Bacterioruberin (C50 Carotenoid): Nutritional and Biomedical Potential of a Microbial Pigment

Abstract

1. Introduction

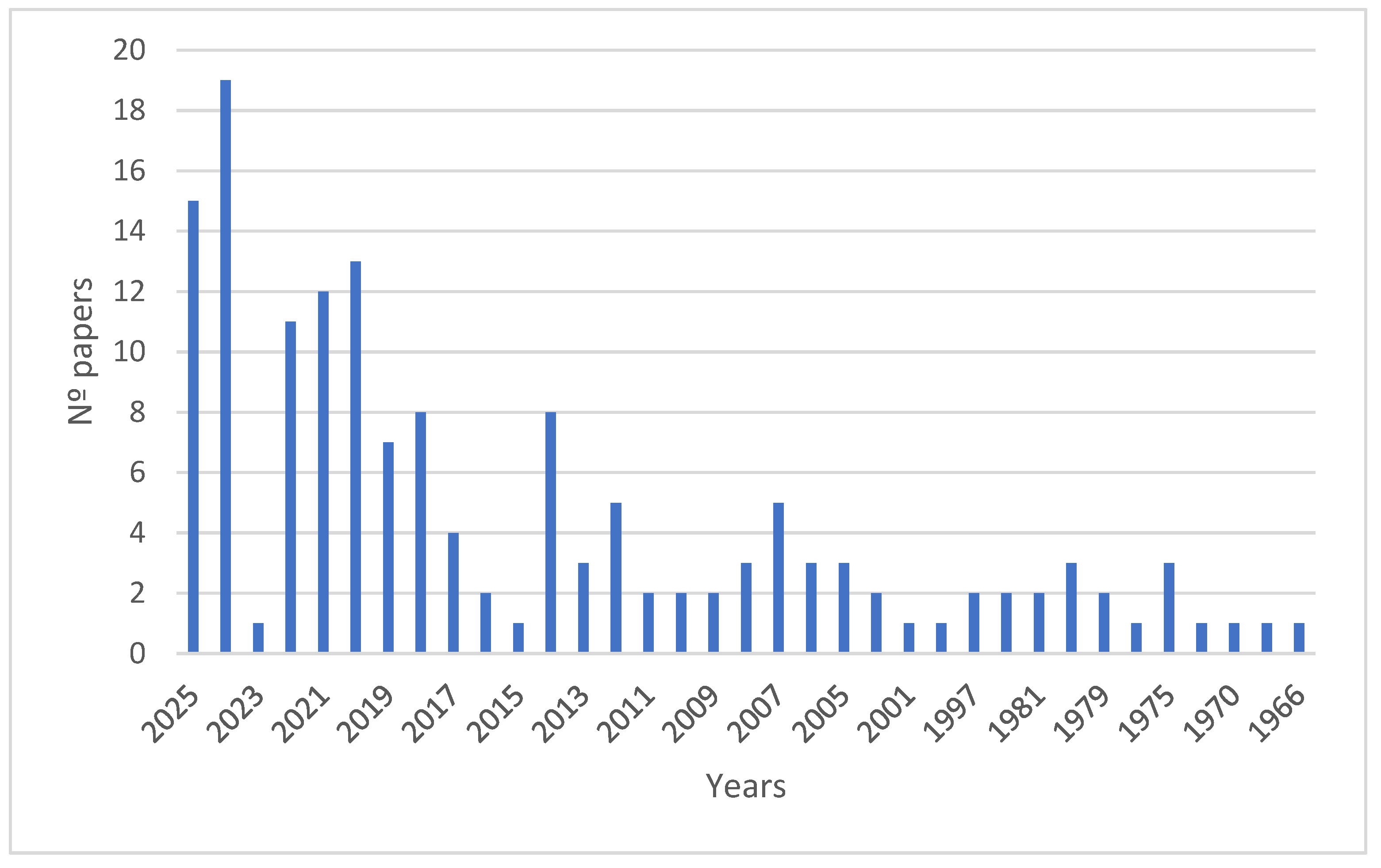

2. Materials and Methods

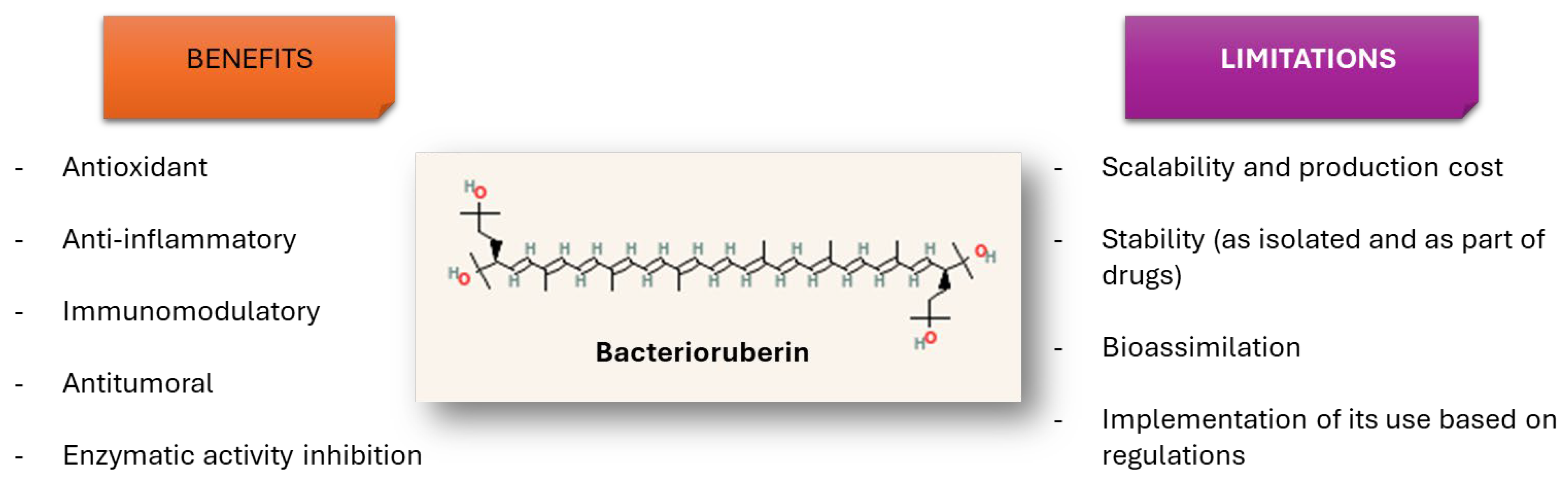

Search Strategy and Information Processing

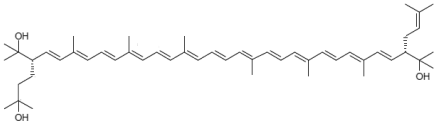

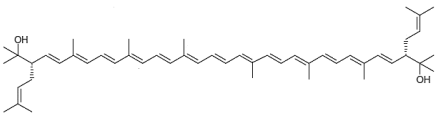

3. Description of Bacterioruberin and Closely Related Compounds

4. Potential Effects of Bacterioruberin on Human Health

4.1. Antioxidant Properties of Bacterioruberin and Bacterioruberin-Rich Extracts

4.2. Antitumoral Properties of Bacterioruberin and Bacterioruberin-Rich Extracts

4.3. Immunomodulatory/Anti-Inflammatory Activities of BR and BR-Rich Extracts

4.4. Effects of BR and BR-Rich Extracts on Key Enzymes and Proteins Involved in Human Pathologies

5. Formulations for the Delivery of Bacterioruberin as Part of Therapeutic Applications

6. Potential Food-Related Applications of Bacterioruberin

7. Conclusions

- -

- It is necessary to accurately identify the percentage that the BR represents in all the described carotenoid cell extracts to determine to what extent the observed biological activities depend on said carotenoid or on its closely related carotenoids, bisanhydrobacterioruberin (BABR), and monoanhydrobacterioruberin (MABR). This is one of the challenges that should be addressed in the short term.

