Gender, Adverse Changes in Social Engagement and Risk of Unhealthy Eating: A Prospective Cohort Study of the Canadian Longitudinal Study on Aging (2011–2021)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population and Eligible Sample

2.2. Changes in Fruit or Vegetable Intake

2.3. Changes in Social Isolation and Breadth of Social Participation

2.4. Covariables

2.5. Sex and Gender Considerations

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

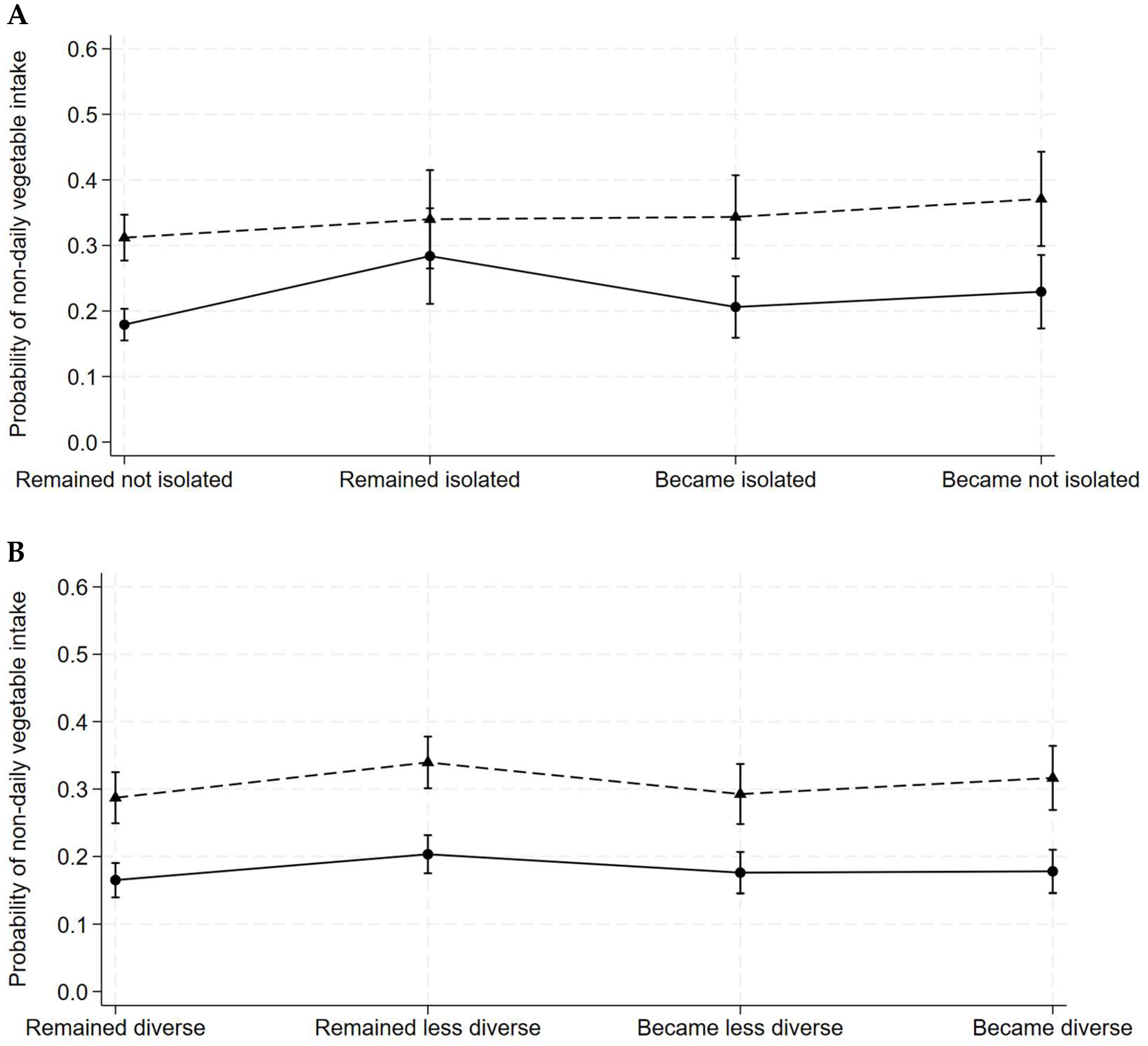

3.1. Social Isolation and Social Participation Transitions Associated with Reduced Vegetable Intake by Gender

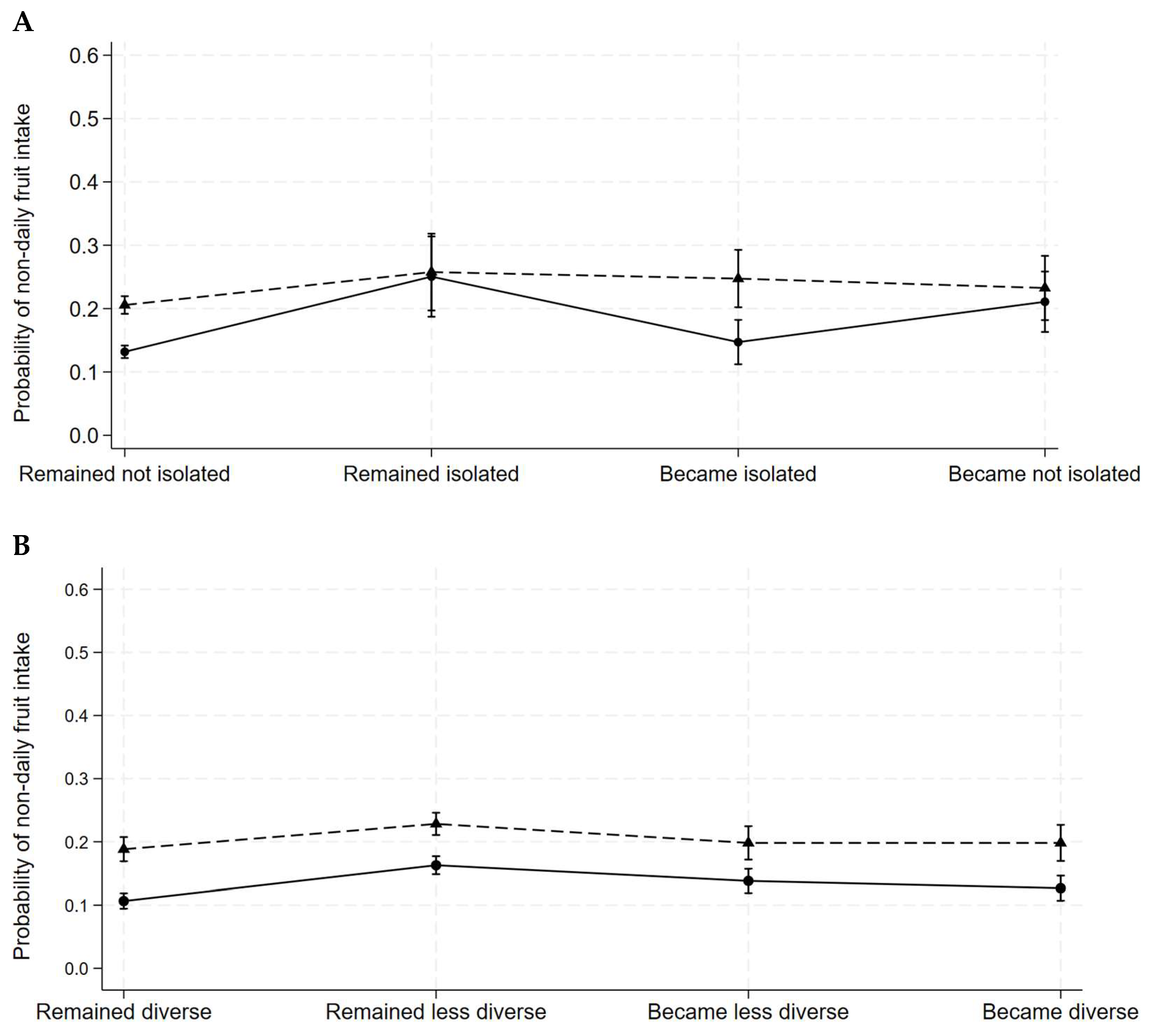

3.2. Social Isolation and Social Participation Transitions Associated with Reduced Fruit Intake by Gender

4. Discussion

4.1. Relevance to Previous Research

4.2. Methodological Considerations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CLSA | Canadian Longitudinal Study on Aging |

| FV | fruit and vegetable |

| F/V | fruit or vegetable |

| BMI | body mass index |

| SDQ | Short Dietary Questionnaire |

| FFQ | food frequency questionnaire |

| GDP | gross domestic product |

| OR | odds ratios |

| CI95 | 95% confidence intervals |

References

- World Health Organization. Ageing and Health. 2022. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/ageing-and-health (accessed on 12 June 2024).

- Statistics Canada. Seniors. Available online: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/11-402-x/2011000/chap/seniors-aines/seniors-aines-eng.htm (accessed on 12 June 2024).

- Lee, H.Y.; Jang, S.N.; Lee, S.; Cho, S.I.; Park, E.O. The relationship between social participation and self-rated health by sex and age: A cross-sectional survey. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2008, 45, 1042–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keefe, J.; Fancey, P.; Andrew, M.; Hall, M. A Profile of Social Isolation in Canada. Prepared for Federal/Provincial/Territorial Committee of Officials (Seniors). 2006. Available online: https://www.canada.ca/en/national-seniors-council/programs/publications-reports/2014/social-isolation-seniors/page03.html (accessed on 12 June 2024).

