Yerba Mate (Ilex paraguariensis) and Rheumatoid Arthritis: A Systematic Review of Mechanistic and Clinical Evidence

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Search Strategy and Information Sources

2.2. Inclusion Criteria

2.3. Exclusion Criteria

2.4. Grouping for Synthesis

2.5. Study Selection

2.6. Data Extraction and Quality Assessment

3. Results

3.1. Human Clinical Trials and Human-Based In Vitro Studies with Yerba Mate Infusions or Non-Fractionated Extracts

3.2. Human-Based Studies with Isolated or Chemically Defined Bioactive Compounds

3.3. Animal Studies

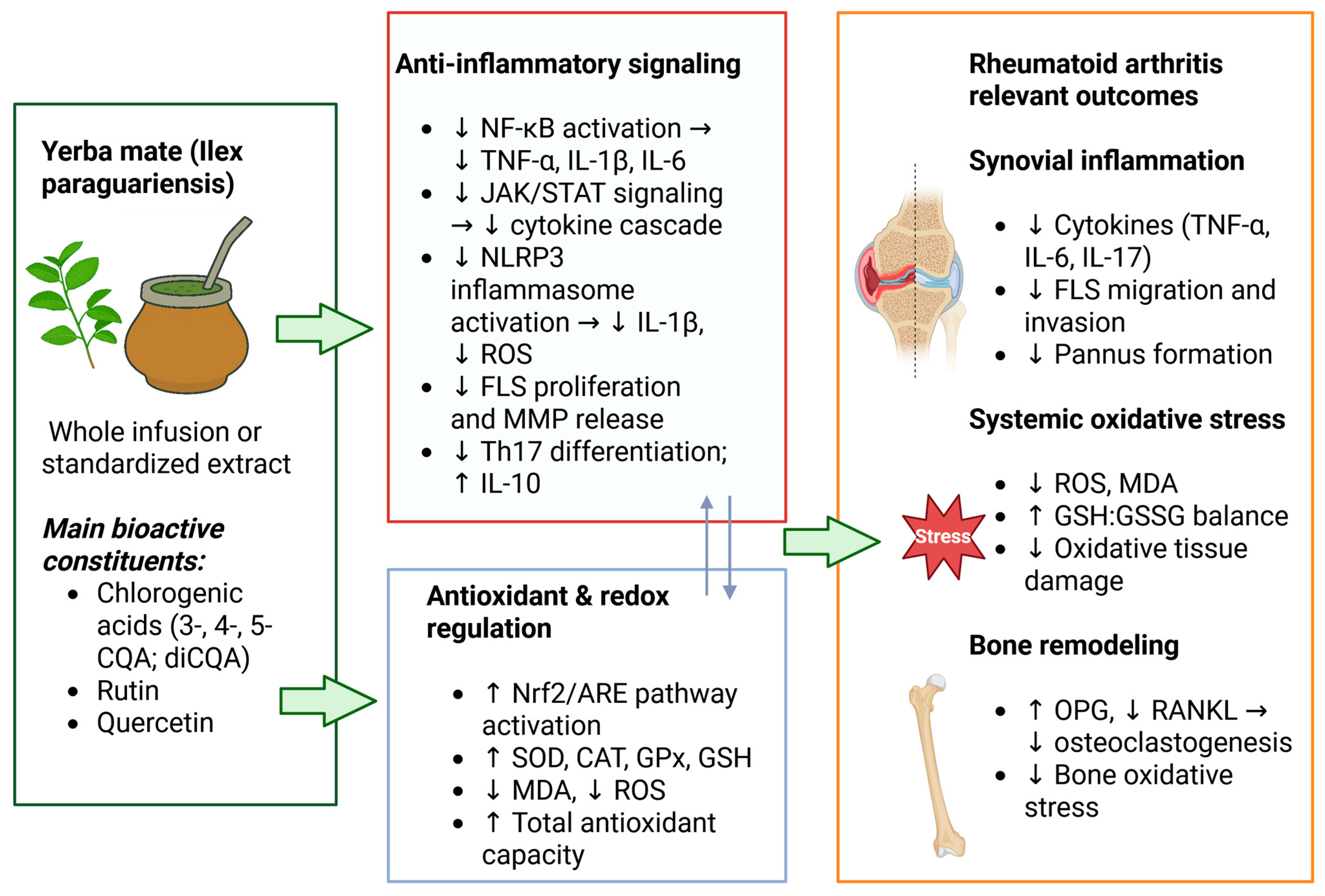

4. Discussion

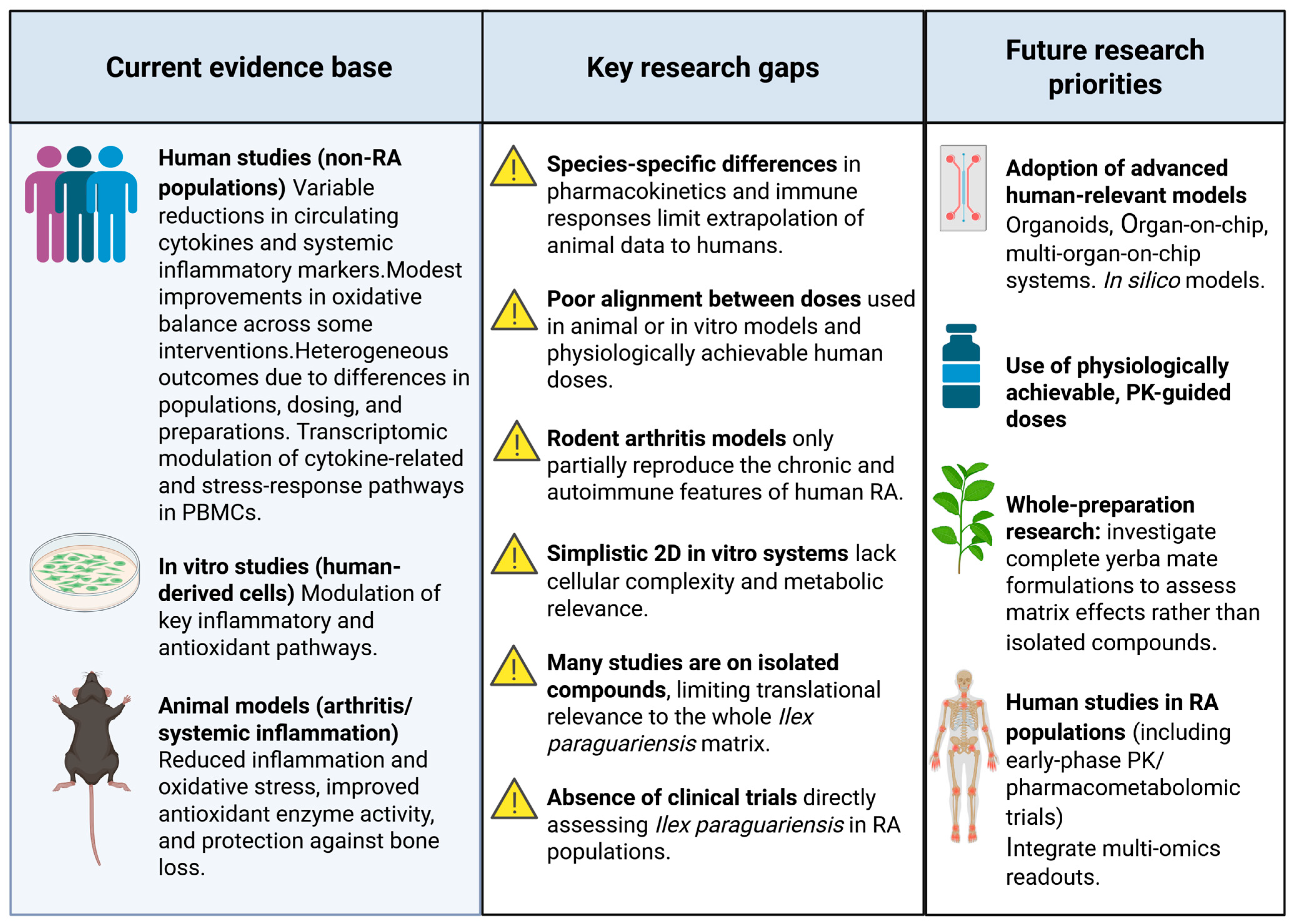

4.1. Critical Appraisal of Preclinical Evidence: Species Differences, Limitations of Traditional In Vitro Models, and Supraphysiological Concentrations

4.2. Future Perspectives and Research Directions

4.3. Limitations of the Present Review

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ADA | Adenosine Deaminase |

| ACR | American College of Rheumatology |

| ALP | Alkaline Phosphatase |

| aBMD | areal Bone Mineral Density |

| ARF | Aqueous Residual Fraction |

| BF | Butanolic Fraction |

| BMD | Bone Mineral Density |

| Caf | Caffeine |

| CAT | Catalase |

| CE | Crude Extract |