- -

- It is recommended to improve the funding for basic research to elucidate the underlying molecular mechanisms that explain the effects of BR on human cells and tissues, which would guarantee faster progress in the biomedical application of this natural pigment. As the molecular mechanisms of BR become better understood regarding its interaction with different human cell and tissue types, more personalised and effective formulations could be developed.

- -

- It is important to emphasise those studies that are optimising the synthesis of nanomaterials that could act as carriers for BR to improve the release of this natural compound in the human body, thus enhancing its impact on the treated area. Some haloarchaea species can synthesise green nanoparticles (NPs) and BR; therefore, approaches that combine both compounds obtained from the same species to develop an efficient and sustainable delivery strategy would even foster green chemistry and circular economy processes that would benefit the biomedicine and biotechnology industries.

- -

- It is essential to continue with studies that allow for the (i) assessing the safety and efficacy of BR in human clinical settings (all this in alignment with health regulations; it is relevant to address BR bioavailability, metabolic reactions involved on its assimilation, or pharmacokinetics in humans or animals, thus making it possible to accurately assess potential toxicity, safety profile, or maximum tolerated doses); (ii) enabling a better transfer of knowledge between research laboratories and the sustainable pharmaceutical industry or industries related to nutraceuticals or processed food to integrate BR into their formulations; and (iii) ensuring compliance with the regulations that apply to the use of these natural compounds in therapeutic strategies.

- -

- It is relevant to make efforts to ensure the incorporation of BR into foods in a way that could guarantee its stability in real food matrices, and oversee its sensory impact and its relevance for human nutrition. In addition, it will be important to monitor its bioavailability, absorption, metabolism, and utilisation in human pathways of BR, comparing it with classical dietary carotenoids.

- -

- It could be interesting to explore other potential uses of BR in biomedicine apart from those described, depending on the biological activities already reported for BR. As an example of a recent new potential application, it has been reported that BR and selenium nanoparticles produced by Haloferax alexandrinus GUSF-1 (KF796625) show antimicrobial activity and ameliorate arsenic toxicity in human lymphocytes [67].

- -

- Finally, the feasibility of incorporating bacterioruberin into food matrices or supplements, including its stability under processing conditions and regulatory status, should be further explored.

