Dietary Supplementation for Fatigue Symptoms in Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS)—A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome

1.2. ME/CFS and Dietary Supplementation

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Literature Search

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

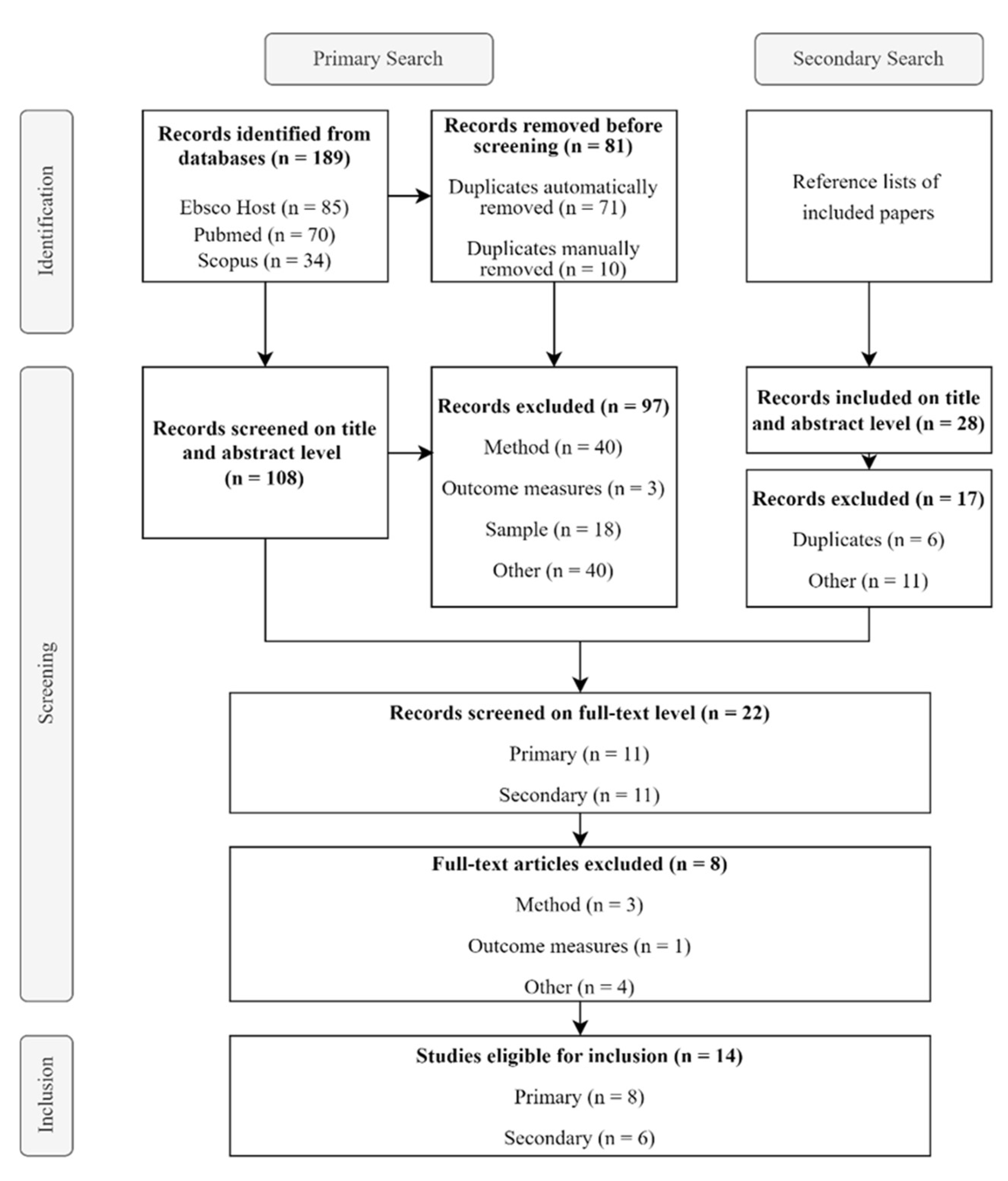

2.3. Selection of Studies

2.4. Data Extraction and Quality Assessment

3. Results

3.1. Overview of Studies and Study Quality

3.2. Participant and Study Characteristics

3.3. Primary Outcome: Fatigue

3.4. Secondary Outcomes

3.4.1. Patient-Reported Outcome Measures (PROMs)

3.4.2. Physiological Parameters

3.4.3. Laboratory Parameters

3.5. Adverse Effects and Comorbidities

4. Discussion

4.1. Attempts to Unravel the Complexities of ME/CFS: Exploring Immune Dysregulation, Mitochondrial Dysfunction, and Potential Therapeutic Interventions

4.2. Addressing Bias and Improving Representation in ME/CFS Research: The Need for Larger, Inclusive Studies and Flexible Recruitment Methods

4.3. Addressing Comorbidities in ME/CFS Research: The Importance of Including Comorbidities and Concomitant Medications for Comprehensive Treatment Evaluation

4.4. Improving ME/CFS Research: The Need for Updated Diagnostic Criteria, Standardized Fatigue Assessment, and Rigorous Washout Periods in Clinical Trials

4.5. Variability in Washout Periods and Their Impact on Clinical Trials for DSs in ME/CFS: Urgent Need for Standardization

4.6. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cortes Rivera, M.; Mastronardi, C.; Silva-Aldana, C.T.; Arcos-Burgos, M.; Lidbury, B.A. Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome: A Comprehensive Review. Diagnostics 2019, 9, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finsterer, J.; Mahjoub, S.Z. Fatigue in healthy and diseased individuals. Am. J. Hosp. Palliat. Care 2014, 31, 562–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, T.L.; Weitzer, D.J. Long COVID and Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS)-A Systemic Review and Comparison of Clinical Presentation and Symptomatology. Medicina 2021, 57, 418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, E.-J.; Ahn, Y.-C.; Jang, E.-S.; Lee, S.-W.; Lee, S.-H.; Son, C.-G. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the prevalence of chronic fatigue syndrome/myalgic encephalomyelitis (CFS/ME). J. Transl. Med. 2020, 18, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Renz-Polster, H.; Scheibenbogen, C. Post-COVID syndrome with fatigue and exercise intolerance: Myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome. Inn. Med. 2022, 63, 830–839. [Google Scholar]

- Bakken, I.J.; Tveito, K.; Gunnes, N.; Ghaderi, S.; Stoltenberg, C.; Trogstad, L.; Haberg, S.E.; Magnus, P. Two age peaks in the incidence of chronic fatigue syndrome/myalgic encephalomyelitis: A population-based registry study from Norway 2008–2012. BMC Med. 2014, 12, 167. [Google Scholar]

- Chu, L.; Valencia, I.J.; Garvert, D.W.; Montoya, J.G. Onset Patterns and Course of Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome. Front. Pediatr. 2019, 7, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Estevez-Lopez, F.; Castro-Marrero, J.; Wang, X.; Bakken, I.J.; Ivanovs, A.; Nacul, L.; Sepulveda, N.; Strand, E.B.; Pheby, D.; Alegre, J.; et al. Prevalence and incidence of myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome in Europe-the Euro-epiME study from the European network EUROMENE: A protocol for a systematic review. BMJ Open 2018, 8, e020817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Komaroff, A.L.; Bateman, L. Will COVID-19 Lead to Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Synrome? Front. Med. 2020, 7, 606824. [Google Scholar]