| CGA | Chlorogenic Acid |

| CRP | C-Reactive Protein |

| CQA | Caffeoylquinic Acid |

| CV | Cell Viability |

| DAS28 | Disease Activity Score in 28 joints |

| DEGs | Differentially Expressed Genes |

| DEPs | Differentially Expressed Proteins |

| DHCA | Dihydrocaffeic Acid |

| DHFA | Dihydroferulic Acid |

| diCQA | Dicaffeoylquinic Acid |

| DSS | Dextran Sodium Sulfate |

| DXA | Dual-energy X-ray Absorptiometry |

| eNOS | Endothelial Nitric Oxide Synthase |

| ESR | Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate |

| FLS | Fibroblast-like Synoviocyte |

| GATA6 | GATA-binding Protein 6 |

| GPx | Glutathione Peroxidase |

| GR | Glutathione Reductase |

| GSH | Reduced Glutathione |

| GSSG | Oxidized Glutathione |

| hUCMSCs | Human Umbilical Cord Mesenchymal Stem Cells |

| IDO | Indoleamine 2,3-Dioxygenase |

| IFN-γ | Interferon-gamma |

| IL | Interleukin |

| IL-6 | Interleukin-6 |

| JAK/STAT | Janus Kinase/Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription |

| LDH | Lactate Dehydrogenase |

| MDA | Malondialdehyde |

| MMP | Matrix Metalloproteinase |

| MPO | Myeloperoxidase |

| NF-κB | Nuclear Factor Kappa-light-chain-enhancer of Activated B Cells |

| NLRP3 | Nucleotide-binding Domain, Leucine-rich Repeat-containing Family, Pyrin Domain-containing 3 |