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Martínez, G.M.; Pire, C.; Martínez-Espinosa, R.M. Hypersaline environments as natural sources of microbes with potential applications in biotechnology: The case of solar evaporation systems to produce salt in Alicante County (Spain). Curr. Res. Microb. Sci. 2022, 3, 100136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antón, J.; Peña, A.; Santos, F.; Martínez-García, M.; Schmitt-Kopplin, P.; Rosselló-Mora, R. Distribution, abundance and diversity of the extremely halophilic bacterium Salinibacter ruber. Saline Syst. 2008, 4, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oren, A. The microbiology of red brines. Adv. Appl. Microbiol. 2020, 113, 57–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edbeib, M.; Wahab, R.; Huyop, F. Halophiles: Biology adaptation their role in decontamination of hypersaline environments. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2016, 32, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oren, A. Life at high salt concentrations, intracellular KCl concentrations, and acidic proteomes. Front. Microbiol. 2013, 4, 315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, W.D. Life at low water activity. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 2004, 359, 1249–1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coker, J.A.; DasSarma, P.; Kumar, J.; Müller, J.A.; DasSarma, S. Transcriptional profiling of the model Archaeon Halobacterium sp. NRC-1: Responses to changes in salinity and temperature. Saline Syst. 2007, 3, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrei, A.S.; Banciu, H.L.; Oren, A. Living with salt: Metabolic and phylogenetic diversity of archaea inhabiting saline ecosystems. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2012, 330, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Lise, F.; Iacono, R.; Moracci, M.; Strazzulli, A.; Cobucci-Ponzano, B. Archaea as a Model System for Molecular Biology and Biotechnology. Biomolecules 2023, 13, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moopantakath, J.; Imchen, M.; Anju, V.T.; Busi, S.; Dyavaiah, M.; Martínez-Espinosa, R.M.; Kumavath, R. Bioactive molecules from haloarchaea: Scope and prospects for industrial and therapeutic applications. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1113540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giani, M.; Montero-Lobato, Z.; Garbayo, I.; Vílchez, C.; Vega, J.M.; Martínez-Espinosa, R.M. Haloferax mediterranei cells as C50 carotenoid factories. Mar. Drugs 2021, 19, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwieter, U.; Rüegg, R.; Isler, O. Synthesen in der Carotinoid-Reihe 21. Synthese von 2,2′-Diketo-spirilloxanthin (P 518) und 2,2′-Diketo-bacterioruberin [Syntheses in the carotenoid series. 21. Synthesis of 2,2′-diketo-spirilloxanthin (P 518) and 2,2′-diketo-bacterioruberin]. Helv. Chim. Acta 1966, 49, 992–996. (In German) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelly, M.; Norgård, S.; Liaaen-Jensen, S. Bacterial carotenoids. 31. C50-carotenoids 5. Carotenoids of Halobacterium salinarium, especially bacterioruberin. Acta Chem. Scand. 1970, 24, 2169–2182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chattopadhyay, M.K.; Jagannadham, M.V.; Vairamani, M.; Shivaji, S. Carotenoid Pigments of an Antarctic Psychrotrophic Bacterium Micrococcus roseus: Temperature Dependent Biosynthesis, Structure, and Interaction with Synthetic Membranes. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1997, 239, 85–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flegler, A.; Lipski, A. The C50 Carotenoid Bacterioruberin Regulates Membrane Fluidity in Pink-Pigmented Arthrobacter species. Arch. Microbiol. 2022, 204, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, T.R.; Tavares, R.S.N.; Canela-Garayoa, R.; Eras, J.; Rodrigues, M.V.N.; Neri-Numa, I.A.; Pastore, G.M.; Rosa, L.H.; Schultz, J.A.A.; Debonsi, H.M.; et al. Chemical Characterization and Biotechnological Applicability of Pigments Isolated from Antarctic Bacteria. Mar. Biotechnol. 2019, 21, 416–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kushwaha, S.C.; Kramer, J.K.G.; Kates, M. Isolation and Characterization of C50-Carotenoid Pigments and Other Polar Isoprenoids from Halobacterium cutirubrum. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1975, 398, 303–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kushwaha, S.C.; Kates, M. Studies of the Biosynthesis of C50 Carotenoids in Halobacterium cutirubrum. Can. J. Microbiol. 1979, 25, 1292–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giani, M.; Garbayo, I.; Vílchez, C.; Martínez-Espinosa, R.M. Haloarchaeal Carotenoids: Healthy Novel Compounds from Extreme Environments. Mar. Drugs 2019, 17, 524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giani, M.; Martínez-Espinosa, R.M. Carotenoids as a Protection Mechanism against Oxidative Stress in Haloferax mediterranei. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, C.P.; Leuko, S.; Coyle, C.M.; Walter, M.R.; Burns, B.P.; Neilan, B.A. Carotenoid analysis of halophilic archaea by resonance Raman spectroscopy. Astrobiology 2007, 7, 631–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palanisamy, M.; Ramalingam, S. Microbial Bacterioruberin: A Comprehensive Review. Indian J. Microbiol. 2024, 64, 1477–1501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giani, M.; Pire, C.; Martínez-Espinosa, R.M. Bacterioruberin: Biosynthesis, Antioxidant Activity, and Therapeutic Applications in Cancer and Immune Pathologies. Mar. Drugs 2024, 22, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giani, M.; Valdés, E.; Miralles-Robledillo, J.M.; Martínez, G.; Pire, C.; Martínez-Espinosa, R.M. A New Era for Using Natural Pigments: The Case of the C50 Carotenoid Called Bacterioruberin. Biotechnol. Appl. Biochem. 2025; Online ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kesbiç, F.I.; Gültepe, N. C50 carotenoids extracted from Haloterrigena thermotolerans strain K15: Antioxidant potential and identification. Folia Microbiol. 2022, 67, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Hamad Bouhamed, S.; Chaari, M.; Baati, H.; Zouari, S.; Ammar, E. Extreme halophilic Archaea: Halobacterium salinarum carotenoids characterization and antioxidant properties. Heliyon 2024, 10, e36832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahmohammadi, H.R.; Asgarani, E.; Terato, H.; Saito, T.; Ohyama, Y.; Gekko, K.; Yamamoto, O.; Ide, H. Protective Roles of Bacterioruberin and Intracellular KCl in the Resistance of Halobacterium salinarium against DNA-Damaging Agents. J. Radiat. Res. 1998, 39, 251–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Sayed, W.S.; Takaichi, S.; Saida, H.; Kamekura, M.; Abu-Shady, M.; Seki, H.; Kuwabara, T. Effects of light and low oxygen tension on pigment biosynthesis in Halobacterium salinarum, revealed by a novel method to quantify both retinal and carotenoids. Plant Cell Physiol. 2002, 43, 379–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yatsunami, R.; Ando, A.; Yang, Y.; Takaichi, S.; Kohno, M.; Matsumura, Y.; Ikeda, H.; Fukui, T.; Nakasone, K.; Fujita, N.; et al. Identification of carotenoids from the extremely halophilic archaeon Haloarcula japonica. Front. Microbiol. 2014, 5, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serino, I.; Squillaci, G.; Errichiello, S.; Carbone, V.; Baraldi, L.; La Cara, F.; Morana, A. Antioxidant Capacity of Carotenoid Extracts from the Haloarchaeon Halorhabdus utahensis. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 1840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calegari-Santos, R.; Diogo, R.A.; Fontana, J.D.; Bonfim, T.M. Carotenoid Production by Halophilic Archaea Under Different Culture Conditions. Curr. Microbiol. 2016, 72, 641–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kesbiç, F.I.; Gültepe, N. Carotenoid Characterization, Fatty Acid Profiles, and Antioxidant Activities of Haloarchaeal Extracts. J. Basic Microbiol. 2023, 64, e2300330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Souza, S.E.; Altekar, W.; D’Souza, S.F. Adaptive response of Haloferax mediterranei to low concentrations of NaCl (<20%) in the growth medium. Arch. Microbiol. 1997, 168, 68–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giani, M.; Gervasi, L.; Loizzo, M.R.; Martínez-Espinosa, R.M. Carbon Source Influences Antioxidant, Antiglycemic, and Antilipidemic Activities of Haloferax mediterranei Carotenoid Extracts. Mar. Drugs 2022, 20, 659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, C.J.; Ku, K.L.; Lee, M.H.; Su, N.W. Influence of nutritive factors on C50 carotenoids production by Haloferax mediterranei ATCC 33500 with two-stage cultivation. Bioresour. Technol. 2010, 101, 6487–6493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Villegas, P.; Vigara, J.; Vila, M.; Varela, J.; Barreira, L.; Léon, R. Antioxidant, Antimicrobial, and Bioactive Potential of Two New Haloarchaeal Strains Isolated from Odiel Salterns (Southwest Spain). Biology 2020, 9, 298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandelli, F.; Miranda, V.S.; Rodrigues, E.; Mercadante, A.Z. Identification of Carotenoids with High Antioxidant Capacity Produced by Extremophile Microorganisms. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2012, 28, 1781–1790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado-Garcia, M.; Gómez-Secundino, O.; Rodríguez, J.A.; Mateos-Díaz, J.C.; Muller-Santos, M.; Aguilar, C.N.; Camacho- Ruiz, R.M. Identification, Antioxidant Capacity, and Matrix Metallopeptidase 9 (MMP-9) In Silico Inhibition of Haloarchaeal Carotenoids from Natronococcus sp. and Halorubrum tebenquichense. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 2344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz-Angeles, N.A.M.; Devanadera, M.K.P.; Watanabe, K.; Bennett, R.M.; Aki, T.; Dedeles, G.R. Singlet oxygen antioxidant capacity of carotenoids from Halorubrum salinarum. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2025, 78, ovaf085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kottemann, M.; Kish, A.; Iloanusi, C.; Bjork, S.; DiRuggiero, J. Physiological responses of the halophilic archaeon Halobacterium sp. strain NRC1 to desiccation and gamma irradiation. Extremophiles 2005, 9, 219–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, J.; Cui, H.-L. In Vitro Antioxidant, Antihemolytic, and Anticancer Activity of the Carotenoids from Halophilic Archaea. Curr. Microbiol. 2018, 75, 266–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ávila-Román, J.; Gómez-Villegas, P.; de Carvalho, C.C.C.R.; Vigara, J.; Motilva, V.; León, R.; Talero, E. Up-Regulation of the Nrf2/HO-1 Antioxidant Pathway in Macrophages by an Extract from a New Halophilic Archaea Isolated in Odiel Saltworks. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, Y.; Li, C.; Su, W.; Sun, Z.; Gao, S.; Xie, W.; Zhang, B.; Sui, L. Carotenoids in Skin Photoaging: Unveiling Protective Effects, Molecular Insights, and Safety and Bioavailability Frontiers. Antioxidants 2025, 14, 577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Cho, E.S.; Hwang, C.Y.; Cao, L.; Kim, M.B.; Lee, S.G.; Seo, M.J. Bacterioruberin extract from Haloarchaea Haloferax marinum: Component identification, antioxidant activity and anti-atrophy effect in LPS-treated C2C12 myotubes. Microb. Biotechnol. 2024, 17, e70009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zalazar, L.; Pagola, P.; Miró, M.V.; Churio, M.S.; Cerletti, M.; Martínez, C.; Iniesta-Cuerda, M.; Soler, A.J.; Cesari, A.; De Castro, R. Bacterioruberin extracts from a genetically modified hyperpigmented Haloferax volcanii strain: Antioxidant activity and bioactive properties on sperm cells. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2019, 126, 796–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbes, M.; Baati, H.; Guermazi, S.; Messina, C.; Santulli, A.; Gharsallah, N.; Ammar, E. Biological Properties of Carotenoids Extracted from Halobacterium halobium Isolated from a Tunisian Solar Saltern. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2013, 13, 255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegazy, G.E.; Abu-Serie, M.M.; Abo-Elela, G.M.; Ghozlan, H.; Sabry, S.A.; Soliman, N.A.; Abdel-Fattah, Y.R. In Vitro Dual (Anticancer and Antiviral) Activity of the Carotenoids Produced by Haloalkaliphilic Archaeon Natrialba sp. M6. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 5986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giani, M.; Montoyo-Pujol, Y.G.; Peiró, G.; Martínez-Espinosa, R.M. Haloarchaeal Carotenoids Exert an in Vitro Antiproliferative Effect on Human Breast Cancer Cell Lines. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 7148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Espinosa, R.M. Halocins and C50 Carotenoids from Haloarchaea: Potential Natural Tools against Cancer. Mar. Drugs 2024, 22, 448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahbazi, S.; Zargar, M.; Zolfaghari, M.R.; Amoozegar, M.A. Carotenoid pigment of Halophilic archaeon Haloarcula sp. A15 induces apoptosis of breast cancer cells. Cell Biochem. Funct. 2023, 41, 344–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baeza-Morales, A.; Pascual-García, S.; Martínez-Peinado, P.; Navarro-Sempere, A.; Segovia, Y.; Medina-García, M.; Pujalte-Satorre, C.; García, M.M.; Martínez-Espinosa, R.M.; Sempere-Ortells, J.M. Bacterioruberin extract from Haloferax mediterranei induces apoptosis and cell cycle arrest in myeloid leukaemia cell lines. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 23485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higa, L.H.; Schilrreff, P.; Briski, A.M.; Jerez, H.E.; De Farias, M.A.; Villares Portugal, R.; Romero, E.L.; Morilla, M.J. Bacterioruberin from Haloarchaea plus Dexamethasone in Ultra-Small Macrophage-Targeted Nanoparticles as Potential Intestinal Repairing Agent. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2020, 191, 110961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lizama, C.; Romero-Parra, J.; Andrade, D.; Riveros, F.; Bórquez, J.; Ahmed, S.; Venegas-Salas, L.; Cabalín, C.; Simirgiotis, M.J. Analysis of Carotenoids in Haloarchaea Species from Atacama Saline Lakes by High Resolution UHPLC-Q-Orbitrap-Mass Spectrometry: Antioxidant Potential and Biological Effect on Cell Viability. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tisserand, J.C.; Pellay, F.X.; Lecland, N.; Fontbonne, A.; Giraud, F.; Perrier, E.; Trompezinski, S.; Benoit, I. Antioxidative and chaperone-like activities of a bacterioruberin-rich extract: An innovative approach to protect the skin proteome. Int. J. Cosmet. Sci. 2025; Online ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desai, A.; Ray, S. Haloalkaliphilic Archaea as Sources of Carotenoids: Ecological Distribution, Biosynthesis and Therapeutic Applications. J. Basic Microbiol. 