Impact of Dietary Patterns on Skeletal Health: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Bone Mineral Density, Fracture, Bone Turnover Markers, and Nutritional Status

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Study Selection

2.3. Reviewing Process and Data Extraction

2.4. Risk of Bias Evaluation

2.5. Data Synthesis and Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Search Results

3.2. Characteristics of Included Studies

3.3. Quality Assessment

3.4. Effects of Different Dietary Patterns on Femoral Neck Bone Mineral Density

3.5. Effects of Different Dietary Patterns on Lumbar Spine Bone Mineral Density

3.6. Effects of Different Dietary Patterns on Total Hip Bone Mineral Density

3.7. Effects of Different Dietary Patterns on Whole-Body Bone Mineral Density

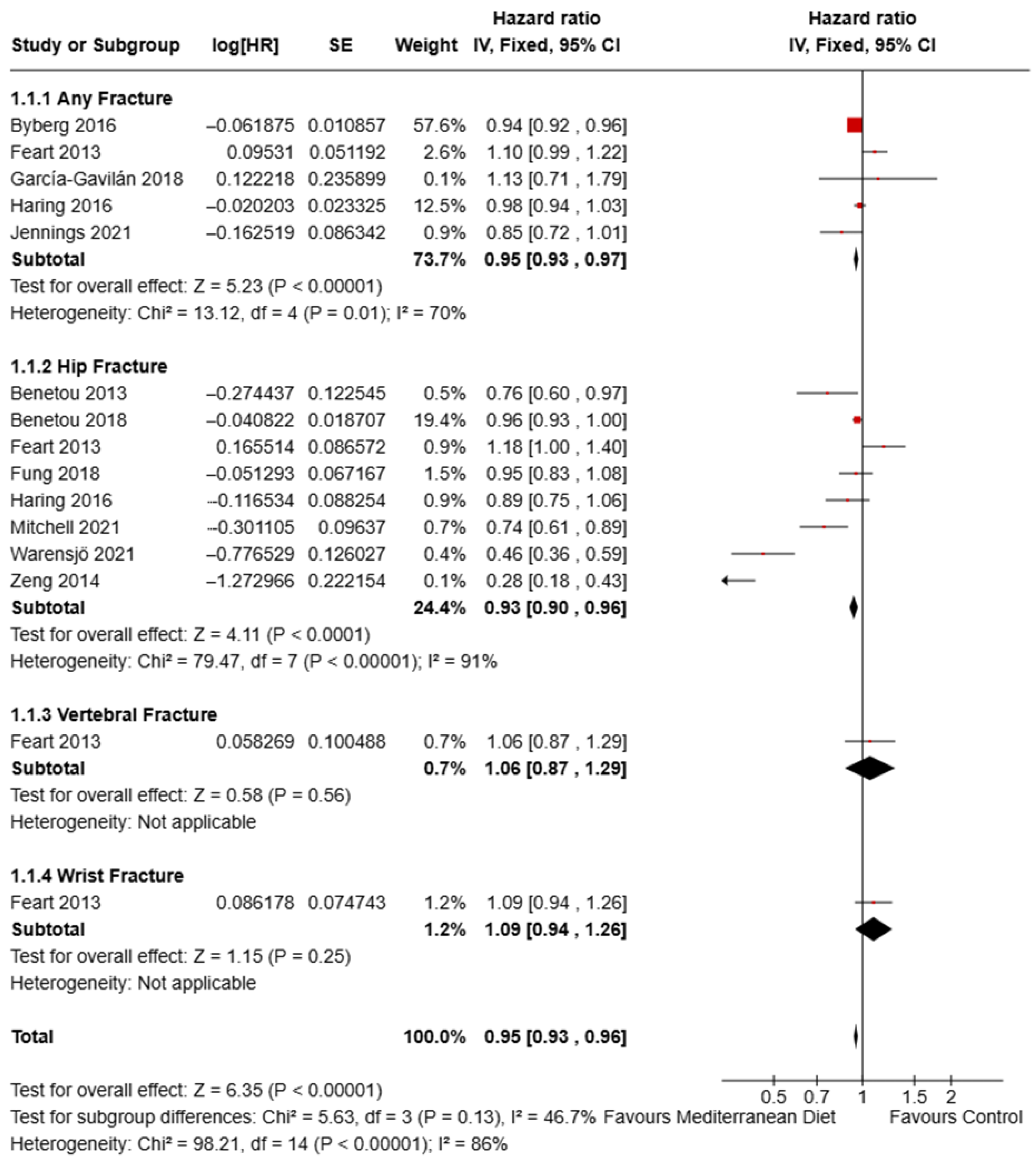

3.8. Effect of Mediterranean Diet on Fracture Risk

3.9. Effect of Different Diets on Bone Turnover Markers

3.10. Effect of Different Diets on Vitamin D and Calcium Status

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- WHO. Musculoskeletal Health. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/musculoskeletal-conditions#:~:text=Key%20facts,functional%20limitations%2C%20is%20rapidly%20increasing (accessed on 13 September 2025).