| NO | Nitric Oxide |

| NOx | Nitric Oxide Species |

| NPSH | Non-Protein Thiols |

| OPG | Osteoprotegerin |

| p-AKT | Phosphorylated Protein Kinase B |

| PBMCs | Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells |

| p-IκB | Phosphorylated Inhibitor of Kappa B |

| PSMB8 | Proteasome Subunit Beta 8 |

| RANKL | Receptor Activator of Nuclear Factor κB Ligand |

| RA-FLSs | Rheumatoid Arthritis Fibroblast-like Synoviocytes |

| ROS | Reactive Oxygen Species |

| Rut | Rutin |

| sBMD | Surface Bone Mineral Density (cortical) |

| SOD | Superoxide Dismutase |

| SOD2 | Superoxide Dismutase 2 |

| TAC | Total Antioxidant Capacity |

| TBARS | Thiobarbituric Acid Reactive Substances |

| Th | T Helper |

| Th17 | T Helper 17 Cells |

| TLR-3 | Toll-Like Receptor 3 |

| TNF-α | Tumor Necrosis Factor-alpha |

| t-BHP | tert-Butyl Hydroperoxide |

| TRAP | Tartrate-Resistant Acid Phosphatase |

| vBMD | Volumetric Bone Mineral Density (trabecular) |

| XIST | X-inactive Specific Transcript (long non-coding RNA) |

| YME | Yerba Mate Aqueous Extract |

| YMPE | Yerba Mate Phenolic Extract |

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. Search Strings for Pubmed

Appendix A.2. Search Strings for SciELO

Appendix A.3. Search Strings for LILACS

References

- Chauhan, K.; Jandu, J.S.; Brent, L.H.; Al-Dhahir, M.A. Rheumatoid Arthritis. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, X. Rheumatoid Arthritis: Pathogenesis and Therapeutic Advances. MedComm 2024, 5, e509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conigliaro, P.; D’Antonio, A.; D’Erme, L.; Lavinia Fonti, G.; Triggianese, P.; Bergamini, A.; Chimenti, M.S. Failure and Multiple Failure for Disease Modifying Antirheumatic Drugs in Rheumatoid Arthritis: Real-Life Evidence from a Tertiary Referral Center in Italy. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0281213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franzen, F.d.L.; Boscariol Rasera, G.; e Silva, K.F.C.; de Castro, R.J.S.; de Oliveira, M.S.R.; Bolini, H.M.A. Physicochemical Characterization and Antioxidant Potential of Plant Extracts for Use in Foods. Braz. J. Food Technol. 2025, 28, e2024085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerber, T.; Nunes, A.; Moreira, B.R.; Maraschin, M. Yerba Mate (Ilex paraguariensis A. St.-Hil.) for New Therapeutic and Nutraceutical Interventions: A Review of Patents Issued in the Last 20 Years (2000–2020). Phytother. Res. 2023, 37, 527–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brousse, M.M.; Monaca, A.B.; López, G.G.; Cruz, N.E.; Vergara, M.L.; Brousse, M.M.; Monaca, A.B.; López, G.G.; Cruz, N.E.; Vergara, M.L. Successive Concentrations of Phenolic Compounds of ‘Yerba Mate’ (Ilex paraguariensis) and Their Contribution to Antioxidant Capacity. Rev. Cienc. Tecnol. 2024, 42, 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, Z.; Xiang, W.; He, Q.; Xiao, W.; Wei, H.; Li, H.; Guo, H.; Chen, Y.; Yuan, M.; Yuan, X.; et al. Efficacy and Safety of Dietary Polyphenols in Rheumatoid Arthritis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of 47 Randomized Controlled Trials. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1024120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dojs, A.; Roś, B.; Siekaniec, K.; Kuchenbeker, N.; Mierzwińska-Mucha, J.; Jakubowicz, M. The Role of Dietary Polyphenols in Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis–A Review of Literature. J. Educ. Health Sport 2025, 82, 60290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christman, L.M.; Gu, L. Efficacy and Mechanisms of Dietary Polyphenols in Mitigating Rheumatoid Arthritis. J. Funct. Foods 2020, 71, 104003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleem, U.; Farrukh, M.; Saadullah, M.; Siddique, R.; Gul, H.; Ahmad, A.; Shaukat, B.; Shah, M.A. Role of Polyphenolics in the Management of Rheumatoid Arthritis through Intracellular Signaling Pathways: A Mechanistic Review. Inflammopharmacology 2025, 33, 2263–2275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sterne, J.A.C.; Savović, J.; Page, M.J.; Elbers, R.G.; Blencowe, N.S.; Boutron, I.; Cates, C.J.; Cheng, H.-Y.; Corbett, M.S.; Eldridge, S.M.; et al. RoB 2: A Revised Tool for Assessing Risk of Bias in Randomised Trials. BMJ 2019, 366, l4898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sterne, J.A.; Hernán, M.A.; Reeves, B.C.; Savović, J.; Berkman, N.D.; Viswanathan, M.; Henry, D.; Altman, D.G.; Ansari, M.T.; Boutron, I.; et al. ROBINS-I: A Tool for Assessing Risk of Bias in Non-Randomised Studies of Interventions. BMJ 2016, 355, i4919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooijmans, C.R.; Rovers, M.M.; de Vries, R.B.M.; Leenaars, M.; Ritskes-Hoitinga, M.; Langendam, M.W. SYRCLE’s Risk of Bias Tool for Animal Studies. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2014, 14, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gebara, K.S.; Gasparotto, A., Jr.; Palozi, R.A.C.; Morand, C.; Bonetti, C.I.; Gozzi, P.T.; de Mello, M.R.F.; Costa, T.A.; Cardozo Junior, E.L. A Randomized Crossover Intervention Study on the Effect a Standardized Maté Extract (Ilex paraguariensis A. St.-Hil.) in Men Predisposed to Cardiovascular Risk. Nutrients 2020, 13, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrilli, A.A.; Souza, S.J.; Teixeira, A.M.; Pontilho, P.M.; Souza, J.M.P.; Luzia, L.A.; Rondó, P.H.C. Effect of Chocolate and Yerba Mate Phenolic Compounds on Inflammatory and Oxidative Biomarkers in HIV/AIDS Individuals. Nutrients 2016, 8, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bravo, L.; Martínez-López, S.; Sierra-Cinos, J.L.; Mateos, R.; Sarriá, B. Yerba Mate (Ilex paraguariensis St. Hill.) Tea May Have Cardiometabolic Beneficial Effects in Healthy and At-Risk Subjects: A Randomized, Controlled, Blind, Crossover Trial in Nonhabitual Consumers. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2025, 69, e70065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panza, V.P.; Brunetta, H.S.; de Oliveira, M.V.; Nunes, E.A.; da Silva, E.L. Effect of Mate Tea (Ilex paraguariensis) on the Expression of the Leukocyte NADPH Oxidase Subunit P47phox and on Circulating Inflammatory Cytokines in Healthy Men: A Pilot Study. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2019, 70, 212–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panza, V.P.; Diefenthaeler, F.; Tamborindeguy, A.C.; Camargo, C.d.Q.; de Moura, B.M.; Brunetta, H.S.; Sakugawa, R.L.; de Oliveira, M.V.; Puel, E.d.O.; Nunes, E.A.; et al. Effects of Mate Tea Consumption on Muscle Strength and Oxidative Stress Markers after Eccentric Exercise. Br. J. Nutr. 2016, 115, 1370–1378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruskovska, T.; Morand, C.; Bonetti, C.I.; Gebara, K.S.; Cardozo Junior, E.L.; Milenkovic, D. Multigenomic Modifications in Human Circulating Immune Cells in Response to Consumption of Polyphenol-Rich Extract of Yerba Mate (Ilex paraguariensis A. St.