Institute of Naval Medicine (INM): Alverstoke, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Shaw, A.M.; Simpson, D.; Davey, T.; Fallowfield, J.L. Body mass index and waist circumference: Implications for classifying the prevalence of overweight and obesity in the Royal Navy. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2013, 72, E274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasier, H.G.; Hughes, L.; Young, C.R.; Richardson, A.M. Comparison of Body Composition Assessed by Dual-Energy X-Ray Absorptiometry and BMI in Current and Former U.S. Navy Service Members. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0132157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gregg, M.A.; Jankosky, C.J. Physical readiness and obesity among male U.S. Navy personnel with limited exercise availability while at sea. Mil. Med. 2012, 177, 1302–1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lennon, R.P.; Oberhofer, A.P.; McQuade, J. Body Composition Assessment Failure Rates and Obesity in the United States Navy. Mil. Med. 2015, 180, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Macera, C.A.; Aralis, H.; MacGregor, A.; Rauh, M.J.; Heltemes, K.; Han, P.; Galarneau, M.R. Weight changes among male Navy personnel deployed to Iraq or Kuwait in 2005–2008. Mil. Med. 2011, 176, 500–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nash, J. Obesity Is It a Factor Within the Naval Service. Ireland, Cork: Unpublished Final Year Dissertation; National Maritime College of Ireland: Cork, Ireland, 2009. [Google Scholar]

| Degree of Severity of Work | Daily Energy Expenditure—24 h | Energy Expenditure Per Work Shift—8 h | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kcal | MJ | Kcal | MJ | |

| Light | 2300–2800 | 9.6–11.7 | ≤500 | ≤2.1 |

| Moderate | 2800–3300 | 11.7–13.8 | 500–1000 | 2.1–4.2 |

| Moderate hard | 3300–3800 | 13.8–15.9 | 1000–1500 | 4.2–6.3 |

| Hard | 3800–4300 | 15.9–18,0 | 1500–2000 | 6.3–8.4 |

| Very hard | 4300–4800 | 18.0–20.1 | 2000–2800 | 8.4–11.7 |

| Extremely hard | ≥4800 | ≥20.1 | ≥4800 | ≥11.7 |

| Degree of Work Severity | The Amount of Energy Load |

|---|---|

| Light | >2.5 kcal/min |

| Moderate | >5.0 kcal/min |

| Hard | >7.5 kcal/min |

| Very hard | >10.0 kcal/min |

| Extremely hard | >12.5 kcal/min |

| Ship | Misle Frigate No-74 | Training Sailing Ship No-30 | Maritime Border Guard Unit No-89 | Kashubian Border Guard Division No-21 | Average |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age [years] | 29.8 ± 4.2 | 21.6 ± 2.8 * | 37.6 ± 3.6 * | 28.4 ± 2.1 | 29.3 ± 6.5 |

| Body weight [kg] | 80.4 ± 4.1 | 79.5 ± 13.8 | 84.1 ± 9.8 * | 82.1 ± 7.8 | 81.5 ± 2.0 |

| Height [cm] | 177.9 ± 3.5 | 179.3 ± 6.7 | 179.7 ± 6.3 | 177.7 ± 6.3 | 178.6 ± 0.9 |

| BMI | 25.4 ± 1.6 | 24.8 ± 1.4 | 26.3 ± 1.2 * | 26.2 ± 1.4 * | 25.7 ± 1.4 |

| Time | Activity | Duration of the Activity [min] | Energy Expenditure [kcal/min/kg b. m.] | Energy Expenditure of the Activity [kcal] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 315–350 | Night patrol | 35 | 0.0433 | 121.8 ± 7.2 |

| 350–400 | Night watch briefing | 10 | 0.0310 | 24.9 ± 2.2 |

| 400–600 | Change of sea watch | 120 | 0.0310 | 299.1 ± 14.1 |

| 600–610 | Wake up and preparation for morning exercises | 10 | 0.0475 | 38.2 ± 2.6 |

| 610–630 | Morning exercises | 20 | 0.0706 | 113.5 ± 3.3 |

| 630–650 | Morning wash up | 20 | 0.0595 | 95.7 ± 2.6 |

| 650–720 | Cleaning the ship | 30 | 0.0425 | 102.5± 3.1 |

| 720–750 | Breakfast | 30 | 0.0412 | 99.4 ± 1.1 |

| 750–800 | New watch briefing | 10 | 0.0310 | 24.9 ± 3.3 |

| 800–1130 | Training and ship service | 210 | 0.0381 | 643.3 ± 22.2 |

| 1130–1200 | Preparation for lunch | 30 | 0.0475 | 114.6 ± 4.6 |

| 1200–1230 | Lunch | 30 | 0.0412 | 99.4 ± 8.1 |

| 1230–1400 | Break after lunch | 90 | 0.0202 | 146.2 ± 4.1 |

| 1400–1600 | Training and ship service | 120 | 0.0381 | 367.6 ± 21.2 |

| 1600–1620 | 1st dinner | 20 | 0.0412 | 66.2 ± 13.6 |

| 1620–1630 | Briefing and change of watch | 10 | 0.0310 | 24.9 ± 2.2 |

| 1630–1750 | Time at the ship commander’s disposal | 80 | 0.0214 | 137.6 ± 11.6 |