2025, 23, e70084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torregrosa-Crespo, J.; Galiana, C.P.; Martínez-Espinosa, R.M. Biocompounds from Haloarchaea and Their Uses in Biotechnology. In Archaea—New Biocatalysts, Novel Pharmaceuticals and Various Biotechnological Applications; InTech.: Houston, TX, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Morilla, M.J.; Ghosal, K.; Romero, E.L. More Than Pigments: The Potential of Astaxanthin and Bacterioruberin-Based Nanomedicines. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 1828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caimi, A.T.; Yasynska, O.; Rivas Rojas, P.C.; Romero, E.L.; Morilla, M.J. Improved stability and biological activity of bacterioruberin in nanovesicles. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2022, 77, 103896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juncal, M.A.; Caputo, E.N.; Rivas Rojas, P.C.; Morilla, M.J.; Romero, E.L.; Higa, L.H.; Altube, M.J. Inhalable nanocapsules for lung delivery of Pirfenidone and Bacterioruberin: Modulating macrophages to target pulmonary fibrosis. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2025, 217, 114893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González Epelboim, V.R.D.; Lamas, D.G.; Huck-Iriart, C.; Caputo, E.N.; Altube, M.J.; Jerez, H.E.; Simioni, Y.R.; Ghosal, K.; Morilla, M.J.; Higa, L.H.; et al. Nebulized Bacterioruberin/Astaxanthin-Loaded Nanovesicles: Antitumoral Activity and Beyond. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 8607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simioni, Y.R.; Ricatti, F.; Salvay, A.G.; Jerez, H.E.; Schilrreff, P.; Romero, E.L.; Morilla, M.J. Activity of hydrogel-vitamin D3 /bacterioruberin nanoparticles on imiquimod-induced fibroblasts-keratinocytes spheroids. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2024, 97, 105738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simioni, Y.R.; Usseglio, N.; Butassi, E.; Altube, M.J.; Higa, L.H.; Romero, E.L.; Schilrreff, P.; Morilla, M.J. Biocompatibility, anti-inflammatory, wound healing, and antifungal activity of macrophage targeted-bacterioruberin-vitamin D3 loaded nanoparticles. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2025, 105, 106661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molaeirad, A.; Janfaza, S.; Karimi-Fard, A.; Mahyad, B. Photocurrent generation by adsorption of two main pigments of Halobacterium salinarum on TiO2 nanostructured electrode. Biotechnol. Appl. Biochem. 2015, 62, 121–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Metwally, R.A.; El Nady, J.; Ebrahim, S.; El Sikaily, A.; El-Sersy, N.A.; Sabry, S.A.; Ghozlan, H.A. Biosynthesis, characterization and optimization of TiO2 nanoparticles by novel marine halophilic Halomonas sp. RAM2: Application of natural dye-sensitized solar cells. Microb. Cell Fact. 2023, 22, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yachai, M. Carotenoid Production by Halophilic Archaea and Its Applications. Ph.D. Thesis, Prince of Songkla University, Songkhla, Thailand, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Reddy, R.; Xavier, K.A.M.; Balange, A.K.; Kumar, H.S.; Kumar Panda, S.; Nayak, B.B. Antioxidative effects of haloarchaeal bacterioruberin in pangasius emulsion sausage during refrigerated storage. J. Food Sci. 2025, 90, e70045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, L.J.; Burgess, J.R.; Stochelski, M.A.; Kuczek, T. Amounts of artificial food dyes and added sugars in foods and sweets commonly consumed by children. Clin. Pediatr. 2015, 54, 309–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sajjad, W.; Muhammad, M.; Bukhari, S.M.A.U.S.; Abbasi, S.W.; Mohamad, O.A.A.; Liu, Y.H.; Li, W.J. Application of bacterioruberin from Arthrobacter sp. isolated from Xinjiang desert to extend the shelf-life of fruits during postharvest storage. Food Chem. 2025, 10, 100239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mussagy, C.U.; Caicedo-Paz, A.V.; Farias, F.O.; de Souza Mesquita, L.M.; Giuffrida, D.; Dufossé, L. Microbial bacterioruberin: The new C50 carotenoid player in food industries. Food Microbiol. 2024, 124, 104623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvares, J.; Gaonkar, S.; D’costa, A.; Shyama, S.K.; Furtado, I. Antimicrobial potential and alleviation of arsenic toxicity in human lymphocytes by bacterioruberin and selenium nanoparticles from Haloferax alexandrinus GUSF-1 (KF796625). Discov. Appl. Sci. 2025, 7, 919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Common Name Chemical Formula | Chemical Structure (Stereoisomers) |

