Dietary Patterns of Docosahexaenoic Acid Intake and Supplementation from Pregnancy Through Childhood with a Focus on Low- and Middle-Income Countries: A Narrative Review of Implications for Child Health

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Global DHA Intake

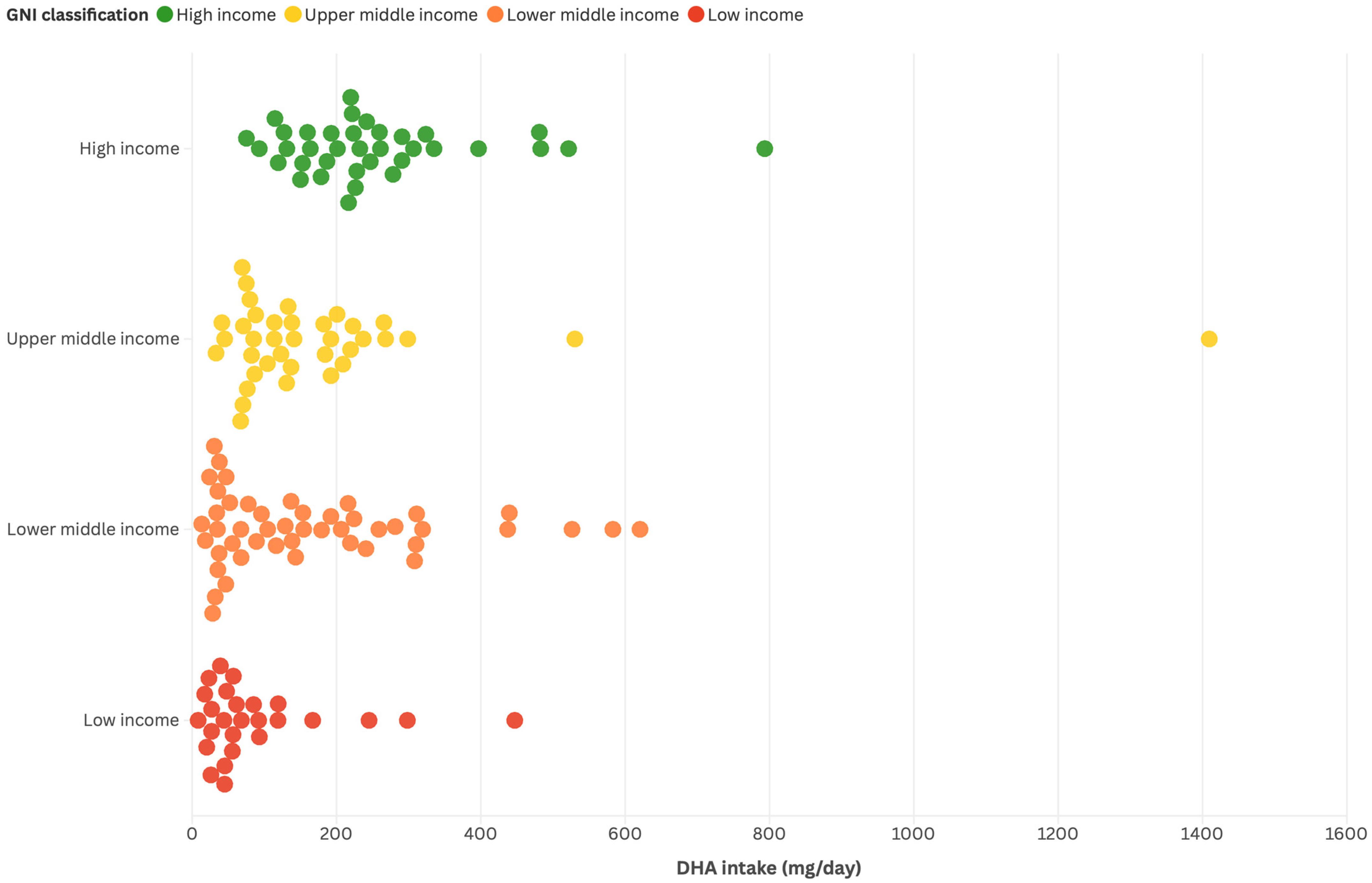

3.1. Comparison by Country Income Level

3.2. DHA Intake in Children

Patterns of DHA by Country Income Level

| Author, Year, Country | GNI | Domain | Study Design | Life Stage | DHA Assessment | Reported Diet and/or Biomarkers | Main Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yuan, 2022 [72] France | High income | Dietary patterns and biomarkers | Cohort study (EDEN mother–child cohort, n ≈ 2000) | Children (perinatal: maternal pregnancy) | Biomarkers (maternal RBC membrane, cord RBC membrane, colostrum) | Patterns of dairy product consumption during pregnancy (derived from FFQ + PCA): Cheese Reduced-fat dairy products Semi-skimmed milk and yogurt | Maternal RBC membrane: Cheese β = −0.01 (95% CI: −0.05, 0.07); Reduced-fat DP β = 0.10 (95% CI: 0.06, 0.15); Semi-skimmed milk/yogurt β = 0.10 (95% CI: 0.05, 0.14). Cord blood RBC membrane: Cheese β = 0.02 (95% CI: −0.04, 0.09); Reduced-fat DP β = 0.06 (95% CI: 0.02, 0.11); Semi-skimmed milk/yogurt β = 0.05 (95% CI: 0.00, 0.10). Colostrum: Cheese β = −0.02 (95% CI: −0.09, 0.05); Reduced-fat DP β = 0.03 (95% CI: 0.02, 0.09); Semi-skimmed milk/yogurt β = 0.04 (95% CI: −0.02, 0.09). Note: Associations reflect dietary pattern correlations with DHA status and should not be interpreted as direct evidence of DHA content in dairy foods. * Adjusted for study center, maternal age, sampling day (colostrum), maternal healthy dietary pattern, and fish consumption; sensitivity analyses excluded gestational diabetes, hypertensive disorders, extreme energy intake, and preterm delivery. |