- International Federation of Aging. Current and Emerging Issues Facing Older Canadians; International Federation of Aging: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Levasseur, M.; Richard, L.; Gauvin, L.; Raymond, E. Inventory and analysis of definitions of social participation found in the aging literature: Proposed taxonomy of social activities. Soc. Sci. Med. 2010, 71, 2141–2149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hämmig, O. Health risks associated with social isolation in general and in young, middle and old age. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0219663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holt-Lunstad, J.; Smith, T.B.; Layton, J.B. Social relationships and mortality risk: A meta-analytic review. PLoS Med. 2010, 7, e1000316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sowa, A.; Tobiasz-Adamczyk, B.; Topór-Mądry, R.; Poscia, A.; la Milia, D.I. Predictors of healthy ageing: Public health policy targets. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2016, 16, 289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilmour, H. Social participation and the health and well-being of Canadian seniors. Health Rep. 2012, 23, 23–32. [Google Scholar]

- Holt-Lunstad, J.; Smith, T.B.; Baker, M.; Harris, T.; Stephenson, D. Loneliness and social isolation as risk factors for mortality: A meta-analytic review. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2015, 10, 227–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilmour, H.; Ramage-Morin, P.L. Social isolation and mortality among Canadian seniors. Health Rep. 2020, 31, 27–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shankar, A.; McMunn, A.; Banks, J.; Steptoe, A. Loneliness, social isolation, and behavioral and biological health indicators in older adults. Health Psychol. 2011, 30, 377–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delerue Matos, A.; Barbosa, F.; Cunha, C.; Voss, G.; Correia, F. Social isolation, physical inactivity and inadequate diet among European middle-aged and older adults. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menec, V.H.; Newall, N.E.; Mackenzie, C.S.; Shooshtari, S.; Nowicki, S. Examining individual and geographic factors associated with social isolation and loneliness using Canadian Longitudinal Study on Aging (CLSA) data. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0211143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valtorta, N.K.; Kanaan, M.; Gilbody, S.; Hanratty, B. Loneliness, social isolation and risk of cardiovascular disease in the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 2018, 25, 1387–1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.C.; Boen, C.; Gerken, K.; Li, T.; Schorpp, K.; Harris, K.M. Social relationships and physiological determinants of longevity across the human life span. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, 578–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schram, M.T.; Assendelft, W.J.J.; van Tilburg, T.G.; Dukers-Muijrers, N. Social networks and type 2 diabetes: A narrative review. Diabetologia 2021, 64, 1905–1916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holt-Lunstad, J.; Robles, T.F.; Sbarra, D.A. Advancing social connection as a public health priority in the United States. Am. Psychol. 2017, 72, 517–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, Z.; Veenstra, G.; Khan, N.A.; Conklin, A.I. Social connections and hypertension in women and men: A population-based cross-sectional study of the Canadian Longitudinal Study on Aging. J. Hypertens. 2021, 39, 651–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hosseini, Z.; Veenstra, G.; Khan, N.A.; Conklin, A.I. Associations between social connections, their interactions, and obesity differ by gender: A population-based, cross-sectional analysis of the Canadian Longitudinal Study on Aging. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0235977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hosseini, Z.; Safari, A.; Khan, N.A.; Veenstra, G.; Conklin, A.I. Adiposity and the role of diverse social supports: An observational, gender-sensitive study using the baseline Canadian Longitudinal Study on Aging. Public Health Nutr. 2021, 24, 6103–6112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hosseini, Z.; Safari, A.; Khan, N.A.; Veenstra, G.; Conklin, A.I. Gender Differences in the Role of Social Support for Hypertension Prevention in Canada: A Population-Based Cross-Sectional Study of the Canadian Longitudinal Study on Aging Cohort. CJC Open 2021, 3, S62–S70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkman, L.F.; Glass, T.; Brissette, I.; Seeman, T.E. From social integration to health: Durkheim in the new millennium. Soc. Sci. Med. 2000, 51, 843–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanna, K.; Cross, J.; Nicholls, A.; Gallegos, D. The association between loneliness or social isolation and food and eating behaviours: A scoping review. Appetite 2023, 191, 107051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgs, S.; Thomas, J. Social influences on eating. Curr. Opin. Behav. Sci. 2016, 9, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saif, N.T.; Addison, O.R.; Hughes Barry, K.; Falvey, J.R.; Parker, E.A. Associations between social isolation and diet quality among US adults with disability participating in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2013–2018. Prev. Med. Rep. 2023, 36, 102413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalousova, L. Social isolation as a risk factor for inadequate diet of older Eastern Europeans. Int. J. Public Health 2014, 59, 707–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, L.C.; Steptoe, A. Social Isolation, Loneliness, and Health Behaviors at Older Ages: Longitudinal Cohort Study. Ann. Behav. Med. 2018, 52, 582–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steptoe, A.; Fong, H.L.; Lassale, C. Social isolation, loneliness and low dietary micronutrient intake amongst older people in England. Age Ageing 2024, 53, afae223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conklin, A.I.; Forouhi, N.G.; Surtees, P.; Khaw, K.T.; Wareham, N.J.; Monsivais, P. Social relationships and healthful dietary behaviour: Evidence from over-50s in the EPIC cohort, UK. Soc. Sci. Med. 2014, 100, 167–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, C.M.; Keller, H.H.; DePaul, V.G.; Donnelly, C. Social Network Factors Affect Nutrition Risk in Middle-Aged and Older Adults: Results from the Canadian Longitudinal Study on Aging. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2023, 27, 46–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloom, I.; Edwards, M.; Jameson, K.A.; Syddall, H.E.; Dennison, E.; Gale, C.R.; Baird, J.; Cooper, C.; Aihie Sayer, A.; Robinson, S. Influences on diet quality in older age: The importance of social factors. Age Ageing 2017, 46, 277–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishio, M.; Takagi, D.; Shinozaki, T.; Kondo, N. Community social networks, individual social participation and dietary behavior among older Japanese adults: Examining mediation using nonlinear structural equation models for three-wave longitudinal data. Prev. Med. 2021, 149, 106613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehranfar, S.; Madani Civi, R.; Plunkett, R.; Murphy, R.A.; Cohen, T.R.; Conklin, A.I. The Longitudinal Evidence on Social Ties and Fruit and Vegetable Intake among Aging Adults: A Systematic Review. Nutr. Rev. 2024, nuae134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feraco, A.; Armani, A.; Amoah, I.; Guseva, E.; Camajani, E.; Gorini, S.; Strollo, R.; Padua, E.; Caprio, M.; Lombardo, M. Assessing gender differences in food preferences and physical activity: A population-based survey. Front. Nutr. 2024, 11, 1348456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naud, D.; Généreux, M.; Alauzet, A.; Bruneau, J.F.; Cohen, A.; Levasseur, M. Social participation and barriers to community activities among middle-aged and older Canadians: Differences and similarities according to gender and age. Geriatr. Gerontol. Int. 2021, 21, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raina, P.; Wolfson, C.; Kirkland, S.; Griffith, L.E.; Balion, C.; Cossette, B.; Dionne, I.; Hofer, S.; Hogan, D.; van den Heuvel, E.R.; et al. Cohort Profile: The Canadian Longitudinal Study on Aging (CLSA). Int. J. Epidemiol. 2019, 48, 1752–1753j. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raina, P.S.; Wolfson, C.; Kirkland, S.A.; Griffith, L.E.; Oremus, M.; Patterson, C.; Tuokko, H.; Penning, M.; Balion, C.M.; Hogan, D.; et al. The Canadian longitudinal study on aging (CLSA). Can. J. Aging 2009, 28, 221–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raina, P.; Wolfson, C.; Kirkland, S. Canadian Longitudinal Study on Aging (CLSA) Protocol Version 3.0. 2008. Available online: https://www.clsa-elcv.ca/researchers (accessed on 26 April 2024).

