Discovering Anticancer Effects of Phytochemicals on MicroRNA in the Context of Data Mining

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cell Culture

2.2. Cell Proliferation Assay

2.3. DNA Library Construction and Sequencing Analysis for miRNA

2.4. Compound Prediction Using IBM Watson for Drug Discovery

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

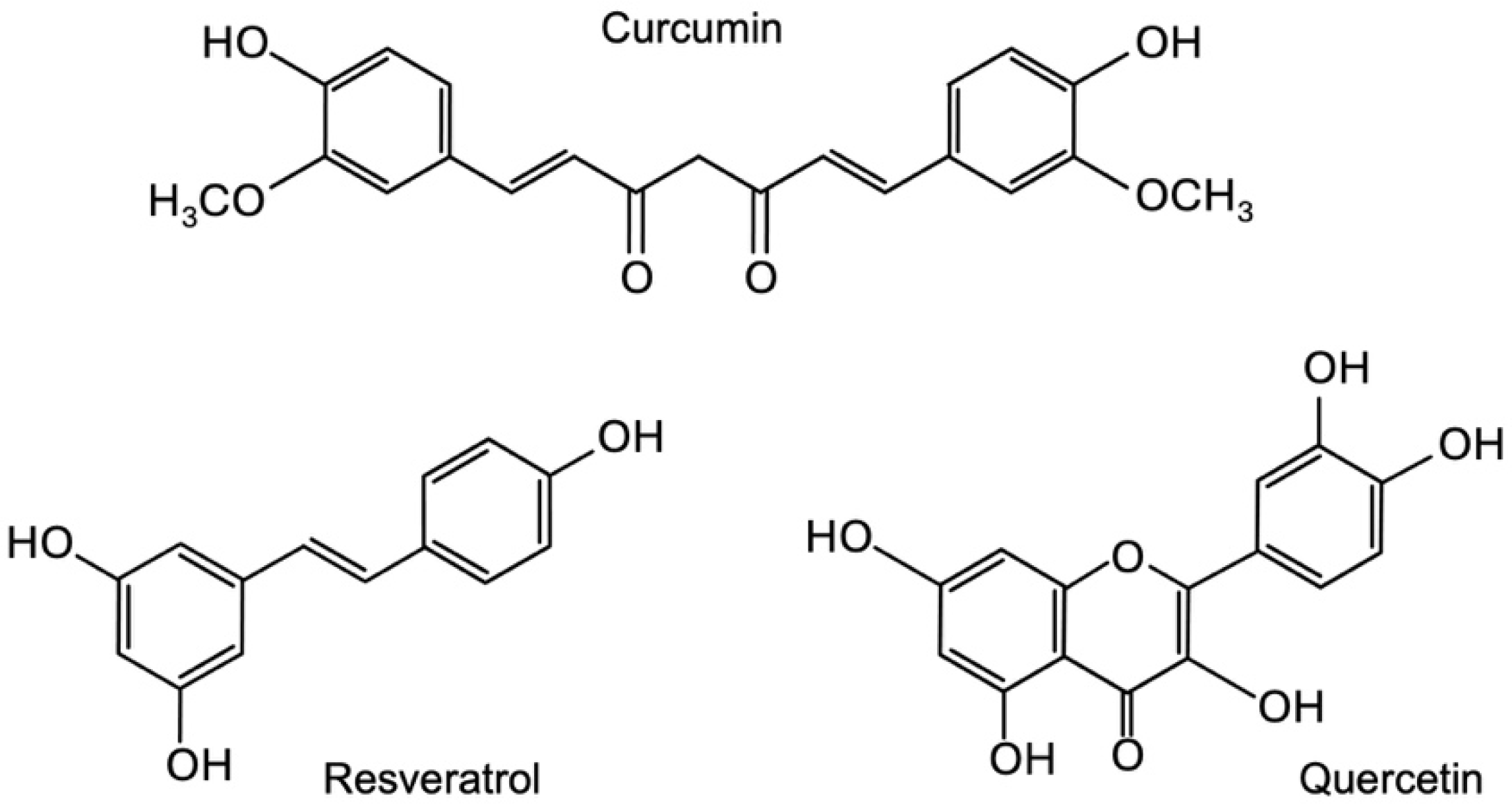

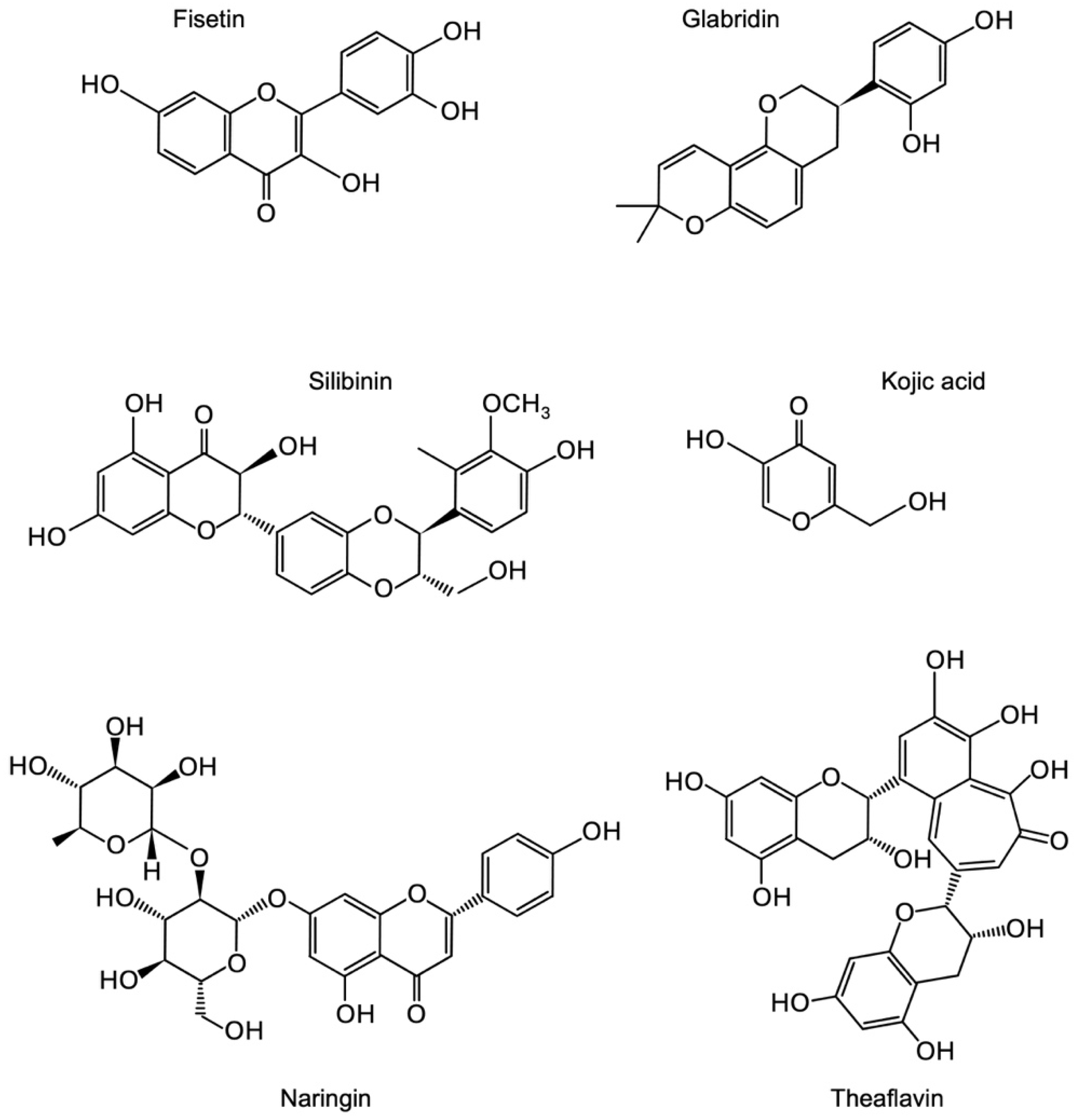

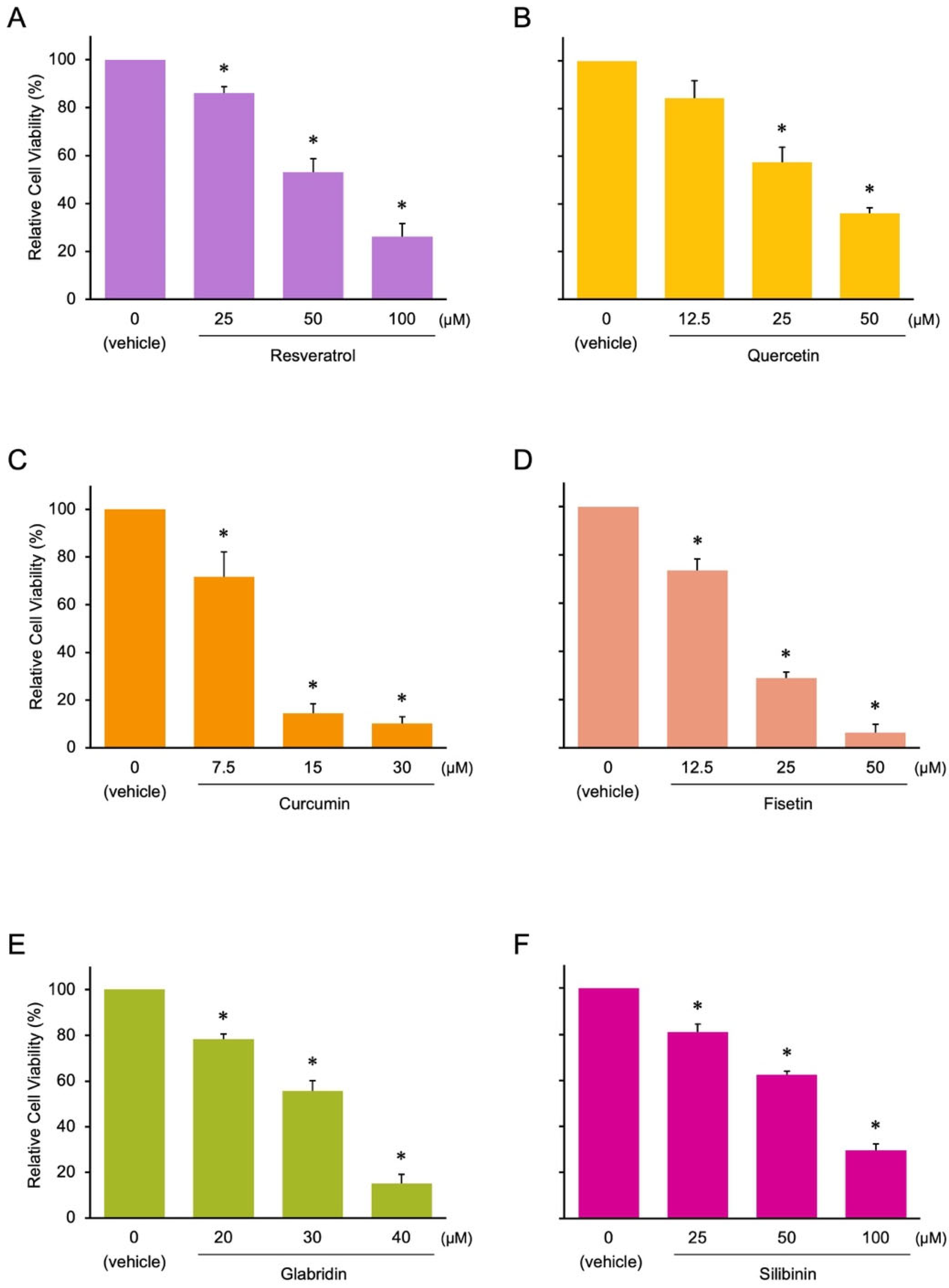

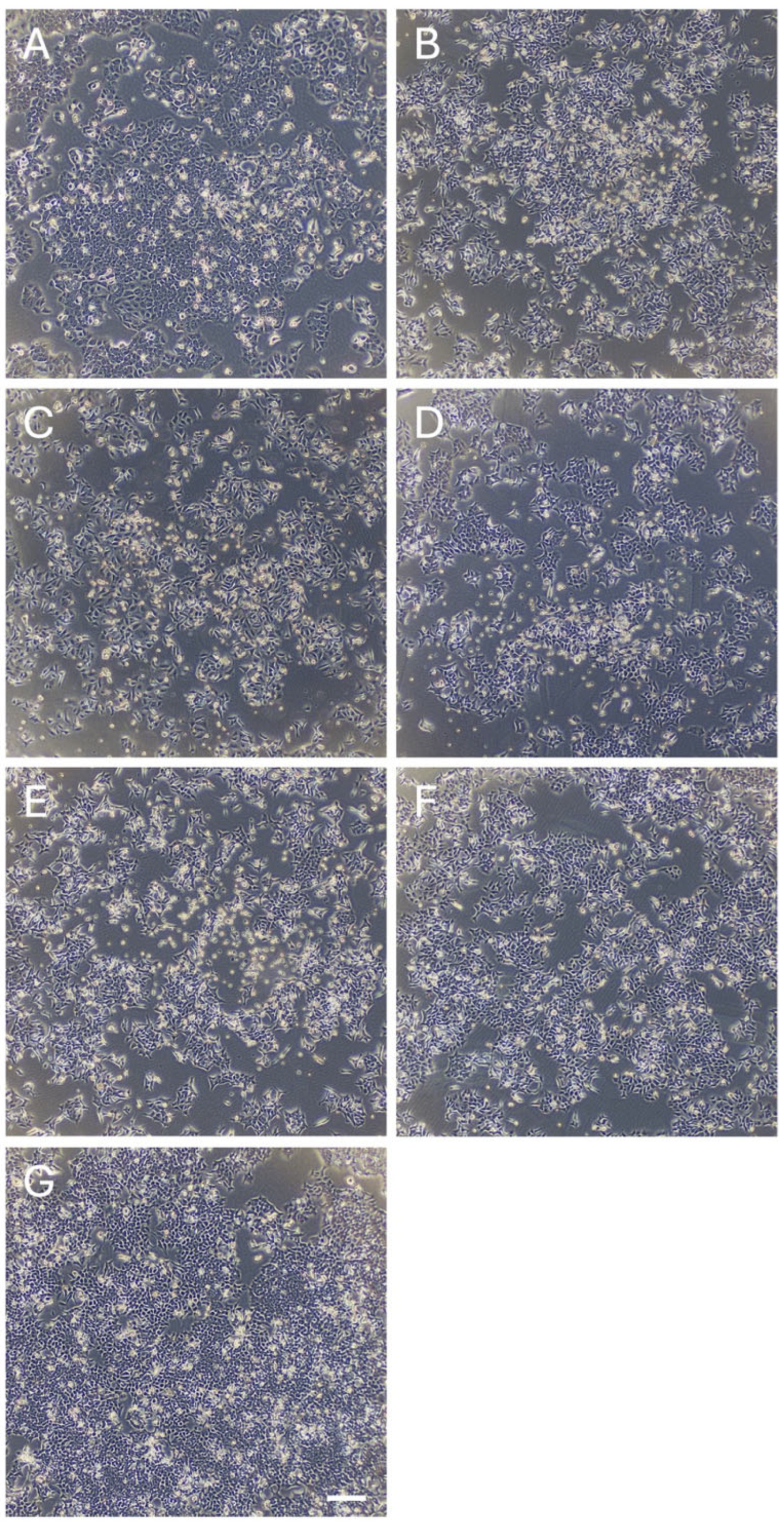

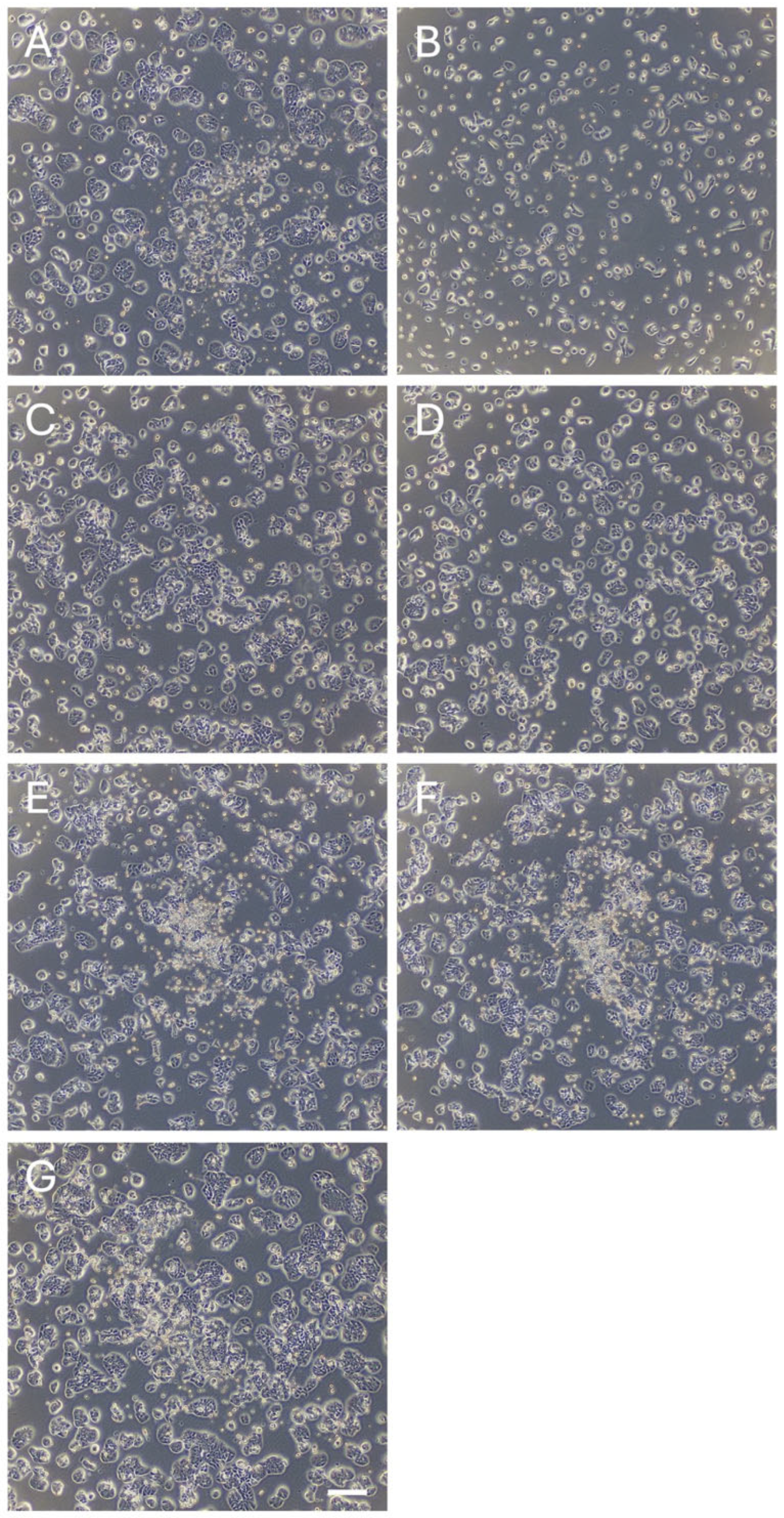

3.1. Identification of Novel Phytochemicals: Candidates for Controlling Cell Proliferation in Colon Cancer

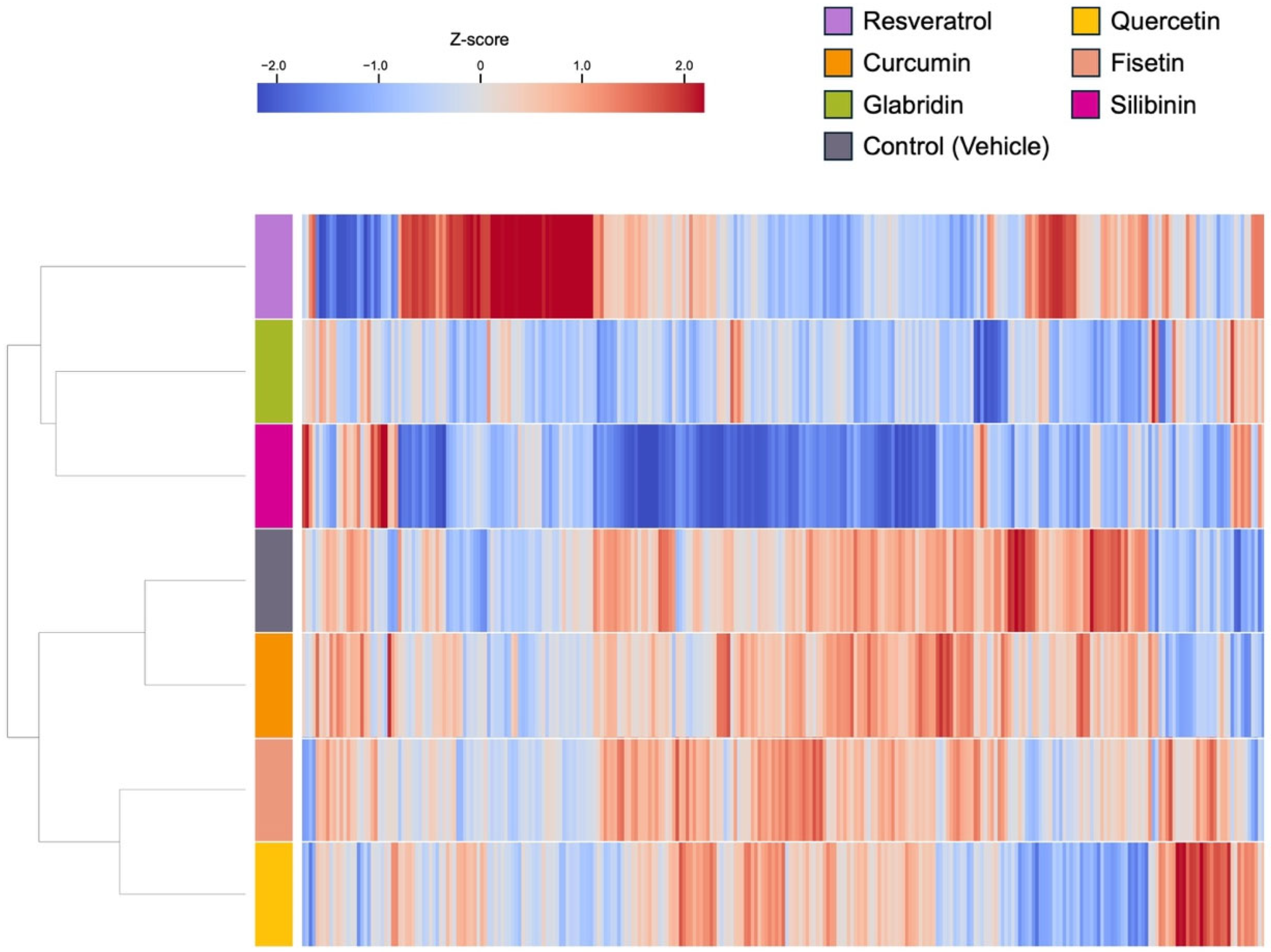

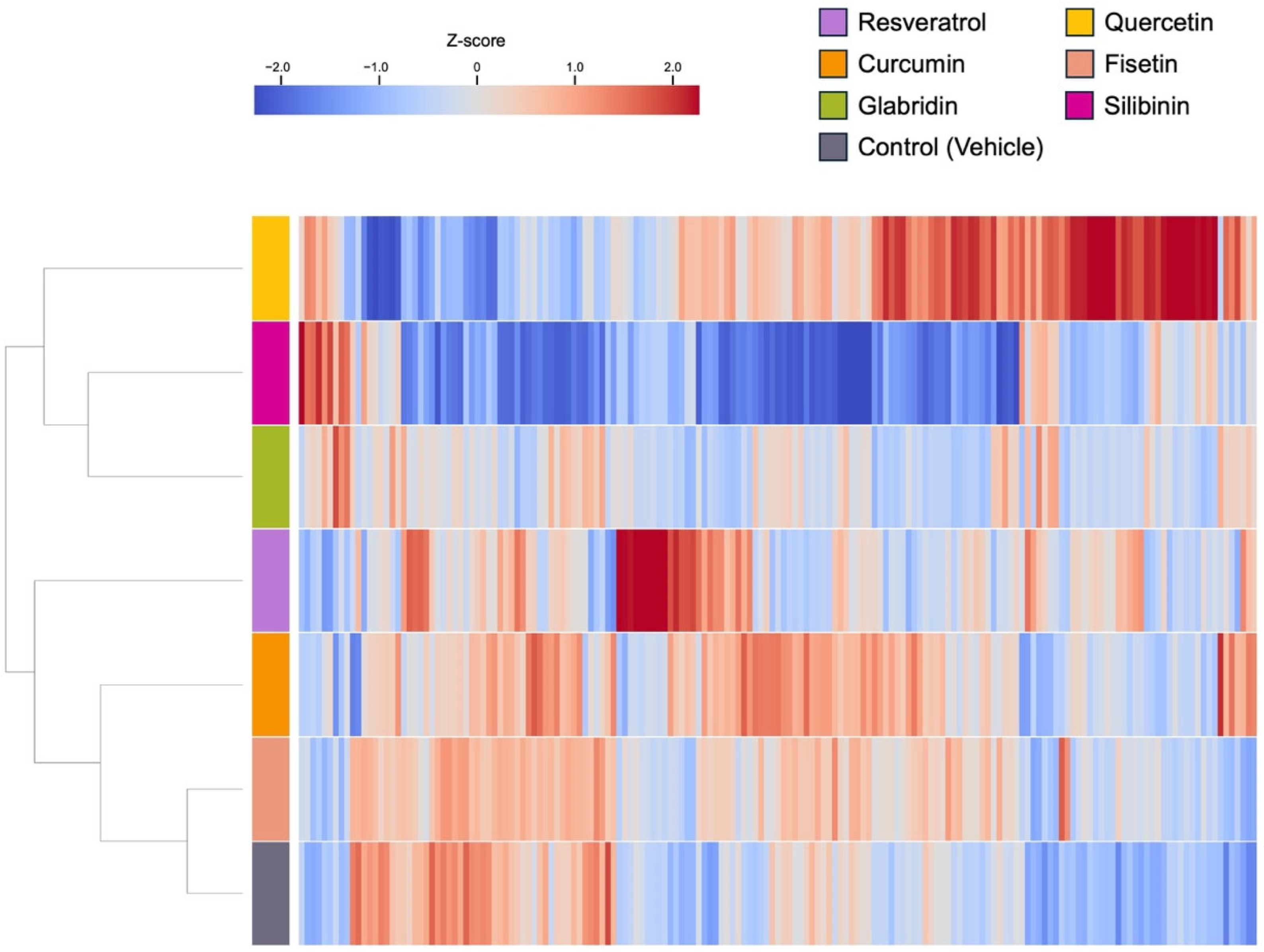

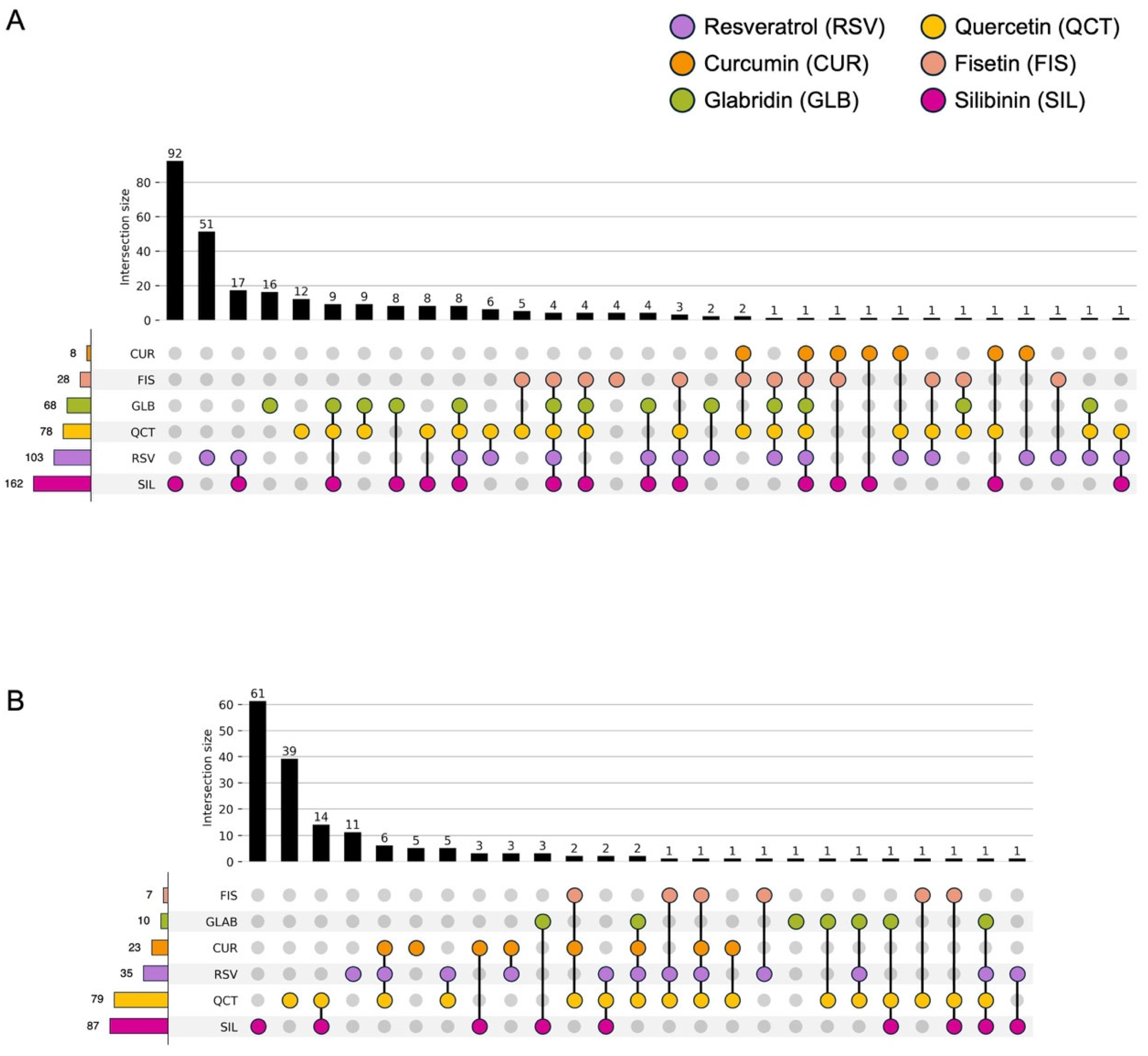

3.2. Effects of the Phytochemicals on Modulating miRNA Expression

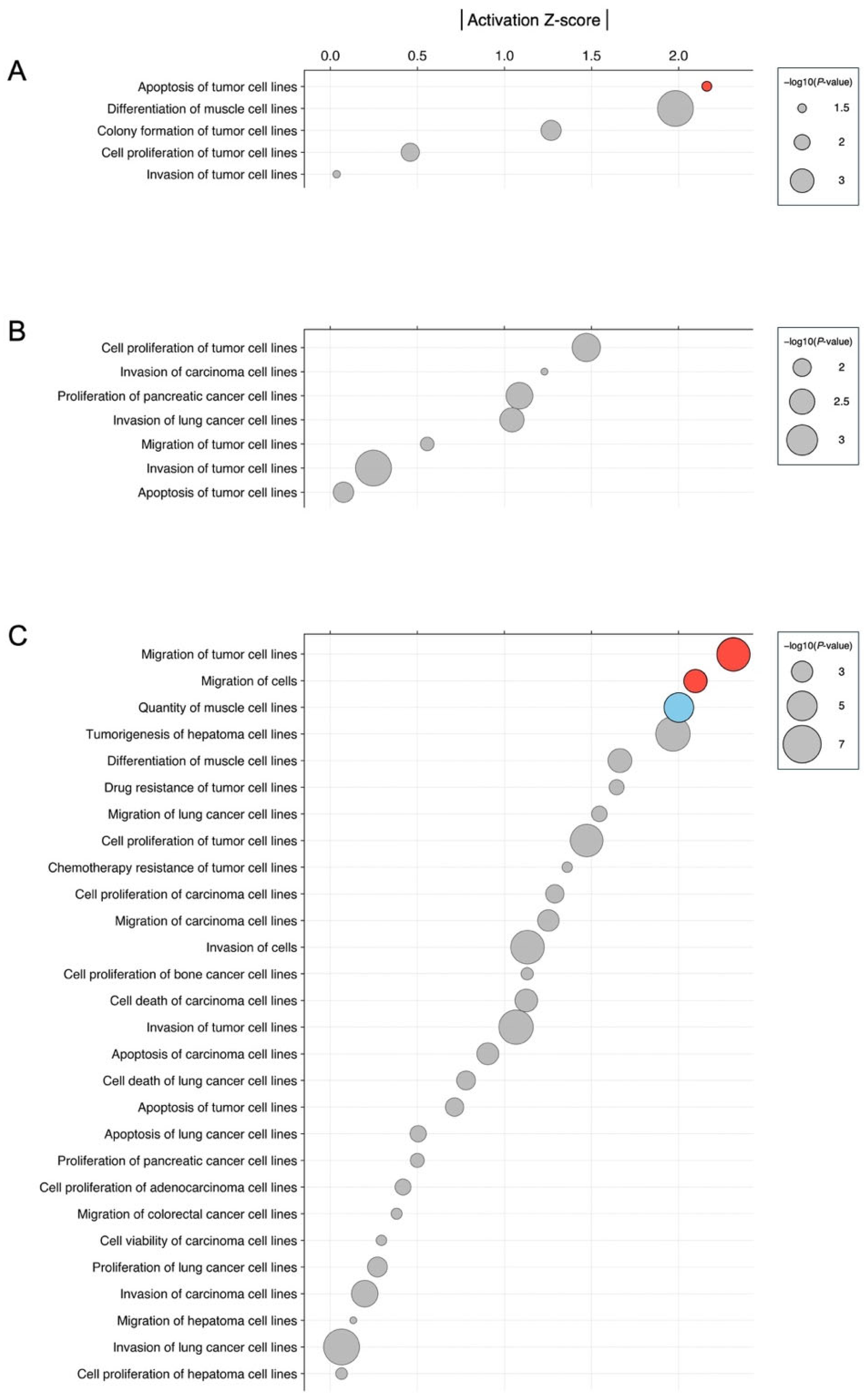

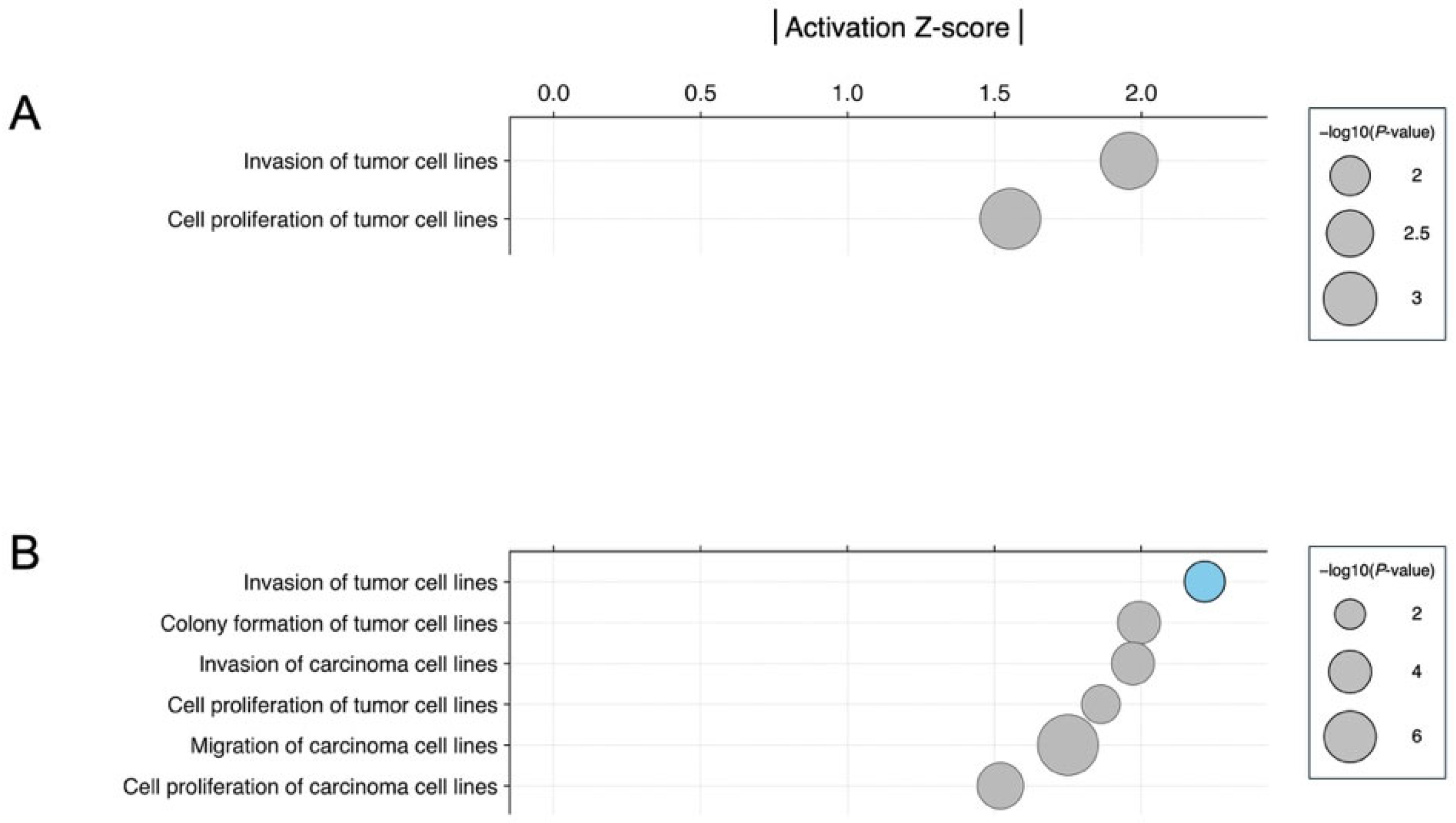

3.3. Biological Significance of miRNA Signatures in Each Phytochemical Treatment: Pathway Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Key, T.J. Fruit and vegetables and cancer risk. Br. J. Cancer 2011, 104, 6–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slavin, J.L.; Lloyd, B. Health benefits of fruits and vegetables. Adv. Nutr. 2012, 3, 506–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Ouyang, Y.; Liu, J.; Zhu, M.; Zhao, G.; Bao, W.; Hu, F.B. Fruit and vegetable consumption and mortality from all causes, cardiovascular disease, and cancer: Systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. BMJ 2014, 349, g4490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otsuka, K.; Nishiyama, H.; Kuriki, D.; Kawada, N.; Ochiya, T. Connecting the dots in the associations between diet, obesity, cancer, and microRNAs. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2023, 93, 52–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clinton, S.K.; Giovannucci, E.L.; Hursting, S.D. The World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute for Cancer Research Third Expert Report on Diet, Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Cancer: Impact and Future Directions. J. Nutr. 2020, 150, 663–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Otsuka, K.; Yamamoto, Y.; Matsuoka, R.; Ochiya, T. Maintaining good miRNAs in the body keeps the doctor away?: Perspectives on the relationship between food-derived natural products and microRNAs in relation to exosomes/extracellular vesicles. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2018, 62, 1700080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Catalgol, B.; Batirel, S.; Taga, Y.; Ozer, N.K. Resveratrol: French paradox revisited. Front. Pharmacol. 2012, 3, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gebert, L.F.R.; MacRae, I.J. Regulation of microRNA function in animals. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2019, 20, 21–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calin, G.A.; Croce, C.M. MicroRNA signatures in human cancers. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2006, 6, 857–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otsuka, K.; Ochiya, T. Possible connection between diet and microRNA in cancer scenario. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2021, 73, 4–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuzaki, J.; Kato, K.; Oono, K.; Tsuchiya, N.; Sudo, K.; Shimomura, A.; Tamura, K.; Shiino, S.; Kinoshita, T.; Daiko, H.; et al. Prediction of tissue-of-origin of early stage cancers using serum miRNomes. JNCI Cancer Spectr. 2023, 7, pkac080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuzaki, J.; Ochiya, T. Circulating microRNAs and extracellular vesicles as potential cancer biomarkers: A systematic review. Int. J. Clin. Oncol. 2017, 22, 413–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otsuka, K.; Ochiya, T. Comparative analysis of the effect of resveratrol derivatives on microRNAs. Food Sci. Technol. Res. 2024, 30, 697–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Elenee Argentinis, J.D.; Weber, G. IBM Watson: How Cognitive Computing Can Be Applied to Big Data Challenges in Life Sciences Research. Clin. Ther. 2016, 38, 688–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakkar, N.; Kovalik, T.; Lorenzini, I.; Spangler, S.; Lacoste, A.; Sponaugle, K.; Ferrante, P.; Argentinis, E.; Sattler, R.; Bowser, R. Artificial intelligence in neurodegenerative disease research: Use of IBM Watson to identify additional RNA-binding proteins altered in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Acta Neuropathol. 