Structural and Physicochemical Properties of Chlorella pyrenoidosa Neutral/Acidic Polysaccharides and Their Differential Regulatory Effects on Gut Microbiota and Metabolites in In Vitro Fermentation Model

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Extraction and Purification of CPP

2.3. Determination of Polysaccharide Compositions

2.4. Structure Characterization

2.4.1. Ultraviolet (UV) Analysis

2.4.2. Molecular Weight (Mw) Measurements

2.4.3. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectrum (FT-IR) Analysis

2.4.4. Determination of Monosaccharide Composition

2.4.5. Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) Analysis of Polysaccharides

2.4.6. Circular Dichroism (CD) Spectroscopy

2.4.7. Congo Red Experiment

2.5. Physicochemical Properties

2.5.1. Steady-State Rheological Test

2.5.2. Water Solubility of Polysaccharides

2.5.3. Thermal Characteristics

2.6. In Vitro Fermentation of CPP-1 and CPP-2

2.6.1. Fermentation

2.6.2. Gut Microbiota Analysis

2.6.3. Untargeted Metabolomic Analysis

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

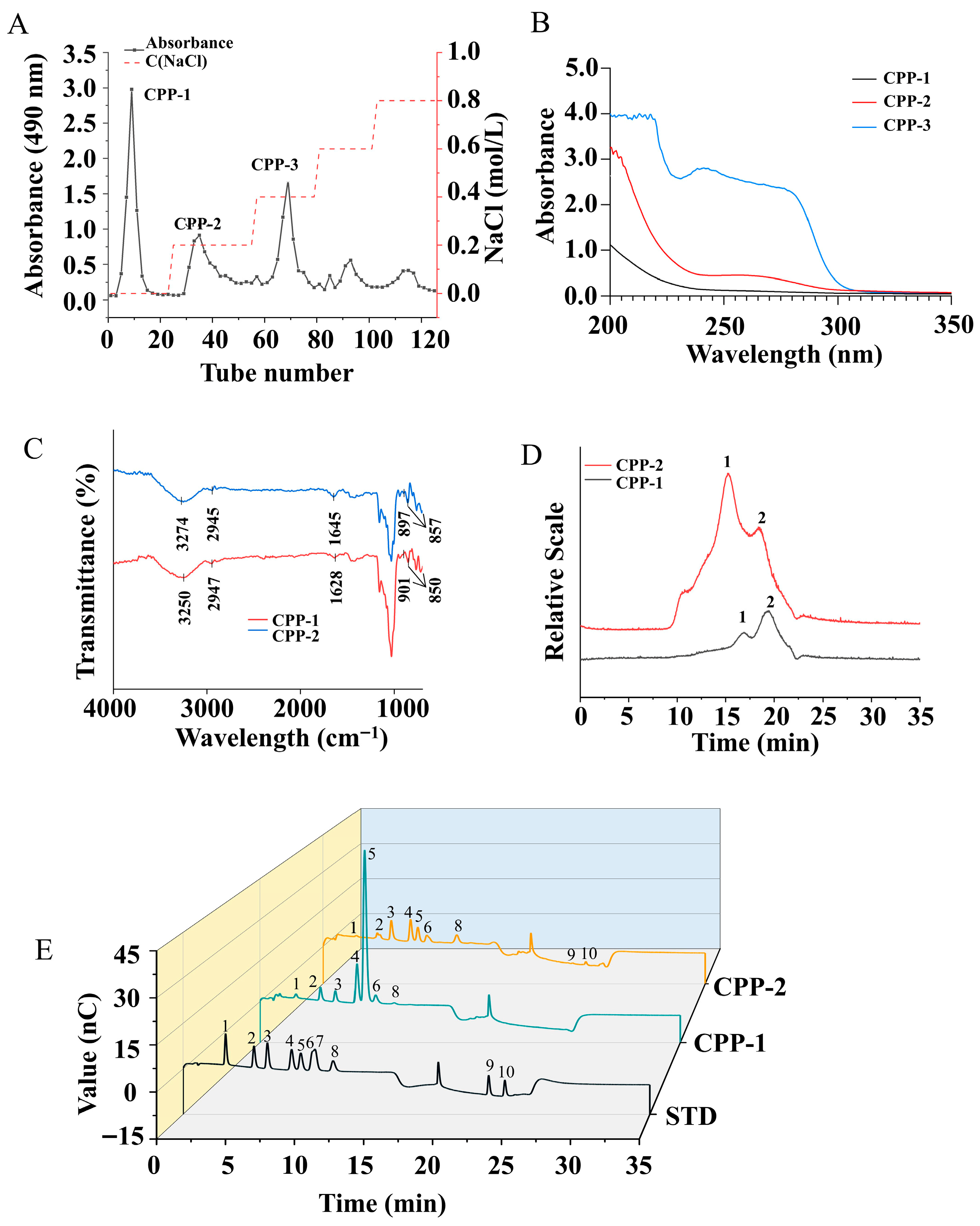

3.1. Purification of CPP and Composition of Purified Polysaccharide Components

3.2. Structural Characterization