| Mulder, 2022 Canada [45] | High income | Neurodevelopment | Cross-sectional study (with follow-up subgroup from a previous RCT) | Children, 5–6 years (mean 5.75 y) | Dietary assessment: FFQ (n = 280), 1 × 24 h recall (n = 272), 3 × 24 h recalls (n = 259) Biomarker: RBC fatty acids (n = 245), measured by gas–liquid chromatography. | DHA intake (mg/day) RBC DHA (% total fatty acids): | Median DHA intake: 52.9 mg/day (FFQ) and 19.5 mg/day (24 h recall; p < 0.001). RBC DHA and cognitive outcomes: Higher RBC DHA was associated with better short-term memory (KABC Sequential, rho = 0.187, p = 0.019) and vocabulary (PPVT, rho = 0.211, p = 0.009). Q5 vs. Q1 RBC DHA memory scores: 5.80% ± 1.51% vs. 4.93% ± 1.34%, p = 0.012. Dietary DHA correlations: Dietary DHA correlated with memory (rho = 0.221, p = 0.003). Ethnic differences: RBC DHA was higher in Chinese (6.06% ± 1.42%) vs. White children (5.38% ± 1.52%), p = 0.013. * Adjusted for ethnicity and relevant child/family characteristics (e.g., parental IQ, household composition); analyses restricted to White children in some models. |

| Huang, 2022 China [25] | Upper-middle-income | Intake | Cross-sectional study | Children (5–7 years) | Plasma and erythrocytes (Gas Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry) | Diversified pattern: high intakes of fruits, nuts, leafless vegetables, poultry, fungi and algae, fresh beans, tubers, fish, meat, soybeans and products, snacks, rice, shrimp, crab, shellfish Plant pattern: coarse cereals, soybeans and products, leafless vegetables, tubers; low poultry and meat Beverage/snack pattern: high beverages, snacks, milk and products; low shrimp, crab, shellfish, fish | Median DHA levels: Plasma 7.91 µg/mL (IQR 6.22–10.45), RBC 13.89 µg/mL (IQR 7.49–18.99). Diversified dietary pattern: positively associated with plasma DHA (β = 0.145, 95% CI: 0.045–0.244, p = 0.004); correlations with eggs, meat, poultry, and fish. Beverage/snack pattern: weak negative association with plasma DHA (β = −0.092, 95% CI: −0.187–0.003, ~p = 0.05). Risk patterns: plasma DHA inversely related to obesity risk pattern (OR = 0.873, 95% CI: 0.786–0.969, p = 0.011) but positively associated with blood lipid risk pattern (OR = 1.271, 95% CI: 1.142–1.415, p < 0.001). RBC DHA: limited associations; only significant with blood lipid risk pattern: (OR = 1.043, 95% CI: 1.002–1.086, p = 0.040) * Adjusted for age, sex, caregiver, caregiver’s education and occupation, family economic level; additional adjustment for meat, poultry, eggs, and fish intake in some model |

| Forsyth, 2016 [86] Multi-country (175 nations, global analysis). | 175 countries, grouped by World Bank classification: high, upper-middle, lower-middle, and low income. | Intake (national per capita DHA availability) | Ecological study using FAO FBS (2009–2011), fatty-acid composition from NUTTAB 2010, adjusted for retail/household wastage | Not applicable (national-level ecological estimates) | Estimated per capita DHA availability from FAO FBS combined with food fatty-acid composition tables (NUTTAB 2010) | Dietary availability only (no individual dietary surveys; no biomarkers) | Global DHA intake (by GNI): High-income: 192 mg/day (range: 67–706; n = 42) Upper-middle-income: 122 mg/day (range: 31–371; n = 49) Lower-middle-income: 134 mg/day (range: 13–605; n = 53) Low-income: 47 mg/day (range: 6–437; n = 28) Extremes: Highest intake: Maldives (1409.3 mg/day) Lowest intake: Ethiopia (7.01 mg/day) Sub-Saharan Africa: several countries with intakes < 50 mg/day; Ethiopia lowest (7.0 mg/day). Southern, Western, and Central Asia: many countries within 20–60 mg/day, reflecting very limited DHA intake. Small island states: highest median intake, 204.7 mg/day, consistent with reliance on marine foods. Latin America: median 134.2 mg/day (range: 28–561). Peru: 208.9 mg/day (highest); Guatemala: 28.4 mg/day; Paraguay: 37.7 mg/day (lowest) Sources and modifiers: Fish and seafood: main contributors to DHA supply worldwide. Landlocked countries: substantially lower intake (median 47.4 mg/day). Correlations: National birth rates negatively associated with DHA intake (r = −0.277; p < 0.001). * No individual adjustment; ecological estimates based on FAO FBS, corrected for wastage; stratified by GNI, geography (coastal vs. landlocked), and birth rates. |

| Mak, 2020 Canada [31] | High income | General development | Cross-sectional analysis (baseline data of an intervention trial) | Children with obesity (n = 63, 6–13 years, Tanner stages 1–3) | Dietary intake (3-day food diaries) and RBC fatty acids (gas chromatography) | Fish/seafood intake (servings/day) Dietary EPA, DHA, and EPA + DHA (mg/day) RBC EPA, DHA, and EPA + DHA (% of total fatty acids) | Adiposity and DHA: Higher body fat percentage was associated with lower RBC DHA (Tertile 1: 2.45% ± 0.84% vs. Tertile 3: 1.86% ± 0.35%; p < 0.05) and lower RBC EPA + DHA (Tertile 1: 2.24% ± 0.86% vs. Tertile 3: 1.86% ± 0.35%; p < 0.05). Diet–biomarker correlations: Dietary DHA correlated positively with RBC DHA (r = 0.37; p = 0.003). Each additional serving of fish increased RBC EPA + DHA by 1.1% (p = 0.0005). Dietary patterns: Children with higher adiposity consumed less fish (0.2 ± 0.04 servings/day) and had lower fruit/vegetable intake (p = 0.02). * Adjusted for age, sex, Tanner stage, race, and DXA-measured body fat; analyses stratified by sex and adiposity tertiles. |

| Soe, 2020 Myanmar [32] | Upper-middle-income | General development | Cross sectional study | Children (primary school) | Dietary intake modeling (24 h recall, 5-day food record, weighed records, nutrient composition tables from Vietnam and USDA) | Reported food groups tested in Optifood modeling Fish (carp, eel) identified as only foods contributing meaningful preformed DHA Other foods (shrimp, duck eggs, water spinach, peas) included in nutrient-dense combinations, but not as DHA sources | Nutrient-dense food combinations: Optimized diets included carp fish (7×/week), eel, shrimp (5×/week), duck eggs (3×/week), water spinach (4×/week), peas (4×/week). DHA adequacy: Even with optimized diets, DHA intake reached only ~26% of the RNI. Note: Carp fish and eel were the only direct dietary sources of DHA; other foods in the modeled combinations contributed to nutrient adequacy but not to DHA. * No individual adjustment; linear programming model using Optifood with constraints for food availability, affordability, cultural patterns, and nutrient composition. |