-Hil.) Are Suggestive of Cardiometabolic Protective Effects. Br. J. Nutr. 2023, 129, 185–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazyar, H.; Moradi, L.; Zaman, F.; Zare Javid, A. The Effects of Rutin Flavonoid Supplement on Glycemic Status, Lipid Profile, Atherogenic Index of Plasma, Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor (BDNF), Some Serum Inflammatory, and Oxidative Stress Factors in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: A Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial. Phytother. Res. 2023, 37, 271–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehghani, F.; Sezavar Seyedi Jandaghi, S.H.; Janani, L.; Sarebanhassanabadi, M.; Emamat, H.; Vafa, M. Effects of Quercetin Supplementation on Inflammatory Factors and Quality of Life in Post-Myocardial Infarction Patients: A Double Blind, Placebo-Controlled, Randomized Clinical Trial. Phytother. Res. 2021, 35, 2085–2098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailly, A.R.; Hester, G.M.; Alesi, M.G.; Buresh, R.J.; Feito, Y.; Mermier, C.M.; Ducharme, J.B.; VanDusseldorp, T.A. Quercetins Efficacy on Bone and Inflammatory Markers, Body Composition, and Physical Function in Postmenopausal Women. J. Bone Miner. Metab. 2025, 43, 304–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mury, P.; Dagher, O.; Fortier, A.; Diaz, A.; Lamarche, Y.; Noly, P.-E.; Ibrahim, M.; Pagé, P.; Demers, P.; Bouchard, D.; et al. Quercetin Reduces Vascular Senescence and Inflammation in Symptomatic Male but Not Female Coronary Artery Disease Patients. Aging Cell 2025, 24, e70108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brun, L.R.; Henríquez, M.M.; Stieben, L.A.R.; Cusumano, M.; Wilches-Visbal, J.H.; Saraví, F.D.; Brance, M.L. Positive Effect of Yerba Mate (Ilex paraguariensis) Consumption on Bone Mineral Density in Postmenopausal Women Assessed by Dual Energy X-Ray Absorptiometry-Based 3-Dimensional Modeling. J. Bone Metab. 2025, 32, 123–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Chen, B.; Peng, X.; Wang, C.; Wang, K.; Han, F.; Xu, J. Quercetin Suppresses Migration and Invasion by Targeting miR-146a/GATA6 Axis in Fibroblast-like Synoviocytes of Rheumatoid Arthritis. Immunopharmacol. Immunotoxicol. 2020, 42, 221–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Ye, Y.; Cheng, M.; Tao, Y.; Zhang, K.; Huang, Q.; Deng, J.; Yao, D.; Lu, C.; Huang, Y. Quercetin Combined With Human Umbilical Cord Mesenchymal Stem Cells Regulated Tumour Necrosis Factor-α/Interferon-γ-Stimulated Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells via Activation of Toll-Like Receptor 3 Signalling. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baeza, G.; Sarriá, B.; Mateos, R.; Bravo, L. Dihydrocaffeic Acid, a Major Microbial Metabolite of Chlorogenic Acids, Shows Similar Protective Effect than a Yerba Mate Phenolic Extract against Oxidative Stress in HepG2 Cells. Food Res. Int. 2016, 87, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.-T.; Li, J.-P.; Qian, W.-Q.; Yin, M.-F.; Yin, H.; Huang, G.-C. Quercetin Suppresses Inflammatory Cytokine Production in Rheumatoid Arthritis Fibroblast-like Synoviocytes. Exp. Ther. Med. 2021, 22, 1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Yang, J.H.; Cho, S.S.; Kim, J.H.; Xu, J.; Seo, K.; Ki, S.H. 5-Caffeoylquinic Acid Ameliorates Oxidative Stress-Mediated Cell Death via Nrf2 Activation in Hepatocytes. Pharm. Biol. 2020, 58, 999–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Sarriá, B.; Mateos, R.; Goya, L.; Bravo-Clemente, L. TNF-α-Induced Oxidative Stress and Endothelial Dysfunction in EA.Hy926 Cells Is Prevented by Mate and Green Coffee Extracts, 5-Caffeoylquinic Acid and Its Microbial Metabolite, Dihydrocaffeic Acid. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2019, 70, 267–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos, J.M.D.; Touguinha, L.; Bridi, R.; Andreazza, A.C.; Bick, D.L.U.; Davidson, C.B.; dos Santos, A.F.; Machado, K.A.; Scariot, F.J.; Delamare, L.A.P.; et al. Could the Inhibition of Systemic NLRP3 Inflammasome Mediate Central Redox Effects of Yerba Mate? An in Silico and Pre-Clinical Translational Approach. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2025, 344, 119518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Carvalho, E.F.; de Oliveira, S.K.; Nardi, V.K.; Gelinski, T.C.; Bortoluzzi, M.C.; Maraschin, M.; Nardi, G.M. Ilex Paraguariensis Promotes Orofacial Pain Relief After Formalin Injection: Involvement of Noradrenergic Pathway. Pharmacogn. Res. 2016, 8, S31–S37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luz, A.B.G.; da Silva, C.H.B.; Nascimento, M.V.P.S.; de Campos Facchin, B.M.; Baratto, B.; Fröde, T.S.; Reginatto, F.H.; Dalmarco, E.M. The Anti-Inflammatory Effect of Ilex paraguariensis A. St. Hil (Mate) in a Murine Model of Pleurisy. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2016, 36, 165–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, C.S.; Stringhetta-Garcia, C.T.; da Silva Xavier, L.; Tirapeli, K.G.; Pereira, A.A.F.; Kayahara, G.M.; Tramarim, J.M.; Crivelini, M.M.; Padovani, K.S.; Leopoldino, A.M.; et al. Llex Paraguariensis Decreases Oxidative Stress in Bone and Mitigates the Damage in Rats during Perimenopause. Exp. Gerontol. 2017, 98, 148–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correa, V.G.; de Sá-Nakanishi, A.B.; Gonçalves, G.d.A.; Barros, L.; Ferreira, I.C.F.R.; Bracht, A.; Peralta, R.M. Yerba Mate Aqueous Extract Improves the Oxidative and Inflammatory States of Rats with Adjuvant-Induced Arthritis. Food Funct. 2019, 10, 5682–5696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olate-Briones, A.; Albornoz-Muñoz, S.; Rodríguez-Arriaza, F.; Rodríguez-Vergara, V.; Aguirre, J.M.; Liu, C.; Peña-Farfal, C.; Escobedo, N.; Herrada, A.A. Yerba Mate (Ilex paraguariensis) Reduces Colitis Severity by Promoting Anti-Inflammatory Macrophage Polarization. Nutrients 2024, 16, 1616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mealey, K.L.; Karriker, M.J. Comparative Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics. In Pharmacotherapeutics for Veterinary Dispensing; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2019; pp. 75–94. ISBN 978-1-119-40457-6. [Google Scholar]

