Lifestyle Patterns and Incidence of Cardiovascular Diseases, Cancer, Respiratory Diseases, and Type 2 Diabetes: A Large-Scale Prospective Cohort Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

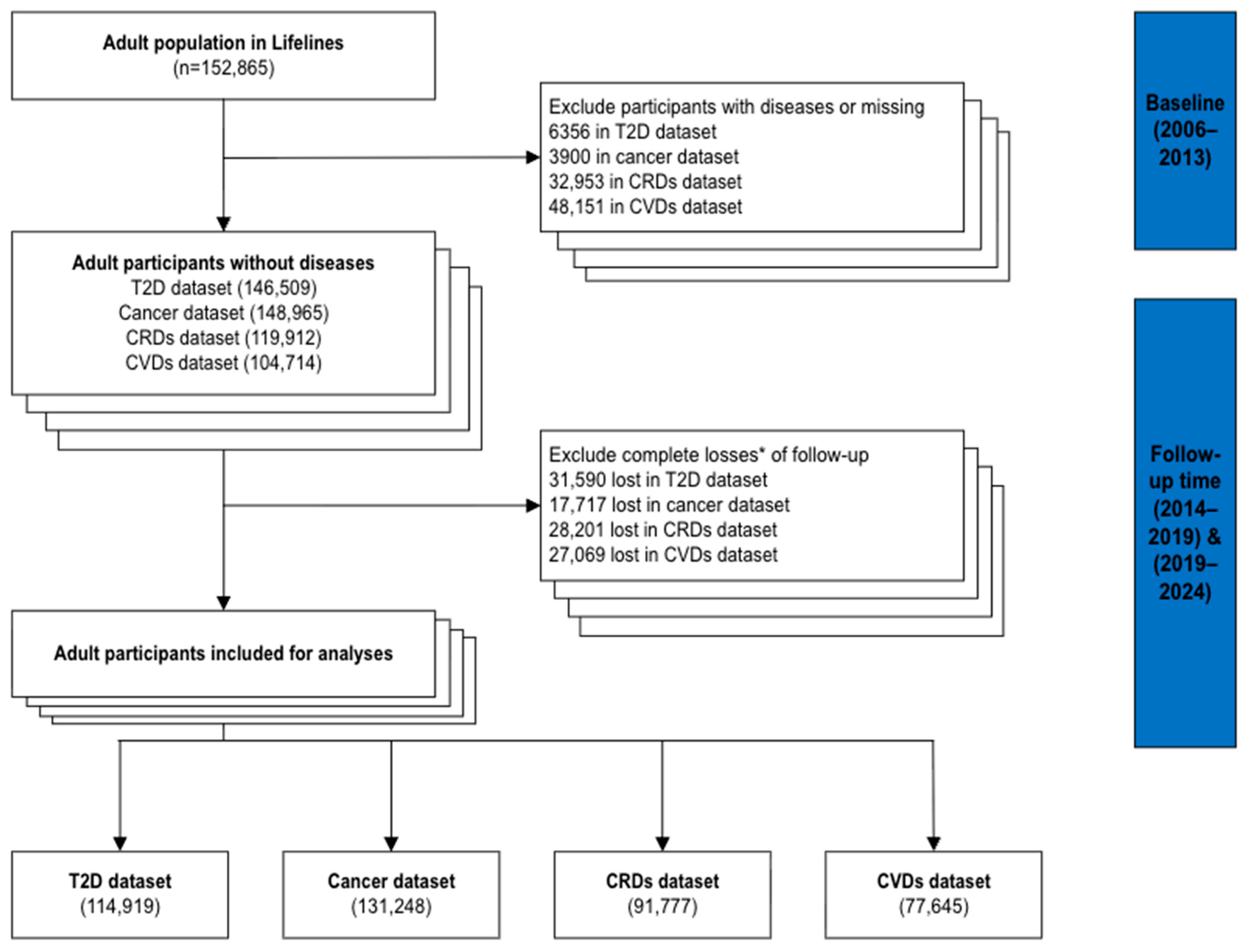

2.1. Study Design and Participants

2.2. Exposures and Outcomes

2.3. Confounders

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Study Population and Descriptive Statistics

