Effects of Iodine Status and Vitamin A Level on Blood Pressure, Blood Glucose, and Blood Lipid Levels in Chinese Adults: A Cross-Sectional Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Participants

2.2. Measurements and Classifications

2.3. Other Covariates

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Participant Characteristics

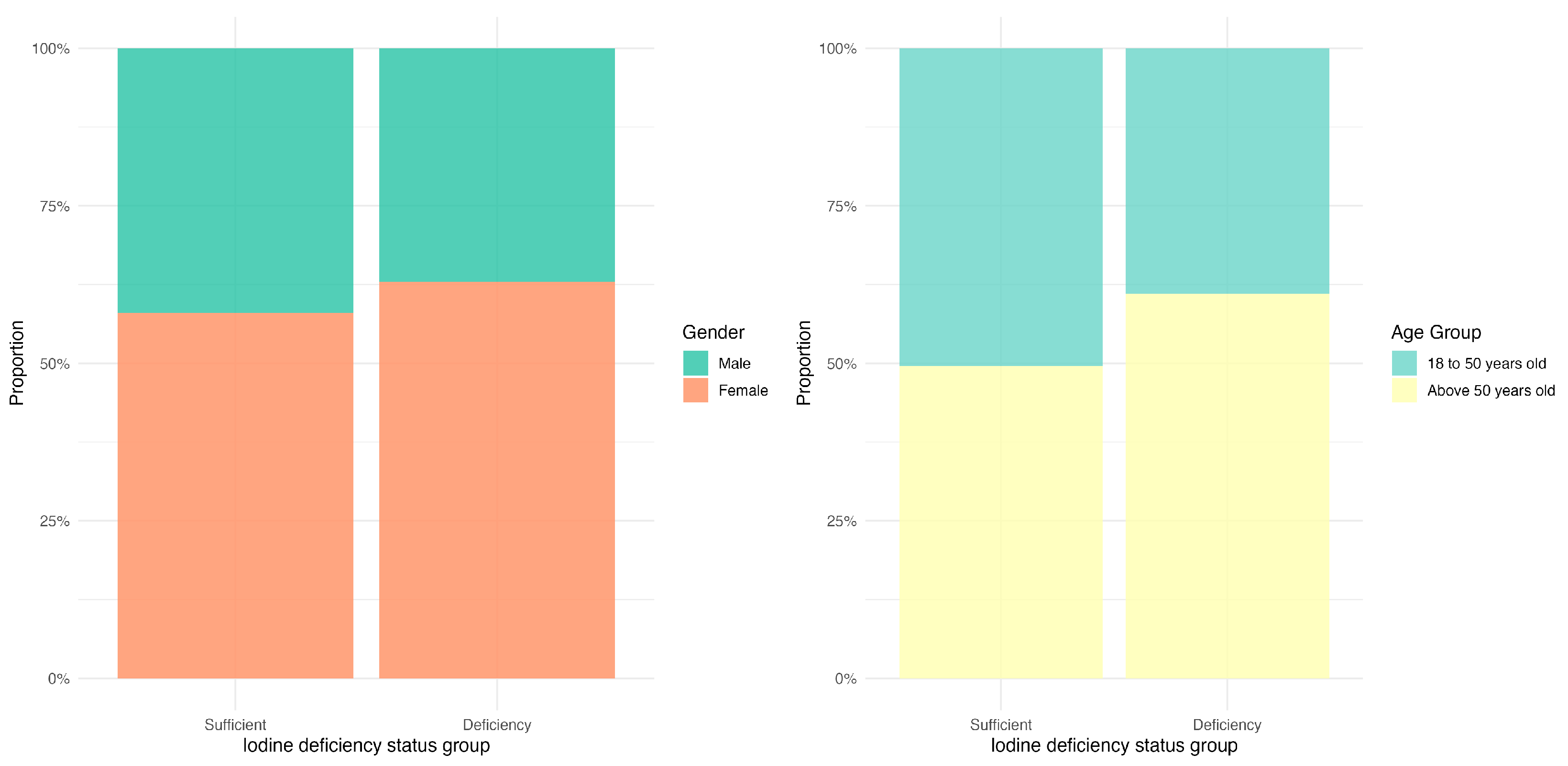

3.2. The Distribution of Iodine Deficiency Across Different Gender and Age Groups

3.3. Iodine Deficiency and Blood Pressure, Blood Glucose, and Blood Lipid Levels

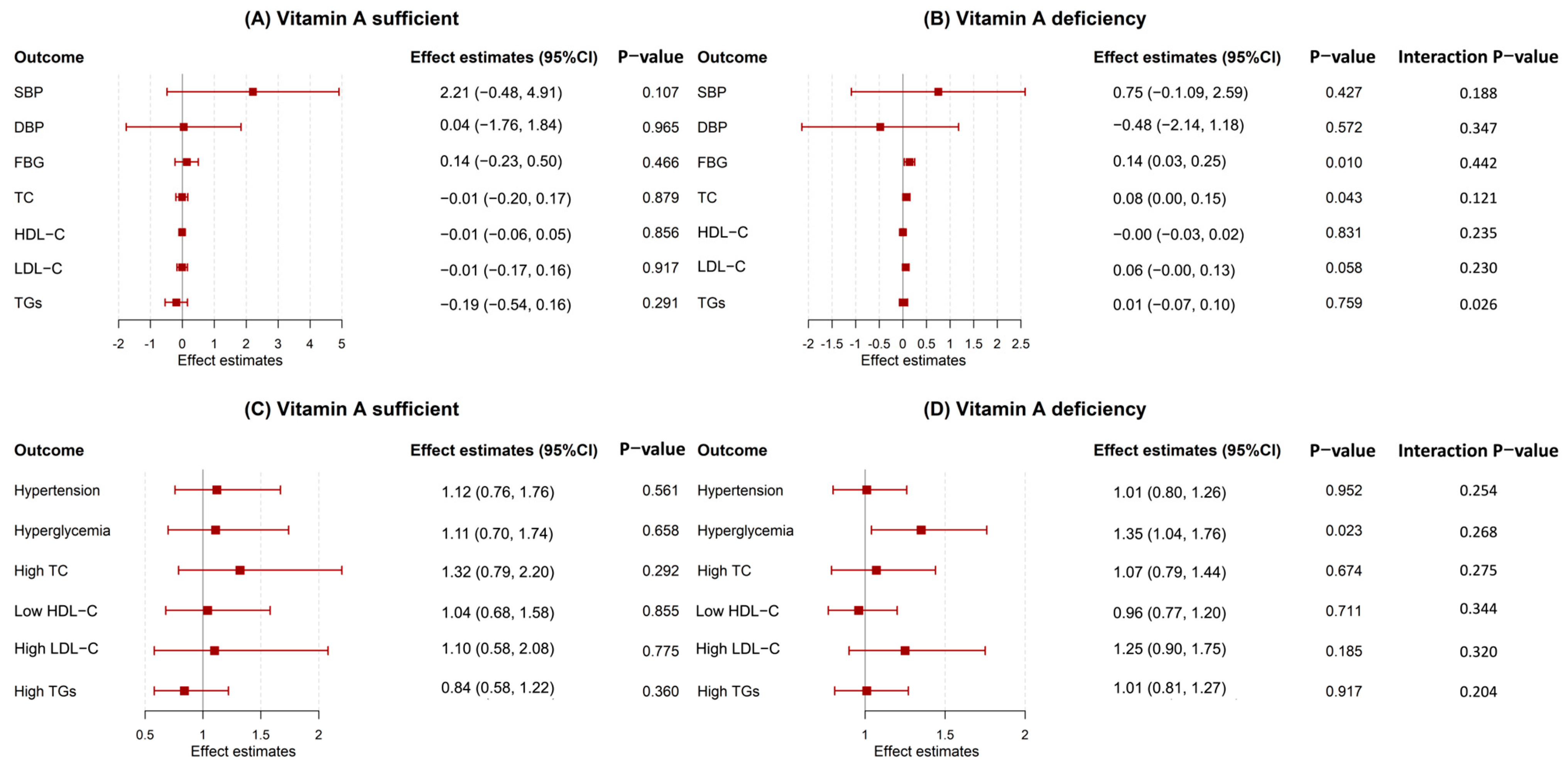

3.4. Stratified by Vitamin A Levels Groups

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- O’Kane, S.M.; Mulhern, M.S.; Pourshahidi, L.K.; Strain, J.J.; Yeates, A.J. Micronutrients, iodine status and concentrations of thyroid hormones: A systematic review. Nutr. Rev. 2018, 76, 418–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pironi, L.; Guidetti, M.; Agostini, F. Iodine status in intestinal failure in adults. Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care 2015, 18, 582–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winder, M.; Kosztyła, Z.; Boral, A.; Kocełak, P.; Chudek, J. The Impact of Iodine Concentration Disorders on Health and Cancer. Nutrients 2022, 14, 2209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Assessment of Iodine Deficiency Disorders and Monitoring Their Elimination: A Guide for Programme Managers; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2001.