- Toutain, P.-L.; Ferran, A.; Bousquet-Mélou, A. Species Differences in Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics. In Comparative and Veterinary Pharmacology; Handbook of Experimental Pharmacology; Cunningham, F., Elliott, J., Lees, P., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010; pp. 19–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correa, V.G.; Garcia-Manieri, J.A.A.; Dias, M.I.; Pereira, C.; Mandim, F.; Barros, L.; Ferreira, I.C.F.R.; Peralta, R.M.; Bracht, A. Gastrointestinal Digestion of Yerba Mate, Rosemary and Green Tea Extracts and Their Subsequent Colonic Fermentation by Human, Pig or Rat Inocula. Food Res. Int. 2024, 194, 114918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martignoni, M.; Groothuis, G.M.M.; de Kanter, R. Species Differences between Mouse, Rat, Dog, Monkey and Human CYP-Mediated Drug Metabolism, Inhibition and Induction. Expert Opin. Drug Metab. Toxicol. 2006, 2, 875–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinboth, M.; Wolffram, S.; Abraham, G.; Ungemach, F.R.; Cermak, R. Oral Bioavailability of Quercetin from Different Quercetin Glycosides in Dogs. Br. J. Nutr. 2010, 104, 198–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riva, A.; Kolimár, D.; Spittler, A.; Wisgrill, L.; Herbold, C.W.; Abrankó, L.; Berry, D. Conversion of Rutin, a Prevalent Dietary Flavonol, by the Human Gut Microbiota. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 585428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marshall, L.J.; Bailey, J.; Cassotta, M.; Herrmann, K.; Pistollato, F. Poor Translatability of Biomedical Research Using Animals-A Narrative Review. Altern. Lab. Anim. 2023, 51, 102–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, A.; Morsy, M.A.; Jacob, S. Dose Translation between Laboratory Animals and Human in Preclinical and Clinical Phases of Drug Development. Drug Dev. Res. 2018, 79, 373–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Valkengoed, D.W.; Krekels, E.H.J.; Knibbe, C.A.J. All You Need to Know About Allometric Scaling: An Integrative Review on the Theoretical Basis, Empirical Evidence, and Application in Human Pharmacology. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 2025, 64, 173–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, V.; McNeill, J.H. To Scale or Not to Scale: The Principles of Dose Extrapolation. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2009, 157, 907–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Juaristi, M.; Martínez-López, S.; Sarria, B.; Bravo, L.; Mateos, R. Absorption and Metabolism of Yerba Mate Phenolic Compounds in Humans. Food Chem. 2018, 240, 1028–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.A.; Sant, S.; Cho, S.K.; Goodman, S.B.; Bunnell, B.A.; Tuan, R.S.; Gold, M.S.; Lin, H. Synovial Joint-on-a-Chip for Modeling Arthritis: Progress, Pitfalls, and Potential. Trends Biotechnol. 2023, 41, 511–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paggi, C.A. Developing a Joint-on-Chip Platform: A Multi-Organ-on-Chip Model to Mimic Healthy and Diseased Conditions of the Synovial Joints. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Twente, Enschede, The Netherlands, 31 March 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Su, R.; Wang, H.; Wu, R.; Fan, Y.; Bin, Z.; Gao, C.; Wang, C. The Promise of Synovial Joint-on-a-Chip in Rheumatoid Arthritis. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1408501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abokor, F.A.; Al Yazeedi, S.; Baher, J.Z.; Cheung, C.; Sin, D.D.; Osei, E.T. Exploring Multi-Organ Crosstalk via the TissUse HUMIMIC Chip System: Lessons Learnt So Far. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2025, 122, 2951–2966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, S.G.; Choi, Y.Y.; Mo, S.J.; Kim, T.H.; Ha, J.H.; Hong, D.K.; Lee, H.; Park, S.D.; Shim, J.-J.; Lee, J.-L.; et al. Effect of Gut Microbiome-Derived Metabolites and Extracellular Vesicles on Hepatocyte Functions in a Gut-Liver Axis Chip. Nano Converg. 2023, 10, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tariq, M.H.; Advani, D.; Almansoori, B.M.; AlSamahi, M.E.; Aldhaheri, M.F.; Alkaabi, S.E.; Mousa, M.; Kohli, N. The Identification of Novel Therapeutic Biomarkers in Rheumatoid Arthritis: A Combined Bioinformatics and Integrated Multi-Omics Approach. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 2757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stalmach, A.; Williamson, G.; Crozier, A. Impact of Dose on the Bioavailability of Coffee Chlorogenic Acids in Humans. Food Funct. 2014, 5, 1727–1737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farah, A.; Duarte, G. Bioavailability and Metabolism of Chlorogenic Acids from Coffee. In Coffee in Health and Disease Prevention; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2015; pp. 789–801. [Google Scholar]