| Ogaz-Gonzalez, 2018 [75] Mexico | Upper-middle-income | Neurodevelopment | Cohort study (n = 142 mother–child pairs) | Pregnancy/Children (42–60 months) | Dietary intake (FFQ, 1st and 3rd trimester); Interaction analyses with maternal serum DDE | Reported diet DHA intake | Maternal intake: 35.1 mg/day (1st trimester) and 31.5 mg/day (3rd trimester). Effect modification: Low maternal DHA intake amplified the negative association between prenatal DDE exposure and motor development. Associations: Low-DHA group: β = −1.25 (95% CI: −2.62, −0.12). High-DHA group: β = 0.50 (95% CI: −0.55, 1.56). Sex differences: Protective effect of higher DHA intake was particularly observed in girls. Adjusted for child’s age at exam, HOME score, sex, maternal IQ, breastfeeding, energy intake, and maternal DDE levels; sensitivity analyses adjusted DHA/ARA for other PUFAs and stratified by sex. |

| Hakola, 2017 [76] Finland | High income | General development | Prospective cohort study (DIPP birth cohort, n ≈ 3807) | Pregnancy (maternal diet during late pregnancy), offspring childhood | Maternal dietary intake estimated with FFQ; nutrient composition from Finnish Food Composition Database | Reported dietary DHA intake (from fish and other food sources) | Maternal DHA intake (late pregnancy): Mean intake was 123 mg/day in children with obesity vs. 126 mg/day in children without obesity; no association with childhood obesity. Boys: Maternal DHA intake was 124 mg/day in boys with obesity vs. 125 mg/day in boys without obesity; no association observed. Girls: Maternal DHA intake was 122 mg/day in girls with obesity vs. 127 mg/day in girls without obesity; no association observed. * Adjusted for maternal early pregnancy BMI, gestational weight gain, timing of first weight measurement, glucose intolerance diet, education, smoking during pregnancy, and breastfeeding duration; analyses stratified by sex. |

| Gershuni, 2021 [81] USA | High income | General development | Prospective cohort with embedded case–control study (cases = 16 women with SPTB; controls = 32 women with term delivery, matched by race and obesity) | Pregnancy (second trimester, 20–26 weeks gestation) | Dietary intake (three 24 h recalls) Fecal and plasma metabolomics | Dietary exposures (3 × 24 h recalls, NDSR): total ω-3 fatty acids, DHA, EPA, saturated fat (palmitate), fiber, total energy intake. Supplements: all participants reported prenatal vitamin use (DHA content not captured in recalls). Biomarkers: fecal untargeted metabolomics (including DHA, EPA); plasma untargeted metabolomics. | Dietary intake: Women with SPTB had slightly higher DHA intake than controls, but levels remained very low in both groups (0.18 ± 0.34 g/day vs. 0.11 ± 0.25 g/day; p = 0.370). Total ω-3 intake was higher in SPTB cases (2.65 ± 1.05 vs. 1.89 ± 0.89 g/day; p = 0.014). Saturated fat intake was also higher in SPTB (31.38 ± 7.37 vs. 26.08 ± 8.62 g/day; p = 0.045). Fecal biomarkers: Women with SPTB showed higher fecal DHA and EPA levels (FDR < 0.20) despite low reported intake (<0.2 g/day). Plasma biomarkers: Elevated DHA-derived plasma metabolites were identified in SPTB cases, suggesting alterations in fatty acid metabolism. Correlations: Fecal DHA/EPA were positively correlated with saturated fat intake (p < 0.05) Matched for race/ethnicity and prepregnancy BMI; controls excluded if pregnancy complications; dietary data cleaned for implausible energy intake. |

| Hautero, 2017 [38] Finland | High income | Intake | Cross-sectional study (mothers in late pregnancy and infants at 1 month) | Pregnancy and lactation/early infancy | Biomarkers (serum phospholipids DHA in mothers and infants, GC analysis) | Fish intake frequency (0, 1, 2, 3, ≥4 times/week) Healthy Eating Index score (tertiles) 3-day food diaries and FFQ for dietary intake | Maternal serum phospholipid DHA: Frequent maternal fish intake (≥3×/week or ≥36 g/day) significantly increased DHA levels compared with low intake (p < 0.001). Infant serum phospholipid DHA: Infants of mothers with higher fish intake also showed significantly higher DHA levels at 1 month of age (p < 0.001). Correlation: Maternal and infant DHA were strongly correlated (R = 0.582, p < 0.001). * Adjusted for maternal age, pre-pregnancy BMI, parity, and education; GEE used for persistent fish intake and diet quality analyses. |

3.3. The Role of DHA in Child Health

3.3.1. General Development and DHA Dietary Intake

3.3.2. General Development and DHA Supplementation

3.3.3. Neurodevelopment and DHA Dietary Intake

3.3.4. Neurodevelopment and DHA Supplementation

3.3.5. Immune System Modulation and DHA

3.4. Maternal DHA Intake and Pregnancy Outcomes

3.4.1. Patterns of DHA Intake During Pregnancy and Its Fetal Implications

3.4.2. DHA and Its Association with Fetal Growth and General Development

3.4.3. Metabolic and Epigenetic Effects of Prenatal DHA

3.4.4. Maternal DHA Supplementation and Its Impact on Infant Immunity

3.4.5. Maternal DHA Supplementation and Neurodevelopmental Outcomes

3.5. DHA in Breast Milk and Infant Health Outcomes

3.5.1. Maternal DHA Intake and Composition of Human Milk

3.5.2. DHA in Breast Milk and Child Health Outcomes

3.6. Strengths and Limitations

4. Conclusions and General Considerations for Public Health

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ADHD | Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder |

| ADORE | Assessment of DHA on Reducing Early Preterm Birth (clinical trial) |

| ALA | Alpha-linolenic Acid |

| ARA | Arachidonic Acid |

| BMI | Body Mass Index |

| CC | Homozygous Genotype (context-dependent) |

| CI | Confidence Interval |

| DDE | 1,1-dichloro-2,2-bis (p-chlorophenyl)ethylene |

| DHA | Docosahexaenoic Acid |

| DMR | Differentially Methylated Region |

| DP | Dietary Patterns |

| DXA | Dual-Energy X-ray Absorptiometry |

| ENSANUT | Mexican National Health and Nutrition Survey |

| EPA | Eicosapentaenoic Acid |

| FADS | Fatty Acid Desaturase |

| FAO | Food and Agriculture Organization |

| FBS | Food Balance Sheets |

| FDR | False Discovery Rate |

| GEE | Generalized Estimating Equations |

| GNI | Gross National Income |

| HDL | High-Density Lipoprotein |

| HICs | High-Income Countries |

| HOME | Home Observation for Measurement of the Environment |

| IQ | Intelligence Quotient |

| IQR | Interquartile Range |

| IRR | Incidence Rate Ratio |

| KABC | Kaufman Assessment Battery for Children |

| LA | Linoleic Acid |

| LCPUFA | Long-Chain Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids |

| LDL | Low-Density Lipoprotein |

| LMICs | Low- and Middle-Income Countries |

| MeSH | Medical Subject Headings |

| MSCA | McCarthy Scales of Children’s Abilities |

| NDSR | Nutrition Data System for Research |

| NAFLD | Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease |

| OR | Odds Ratio |

| PCA | Principal Component Analysis |

| PICOS | Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome, Study Design |

| PPVT | Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| PTB | Preterm Birth |

| PUFAs | Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids |

| RBC | Red Blood Cells |

| RCT | Randomized Controlled Trial |

| RNI | Reference Nutrient Intake |

| SPTB | Spontaneous Preterm Birth |

| TC | Total Cholesterol |

| TCA | Tricarboxylic Acid |

| TNF | Tumor Necrosis Factor |

| TT | Homozygous Genotype (for T allele) |

| USDA | United States Department of Agriculture |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

References

- Innis, S.M. Impact of Maternal Diet on Human Milk Composition and Neurological Development of Infants. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2014, 99, 734S–741S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, K.R.; Harslof, L.B.S.; Schnurr, T.M.; Hansen, T.; Hellgren, L.I.; Michaelsen, K.F.; Lauritzen, L. A Study of Associations between Early DHA Status and Fatty Acid Desaturase (FADS) SNP and Developmental Outcomes in Children of Obese Mothers. Br. J. Nutr. 2017, 117, 278–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallick, R.; Basak, S.; Duttaroy, A.K. Docosahexaenoic Acid,22:6n-3: Its Roles in the Structure and Function of the Brain. Int. J. Dev. Neurosci. 2019, 79, 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basak, S.; Mallick, R.; Banerjee, A.; Pathak, S.; Duttaroy, A.K. Maternal Supply of Both Arachidonic and Docosahexaenoic Acids Is Required for Optimal Neurodevelopment. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Innis, S.M. Dietary (n-3) Fatty Acids and Brain Development 1,2. J. Nutr. 2007, 137, 855–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiser, M.J.; Butt, C.M.; Mohajeri, M.H. Docosahexaenoic Acid and Cognition throughout the Lifespan. Nutrients 2016, 8, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wendołowicz, A.; Stefańska, E.; Ostrowska, L. Influence of Selected Dietary Components on the Functioning of the Human Nervous System. Rocz. Państw. Zakł. Hig. 2018, 69, 15–21. [Google Scholar]

- Forsyth, S.; Calder, P.C.; Zotor, F.; Amuna, P.; Meyer, B.; Holub, B. Dietary Docosahexaenoic Acid and Arachidonic Acid in Early Life: What Is the Best Evidence for Policymakers? Ann. Nutr. Metab. 2018, 72, 210–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kris-Etherton, P.M.; Grieger, J.A.; Etherton, T.D. Dietary Reference Intakes for DHA and EPA. Prostaglandins Leukot. Essent. Fat. Acids 2009, 81, 99–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Domenichiello, A.F.; Kitson, A.P.; Bazinet, R.P. Is Docosahexaenoic Acid Synthesis from α-Linolenic Acid Sufficient to Supply the Adult Brain? Prog Lipid Res 2015, 59, 54–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Institutes of Health. Omega-3 Fatty Acids—Health Professional Fact Sheet. Available online: https://ods.od.nih.gov/factsheets/Omega3FattyAcids-HealthProfessional/ (accessed on 8 June 2025).

- FAO; WHO. Fats and Fatty Acids in Human Nutrition: Report of an Expert Consultation; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Michaelsen, K.F.; Dewey, K.G.; Perez-Exposito, A.B.; Nurhasan, M.; Lauritzen, L.; Roos, N. Food Sources and Intake of N-6 and n-3 Fatty Acids in Low-Income Countries with Emphasis on Infants, Young Children (6–24 Months), and Pregnant and Lactating Women. Matern. Child Nutr. 2011, 7, 124–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Landa-Gómez, N.; Barragán-Vázquez, S.; Salazar-Piña, A.; Olvera-Mayorga, G.; Gómez-Humarán, I.M.; Carriquiry, A.; Da Silva Gomes, F.; Ramírez-Silva, I. Intake of Trans Fats and Other Fatty Acids in Mexican Adults: Results from the 2012 and 2016 National Health and Nutrition Surveys. Salud Publica Mex. 2024, 66, 256–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colombo, S.M.; Rodgers, T.F.M.; Diamond, M.L.; Bazinet, R.P.; Arts, M.T. Projected Declines in Global DHA Availability for Human Consumption as a Result of Global Warming. Ambio 2020, 49, 865–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richard, C.; Lewis, E.D.; Field, C.J. Evidence for the Essentiality of Arachidonic and Docosahexaenoic Acid in the Postnatal Maternal and Infant Diet for the Development of the Infant’s Immune System Early in Life. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 2016, 41, 461–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Shi, M.Q.; Li, Z.H.; Yang, J.J.; Li, D. Fish, Long-Chain n-3 PUFA and Incidence of Elevated Blood Pressure: A Meta-Analysis of Prospective Cohort Studies. Nutrients 2016, 8, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitguard, S.; Doucette, O.; Miklavcic, J. Human Milk Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids Are Related to Neurodevelopmental, Anthropometric, and Allergic Outcomes in Early Life: A Systematic Review. J. Dev. Orig. Health Dis. 2023, 14, 763–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macaron, T.; Giudici, K.V.; Bowman, G.L.; Sinclair, A.; Stephan, E.; Vellas, B.; de Souto Barreto, P. Associations of Omega-3 Fatty Acids with Brain Morphology and Volume in Cognitively Healthy Older Adults: A Narrative Review. Ageing Res. Rev. 2021, 67, 101300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, C.; Afonso, C.; Bandarra, N.M. Dietary DHA and Health: Cognitive Function Ageing. Nutr. Res. Rev. 2016, 29, 281–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cardoso, C.; Afonso, C.; Bandarra, N.M. Dietary DHA, Bioaccessibility, and Neurobehavioral Development in Children. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2018, 58, 2617–2631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brenna, J.T.; Carlson, S.E. Docosahexaenoic Acid and Human Brain Development: Evidence That Adietary Supply Is Needed for Optimal Development. J. Hum. Evol. 2014, 77, 99–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Covidence Systematic Review Software, Veritas Health Innovation, Melbourne, Australia. Available online: www.covidence.org (accessed on 3 December 2025).