- Pearce, E.N.; Lazarus, J.H.; Moreno-Reyes, R.; Zimmermann, M.B. Consequences of iodine deficiency and excess in pregnant women: An overview of current knowns and unknowns. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2016, 104 (Suppl. S3), 918s–923s. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perrine, C.G.; Sullivan, K.M.; Flores, R.; Caldwell, K.L.; Grummer-Strawn, L.M. Intakes of dairy products and dietary supplements are positively associated with iodine status among U.S. children. J. Nutr. 2013, 143, 1155–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monaghan, A.M.; Mulhern, M.S.; McSorley, E.M.; Strain, J.J.; Dyer, M.; van Wijngaarden, E.; Yeates, A.J. Associations between maternal urinary iodine assessment, dietary iodine intakes and neurodevelopmental outcomes in the child: A systematic review. Thyroid Res. 2021, 14, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldini, E.; Lauro, A.; Tripodi, D.; Pironi, D.; Amabile, M.I.; Ferent, I.C.; Lori, E.; Gagliardi, F.; Bellini, M.I.; Forte, F.; et al. Thyroid Diseases and Breast Cancer. J. Pers. Med. 2022, 12, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lai, X.; Zhang, L. Relationship between urinary iodine concentration and all-cause mortality in individuals with diabetes: An analysis of National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2005– 2018. Hormones 2025, 24, 775–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Candido, A.C.; Azevedo, F.M.; Ribeiro, S.A.V.; Navarro, A.M.; Macedo, M.S.; Fontes, E.A.F.; Crispim, S.P.; Carvalho, C.A.; Pizato, N.; da Silva, D.G.; et al. Iodine Deficiency and Excess in Brazilian Pregnant Women: A Multicenter Cross-Sectional Study (EMDI-Brazil). Nutrients 2025, 17, 2753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asvold, B.O.; Vatten, L.J.; Nilsen, T.I.; Bjøro, T. The association between TSH within the reference range and serum lipid concentrations in a population-based study. The HUNT Study. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 2007, 156, 181–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knudsen, N.; Laurberg, P.; Rasmussen, L.B.; Bulow, I.; Perrild, H.; Ovesen, L.; Jørgensen, T. Small differences in thyroid function may be important for body mass index and the occurrence of obesity in the population. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2005, 90, 4019–4024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Åsvold, B.O.; Bjøro, T.; Nilsen, T.I.L.; Gunnell, D.; Vatten, L.J. Thyrotropin levels and risk of fatal coronary heart disease: The HUNT study. Arch. Intern. Med. 2008, 168, 855–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herter-Aeberli, I.; Cherkaoui, M.; El Ansari, N.; Rohner, R.; Stinca, S.; Chabaa, L.; von Eckardstein, A.; Aboussad, A.; Zimmermann, M.B. Iodine Supplementation Decreases Hypercholesterolemia in Iodine-Deficient, Overweight Women: A Randomized Controlled Trial1,2. J. Nutr. 2015, 145, 2067–2075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanderpump, M.P.; Tunbridge, W.M.; French, J.M.; Appleton, D.; Bates, D.; Clark, F.; Grimley Evans, J.; Hasan, D.M.; Rodgers, H.; Tunbridge, F.; et al. The incidence of thyroid disorders in the community: A twenty-year follow-up of the Whickham Survey. Clin. Endocrinol. 1995, 43, 55–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopes, S.O.; Mayer, E.M.; Azevedo, F.M.; Candido, A.C.; Bittencourt, J.M.; Morais, D.C.; Franceschini, S.; Priore, S.E. Nutritional Status of Iodine and Association with Iron, Selenium, and Zinc in Population Studies: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutrients 2025, 17, 3432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dargenio, V.N.; Sgarro, N.; Grasta, G.; Begucci, M.; Castellaneta, S.P.; Dargenio, C.; Paulucci, L.; Francavilla, R.; Cristofori, F. Hidden Hunger in Pediatric Obesity: Redefining Malnutrition Through Macronutrient Quality and Micronutrient Deficiency. Nutrients 2025, 17, 3601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- English, K.; Uwibambe, C.; Daniels, P.; Dzukey, E. Scoping review of micronutrient imbalances, clinical manifestations, and interventions. World J. Methodol. 