- Erlund, I.; Kosonen, T.; Alfthan, G.; Mäenpää, J.; Perttunen, K.; Kenraali, J.; Parantainen, J.; Aro, A. Pharmacokinetics of Quercetin from Quercetin Aglycone and Rutin in Healthy Volunteers. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2000, 56, 545–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jihwaprani, M.C.; Rizky, W.C.; Mushtaq, M.; Jihwaprani, M.C.; Rizky, W.C.; Mushtaq, M. Pharmacokinetics of Quercetin. In Quercetin-Effects on Human Health; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2023; ISBN 978-0-85466-526-6. [Google Scholar]

- Moon, Y.J.; Wang, L.; DiCenzo, R.; Morris, M.E. Quercetin Pharmacokinetics in Humans. Biopharm. Drug. Dispos. 2008, 29, 205–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almeida, A.F.; Borge, G.I.A.; Piskula, M.; Tudose, A.; Tudoreanu, L.; Valentová, K.; Williamson, G.; Santos, C.N. Bioavailability of Quercetin in Humans with a Focus on Interindividual Variation. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2018, 17, 714–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arnaud, M.J. Pharmacokinetics and Metabolism of Natural Methylxanthines in Animal and Man. In Methylxanthines; Handbook of Experimental Pharmacology; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; pp. 33–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puangpraphant, S.; de Mejia, E.G. Saponins in Yerba Mate Tea (Ilex paraguariensis A. St.-Hil) and Quercetin Synergistically Inhibit iNOS and COX-2 in Lipopolysaccharide-Induced Macrophages through NFkappaB Pathways. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2009, 57, 8873–8883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Study Design | Population/Cells | Intervention (Mate or Compound) | Outcomes Assessed | Main Findings | Risk of Bias | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled crossover trial | Adults at cardiovascular risk, 45–65 y (n = 34 men) | Encapsulated dry mate extract (580 mg caffeoylquinic acids/day, 4 weeks) | CRP, IL-6 | ↓ CRP (−50%) 0.50 ± 0.18 vs. 0.60 ± 0.25 mg/dL; p < 0.05 and ↓ IL-6 (−19%) 1.71 ± 0.26 vs. 1.39 ± 0.17 pg/mL only in higher-risk group (p < 0.05) | Some concerns (RoB 2) | [14] |

| Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover clinical trial | Adults with HIV/AIDS on ART ≥6 months, virally suppressed (n = 92) | Yerba mate 3 g/day soluble preparation vs. mate-placebo for 15 days | hs-CRP; fibrinogen; lipid profile (including HDL-c); white blood cell indices; oxidative stress (TBARS) | No significant changes in hs-CRP, fibrinogen, or TBARS vs. baseline/placebo (all p > 0.05) | High (RoB 2) | [15] |

| Randomized, controlled, single-blind, crossover trial | Adults, non-habitual yerba mate consumers, 18–55 y (n = 52 completers: 25 normocholesterolemic; 27 hypercholesterolemic) | Yerba mate tea (roasted), 3 servings/day (each 3 g sachet infused 5 min in 150 mL; ~9 g leaves/day). Estimated intake: ~666 mg/day (poly)phenols; ~66 mg/day caffeine. Control: decaffeinated, polyphenol-free isotonic drink, 3×/day. Diet: restriction of other polyphenol/methylxanthine sources. | Inflammatory cytokines (IL-1β, -2, -4, -5, -6, -7, -8, -10, -12, -13), TNF-α, IFN-γ; hsCRP; lipid peroxidation (MDA) | Broad ↓ of ILs (all p < 0.001–0.003), TNF-α ~40–50% reduction (p < 0.001), IFN-γ ~40–50% reduction (p < 0.001); hsCRP ↓ in both groups −55%; p = 0.031; MDA ↓ | High (RoB 2) | [16] |

| Pilot, two-phase crossover study (self-controlled, no placebo) | Healthy adults, men, 25 ± 3 y (n = 9) | Soluble mate tea (1 g/200 mL, 3×/day, 8 days) | Leukocyte p47phox; serum TNF-α, IL-6, IL-1β; plasma phenols; GSH, GSSG, GSH:GSSG ratio | ↓ p47phox (−22%; p = 0.030); ↓ TNF-α (−56%; p = 0.010); ↓ IL-6 (−52%; p = 0.012); ↑ plasma phenols (+30%; p = 0.004); ↑ GSH:GSSG ratio (+98%; p = 0.015); improved redox balance (↑GSH + 16.5%, p = 0.049; ↓GSSG −34%, ns). | Some concerns (RoB2) | [17] |

| Randomized crossover trial | Healthy adults, men (n = 12) | Mate tea (3 × 200 mL/day, 11 days; ~890 mg polyphenols) vs. water | Eccentric exercise; isometric strength; plasma phenolics; GSH, GSSG, GSH:GSSG ratio; LOOH | ↑ plasma phenolics (p = 0.008); Preserved GSH (mate prevented the 48–72 h decline seen in control; p = 0.002); faster strength recovery at 24 h (+8.6%; p = 0.009); no effects on GSSG, GSH:GSSG ratio, or LOOH. | High (RoB2) | [18] |