- Clayton, E.W. Beyond myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome: An IOM report on redefining an illness. JAMA 2015, 313, 1101–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nacul, L.; Authier, F.J.; Scheibenbogen, C.; Lorusso, L.; Helland, I.B.; Martin, J.A.; Sirbu, C.A.; Mengshoel, A.M.; Polo, O.; Behrends, U.; et al. European Network on Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (EUROMENE): Expert Consensus on the Diagnosis, Service Provision, and Care of People with ME/CFS in Europe. Medicina 2021, 57, 510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacerda, E.M.; McDermott, C.; Kingdon, C.C.; Butterworth, J.; Cliff, J.M.; Nacul, L. Hope, disappointment and perseverance: Reflections of people with Myalgic encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS) and Multiple Sclerosis participating in biomedical research. A qualitative focus group study. Health Expect. Int. J. Public Particip. Health Care Health Policy 2019, 22, 373–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stussman, B.; Williams, A.; Snow, J.; Gavin, A.; Scott, R.; Nath, A.; Walitt, B. Characterization of Post-exertional Malaise in Patients With Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome. Front. Neurol 2020, 11, 1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, K.; Hainzl, A.; Stingl, M.; Kurz, K.; Biesenbach, B.; Bammer, C.; Behrends, U.; Broxtermann, W.; Buchmayer, F.; Cavini, A.M.; et al. Interdisciplinary, collaborative D-A-CH (Germany, Austria and Switzerland) consensus statement concerning the diagnostic and treatment of myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome. Wien. Klin. Wochenschr. 2024, 136 (Suppl. 5), 103–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montoya, J.G.; Dowell, T.G.; Mooney, A.E.; Dimmock, M.E.; Chu, L. Caring for the Patient with Severe or Very Severe Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome. Healthcare 2021, 9, 1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simon, G.E.; VonKorff, M.; Piccinelli, M.; Fullerton, C.; Ormel, J. An international study of the relation between somatic symptoms and depression. N. Engl. J. Med. 1999, 341, 1329–1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maes, M. “Functional” or “psychosomatic” symptoms, eg a flu-like malaise, aches and pain and fatigue, are major features of major and in particular of melancholic depression. Neuroendocrinol. Lett. 2009, 30, 564. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Fukuda, K.; Straus, S.E.; Hickie, I.; Sharpe, M.C.; Dobbins, J.G.; Komaroff, A. The chronic fatigue syndrome: A comprehensive approach to its definition and study. Ann. Intern. Med. 1994, 121, 953–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carruthers, B.M.; van de Sande, M.I.; De Meirleir, K.L.; Klimas, N.G.; Broderick, G.; Mitchell, T.; Staines, D.; Powles, A.C.; Speight, N.; Vallings, R.; et al. Myalgic encephalomyelitis: International Consensus Criteria. J. Intern. Med. 2011, 270, 327–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Institute of Medicine; Board on the Health of Select Populations. Committee on the Diagnostic Criteria for Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Sydrome. In The National Academies Collection: Reports funded by National Institutes of Health, Beyond Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome: Redefining an Illness; National Academies Press (US): Washington, DC, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Jason, L.A.; Evans, M.; Porter, N.; Brown, M.; Brown, A.; Hunnell, J.; Anderson, V.; Lerch, A.; De Meirleir, K.; Friedberg, F. The Development of a Revised Canadian Myalgic Encephalomyelitis Chronic Fatigue Syndrome Case Definition. Am. J. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2010, 6, 120–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Guidelines, in Myalgic Encephalomyelitis (or Encephalopathy)/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome: Diagnosis and Management; National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE): London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Peo, L.-C.; Wiehler, K.; Paulick, J.; Gerrer, K.; Leone, A.; Viereck, A.; Haegele, M.; Stojanov, S.; Warlitz, C.; Augustin, S. Pediatric and adult patients with ME/CFS following COVID-19: A structured approach to diagnosis using the Munich Berlin Symptom Questionnaire (MBSQ). Eur. J. Pediatr. 2024, 183, 1265–1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jason, L.A.; Sunnquist, M. The development of the DePaul Symptom Questionnaire: Original, expanded, brief, and pediatric versions. Front. Pediatr. 2018, 6, 409729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goudsmit, E.M.; Nijs, J.; Jason, L.A.; Wallman, K.E. Pacing as a strategy to improve energy management in myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome: A consensus document. Disabil. Rehabil. 2012, 34, 1140–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grande, T.; Grande, B.; Gerner, P.; Hammer, S.; Stingl, M.; Vink, M.; Hughes, B.M. The role of psychotherapy in the Care of Patients with Myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome. Medicina 2023, 59, 719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolton, M.J.; Chapman, B.P.; Van Marwijk, H. Low-dose naltrexone as a treatment for chronic fatigue syndrome. BMJ Case Rep. CP 2020, 13, e232502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Kelly, B.; Vidal, L.; McHugh, T.; Woo, J.; Avramovic, G.; Lambert, J.S. Safety and efficacy of low dose naltrexone in a long covid cohort; an interventional pre-post study. Brain Behav. Immun.-Health 2022, 24, 100485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campagnolo, N.; Johnston, S.; Collatz, A.; Staines, D.; Marshall-Gradisnik, S. Dietary and nutrition interventions for the therapeutic treatment of chronic fatigue syndrome/myalgic encephalomyelitis: A systematic review. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 2017, 30, 247–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nisenbaum, R.; Jones, J.F.; Unger, E.R.; Reyes, M.; Reeves, W.C. A population-based study of the clinical course of chronic fatigue syndrome. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2003, 1, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Joustra, M.L.; Minovic, I.; Janssens, K.A.M.; Bakker, S.J.L.; Rosmalen, J.G.M. Vitamin and mineral status in chronic fatigue syndrome and fibromyalgia syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0176631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steiner, S.; Fehrer, A.; Hoheisel, F.; Schoening, S.; Aschenbrenner, A.; Babel, N.; Bellmann-Strobl, J.; Finke, C.; Fluge, Ø.; Froehlich, L.; et al. Understanding, diagnosing, and treating Myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome—State of the art: Report of the 2nd international meeting at the Charité Fatigue Center. Autoimmun Rev. 2023, 22, 103452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castro-Marrero, J.; Cordero, M.D.; Segundo, M.J.; Sáez-Francàs, N.; Calvo, N.; Román-Malo, L.; Aliste, L.; Fernández de Sevilla, T.; Alegre, J. Does oral Coenzyme Q10 Plus NADH Supplementation Improve Fatigue and Biochemical Parameters in Chronic Fatigue Syndrome? Mary Ann Liebert, Inc.:: New Rochelle, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Forsyth, L.M.; Preuss, H.G.; MacDowell, A.L.; Chiazze Jr, L.; Birkmayer, G.D.; Bellanti, J.A. Therapeutic effects of oral NADH on the symptoms of patients with chronic fatigue syndrome. Ann. Allergy Asthma Immunol. 1999, 82, 185–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armstrong, C.W.; McGregor, N.R.; Lewis, D.P.; Butt, H.L.; Gooley, P.R. Metabolic profiling reveals anomalous energy metabolism and oxidative stress pathways in chronic fatigue syndrome patients. Metabolomics 2015, 11, 1626–1639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giloteaux, L.; Goodrich, J.K.; Walters, W.A.; Levine, S.M.; Ley, R.E.; Hanson, M.R. Reduced diversity and altered composition of the gut microbiome in individuals with myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome. Microbiome 2016, 4, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- König, R.S.; Albrich, W.C.; Kahlert, C.R.; Bahr, L.S.; Löber, U.; Vernazza, P.; Scheibenbogen, C.; Forslund, S.K. The gut microbiome in myalgic encephalomyelitis (ME)/chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS). Front. Immunol. 2022, 12, 628741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, A.R.; Bernardo, A.; Costa, J.; Cardoso, A.; Santos, P.; de Mesquita, M.F.; Vaz Patto, J.; Moreira, P.; Silva, M.L.; Padrao, P. Dietary interventions in fibromyalgia: A systematic review. Ann. Med. 2019, 51 (Suppl. 1), 2–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chambers, D.; Bagnall, A.-M.; Hempel, S.; Forbes, C. Interventions for the treatment, management and rehabilitation of patients with chronic fatigue syndrome/myalgic encephalomyelitis: An updated systematic review. J. R. Soc. Med. 2006, 99, 506–520. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poenaru, S.; Abdallah, S.J.; Corrales-Medina, V.; Cowan, J. COVID-19 and post-infectious myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome: A narrative review. Ther. Adv. Infect. Dis. 2021, 8, 20499361211009385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Endnote Team. EndNote; Clarivate: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Sterne, J.A.; Savović, J.; Page, M.J.; Elbers, R.G.; Blencowe, N.S.; Boutron, I.; Cates, C.J.; Cheng, H.-Y.; Corbett, M.S.; Eldridge, S.M. RoB 2: A revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 2019, 366, l4898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sterne, J.A.; Hernán, M.A.; Reeves, B.C.; Savović, J.; Berkman, N.D.; Viswanathan, M.; Henry, D.; Altman, D.G.; Ansari, M.T.; Boutron, I.; et al. ROBINS-I: A tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. BMJ 2016, 355, i4919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, L.-L.; Wang, Y.-Y.; Yang, Z.-H.; Huang, D.; Weng, H.; Zeng, X.-T. Methodological quality (risk of bias) assessment tools for primary and secondary medical studies: What are they and which is better? Mil. Med. Res. 2020, 7, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGuinness, L.A.; Higgins, J.P.T. Risk-of-bias VISualization (robvis): An R package and Shiny web app for visualizing risk-of-bias assessments. Res. Synth. Methods 2021, 12, 55–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brouwers, F.; Van Der Werf, S.; Bleijenberg, G.; Van Der Zee, L.; Van Der Meer, J. The effect of a polynutrient supplement on fatigue and physical activity of patients with chronic fatigue syndrome: A double-blind randomized controlled trial. Qjm Int. J. Med. 2002, 95, 677–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castro-Marrero, J.; Segundo, M.J.; Lacasa, M.; Martinez-Martinez, A.; Sentañes, R.S.; Alegre-Martin, J. Effect of dietary coenzyme Q10 plus NADH supplementation on fatigue perception and health-related quality of life in individuals with myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome: A prospective, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukuda, S.; Nojima, J.; Kajimoto, O.; Yamaguti, K.; Nakatomi, Y.; Kuratsune, H.; Watanabe, Y. Ubiquinol-10 supplementation improves autonomic nervous function and cognitive function in chronic fatigue syndrome. Biofactors 2016, 42, 431–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lacasa, M.; Alegre-Martin, J.; Sentañes, R.S.; Varela-Sende, L.; Jurek, J.; Castro-Marrero, J. Yeast Beta-Glucan Supplementation with Multivitamins Attenuates Cognitive Impairments in Individuals with Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial. Nutrients 2023, 15, 4504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostojic, S.M.; Stojanovic, M.; Drid, P.; Hoffman, J.R.; Sekulic, D.; Zenic, N. Supplementation with Guanidinoacetic Acid in Women with Chronic Fatigue Syndrome. Nutrients 2016, 8, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bleijenberg, G.; van der Meer, J.W.M.; The GKH. The effect of acclydine in chronic fatigue syndrome: A randomized controlled trial. PLoS Clin. Trials 2007, 2, e19. [Google Scholar]