2018, 135, 227–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, Y.; Croce, C.M. The role of MicroRNAs in human cancer. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2016, 1, 15004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Keefe, S.J. Diet, microorganisms and their metabolites, and colon cancer. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2016, 13, 691–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shabbir, U.; Rubab, M.; Daliri, E.B.; Chelliah, R.; Javed, A.; Oh, D.H. Curcumin, Quercetin, Catechins and Metabolic Diseases: The Role of Gut Microbiota. Nutrients 2021, 13, 206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akimoto, N.; Ugai, T.; Zhong, R.; Hamada, T.; Fujiyoshi, K.; Giannakis, M.; Wu, K.; Cao, Y.; Ng, K.; Ogino, S. Rising incidence of early-onset colorectal cancer—A call to action. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2021, 18, 230–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veettil, S.K.; Wong, T.Y.; Loo, Y.S.; Playdon, M.C.; Lai, N.M.; Giovannucci, E.L.; Chaiyakunapruk, N. Role of Diet in Colorectal Cancer Incidence: Umbrella Review of Meta-analyses of Prospective Observational Studies. JAMA Netw. Open 2021, 4, e2037341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papier, K.; Bradbury, K.E.; Balkwill, A.; Barnes, I.; Smith-Byrne, K.; Gunter, M.J.; Berndt, S.I.; Le Marchand, L.; Wu, A.H.; Peters, U.; et al. Diet-wide analyses for risk of colorectal cancer: Prospective study of 12,251 incident cases among 542,778 women in the UK. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagiwara, K.; Kosaka, N.; Yoshioka, Y.; Takahashi, R.U.; Takeshita, F.; Ochiya, T. Stilbene derivatives promote Ago2-dependent tumour-suppressive microRNA activity. Sci. Rep. 2012, 2, 314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Otsuka, K.; Yamamoto, Y.; Ochiya, T. Regulatory role of resveratrol, a microRNA-controlling compound, in HNRNPA1 expression, which is associated with poor prognosis in breast cancer. Oncotarget 2018, 9, 24718–24730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kramer, A.; Green, J.; Pollard, J., Jr.; Tugendreich, S. Causal analysis approaches in Ingenuity Pathway Analysis. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 523–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sticht, C.; De La Torre, C.; Parveen, A.; Gretz, N. miRWalk: An online resource for prediction of microRNA binding sites. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0206239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derynck, R.; Turley, S.J.; Akhurst, R.J. TGFbeta biology in cancer progression and immunotherapy. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2021, 18, 9–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bray, F.; Laversanne, M.; Weiderpass, E.; Soerjomataram, I. The ever-increasing importance of cancer as a leading cause of premature death worldwide. Cancer 2021, 127, 3029–3030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bray, F.; Laversanne, M.; Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2024, 74, 229–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Fu, T.; Du, Y.; Gao, W.; Huang, K.; Liu, Z.; Chandak, P.; Liu, S.; Van Katwyk, P.; Deac, A.; et al. Scientific discovery in the age of artificial intelligence. Nature 2023, 620, 47–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrucci, D.; Brown, E.; Chu-Carroll, J.; Fan, J.; Gondek, D.; Kalyanpur, A.A.; Lally, A.; Murdock, J.W.; Nyberg, E.; Prager, J.; et al. Building Watson: An Overview of the DeepQA Project. AI Mag. 2010, 31, 59–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szymczak, J.; Cielecka-Piontek, J. Fisetin-In Search of Better Bioavailability-From Macro to Nano Modifications: A Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 14158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tavenier, J.; Nehlin, J.O.; Houlind, M.B.; Rasmussen, L.J.; Tchkonia, T.; Kirkland, J.L.; Andersen, O.; Rasmussen, L.J.H. Fisetin as a senotherapeutic agent: Evidence and perspectives for age-related diseases. Mech. Ageing Dev. 2024, 222, 111995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zamanian, M.Y.; Taheri, N.; Ramadan, M.F.; Mustafa, Y.F.; Alkhayyat, S.; Sergeevna, K.N.; Alsaab, H.O.; Hjazi, A.; Molavi Vasei, F.; Daneshvar, S. A comprehensive view on the fisetin impact on colorectal cancer in animal models: Focusing on cellular and molecular mechanisms. Anim. Model. Exp. Med. 