2025, 15, 107664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Chen, G. The Roles of Vitamin A in the Regulation of Carbohydrate, Lipid, and Protein Metabolism. J. Clin. Med. 2014, 3, 453–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Du, M.; Blumberg, J.B.; Chui, K.K.H.; Ruan, M.; Rogers, G.; Shan, Z.; Zeng, L.; Zhang, F.F. Association Among Dietary Supplement Use, Nutrient Intake, and Mortality Among U.S. Adults. Ann. Intern. Med. 2019, 170, 604–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Li, Y.; Chen, S.; Hu, N.; Liao, D. Vitamin A is associated with all-cause mortality in patients with chronic kidney disease: A population-based cohort study. Front. Nutr. 2024, 11, 1469844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradley, M.; Melchor, J.; Carr, R.; Karjoo, S. Obesity and malnutrition in children and adults: A clinical review. Obes. Pillars 2023, 8, 100087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farhangi, M.A.; Saboor-Yaraghi, A.A.; Keshavarz, S.A. Vitamin A supplementation reduces the Th17-Treg-Related cytokines in obese and non-obese women. Arch. Endocrinol. Metab. 2016, 60, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, G.; Zhou, C.; Huang, L.; Mo, Z.; Su, D.; Gu, S.; Guo, F.; Wang, Y.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, R.; et al. Role of Iodine Status and Lifestyle Behaviors on Goiter among Children and Adolescents: A Cross-Sectional Study in Zhejiang Province, China. Nutrients 2024, 16, 2910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, G.; Chen, M.; Huang, L.; Mo, Z.; Su, D.; Gu, S.; Guo, F.; Wang, Y.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, R.; et al. Differences in Vitamin A Levels and Their Association with the Atherogenic Index of Plasma and Subclinical Hypothyroidism in Adults: A Cross-Sectional Analysis in China. Nutrients 2024, 16, 2613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancia, G.; Kreutz, R.; Brunström, M.; Burnier, M.; Grassi, G.; Januszewicz, A.; Muiesan, M.L.; Tsioufis, K.; Agabiti-Rosei, E.; Algharably, E.A.E.; et al. 2023 ESH Guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension The Task Force for the management of arterial hypertension of the European Society of Hypertension: Endorsed by the International Society of Hypertension (ISH) and the European Renal Association (ERA). J. Hypertens. 2023, 41, 1874–2071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gietka-Czernel, M. The thyroid gland in postmenopausal women: Physiology and diseases. Prz. Menopauzalny 2017, 16, 33–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeJong, E.N.; Surette, M.G.; Bowdish, D.M. The gut microbiota and unhealthy aging: Disentangling cause from consequence. Cell Host Microbe 2020, 28, 180–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baksi, S.; Pradhan, A. Thyroid hormone: Sex-dependent role in nervous system regulation and disease. Biol. Sex Differ. 2021, 12, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pellanda, P.; Ghosh, T.S.; O’Toole, P.W. Understanding the impact of age-related changes in the gut microbiome on chronic diseases and the prospect of elderly-specific dietary interventions. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2021, 70, 48–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Otín, C.; Blasco, M.A.; Partridge, L.; Serrano, M.; Kroemer, G. The hallmarks of aging. Cell 2013, 153, 1194–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristoffer, F.; Falk, H.; Trine, N.; Gwen, F.; Emmanuelle, L.C.; Shinichi, S.; Edi, P.; Sara, V.-S.; Valborg, G.; Helle, K.P. Disentangling the effects of type 2 diabetes and metformin on the human gut microbiota. Nature 2015, 528, 262–266. [Google Scholar]