- Cash, A.; Kaufman, D.L. Oxaloacetate Treatment for Mental and Physical Fatigue in Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS) and Long-COVID fatigue patients: A non-randomized controlled clinical trial. J. Transl. Med. 2022, 20, 295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wearden, A.J.; Morriss, R.K.; Mullis, R.; Strickland, P.; Pearson, D.J.; Appleby, L.; Campbell, I.T.; Morris, J.A. Randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled treatment trial of fluoxetine and graded exercise for chronic fatigue syndrome. Br. J. Psychiatry 1998, 172, 485–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vermeulen, R.C.; Scholte, H.R. Exploratory open label, randomized study of acetyl-and propionylcarnitine in chronic fatigue syndrome. Psychosom. Med. 2004, 66, 276–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maric, D.; Brkic, S.; Mikic, A.N.; Tomic, S.; Cebovic, T.; Turkulov, V. Multivitamin mineral supplementation in patients with chronic fatigue syndrome. Med. Sci. Monit. Int. Med. J. Exp. Clin. Res. 2014, 20, 47. [Google Scholar]

- Castro-Marrero, J.; Domingo, J.C.; Cordobilla, B.; Ferrer, R.; Giralt, M.; Sanmartín-Sentañes, R.; Alegre-Martín, J. Does Coenzyme Q10 Plus Selenium Supplementation Ameliorate Clinical Outcomes by Modulating Oxidative Stress and Inflammation in Individuals with Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome? Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2022, 36, 729–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menon, R.; Cribb, L.; Murphy, J.; Ashton, M.M.; Oliver, G.; Dowling, N.; Turner, A.; Dean, O.; Berk, M.; Ng, C.H. Mitochondrial modifying nutrients in treating chronic fatigue syndrome: A 16-week open-label pilot study. Adv. Integr. Med. 2017, 4, 109–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venturini, L.; Bacchi, S.; Capelli, E.; Lorusso, L.; Ricevuti, G.; Cusa, C. Modification of Immunological Parameters, Oxidative Stress Markers, Mood Symptoms, and Well-Being Status in CFS Patients after Probiotic Intake: Observations from a Pilot Study. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2019, 2019, 1684198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molenberghs, G.; Kenward, M. Missing Data in Clinical Studies; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Tripepi, G.; Jager, K.J.; Dekker, F.W.; Zoccali, C. Selection bias and information bias in clinical research. Nephron Clin. Pract. 2010, 115, c94–c99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skelly, A.C.; Dettori, J.R.; Brodt, E.D. Assessing bias: The importance of considering confounding. Evid.-Based Spine-Care J. 2012, 3, 9–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jackson, C. The Chalder fatigue scale (CFQ 11). Occup. Med. 2015, 65, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frith, J.; Newton, J. Fatigue impact scale. Occup. Med. 2010, 60, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vercoulen, J.H.; Swanick, C.; Fennis, J.F.; Galama, J.; Van Der Meer, J.W.; Bleijenber, G. Dimensional assessment of chronic fatigue syndrome. J. Psychosom. Res. 1994, 38, 383–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worm-Smeitink, M.; Gielissen, M.; Bloot, L.; van Laarhoven, H.W.M.; van Engelen, B.G.M.; van Riel, P.; Bleijenberg, G.; Nikolaus, S.; Knoop, H. The assessment of fatigue: Psychometric qualities and norms for the Checklist individual strength. J. Psychosom. Res. 2017, 98, 40–46. [Google Scholar]

- Cella, D.; Yount, S.; Rothrock, N.; Gershon, R.; Cook, K.; Reeve, B.; Ader, D.; Fries, J.F.; Bruce, B.; Rose, M. The Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS): Progress of an NIH Roadmap cooperative group during its first two years. Med. Care 2007, 45, S3–S11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zachrisson, O.; Regland, B.; Jahreskog, M.; Kron, M.; Gottfries, C.G. A rating scale for fibromyalgia and chronic fatigue syndrome (the FibroFatigue scale). J. Psychosom. Res. 2002, 52, 501–509. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Smets, E.; Garssen, B.; Bonke, B.d.; De Haes, J. The Multidimensional Fatigue Inventory (MFI) psychometric qualities of an instrument to assess fatigue. J. Psychosom. Res. 1995, 39, 315–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ware, J.E.; Snow, K.K.; Kosinski, M.; Gandek, B. SF-36 health survey. Man. Interpret. Guide 1993, 2, 1–316. [Google Scholar]

- Buysse, D.J.; Reynolds, C.F.; Monk, T.H.; Berman, S.R.; Kupfer, D.J. The Pittsburgh sleep quality index: A new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res. 1989, 28, 193–213. [Google Scholar]

- Bastien, C.H.; Vallières, A.; Morin, C.M. Validation of the Insomnia Severity Index as an outcome measure for insomnia research. Sleep Med. 2001, 2, 297–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beck, A.T.; Steer, R.A.; Carbin, M.G. Psychometric properties of the Beck Depression Inventory: Twenty-five years of evaluation. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 1988, 8, 77–100. [Google Scholar]