| Randomized, double-blind, crossover trial | Adults, men, 45–65 y, ≤1 metabolic syndrome criterion (n = 34) | Standardized yerba mate extract (2250 mg/day, ~581 mg CQA), 4 weeks vs. placebo | PBMC transcriptomics; inflammatory biomarkers (CRP, IL-6); NF-κB/MAPK/PI3K-Akt pathways | Modulated PBMC gene expression: 2635 DEGs (↑ 2385 protein-coding; ↓ 244 lncRNA; ↓ 6 miRNA). Subgroup: ↓ CRP (p = 0.031) and ↓ IL-6 (p < 0.001). Pathways: modulation of cytokine–cytokine receptor interaction, chemokine, MAPK, and PI3K-Akt signalling pathways. | High (RoB 2) | [19] |

| Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial | Adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus (n = 50) | Rutin supplement, 500 mg/day, 3 months | IL-6, MDA, TAC | ↓ IL-6 (−7.1 pg/mL; p = 0.002); ↓ MDA (−3.6 µM; p < 0.001); ↑ TAC (+0.16 mM; p < 0.001). | Low (RoB 2) | [20] |

| Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled parallel-group trial | Post–myocardial infarction adults, 35–65 y (n = 88) | Quercetin 500 mg/day (oral tablets, 8 weeks) | hs-CRP, IL-6, TNF-α, TAC | ↑ TAC (p < 0.001); ↓ TNF-α (within-group p = 0.009, not significant vs. placebo); no effect on hs-CRP or IL-6. | Some concerns (RoB 2) | [21] |

| Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial | Healthy post-menopausal women (n = 33) | Quercetin 500 mg/day (oral tablets, 90 days) | IL-6, TNF-α, CRP | ↓ IL-6 (p = 0.045) and ↓ TNF-α (p = 0.021) vs. placebo; no effect on CRP | Some concerns (RoB 2) | [22] |

| Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial | Adults undergoing coronary artery bypass surgery (n = 97) | Quercetin, 500 mg twice daily, 2 days pre-surgery → hospital discharge (max 7 days) | hsCRP; NO-dependent endothelial functions; SnRNA-seq; Olink 384-protein inflammation panel | ↓ hs-CRP in men (p < 0.05; group × time p = 0.025); ↓ IL-6/JAK-STAT3 and ↓ TNF-α/NF-κB pathways; ↑ NO-dependent endothelial relaxation in men (p < 0.05); DEPs in men defined by FDR < 0.05 | Some concerns (RoB 2) | [23] |

| Observational case–control study | Postmenopausal women consuming ≥1 L/day YM (n = 153) vs. non-consumers (n = 147) | Habitual yerba mate consumption | BMD (DXA), cortical/trabecular vBMD, osteoporosis diagnosis, fragility fractures | ↑ Total hip BMD (+8%; p < 0.0001); ↑ cortical & trabecular vBMD (all p < 0.0001); ↓ osteoporosis prevalence (3.3% vs. 10.9%; OR 0.276, p = 0.012); ↓ low-impact fractures (5.9% vs. 12.9%; OR 2.197, p = 0.046). | Serious (ROBINS-I) | [24] |

| In vitro mechanistic study | Human RA-FLSs | Quercetin (0, 10, 20 or 30 μM) | Cell migration and invasion, F-actin expression, miR-146a and GATA6 levels | ↑miR-146a and ↓ GATA6, leading to ↓ F-actin expression and suppression of RA-FLS migration and invasion | High (OHAT) | [25] |

| In vitro | Human PBMCs from healthy donors (TNF-α/IFN-γ–stimulated) | Quercetin (10 μM) pretreatment of hUCMSCs before coculture with activated PBMCs | PBMC proliferation; Th17 cell proportion; expression of TLR-3, p-AKT, p-IκB in hUCMSCs; secretion of IL-6, NO, and IDO | Quercetin enhanced the immunosuppressive effect of hUCMSCs → ↓PBMC proliferation; ↓ Th17 cells; ↑ TLR-3; ↓ p-AKT and ↓ p-IκB; ↑IL-6, ↑ NO, ↑ IDO | Some Concerns (OHAT) | [26] |

| In vitro | Human hepatoma HepG2 cells | YMPE, metabolites (DHCA, DHFA) | CV, LDH leakage, ROS, GSH, GPx, GR, MDA, protein carbonyls | YMPE and DHCA ↓ROS, ↓ LDH, ↓ MDA, ↓ carbonyls, ↑ GSH, normalized GPx/GR; DHFA partially effective; | Low (OHAT) | [27] |

| In vitro mechanistic study | Human RA-FLSs | Quercetin (50 nmol/L, pretreatment 2 h) | IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8; XIST, miR-485, PSMB8 expression | ↓ Inflammatory cytokines (IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8) and ↓ XIST expression in TNF-α–stimulated RA-FLSs; restored miR-485; suppressed PSMB8 upregulation; anti-inflammatory effect lost when PSMB8 silenced | High (OHAT) | [28] |

| In vitro | Human hepatocyte cell line (HepG2) | 5-Caffeoylquinic acid (5-CQA), 10–100 μM | ROS, GSH, Nrf2 nuclear translocation, ARE activity, HO-1, GCL, NQO1, Sestrin2 expression ↑ Nrf2 activation and downstream antioxidant enzymes (HO-1, GCL, NQO1, Sestrin2) | ↓ ROS production and prevention of GSH depletion under oxidative stress; protective effect abolished by Nrf2 knockout or inhibitor | High (OHAT) | [29] |

| In vitro | Human endothelial EA.hy926 cells | YMPE prepared from commercial yerba mate leaves and stems (1–50 µg/mL). | ROS, GSH, GPx, GR, protein carbonyls, eNOS levels | ↓ ROS; ↑ GSH; ↓ GPx, ↓ GR overactivation; ↓ protein carbonyls; ↑ eNOS → prevention of TNF-α–induced oxidative stress and endothelial dysfunction | High (OHAT) | [30] |