- O’Toole, P.W.; Jeffery, I.B. Microbiome–Health interactions in older people. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2018, 75, 119–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raza, M.H.; Gul, K.; Arshad, A.; Riaz, N.; Waheed, U.; Rauf, A.; Aldakheel, F.; Alduraywish, S.; Rehman, M.U.; Abdullah, M. Microbiota in cancer development and treatment. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2019, 145, 49–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaker, L.; Papaleontiou, M. Hypothyroidism: A Review. JAMA 2025, 334, 1750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köhrle, J. Selenium, Iodine and Iron-Essential Trace Elements for Thyroid Hormone Synthesis and Metabolism. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 3393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiersinga, W.M.; Poppe, K.G.; Effraimidis, G. Hyperthyroidism: Aetiology, pathogenesis, diagnosis, management, complications, and prognosis. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2023, 11, 282–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brenta, G.; Berg, G.; Arias, P.; Zago, V.; Schnitman, M.; Muzzio, M.L.; Sinay, I.; Schreier, L. Lipoprotein alterations, hepatic lipase activity, and insulin sensitivity in subclinical hypothyroidism: Response to L-T4 treatment. Thyroid 2007, 17, 453–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varlamov, O.; Bethea, C.L.; Roberts, C.T., Jr. Sex-specific differences in lipid and glucose metabolism. Front. Endocrinol. 2014, 5, 241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zitzmann, M.; Gromoll, J.; von Eckardstein, A.; Nieschlag, E. The CAG repeat polymorphism in the androgen receptor gene modulates body fat mass and serum concentrations of leptin and insulin in men. Diabetologia 2003, 46, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boese, A.C.; Kim, S.C.; Yin, K.J.; Lee, J.P.; Hamblin, M.H. Sex differences in vascular physiology and pathophysiology: Estrogen and androgen signaling in health and disease. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2017, 313, H524–H545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laughlin, G.A.; Barrett-Connor, E.; Bergstrom, J. Low serum testosterone and mortality in older men. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2008, 93, 68–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mårin, P.; Holmäng, S.; Gustafsson, C.; Jönsson, L.; Kvist, H.; Elander, A.; Eldh, J.; Sjöström, L.; Holm, G.; Björntorp, P. Androgen treatment of abdominally obese men. Obes. Res. 1993, 1, 245–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodpaster, B.H.; Park, S.W.; Harris, T.B.; Kritchevsky, S.B.; Nevitt, M.; Schwartz, A.V.; Simonsick, E.M.; Tylavsky, F.A.; Visser, M.; Newman, A.B. The loss of skeletal muscle strength, mass, and quality in older adults: The health, aging and body composition study. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2006, 61, 1059–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, G.I.; Julliand, S.; Reeds, D.N.; Sinacore, D.R.; Klein, S.; Mittendorfer, B. Fish oil-derived n-3 PUFA therapy increases muscle mass and function in healthy older adults. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2015, 102, 115–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elom, M.O.; Eyo, J.E.; Okafor, F.C.; Nworie, A.; Usanga, V.U.; Attamah, G.N.; Igwe, C.C. Improved infant hemoglobin (Hb) and blood glucose concentrations: The beneficial effect of maternal vitamin A supplementation of malaria-infected mothers in Ebonyi State, Nigeria. Pathog. Glob. Health 2017, 111, 45–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, S.; Zhou, Y.; Zhao, Q.; Chen, R.; Su, Z. Trends in three malnutrition factors in the global burden of disease: Iodine deficiency, vitamin A deficiency, and protein-energy malnutrition (1990–2019). Front. Nutr. 2024, 11, 1426790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capriello, S.; Stramazzo, I.; Bagaglini, M.F.; Brusca, N.; Virili, C.; Centanni, M. The relationship between thyroid disorders and vitamin A: A narrative minireview. Front. Endocrinol. 2022, 13, 968215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brossaud, J.; Pallet, V.; Corcuff, J.B. Vitamin A, endocrine tissues and hormones: Interplay and interactions. Endocr. Connect. 2017, 6, R121–R130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmermann, M.B.; Wegmüller, R.; Zeder, C.; Chaouki, N.; Torresani, T. The effects of vitamin A deficiency and vitamin A supplementation on thyroid function in goitrous children. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2004, 89, 5441–5447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phan, A.; Pesce, E.; Baumann, L.; Polakovičová, P.; Bednář, D.; Smutná, M.; Novák, J.; Hilscherová, K. Refining the AOP for retinoid-induced teratogenicity: Insights into RAR/RXR overactivation and RXR cross-talk with retinoic acid and thyroid hormone signaling. Aquat. Toxicol. 2025, 289, 107608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shulhai, A.M.; Rotondo, R.; Petraroli, M.; Patianna, V.; Predieri, B.; Iughetti, L.; Esposito, S.; Street, M.E. The Role of Nutrition on Thyroid Function. Nutrients 2024, 16, 2496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variables | Total (n = 4723) | No Vitamin A Data (n = 1459) | Vitamin A Sufficient (n = 554) | Vitamin A Deficiency (n = 2710) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Height (cm, mean ± SD) | 162.05 ± 8.37 | 160.42 ± 8.10 | 165.39 ± 8.16 | 162.24 ± 8.33 | <0.001 |