3.2. Associations Between LPs and Disease Risk

3.3. Linearity of Associations Between Lifestyle Summation Scores and Disease Risk

3.4. Sensitivity Analyses

4. Discussion

4.1. Association Between LPs and Disease Risk

4.2. Linearity Between Lifestyle Summation Scores and Disease Risk

4.3. Insights for Implementation: Comparing LPs and Lifestyle Summation Scores

4.4. Limitations and Strengths

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CVDs | Cardiovascular diseases |

| CRDs | Chronic respiratory diseases |

| T2D | Type 2 diabetes |

| LPs | Lifestyle patterns |

| NCDs | Non-communicable diseases |

| COPD | Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease |

| LCA | Latent class analysis |

| FEV1 | Forced expiratory volume in one second |

| FVC | Forced vital capacity |

| MICE | Multivariate imputation by chained equations |

| SHR | Sub-hazard ratios |

| HR | Hazard ratios |

| CI | Confidence interval |

| SD | Standard deviation |

| PCA | Principal component analysis |

| BACCs | Branched-chain amino acids |

| MHBC | Multiple health behaviour change |

References

- GBD 2015 Mortality and Causes of Death Collaborators. Global, regional, and national life expectancy, all-cause mortality, and cause-specific mortality for 249 causes of death, 1980–2015: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet 2016, 388, 1459–1544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. The Top 10 Causes of Death. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/the-top-10-causes-of-death (accessed on 19 November 2024).

- Mattiuzzi, C.; Lippi, G. Current Cancer Epidemiology. J. Epidemiol. Glob. Health 2019, 9, 217–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Cardiovascular Diseases (CVDs). Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/cardiovascular-diseases-(cvds) (accessed on 19 November 2024).

- GBD Chronic Respiratory Disease Collaborators. Prevalence and attributable health burden of chronic respiratory diseases, 1990-2017: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet Respir. Med. 2020, 8, 585–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Federation, I.D. IDF Diabetes Atlas, 10th ed. Available online: https://www.diabetesatlas.org (accessed on 11 November 2024).

- World Health Organizaion. Noncommunicable Diseases. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/noncommunicable-diseases?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 19 November 2024).