- Beck, A.T.; Ward, C.H.; Mendelson, M.; Mock, J.; Erbaugh, J. An inventory for measuring depression. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 1961, 4, 561–571. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Radloff, L.S. The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl. Psychol. Meas. 1977, 1, 385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery, S.; Asberg, M. MADRS scale. Br. J. Psychiatry 1979, 134, 382–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bergner, M.; Bobbitt, R.A.; Carter, W.B.; Gilson, B.S. The Sickness Impact Profile: Development and Final Revision of a Health Status Measure. Med. Care 1981, 19, 787–805. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Jones, R.M.; Patel, K.; Moscovici, M.; McMaster, R.; Glancy, G.; Simpson, A.I. Adaptation of the clinical global impression for use in correctional settings: The CGI-C. Front. Psychiatry 2019, 10, 687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stroop, J.R. Studies of interference in serial verbal reactions. J. Exp. Psychol. 1935, 18, 643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Kloot, W.A.; Oostendorp, R.A.; van der Meij, J.; van den Heuvel, J. The Dutch version of the McGill pain questionnaire: A reliable pain questionnaire. Ned. Tijdschr. Voor Geneeskd. 1995, 139, 669–673. [Google Scholar]

- Ware, J.E.; Kosinski, M.; Keller, S.D. A 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey: Construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med. Care 1996, 34, 220–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guy, W. ECDEU Assessment Manual for Psychopharmacology; US Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, Public Health Service: Washington, DC, USA, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Mundt, J.C.; Marks, I.M.; Shear, M.K.; Greist, J.M. The Work and Social Adjustment Scale: A simple measure of impairment in functioning. Br. J. Psychiatry 2002, 180, 461–464. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Altmann, D.M.; Whettlock, E.M.; Liu, S.; Arachchillage, D.J.; Boyton, R.J. The immunology of long COVID. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2023, 23, 618–634. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Davis, H.E.; McCorkell, L.; Vogel, J.M.; Topol, E.J. Long COVID: Major findings, mechanisms and recommendations. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2023, 21, 133–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bansal, A.S. Investigating unexplained fatigue in general practice with a particular focus on CFS/ME. BMC Fam. Pract. 2016, 17, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caswell, A.; Daniels, J. Anxiety and Depression in Chronic Fatigue Syndrome: Prevalence and Effect on Treatment. A Systematic Review, Meta-Analysis and Meta-Regression; British Association of Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy: Glasgow, UK, 2018; pp. 18–20. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Reyes, I.; Chandel, N.S. Mitochondrial TCA cycle metabolites control physiology and disease. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 102. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Holden, S.; Maksoud, R.; Eaton-Fitch, N.; Cabanas, H.; Staines, D.; Marshall-Gradisnik, S. A systematic review of mitochondrial abnormalities in myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome/systemic exertion intolerance disease. J. Transl. Med. 2020, 18, 290. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Morten, K.J.; Davis, L.; Lodge, T.A.; Strong, J.; Espejo-Oltra, J.A.; Zalewski, P.; Pretorius, E. Altered Lipid, Energy Metabolism and Oxidative Stress Are Common Features in a Range of Chronic Conditions. Heliyon 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Booth, N.E.; Myhill, S.; McLaren-Howard, J. Mitochondrial dysfunction and the pathophysiology of myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS). Int. J. Clin. Exp. Med. 2012, 5, 208. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Billing-Ross, P.; Germain, A.; Ye, K.; Keinan, A.; Gu, Z.; Hanson, M.R. Mitochondrial DNA variants correlate with symptoms in myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome. J. Transl. Med. 2016, 14, 19. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Niyazov, D.M.; Kahler, S.G.; Frye, R.E. Primary Mitochondrial Disease and Secondary Mitochondrial Dysfunction: Importance of Distinction for Diagnosis and Treatment. Mol. Syndromol. 2016, 7, 122–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billing-Ross, P.; Germain, A.; Ye, K.; Keinan, A.; Gu, Z.; Hanson, M.R. Coenzyme Q10 deficiency in myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS) is related to fatigue, autonomic and neurocognitive symptoms and is another risk factor explaining the early mortality in ME/CFS due to cardiovascular disorder. Neuro Endocrinol. Lett. 2009, 30, 470–476. [Google Scholar]

- Mantle, D. and A. Dybring, Bioavailability of Coenzyme Q10: An Overview of the Absorption Process and Subsequent Metabolism. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 386. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Schmelzer, C.; Lindner, I.; Rimbach, G.; Niklowitz, P.; Menke, T.; Döring, F. Functions of coenzyme Q10 in inflammation and gene expression. Biofactors 2008, 32, 179–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicolson, G.L.; Ash, M.E. Lipid Replacement Therapy: A natural medicine approach to replacing damaged lipids in cellular membranes and organelles and restoring function. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)—Biomembr. 2014, 1838, 1657–1679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, F.; Roh, Y.S. Mitochondrial connection to ginsenosides. Arch. Pharmacal Res. 2020, 43, 1031–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ostojic, S.M.; Jorga, J. Guanidinoacetic acid in human nutrition: Beyond creatine synthesis. Food Sci. Nutr. 2023, 11, 1606–1611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nogueira, L.; Hogan, D.; Hogan, M.C. Acute Oxaloacetate Exposure Enhances Resistance to Fatigue in in vitro Mouse Soleus Muscle. FASEB J. 2011, 25, 1104.5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Germain, A.; Ruppert, D.; Levine, S.M.; Hanson, M.R. Metabolic profiling of a myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome discovery cohort reveals disturbances in fatty acid and lipid metabolism. Mol. Biosyst. 2017, 13, 371–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnston, S.C.; Staines, D.R.; Marshall-Gradisnik, S.M. Epidemiological characteristics of chronic fatigue syndrome/myalgic encephalomyelitis in Australian patients. Clin. Epidemiol. 2016, 8, 97–107. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Nagy-Szakal, D.; Williams, B.L.; Mishra, N.; Che, X.; Lee, B.; Bateman, L.; Klimas, N.G.; Komaroff, A.L.; Levine, S.; Montoya, J.G.; et al. Fecal metagenomic profiles in subgroups of patients with myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome. Microbiome 2017, 5, 44. [Google Scholar]

- Xiong, R.; Gunter, C.; Fleming, E.; Vernon, S.D.; Bateman, L.; Unutmaz, D.; Oh, J. Multi-‘omics of gut microbiome-host interactions in short- and long-term myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome patients. Cell Host Microbe 2023, 31, 273–287.e5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Colletti, A.; Pellizzato, M.; Cicero, A.F. The Possible Role of Probiotic Supplementation in Inflammation: A Narrative Review. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 2160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hill, C.; Guarner, F.; Reid, G.; Gibson, G.R.; Merenstein, D.J.; Pot, B.; Morelli, L.; Canani, R.B.; Flint, H.J.; Salminen, S.; et al. The International Scientific Association for Probiotics and Prebiotics consensus statement on the scope and appropriate use of the term probiotic. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2014, 11, 506–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grabowska, A.D.; Westermeier, F.; Nacul, L.; Lacerda, E.; Sepúlveda, N. The importance of estimating prevalence of ME/CFS in future epidemiological studies of long COVID. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1275827. [Google Scholar]

- de Bles, N.J.; Gast, D.A.A.; van der Slot, A.J.C.; Didden, R.; van Hemert, A.M.; Rius-Ottenheim, N.; Giltay, E.J. Lessons learned from two clinical trials on nutritional supplements to reduce aggressive behaviour. J. Eval. Clin. Pract. 2022, 28, 607–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mirmiran, P.; Bahadoran, Z.; Gaeini, Z. Common Limitations and Challenges of Dietary Clinical Trials for Translation into Clinical Practices. Int. J. Endocrinol. Metab. 2021, 19, e108170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bacchetti, P. Current sample size conventions: Flaws, harms, and alternatives. BMC Med. 2010, 8, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pendergrast, T.; Brown, A.; Sunnquist, M.; Jantke, R.; Newton, J.L.; Strand, E.B.; Jason, L.A. Housebound versus nonhousebound patients with myalgic encephalomyelitis and chronic fatigue syndrome. Chronic Illn. 2016, 12, 292–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sedgwick, P. Bias in observational study designs: Prospective cohort studies. BMJ 2014, 349, g7731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Falk Hvidberg, M.; Brinth, L.S.; Olesen, A.V.; Petersen, K.D.; Ehlers, L. The Health-Related Quality of Life for Patients with Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS). PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0132421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lenz, C.; Slack, M.P.; Shea, K.M.; Reinert, R.R.; Taysi, B.N.; Swerdlow, D.L. Long-Term effects of COVID-19: A review of current perspectives and mechanistic insights. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 2024, 50, 315–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komaroff, A.L.; Lipkin, W.I. ME/CFS and Long COVID share similar symptoms and biological abnormalities: Road map to the literature. Front. Med. 2023, 10, 1187163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro-Marrero, J.; Faro, M.; Aliste, L.; Sáez-Francàs, N.; Calvo, N.; Martínez-Martínez, A.; de Sevilla, T.F.; Alegre, J. Comorbidity in Chronic Fatigue Syndrome/Myalgic Encephalomyelitis: A Nationwide Population-Based Cohort Study. Psychosomatics 2017, 58, 533–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruiz, E.; Alegre, J.; AMGQ; Aliste, L.; Blázquez, A.; Fernández de Sevilla, T. Chronic fatigue syndrome: Study of a consecutive series of 824 cases assessed in two specialized units. Rev. Clin. Esp. 2011, 211, 385–390. [Google Scholar]

