New Insights into Synergistic Boosts in SCFA Production Across Health Conditions Induced by a Fiber Mixture

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

- (1)

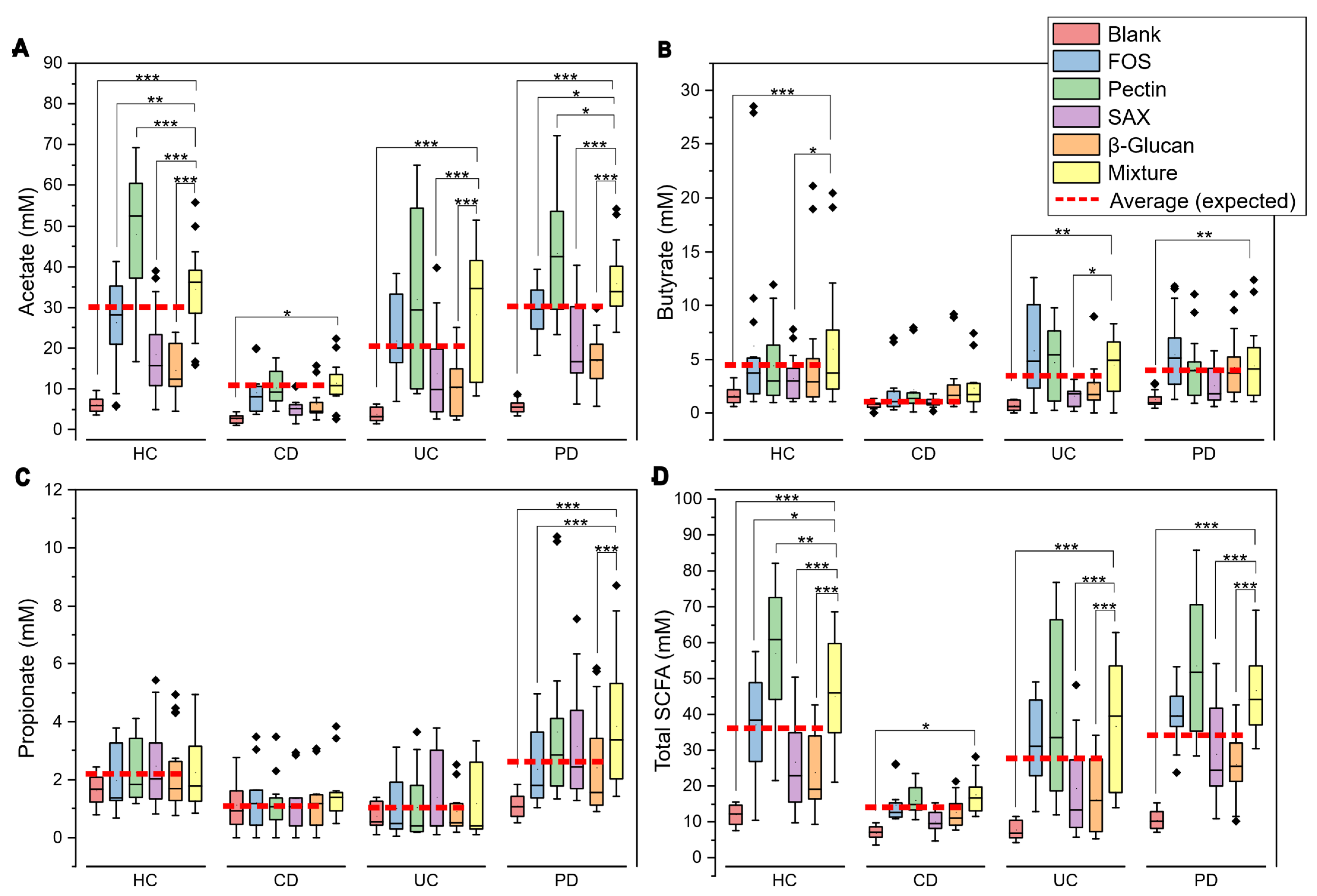

- Comparison of fiber treatments: Within each health condition (HC, PD, CD, UC), observed SCFA values from the fiber mixture were compared with each individual fiber using Tukey’s method for multiple pairwise contrasts. For visualization purposes, the mean SCFA value of the four individual fibers was calculated for each donor.