- Inoue, T.; Maeda, K.; Satake, S.; Matsui, Y.; Arai, H. Osteosarcopenia, the co-existence of osteoporosis and sarcopenia, is associated with social frailty in older adults. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 2022, 34, 535–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curtis, E.M.; Moon, R.J.; Harvey, N.C.; Cooper, C. The impact of fragility fracture and approaches to osteoporosis risk assessment worldwide. Bone 2017, 104, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NIH. National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases, Osteoporosis. Available online: https://www.niams.nih.gov/health-topics/osteoporosis (accessed on 13 September 2025).

- Ardeljan, A.D.; Hurezeanu, R. Sarcopenia. In StatPearls [Internet]; StatPearls Publishing LLC.: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Migliorini, F.; Giorgino, R.; Hildebrand, F.; Spiezia, F.; Peretti, G.M.; Alessandri-Bonetti, M.; Eschweiler, J.; Maffulli, N. Fragility Fractures: Risk Factors and Management in the Elderly. Medicina 2021, 57, 1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sözen, T.; Özışık, L.; Başaran, N. An overview and management of osteoporosis. Eur. J. Rheumatol. 2017, 4, 46–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanis, J.A.; Norton, N.; Harvey, N.C.; Jacobson, T.; Johansson, H.; Lorentzon, M.; McCloskey, E.V.; Willers, C.; Borgström, F. SCOPE 2021: A new scorecard for osteoporosis in Europe. Arch Osteoporos 2021, 16, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonough, C.M.; Harris-Hayes, M.; Kristensen, M.T.; Overgaard, J.A.; Herring, T.B.; Kenny, A.M.; Mangione, K.K. Physical Therapy Management of Older Adults With Hip Fracture. J. Orthop. Sports Phys. Ther. 2021, 51, CPG1–CPG81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Das, C.; Das, P.P.; Kambhampati, S.B.S. Sarcopenia and Osteoporosis. Indian. J. Orthop. 2023, 57, 33–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langdahl, B.L. Overview of treatment approaches to osteoporosis. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2021, 178, 1891–1906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanakis, I.; Kousidou, O.; Karamanos, N.K. In vitro and in vivo antiresorptive effects of bisphosphonates in metastatic bone disease. Vivo 2005, 19, 311–318. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mendes, M.M.; Botelho, P.B.; Ribeiro, H. Vitamin D and musculoskeletal health: Outstanding aspects to be considered in the light of current evidence. Endocr. Connect. 2022, 11, e210596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoy, D.; Geere, J.-A.; Davatchi, F.; Meggitt, B.; Barrero, L.H. A time for action: Opportunities for preventing the growing burden and disability from musculoskeletal conditions in low- and middle-income countries. Best. Pract. Res. Clin. Rheumatol. 2014, 28, 377–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moretti, A.; Snichelotto, F.; Liguori, S.; Paoletta, M.; Toro, G.; Gimigliano, F.; Iolascon, G. The challenge of pharmacotherapy for musculoskeletal pain: An overview of unmet needs. Ther. Adv. Musculoskelet. Dis. 2024, 16, 1759720X241253656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganesan, K.; Goyal, A.; Roane, D. Bisphosphonate. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing LLC.: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Okuno, F.; Ito-Masui, A.; Hane, A.; Maeyama, K.; Ikejiri, K.; Ishikura, K.; Yanagisawa, M.; Dohi, K.; Suzuki, K. Severe hypocalcemia after denosumab treatment leading to refractory ventricular tachycardia and veno-arterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation support: A case report. Int. J. Emerg. Med. 2023, 16, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuomo, A.; Parascandolo, I. Role of Nutrition in the Management of Patients with Chronic Musculoskeletal Pain. J. Pain. Res. 2024, 17, 2223–2238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, R.; Gómez Álvarez, C.B.; Rayman, M.; Lanham-New, S.; Woolf, A.; Mobasheri, A. Strategies for optimising musculoskeletal health in the 21(st) century. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2019, 20, 164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinosa-Salas, S.; Gonzalez-Arias, M. Nutrition: Micronutrient intake, imbalances, and interventions. In StatPearls [Internet]; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Gu, W.; Hao, W.; Xu, Y.; Li, K.; Zhao, Y.; Huang, Q. Associations of four important dietary pattern scores, micronutrients with sarcopenia and osteopenia in adults: Results from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Front. Nutr. 2025, 12, 1583795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, C.; Bryan, J.; Hodgson, J.; Murphy, K. Definition of the Mediterranean Diet; A Literature Review. Nutrients 2015, 7, 9139–9153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Zhong, Z.; Huang, C.; Wang, W. The effects of popular diets on bone health in the past decade: A narrative review. Front. Endocrinol. 2024, 14, 1287140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mazza, E.; Ferro, Y.; Pujia, R.; Mare, R.; Maurotti, S.; Montalcini, T.; Pujia, A. Mediterranean Diet In Healthy Aging. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2021, 25, 1076–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsigalou, C.; Konstantinidis, T.; Paraschaki, A.; Stavropoulou, E.; Voidarou, C.; Bezirtzoglou, E. Mediterranean Diet as a Tool to Combat Inflammation and Chronic Diseases. An Overview. Biomedicines 2020, 8, 201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veronese, N.; Stubbs, B.; Noale, M.; Solmi, M.; Luchini, C.; Maggi, S. Adherence to the Mediterranean diet is associated with better quality of life: Data from the Osteoarthritis Initiative123. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2016, 104, 1403–1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cervo, M.M.C.; Scott, D.; Seibel, M.J.; Cumming, R.G.; Naganathan, V.; Blyth, F.M.; Le Couteur, D.G.; Handelsman, D.J.; Ribeiro, R.V.; Waite, L.M.; et al. Adherence to Mediterranean diet and its associations with circulating cytokines, musculoskeletal health and incident falls in community-dwelling older men: The Concord Health and Ageing in Men Project. Clin. Nutr. 2021, 40, 5753–5763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jennings, A.; Cashman, K.D.; Gillings, R.; Cassidy, A.; Tang, J.; Fraser, W.; Dowling, K.G.; Hull, G.L.J.; Berendsen, A.A.M.; de Groot, L.C.P.G.M.; et al. A Mediterranean-like dietary pattern with vitamin D3 (10 µg/d) supplements reduced the rate of bone loss in older Europeans with osteoporosis at baseline: Results of a 1-y randomized controlled trial. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2018, 108, 633–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, R.; Pizato, N.; da Mata, F.; Figueiredo, A.; Ito, M.; Pereira, M.G. Mediterranean Diet and Musculoskeletal-Functional Outcomes in Community-Dwelling Older People: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2018, 22, 655–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mourad Ouzzani, H.H.; Fedorowicz, Z.; Elmagarmid, A. Rayyan—A Web and Mobile App for Systematic Reviews. Systematic Reviews 2016, 5, 210. Available online: https://www.rayyan.ai/cite/ (accessed on 17 September 2025). [CrossRef]