- 2023 CLSA Sampling and Computation of Response Rates and Sample Weights for the Tracking (Telephone Interview) Participants and Comprehensive Participants (Version 2.0). Available online: https://www.clsa-elcv.ca/our-resources/2023-sampling-and-computation-of-response-rates-and-sample-weights-for-the-tracking-telephone-interview-participants-and-comprehensive-participants/ (accessed on 26 April 2024).

- Lachat, C.; Hawwash, D.; Ocké, M.C.; Berg, C.; Forsum, E.; Hörnell, A.; Larsson, C.; Sonestedt, E.; Wirfält, E.; Åkesson, A.; et al. Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology-Nutritional Epidemiology (STROBE-nut): An Extension of the STROBE Statement. PLoS Med. 2016, 13, e1002036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shatenstein, B.; Payette, H. Evaluation of the Relative Validity of the Short Diet Questionnaire for Assessing Usual Consumption Frequencies of Selected Nutrients and Foods. Nutrients 2015, 7, 6362–6374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canada’s Food Guide. Eat Vegetables and Fruits. Available online: https://food-guide.canada.ca/en/healthy-eating-recommendations/make-it-a-habit-to-eat-vegetables-fruit-whole-grains-and-protein-foods/eat-vegetables-and-fruits/ (accessed on 20 March 2024).

- NIH National Cancer Institute. Identifying Extreme Exposure Values. 2021. Available online: https://epi.grants.cancer.gov/nhanes/dietscreen/scoring/current/identify.html (accessed on 20 March 2024).

- Ceolin, G.; Veenstra, G.; Mehranfar, S.; Civi, R.M.; Khan, N.A.; Conklin, A.I. Trends, transitions and patterning in social activity over time among aging women and men: A secondary analysis of the Canadian Longitudinal Study on Aging (CLSA). Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2024, 128, 105618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Textor, J.; van der Zander, B.; Gilthorpe, M.S.; Liśkiewicz, M.; Ellison, G.T. Robust causal inference using directed acyclic graphs: The R package ‘dagitty’. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2017, 45, 1887–1894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, D.; Gale, J.; Bauman, A.; Phongsavan, P.; Nguyen, B. Effects of divorce and widowhood on subsequent health behaviours and outcomes in a sample of middle-aged and older Australian adults. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 15237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eng, P.M.; Kawachi, I.; Fitzmaurice, G.; Rimm, E.B. Effects of marital transitions on changes in dietary and other health behaviours in US male health professionals. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2005, 59, 56–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.; Cho, E.; Grodstein, F.; Kawachi, I.; Hu, F.B.; Colditz, G.A. Effects of marital transitions on changes in dietary and other health behaviours in US women. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2005, 34, 69–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noguchi, T.; Kondo, F.; Nishiyama, T.; Otani, T.; Nakagawa-Senda, H.; Watanabe, M.; Imaeda, N.; Goto, C.; Hosono, A.; Shibata, K.; et al. The Impact of Marital Transitions on Vegetable Intake in Middle-aged and Older Japanese Adults: A 5-year Longitudinal Study. J. Epidemiol. 2022, 32, 89–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plessz, M.; Gueguen, A. Who Benefits from Living in a Couple? A Longitudinal Study of Eating Practices at the Intersection of Gender, Conjugal Situation, and Social Status. Rev. Fr. Sociol. (Engl. Ed.) 2017, 58, 1–29. [Google Scholar]