- (2)

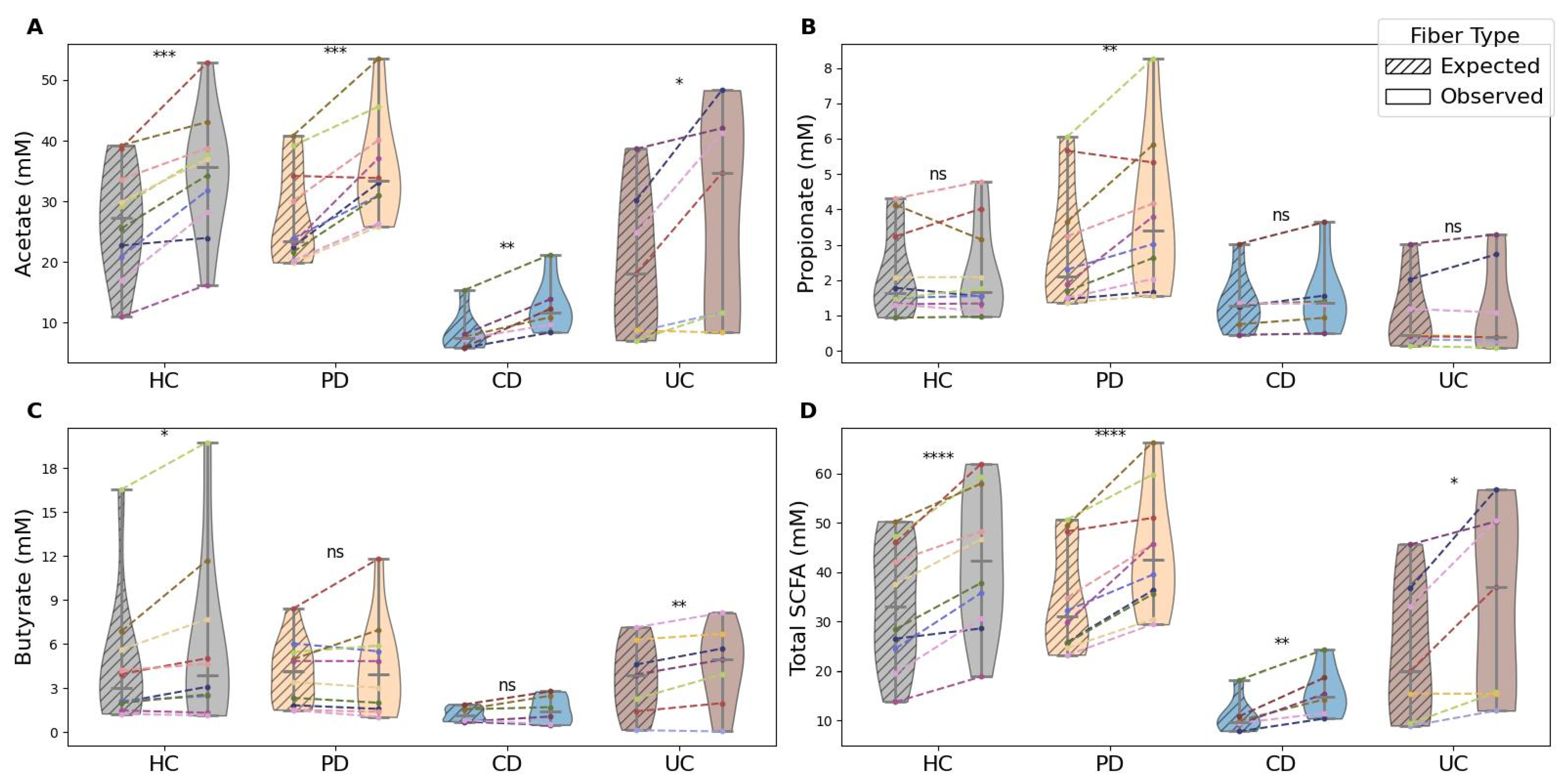

- Observed versus expected mixture performance: A donor-specific expected SCFA value was calculated as the mean of the four individual fibers. Observed and expected mixture values were compared using paired tests within each condition and each SCFA type, with Benjamini–Hochberg correction applied to control false discovery.