3.2.1. FT-IR Analysis

3.2.2. Mw Analysis of Polysaccharides

3.2.3. Monosaccharide Composition Analysis

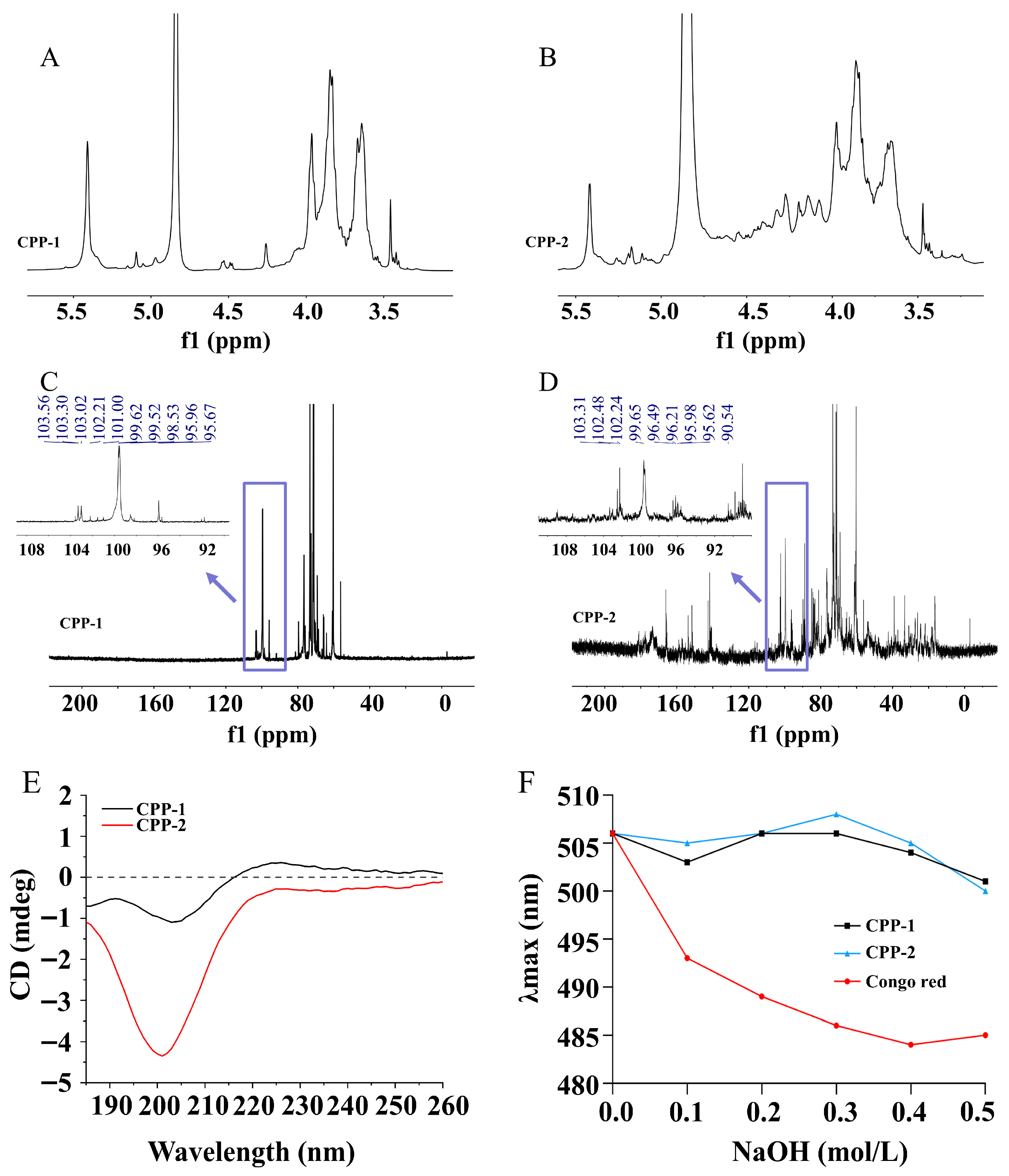

3.2.4. NMR Analysis

3.2.5. Analysis of Asymmetry of Polysaccharides by CD

3.2.6. Analysis of Spatial Conformation of Polysaccharides by Congo Red Experiment

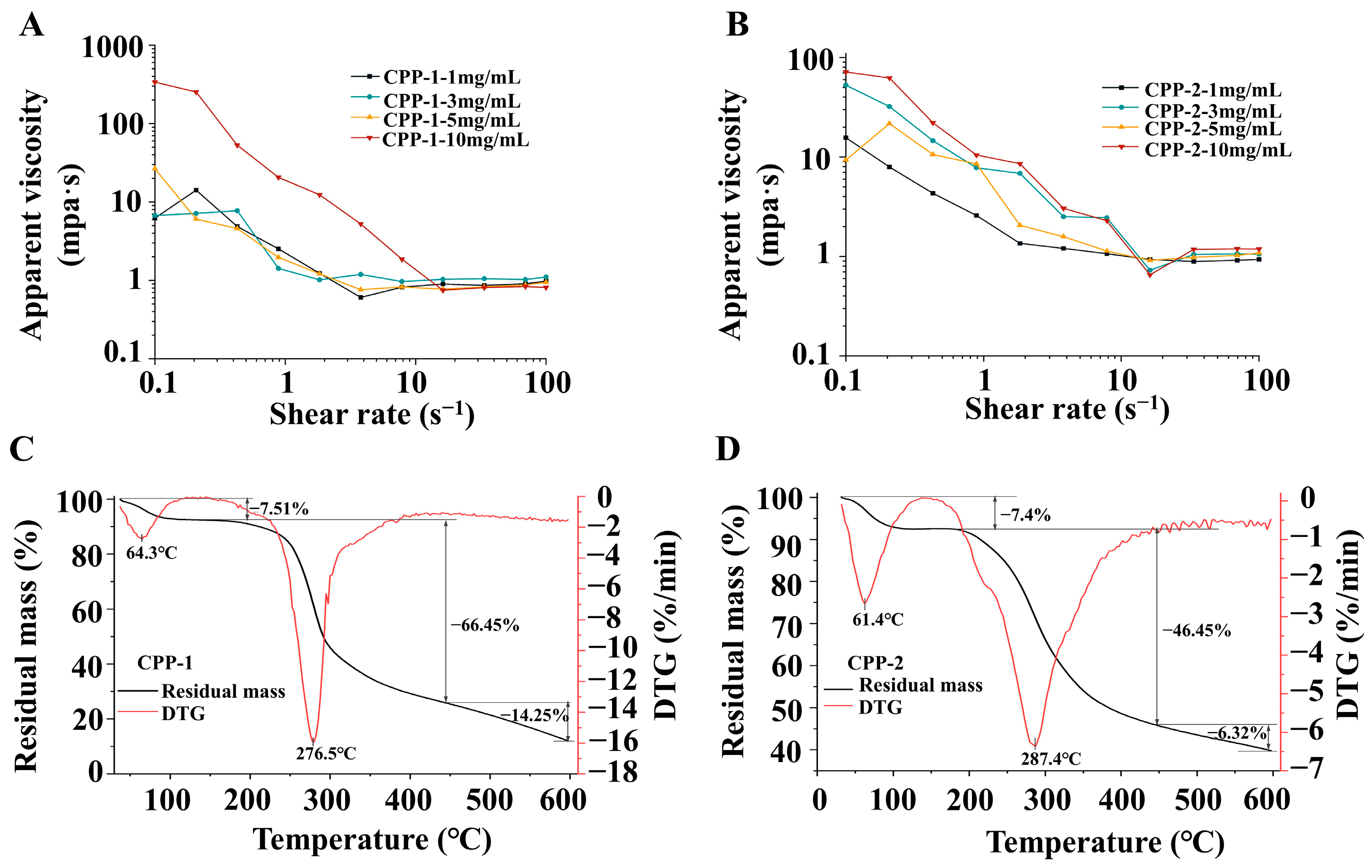

3.3. Analysis of Processing-Related Properties

3.3.1. Analysis of Steady Shear Rheological Properties

3.3.2. Analysis of Water Solubility

3.3.3. Thermal Stability Analysis

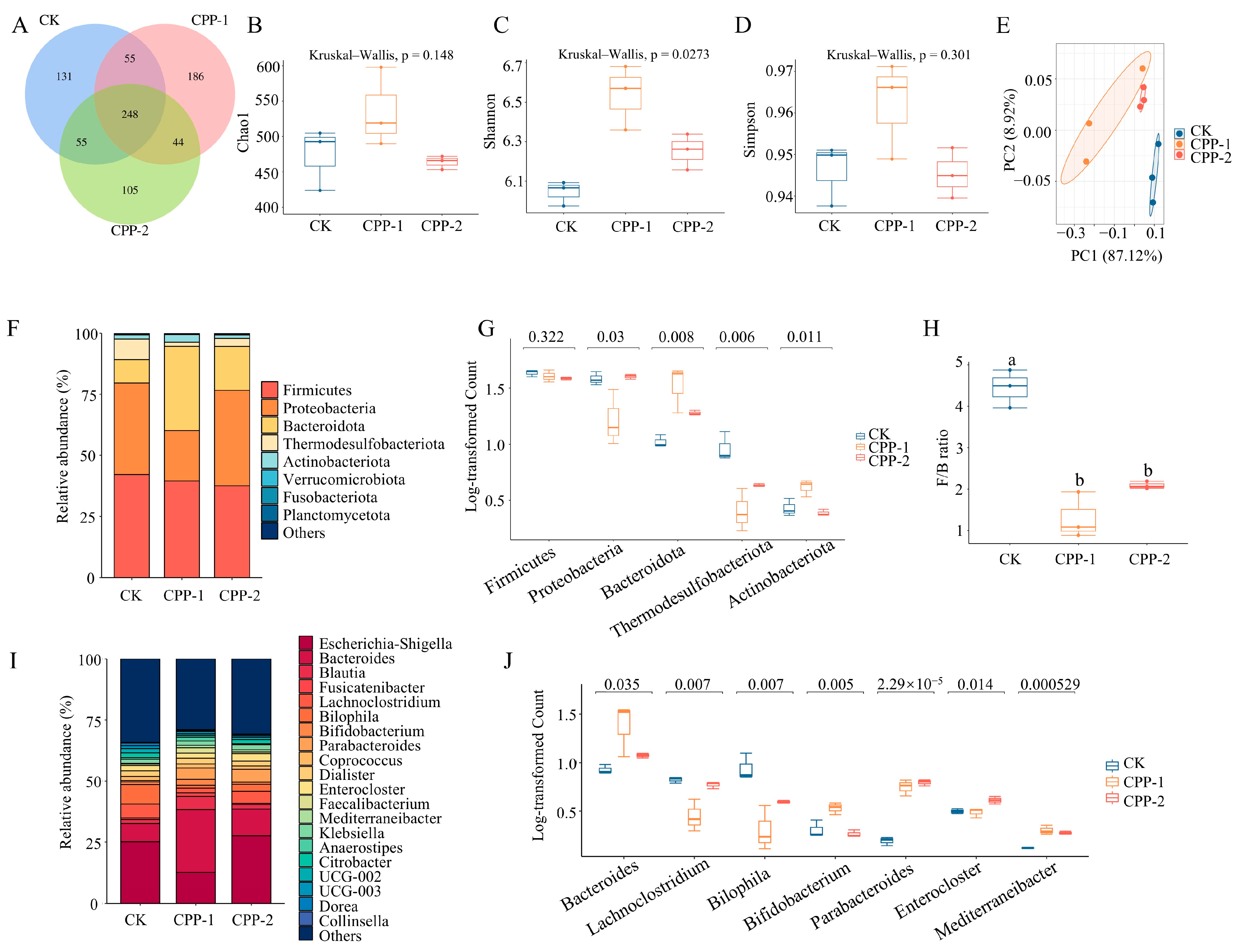

3.4. Effects of CPP-1 and CPP-2 on Gut Microbiota

3.5. Predicted Changes in Metabolic Pathways of Microbiota

3.6. Effects of CPP-1 and CPP-2 on Microbial Metabolites

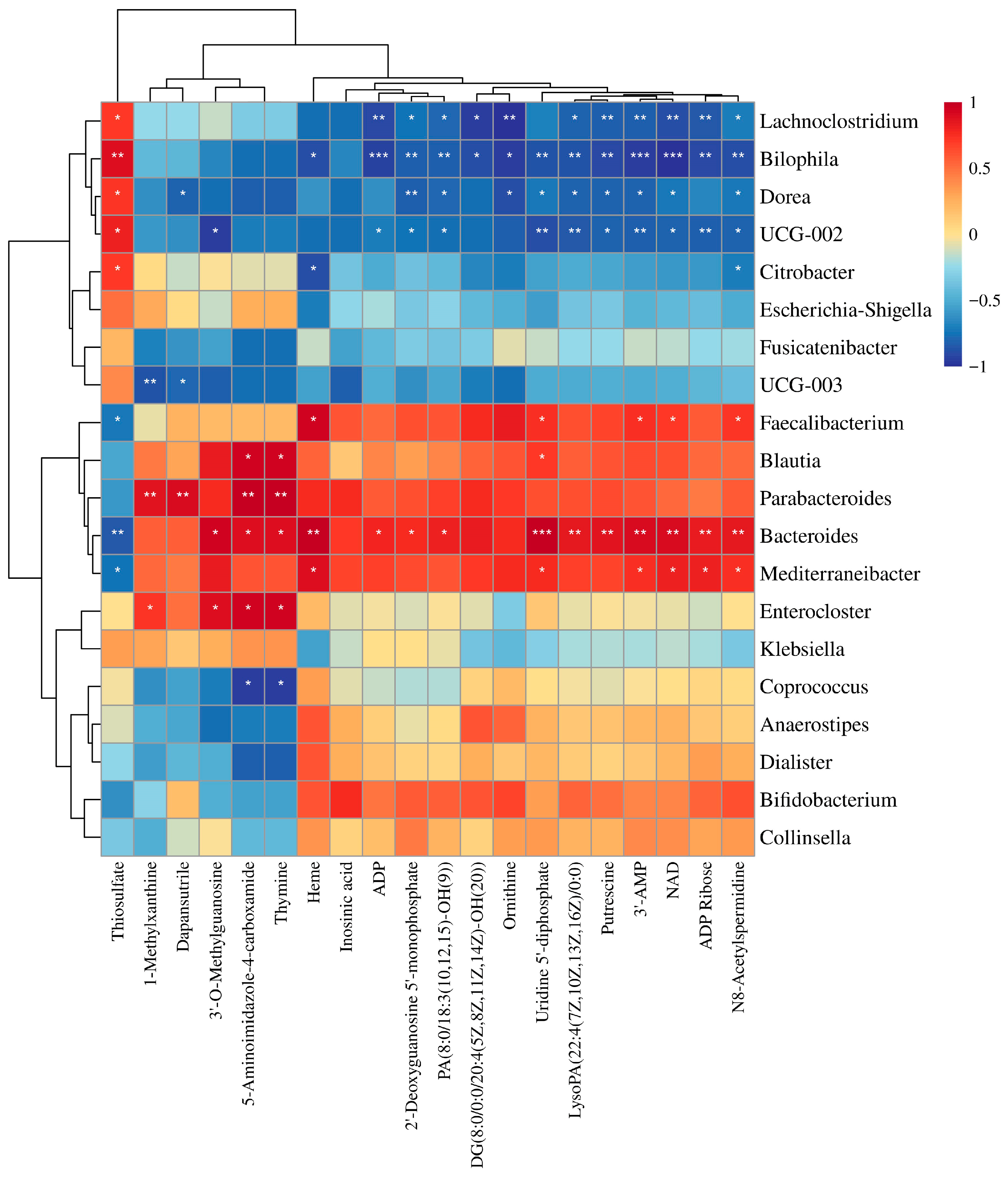

3.7. Correlation Analysis of Gut Microbiota and Metabolites

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Shang, Z.; Ye, H.; Li, Q.; Zha, X.; Luo, J. Potential of non-digestible polysaccharides as GLP-1 secretagogues: Action mechanisms, structure-activity relationships and clinical applications. Carbohydr. Polym. 2025, 367, 124024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, R.; Yang, G.; Lai, H.; Zheng, Q.; Xia, W.; Zhao, M. Structural characterization and human gut microbiota fermentation in vitro of a polysaccharide from Fucus vesiculosus. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 275, 133369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.; Yuan, Q.; Feng, K.; Zhang, J.; Gan, R.; Zou, L.; Wang, S. Fecal fermentation characteristics of Rheum tanguticum polysaccharide and its effect on the modulation of gut microbial composition. Chin. Med. 2022, 17, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Y.; Yao, J.; Gao, R.; Hao, J.; Liu, Y.; Liu, S. Interactions of non-starch polysaccharides with the gut microbiota and the effect of non-starch polysaccharides with different structures on the metabolism of the gut microbiota: A review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 296, 139664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Chang, S.; Zhang, X.; Luo, F.; Li, W.; Ren, J. The fate of dietary polysaccharides in the digestive tract. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2024, 150, 104606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, M.; Yu, J.; Shi, X.; Zhu, J.; Gao, X.; Liu, W. Polysaccharides catabolism by the human gut bacterium—Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron: Advances and perspectives. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2021, 61, 3569–3588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.; Yuan, Q.; Guo, H.; Fu, Y.; Li, F.; Wang, S.; Gan, R. Dynamic changes of structural characteristics of snow chrysanthemum polysaccharides during in vitro digestion and fecal fermentation and related impacts on gut microbiota. Food Res. Int. 2021, 141, 109888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, G.; Xie, Y.; Gao, X.; Xiao, C.; Yong, T.; Huang, L.; Cai, M.; Liu, Y.; Hu, H.; Chen, S. Selective impact of three homogenous polysaccharides with different structural characteristics from Grifola frondosa on human gut microbial composition and the structure-activity relationship. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 269, 132143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, K.; Fu, C.; Du, H.; Chen, S.; Liu, D.; Ma, G.; Xiao, H. Structure characterization, simulated digestion, and microbial modulation of Pleurotus ostreatus polysaccharides. Food Chem. 2025, 493, 145849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maghzian, A.; Aslani, A.; Zahedi, R.; Yaghoubi, M. How to effectively produce value-added products from microalgae? Renew. Energy 2023, 204, 262–276. [Google Scholar]