- Vinther, J.L.; Conklin, A.I.; Wareham, N.J.; Monsivais, P. Marital transitions and associated changes in fruit and vegetable intake: Findings from the population-based prospective EPIC-Norfolk cohort, UK. Soc. Sci. Med. 2016, 157, 120–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilcox, S.; Evenson, K.R.; Aragaki, A.; Wassertheil-Smoller, S.; Mouton, C.P.; Loevinger, B.L. The effects of widowhood on physical and mental health, health behaviors, and health outcomes: The Women’s Health Initiative. Health Psychol. 2003, 22, 513–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikram, M.A. The disjunctive cause criterion by VanderWeele: An easy solution to a complex problem? Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2019, 34, 223–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollack, C.E.; Chideya, S.; Cubbin, C.; Williams, B.; Dekker, M.; Braveman, P. Should health studies measure wealth? A systematic review. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2007, 33, 250–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tannenbaum, C.; Greaves, L.; Graham, I.D. Why sex and gender matter in implementation research. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2016, 16, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- STATA. Melogit—Multilevel Mixed-Effects Logistic Regression. Available online: https://www.stata.com/manuals13/memelogit.pdf (accessed on 28 April 2024).

- Bassim, C.; Mayhew, A.J.; Ma, J.; Kanters, D.; Verschoor, C.P.; Griffith, L.E.; Raina, P. Oral Health, Diet, and Frailty at Baseline of the Canadian Longitudinal Study on Aging. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2020, 68, 959–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palaniappan, U.; Starkey, L.J.; O’Loughlin, J.; Gray-Donald, K. Fruit and Vegetable Consumption Is Lower and Saturated Fat Intake Is Higher among Canadians Reporting Smoking. J. Nutr. 2001, 131, 1952–1958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kesse, E.; Clavel-Chapelon, F.; Slimani, N.; van Liere, M. Do eating habits differ according to alcohol consumption? Results of a study of the French cohort of the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (E3N-EPIC)1234. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2001, 74, 322–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marino, M.; Masella, R.; Bulzomi, P.; Campesi, I.; Malorni, W.; Franconi, F. Nutrition and human health from a sex–gender perspective. Mol. Asp. Med. 2011, 32, 1–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamarche, B.; Brassard, D.; Lapointe, A.; Laramée, C.; Kearney, M.; Côté, M.; Bélanger-Gravel, A.; Desroches, S.; Lemieux, S.; Plante, C. Changes in diet quality and food security among adults during the COVID-19-related early lockdown: Results from NutriQuébec. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2021, 113, 984–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payette, H.; Shatenstein, B. Determinants of healthy eating in community-dwelling elderly people. Can. J. Public Health 2005, 96 (Suppl. S3), S30–S35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conklin, A.I.; Forouhi, N.G.; Surtees, P.; Wareham, N.J.; Monsivais, P. Gender and the double burden of economic and social disadvantages on healthy eating: Cross-sectional study of older adults in the EPIC-Norfolk cohort. BMC Public Health 2015, 15, 692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wister, A.; Cosco, T.; Mitchell, B.; Menec, V.; Fyffe, I. Development and Concurrent Validity of a Composite Social Isolation Index for Older Adults Using the CLSA. Can. J. Aging 2019, 38, 180–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barr, E.; Popkin, R.; Roodzant, E.; Jaworski, B.; Temkin, S.M. Gender as a social and structural variable: Research perspectives from the National Institutes of Health (NIH). Transl. Behav. Med. 2024, 14, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conklin, A.I. Gender, Diet Quality and Obesity: Economic and Social Determinants, and Their Interactions, in Older Adults. 2014. Available online: https://www.repository.cam.ac.uk/handle/1810/262808 (accessed on 12 June 2024).

- Statistics Canada. The Economic Well-Being of Women in Canada. Available online: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/en/pub/89-503-x/2015001/article/54930-eng.pdf?st=iLTNjJ0a (accessed on 23 September 2024).