- Lifestyle Medicine Global Alliance. Lifestyle Medicine. Available online: https://lifestylemedicineglobal.org/lifestyle-medicine (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Nyberg, S.T.; Batty, G.D.; Pentti, J.; Virtanen, M.; Alfredsson, L.; Fransson, E.I.; Goldberg, M.; Heikkila, K.; Jokela, M.; Knutsson, A.; et al. Obesity and loss of disease-free years owing to major non-communicable diseases: A multicohort study. Lancet Public Health 2018, 3, e490–e497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Billingsley, M. New advice on physical activity aims to prevent chronic disease from early years. BMJ 2011, 343, d4457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budreviciute, A.; Damiati, S.; Sabir, D.K.; Onder, K.; Schuller-Goetzburg, P.; Plakys, G.; Katileviciute, A.; Khoja, S.; Kodzius, R. Management and Prevention Strategies for Non-communicable Diseases (NCDs) and Their Risk Factors. Front. Public Health 2020, 8, 574111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, I.A.; Jenkins, C.R.; Salvi, S.S. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in never-smokers: Risk factors, pathogenesis, and implications for prevention and treatment. Lancet Respir. Med. 2022, 10, 497–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ai, S.; Zhang, J.; Zhao, G.; Wang, N.; Li, G.; So, H.C.; Liu, Y.; Chau, S.W.; Chen, J.; Tan, X.; et al. Causal associations of short and long sleep durations with 12 cardiovascular diseases: Linear and nonlinear Mendelian randomization analyses in UK Biobank. Eur. Heart J. 2021, 42, 3349–3357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, R.; Sutradhar, R.; Yao, Z.; Wodchis, W.P.; Rosella, L.C. Smoking, drinking, diet and physical activity-modifiable lifestyle risk factors and their associations with age to first chronic disease. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2020, 49, 113–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, Z.-Z.; Lu, Q.; Zhang, Y.-B.; Shu, Z.; Lai, Y.-W.; Ma, M.-N.; Xia, P.-F.; Geng, T.-T.; Chen, J.-X.; Li, Y.; et al. Associations of Combined Healthy Lifestyle Factors with Risks of Diabetes, Cardiovascular Disease, Cancer, and Mortality Among Adults with Prediabetes: Four Prospective Cohort Studies in China, the United Kingdom, and the United States. Engineering 2023, 22, 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weitzman, E.R.; Chen, Y.Y. The co-occurrence of smoking and drinking among young adults in college: National survey results from the United States. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2005, 80, 377–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cockerham, W.C. Health lifestyle theory and the convergence of agency and structure. J. Health Soc. Behav. 2005, 46, 51–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, D.; Rogers, K.; van der Ploeg, H.; Stamatakis, E.; Bauman, A.E. Traditional and Emerging Lifestyle Risk Behaviors and All-Cause Mortality in Middle-Aged and Older Adults: Evidence from a Large Population-Based Australian Cohort. PLoS Med. 2015, 12, e1001917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slattery, M.L.; Potter, J.D. Physical activity and colon cancer: Confounding or interaction? Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2002, 34, 913–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Q.; Ogaz-Gonzalez, R.; Du, Y.; Duan, M.J.; Lunter, G.; Corpeleijn, E. Non-random aggregations of healthy and unhealthy lifestyles and their population characteristics-pattern recognition in a large population-based cohort. Arch. Public Health 2025, 83, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro Silvera, S.A.; Mayne, S.T.; Risch, H.A.; Gammon, M.D.; Vaughan, T.; Chow, W.H.; Dubin, J.A.; Dubrow, R.; Schoenberg, J.; Stanford, J.L.; et al. Principal component analysis of dietary and lifestyle patterns in relation to risk of subtypes of esophageal and gastric cancer. Ann. Epidemiol. 2011, 21, 543–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, M.J.; Dekker, L.H.; Carrero, J.J.; Navis, G. Lifestyle patterns and incident type 2 diabetes in the Dutch lifelines cohort study. Prev. Med. Rep. 2022, 30, 102012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manninen, S.; Tilles-Tirkkonen, T.; Aittola, K.; Mannikko, R.; Karhunen, L.; Kolehmainen, M.; Schwab, U.; Lindstrom, J.; Lakka, T.; Pihlajamaki, J.; et al. Associations of Lifestyle Patterns with Glucose and Lipid Metabolism in Finnish Adults at Increased Risk of Type 2 Diabetes. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2024, 68, e2300338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mourouti, N.; Mavrogianni, C.; Mouratidou, T.; Liatis, S.; Valve, P.; Rurik, I.; Torzsa, P.; Cardon, G.; Bazdarska, Y.; Iotova, V.; et al. The Association of Lifestyle Patterns with Prediabetes in Adults from Families at High Risk for Type 2 Diabetes in Europe: The Feel4Diabetes Study. Nutrients 2023, 15, 3155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnermann, M.E.; Schulz, C.A.; Herder, C.; Alexy, U.; Nothlings, U. A lifestyle pattern during adolescence is associated with cardiovascular risk markers in young adults: Results from the DONALD cohort study. J. Nutr. Sci. 2021, 10, e92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Li, R.; Xie, J.; Chen, J.; Liu, S.; Pan, A.; Liu, G. Associations of socioeconomic status and healthy lifestyle with incident early-onset and late-onset dementia: A prospective cohort study. Lancet Healthy Longev. 2023, 4, e693–e702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, J.; Fu, R.; Yuan, T.; Brenner, H.; Hoffmeister, M. Lifestyle scores and their potential to estimate the risk of multiple non-communicable disease-related endpoints: A systematic review. BMC Public Health 2025, 25, 293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAloney, K.; Graham, H.; Law, C.; Platt, L. A scoping review of statistical approaches to the analysis of multiple health-related behaviours. Prev. Med. 2013, 56, 365–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S.L.F.; Braaten, T.; Borch, K.B.; Ferrari, P.; Sandanger, T.M.; Nost, T.H. Combined Lifestyle Behaviors and the Incidence of Common Cancer Types in the Norwegian Women and Cancer Study (NOWAC). Clin. Epidemiol. 2021, 13, 721–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aleksandrova, K.; Pischon, T.; Jenab, M.; Bueno-de-Mesquita, H.B.; Fedirko, V.; Norat, T.; Romaguera, D.; Knuppel, S.; Boutron-Ruault, M.C.; Dossus, L.; et al. Combined impact of healthy lifestyle factors on colorectal cancer: A large European cohort study. BMC Med. 2014, 12, 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lelong, H.; Blacher, J.; Baudry, J.; Adriouch, S.; Galan, P.; Fezeu, L.; Hercberg, S.; Kesse-Guyot, E. Combination of Healthy Lifestyle Factors on the Risk of Hypertension in a Large Cohort of French Adults. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Buuren, S.; Groothuis-Oudshoorn, K. mice: Multivariate Imputation by Chained Equations in R. J. Stat. Softw. 2011, 45, 1–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klijs, B.; Scholtens, S.; Mandemakers, J.J.; Snieder, H.; Stolk, R.P.; Smidt, N. Representativeness of the LifeLines Cohort Study. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0137203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholtens, S.; Smidt, N.; Swertz, M.A.; Bakker, S.J.; Dotinga, A.; Vonk, J.M.; van Dijk, F.; van Zon, S.K.; Wijmenga, C.; Wolffenbuttel, B.H.; et al. Cohort Profile: LifeLines, a three-generation cohort study and biobank. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2015, 44, 1172–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Elm, E.; Altman, D.G.; Egger, M.; Pocock, S.J.; Gotzsche, P.C.; Vandenbroucke, J.P.; Initiative, S. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies. Prev. Med. 2007, 45, 247–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirshkowitz, M.; Whiton, K.; Albert, S.M.; Alessi, C.; Bruni, O.; DonCarlos, L.; Hazen, N.; Herman, J.; Katz, E.S.; Kheirandish-Gozal, L.; et al. National Sleep Foundation’s sleep time duration recommendations: Methodology and results summary. Sleep Health 2015, 1, 40–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinke, P.C.; Corpeleijn, E.; Dekker, L.H.; Jacobs, D.R., Jr.; Navis, G.; Kromhout, D. Development of the food-based Lifelines Diet Score (LLDS) and its application in 129,369 Lifelines participants. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2018, 72, 1111–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brouwer-Brolsma, E.M.; Perenboom, C.; Sluik, D.; van de Wiel, A.; Geelen, A.; Feskens, E.J.; de Vries, J.H. Development and external validation of the ‘Flower-FFQ’: A FFQ designed for the Lifelines Cohort Study. Public Health Nutr. 2022, 25, 225–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monteiro, C.; Cannon, G.; Levy, R.; Moubarac, J.-C.; Jaime, P.; Parra, A. NOVA. The star shines bright. World Nutr. 2016, 7, 28–38. [Google Scholar]