2024, 7, 591–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- AlDehlawi, H.; Jazzar, A. The Power of Licorice (Radix glycyrrhizae) to Improve Oral Health: A Comprehensive Review of Its Pharmacological Properties and Clinical Implications. Healthcare 2023, 11, 2887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, C.W.; Gibbons, N.; Johnson, D.W.; Nicol, D.L. Silibinin—A promising new treatment for cancer. Anti-Cancer Agents Med. Chem. 2010, 10, 186–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, S.D.; Mendonca, P.; Kaur, S.; Soliman, K.F.A. Silibinin Anticancer Effects Through the Modulation of the Tumor Immune Microenvironment in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 6265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, W.; Yang, X.; Wang, Y.; Hou, G.; Wang, D.; Han, B.; Zhang, Y. The antitumor mechanisms of glabridin and drug delivery strategies for enhancing its bioavailability. Front. Oncol. 2024, 14, 1506588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roca, E.; Colloca, G.; Lombardo, F.; Bellieni, A.; Cucinella, A.; Madonia, G.; Martinelli, L.; Damiani, M.E.; Zampieri, I.; Santo, A. The importance of integrated therapies on cancer: Silibinin, an old and new molecule. Oncotarget 2024, 15, 345–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, P.P.; Islam, M.A.; Islam, M.S.; Han, A.; Geng, P.; Aziz, M.A.; Mamun, A.A. A comprehensive evaluation of the therapeutic potential of silibinin: A ray of hope in cancer treatment. Front. Pharmacol. 2024, 15, 1349745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zadeh, M.M.; Motamed, N.; Ranji, N.; Majidi, M.; Falahi, F. Silibinin-Induced Apoptosis and Downregulation of MicroRNA-21 and MicroRNA-155 in MCF-7 Human Breast Cancer Cells. J. Breast Cancer 2016, 19, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karami Fath, M.; Vakilinezami, P.; Abdoli Keleshtery, Z.; Sima Azgomi, Z.; Nezamivand Chegini, S.; Shahriarinour, M.; Seyfizadeh Saraabestani, S.; Diyarkojouri, M.; Nikpassand, M.; Ranji, N. Silibinin-Loaded Nanoparticles for Drug Delivery in Gastric Cancer: In Vitro Modulating miR-181a and miR-34a to Inhibit Cancer Cell Growth and Migration. Food Sci. Nutr. 2025, 13, e4609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranapour, S.; Motamed, N. Effect of Silibinin on the Expression of Mir-20b, Bcl2L11, and Erbb2 in Breast Cancer Cell Lines. Mol. Biotechnol. 