- Flemyng, E.; Dwan, K.; Moore, T.H.M.; Page, M.J.; Higgins, J.P.T. Risk of Bias 2 in Cochrane Reviews: A phased approach for the introduction of new methodology. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2020, 2020, ED000148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, Z. JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis; JBI: Adelaide, Australia, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Armamento-Villareal, R.; Aguirre, L.; Napoli, N.; Shah, K.; Hilton, T.; Sinacore, D.R.; Qualls, C.; Villareal, D.T. Changes in thigh muscle volume predict bone mineral density response to lifestyle therapy in frail, obese older adults. Osteoporos. Int. 2014, 25, 551–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brinkworth, G.D.; Wycherley, T.P.; Noakes, M.; Buckley, J.D.; Clifton, P.M. Long-term effects of a very-low-carbohydrate weight-loss diet and an isocaloric low-fat diet on bone health in obese adults. Nutrition 2016, 32, 1033–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carter, J.D.; Vasey, F.B.; Valeriano, J. The effect of a low-carbohydrate diet on bone turnover. Osteoporos. Int. 2006, 17, 1398–1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-Gavilán, J.F.; Bulló, M.; Canudas, S.; Martínez-González, M.A.; Estruch, R.; Giardina, S.; Fitó, M.; Corella, D.; Ros, E.; Salas-Salvadó, J. Extra virgin olive oil consumption reduces the risk of osteoporotic fractures in the PREDIMED trial. Clin. Nutr. 2018, 37, 329–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinton, P.S.; Rector, R.S.; Linden, M.A.; Warner, S.O.; Dellsperger, K.C.; Chockalingam, A.; Whaley-Connell, A.T.; Liu, Y.; Thomas, T.R. Weight-loss-associated changes in bone mineral density and bone turnover after partial weight regain with or without aerobic exercise in obese women. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2012, 66, 606–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, T.; Yao, L.; Bazzano, L. Effects of a 12-month Low-Carbohydrate Diet vs. a Low-Fat Diet on Bone Mineral Density: A Randomized Controlled Trial. FASEB J. 2016, 30, 678.12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver-Pons, C.; Sala-Vila, A.; Cofán, M.; Serra-Mir, M.; Roth, I.; Valls-Pedret, C.; Domènech, M.; Ortega, E.; Rajaram, S.; Sabaté, J.; et al. Effects of walnut consumption for 2 years on older adults’ bone health in the Walnuts and Healthy Aging (WAHA) trial. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2024, 72, 2471–2482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perissiou, M.; Borkoles, E.; Kobayashi, K.; Polman, R. The Effect of an 8 Week Prescribed Exercise and Low-Carbohydrate Diet on Cardiorespiratory Fitness, Body Composition and Cardiometabolic Risk Factors in Obese Individuals: A Randomised Controlled Trial. Nutrients 2020, 12, 482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pop, L.C.; Sukumar, D.; Tomaino, K.; Schlussel, Y.; Schneider, S.H.; Gordon, C.L.; Wang, X.; Shapses, S.A. Moderate weight loss in obese and overweight men preserves bone quality234. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2015, 101, 659–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tirosh, A.; de Souza, R.J.; Sacks, F.; Bray, G.A.; Smith, S.R.; LeBoff, M.S. Sex Differences in the Effects of Weight Loss Diets on Bone Mineral Density and Body Composition: POUNDS LOST Trial. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2015, 100, 2463–2471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vargas-Molina, S.; Carbone, L.; Romance, R.; Petro, J.L.; Schoenfeld, B.J.; Kreider, R.B.; Bonilla, D.A.; Benítez-Porres, J. Effects of a low-carbohydrate ketogenic diet on health parameters in resistance-trained women. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2021, 121, 2349–2359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vázquez-Lorente, H.; García-Gavilán, J.F.; Shyam, S.; Konieczna, J.; Martínez, J.A.; Martín-Sánchez, V.; Fitó, M.; Ruiz-Canela, M.; Paz-Graniel, I.; Curto, A.; et al. Mediterranean Diet, Physical Activity, and Bone Health in Older Adults: A Secondary Analysis of a Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Netw. Open 2025, 8, e253710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villareal, D.T.; Fontana, L.; Das, S.K.; Redman, L.; Smith, S.R.; Saltzman, E.; Bales, C.; Rochon, J.; Pieper, C.; Huang, M.; et al. Effect of Two-Year Caloric Restriction on Bone Metabolism and Bone Mineral Density in Non-Obese Younger Adults: A Randomized Clinical Trial. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2015, 31, 40–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benetou, V.; Orfanos, P.; Feskanich, D.; Michaëlsson, K.; Pettersson-Kymmer, U.; Byberg, L.; Eriksson, S.; Grodstein, F.; Wolk, A.; Jankovic, N.; et al. Mediterranean diet and hip fracture incidence among older adults: The CHANCES project. Osteoporos. Int. 2018, 29, 1591–1599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benetou, V.; Orfanos, P.; Pettersson-Kymmer, U.; Bergström, U.; Svensson, O.; Johansson, I.; Berrino, F.; Tumino, R.; Borch, K.B.; Lund, E.; et al. Mediterranean diet and incidence of hip fractures in a European cohort. Osteoporos. Int. 2013, 24, 1587–1598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byberg, L.; Bellavia, A.; Larsson, S.C.; Orsini, N.; Wolk, A.; Michaëlsson, K. Mediterranean Diet and Hip Fracture in Swedish Men and Women. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2016, 31, 2098–2105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erkkilä, A.T.; Sadeghi, H.; Isanejad, M.; Mursu, J.; Tuppurainen, M.; Kröger, H. Associations of Baltic Sea and Mediterranean dietary patterns with bone mineral density in elderly women. Public. Health Nutr. 2017, 20, 2735–2743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feart, C.; Lorrain, S.; Ginder Coupez, V.; Samieri, C.; Letenneur, L.; Paineau, D.; Barberger-Gateau, P. Adherence to a Mediterranean diet and risk of fractures in French older persons. Osteoporos. Int. 2013, 24, 3031–3041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fung, T.T.; Meyer, H.E.; Willett, W.C.; Feskanich, D. Association between Diet Quality Scores and Risk of Hip Fracture in Postmenopausal Women and Men Aged 50 Years and Older. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2018, 118, 2269–2279.e2264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haring, B.; Crandall, C.J.; Wu, C.; LeBlanc, E.S.; Shikany, J.M.; Carbone, L.; Orchard, T.; Thomas, F.; Wactawaski-Wende, J.; Li, W.; et al. Dietary Patterns and Fractures in Postmenopausal Women: Results From the Women’s Health Initiative. JAMA Intern. Med. 2016, 176, 645–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, A.; Fall, T.; Melhus, H.; Wolk, A.; Michaëlsson, K.; Byberg, L. Is the effect of Mediterranean diet on hip fracture mediated through type 2 diabetes mellitus and body mass index? Int. J. Epidemiol. 2020, 50, 234–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonio, J.; Ellerbroek, A.; Evans, C.; Silver, T.; Peacock, C.A. High protein consumption in trained women: Bad to the bone? J. Int. Soc. Sports Nutr. 2018, 15, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, G.D.; Dong, X.W.; Zhu, Y.Y.; Tian, H.Y.; He, J.; Chen, Y.M. Adherence to the Mediterranean diet is associated with a higher BMD in middle-aged and elderly Chinese. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 25662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, C.-L.; Tsai, S.-F. The impact of protein diet on bone density in people with/without chronic kidney disease: An analysis of the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey database. Clin. Nutr. 2020, 39, 3497–3503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moradi, S.; Khorrami-nezhad, L.; Ali-akbar, S.; Zare, F.; Alipour, T.; Dehghani Kari Bozorg, A.; Yekaninejad, M.S.; Maghbooli, Z.; Mirzaei, K. The associations between dietary patterns and bone health, according to the TGF-β1 T869→C polymorphism, in postmenopausal Iranian women. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 2018, 30, 563–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pérez-Rey, J.; Roncero-Martín, R.; Rico-Martín, S.; Rey-Sánchez, P.; Pedrera-Zamorano, J.D.; Pedrera-Canal, M.; López-Espuela, F.; Lavado García, J.M. Adherence to a Mediterranean Diet and Bone Mineral Density in Spanish Premenopausal Women. Nutrients 2019, 11, 555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, F.F.; Xue, W.Q.; Cao, W.T.; Wu, B.H.; Xie, H.L.; Fan, F.; Zhu, H.L.; Chen, Y.M. Diet-quality scores and risk of hip fractures in elderly urban Chinese in Guangdong, China: A case–control study. Osteoporos. Int. 2014, 25, 2131–2141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warensjö Lemming, E.; Byberg, L.; Höijer, J.; Larsson, S.C.; Wolk, A.; Michaëlsson, K. Combinations of dietary calcium intake and mediterranean-style diet on risk of hip fracture: A longitudinal cohort study of 82,000 women and men. Clin. Nutr. 2021, 40, 4161–4170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunutsor, S.K.; Laukkanen, J.A.; Whitehouse, M.R.; Blom, A.W. Adherence to a Mediterranean-style diet and incident fractures: Pooled analysis of observational evidence. Eur. J. Nutr. 2018, 57, 1687–1700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palomeras-Vilches, A.; Viñals-Mayolas, E.; Bou-Mias, C.; Jordà-Castro, M.À.; Agüero-Martínez, M.À.; Busquets-Barceló, M.; Pujol-Busquets, G.; Carrion, C.; Bosque-Prous, M.; Serra-Majem, L.; et al. Adherence to the Mediterranean Diet and Bone Fracture Risk in Middle-Aged Women: A Case Control Study. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fa-Binefa, M.; Clara, A.; Lamas, C.; Elosua, R. Mediterranean Diet and Risk of Hip Fracture: A Systematic Review and Dose-Response Meta-Analysis. Nutr. Rev. 2024, 83, 1133–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wherry, S.J.; Miller, R.M.; Jeong, S.H.; Beavers, K.M. The Ability of Exercise to Mitigate Caloric Restriction-Induced Bone Loss in Older Adults: A Structured Review of RCTs and Narrative Review of Exercise-Induced Changes in Bone Biomarkers. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garofalo, V.; Barbagallo, F.; Cannarella, R.; Calogero, A.E.; La Vignera, S.; Condorelli, R.A. Effects of the ketogenic diet on bone health: A systematic review. Front. Endocrinol. 2023, 14, 1042744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Athinarayanan, S.J.; Adams, R.N.; Hallberg, S.J.; McKenzie, A.L.; Bhanpuri, N.H.; Campbell, W.W.; Volek, J.S.; Phinney, S.D.; McCarter, J.P. Long-Term Effects of a Novel Continuous Remote Care Intervention Including Nutritional Ketosis for the Management of Type 2 Diabetes: A 2-Year Non-randomized Clinical Trial. Front. Endocrinol. 2019, 10, 450805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saadi, M.S.S.; Das, R.; Mullath Ullas, A.; Powell, D.E.; Wilson, E.; Myrtziou, I.; Rakieh, C.; Kanakis, I. Impact of Different Anti-Hyperglycaemic Treatments on Bone Turnover Markers and Bone Mineral Density in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 7988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groenendijk, I.; den Boeft, L.; van Loon, L.J.C.; de Groot, L.C.P.G.M. High Versus low Dietary Protein Intake and Bone Health in Older Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2019, 17, 1101–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zittermann, A.; Schmidt, A.; Haardt, J.; Kalotai, N.; Lehmann, A.; Egert, S.; Ellinger, S.; Kroke, A.; Lorkowski, S.; Louis, S.; et al. Protein intake and bone health: An umbrella review of systematic reviews for the evidence-based guideline of the German Nutrition Society. Osteoporos. Int. 2023, 34, 1335–1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Rosen, C.J. New Insights into Calorie Restriction Induced Bone Loss. Endocrinol. Metab. 2023, 38, 203–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsagari, A. Dietary protein intake and bone health. J. Frailty Sarcopenia Falls 2020, 5, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Parameter | Description | Search Terms Used |