- Momen, N.C.; Østergaard, S.D.; Heide-Jorgensen, U.; Sørensen, H.T.; McGrath, J.J.; Plana-Ripoll, O. Associations between physical diseases and subsequent mental disorders: A longitudinal study in a population-based cohort. World Psychiatry 2024, 23, 421–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Engelsen, J.; Nielsen, J.D.; Winther, K. Effect of coenzyme Q10 and Ginkgo biloba on warfarin dosage in stable, long-term warfarin treated outpatients. A randomised, double blind, placebo-crossover trial. Thromb. Haemost. 2002, 87, 1075–1076. [Google Scholar]

- Eikelboom, J.W.; Weitz, J.I. New anticoagulants. Circulation 2010, 121, 1523–1532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsai, H.H.; Lin, H.W.; Simon Pickard, A.; Tsai, H.Y.; Mahady, G. Evaluation of documented drug interactions and contraindications associated with herbs and dietary supplements: A systematic literature review. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 2012, 66, 1056–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ho, M.J.; Bellusci, A.; Wright, J.M. Blood Pressure Lowering Efficacy of Coenzyme Q10 for Primary Hypertension. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2009, 3, CD007435. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg, D.M.; Kessler, R.C.; Van Rompay, M.I.; Kaptchuk, T.J.; Wilkey, S.A.; Appel, S.; Davis, R.B. Perceptions about complementary therapies relative to conventional therapies among adults who use both: Results from a national survey. Ann. Intern. Med. 2001, 135, 344–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jason, L.A.; Sunnquist, M.; Brown, A.; Reed, J. Defining Essential Features of Myalgic Encephalomyelitis and Chronic Fatigue Syndrome. J. Hum. Behav. Soc. Environ. 2015, 25, 657–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strand, E.B.; Nacul, L.; Mengshoel, A.M.; Helland, I.B.; Grabowski, P.; Krumina, A.; Alegre-Martin, J.; Efrim-Budisteanu, M.; Sekulic, S.; Pheby, D. Myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS): Investigating care practices pointed out to disparities in diagnosis and treatment across European Union. PLoS ONE. 2019, 14, e0225995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michielsen, H.J.; De Vries, J.; Van Heck, G.L. Psychometric qualities of a brief self-rated fatigue measure: The Fatigue Assessment Scale. J. Psychosom. Res. 2003, 54, 345–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krogsgaard, M.R.; Brodersen, J.; Christensen, K.B.; Siersma, V.; Kreiner, S.; Jensen, J.; Hansen, C.F.; Comins, J.D. What is a PROM and why do we need it? Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2021, 31, 967–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Churruca, K.; Pomare, C.; Ellis, L.A.; Long, J.C.; Henderson, S.B.; Murphy, L.E.D.; Leahy, C.J.; Braithwaite, J. Patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs): A review of generic and condition-specific measures and a discussion of trends and issues. Health Expect 2021, 24, 1015–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kluzek, S.; Dean, B.; Wartolowska, K.A. Patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) as proof of treatment efficacy. BMJ Evid. Based Med. 2022, 27, 153–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Królikowska, A.; Reichert, P.; Senorski, E.H.; Karlsson, J.; Becker, R.; Prill, R. Scores and sores: Exploring patient-reported outcomes for knee evaluation in orthopaedics, sports medicine and rehabilitation. Knee Surg. Sports Traumatol. Arthrosc. 2024, 31, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brookhart, M.A.; Stürmer, T.; Glynn, R.J.; Rassen, J.; Schneeweiss, S. Confounding control in healthcare database research: Challenges and potential approaches. Med. Care 2010, 48, S114–S120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harvey, R.D.; Mileham, K.F.; Bhatnagar, V.; Brewer, J.R.; Rahman, A.; Moravek, C.; Kennedy, A.S.; Ness, E.A.; Dees, E.C.; Ivy, S.P.; et al. Modernizing Clinical Trial Eligibility Criteria: Recommendations of the ASCO-Friends of Cancer Research Washout Period and Concomitant Medication Work Group. Clin. Cancer Res. 2021, 27, 2400–2407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mettler, S.; Zimmermann, M.B. Iron excess in recreational marathon runners. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2010, 64, 490–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ronis, M.J.; Pedersen, K.B.; Watt, J. Adverse effects of nutraceuticals and dietary supplements. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2018, 58, 583–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reid, M.E.; Stratton, M.S.; Lillico, A.J.; Fakih, M.; Natarajan, R.; Clark, L.C.; Marshall, J.R. A report of high-dose selenium supplementation: Response and toxicities. J. Trace Elem. Med. Biol. 2004, 18, 69–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lordan, R. Dietary supplements and nutraceuticals market growth during the coronavirus pandemic—Implications for consumers and regulatory oversight. PharmaNutrition 2021, 18, 100282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Inclusion | Exclusion |

|---|---|

| Studies conducted on humans, regardless of age and gender/sex; studies including participants diagnosed with ME/CFS based on current diagnostic criteria (Fukuda, International Consensus Criteria ICC, Revised Canadian Consensus Criteria CCC, Institute of Medicine Report IOM, NICE Guidelines NG206 [18,19,20,21,22]) | Animal studies; studies including participants diagnosed with ME/CFS based on other criteria or patients not even diagnosed with ME/CFS |

| Studies assessing the efficacy of DSs (multi- or single-DS products) | Studies that used multi-treatments (e.g., DSs and cognitive behavioral therapy or pharmacotherapy) |

| Studies including no control group or control groups of healthy controls | Studies that explicitly compared other patient groups (e.g., depression, multiple sclerosis) with ME/CFS patients |

| Studies assessing the efficacy of DSs on fatigue symptoms in ME/CFS as outcome variable | Studies that used other primary outcome variables than fatigue |

| Intervention studies (RCTs, clinical trials, …); studies conducted and published from 1994 to the present to exclude studies conducted before the CDC Fukuda criteria [18] were published; studies available in full text; studies available in English; studies reporting original research | Non-interventional studies; studies conducted and published before 1994; studies not available in full text (even on request); studies not available in English; reviews, case reports, study protocols, duplicates |

| Sample (n) | Mean Age (SD) in Years | Sex, Female % | Mean Illness Duration (SD) (years) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Authors | Treat (n) | Cont (n) | Treat | Cont | Treat | Cont | Treat | Cont |

| Brouwers et al., 2002 [47] | 27 | 26 | 40 (9.9) | 38.9 (10.9) | 74 | 65 | 8 (NR) | 4.5 (NR) |

| Lacasa et al., 2023 [50] | 29 | 22 | 52.9 (6.5) | 52.5 (7.5) | 100 | 100 | NR | NR |

| Maric et al., 2014 [56] | 36 | NA | NR (18–50) | NA | 36 | NA | NR | NA |

| Menon et al., 2017 [58] | 10 | NA | 36.3 (10.5) | NA | 70 | NA | 11 (7.04) | NA |

| Venturini et al., 2019 [59] | 9 | NA | NR | NA | NR | NA | NR | NA |

| Castro-Marrero et al., 2022 [57] | 35 | NA | 47.3 (1.5) | NA | 100 | NA | NR | NA |