2023, 65, 1979–1990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, F.; Mu, J.; Wang, X.; Ye, X.; Si, L.; Ning, S.; Li, Z.; Li, Y. The repressive effect of miR-148a on TGF beta-SMADs signal pathway is involved in the glabridin-induced inhibition of the cancer stem cells-like properties in hepatocellular carcinoma cells. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e96698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, F.; Li, Y.; Mu, J.; Hu, C.; Zhou, M.; Wang, X.; Si, L.; Ning, S.; Li, Z. Glabridin inhibits cancer stem cell-like properties of human breast cancer cells: An epigenetic regulation of miR-148a/SMAd2 signaling. Mol. Carcinog. 2016, 55, 929–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, J.; Zhu, D.; Shen, Z.; Ning, S.; Liu, Y.; Chen, J.; Li, Y.; Li, Z. The repressive effect of miR-148a on Wnt/beta-catenin signaling involved in Glabridin-induced anti-angiogenesis in human breast cancer cells. BMC Cancer 2017, 17, 307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, X.; Wang, S.; Song, Z.; Bao, Y.; Zheng, L.; Wang, G.; Sun, Y. miR-3929 Inhibits Proliferation and Promotes Apoptosis by Downregulating Cripto-1 Expression in Cervical Cancer Cells. Cytogenet. Genome Res. 2021, 161, 425–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, F.; Yang, H.; Kong, T.; Chen, S.; Li, P.; Chen, L.; Cheng, J.; Cui, G.; Zhang, G. PGAM1, regulated by miR-3614-5p, functions as an oncogene by activating transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-beta) signaling in the progression of non-small cell lung carcinoma. Cell Death Dis. 2020, 11, 710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, H.; Zhou, X.; Zhou, A.; Chen, J.; Chen, G.; Shi, X.; Shi, B.; Tai, Q.; Mi, X.; Zhou, G.; et al. RFC5, regulated by circ_0038985/miR-3614-5p, functions as an oncogene in the progression of colorectal cancer. Mol. Carcinog. 2023, 62, 771–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, J.; Zhang, D. Periplocin has anti-tumor actions in prostate cancer through modulating the miR-3614-5p/SLC4A4 axis. Pak. J. Pharm. Sci. 2025, 38, 1309–1320. [Google Scholar]