| In vitro + in silico docking | Human THP-1 macrophages | YME prepared from commercial pure leaf yerba mate (1–500 μg/mL (range), with 15 μg/mL used in efficacy experiments). | Cell viability; NO, ROS; NLRP3 inflammasome activation; gene expression; docking of chlorogenic acid and rutin to NLRP3 (MCC950 binding site) | Suppression of NLRP3 inflammasome activation in macrophages, ↓ NO and ROS, and attenuated pro-inflammatory responses; chlorogenic acid and rutin showed high predicted affinity for NLRP3 inhibition | High (OHAT) | [31] |

| Species/Model | Intervention | Dose/Duration | Outcomes Assessed | Main Findings | Risk of bias | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mice; formalin-induced orofacial nociception, writhing test, paw formalin test, carrageenan-induced paw edema | Ilex paraguariensis aqueous leaf infusion (prepared from 100 g dried leaves infused in 1 L water at 85 °C for 10 min, filtered, dried at 40 °C, and reconstituted before administration). | Oral, 1–3 g/kg, acute administration. Dose derived from habitual human mate consumption (light/moderate/heavy drinkers); no PK or formal human-equivalent dose calculation reported. | Nociception, paw edema, mechanistic pathways | ↓ Writhing; ↓ Orofacial pain (formalin test, both phases); ↔ Paw edema; ↔ Paw formalin test; effect blocked by α1-adrenoceptor antagonist → noradrenergic pathway involvement | High (SYRCLE) | [32] |

| Female Swiss mice, carrageenan-induced pleurisy | Hydroethanolic leaf extract of Ilex paraguariensis (CE) and fractions (BF, ARF), prepared by turboextraction of lyophilized leaves in 20% ethanol (1:5 m/v, 5 min); isolated compounds: Caf, Rut, CGA. | CE 10–50 mg/kg; BF and ARF 0.1–10 mg/kg; Caf 0.1–5 mg/kg; Rut 0.01–1 mg/kg; CGA 0.01–1 mg/kg; all given orally 0.5 h before pleurisy induction | Leukocyte and neutrophil migration, exudate concentration, MPO and ADA activity, NOx levels, cytokine levels (IL-6, IL-17A, IFN-γ, TNF-α, IL-10), lung histology, NF-κB p65 phosphorylation | ↓ Leukocyte and neutrophil influx; ↓ exudation, MPO, ADA, NOx; ↓ IL-6, IL-17A, IFN-γ, TNF-α; ↑ IL-10; improved lung histology; ↓ NF-κB p65 phosphorylation → overall attenuation of Th1/Th17 polarization | High (SYRCLE) | [33] |

| Female Wistar rats, “perimenopausal” (16 months); | Mate tea instant powder (commercial preparation; reconstituted in water, 0.05 g/mL; plant part not specified). | 20 mg/kg/day; Dose stated by authors as equivalent to human consumption of ~300 mL/day of mate tea and previously used in their earlier work; 4 weeks. | Areal bone mineral density (aBMD), trabecular area, osteocyte number, plasma TRAP (osteoclast activity) and ALP (osteoblast activity), bone MDA (oxidative stress marker), immunohistochemistry for RANKL, OPG, SOD2; | Increased aBMD, trabecular area, and osteocyte number; ↓ TRAP, RANKL, SOD2; ↑ OPG; ↓ bone MDA; suggesting reduced oxidative stress and inhibition of osteoclastogenesis via RANKL-dependent pathway; | High (SYRCLE) | [34] |

| Rat, adjuvant-induced arthritis | Hot-water aqueous extract of Ilex paraguariensis leaves (traditional chimarrão; 85 g leaves/1.5 L water, 5 min; lyophilized) | Oral, 400 or 800 mg/kg/day, 23 days | ROS, oxidative damage, antioxidant enzymes (SOD, CAT, GPx, GR, XO), GSH/GSSG, paw edema, leukocyte infiltration | Improved antioxidant status (↑ GSH, restored enzyme activity, ↓ ROS, ↓ damage); reduced paw swelling and inflammatory infiltration | High (SYRCLE) | [35] |

| Mouse; DSS-induced colitis model | Commercial leaf dry extract of Ilex paraguariensis, dissolved in hot water (60 °C; 1 g in 8 mL), filtered (0.2 µm) | Oral gavage, 0.025 g/mouse; 7-day pretreatment + DSS (3%) for 7 days | Inflammatory macrophage infiltration and polarization (F4/80+, CD206+, CD301+); modulation of gut inflammatory milieu | ↓ Pro-inflammatory macrophage infiltration; ↑ M2 (anti-inflammatory) macrophage polarization in colon; | High (SYRCLE) | [36] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cassotta, M.; Cao, Q.; Hu, H.; Martinez, C.R.; Dzul Lopez, L.A.; Gracia Villar, S.; Battino, M.; Giampieri, F. Yerba Mate (Ilex paraguariensis) and Rheumatoid Arthritis: A Systematic Review of Mechanistic and Clinical Evidence. Nutrients 2025, 17, 3853. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17243853

Cassotta M, Cao Q, Hu H, Martinez CR, Dzul Lopez LA, Gracia Villar S, Battino M, Giampieri F. Yerba Mate (Ilex paraguariensis) and Rheumatoid Arthritis: A Systematic Review of Mechanistic and Clinical Evidence. Nutrients. 2025; 17(24):3853. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17243853

Chicago/Turabian StyleCassotta, Manuela, Qingwei Cao, Haixia Hu, Carlos Rabeiro Martinez, Luis Alonso Dzul Lopez, Santos Gracia Villar, Maurizio Battino, and Francesca Giampieri. 2025. "Yerba Mate (Ilex paraguariensis) and Rheumatoid Arthritis: A Systematic Review of Mechanistic and Clinical Evidence" Nutrients 17, no. 24: 3853. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17243853

APA StyleCassotta, M., Cao, Q., Hu, H., Martinez, C. R., Dzul Lopez, L. A., Gracia Villar, S., Battino, M., & Giampieri, F. (2025). Yerba Mate (Ilex paraguariensis) and Rheumatoid Arthritis: A Systematic Review of Mechanistic and Clinical Evidence. Nutrients, 17(24), 3853. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17243853