- Byambasukh, O. Physical Activity and Cardiometabolic Health: Focus on Domain-Specific Associations of Physical Activity over the Life Course. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Groningen, Groningen, The Netherlands, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Rosmalen, J.G.; Bos, E.H.; de Jonge, P. Validation of the Long-term Difficulties Inventory (LDI) and the List of Threatening Experiences (LTE) as measures of stress in epidemiological population-based cohort studies. Psychol. Med. 2012, 42, 2599–2608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nieboer, A.; Lindenberg, S.; Boomsma, A.; Bruggen, A.C.V. Dimensions Of Well-Being And Their Measurement: The Spf-Il Scale. Soc. Indic. Res. 2005, 73, 313–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, S.; Katzmarzyk, P.T.; Gomes, T.N.; Borges, A.; Santos, D.; Souza, M.; dos Santos, F.K.; Chaves, R.N.; Champagne, C.M.; Barreira, T.V.; et al. Profiling physical activity, diet, screen and sleep habits in Portuguese children. Nutrients 2015, 7, 4345–4362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weller, B.E.; Bowen, N.K.; Faubert, S.J. Latent Class Analysis: A Guide to Best Practice. J. Black Psychol. 2020, 46, 287–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amini, M.; Bashirova, D.; Prins, B.P.; Corpeleijn, E.; LifeLines Cohort, S.; Bruinenberg, M.; Franke, L.; Harst, P.V.; Navis, G.; Wolffenbuttel, B.H.; et al. Eosinophil Count Is a Common Factor for Complex Metabolic and Pulmonary Traits and Diseases: The LifeLines Cohort Study. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0168480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortes-Ibanez, F.O.; van Pinxteren, B.; Sijtsma, A.; Bruggink, A.; Sidorenkov, G.; van der Vegt, B.; de Bock, G.H. The validity of self-reported cancer in a population-based cohort compared to that in formally registered sources. Cancer Epidemiol. 2022, 81, 102268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niebuur, J.; Vonk, J.M.; Du, Y.; de Bock, G.H.; Lunter, G.; Krabbe, P.F.M.; Alizadeh, B.Z.; Snieder, H.; Smidt, N.; Boezen, M.; et al. Lifestyle factors related to prevalent chronic disease multimorbidity: A population-based cross-sectional study. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0287263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van der Ende, M.Y.; Hartman, M.H.; Hagemeijer, Y.; Meems, L.M.; de Vries, H.S.; Stolk, R.P.; de Boer, R.A.; Sijtsma, A.; van der Meer, P.; Rienstra, M.; et al. The LifeLines Cohort Study: Prevalence and treatment of cardiovascular disease and risk factors. Int. J. Cardiol. 2017, 228, 495–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD). Available online: https://www.who.int/standards/classifications/classification-of-diseases (accessed on 20 November 2024).