- Ibrahim, T.N.B.T.; Feisal, N.A.S.; Kamaludin, N.H.; Cheah, W.Y.; How, V.; Bhatnagar, A.; Ma, Z.; Show, P.L. Biological active metabolites from microalgae for healthcare and pharmaceutical industries: A comprehensive review. Bioresour. Technol. 2023, 372, 128661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Ma, Y.; Zhang, L.; Han, J.; Lei, Y.; Le, Y.; Huang, C.; Kan, J.; Fu, C. Extraction, functionality, and applications of Chlorella pyrenoidosa protein/peptide. Curr. Res. Food Sci. 2023, 7, 100621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, Q.; Li, H.; Wei, Z.; Lv, K.; Gao, C.; Liu, Y.; Zhao, L. Isolation, structures and biological activities of polysaccharides from Chlorella: A review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 163, 2199–2209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.; Zheng, F.; Chen, M.; Liu, C.; Zheng, L. Chlorella pyrenoidosa polysaccharides supplementation increases Drosophila melanogaster longevity at high temperature. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 276, 133844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wan, X.Z.; Li, X.Q.; Liu, D.; Gao, X.; Chen, Y.; Chen, Z.; Fu, C.; Lin, L.; Liu, B.; Zhao, C. Physicochemical characterization and antioxidant effects of green microalga Chlorella pyrenoidosa polysaccharide by regulation of microRNAs and gut microbiota in Caenorhabditis elegans. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 168, 152–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, W.; Zhu, S.; Li, S.; Feng, Y.; Wu, H.; Zeng, M. Microalgae polysaccharides ameliorates obesity in association with modulation of lipid metabolism and gut microbiota in high-fat-diet fed C57BL/6 mice. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 182, 1371–1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, K.; Yuan, Q.; Li, H.; Li, T.; Ma, H.; Gao, C.; Zhang, S.; Liu, Y.; Zhao, L. Chlorella pyrenoidosa Polysaccharides as a Prebiotic to Modulate Gut Microbiota: Physicochemical Properties and Fermentation Characteristics In Vitro. Foods 2022, 11, 725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, P.; Liu, H.; Ding, M.; Zhang, K.; Shang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Ma, Y. Physicochemical characterization, digestion profile and gut microbiota regulation activity of intracellular polysaccharides from Chlorella zofingiensis. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 253, 126881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Han, L.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, L.; Jing, J.; Gao, A. Genus unclassified_Muribaculaceae and microbiota-derived butyrate and indole-3-propionic acid are involved in benzene-induced hematopoietic injury in mice. Chemosphere 2023, 313, 137499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DuBois, M.; Gilles, K.A.; Hamilton, J.K.; Rebers, P.A.; Smith, F. Colorimetric Method for Determination of Sugars and Related Substances. Anal. Chem. 1956, 28, 350–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filisetti-Cozzi, T.M.C.C.; Carpita, N.C. Measurement of uronic acids without interference from neutral sugars. Anal. Biochem. 1991, 197, 157–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradford, M.M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 1976, 72, 248–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, C.; Zhu, P.; Ma, S.; Wang, M.; Hu, Y. Purification, characterization and immunomodulatory activity of polysaccharides from stem lettuce. Carbohydr. Polym. 2018, 188, 236–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia, M.; Li, D.; Wang, R.; Wang, A.; Strappe, P.; Wu, Q.; Shang, W.; Wang, X.; Zhuang, M.; Blanchard, C.; et al. Gut microbiota derived structural changes of phenolic compounds from colored rice and its corresponding fermentation property. Food Funct. 2022, 13, 10759–10768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Du, P.; Cheng, Y.; Guo, Y.; Hu, B.; Yao, W.; Zhu, X.; Qian, H. Study on fecal fermentation characteristics of aloe polysaccharides in vitro and their predictive modeling. Carbohydr. Polym. 2021, 256, 117571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, B.; Zhao, X.; Luo, L.; Wan, P.; Chen, H.; Pan, J. Structural characterization, and in vitro immunostimulatory and antitumor activity of an acid polysaccharide from Spirulina platensis. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 196, 46–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, S.; Wang, B.; Lv, W.; Li, B.; Xiao, H.; Lin, R. Physicochemical properties, structure and biological activity of ginger polysaccharide: Effect of microwave infrared dual-field coupled drying. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 281, 136474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, L.; Wu, L.; Li, L.; Zhu, J.; Chen, X.; Zhang, S.; Li, L.; Yan, J. Physicochemical, structural, and rheological characteristics of pectic polysaccharides from fresh passion fruit (Passiflora edulis f. flavicarpa L.) peel. Food Hydrocoll. 2023, 136, 108301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, R.; Cui, M.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, M.; Li, F.; Liu, K. Isolation, structure identification and anti-inflammatory activity of a polysaccharide from Phragmites rhizoma. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 161, 810–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Q.; Xue, Z.; Luo, Y.; Lin, Y.; Lai, M.; Xu, H.; Liu, B.; Zheng, M.; Lv, F.; Zeng, F. Low molecular weight polysaccharide of Tremella fuciformis exhibits stronger antioxidant and immunomodulatory activities than high molecular weight polysaccharide. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 281, 136097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, F.; Hong, R.; Zhang, R.; Yi, Y.; Dong, L.; Liu, L.; Jia, X.; Ma, Y.; Zhang, M. Physicochemical and biological properties of longan pulp polysaccharides modified by Lactobacillus fermentum fermentation. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 125, 232–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Liu, X.; Wu, L.; Tong, A.; Zhao, L.; Liu, B.; Zhao, C. Physicochemical characterization of polysaccharides from Chlorella pyrenoidosa and its anti-ageing effects in Drosophila melanogaster. Carbohydr. Polym. 2018, 185, 120–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, J.; Kim, S.M. Characterization and immunomodulatory activities of polysaccharides extracted from green alga Chlorella ellipsoidea. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2017, 95, 106–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, H.; Wang, J.; Yin, J.; Nie, S.; Xie, M. A review of NMR analysis in polysaccharide structure and conformation: Progress, challenge and perspective. Food Res. Int. 2021, 143, 110290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Z.; Wang, H.; Feng, T.; Yao, L.; Sun, M.; Song, S.; Liu, Q.; Yu, C. Physicochemical properties, techno-functional attributes, and molecular correlations of fractionated Ulva prolifera polysaccharides. LWT 2025, 217, 117396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zhu, Z.; Tang, Y.; Wang, M.; Wang, Z.; Liu, A.; Zhang, Y. Structural properties of polysaccharides from cultivated fruit bodies and mycelium of Cordyceps militaris. Carbohydr. Polym. 2016, 142, 63–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, L.; Deji; Zhu, M.; Chen, D.; Lu, Y. Juniperus pingii var. wilsonii acidic polysaccharide: Extraction, characterization and anticomplement activity. Carbohydr. Polym. 2020, 231, 115728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.; Wang, Y.; Yang, J.; Gu, D.; Kang, S.; Liu, Y.; Jin, H.; Wei, F.; Ma, S. Anti-aging activities of neutral and acidic polysaccharides from Polygonum multiflorum Thunb in Caenorhabditis elegans. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 257, 128724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Y.; Hou, S.; Song, S.; Zhang, B.; Ai, C.; Chen, X.; Liu, N. Impact of acidic, water and alkaline extraction on structural features, antioxidant activities of Laminaria japonica polysaccharides. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 112, 985–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, Z.; Huang, G.; Huang, H. Ultrasonic-assisted extraction, analysis and properties of purple mangosteen scarfskin polysaccharide and its acetylated derivative. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2024, 109, 107010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, X.; Guan, C.; Wang, H.; Liu, Q.; Zhang, L.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, X. Chlamydomonas reinhardtii polysaccharides retard rice starch retrogradation by weakening hydrogen bond strength within starch double helices. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 296, 139570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Song, L.; Chen, P.; Liu, H.; Zhang, X. Extraction, Rheological, and Physicochemical Properties of Water-Soluble Polysaccharides with Antioxidant Capacity from Penthorum chinense Pursh. Foods 2023, 12, 2335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Xue, Y. Optimization of microwave assisted extraction, chemical characterization and antitumor activities of polysaccharides from porphyra haitanensis. Carbohydr. Polym. 2019, 206, 179–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Yu, H.; Liu, Y.; Qin, Z.; Liu, H.; Ma, Y.; Wang, X. Isolation and structural characterization of cell wall polysaccharides from sesame kernel. LWT 2022, 163, 113574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Naggar, N.E.-A.; Hussein, M.H.; Shaaban-Dessuuki, S.A.; Dalal, S.R. Production, extraction and characterization of Chlorella vulgaris soluble polysaccharides and their applications in AgNPs biosynthesis and biostimulation of plant growth. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 3011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, Z.; Liu, H.; Yang, J.; Zheng, L.; Huang, J.; Wang, Z.; Xie, C.; Zuo, W.; Xia, X.; Sun, L.; et al. Selective utilization of medicinal polysaccharides by human gut Bacteroides and Parabacteroides species. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, B.; Feng, T.; Song, S.; Wang, H.; Yao, L.; Zhuang, H.; Zhang, X.; Liu, Q.; Yu, C.; Sun, M. Effects of complex polysaccharides by Ficus carica Linn. polysaccharide and peach gum on the development and metabolites of human gut microbiota. Food Hydrocoll. 2024, 154, 110061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Huang, Z.; Jia, R.; Lv, X.; Zhao, C.; Liu, B. Spirulina platensis polysaccharides attenuate lipid and carbohydrate metabolism disorder in high-sucrose and high-fat diet-fed rats in association with intestinal microbiota. Food Res. Int. 2021, 147, 110530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, N.; Dai, S.; Fan, X.; Li, B.; Chen, M.; Gong, P.; Chen, X. In vitro fermentation of Auricularia auricula polysaccharides and their regulation of human gut microbiota and metabolism. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 306, 141714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, W.; Zou, Z.; Ye, B.; Zhou, Y. Gut microbiota and associated metabolites: Key players in high-fat diet-induced chronic diseases. Gut Microbes 2025, 17, 2494703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Aweya, J.J.; Huang, Z.; Kang, Z.; Bai, Z.; Li, K.; He, X.; Liu, Y.; Chen, X.; Cheong, K.-L. In vitro fermentation of Gracilaria lemaneiformis sulfated polysaccharides and its agaro-oligosaccharides by human fecal inocula and its impact on microbiota. Carbohydr. Polym. 2020, 234, 115894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Yu, C.; Xu, X.; Lei, P.; Xu, H.; Li, S. In vitro digestion and fecal fermentation of Tremella fuciformis exopolysaccharides from basidiospore-derived submerged fermentation. Food Res. Int. 2024, 196, 115019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.X.; Gu, F.T.; Zhu, Y.Y.; Zhao, Z.C.; Li, J.H.; Wu, J.Y. Bifidogenic properties of polysaccharides isolated from mushroom Lentinula edodes and enhanced immunostimulatory activities through Bifidobacterial fermentation. Food Biosci. 2024, 62, 105121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.; Hu, J.; Geng, F.; Nie, S. Bacteroides utilization for dietary polysaccharides and their beneficial effects on gut health. Food Sci. Hum. Wellness 2022, 11, 1101–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Zhao, Z.; Liu, H.; Xia, X.; Ai, C.; Song, S.; Yan, C. Haematococcus pluvialis polysaccharides improve microbiota-driven gut epithelial and vascular barrier and prevent alcoholic steatohepatitis development. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 274, 133014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Qiu, H.; Zhao, J.; Shao, N.; Chen, C.; He, Z.; Zhao, X.; Zhao, J.; Zhou, Y.; Xu, L. Parabacteroides as a promising target for disease intervention: Current stage and pending issues. npj Biofilms Microbiomes 2025, 11, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Peng, B.; Chi-Keung Cheung, P.; Wang, J.; Zheng, X.; You, L. Depolymerized non-digestible sulfated algal polysaccharides produced by hydrothermal treatment with enhanced bacterial fermentation characteristics. Food Hydrocoll. 2022, 130, 107687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Z.; Huang, H.; Wang, L.; Lin, Y.; Wang, B.; Zheng, B.; Zhang, Y.; Pan, L. Steam-exploded Dictyophora indusiata polysaccharide regulated gut microbiota based on dynamic in vitro stomach-intestine digestion system. Food Biosci. 