- Han, L.; Sun, Y.; Lu, C.; Ma, C.; Shi, J.; Sun, D. MiR-3614-5p Is a Potential Novel Biomarker for Colorectal Cancer. Front. Genet. 2021, 12, 666833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatadri, R.; Muni, T.; Iyer, A.K.; Yakisich, J.S.; Azad, N. Role of apoptosis-related miRNAs in resveratrol-induced breast cancer cell death. Cell Death Dis. 2016, 7, e2104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, Z.J.; Zhang, Z.G.; Hu, A.X.; Yang, F.; Gai, Y. miR-122-5p inhibits tumor cell proliferation and induces apoptosis by targeting MYC in gastric cancer cells. Pharmazie 2017, 72, 344–347. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, X.; Gao, F.; Wang, J.; Tao, L.; Ye, J.; Ding, L.; Ji, W.; Chen, X. MiR-122-5p inhibits cell migration and invasion in gastric cancer by down-regulating DUSP4. Cancer Biol. Ther. 2018, 19, 427–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, J.; Li, T.; Han, X.; Yuan, H. Knockdown of LncRNA ANRIL suppresses cell proliferation, metastasis, and invasion via regulating miR-122-5p expression in hepatocellular carcinoma. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2018, 144, 205–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Ma, T.; Chen, S.; Shi, N.; Zou, Y.; Hou, B.; Zhang, C. Down-regulated lncRNA SBF2-AS1 in M2 macrophage-derived exosomes elevates miR-122-5p to restrict XIAP, thereby limiting pancreatic cancer development. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2020, 24, 5028–5038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrokhnazar, E.; Moghbelinejad, S.; Najafipour, R.; Teimoori-Toolabi, L. MiR-3664-3p through suppressing ABCG2, CYP3A4, MCL1, and MLH1 increases the sensitivity of colorectal cancer cells to irinotecan. Heliyon 2025, 11, e41933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noonan, E.J.; Place, R.F.; Pookot, D.; Basak, S.; Whitson, J.M.; Hirata, H.; Giardina, C.; Dahiya, R. miR-449a targets HDAC-1 and induces growth arrest in prostate cancer. Oncogene 2009, 28, 1714–1724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Feng, M.; Jiang, X.; Wu, Z.; Li, Z.; Aau, M.; Yu, Q. miR-449a and miR-449b are direct transcriptional targets of E2F1 and negatively regulate pRb-E2F1 activity through a feedback loop by targeting CDK6 and CDC25A. Genes Dev. 2009, 23, 2388–2393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lize, M.; Pilarski, S.; Dobbelstein, M. E2F1-inducible microRNA 449a/b suppresses cell proliferation and promotes apoptosis. Cell Death Differ. 2010, 17, 452–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Lin, Y.W.; Mao, Y.Q.; Wu, J.; Liu, Y.F.; Zheng, X.Y.; Xie, L.P. MicroRNA-449a acts as a tumor suppressor in human bladder cancer through the regulation of pocket proteins. Cancer Lett. 2012, 320, 40–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buurman, R.; Gurlevik, E.; Schaffer, V.; Eilers, M.; Sandbothe, M.; Kreipe, H.; Wilkens, L.; Schlegelberger, B.; Kuhnel, F.; Skawran, B. Histone deacetylases activate hepatocyte growth factor signaling by repressing microRNA-449 in hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Gastroenterology 2012, 143, 811–820.e815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, W.; Huang, B.; Li, Z.; Li, H.; Sun, L.; Zhang, Q.; Qiu, X.; Wang, E. MicroRNA-449a is downregulated in non-small cell lung cancer and inhibits migration and invasion by targeting c-Met. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e64759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, E.B.; Kong, R.; Yin, D.D.; You, L.H.; Sun, M.; Han, L.; Xu, T.P.; Xia, R.; Yang, J.S.; De, W.; et al. Long noncoding RNA ANRIL indicates a poor prognosis of gastric cancer and promotes tumor growth by epigenetically silencing of miR-99a/miR-449a. Oncotarget 2014, 5, 2276–2292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niki, M.; Nakajima, K.; Ishikawa, D.; Nishida, J.; Ishifune, C.; Tsukumo, S.I.; Shimada, M.; Nagahiro, S.; Mitamura, Y.; Yasutomo, K. MicroRNA-449a deficiency promotes colon carcinogenesis. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 10696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meerson, A.; Yehuda, H. Leptin and insulin up-regulate miR-4443 to suppress NCOA1 and TRAF4, and decrease the invasiveness of human colon cancer cells. BMC Cancer 2016, 16, 882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonafe, G.A.; Boschiero, M.N.; Sodre, A.R.; Ziegler, J.V.; Rocha, T.; Ortega, M.M. Natural Plant Compounds: Does Caffeine, Dipotassium Glycyrrhizinate, Curcumin, and Euphol Play Roles as Antitumoral Compounds in Glioblastoma Cell Lines? Front. Neurol. 2021, 12, 784330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, R.; Liu, Z.; Han, L.; Yang, Y.; Wu, F.; Jiang, Q.; Zhang, H.; Ma, R.; Miao, J.; He, K.; et al. miR-22 and miR-214 targeting BCL9L inhibit proliferation, metastasis, and epithelial-mesenchymal transition by down-regulating Wnt signaling in colon cancer. FASEB J. 2019, 33, 5411–5424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, M.; Yang, Y.; Niu, L.; Li, P.; Chen, Y.; Liao, P.; Wang, Y.; Zheng, J.; Chen, F.; He, H.; et al. MiR-125b-5p modulates the function of regulatory T cells in tumor microenvironment by targeting TNFR2. J. Immunother. Cancer 2022, 10, e005241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, S.S.; Zhang, G.J.; Liu, Z.L.; Tian, H.P.; He, Y.; Meng, C.Y.; Li, L.F.; Wang, Z.W.; Zhou, T. MicroRNA-22 suppresses the growth, migration and invasion of colorectal cancer cells through a Sp1 negative feedback loop. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 36266–36278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Xia, S.; Tian, H.; Liu, Z.; Zhou, T. Clinical significance of miR-22 expression in patients with colorectal cancer. Med. Oncol. 2012, 29, 3108–3112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Zhu, Y.; Lv, T.; Luo, M.; Jiang, Y.; Sun, L.; Zheng, S.; Jiang, D.; Ruan, S. Resveratrol restrains colorectal cancer metastasis by regulating miR-125b-5p/TRAF6 signaling axis. Am. J. Cancer Res. 2024, 14, 2390–2407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Jiang, M.; Liao, P.; Yang, Y.; Chen, Z.; Gao, Y.; Wang, Y.; Chou, C.K.; Chen, X. miR-125b-5p sensitizes colorectal cancer to anti-PD-L1 therapy by decreasing TNFR2 expression on tumor cells. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2025, 117, qiaf059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronisz, A.; Godlewski, J.; Wallace, J.A.; Merchant, A.S.; Nowicki, M.O.; Mathsyaraja, H.; Srinivasan, R.; Trimboli, A.J.; Martin, C.K.; Li, F.; et al. Reprogramming of the tumour microenvironment by stromal PTEN-regulated miR-320. Nat. Cell Biol. 2011, 14, 159–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tadano, T.; Kakuta, Y.; Hamada, S.; Shimodaira, Y.; Kuroha, M.; Kawakami, Y.; Kimura, T.; Shiga, H.; Endo, K.; Masamune, A.; et al. MicroRNA-320 family is downregulated in colorectal adenoma and affects tumor proliferation by targeting CDK6. World J. Gastrointest. Oncol. 2016, 8, 532–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, Y.; Li, S.; Tang, L. MicroRNA 320, an Anti-Oncogene Target miRNA for Cancer Therapy. Biomedicines 2021, 9, 591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, J.Y.; Huang, Y.; Li, J.P.; Zhang, X.; Wang, L.; Meng, Y.L.; Yan, B.; Bian, Y.Q.; Zhao, J.; Wang, W.Z.; et al. MicroRNA-320a suppresses human colon cancer cell proliferation by directly targeting beta-catenin. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2012, 420, 787–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; He, X.; Liu, Y.; Ye, Y.; Zhang, H.; He, P.; Zhang, Q.; Dong, L.; Liu, Y.; Dong, J. microRNA-320a inhibits tumor invasion by targeting neuropilin 1 and is associated with liver metastasis in colorectal cancer. Oncol. Rep. 2012, 27, 685–694. [Google Scholar]