| 1750–1815 | Briefing and change of watch | 25 | 0.0310 | 62.3 ± 3.6 |

| 1815–1930 | Auxiliary work in the ship’s kitchen | 75 | 0.0614 | 370.2 ± 17.5 |

| 1930–2000 | Free time | 30 | 0.0360 | 86.8 ± 5.3 |

| 2000–2020 | 2nd dinner | 20 | 0.0412 | 66.2 ± 6.6 |

| 2020–2030 | Watch briefing | 10 | 0.0310 | 24.9 ± 3.3 |

| 2030–2045 | Change of sea watch | 15 | 0.0276 | 33.3 ± 2.2 |

| 2045–2130 | Evening patrol | 45 | 0.0433 | 156.6 ± 42.1 |

| 2130–2150 | Evening toilet | 20 | 0.0595 | 95.7 ± 12.3 |

| 2150–2200 | Night watch briefing | 10 | 0.0310 | 24.9 ± 3.2 |

| 2200–2215 | Change of sea watch | 15 | 0.0276 | 33.3 ± 2.2 |

| 2215–315 | Sleep | 300 | 0.0166 | 400.4 ± 22.6 |

| Daily energy expenditure | 1440 | 3874 ± 248 | ||

| Time | Activity | Duration of the Activity [min] | Energy Expenditure [kcal/min/kg b. m.] | Energy Expenditure of the Activity [kcal] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 315–350 | Night patrol | 35 | 0.0433 | 120.5 ± 22.6 |

| 350–400 | Night watch briefing | 10 | 0.0310 | 24.6± 6.6 |

| 400–600 | Change of sea watch | 120 | 0.0310 | 295.7 ± 22.1 |

| 600–610 | Wake up and preparation for morning exercises | 10 | 0.0475 | 37.8 ± 11.3 |

| 610–630 | Morning exercises | 20 | 0.0706 | 112.2 ± 13.7 |

| 630–650 | Morning wash up | 20 | 0.0595 | 94.6 ± 6.4 |

| 650–720 | Cleaning the ship | 30 | 0.0425 | 101.4 ± 13.2 |

| 720–750 | Breakfast | 30 | 0.0412 | 98.3 ± 8.9 |

| 750–800 | New watch briefing | 10 | 0.0310 | 24.6 ± 6.6 |

| 800–1130 | Training and ship service | 210 | 0.0456 | 761.3 ± 33.9 |

| 1130–1200 | Preparation for lunch | 30 | 0.0475 | 114.0 ± 10.6 |

| 1200–1230 | Lunch | 30 | 0.0412 | 98.3 ± 8.1 |

| 1230–1400 | Break after lunch | 90 | 0.0202 | 144.5± 23.5 |

| 1400–1600 | Training and ship service | 120 | 0.0456 | 435.0± 38.2 |

| 1600–1620 | 1st dinner | 20 | 0.0412 | 65.5 ± 13.3 |

| 1620–1630 | Briefing and change of watch | 10 | 0.0310 | 24.6 ± 6.3 |

| 1630–1750 | Time at the ship commander’s disposal | 80 | 0.0214 | 136.1 ± 21.7 |

| 1750–1815 | Briefing and change of watch | 25 | 0.0310 | 61.6 ± 11.6 |

| 1815–1930 | Auxiliary work in the ship’s kitchen | 75 | 0.0614 | 368.4± 56,7 |

| 1930–2000 | Free time | 30 | 0.0360 | 85.8± 13.7 |

| 2000–2020 | 2nd dinner | 20 | 0.0412 | 65.5 ± 17.1 |

| 2020–2030 | Watch briefing | 10 | 0.0310 | 24.6 ± 6.3 |

| 2030–2045 | Change of sea watch | 15 | 0.0276 | 32.9 ± 5.2 |

| 2045–2130 | Evening patrol | 45 | 0.0433 | 154.9 ± 33.3 |

| 2130–2150 | Evening toilet | 20 | 0.0595 | 94.6 ± 17.2 |

| 2150–2200 | Night watch briefing | 10 | 0.0310 | 24.6 ± 6.3 |

| 2200–2215 | Change of sea watch | 15 | 0.0276 | 37.0 ± 6.6 |

| 2215–315 | Sleep | 300 | 0.0166 | 237.5 ± 18.8 |

| Daily energy expenditure | 1440 | 4031 ± 436 | ||

| Time | Activity | Duration of the Activity [min] | Energy Expenditure [kcal/min/kg b. m.] | Energy Expenditure of the Activity [kcal] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 600–610 | Wake up and preparation for morning exercises | 10 | 0.0475 | 38.2 ± 2.6 |