- Nummela, O.P.; Sulander, T.T.; Heinonen, H.S.; Uutela, A.K. Self-rated health and indicators of SES among the ageing in three types of communities. Scand. J. Public Health 2007, 35, 39–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daw, J.; Margolis, R.; Wright, L. Emerging Adulthood, Emergent Health Lifestyles: Sociodemographic Determinants of Trajectories of Smoking, Binge Drinking, Obesity, and Sedentary Behavior. J. Health Soc. Behav. 2017, 58, 181–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Buuren, S. Multiple imputation of discrete and continuous data by fully conditional specification. Stat. Methods Med. Res. 2007, 16, 219–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fine, J.P.; Gray, R.J. A Proportional Hazards Model for the Subdistribution of a Competing Risk. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1999, 94, 496–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Vedia, J.; Llop, D.; Rodriguez-Calvo, R.; Plana, N.; Amigo, N.; Rosales, R.; Esteban, Y.; Girona, J.; Masana, L.; Ibarretxe, D. Serum branch-chained amino acids are increased in type 2 diabetes and associated with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2023, 22, 249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekelund, U.; Steene-Johannessen, J.; Brown, W.J.; Fagerland, M.W.; Owen, N.; Powell, K.E.; Bauman, A.; Lee, I.M.; Lancet Physical Activity Series 2 Executive Committee; Lancet Sedentary Behaviour Working Group. Does physical activity attenuate, or even eliminate, the detrimental association of sitting time with mortality? A harmonised meta-analysis of data from more than 1 million men and women. Lancet 2016, 388, 1302–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.H.; Yu, F.F.; Zhou, Y.H.; He, J. Association between alcohol consumption and the risk of incident type 2 diabetes: A systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2016, 103, 818–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandstrom, N.; Johansson, M.; Jekunen, A.; Andersen, H. Socioeconomic status and lifestyle patterns in the most common cancer types-community-based research. BMC Public Health 2023, 23, 1722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehm, J.; Shield, K.D.; Weiderpass, E. Alcohol consumption. A leading risk factor for cancer. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2020, 331, 109280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jang, W.; Kim, S.; Son, Y.; Kim, S.; Lee, H.; Park, J.; Lee, K.; Kang, J.; Pizzol, D.; Hwang, J.; et al. Non-Linear Association Between Physical Activities and Type 2 Diabetes in 2.4 Million Korean Population, 2009–2022: A Nationwide Representative Study. J. Korean Med. Sci. 2025, 40, e42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viner, B.; Barberio, A.M.; Haig, T.R.; Friedenreich, C.M.; Brenner, D.R. The individual and combined effects of alcohol consumption and cigarette smoking on site-specific cancer risk in a prospective cohort of 26,607 adults: Results from Alberta’s Tomorrow Project. Cancer Causes Control 2019, 30, 1313–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, R.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Lyu, J.; Li, R.; Kang, W.; Zhao, A.; Ning, Z.; Hu, Y.; Lin, X.; et al. The Joint Association of Sleep Quality and Outdoor Activity with Asthma and Allergic Rhinitis in Children: A Cross-Sectional Study in Shanghai. J. Asthma Allergy 2025, 18, 101–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, C.C.; Presseau, J.; van Allen, Z.; Schenk, P.M.; Moreto, M.; Dinsmore, J.; Marques, M.M. Effectiveness of Interventions for Changing More Than One Behavior at a Time to Manage Chronic Conditions: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Ann. Behav. Med. 2024, 58, 432–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Pan, X.F.; Chen, J.; Xia, L.; Cao, A.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, J.; Li, H.; Yang, K.; Guo, K.; et al. Combined lifestyle factors and risk of incident type 2 diabetes and prognosis among individuals with type 2 diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Diabetologia 2020, 63, 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, T.; Zhu, K.; Lu, Q.; Wan, Z.; Chen, X.; Liu, L.; Pan, A.; Liu, G. Healthy lifestyle behaviors, mediating biomarkers, and risk of microvascular complications among individuals with type 2 diabetes: A cohort study. PLoS Med. 2023, 20, e1004135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, U.J.; Choi, E.J.; Park, H.; Lee, H.A.; Park, B.; Kim, H.; Hong, Y.; Jung, S.; Park, H. The Mediating Effect of Inflammation between the Dietary and Health-Related Behaviors and Metabolic Syndrome in Adolescence. Nutrients 2022, 14, 2339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belloc, N.B.; Breslow, L. Relationship of physical health status and health practices. Prev. Med. 1972, 1, 409–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, C.C.; Presseau, J.; van Allen, Z.; Dinsmore, J.; Schenk, P.; Moreto, M.; Marques, M.M. Components of multiple health behaviour change interventions for patients with chronic conditions: A systematic review and meta-regression of randomized trials. Health Psychol. Rev. 2025, 19, 200–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| T2D Dataset | Cancer Dataset | CRDs Dataset | CVDs Dataset | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample size | 114,919 | 131,248 | 91,777 | 77,645 |