- World Health Organizationn. Child and Adolescent Health and Wellbeing; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Z.; Guo, P.; Wang, Y.; Li, Z.; Yin, X.; Chen, M.; Liu, Y.; Hu, Y.; Chen, B. Docosahexaenoic Acid as the Bidirectional Biomarker of Dietary and Metabolic Risk Patterns in Chinese Children: A Comparison with Plasma and Erythrocyte. Nutrients 2022, 14, 3095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mashavave, G.; Kuona, P.; Tinago, W.; Stray-Pedersen, B.; Munjoma, M.; Musarurwa, C. Dried Blood Spot Omega-3 and Omega-6 Long Chain Polyunsaturated Fatty Acid Levels in 7–9 Year Old Zimbabwean Children: A Cross Sectional Study. BMC Clin. Pathol. 2016, 16, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salomón, M.F.; Lazcano, A.K.; Peña, P.; Barrón, E.M.; Martínez-López, E.; Mendoza, G.G.; Ríos, E.; Ortiz, F.M.; Osuna, K.Y.; Osuna, I. Erythrocyte and Dietary Omega-3 Fatty Acid Profile in Overweight and Obese Pregnant Women. Nutr. Hosp. 2025, 42, 67–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henjum, S.; Lie, Ø.; Ulak, M.; Thorne-Lyman, A.L.; Chandyo, R.K.; Shrestha, P.S.; Fawzi, W.W.; Strand, T.A.; Kjellevold, M. Erythrocyte Fatty Acid Composition of Nepal Breast-Fed Infants. Eur. J. Nutr. 2018, 57, 1003–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solomons, N.W.; Bailey, E.; Soto Méndéz, M.J.; Campos, R.; Kraemer, K.; Salem, N. Erythrocyte Fatty Acid Status in a Convenience Sample of Residents of the Guatemalan Pacific Coastal Plain. Prostaglandins Leukot. Essent. Fat. Acids 2015, 98, 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vidakovic, A.J.; Gishti, O.; Steenweg-de Graaff, J.; Williams, M.A.; Duijts, L.; Felix, J.F.; Hofman, A.; Tiemeier, H.; Jaddoe, V.W.V.; Gaillard, R. Higher Maternal Plasma N-3 PUFA and Lower n-6 PUFA Concentrations in Pregnancy Are Associated with Lower Childhood Systolic Blood Pressure. J. Nutr. 2015, 145, 2362–2368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mak, I.L.; Cohen, T.R.; Vanstone, C.A.; Weiler, H.A. Increased Adiposity in Children with Obesity Is Associated with Low Red Blood Cell Omega-3 Fatty Acid Status and Inadequate Polyunsaturated Fatty Acid Dietary Intake. Pediatr. Obes. 2020, 15, e12689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soe, L.T.; Fahmida, U.; Seniati, A.N.L.; Firmansyah, A. Nutrients Essential for Cognitive Function Are Typical Problem Nutrients in the Diets of Myanmar Primary School Children: Findings of a Linear Programming Analysis. Food Nutr. Bull. 2020, 41, 211–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parasannanavar, D.; Gaddam, I.; Bukya, T.; Ibrahim, S.A.; Reddy, K.S.; Banjara, S.K.; Salvadi, B.P.P.; Kumar, B.N.; Rao, S.F.; Geddam, J.J.B.; et al. Omega-3 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acid Intake and Plasma Fatty Acids of School Going Indian Children—A Cross-Sectional Study. Prostaglandins Leukot. Essent. Fat. Acids 2021, 170, 102294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansen, E.C.; Conroy, D.A.; Burgess, H.J.; O’Brien, L.M.; Cantoral, A.; Téllez-Rojo, M.M.; Peterson, K.E.; Baylin, A. Plasma DHA Is Related to Sleep Timing and Duration in a Cohort of Mexican Adolescents. J. Nutr. 2020, 150, 592–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bascuñán, K.A.; Valenzuela, R.; Chamorro, R.; Valencia, A.; Barrera, C.; Puigrredon, C.; Sandoval, J.; Valenzuela, A. Polyunsaturated Fatty Acid Composition of Maternal Diet and Erythrocyte Phospholipid Status in Chilean Pregnant Women. Nutrients 2014, 6, 4918–4934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, V.W.S.; Ng, Y.F.; Chan, S.M.; Su, Y.X.; Kwok, K.W.H.; Chan, H.M.; Cheung, C.L.; Lee, H.W.; Pak, W.Y.; Li, S.Y.; et al. Positive Relationship between Consumption of Specific Fish Type and N-3 PUFA in Milk of Hong Kong Lactating Mothers. Br. J. Nutr. 2019, 121, 1431–1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chamorro, R.; Gonzalez, M.F.; Aliaga, R.; Gengler, V.; Balladares, C.; Barrera, C.; Bascuñan, K.A.; Bazinet, R.P.; Valenzuela, R. Diet, Plasma, Erythrocytes, and Spermatozoa Fatty Acid Composition Changes in Young Vegan Men. Lipids 2020, 55, 639–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hautero, U.; Poussa, T.; Laitinen, K. Simple Dietary Criteria to Improve Serum N-3 Fatty Acid Levels of Mothers and Their Infants. Public Health Nutr. 2017, 20, 534–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nikolajeva, K.; Aizbalte, O.; Rezgale, R.; Cauce, V.; Zacs, D.; Meija, L. The Intake of Omega-3 Fatty Acids, the Omega-3 Index in Pregnant Women, and Their Correlations with Gestational Length and Newborn Birth Weight. Nutrients 2024, 16, 2150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Souza Santos da Costa, R.; da Silva Santos, F.; de Barros Mucci, D.; de Souza, T.V.; de Carvalho Sardinha, F.L.; Moutinho de Miranda Chaves, C.R.; das Graças Tavares do Carmo, M. Trans Fatty Acids in Colostrum, Mature Milk and Diet of Lactating Adolescents. Lipids 2016, 51, 1363–1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hovinen, T.; Korkalo, L.; Freese, R.; Skaffari, E.; Isohanni, P.; Niemi, M.; Nevalainen, J.; Gylling, H.; Zamboni, N.; Erkkola, M.; et al. Vegan Diet in Young Children Remodels Metabolism and Challenges the Statuses of Essential Nutrients. EMBO Mol. Med. 2021, 13, e13492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.; Yang, Y.; Xu, F.; Ye, M.; Hu, P.; Jiang, W.; Li, F.; Fu, Y.; Xie, Z.; Zhu, Y.; et al. Association between Dietary Fatty Acid Patterns Based on Principal Component Analysis and Fatty Acid Compositions of Serum and Breast Milk in Lactating Mothers in Nanjing, China. Food Funct. 2021, 12, 8704–8714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vizzari, G.; Morniroli, D.; Alessandretti, F.; Galli, V.; Colombo, L.; Turolo, S.; Syren, M.L.; Pesenti, N.; Agostoni, C.; Mosca, F.; et al. Comparative Analysis of Docosahexaenoic Acid (DHA) Content in Mother’s Milk of Term and Preterm Mothers. Nutrients 2022, 14, 4595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, C.; Liu, G.; Whitfield, K.C.; Kroeun, H.; Green, T.J.; Gibson, R.A.; Makrides, M.; Zhou, S.J. Comparison of Human Milk Fatty Acid Composition of Women From Cambodia and Australia. J. Hum. Lact. 2018, 34, 585–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulder, K.A.; Dyer, R.A.; Elango, R.; Innis, S.M. Complexity of Understanding the Role of Dietary and Erythrocyte Docosahexaenoic Acid (DHA) on the Cognitive Performance of School-Age Children. Curr. Dev. Nutr. 2022, 6, nzac099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, M.T.T.; Kim, J.; Seo, N.; Lee, A.H.; Kim, Y.K.; Jung, J.A.; Li, D.; To, X.H.M.; Huynh, K.T.N.; Van Le, T.; et al. Comprehensive Analysis of Fatty Acids in Human Milk of Four Asian Countries. J. Dairy Sci. 2021, 104, 6496–6507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luxwolda, M.F.; Kuipers, R.S.; Rudy Boersma, E.; van Goor, S.A.; Janneke Dijck-Brouwer, D.A.; Bos, A.F.; Muskiet, F.A.J. DHA Status Is Positively Related to Motor Development in Breastfed African and Dutch Infants. Nutr. Neurosci. 