- (3)

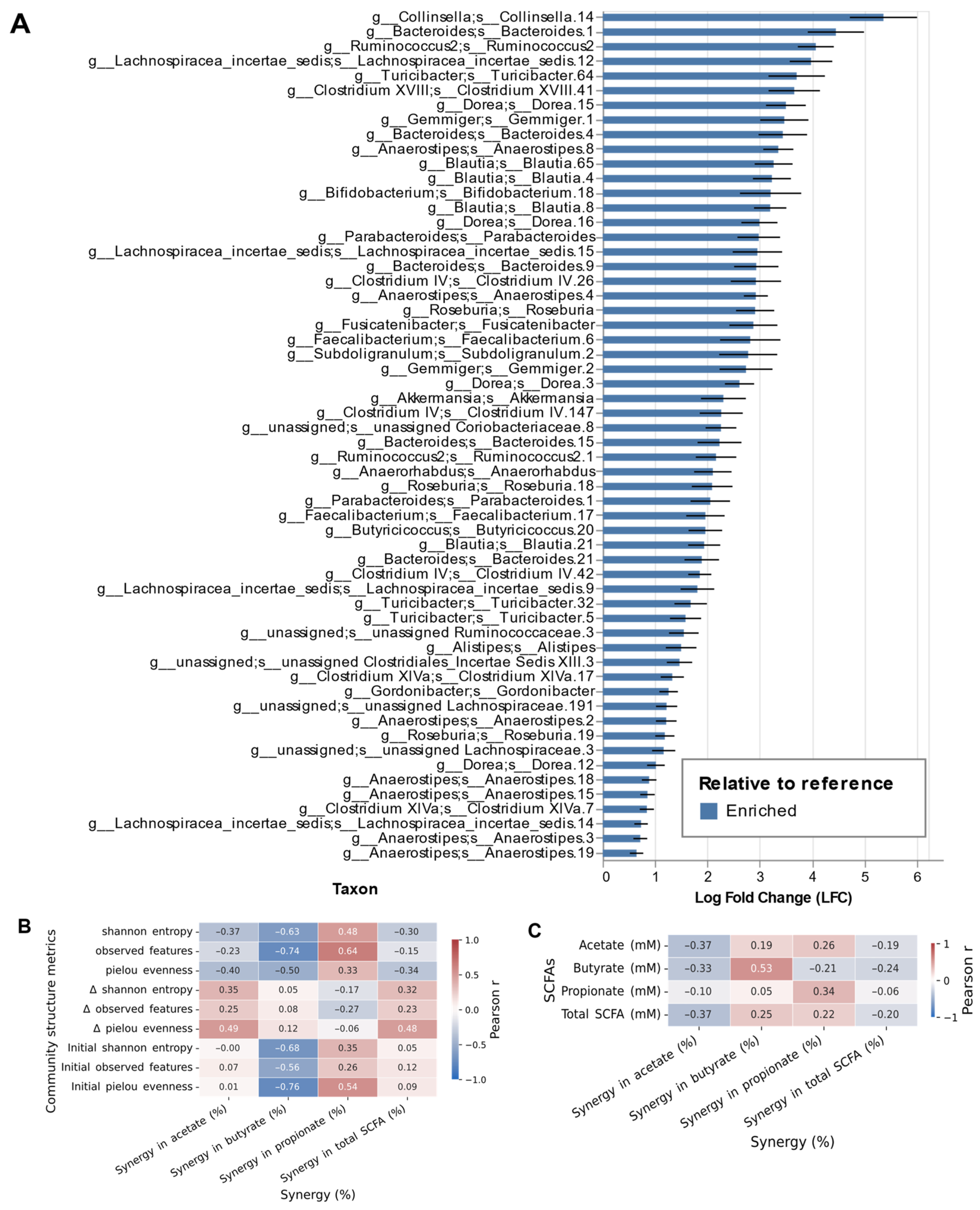

- Synergy quantification: Synergy was defined as the percentage deviation of the observed mixture value from each donor’s expected value, as described before. After applying threshold-based filtering, synergy values for acetate, propionate, butyrate, and total SCFAs were compared across health conditions. Because filtering produced unequal sample sizes, p-values were adjusted using the Holm–Šidák method.