- Vishnubalaji, R.; Hamam, R.; Yue, S.; Al-Obeed, O.; Kassem, M.; Liu, F.F.; Aldahmash, A.; Alajez, N.M. MicroRNA-320 suppresses colorectal cancer by targeting SOX4, FOXM1, and FOXQ1. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 35789–35802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yufeng, Z.; Ming, Q.; Dandan, W. MiR-320d Inhibits Progression of EGFR-Positive Colorectal Cancer by Targeting TUSC3. Front. Genet. 2021, 12, 738559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Xu, Q.; Shang, J.; Lu, L.; Chen, G. Crocin inhibits the migration, invasion, and epithelial-mesenchymal transition of gastric cancer cells via miR-320/KLF5/HIF-1alpha signaling. J. Cell. Physiol. 2019, 234, 17876–17885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byun, H.J.; Darvin, P.; Kang, D.Y.; Sp, N.; Joung, Y.H.; Park, J.H.; Kim, S.J.; Yang, Y.M. Silibinin downregulates MMP2 expression via Jak2/STAT3 pathway and inhibits the migration and invasive potential in MDA-MB-231 cells. Oncol. Rep. 2017, 37, 3270–3278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, S.J.; Jung, S.P.; Han, J.; Kim, S.; Kim, J.S.; Nam, S.J.; Lee, J.E.; Kim, J.H. Silibinin inhibits TPA-induced cell migration and MMP-9 expression in thyroid and breast cancer cells. Oncol. Rep. 2013, 29, 1343–1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sameri, S.; Mohammadi, C.; Mehrabani, M.; Najafi, R. Targeting the hallmarks of cancer: The effects of silibinin on proliferation, cell death, angiogenesis, and migration in colorectal cancer. BMC Complement. Med. Ther. 2021, 21, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, K.Y.; Lin, L.C.; Tseng, T.Y.; Wang, S.C.; Tsai, T.H. Oral bioavailability of curcumin in rat and the herbal analysis from Curcuma longa by LC-MS/MS. J. Chromatogr. B 2007, 853, 183–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapetanovic, I.M.; Muzzio, M.; Huang, Z.; Thompson, T.N.; McCormick, D.L. Pharmacokinetics, oral bioavailability, and metabolic profile of resveratrol and its dimethylether analog, pterostilbene, in rats. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 2011, 68, 593–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, L.; Diao, Z.; Xia, J.; Zhang, J.; Xu, Y.; Wu, Y.; Liu, Z.; Jiang, C.; Peng, Y.; Song, Z.; et al. Comprehensive Evaluation of Metabolism and the Contribution of the Hepatic First-Pass Effect in the Bioavailability of Glabridin in Rats. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2023, 71, 1944–1956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Selc, M.; Macova, R.; Babelova, A. Novel Strategies Enhancing Bioavailability and Therapeutical Potential of Silibinin for Treatment of Liver Disorders. Drug Des. Dev. Ther. 2024, 18, 4629–4659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sakai, Y.; Otsuka, K. Discovering Anticancer Effects of Phytochemicals on MicroRNA in the Context of Data Mining. Nutrients 2025, 17, 3913. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17243913

Sakai Y, Otsuka K. Discovering Anticancer Effects of Phytochemicals on MicroRNA in the Context of Data Mining. Nutrients. 2025; 17(24):3913. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17243913

Chicago/Turabian StyleSakai, Yumi, and Kurataka Otsuka. 2025. "Discovering Anticancer Effects of Phytochemicals on MicroRNA in the Context of Data Mining" Nutrients 17, no. 24: 3913. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17243913

APA StyleSakai, Y., & Otsuka, K. (2025). Discovering Anticancer Effects of Phytochemicals on MicroRNA in the Context of Data Mining. Nutrients, 17(24), 3913. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17243913