2014, 17, 97–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chamorro, R.; Bascuñán, K.A.; Barrera, C.; Sandoval, J.; Puigrredon, C.; Valenzuela, R. Reduced N-3 and n-6 PUFA (DHA and AA) Concentrations in Breast Milk and Erythrocytes Phospholipids during Pregnancy and Lactation in Women with Obesity. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, H.S.; Barraza-Villarreal, A.; Biessy, C.; Duarte-Salles, T.; Sly, P.D.; Ramakrishnan, U.; Rivera, J.; Herceg, Z.; Romieu, I. Dietary Supplementation with Polyunsaturated Fatty Acid during Pregnancy Modulates DNA Methylation at IGF2/H19 Imprinted Genes and Growth of Infants. Physiol. Genom. 2014, 46, 851–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Figueroa-Garduño, I.; Escamilla-Núñez, C.; Barraza-Villarreal, A.; Hernández-Cadena, L.; Onofre-Pardo, E.N.; Romieu, I. Docosahexaenoic Acid Effect on Prenatal Exposure to Arsenic and Atopic Dermatitis in Mexican Preschoolers. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2023, 201, 3152–3161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez-Delgado, R.I.; Barraza-Villarreal, A.; Escamilla-Núñez, C.; Hernández-Cadena, L.; Garcia-Feregrino, R.; Shackleton, C.; Ramakrishnan, U.; Sly, P.D.; Romieu, I. Effect of Omega-Fatty Acids Supplementation during Pregnancy on Lung Function in Preschoolers: A Clinical Trial. J. Asthma 2019, 56, 296–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wimalasena, S.T.; Ramírez-Silva, C.I.; Gonzalez Casanova, I.; Stein, A.D.; Sun, Y.V.; Rivera, J.A.; Demmelmair, H.; Koletzko, B.; Ramakrishnan, U. Effects of Prenatal Docosahexaenoic Acid Supplementation on Offspring Cardiometabolic Health at 11 Years Differs by Maternal Single Nucleotide Polymorphism Rs174602: Follow-up of a Randomized Controlled Trial in Mexico. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2023, 118, 1123–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Rodriguez, C.E.; Olza, J.; Mesa, M.D.; Aguilera, C.M.; Miles, E.A.; Noakes, P.S.; Vlachava, M.; Kremmyda, L.S.; Diaper, N.D.; Godfrey, K.M.; et al. Fatty Acid Status and Antioxidant Defense System in Mothers and Their Newborns after Salmon Intake during Late Pregnancy. Nutrition 2017, 33, 157–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tandon, S.; Gonzalez-Casanova, I.; Barraza-Villarreal, A.; Romieu, I.; Demmelmair, H.; Jones, D.P.; Koletzko, B.; Stein, A.D.; Ramakrishnan, U. Infant Metabolome in Relation to Prenatal DHA Supplementation and Maternal Single-Nucleotide Polymorphism Rs174602: Secondary Analysis of a Randomized Controlled Trial in Mexico. J. Nutr. 2021, 151, 3339–3349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christifano, D.N.; Chollet-Hinton, L.; Hoyer, D.; Schmidt, A.; Gustafson, K.M. Intake of Eggs, Choline, Lutein, Zeaxanthin, and DHA during Pregnancy and Their Relationship to Fetal Neurodevelopment. Nutr. Neurosci. 2023, 26, 749–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramakrishnan, U.; Gonzalez-Casanova, I.; Schnaas, L.; DiGirolamo, A.; Quezada, A.D.; Pallo, B.C.; Hao, W.; Neufeld, L.M.; Rivera, J.A.; Stein, A.D.; et al. Prenatal Supplementation with DHA Improves Attention at 5 y of Age: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2016, 104, 1075–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Copp, K.; DeFranco, E.A.; Kleiman, J.; Rogers, L.K.; Morrow, A.L.; Valentine, C.J. Nutrition Support Team Guide to Maternal Diet for the Human-Milk-Fed Infant. Nutr. Clin. Pract. 2018, 33, 687–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Escamilla-Nuñez, M.C.; Barraza-Villarreal, A.; Hernańdez-Cadena, L.; Navarro-Olivos, E.; Sly, P.D.; Romieu, I. Omega-3 Fatty Acid Supplementation during Pregnancy and Respiratory Symptoms in Children. Chest 2014, 146, 373–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gázquez, A.; Uhl, O.; Ruíz-Palacios, M.; Gill, C.; Patel, N.; Koletzko, B.; Poston, L.; Larqué, E. Placental Lipid Droplet Composition: Effect of a Lifestyle Intervention (UPBEAT) in Obese Pregnant Women. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Cell Biol. Lipids 2018, 1863, 998–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramakrishnan, U.; Stinger, A.; Digirolamo, A.M.; Martorell, R.; Neufeld, L.M.; Rivera, J.A.; Schnaas, L.; Stein, A.D.; Wang, M. Prenatal Docosahexaenoic Acid Supplementation and Offspring Development at 18 Months: Randomized Controlled Trial. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0120065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutierrez-Gomez, Y.; Stein, A.D.; Ramakrishnan, U.; Barraza-Villarreal, A.; Moreno-Macias, H.; Aguilar-Salinas, C.; Romieu, I.; Rivera, J.A. Prenatal Docosahexaenoic Acid Supplementation Does Not Affect Nonfasting Serum Lipid and Glucose Concentrations of Offspring at 4 Years of Age in a Follow-up of a Randomized Controlled Clinical Trial in Mexico. J. Nutr. 2017, 147, 242–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demmelmair, H.; Øyen, J.; Pickert, T.; Rauh-Pfeiffer, A.; Stormark, K.M.; Graff, I.E.; Lie, Ø.; Kjellevold, M.; Koletzko, B. The Effect of Atlantic Salmon Consumption on the Cognitive Performance of Preschool Children—A Randomized Controlled Trial. Clin. Nutr. 2019, 38, 2558–2568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Casanova, I.; Rzehak, P.; Stein, A.D.; Feregrino, R.G.; Dommarco, J.A.R.; Barraza-Villarreal, A.; Demmelmair, H.; Romieu, I.; Villalpando, S.; Martorell, R.; et al. Maternal Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms in the Fatty Acid Desaturase 1 and 2 Coding Regions Modify the Impact of Prenatal Supplementation with DHA on Birth Weight. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2016, 103, 1171–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonzalez Casanova, I.; Schoen, M.; Tandon, S.; Stein, A.D.; Barraza Villarreal, A.; DiGirolamo, A.M.; Demmelmair, H.; Ramirez Silva, I.; Feregrino, R.G.; Rzehak, P.; et al. Maternal FADS2 Single Nucleotide Polymorphism Modified the Impact of Prenatal Docosahexaenoic Acid (DHA) Supplementation on Child Neurodevelopment at 5 Years: Follow-up of a Randomized Clinical Trial. Clin. Nutr. 2021, 40, 5339–5345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stonehouse, W. Does Consumption of LC Omega-3 PUFA Enhance Cognitive Performance in Healthy School-Aged Children and throughout Adulthood? Evidence from Clinical Trials. Nutrients 2014, 6, 2730–2758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunnane, S.C.; Crawford, M.A. Energetic and Nutritional Constraints on Infant Brain Development: Implications for Brain Expansion during Human Evolution. J. Hum. Evol. 2014, 77, 88–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delplanque, B.; Gibson, R.; Koletzko, B.; Lapillonne, A.; Strandvik, B. Lipid Quality in Infant Nutrition: Current Knowledge and Future Opportunities. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2015, 61, 8–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Matos Reis, Á.E.; Teixeira, I.S.; Maia, J.M.; Luciano, L.A.A.; Brandião, L.M.; Silva, M.L.S.; Branco, L.G.S.; Soriano, R.N. Maternal Nutrition and Its Effects on Fetal Neurodevelopment. Nutrition 2024, 125, 112483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cetin, I.; Carlson, S.E.; Burden, C.; da Fonseca, E.B.; di Renzo, G.C.; Hadjipanayis, A.; Harris, W.S.; Kumar, K.R.; Olsen, S.F.; Mader, S.; et al. Omega-3 Fatty Acid Supply in Pregnancy for Risk Reduction of Preterm and Early Preterm Birth. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. MFM 2024, 6, 101251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martins, B.P.; Bandarra, N.M.; Figueiredo-Braga, M. The Role of Marine Omega-3 in Human Neurodevelopment, Including Autism Spectrum Disorders and Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder–a Review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2020, 60, 1431–1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zielinska, M.A.; Hamulka, J.; Grabowicz-Chadrzyńska, I.; Bryś, J.; Wesolowska, A. Association between Breastmilk LC PUFA, Carotenoids and Psychomotor Development of Exclusively Breastfed Infants. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, W.L.; Bernard, J.Y.; Armand, M.; Sarté, C.; Charles, M.A.; Heude, B. Associations of Maternal Consumption of Dairy Products during Pregnancy with Perinatal Fatty Acids Profile in the EDEN Cohort Study. Nutrients 2022, 14, 1636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nishimura, R.Y.; Barbieiri, P.; de Castro, G.S.F.; Jordão, A.A.; da Silva Castro Perdoná, G.; Sartorelli, D.S. Dietary Polyunsaturated Fatty Acid Intake during Late Pregnancy Affects Fatty Acid Composition of Mature Breast Milk. Nutrition 2014, 30, 685–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahreynian, M.; Feizi, A.; Daniali, S.S.; Kelishadi, R. Interaction between Maternal Dietary Fat Intake, Breast Milk Omega-3 Fatty Acids and Infant Growth during the First Year of Life. Child Care Health Dev. 2023, 49, 137–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogaz-González, R.; Mérida-Ortega, Á.; Torres-Sánchez, L.; Schnaas, L.; Hernández-Alcaraz, C.; Cebrián, M.E.; Rothenberg, S.J.; García-Hernández, R.M.; López-Carrillo, L. Maternal Dietary Intake of Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids Modifies Association between Prenatal DDT Exposure and Child Neurodevelopment: A Cohort Study. Environ. Pollut. 2018, 238, 698–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakola, L.; Takkinen, H.M.; Niinistö, S.; Ahonen, S.; Erlund, I.; Rautanen, J.; Veijola, R.; Ilonen, J.; Toppari, J.; Knip, M.; et al. Maternal Fatty Acid Intake during Pregnancy and the Development of Childhood Overweight: A Birth Cohort Study. Pediatr. Obes. 2017, 12, 26–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Hinai, M.; Baylin, A.; Tellez-Rojo, M.M.; Cantoral, A.; Ettinger, A.; Solano-González, M.; Peterson, K.E.; Perng, W. Maternal Intake of Omega-3 and Omega-6 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids during Mid-Pregnancy Is Inversely Associated with Linear Growth. J. Dev. Orig. Health Dis. 2018, 9, 432–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kortman, G.A.M.; Timmerman, H.M.; Schaafsma, A.; Stoutjesdijk, E.; Muskiet, F.A.J.; Nhien, N.V.; van Hoffen, E.; Boekhorst, J.; Nauta, A. Mothers’ Breast Milk Composition and Their Respective Infant’s Gut Microbiota Differ between Five Distinct Rural and Urban Regions in Vietnam. Nutrients 2023, 15, 4802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barrera, C.; Valenzuela, R.; Chamorro, R.; Bascuñán, K.; Sandoval, J.; Sabag, N.; Valenzuela, F.; Valencia, M.P.; Puigrredon, C.; Valenzuela, A. The Impact of Maternal Diet during Pregnancy and Lactation on the Fatty Acid Composition of Erythrocytes and Breast Milk of Chilean Women. Nutrients 2018, 10, 839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crozier, S.R.; Godfrey, K.M.; Calder, P.C.; Robinson, S.M.; Inskip, H.M.; Baird, J.; Gale, C.R.; Cooper, C.; Sibbons, C.M.; Fisk, H.L.; et al. Vegetarian Diet during Pregnancy Is Not Associated with Poorer Cognitive Performance in Children at Age 6–7 Years. Nutrients 2019, 11, 3029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gershuni, V.; Li, Y.; Elovitz, M.; Li, H.; Wu, G.D.; Compher, C.W. Maternal Gut Microbiota Reflecting Poor Diet Quality Is Associated with Spontaneous Preterm Birth in a Prospective Cohort Study. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2021, 113, 602–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falize, C.; Savage, M.; Jeanes, Y.M.; Dyall, S.C. Evaluating the Relationship between the Nutrient Intake of Lactating Women and Their Breast Milk Nutritional Profile: A Systematic Review and Narrative Synthesis. Br. J. Nutr. 2024, 131, 1196–1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bravi, F.; Wiens, F.; Decarli, A.; Dal Pont, A.; Agostoni, C.; Ferraroni, M. Impact of Maternal Nutrition on Breast-Milk Composition: A Systematic Review. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2016, 104, 646–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petersohn, I.; Hellinga, A.H.; van Lee, L.; Keukens, N.; Bont, L.; Hettinga, K.A.; Feskens, E.J.M.; Brouwer-Brolsma, E.M. Maternal Diet and Human Milk Composition: An Updated Systematic Review. Front. Nutr. 2023, 10, 1320560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- English, L.; Obbagy, J.; Wong, Y.P.; Psota, T.; Nadaud, P.; Johns, K.; Terry, N.; Butte, N.; Dewey, K.; Fleischer, D.; et al. Types and Amounts of Complementary Foods and Beverages Consumed and Developmental Milestones: A Systematic Review. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2019, 109, 956S–977S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forsyth, S.; Gautier, S.; Salem, N. Global Estimates of Dietary Intake of Docosahexaenoic Acid and Arachidonic Acid in Developing and Developed Countries. Ann. Nutr. Metab. 2016, 68, 258–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lassek, W.D.; Gaulin, S.J.C. Maternal Milk DHA Content Predicts Cognitive Performance in a Sample of 28 Nations. Matern. Child Nutr. 2015, 11, 773–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lassek, W.D.; Gaulin, S.J.C. Linoleic and Docosahexaenoic Acids in Human Milk Have Opposite Relationships with Cognitive Test Performance in a Sample of 28 Countries. Prostaglandins Leukot. Essent. Fat. Acids 2014, 91, 195–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- FAO. Food balance Sheets 2010–2022—Global, Regional and Country Trends; FAOSTAT Analytical Briefs, No. 91; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Gobbo, L.C.; Khatibzadeh, S.; Imamura, F.; Micha, R.; Shi, P.; Smith, M.; Myers, S.S.; Mozaffarian, D. Assessing Global Dietary Habits: A Comparison of National Estimates from the FAO and the Global Dietary Database. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2015, 101, 1038–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture 2022. Towards Blue Transformation; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Burdge, G.C.; Tan, S.-Y.; Henry, C.J. Long-Chain n -3 PUFA in Vegetarian Women: A Metabolic Perspective. J. Nutr. Sci. 2017, 6, e58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Valle-Valdez, B.; Terrazas-Lopez, X.; Gonzalez-Rocha, A.; Astiazaran-Garcia, H.; Armenta-Guirado, B. Dietary Patterns of Docosahexaenoic Acid Intake and Supplementation from Pregnancy Through Childhood with a Focus on Low- and Middle-Income Countries: A Narrative Review of Implications for Child Health. Nutrients 2025, 17, 3931. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17243931