- Leopold, T. Gender Differences in the Consequences of Divorce: A Study of Multiple Outcomes. Demography 2018, 55, 769–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tucker, J.S. Health-Related Social Control Within Older Adults’ Relationships. J. Gerontol. Ser. B 2002, 57, P387–P395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emmons, K.M.; Barbeau, E.M.; Gutheil, C.; Stryker, J.E.; Stoddard, A.M. Social Influences, Social Context, and Health Behaviors Among Working-Class, Multi-Ethnic Adults. Health Educ. Behav. 2007, 34, 315–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, T. Gambling and Drinking, Do They Go Hand in Hand? The Impact of Drinking on Gambling Behaviors and Game Outcomes in Texas Hold’em Poker Short Game. In New Perspectives and Paradigms in Applied Economics and Business; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 219–251. [Google Scholar]

- Government of Canada Publications. Sport Participation 2010. Available online: https://publications.gc.ca/collections/collection_2013/pc-ch/CH24-1-2012-eng.pdf (accessed on 4 October 2024).

- Courtney, J.; Handley, E.; Pagoto, S.; Russell, M.; Conroy, D.E. Alcohol use as a function of physical activity and golfing motives in a national sample of United States golfers. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reynolds, K.A.; Sommer, J.; Mackenzie, C.S.; Koven, L. A Profile of Social Participation in a Nationally Representative Sample of Canadian Older Adults: Findings from the Canadian Longitudinal Study on Aging. Can. J. Aging 2022, 41, 505–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramage-Morin, P.L.; Garriguet, D. Nutritional risk among older Canadians. Health Rep. 2013, 24, 3–13. [Google Scholar]

- Holt-Lunstad, J. National Health Guidelines for Social Connection: What Is the Evidence in Support and What Might the Guidelines Say? Policy Insights Behav. Brain Sci. 2023, 10, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohn-Schwartz, E.; Schmitz, A. From attitudes to social networks: National gender-role attitudes and gender differences in late-life social relationships. Soc. Netw. 2024, 76, 79–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, H.; Park, C. Gender differences in social networks and physical and mental health: Are social relationships more health protective in women than in men? Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1216032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedrov, A.; Gable, S.L. Thriving together: The benefits of women’s social ties for physical, psychological and relationship health. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 2023, 378, 20210441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finkel, D.; Andel, R.; Pedersen, N.L. Gender Differences in Longitudinal Trajectories of Change in Physical, Social, and Cognitive/Sedentary Leisure Activities. J. Gerontol. Ser. B 2016, 73, 1491–1500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeVault, M. Conflict and Deference. In Feeding the Family; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1991; pp. 138–166. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, S.E.; Klein, L.C.; Lewis, B.P.; Gruenewald, T.L.; Gurung, R.A.; Updegraff, J.A. Biobehavioral responses to stress in females: Tend-and-befriend, not fight-or-flight. Psychol. Rev. 2000, 107, 411–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edwards, O.; Mawani, A. Healthy Aging in Canada: A New Vision, a Vital Investment from Evidence to Action; Public Health Agency of Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2006.

- Hill, A.B. The environment and disease: Association or causation? Proc. R. Soc. Med. 1965, 58, 295–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Social Isolation Transitions | Mean (SD) Age (Years) | Highest Education 1 | Highest Household Income 2 | Home-Owner | Urban Location | BMI (kg/m2) | No Chronic Condition | Not Sleep Deprived | Non-Daily Vegetable Intake |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Women | |||||||||

| Remained not isolated (n = 8615) | 59.09 (9.83) | 6937 (67.5%) | 1390 (17.1%) | 7524 (87.4%) | 7729 (92.2%) | 27.52 (5.89) | 463 (6.6%) | 5503 (63.0%) | 1532 (16.1%) |

| Remained isolated (n = 163) | 63.56 (10.42) | 98 (39.7%) | 8 (9.9%) | 110 (67.6%) | 142 (93.2%) | 28.05 (5.78) | 8 (4.4%) | 94 (51.1%) | 53 (27.7%) |

| Became isolated (n = 366) | 59.72 (11.18) | 250 (51.8%) | 34 (8.5%) | 281 (77.2%) | 324 (94.1%) | 28.90 (6.84) | 9 (1.5%) | 197 (54.7%) | 84 (26.1%) |

| Became not isolated (n = 257) | 58.50 (8.7) | 162 (47.7%) | 25 (9.2%) | 192 (70.1%) | 233 (95.1%) | 28.20 (6.72) | 14 (14.5%) | 149 (54.4%) | 66 (19.1%) |

| Men | |||||||||

| Remained not isolated (n = 5907) | 58.82 (9.92) | 4989 (70.9%) | 1371 (23.4%) | 5341 (88.0%) | 5330 (94.4%) | 27.92 (4.55) | 429 (9.2%) | 3877 (64.2%) | 1754 (27.7%) |

| Remained isolated (n = 181) | 61.77 (9.06) | 130 (62.0%) | 14 (5.9%) | 145 (78.0%) | 164 (93.0%) | 28.89 (5.79) | 5 (2.6%) | 103 (59.8%) | 66 (29.4%) |

| Became isolated (n = 292) | 59.12 (8.79) | 234 (68.2%) | 41 (18.9%) | 236 (75.9%) | 258 (95.7%) | 28.19 (5.65) | 26 (9.1%) | 181 (64.6%) | 102 (34.6%) |