| Weight (kg, mean ± SD) | 62.64 ± 11.32 | 61.84 ± 11.08 | 67.24 ± 10.62 | 62.13 ± 11.36 | <0.001 |

| BMI (kg/m2, mean ± SD) | 23.80 ± 3.61 | 23.98 ± 3.55 | 24.53 ± 3.07 | 23.55 ± 3.72 | <0.001 |

| Sex (n (%)) | |||||

| Male | 1895 (40.12) | 549 (37.63) | 392 (70.76) | 954 (35.20) | <0.001 |

| Female | 2828 (59.88) | 910 (62.37) | 162 (29.24) | 1756 (64.80) | |

| Age group (n (%)) | |||||

| 18–50 years old | 2174 (46.03) | 560 (38.38) | 188 (33.94) | 1426 (52.62) | <0.001 |

| >50 years old | 2549 (53.97) | 899 (61.62) | 366 (66.06) | 1284 (47.38) | |

| SBP (mmHg) | 126.04 ± 21.97 | 130.97 ± 20.26 | 129.81 ± 15.24 | 122.62 ± 23.34 | <0.001 |

| DBP (mmHg) | 77.95 ± 17.43 | 80.14 ± 11.38 | 80.60 ± 10.05 | 76.24 ± 20.79 | <0.001 |

| FBG (mmol/L) | 5.28 ± 1.61 | 5.31 ± 1.78 | 5.70 ± 2.05 | 5.17 ± 1.39 | <0.001 |

| TC (mmol/L) | 4.91 ± 1.00 | 5.03 ± 1.05 | 5.15 ± 1.02 | 4.81 ± 0.95 | <0.001 |

| HDL-C (mmol/L) | 1.34 ± 0.35 | 1.33 ± 0.35 | 1.26 ± 0.34 | 1.37 ± 0.35 | <0.001 |

| LDL-C (mmol/L) | 2.81 ± 0.84 | 2.82 ± 0.89 | 2.87 ± 0.92 | 2.80 ± 0.80 | 0.075 |

| TGs (mmol/L) | 1.71 ± 1.52 | 1.81 ± 1.87 | 2.50 ± 1.95 | 1.49 ± 1.09 | <0.001 |

| Hypertension | |||||

| No | 3630 (76.87) | 944 (64.70) | 394 (71.25) | 2292 (84.58) | <0.001 |

| Yes | 1092 (23.13) | 515 (35.30) | 159 (28.75) | 418 (15.42) | |

| Hyperglycemia | |||||

| No | 3818 (85.57) | 1208 (82.91) | 432 (79.85) | 2178 (88.39) | <0.001 |

| Yes | 644 (14.43) | 249 (17.09) | 109 (20.15) | 286 (11.61) | |

| High TC | |||||

| No | 4275 (90.53) | 1291 (88.55) | 479 (86.46) | 2505 (92.44) | <0.001 |

| Yes | 447 (9.47) | 167 (11.45) | 75 (13.54) | 205 (7.56) | |

| Low HDL-C | |||||

| No | 3830 (81.11) | 1180 (80.93) | 405 (73.10) | 2245 (82.84) | <0.001 |

| Yes | 892 (18.89) | 278 (19.07) | 149 (26.90) | 465 (17.16) | |

| High LDL-C | |||||

| No | 4423 (93.67) | 1362 (93.42) | 508 (91.70) | 2553 (94.21) | 0.033 |

| Yes | 299 (6.33) | 96 (6.58) | 46 (8.30) | 157 (5.79) | |

| High TGs | |||||

| No | 3770 (79.84) | 1145 (78.53) | 319 (57.58) | 2306 (85.09) | <0.001 |

| Yes | 952 (20.16) | 313 (21.47) | 235 (42.42) | 404 (14.91) | |

| Smoking status (n (%)) | |||||

| Smoke every day | 635 (13.44) | 193 (13.23) | 156 (28.16) | 286 (10.55) | <0.001 |