| 610–630 | Morning exercises | 20 | 0.0706 | 113.5 ± 17.6 |

| 630–700 | Morning wash up | 30 | 0.0595 | 143.5 ± 22.8 |

| 700–720 | Breakfast | 20 | 0.0412 | 66.2 ± 12.1 |

| 720–740 | Cleaning the ship | 20 | 0.0624 | 100.3 ± 18.3 |

| 740–750 | New watch briefing | 10 | 0.0310 | 24.9 ± 4.7 |

| 750–800 | Raising the flag | 10 | 0.0310 | 24.9 ± 5.3 |

| 800–835 | Overview and rotated mechanisms | 35 | 0.0433 | 121.8± 38.8 |

| 835–1215 | Activities on the ship | 220 | 0.0433 | 765.9 ± 44.5 |

| 1215–1315 | Lunch break | 60 | 0.0412 | 198.7 ± 23.6 |

| 1315–1500 | Scheduled classes | 105 | 0.0433 | 365.5 ± 36.8 |

| 1500–1520 | Roll call | 20 | 0.0310 | 49.8 ± 8.2 |

| 1520–1600 | Cleaning the ship | 40 | 0.0425 | 136.7 ± 27.9 |

| 1600–1800 | Free time | 120 | 0.0214 | 206.5 ± 33.1 |

| 1800–1830 | Dinner | 30 | 0.0412 | 99.4 ± 11.2 |

| 1830–2100 | Free time | 150 | 0.0214 | 258.1 ± 28.9 |

| 2100–2130 | Cleaning the ship | 30 | 0.0624 | 150.5 ± 9.6 |

| 2130–2200 | Evening toilet | 30 | 0.0595 | 143.5 ± 11.8 |

| 2200–600 | Sleep | 480 | 0.0166 | 640.6 ± 26.9 |

| Daily energy expenditure | 1440 | 3648 ± 332 | ||

| Time | The Name of the Activity | Duration of the Activity [min] | Energy Expenditure [kcal/min/kg b. m.] | Energy Expenditure of the Activity [kcal] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 600–610 | Wake up and preparation for morning exercises | 10 | 0.0475 | 37.8 ± 6.2 |

| 610–630 | Morning exercises | 20 | 0.0706 | 112.2 ± 29.3 |

| 630–700 | Morning wash up | 30 | 0.0595 | 141.9 ± 21.5 |

| 700–720 | Breakfast | 20 | 0.0412 | 65.5 ± 11.6 |

| 720–740 | Cleaning the ship | 20 | 0.0624 | 99.2 ± 18.8 |

| 740–750 | New watch briefing | 10 | 0.0310 | 24.6 ± 5.1 |

| 750–800 | Raising the flag | 10 | 0.0310 | 24.6 ± 5.0 |

| 800–835 | Overview and rotated mechanisms | 35 | 0.1199 | 333.6 ± 42.1 |

| 835–1215 | Activities on the ship | 220 | 0.0456 | 797.5± 53.7 |

| 1215–1315 | Lunch break | 60 | 0.0412 | 196.5± 21.2 |

| 1315–1500 | Scheduled classes | 105 | 0.0456 | 380.6 ± 33.1 |

| 1500–1520 | Roll call | 20 | 0.0310 | 49.3 ± 9.7 |

| 1520–1600 | Cleaning the ship | 40 | 0.0425 | 135.2 ± 21.6 |

| 1600–1800 | Free time | 120 | 0.0214 | 204.2 ± 33.1 |

| 1800–1830 | Dinner | 30 | 0.0341 | 98.3 ± 15.5 |

| 1830–2100 | Free time | 150 | 0.0214 | 255.2 ± 34.3 |

| 2100–2130 | Cleaning the ship | 30 | 0.0624 | 148.8 ± 38.7 |

| 2130–2200 | Evening toilet | 30 | 0.0595 | 141.9 ± 26.8 |

| 2200–600 | Sleep | 480 | 0.0166 | 633.5 ± 33.7 |

| Daily energy expenditure | 1440 | 3380 ± 461 | ||

| n = 89 | Maritime Border Guard Unit | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| x | ± | SD | Median | Min | ÷ | Max | ||