| Became not isolated (n = 218) | 58.63 (10.62) | 159 (49.8%) | 30 (9.6%) | 177 (75.1%) | 191 (93.9%) | 28.96 (5.30) | 14 (3.6%) | 136 (55.7%) | 84 (43.9%) |

| Social Participation Transitions | Age (Years) | Highest Education 1 | Highest Household Income 2 | Home-Owner | Urban Location | BMI (kg/m2) | No Chronic Condition | Not Sleep Deprived | Non-Daily Vegetable Intake |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Women | |||||||||

| Remained diverse (n = 3152) | 60.68 (10.18) | 2675 (74.7%) | 521 (18.9%) | 2817 (89.8%) | 2856 (92.6%) | 27.36 (5.75) | 160 (6.6%) | 2073 (66.9%) | 503 (14.6%) |

| Remained less diverse (n = 3857) | 58.43 (9.7) | 2852 (61.1%) | 574 (15.1%) | 3228 (82.7%) | 3406 (92.1%) | 27.89 (6.18) | 207 (7.2%) | 2353 (57.9%) | 809 (19.7%) |

| Became less diverse (n = 1294) | 58.63 (10.09) | 1035 (62.0%) | 192 (15.0%) | 1105 (87.9%) | 1173 (91.7%) | 27.61 (5.9) | 70 (4.7%) | 804 (63.2%) | 228 (15.0%) |

| Became diverse (n = 1098) | 59.91 (9.44) | 885 (65.3%) | 170 (16.2%) | 957 (86.5%) | 993 (94.2%) | 27.15 (5.6) | 57 (6.1%) | 713 (66.7%) | 195 (14.2%) |

| Men | |||||||||

| Remained diverse (n = 1894) | 60.29 (10.49) | 1661 (74.5%) | 459 (25.4%) | 1717 (90.0%) | 1716 (93.6%) | 28.73 (4.89) | 137 (9.7%) | 1258 (63.3%) | 515 (23.2%) |

| Remained less diverse (n = 3145) | 58.08 (9.39) | 2523 (65.5%) | 634 (20.6%) | 2752 (83.0%) | 2810 (94.5%) | 27.63 (4.59) | 235 (9.0%) | 2012 (63.1%) | 1040 (33.1%) |

| Became less diverse (n = 832) | 59.28 (10.37) | 704 (71.7%) | 208 (21.7%) | 757 (90.8%) | 756 (94.4%) | 28.15 (4.53) | 48 (6.4%) | 529 (68.1%) | 231 (22.5%) |

| Became diverse (n = 727) | 59.53 (9.97) | 624 (76.1%) | 155 (21.7%) | 673 (91.0%) | 661 (95.7%) | 28.11 (4.72) | 54 (8.3%) | 498 (62.1%) | 220 (28.1%) |

| Model A | Model B | Model C | Model D | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | CI95 | OR | CI95 | OR | CI95 | OR | CI95 | |

| Women | ||||||||

| Remained not isolated | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | ||||

| Remained isolated | 2.10 *** | [1.51, 2.94] | 1.85 *** | [1.32, 2.59] | 1.85 *** | [1.31, 2.59] | 1.85 *** | [1.32, 2.59] |

| Became isolated | 1.32 * | [1.02, 1.69] | 1.20 | [0.93, 1.55] | 1.19 | [0.93, 1.54] | 1.19 | [0.93, 1.54] |

| Became not isolated | 1.50 ** | [1.13, 2.01] | 1.36 * | [1.02, 1.82] | 1.37 * | [1.03, 1.84] | 1.38 * | [1.03, 1.84] |

| Men | ||||||||

| Remained not isolated | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | ||||

| Remained isolated | 1.32 | [0.97, 1.80] | 1.16 | [0.85, 1.59] | 1.14 | [0.83, 1.56] | 1.14 | [0.83, 1.56] |

| Became isolated | 1.25 | [0.98, 1.61] | 1.16 | [0.90, 1.50] | 1.16 | [0.90, 1.49] | 1.16 | [0.90, 1.49] |

| Became not isolated | 1.42 * | [1.07, 1.88] | 1.32 | [0.99, 1.75] | 1.31 | [0.99, 1.75] | 1.31 | [0.99, 1.74] |

| Model A | Model B | Model C | Model D | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | CI95 | OR | CI95 | OR | CI95 | OR | CI95 | |

| Women | ||||||||

| Remained diverse | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | ||||

| Remained less diverse | 1.36 * | [1.20, 1.54] | 1.29 * | [1.14, 1.47] | 1.30 * | [1.15, 1.48] | 1.30 * | [1.15, 1.47] |

| Became less diverse | 1.12 | [0.94, 1.33] | 1.08 | [0.91, 1.29] | 1.08 | [0.91, 1.29] | 1.08 | [0.91, 1.29] |

| Became diverse | 1.12 | [0.93, 1.34] | 1.09 | [0.91, 1.31] | 1.10 | [0.91, 1.32] | 1.10 | [0.91, 1.32] |