Valle-Valdez B, Terrazas-Lopez X, Gonzalez-Rocha A, Astiazaran-Garcia H, Armenta-Guirado B. Dietary Patterns of Docosahexaenoic Acid Intake and Supplementation from Pregnancy Through Childhood with a Focus on Low- and Middle-Income Countries: A Narrative Review of Implications for Child Health. Nutrients. 2025; 17(24):3931. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17243931

Chicago/Turabian StyleValle-Valdez, Brenda, Xochitl Terrazas-Lopez, Alejandra Gonzalez-Rocha, Humberto Astiazaran-Garcia, and Brianda Armenta-Guirado. 2025. "Dietary Patterns of Docosahexaenoic Acid Intake and Supplementation from Pregnancy Through Childhood with a Focus on Low- and Middle-Income Countries: A Narrative Review of Implications for Child Health" Nutrients 17, no. 24: 3931. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17243931

APA StyleValle-Valdez, B., Terrazas-Lopez, X., Gonzalez-Rocha, A., Astiazaran-Garcia, H., & Armenta-Guirado, B. (2025). Dietary Patterns of Docosahexaenoic Acid Intake and Supplementation from Pregnancy Through Childhood with a Focus on Low- and Middle-Income Countries: A Narrative Review of Implications for Child Health. Nutrients, 17(24), 3931. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17243931