| Energy expenditure | time [h] | 15.6 | ± | 6.1 | 11.7 | 7.2 | ÷ | 23.3 |

| kcal/h | 142 | ± | 50 | 138 | 61 | ÷ | 230 | |

| kcal/min | 2.36 | ± | 0.83 | 2.30 | 1.02 | ÷ | 3.84 | |

| kcal/h/kg b. m. | 2.13 | ± | 0.94 | 1.92 | 0.67 | ÷ | 3.89 | |

| kcal/min/kg b. m. b.m. mc | 0.036 | ± | 0.016 | 0.032 | 0.011 | ÷ | 0.065 | |

| kcal measured | 2100 | ± | 959 | 1661 | 954 | ÷ | 4193 | |

| Pulse | max | 149 | ± | 32 | 140 | 107 | ÷ | 220 |

| min | 53 | ± | 7 | 53 | 42 | ÷ | 68 | |

| average | 82 | ± | 11 | 78 | 69 | ÷ | 102 | |

| Total | Kcal/12 h | 1703 | ± | 599 | 1657 | 735 | ÷ | 2762 |

| n = 21 | Kashubian Border Guard Division | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| x | ± | SD | Median | Min | ÷ | Max | ||

| Energy expenditure | time [h] | 25.3 | ± | 0.2 | 25.3 | 25.2 | ÷ | 25.6 |

| kcal/h | 98 | ± | 39 | 73 | 69 | ÷ | 153 | |

| kcal/min | 1.64 | ± | 0.64 | 1.22 | 1.15 | ÷ | 2.54 | |

| kcal/h/kg mc | 1.35 | ± | 0.66 | 0.94 | 0.84 | ÷ | 2.28 | |

| kcal/min/kg mc | 0.023 | ± | 0.011 | 0.016 | 0.014 | ÷ | 0.038 | |

| kcal measured | 2482 | ± | 960 | 1868 | 1739 | 3838 | ||

| Pulse | max | 146 | ± | 18 | 151 | 122 | ÷ | 166 |

| min | 55 | ± | 9 | 61 | 43 | ÷ | 62 | |

| average | 77 | ± | 6 | 79 | 68 | ÷ | 83 | |

| Total | Kcal/12 h | 1178 | ± | 462 | 876 | 826 | ÷ | 1830 |

| Missile Frigate | School Sailing Ship | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Planned Food Ration | Food Ration Given for Consumption | Planned Food Ration | Food Ration Given for Consumption | |

| Energy value (kcal) | 4430.9 ± 322.6 | 4120.0 ± 300.8 *,● | 4234.7 ± 419.6 | 3520.9 ± 365.0 * |

| Protein content (g) | 158,3 ± 17.4 | 149,3 ± 17.9 | 163.0 ± 14.7 | 108.2 ± 13.9 * |

| Fat content (g) | 201.0 ± 34.6 ● | 147.4 ± 23.5 * | 167.5 ± 28.6 | 108.7 ± 21.3 * |

| Carbohydrates content (g) | 497.2 ± 53.3 ● | 547.5 ± 53.3 *,● | 518.7 ± 64.2 ● | 527.5 ± 54.2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bertrandt, J.; Pawlisiak, M.; Bolczyk, I.; Grudniewski, T.; Lakomy, R.; Tomczak, A.; Bertrandt, K.; Lepionka, T.; Brewinska, D.; Bandura, J.; et al. An Assessment of Daily Energy Expenditure of Navy Ship Crews and Officers Serving in the Polish Maritime Border Guard as an Indicator of Work Severity and Nutritional Security. Nutrients 2025, 17, 953. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17060953

Bertrandt J, Pawlisiak M, Bolczyk I, Grudniewski T, Lakomy R, Tomczak A, Bertrandt K, Lepionka T, Brewinska D, Bandura J, et al. An Assessment of Daily Energy Expenditure of Navy Ship Crews and Officers Serving in the Polish Maritime Border Guard as an Indicator of Work Severity and Nutritional Security. Nutrients. 2025; 17(6):953. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17060953

Chicago/Turabian StyleBertrandt, Jerzy, Mieczysław Pawlisiak, Izabela Bolczyk, Tomasz Grudniewski, Roman Lakomy, Andrzej Tomczak, Karolina Bertrandt, Tomasz Lepionka, Dorota Brewinska, Justyna Bandura, and et al. 2025. "An Assessment of Daily Energy Expenditure of Navy Ship Crews and Officers Serving in the Polish Maritime Border Guard as an Indicator of Work Severity and Nutritional Security" Nutrients 17, no. 6: 953. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17060953

APA StyleBertrandt, J., Pawlisiak, M., Bolczyk, I., Grudniewski, T., Lakomy, R., Tomczak, A., Bertrandt, K., Lepionka, T., Brewinska, D., Bandura, J., & Anyzewska, A. (2025). An Assessment of Daily Energy Expenditure of Navy Ship Crews and Officers Serving in the Polish Maritime Border Guard as an Indicator of Work Severity and Nutritional Security. Nutrients, 17(6), 953. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17060953