| Men | ||||||||

| Remained diverse | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | ||||

| Remained less diverse | 1.36 * | [1.20, 1.55] | 1.29 * | [1.13, 1.46] | 1.29 * | [1.13, 1.46] | 1.29 * | [1.13, 1.46] |

| Became less diverse | 1.04 | [0.87, 1.25] | 1.03 | [0.85, 1.24] | 1.03 | [0.85, 1.24] | 1.03 | [0.85, 1.24] |

| Became diverse | 1.18 | [0.98, 1.43] | 1.15 | [0.95, 1.40] | 1.16 | [0.95, 1.40] | 1.16 | [0.95, 1.4] |

| Model A | Model B | Model C | Model D | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | CI95 | OR | CI95 | OR | CI95 | OR | CI95 | |

| Women | ||||||||

| Remained not isolated | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | ||||

| Remained isolated | 2.42 ** | [1.72, 3.40] | 2.19 ** | [1.56, 3.08] | 2.23 ** | [1.58, 3.14] | 2.23 ** | [1.58, 3.14] |

| Became isolated | 1.19 | [0.90, 1.57] | 1.14 | [0.86, 1.50] | 1.14 | [0.86, 1.51] | 1.14 | [0.86, 1.51] |

| Became not isolated | 1.88 ** | [1.41, 2.51] | 1.76 ** | [1.32, 2.35] | 1.77 ** | [1.33, 2.37] | 1.77 ** | [1.33, 2.37] |

| Men | ||||||||

| Remained not isolated | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | ||||

| Remained isolated | 1.46 * | [1.06, 2.01] | 1.35 | [0.98, 1.87] | 1.35 | [0.98, 1.86] | 1.35 | [0.98, 1.86] |

| Became isolated | 1.32 * | [1.03, 1.68] | 1.28 | [1.00, 1.63] | 1.27 | [1.00, 1.63] | 1.27 | [1.00, 1.63] |

| Became not isolated | 1.21 | [0.91, 1.62] | 1.17 | [0.88, 1.56] | 1.17 | [0.88, 1.57] | 1.17 | [0.88, 1.57] |

| Model A | Model B | Model C | Model D | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | CI95 | OR | CI95 | OR | CI95 | OR | CI95 | |

| Women | ||||||||

| Remained diverse | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | ||||

| Remained less diverse | 1.71 *** | [1.49, 1.96] | 1.63 *** | [1.42, 1.87] | 1.64 *** | [1.43, 1.88] | 1.64 *** | [1.43, 1.88] |

| Became less diverse | 1.37 ** | [1.14, 1.65] | 1.34 ** | [1.12, 1.62] | 1.35 ** | [1.12, 1.62] | 1.35 ** | [1.12, 1.62] |

| Became diverse | 1.24 * | [1.01, 1.51] | 1.21 | [0.99, 1.48] | 1.22 | [1.00, 1.49] | 1.22 | [1.00, 1.49] |

| Men | ||||||||

| Remained diverse | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | ||||

| Remained less diverse | 1.32 *** | [1.16, 1.51] | 1.28 *** | [1.12, 1.46] | 1.28 *** | [1.12, 1.46] | 1.28 *** | [1.12, 1.46] |

| Became less diverse | 1.07 | [0.89, 1.30] | 1.07 | [0.88, 1.29] | 1.07 | [0.88, 1.29] | 1.07 | [0.88, 1.29] |

| Became diverse | 1.10 | [0.90, 1.34] | 1.08 | [0.88, 1.32] | 1.07 | [0.87, 1.30] | 1.07 | [0.87, 1.30] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mehranfar, S.; Ceolin, G.; Madani Civi, R.; Keller, H.; Murphy, R.A.; Cohen, T.R.; Conklin, A.I. Gender, Adverse Changes in Social Engagement and Risk of Unhealthy Eating: A Prospective Cohort Study of the Canadian Longitudinal Study on Aging (2011–2021). Nutrients 2025, 17, 1005. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17061005

Mehranfar S, Ceolin G, Madani Civi R, Keller H, Murphy RA, Cohen TR, Conklin AI. Gender, Adverse Changes in Social Engagement and Risk of Unhealthy Eating: A Prospective Cohort Study of the Canadian Longitudinal Study on Aging (2011–2021). Nutrients. 2025; 17(6):1005. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17061005

Chicago/Turabian StyleMehranfar, Sanaz, Gilciane Ceolin, Rana Madani Civi, Heather Keller, Rachel A. Murphy, Tamara R. Cohen, and Annalijn I. Conklin. 2025. "Gender, Adverse Changes in Social Engagement and Risk of Unhealthy Eating: A Prospective Cohort Study of the Canadian Longitudinal Study on Aging (2011–2021)" Nutrients 17, no. 6: 1005. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17061005

APA StyleMehranfar, S., Ceolin, G., Madani Civi, R., Keller, H., Murphy, R. A., Cohen, T. R., & Conklin, A. I. (2025). Gender, Adverse Changes in Social Engagement and Risk of Unhealthy Eating: A Prospective Cohort Study of the Canadian Longitudinal Study on Aging (2011–2021). Nutrients, 17(6), 1005. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17061005