2024, 62, 105470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, C.; Li, H.; Li, J.; Zou, G.; Li, C.; Fang, Z.; Hu, B.; Wu, W.; Li, X.; Zeng, Z.; et al. In vitro simulated digestion and fermentation behaviors of polysaccharides from Pleurotus cornucopiae and their impact on the gut microbiota. Food Funct. 2024, 15, 10051–10066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Li, M.; Chen, Q.; Li, X.; Chen, L.; Dong, Z.; Zhu, W.; Yang, Y.; Liu, Z.; Chen, Q. Programmable probiotics modulate inflammation and gut microbiota for inflammatory bowel disease treatment after effective oral delivery. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 3432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Z.; Zhu, L.; Gao, M.; Yu, D.; Zhang, Z.; Zhu, L.; Zhan, X. Effects of In Vitro Fermentation of Polysialic Acid and Sialic Acid on Gut Microbial Community Composition and Metabolites in Healthy Humans. Foods 2024, 13, 481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Fan, J.; Li, T.; Yan, X.; Jiang, Y. Nuciferine Protects Against High-Fat Diet-Induced Hepatic Steatosis via Modulation of Gut Microbiota and Bile Acid Metabolism in Rats. J. Agric. Food. Chem. 2022, 70, 12014–12028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, R.; Fei, F.; Jin, D.; Yang, H.; Xu, Z.; Cao, B.; Li, J. The integrated analysis of gut microbiota and metabolome revealed steroid hormone biosynthesis is a critical pathway in liver regeneration after 2/3 partial hepatectomy. Front. Pharmacol. 2024, 15, 1407401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gholami, H.; Chmiel, J.A.; Burton, J.P.; Maleki Vareki, S. The Role of Microbiota-Derived Vitamins in Immune Homeostasis and Enhancing Cancer Immunotherapy. Cancers 2023, 15, 1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, H.; Fu, Y.; Liu, F.; Zhang, W.; Yuan, Y.; Yang, G.; Yang, M.; Li, L. AuCePt porous hollow cascade nanozymes targeted delivery of disulfiram for alleviating hepatic insulin resistance. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2024, 22, 660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.; Chen, B.; Zhang, J. Intracellular Insulin and Impaired Autophagy in a Zebrafish model and a Cell Model of Type 2 diabetes. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2017, 13, 985–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Yang, H.; Yang, T.; Zhang, Z.; Guan, L.; Gao, L.; Ma, H.; Zhang, H.; Song, N.; Tong, Z.; et al. Dysregulated proteasome activity and steroid hormone biosynthesis are associated with mortality among patients with acute COVID-19. J. Transl. Med. 2024, 22, 626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.; Zhang, L.; Li, Y.; Su, W.; Abd El-Aty, A.M.; Tan, M. Design and preparation of NMN nanoparticles based on protein-marine polysaccharide with increased NAD+ level in D-galactose induced aging mice model. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2024, 239, 113903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waddell, J.; Khatoon, R.; Kristian, T. Cellular and Mitochondrial NAD Homeostasis in Health and Disease. Cells 2023, 12, 1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katsyuba, E.; Mottis, A.; Zietak, M.; De Franco, F.; van der Velpen, V.; Gariani, K.; Ryu, D.; Cialabrini, L.; Matilainen, O.; Liscio, P.; et al. De novo NAD+ synthesis enhances mitochondrial function and improves health. Nature 2018, 563, 354–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Strassburger, K.; Teleman, A.A. Remote control of AMPK via extracellular adenosine controls tissue growth. Nat. Cell Biol. 2025, 27, 1827–1837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jackson, E.K.; Ren, J.; Gillespie, D.G. 2′,3′-cAMP, 3′-AMP, and 2′-AMP inhibit human aortic and coronary vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation via A2B receptors. Am. J. Physiol.-Heart Circ. Physiol. 2011, 301, H391–H401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Zhu, M. AMP-activated protein kinase: A therapeutic target in intestinal diseases. Open Biol. 2017, 7, 170104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zu, Y.; Wu, C.; Li, F.; Yao, H.; Xia, Y.; Zhang, R.; Li, L.; Chen, S.; Shi, Q.; Xi, S.; et al. The NAMPT enzyme employs a switch that directly senses AMP/ATP and regulates cellular responses to energy stress. Mol. Cell 2025, 85, 2271–2286.e2276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Višnjić, D.; Lalić, H.; Dembitz, V.; Tomić, B.; Smoljo, T. AICAr, a Widely Used AMPK Activator with Important AMPK-Independent Effects: A Systematic Review. Cells 2021, 10, 1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andriyas, T.; Sriswasdi, S.; Tansawat, R.; Uaariyapanichkul, J.; Chomtho, S.; Visuthranukul, C. Inulin supplementation modulates gut microbiota derived metabolites related to brain function in children with obesity. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 34843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Ren, H.; Liu, M.; Li, X.; Sun, D.; Li, N.; Ming, L. Modulation of Intestinal Epithelial Cell Proliferation, Migration, and Differentiation In Vitro by Astragalus Polysaccharides. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e106674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, T.; Liu, T.; Xie, P.; Jiang, S.; Yi, W.; Dai, P.; Guo, X. UPLC-MS-based urine nontargeted metabolic profiling identifies dysregulation of pantothenate and CoA biosynthesis pathway in diabetic kidney disease. Life Sci. 2020, 258, 118160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Q.; Han, X.; Zheng, M.; Lv, F.; Liu, B.; Zeng, F. Preparation of low molecular weight polysaccharides from Tremella fuciformis by ultrasonic-assisted H2O2-Vc method: Structural characteristics, in vivo antioxidant activity and stress resistance. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2023, 99, 106555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gruenbaum, B.F.; Merchant, K.S.; Zlotnik, A.; Boyko, M. Gut Microbiome Modulation of Glutamate Dynamics: Implications for Brain Health and Neurotoxicity. Nutrients 2024, 16, 4405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- James, A.; Ke, H.; Yao, T.; Wang, Y. The Role of Probiotics in Purine Metabolism, Hyperuricemia and Gout: Mechanisms and Interventions. Food Rev. Int. 2023, 39, 261–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wimmer, B.C.; Dwan, C.; De Medts, J.; Duysburgh, C.; Rotsaert, C.; Marzorati, M. Undaria pinnatifida Fucoidan Enhances Gut Microbiome, Butyrate Production, and Exerts Anti-Inflammatory Effects in an In Vitro Short-Term SHIME® Coupled to a Caco-2/THP-1 Co-Culture Model. Mar. Drugs 2025, 23, 242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Sample | CPP-1 | CPP-2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total sugar (%) | 86.89 ± 2.71 a | 50.49 ± 1.92 b | ||