| Disease incidences | 3114 | 4685 | 4133 | 2850 |

| Incidence rate a | 321 | 511 | 603 | 485 |

| Years of follow-up | 9.3 (4.8, 10.8) | 5.9 (4.0, 10.0) | 8.5 (4.0, 10.3) | 8.7 (4.0, 10.3) |

| Age, year | 45.6 ± 12.9 | 45.4 ± 13.0 | 46.3 ± 13.0 | 45.3 ± 12.9 |

| Sex, male | 47,570 (41.4) | 54,656 (41.6) | 38,164 (41.6) | 34,024 (43.8) |

| Education attainment | ||||

| Elementary | 2799 (2.4) | 3622 (2.8) | 2245 (2.5) | 1842 (2.4) |

| Lower secondary | 29,805 (25.9) | 34,719 (26.5) | 23,863 (26.0) | 19,706 (25.4) |

| Upper secondary | 44,450 (38.7) | 50,670 (38.6) | 35,097 (38.3) | 30,010 (38.7) |

| Tertiary | 35,727 (31.1) | 39,720 (30.3) | 28,787 (31.4) | 24,720 (31.8) |

| Others | 2138 (1.9) | 2517 (1.9) | 1719 (1.9) | 1367 (1.8) |

| Net income, Euro | ||||

| lower than 1100 | 19,478 (17.0) | 22,903 (17.5) | 14,842 (16.2) | 12,736 (16.4) |

| 1100 to 1500 | 26,218 (22.8) | 29,724 (22.7) | 20,828 (22.7) | 17,715 (22.8) |

| 1500 to 1900 | 29,814 (25.9) | 33,351 (25.4) | 23,952 (26.1) | 20,305 (26.2) |

| Higher than 1900 | 23,250 (20.2) | 26,396 (20.1) | 19,191 (20.9) | 16,144 (20.8) |

| I don’t know this | 4294 (3.7) | 5014 (3.8) | 3380 (3.7) | 2843 (3.7) |

| I don’t want to tell | 11,865 (10.3) | 13,860 (10.6) | 9518 (10.4) | 7902 (10.2) |

| Partner relationships | ||||

| Married/cohabiting | 92,564 (80.6) | 105,190 (80.2) | 74,416 (81.1) | 62,477 (80.5) |

| Have partner but no-cohabiting | 5967 (5.2) | 7001 (5.3) | 4499 (4.9) | 4067 (5.2) |

| No partner | 15,433 (13.4) | 17,896 (13.6) | 12,062 (13.2) | 10,427 (13.4) |

| Others | 955 (0.8) | 1161 (0.9) | 734 (0.8) | 674 (0.9) |

| Employment status | ||||

| Full-time employment | 51,516 (44.8) | 58,766 (44.8) | 40,528 (44.2) | 36,408 (46.9) |