3. Results

3.1. Comparison of Fiber Mixture to Individual Fibers

3.2. Synergy Quantification

3.3. Microbial Correlates of Synergistic SCFA Production

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SCFAs | Short-chain fatty acids |

| HC | Healthy controls |

| CD | Chron’s disease |

| UC | Ulcerative colitis |

| PD | Parkinson’s disease |

References

- Gibson, G.R.; Hutkins, R.; Sanders, M.E.; Prescott, S.L.; Reimer, R.A.; Salminen, S.J.; Scott, K.; Stanton, C.; Swanson, K.S.; Cani, P.D.; et al. Expert Consensus Document: The International Scientific Association for Probiotics and Prebiotics (ISAPP) Consensus Statement on the Definition and Scope of Prebiotics. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2017, 14, 491–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mayer, E.A.; Knight, R.; Mazmanian, S.K.; Cryan, J.F.; Tillisch, K. Gut Microbes and the Brain: Paradigm Shift in Neuroscience. J. Neurosci. 2014, 34, 15490–15496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slavin, J. Fiber and Prebiotics: Mechanisms and Health Benefits. Nutrients 2013, 5, 1417–1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, W.; Sun, S.; Yan, Y.; Zhou, H.; Liu, Z.; Fu, Q. The Role of Short-Chain Fatty Acid in Metabolic Syndrome and Its Complications: Focusing on Immunity and Inflammation. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1519925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Facchin, S.; Bertin, L.; Bonazzi, E.; Lorenzon, G.; De Barba, C.; Barberio, B.; Zingone, F.; Maniero, D.; Scarpa, M.; Ruffolo, C.; et al. Short-Chain Fatty Acids and Human Health: From Metabolic Pathways to Current Therapeutic Implications. Life 2024, 14, 559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holscher, H.D. Dietary Fiber and Prebiotics and the Gastrointestinal Microbiota. Gut Microbes 2017, 8, 172–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cantu-Jungles, T.M.; Agamennone, V.; Van Den Broek, T.J.; Schuren, F.H.J.; Hamaker, B. Systematically-Designed Mixtures Outperform Single Fibers for Gut Microbiota Support. Gut Microbes 2025, 17, 2442521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuncil, Y.E.; Nakatsu, C.H.; Kazem, A.E.; Arioglu-Tuncil, S.; Reuhs, B.; Martens, E.C.; Hamaker, B.R. Delayed Utilization of Some Fast-Fermenting Soluble Dietary Fibers by Human Gut Microbiota When Presented in a Mixture. J. Funct. Foods 2017, 32, 347–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawicki, C.M.; Livingston, K.A.; Obin, M.; Roberts, S.B.; Chung, M.; McKeown, N.M. Dietary Fiber and the Human Gut Microbiota: Application of Evidence Mapping Methodology. Nutrients 2017, 9, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, T.; Cantu-Jungles, T.M.; Zhang, B.; Yao, T.; Lamothe, L.; Shaikh, M.; Engen, P.A.; Green, S.J.; Keshavarzian, A.; Hamaker, B.R. Dietary Fibre Responses in Microbiota Reveal Opportunity for Disease-Specific Prebiotic Approaches. Benef. Microbes 2025, 16, 497–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cantu-Jungles, T.M.; Ruthes, A.C.; El-Hindawy, M.; Moreno, R.B.; Zhang, X.; Cordeiro, L.M.C.; Hamaker, B.R.; Iacomini, M. In Vitro Fermentation of Cookeina Speciosa Glucans Stimulates the Growth of the Butyrogenic Clostridium Cluster XIVa in a Targeted Way. Carbohydr. Polym. 2018, 183, 219–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- OriginLab Corporation. OriginPro, 2023; OriginLab Corporation: Northampton, MA, USA, 2023.