| Uronic acid (%) | ND | 9.00 ± 0.11 | ||

| Protein (%) | ND | 0.56 ± 0.03 | ||

| Water solubility (%) | 99.17 ± 0.03 a | 99.12 ± 0.12 a | ||

| Molecular weight | peak 1 | peak 2 | peak 1 | peak 2 |

| Mass fraction (%) | 5.2 | 94.8 | 17.2 | 82.8 |

| Mw (g/mol) | 1.911 × 105 | 1.828 × 104 | 8.100 × 105 | 1.039 × 105 |

| Monosaccharide composition (molar ratio) | ||||

| Fucose | 0.56 | 0.20 | ||

| Rhamnose | 2.18 | 0.82 | ||

| Arabinose | 1.57 | 3.77 | ||

| Galactose | 5.73 | 3.58 | ||

| Glucose | 29.28 | 2.85 | ||

| Xylose | 2.93 | 1.09 | ||

| Fructose | 0.35 | 3.20 | ||

| Galacturonic acid | ND | 0.11 | ||

| Glucuronic acid | ND | 0.66 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cui, Z.; Ma, R.; Pan, X.; Liu, C.; Zhan, J.; Yang, T.; Shen, W.; Tian, Y. Structural and Physicochemical Properties of Chlorella pyrenoidosa Neutral/Acidic Polysaccharides and Their Differential Regulatory Effects on Gut Microbiota and Metabolites in In Vitro Fermentation Model. Nutrients 2025, 17, 3912. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17243912

Cui Z, Ma R, Pan X, Liu C, Zhan J, Yang T, Shen W, Tian Y. Structural and Physicochemical Properties of Chlorella pyrenoidosa Neutral/Acidic Polysaccharides and Their Differential Regulatory Effects on Gut Microbiota and Metabolites in In Vitro Fermentation Model. Nutrients. 2025; 17(24):3912. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17243912

Chicago/Turabian StyleCui, Ziwei, Rongrong Ma, Xiaohua Pan, Chang Liu, Jinling Zhan, Tianyi Yang, Wangyang Shen, and Yaoqi Tian. 2025. "Structural and Physicochemical Properties of Chlorella pyrenoidosa Neutral/Acidic Polysaccharides and Their Differential Regulatory Effects on Gut Microbiota and Metabolites in In Vitro Fermentation Model" Nutrients 17, no. 24: 3912. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17243912

APA StyleCui, Z., Ma, R., Pan, X., Liu, C., Zhan, J., Yang, T., Shen, W., & Tian, Y. (2025). Structural and Physicochemical Properties of Chlorella pyrenoidosa Neutral/Acidic Polysaccharides and Their Differential Regulatory Effects on Gut Microbiota and Metabolites in In Vitro Fermentation Model. Nutrients, 17(24), 3912. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17243912