| Castro-Marrero et al., 2021 [48] | 72 | 72 | 45.4 (7.8) | 46.8 (6.5) | 100 | 100 | 15.4 (8.9) | 14.7 (6.2) |

| Castro-Marrero et al., 2015 [33] | 39 | 34 | 49.3 (7.1) | NR | 100 | 100 | 15.4 (8.9) | 14.7 (6.2) |

| Forsythe et al., 1999 [34] | 26 | 26 | 39.6 (NR) | 39,6 | 65 | 65 | 7.2 (NR) | 7.2 |

| Fukuda et al., 2016 (PIL) [49] | 20 | NA | 36.9 (6.9) | NA | 75 | NA | 10.3 (5.4) | NA |

| Fukuda et al., 2016 (RCT) [49] | 17 | 14 | 34.8 (9.4) | 39.5 (8.5) | 77 | 86 | NR | NR |

| Ostojic et al., 2016 [51] | 21 | 21 | 39.3 (8.8) | 39.3 (8.8) | 100 | 100 | NR | NR |

| Vermeulen et al., 2004 [55] | 89 (ALC = 29; PLC = 30; ALCPLC = 30) | NA | ALC: 37 (11); PLC: 38 (11); ALCPLC: 42 (12) | NA | 78 | NA | ALC: 5.5 (NR); PLC: 3 (NR); ALCPLC: 6.0 (NR) | NA |

| The et al., 2007 [52] | 22 | 22 | 40.9 (9.4) | 43.4 (11.2) | 82 | 82 | NR | NA |

| Cash and Kaufmann, 2022 [53] | 76 (A = 23; B = 29; C = 24) | 29 | 47 (NR) | NR | 74 | NR | 8.9 (NR) | NR |

| Intervention | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Authors | Country | Study Design | ME/CFS Diagn Tool | Treat | Cont | Study Time # | Treat Time # | Washout Time # |

| Brouwers et al., 2002 [47] | NLD | RCT | FUK | Multi-supplement (vitamins, minerals, (co)enzymes; Numico Research BV, The Hague, The Netherlands); BID | Identical placebo, no active ingredients | 12 | 10 | NA |

| Lacasa et al., 2023 [50] | Spain | RCT | FUK | ImmunoVita® (Vitae Health Innovation S.L., Barcelona, Spain); four capsules/d, empty stomach, 30 min. before breakfast and dinner, only with water | Identical placebo, no active ingredients | 36 | 36 | NA |

| Maric et al., 2014 [56] | Serbia | EXP OL SA | FUK | Supradyn® (Bayer Schering Pharma, Beograd, Serbia) | None | 8 | 8 | NA |

| Menon et al., 2017 [58] | AUS | OL PIL | FUK | Multi-supplement (CoQ10 200 mg; ALA 150 mg; NAC 2000 mg; ALC 1000 mg; Mag 64 mg; Vit C 240 mg; Vit D3 12.5 µg; Vit E 60 IU; Vit A 900 µgREIU; vit B co-factors (B7 600 µg, B1 hydrochloride 100 mg, B2 100 mg, B3 200 mg, B5 100 mg, B6 hydrocholoride 100 mg, B9 800 mg, B12 800 mg); BioCeuticals1, Surry Hills, Australia); one tablet BID | None | 16 | 16 | NA |

| Venturini et al., 2019 [59] | Italy | PIL | FUK | Enterelle, Bifiselle, Rotanelle, Citogenex, Ramnoselle (all from Bromatech s.r.l., Milan, Italy); week 1: Enterelle 2 cps bid; week 2: Bifiselle 2 cps bid; week 3: Ramnoselle 2 cps bid + Enterelle 2 cps; week 4–8: Citogenex 2 cps + Rotanelle 2 cps | None | 8 | 8 | NA |

| Castro-Marrero et al., 2022 [57] | Spain | PIL SA OL | FUK | Bio-Quinone Active (100 mg CoQ10; Pharma Nord, Vejle, Denmark) + Seleno Precise (200 g organic selenium yeast; Pharma Nord, Vejle, Denmark); 4/d soft gel capsules CoQ10 + 1/d tablet selenium | NA | 8 | 8 | NA |

| Castro-Marrero et al., 2021 [48] | Spain | RCT | FUK | Combination supplement (200 mg of CoQ10 + 20 mg of NADH) + excipient (20 mg phosphatidylserine + 40 mg Vit C) four tablets/daily | Excipient (20 mg phosphatidylserine + 40 mg vit C) | 12 | 8 | 4 |

| Castro-Marrero et al., 2015 [33] | Spain | RCT | FUK | Soft gel capsules (100 mg oral CoQ10 + 10 mg NADH; Vitae Natural Nutrition S.L., Barcelona, Spain)BID | Identical placebo with no active ingredients | 8 | 8 | NA |

| Forsythe et al., 1999 [34] | USA | RCT CO | FUK | ENADA (10 mg NADH), two 5 mg tablets daily, orally, 1/day (45 min before breakfast on an empty stomach with a glass of water) | Equivalent placebo, two 5 mg tablet formulation | 12 | 8 (4 cont + 4 treat) | 4 |

| Fukuda et al., 2016 [49] | Japan | OL PIL | FUK | Soft gel capsules (50 mg of CoQ10; Kaneka, Tokyo, Japan) TID (150 mg total), after meals | None | 8 | 8 | 2 |

| Fukuda et al., 2016 [49] | Japan | RA PC PA | FUK | Soft gel capsules (50 mg of CoQ10; Kaneka) TID (150 mg total), after meals | Identical placebo with no active ingredients | 12 | 12 | NA |

| Ostojic et al., 2016 [51] | Serbia | RCT CO | FUK | GAA (2.4 g per day), oral administration | Identical cellulose placebo, no active ingredients | 32 | 24 (12 placebo + 12 treat) | 8 (in between trials) |

| Vermeulen et al., 2004 [55] | NLD | EXP OL RA | FUK | 2 g/d acetyl-L-carnitine OR 2 g/d propionyl-L-carnitine OR 2 g/d acetyl-L-carnitine + 2 g/d propionyl-L-carnitine | None | 34 | 24 | 2 weeks |

| The et al., 2007 [52] | NLD | RCT | FUK | Acclydine (250 mg; Optipharma, Susteren, The Netherlands) + amino acid supplements; week 1–2, 1000 mg/d; week 3–6, 750 mg/d; week 7–8, 500 mg/d; week 9–10, 500 mg every 2 d; week 11–12, 250 mg/d; week 13–14, 250 mg every 2 d | Identical placebo, no active ingredients | 14 | 14 | NA |

| Cash and Kaufmann, 2022 [53] | USA | NRCT | FUK | AEO (A: 500 mg AEO BID; B: 1000 mg AEO BID; C: 1000 mg AEO TID) | Historical oral placebo | 6 | 6 | NA |

| Authors | Outcome Measures | Results |

| Multi-Supplements | ||

| Brouwers et al., 2002 [47] | CIS-D FUK CODI and DOF | No significant treatment effects for self-report or behavioral measures. No significant differences between treat and cont for primary outcome measures. No change in complaints and no compete recovery at follow-up (x2 = 2, df (1,2), p = 0.36). |

| Lacasa et al., 2023 [50] | FIS-40 | Significant improvement in the cognitive domain from baseline at the 36-week visit in the intervention group (p = 0.03). FIS-40 domain scores evolved in parallel between groups over the course of the study. |

| Maric et al., 2014 [56] | FFS | No significant change in total FFS score after treatment (p > 0.05). Significant decreases in fatigue (p < 0.0001), sleep disorders (p = 0.008), autonomic nervous system symptoms (p = 0.02), frequency and intensity of headaches (p < 0.0001), and subjective feeling of infection (p = 0.0002). |

| Menon et al., 2017 [58] | CFQ | Significant reduction of mean total CFQ scores (F(4,29) = 6.31, p < 0.001). Most notable reduction between baseline and week four (mean difference 7.66, p < 0.01). Nine out of eleven CFQ items improved (p < 0.05), with a 55% reduction in the severity of “need for more rest” (p < 0.01), but there were no significant improvements in “memory” and “problems starting things” (p > 0.05). |