|---|---|

| Bacterioruberin C50H76O4 |  (2S,2′S)-2,2′-bis(3-hydroxy-3-methylbutyl)-3,4,3′,4′-tetradehydro-1,2,1′,2′-tetrahydro-γ,γ-carotene-1,1′-diol |

| Monoanhydrobacterioruberin C50H74O3 |  (3S,4E,6E,8E,10E,12E,14E,16E,18E,20E,22E,24E,26E,28E,30S)-30-(2-hydroxypropan-2-yl)-2,6,10,14,19,23,27,33-octamethyl-3-(3-methylbut-2-en-1-yl)tetratriaconta-4,6,8,10,12,14,16,18,20,22,24,26,28-tridecaene-2,33-diol |

| Bisanhydrobacterioruberin C50H72O2 |  (3S,4E,6E,8E,10E,12E,14E,16E,18E,20E,22E,24E,26E,28E,30S)-2,6,10,14,19,23,27,31-octamethyl-3,30-bis(3-methylbut-2-en-1-yl)dotriaconta-4,6,8,10,12,14,16,18,20,22,24,26,28-tridecaene-2,31-diol |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Martínez-Espinosa, R.M. Bacterioruberin (C50 Carotenoid): Nutritional and Biomedical Potential of a Microbial Pigment. Nutrients 2025, 17, 3899. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17243899

Martínez-Espinosa RM. Bacterioruberin (C50 Carotenoid): Nutritional and Biomedical Potential of a Microbial Pigment. Nutrients. 2025; 17(24):3899. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17243899

Chicago/Turabian StyleMartínez-Espinosa, Rosa María. 2025. "Bacterioruberin (C50 Carotenoid): Nutritional and Biomedical Potential of a Microbial Pigment" Nutrients 17, no. 24: 3899. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17243899

APA StyleMartínez-Espinosa, R. M. (2025). Bacterioruberin (C50 Carotenoid): Nutritional and Biomedical Potential of a Microbial Pigment. Nutrients, 17(24), 3899. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17243899