| Retired | 10,791 (9.4) | 12,663 (9.7) | 9646 (10.5) | 7125 (9.2) |

| Housewife/husband | 7636 (6.6) | 8791 (6.7) | 6300 (6.9) | 4889 (6.3) |

| Student | 5248 (4.6) | 6297 (4.8) | 3918 (4.3) | 3782 (4.9) |

| Not employed | 6023 (5.2) | 6994 (5.3) | 4483 (4.9) | 3622 (4.7) |

| Part-time employment | 30,201 (26.3) | 33,723 (25.7) | 23,992 (26.2) | 19,546 (25.2) |

| Less than 12 h/week | 3504 (3.1) | 4014 (3.1) | 2844 (3.1) | 2273 (2.9) |

| T2D Dataset | Cancer Dataset | CRDs Dataset | CVDs Dataset | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| New cases/n | % | New cases/n | % | New cases/n | % | New cases/n | % | |

| LPs | ||||||||

| Healthy in a balanced way | 1074/45,032 | 39.2 | 2171/49,855 | 38 | 1618/37,051 | 40.4 | 1320/30,594 | 39.4 |

| Healthy but physically inactive | 393/13,537 | 11.8 | 634/14,529 | 11.1 | 523/11,067 | 12.1 | 316/8831 | 11.4 |

| Unhealthy but no substance use | 329/8991 | 7.8 | 369/11,874 | 9.1 | 369/7015 | 7.7 | 201/5938 | 7.7 |

| Unhealthy but light drinking and never smoked | 801/32,457 | 28.2 | 971/37,692 | 28.7 | 1107/25,539 | 27.9 | 658/22,455 | 28.9 |

| Unhealthy | 517/14,902 | 13 | 540/17,298 | 13.2 | 514/11,039 | 12 | 355/9827 | 12.7 |

| Healthy lifestyle scores | ||||||||

| 0 | 56/1182 | 1 | 61/1383 | 1.1 | 46/847 | 0.9 | 35/693 | 0.9 |

| 1 | 314/8061 | 7 | 305/9463 | 7.2 | 335/6176 | 6.7 | 207/5101 | 6.6 |

| 2 | 602/19,218 | 16.7 | 737/21,940 | 16.7 | 759/14,809 | 16.2 | 474/12,581 | 16.2 |

| 3 | 720/26,069 | 22.7 | 1024/29,914 | 22.8 | 954/20,634 | 22.5 | 645/17,537 | 22.6 |

| 4 | 600/24,555 | 21.4 | 1000/27,911 | 21.3 | 835/19,668 | 21.5 | 586/16,742 | 21.6 |

| 5 | 395/17,938 | 15.6 | 742/20,530 | 15.6 | 637/14,793 | 16.1 | 448/12,376 | 15.9 |

| 6 | 253/10,528 | 9.2 | 483/11,893 | 9.1 | 356/8627 | 9.4 | 296/7421 | 9.6 |

| 7 | 117/5031 | 4.4 | 237/5657 | 4.3 | 156/4172 | 4.6 | 111/3563 | 4.6 |

| 8 | 45/1814 | 1.6 | 71/1989 | 1.5 | 44/1527 | 1.7 | 38/1240 | 1.6 |

| 9 | 12/454 | 0.4 | 21/500 | 0.4 | <10/395 | 0.4 | <10/341 | 0.4 |

| 10 | <10/69 | <0.1 | <10/68 | 0.05 | <10/63 | <0.1 | <10/50 | <0.1 |

| Unhealthy lifestyle scores | ||||||||

| 0 | 170/9337 | 8.1 | 434/10,216 | 7.8 | 272/7982 | 8.7 | 262/6803 | 8.8 |

| 1 | 533/21,853 | 19 | 1054/24,409 | 18.6 | 717/18,347 | 20 | 571/15,388 | 19.8 |

| 2 | 662/27,424 | 23.9 | 1190/31,111 | 23.7 | 949/22,218 | 24.2 | 724/18,602 | 24 |

| 3 | 640/23,522 | 20.5 | 954/26,958 | 20.5 | 894/18,645 | 20.3 | 560/15,743 | 20.3 |

| 4 | 517/16,551 | 14.4 | 552/19,421 | 14.8 | 673/12,756 | 13.9 | 377/11,006 | 14.2 |