- Lin, H.; Peddada, S.D. Analysis of Compositions of Microbiomes with Bias Correction. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 3514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hagberg, A.; Swart, P.J.; Schult, D.A. Exploring Network Structure, Dynamics, and Function Using NetworkX. In Proceedings of the Report Number: LA-UR-08-05495; LA-UR-08-5495; Research Org.: Los Alamos National Laboratory (LANL), 31 AD; Los Alamos National Laboratory: Los Alamos, NM, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Shannon, P.; Markiel, A.; Ozier, O.; Baliga, N.S.; Wang, J.T.; Ramage, D.; Amin, N.; Schwikowski, B.; Ideker, T. Cytoscape: A Software Environment for Integrated Models of Biomolecular Interaction Networks. Genome Res. 2003, 13, 2498–2504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S.-J.; Chen, C.-C.; Liao, H.-Y.; Lin, Y.-T.; Wu, Y.-W.; Liou, J.-M.; Wu, M.-S.; Kuo, C.-H.; Lin, C.-H. Association of Fecal and Plasma Levels of Short-Chain Fatty Acids with Gut Microbiota and Clinical Severity in Patients with Parkinson Disease. Neurology 2022, 98, e848–e858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopetuso, L.R.; Scaldaferri, F.; Petito, V.; Gasbarrini, A. Commensal Clostridia: Leading Players in the Maintenance of Gut Homeostasis. Gut Pathog. 2013, 5, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deleu, S.; Machiels, K.; Raes, J.; Verbeke, K.; Vermeire, S. Short Chain Fatty Acids and Its Producing Organisms: An Overlooked Therapy for IBD? eBioMedicine 2021, 66, 103293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakkeren, E.; Piskovsky, V.; Foster, K.R. Metabolic Ecology of Microbiomes: Nutrient Competition, Host Benefits, and Community Engineering. Cell Host Microbe 2025, 33, 790–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghoul, M.; Mitri, S. The Ecology and Evolution of Microbial Competition. Trends Microbiol. 2016, 24, 833–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernando, W.M.A.D.B.; Flint, S.H.; Ranaweera, K.K.D.S.; Bamunuarachchi, A.; Johnson, S.K.; Brennan, C.S. The Potential Synergistic Behaviour of Inter- and Intra-Genus Probiotic Combinations in the Pattern and Rate of Short Chain Fatty Acids Formation during Fibre Fermentation. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2018, 69, 144–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Galeano-Garcia, G.S.; Chen, T.; Engen, P.A.; Keshavarzian, A.; Hamaker, B.R.; Cantu-Jungles, T.M. New Insights into Synergistic Boosts in SCFA Production Across Health Conditions Induced by a Fiber Mixture. Nutrients 2025, 17, 3904. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17243904

Galeano-Garcia GS, Chen T, Engen PA, Keshavarzian A, Hamaker BR, Cantu-Jungles TM. New Insights into Synergistic Boosts in SCFA Production Across Health Conditions Induced by a Fiber Mixture. Nutrients. 2025; 17(24):3904. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17243904

Chicago/Turabian StyleGaleano-Garcia, Gabriel S., Tingting Chen, Phillip A. Engen, Ali Keshavarzian, Bruce R. Hamaker, and Thaisa M. Cantu-Jungles. 2025. "New Insights into Synergistic Boosts in SCFA Production Across Health Conditions Induced by a Fiber Mixture" Nutrients 17, no. 24: 3904. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17243904

APA StyleGaleano-Garcia, G. S., Chen, T., Engen, P. A., Keshavarzian, A., Hamaker, B. R., & Cantu-Jungles, T. M. (2025). New Insights into Synergistic Boosts in SCFA Production Across Health Conditions Induced by a Fiber Mixture. Nutrients, 17(24), 3904. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17243904