| Smoke occasionally | 82 (1.74) | 27 (1.85) | 15 (2.71) | 40 (1.48) | |

| Do not smoke now | 258 (5.46) | 63 (4.32) | 55 (9.93) | 140 (5.17) | |

| Never smoke | 3521 (74.55) | 1175 (80.53) | 320 (57.76) | 2026 (74.76) | |

| Missing | 227 (4.81) | 1 (0.07) | 8 (1.44) | 218 (8.04) | |

| Dietary habits | |||||

| Frequently consume seafood | 1004 (21.26) | 260 (17.82) | 136 (24.55) | 608 (22.44) | <0.001 |

| Frequently eat pickled foods | 179 (3.79) | 46 (3.15) | 31 (5.60) | 102 (3.76) | |

| Frequently drink vegetable soup | 387 (8.19) | 189 (12.95) | 42 (7.58) | 156 (5.76) | |

| Others | 2702 (57.21) | 596 (40.85) | 344 (62.09) | 1762 (65.02) | |

| Missing | 451 (9.55) | 368 (25.22) | 1 (0.18) | 82 (3.03) | |

| Sleeping time | |||||

| ≥8 h | 3170 (67.12) | 756 (51.82) | 395 (71.30) | 2019 (74.50) | <0.001 |

| <8 h | 1092 (23.12) | 330 (22.62) | 156 (28.16) | 606 (22.36) | |

| Missing | 461 (9.76) | 373 (25.57) | 3 (0.54) | 85 (3.14) | |

| Vitamin D levels (n (%)) | |||||

| Sufficient | 1166 (25.10) | 463 (33.36) | 188 (34.06) | 515 (19.03) | <0.001 |

| Deficiency | 3480 (74.90) | 925 (66.64) | 364 (65.94) | 2191 (80.97) |

| Outcome | Adjusted Model | |

|---|---|---|

| β (95%CI) | p Value | |

| SBP | 2.89 (2.00–3.77) | <0.001 |

| DBP | 1.08 (0.55–1.60) | <0.001 |

| FBG | 0.06 (0.01–0.12) | 0.031 |

| TC | 0.05 (0.00–0.10) | 0.033 |

| HDL-C | 0.00 (−0.02–0.01) | 0.738 |

| LDL-C | 0.04 (−0.01–0.08) | 0.099 |

| TGs | 0.00 (−0.06–0.05) | 0.882 |

| OR (95% CI) | pValue | |

| Hypertension | 1.41 (1.23–1.63) | <0.001 |

| Hyperglycemia | 1.39 (1.17–1.65) | <0.001 |

| High TC | 1.09 (0.89–1.33) | 0.404 |

| Low HDL-C | 0.95 (0.81–1.11) | 0.521 |

| High LDL-C | 1.06 (0.83–1.35) | 0.652 |

| High TGs | 1.03 (0.89–1.20) | 0.665 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhao, J.; Chen, M.; Peng, Y.; Han, K.; Lu, Q.; Dong, B. Effects of Iodine Status and Vitamin A Level on Blood Pressure, Blood Glucose, and Blood Lipid Levels in Chinese Adults: A Cross-Sectional Study. Nutrients 2025, 17, 3948. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17243948

Zhao J, Chen M, Peng Y, Han K, Lu Q, Dong B. Effects of Iodine Status and Vitamin A Level on Blood Pressure, Blood Glucose, and Blood Lipid Levels in Chinese Adults: A Cross-Sectional Study. Nutrients. 2025; 17(24):3948. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17243948

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhao, Jingtao, Manman Chen, Yang Peng, Keyu Han, Qu Lu, and Bin Dong. 2025. "Effects of Iodine Status and Vitamin A Level on Blood Pressure, Blood Glucose, and Blood Lipid Levels in Chinese Adults: A Cross-Sectional Study" Nutrients 17, no. 24: 3948. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17243948

APA StyleZhao, J., Chen, M., Peng, Y., Han, K., Lu, Q., & Dong, B. (2025). Effects of Iodine Status and Vitamin A Level on Blood Pressure, Blood Glucose, and Blood Lipid Levels in Chinese Adults: A Cross-Sectional Study. Nutrients, 17(24), 3948. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17243948