| 5 | 293/9339 | 8.1 | 298/11,075 | 8.4 | 362/6967 | 7.6 | 204/5948 | 7.7 |

| 6 | 193/4563 | 4 | 131/5317 | 4.1 | 176/3249 | 3.5 | 102/2803 | 3.6 |

| 7 | 77/1717 | 1.5 | 53/2018 | 1.5 | 74/1154 | 1.3 | 33/1007 | 1.3 |

| 8 | 24/506 | 0.4 | 15/592 | 0.5 | 13/318 | 0.4 | 14/282 | 0.4 |

| 9 | <10/102 | <0.1 | <10/123 | <0.1 | <10/69 | <0.1 | <10/60 | <0.1 |

| 10 | <5/5 | <0.1 | <8/8 | <0.1 | <6/6 | <0.1 | <3/3 | <0.1 |

| T2D Incidence | Cancer Incidence | CRDs Incidence | CVDs Incidence | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LPs | ||||

| Unhealthy | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) |

| Healthy in a balanced way | 0.54 (0.49–0.60) | 0.87 (0.79–0.96) | 0.79 (0.71–0.88) | 0.91 (0.81–1.03) |

| Healthy but physically inactive | 0.60 (0.52–0.69) | 0.82 (0.73–0.93) | 0.68 (0.60–0.77) | 0.82 (0.70–0.96) |

| Unhealthy but no substance use | 1.27 (1.11–1.47) | 0.85 (0.74–0.97) | 1.01 (0.88–1.16) | 1.16 (0.97–1.38) |

| Unhealthy but light drinking and never smoked | 0.89 (0.79–0.99) | 0.91 (0.82–1.02) | 0.95 (0.86–1.06) | 1.05 (0.92–1.20) |

| Degree of Freedom | Log-Likelihood | χ2 | df | p Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Healthy lifestyle scores | ||||||

| T2D | Linear model | 1 | −32,499.32 | 6.40 | 1 | 0.011 * |

| Optimal non-linear model | 2 | −32,496.12 | ||||

| Cancer | Linear model | 1 | −49,359.52 | 0 | 1 | 0.948 |

| Optimal non-linear model | 2 | −49,359.52 | ||||

| CRDs | Linear model | 1 | −44,094.37 | 7.48 | 3 | 0.058 |

| Optimal non-linear model | 4 | −44,090.63 | ||||

| CVDs | Linear model | 1 | −28,666.56 | 4.51 | 3 | 0.211 |

| Optimal non-linear model | 4 | −28,664.30 | ||||

| Unhealthy lifestyle scores | ||||||

| T2D | Linear model | 1 | −32,456.71 | 4.66 | 3 | 0.198 |

| Optimal non-linear model | 4 | −32,454.38 | ||||

| Cancer | Linear model | 1 | −49,372.54 | 2.44 | 2 | 0.295 |

| Optimal non-linear model | 3 | −49,371.32 | ||||

| CRDs | Linear model | 1 | −44,095.22 | 7.48 | 2 | 0.006 ** |

| Optimal non-linear model | 3 | −44,090.06 | ||||

| CVDs | Linear model | 1 | −28,665.18 | 0.63 | 1 | 0.428 |

| Optimal non-linear model | 2 | −28,664.86 | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zou, Q.; Ogaz-González, R.; Lunter, G.; Corpeleijn, E. Lifestyle Patterns and Incidence of Cardiovascular Diseases, Cancer, Respiratory Diseases, and Type 2 Diabetes: A Large-Scale Prospective Cohort Study. Nutrients 2025, 17, 3883. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17243883

Zou Q, Ogaz-González R, Lunter G, Corpeleijn E. Lifestyle Patterns and Incidence of Cardiovascular Diseases, Cancer, Respiratory Diseases, and Type 2 Diabetes: A Large-Scale Prospective Cohort Study. Nutrients. 2025; 17(24):3883. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17243883

Chicago/Turabian StyleZou, Qian, Rafael Ogaz-González, Gerton Lunter, and Eva Corpeleijn. 2025. "Lifestyle Patterns and Incidence of Cardiovascular Diseases, Cancer, Respiratory Diseases, and Type 2 Diabetes: A Large-Scale Prospective Cohort Study" Nutrients 17, no. 24: 3883. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17243883

APA StyleZou, Q., Ogaz-González, R., Lunter, G., & Corpeleijn, E. (2025). Lifestyle Patterns and Incidence of Cardiovascular Diseases, Cancer, Respiratory Diseases, and Type 2 Diabetes: A Large-Scale Prospective Cohort Study. Nutrients, 17(24), 3883. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17243883