| Probiotics | ||

| Venturini et al., 2019 [59] | CFQ | Progressive reduction of CFQ. |

| Coenzymes | ||

| Castro-Marrero et al., 2022 [57] | FIS-40 | Statistically significant differences in the scores for perceived overall fatigue (p = 0.02). Statistically significant improvement of physical (p = 0.007) and cognitive fatigue perception (p = 0.04) at the end of intervention. |

| Castro-Marrero et al., 2021 [48] | FIS-40 | Significant improvement of cognitive fatigue perception for treat at week four and eight from baseline (p = 0.005 and p = 0.01, respectively). Nominal improvement in the psychosocial domain for treat at week four, but no statistical significance (p = 0.05). Significant decrease of total FIS-40 scores at week four from baseline (p = 0.02), but no significant change at follow-up (p = 0.09 and p = 0.07, respectively). FIS-40 domain scores evolved in parallel between groups over the course of the study. |

| Castro-Marrero et al., 2015 [33] | FIS-40 | Significant improvement of fatigue after eight weeks: reduction in FIS-40 total score (p < 0.05). |

| Forsythe et al., 1999 [34] | Symptom scoring system based on FUK | Present in all patients were fatigue, neurocognitive difficulties, and sleep disturbances. High-frequency symptomatology was PEM, headache, and muscle weakness; remainder had decreasing frequency of myalgias, arthralgias, and lymphadenopathy. Success rate for TREAT was 31% vs. 8% CONT (p = 0.05). In total, 35% of subjects were able to correctly evaluate the NADH-treatment period; 72% of study patients reported significant improvement in clinical symptomatology and energy levels at follow-up. |

| Fukuda et al., 2016 [49] | CFQ | PIL: no significant differences before and after treatment (p > 0.05). RCT: no significant differences of subjective fatigue symptoms between treat and cont (p > 0.05). Changes in these symptoms dependent on CoQ10 increase and OSI decrease in CFS patients after intervention. |

| Amino acids | ||

| Ostojic et al., 2016 [51] | MFI-20 | No effects of the intervention for general fatigue or physical fatigue (p > 0.05). GAA attenuated other aspects of fatigue, such as activity, motivation, and mental fatigue (p < 0.05). |

| Vermeulen et al., 2004 [55] | MFI-20 | Significant improvement of general fatigue score for PLC (p = 0.004) and ALCPLC (p < 0.001). Significant improvement of mental fatigue for ALC (p = 0.02). |

| Other | ||

| The et al., 2007 [52] | CIS-F CODI + DOF | No significant differences in change scores between treat and cont (p > 0.05). No significant decrease in treat for fatigue severity (CIS-fatigue +1.1 [95% CI −4.4 to +6.5, p = 0.7]) or functional impairment (SIP-8 +59.1 [95% CI −201.7 to +319.8, p = 0.65]) compared to CONT. No significant differences for fatigue severity (DOF; p > 0.05). |

| Cash and Kaufmann, 2022 [53] | CFQ FSS PROMIS-SF-7a | Reduction of measurable fatigue to score 4 or less in 22% of all patients. Drop to 4 or less on CFQ in 28% of patients in 1000 mg AEO BID treatment group and 33% of patients with 1000 mg AEO TID. Compared to historical placebo, 75% of ME/CFS participants reported an improvement in fatigue. |

| Authors | Secondary Outcome Measures | Secondary Outcome Results |

|---|---|---|

| PROMs | ||

| Brouwers et al., 2002 [47] | FUI: SIP8 | No significant differences between treat and cont for overall functional impairment (SIP8 = 182; 95% CI = −165 to 529, p = 0.3). |

| Lacasa et al., 2023 [50] | SQ: PSQI, DEP: HADS, HR-QOL: SF-36 | SQ: significant improvement of daytime dysfunction for treat (p = 0.01, with respect to the baseline) compared to cont. Other PSQI domain scores evolved in parallel over the course of the study. DEP: no significant differences between groups over the course of the study (p > 0.05). HR-QOL: social role functioning improved significantly compared to the baseline for cont (p = 0.01). A slight reduction in cognitive fatigue symptoms was reported, along with an improvement in self-reported HR-QoL for treat. SF-36 domain scores evolved in parallel between groups over the course of the study. |

| Maric et al., 2014 [56] | HR-QOL: SF-36 | At baseline and after treatment, no difference of HR-QOL between treat and the general population (p = 0.23 and p = 0.25, respectively). No influence of treat for HR-QOL (p > 0.05). CFS diagnosis alone affected diminished vitality (MD = 49.7 at both time points). Significant decreases in fatigue (p = 0.0009), sleep disorders (p = 0.008), autonomic nervous system symptoms (p = 0.02), frequency and intensity of headaches (p = 0.0001), and subjective feeling of infection (p = 0.0002). |

| The et al., 2007 [52] | FUI: SIP-8 | Significant decrease in treat (SIP-8 = +59.1 [95% CI −201.7 to +319.8, p = 0.65]) compared to cont. |

| Venturini et al., 2019 [59] | HR-QOL: SF-36 DEP: BDI-I and II | HR-QOL: progressive increase of both MCS and PCS. DEP: reduction of indexes during and after probiotic protocol in comparison with the basal values. |

| Castro-Marrero et al., 2022 [57] | HR-QOL: SF-36 SQ: PSQI | HR-QOL: significant improvements at week eight of intervention (p = 0.002). Bodily pain (p = 0.02), emotional role functioning (p = 0.02), and mental health domains (p = 0.05) improved from baseline. SQ: no significant differences (p > 0.05). |

| Castro-Marrero et al., 2021 [48] | SQ: PSQI HR-QOL: SF-36 | SQ: significant differences between treat and cont at 4-week follow-up from baseline (p = 0.02). Statistically significant differences for PSQI domains for treat from baseline over time (p < 0.05 for all). HR-QOL: physical role functioning, general health perception, vitality, social role functioning, emotional role functioning, and mental health status domains did not show any differences between treat and cont. Significant improvements in physical functioning for treat at both visits from baseline during treatment (p = 0.04 and p = 0.001, respectively). Significant improvement of bodily pain domain for treat at 4-week visit from baseline (p = 0.04). Reduction in vitality for cont at four-week follow-up (p = 0.04). |

| Vermeulen et al., 2004 [55] | CGI Stroop test MPQ-DLV | CGI: improvement; 59% ALC; 63% PLC; 37% ALCPLC; deterioration: 10% ALC; 3% PLC; 16% ALCPLC. Follow-Up: deterioration; 52% ALC; 50% PLC; 37% ALCPLC. No patients improved. COG: significant improvement in all groups. PAI: no significant change in any group (p > 0.05). Correlations of CGI improvement with MFI-20 improvement in all groups (r = 0.36, p = 0.05) and with Stroop in the ALC (r = 0.48, p = 0.01) and the ALCPLC (r = 0.49, p = 0.006), but not in the PLC group (p > 0.05). No correlation of CGI with PAI in any of the groups. |

| Ostojic et al., 2016 [51] | SF-36 PAI: VAS | Significant treatment vs. time interaction for HR-QOL (SF-36; p < 0.05). SF-36: significant improvement of both PCS and MCS for treat compared to cont (p < 0.05). PAI: no significant difference in musculoskeletal soreness over time between treat and cont (p > 0.05). |

| Fukuda et al., 2016 [49] | CES-D | PIL: significant improvements for treat, dependent on the increases in total plasma CoQ10 levels. No clinical outcomes changed over the course of the 8-week supplementation. RCT: no significant difference in depression between treat and cont (p > 0.05). |

| Menon et al., 2017 [58] | MADRS SF-12 CGI PGI WSAS SQ: ISI | DEP: no significant changes over time (F(4,32) = 1.5, p = 0.23). SF-12: no significant changes on the individual levels over time (p > 0.05). CGI: significant improvement (F(3,24), p = 0.01); CGI-S: no significant changes over time (F(4,33) = 1.81, p = 0.15). PGI: no significant changes over time (F(3,22) = 1.62, p = 0.33). WSAS: no significant changes over time (F(4,26) = 2.21, p = 0.1); SQ: significant improvement (F(4,32) = 3.55, p = 0.02). |

| Physiological parameters | ||

| Brouwers et al., 2002 [47] | EP: AGA | No significant differences between treat and cont (p > 0.05). |

| The et al., 2007 [52] | EP: AGA | No significant differences between groups (p > 0.05). |

| Ostojic et al., 2016 [51] | EP: AGA; isometric dynamometer; treadmill; breath-by-breath metabolic system; HR monitor | Significant differences in total quadriceps isometric strength and maximal oxygen uptake between the interventions (p < 0.05): No differences for daily energy expenditure (p = 0.98), physical activity duration (p = 0.23), and intensity (p = 0.22). Trend (p = 0.08) towards a difference in maximal workload during ergometry between groups. |

| Fukuda et al., 2016 [49] | UKPT; Life Scope; HRV and beat-to-beat variation | PIL: no clinical outcomes changed over the course of the supplementation (p > 0.05). RCT: UKPT: Significantly improved performance for treat compared to cont (p < 0.05). Life Scope: significant decrease of nighttime awakenings (>1 min and 5 min) for treat compared to cont. HRV and beat-to-beat variation: significant decrease in HF power for cont but not for treat |

| Laboratory parameters | ||

| Maric et al., 2014 [56] | Antioxidant status, SOD activity | SOD activity: significant correlations after treatment between SOD activity and physical aspect of HR-QOL: physical function (r = 0.33, p = 0.05), physical role (r = 0.37, p = 0.03), bodily pain (r = 0.43, p = 0.01), and total score (r = 0.39, p = 0.02). SOD and some HR-QOL mental aspects correlated after treatment: vitality (r = 0.37, p = 0.03), mental health (r = 0.41, p = 0.01), and total score (r = 0.43, p = 0.01). |

| Venturini et al., 2019 [59] | ESR; reactive oxygen metabolites; immunophenotyping of leukocytes; serum IgG, IgM, IgA, and IgE concentrations; UC; DHEA-S; CAL; CRP | Increase in UC (2.3×), ESR (1.7×), and DHEA-S (1.4×); reduction of about 30% of CRP values after probiotic intake. No statistical significance (p > 0.05). Higher basal CAL values; increased values after probiotic treatment. Significant increase of IgM (3×), but no changes in IgG and IgA serum levels. Reduction of CD4/CD8 ratio (mean index value = 1.78/2.06). d-ROM: slight reduction of mean values; great variability among patients. Patients with very low d-ROM values in T0 (Group A) increased oxidative production in T2; patients with normal d-ROM values at T0 (Group B) decreased oxidative production after treat. Group A had higher levels in BDI tests, higher CFQ, higher UC levels, and lower MCS/PCS of HR-QOL than Group B. No significant correlation between d-ROM and CFQ (p = 0.35, t =1.01), between d-ROM and BDI-I and BDI-II inventory (p = 0.39, t = 0.92; p = 0.18, t = 1.47, respectively), and between d-ROM and PCS indexes (p = 0.71, t = 0.39). Significant correlation between dROM and MCS (p = 0.04; t = 2.47). |

| Castro-Marrero et al., 2022 [57] | Biomarker assays (e.g., cholesterol, free T4) | Significant differences for LDL, cholesterol, TSH, and free T4. Significant increase in TAC (p < 0.001). Significant decrease in lipoperoxide content (p < 0.001) after treatment. Significant decreases in inflammatory cytokine levels (p < 0.01 for all) at eight-week follow-up. No significant differences in BLD CRP levels, FGF21, and NTproBNP (p > 0.05 for all). |

| Forsythe et al., 1999 [34] | RBC and WBC; erythrocyte sedimentation rate; serum chemistry; urinalysis; serum IgG, IgM, IgA, and IgE concentrations; enumeration and quantitation of CD3, CD4, CD8, CD19, and CD16/56); E1 enzyme assay; EBV-VCA; thyroid function levels; serum antibody titers to HHV-6, HIV, RF, and Hep B/C (HBS Ag, anti-HCV) | No correlation between immune function or clinical status nor treatment response. No differences in E1 activity before or after NADH treatments. 60% had EBV-EA = 40. 40% had HHV-6 titers = 1:160. 4% were anti-HCV positive. 100% were HIV-negative, and RF was negative. 13% had elevated levels of IgE. T4 and TSH levels were within normal limits for all subjects (100%). Immunologic testing was discontinued due to non-detectable abnormalities in serum immunoglobulin concentrations or lymphocyte subset analysis. |

| Vermeulen et al., 2004 [55] | BLD for free carnitine and carnitine esters in plasmas | Significant increase in plasma L-carnitine in all groups. Levels of the carnitine esters increased in all groups but remained low compared with L-carnitine. No sex differences. Change in the plasma L-carnitine concentration in the ALC group was inversely related to clinical improvement, but not in the other groups. Change in plasma carnitine was related to improvement of MFI-20 in the ALC group, but not in the PLC and ALCPLC group. Change in plasma carnitine was not related to change in COG or PAI. Plasma ALC and PLC were not related to CGI. |

| Ostojic et al., 2016 [51] | BLD and 24 h urine: serum and urinary GAA; creatine and creatinine; total serum homocysteine; RBC; WBC; platelets; hemoglobin; hematocrit; RBC indices; ESR; Glc; total cholesterol; triglycerides; lipoprotein levels; serum sodium; potassium; Ca; enzyme serum activities (AST; ALT; LDH; ALP; CK); urine protein, blood, and Glc | Significant effect of treat for all guanidino compounds (p < 0.05) except for urinary creatine (p > 0.05). After three months of treat, significant improvement of muscular creatine concentrations compared to cont (36% vs. 2%; p < 0.01). No effect of treat on blood Glc and lipid profiles, liver and muscle enzymes, hematological indices, and urinary analyses outcomes. |

| Fukuda et al., 2016 [49] | CoQ10 levels + serum oxidation activity (reactive oxygen metabolite-derived compounds) and antioxidant activity | PIL: significant increase in plasma CoQ10 levels compared to baseline (p < 0.05). RCT: significantly increased plasma CoQ10 concentrations (4×) for TREAT compared to CONT (p < 0.05). Significantly lower plasma ubiquinone levels in patients without any lifetime psychiatric disorders ([N = 13] = 0.07 ± 0.06 vs. [N = 6] = 0.17 ± 0.09; Z = −2.2, p = 0.03). |

| Castro-Marrero et al., 2015 [33] | BLD: NAD+/NADH levels + ratio; CoQ10 levels; TBARS levels; intracellular ATP; citrate synthase assay | NAD+/NADH (p < 0.001), CoQ10 (p < 0.05), ATP (p < 0.05), and citrate synthase (p < 0.05) were significantly higher. Lipoperoxides (p < 0.05) were significantly lower in blood mononuclear cells of treat. |

| No secondary measures | ||

| Cash and Kaufmann, 2022 [53] | NA | NA |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dorczok, M.C.; Mittmann, G.; Mossaheb, N.; Schrank, B.; Bartova, L.; Neumann, M.; Steiner-Hofbauer, V. Dietary Supplementation for Fatigue Symptoms in Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS)—A Systematic Review. Nutrients 2025, 17, 475. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17030475

Dorczok MC, Mittmann G, Mossaheb N, Schrank B, Bartova L, Neumann M, Steiner-Hofbauer V. Dietary Supplementation for Fatigue Symptoms in Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS)—A Systematic Review. Nutrients. 2025; 17(3):475. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17030475

Chicago/Turabian StyleDorczok, Marie Celine, Gloria Mittmann, Nilufar Mossaheb, Beate Schrank, Lucie Bartova, Matthias Neumann, and Verena Steiner-Hofbauer. 2025. "Dietary Supplementation for Fatigue Symptoms in Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS)—A Systematic Review" Nutrients 17, no. 3: 475. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17030475

APA StyleDorczok, M. C., Mittmann, G., Mossaheb, N., Schrank, B., Bartova, L., Neumann, M., & Steiner-Hofbauer, V. (2025). Dietary Supplementation for Fatigue Symptoms in Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS)—A Systematic Review. Nutrients, 17(3), 475. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17030475