|---|---|---|

| Population | Adults (>18 y), both sexes, with no restriction on baseline musculoskeletal status | osteoporosis OR bone mineral density OR fractures OR skeletal health OR musculoskeletal disorders |

| Intervention | Dietary patterns (Mediterranean diet, ketogenic diet, high-protein diet, calorie restriction, low-carb diets) | “Mediterranean diet” OR “ketogenic diet” OR “low carbohydrate diet” OR “protein-rich diet” OR “calorie restriction” OR “dietary pattern” OR “dietary intervention” |

| Comparator | Regular diet, placebo, or other dietary interventions | control OR usual care OR standard diet |

| Outcomes | Bone mineral density (femoral neck, lumbar spine, total hip), fracture incidence, falls incidence, bone turnover markers (CTX, P1NP), calcium/vitamin D status (serum 25(OH)D, calcium intake/balance), lean body mass | BMD OR bone density OR fractures OR falls OR CTX OR P1NP OR vitamin D OR calcium OR lean mass OR body composition |

| Study Design | Randomised controlled trial (RCT) or prospective cohort study | randomised OR trial OR cohort OR longitudinal study |

| First Author (Year) | Country | Study Design | N | Age (Mean ± SD/Range) in Years | Sex (% M/F) | Health Status | Diet Type/Intervention | Comparator | Duration/Follow-Up | Key Outcomes |

| Antonio et al. (2018) [55] | USA (JISSN) | Cross-sectional/intervention | 24 | Young trained adults | 0/100 | Resistance-trained women | High-protein diet | Habitual diet | 6 months | Bone markers/BMD. |

| Armamento-Villareal et al. (2014) [34] | USA | RCT/lifestyle intervention | 107 | 69 ± 4 | Mixed | Frail, obese older adults | Lifestyle therapy (weight loss + exercise) | Usual care/baseline | 52 weeks | Thigh muscle volume ↔ BMD (DXA); lean mass–BMD correlation. |

| Benetou et al. (2018) [47] | Europe (multi-country) | Prospective cohort (CHANCES) | 140,775 | Older adults | Mixed (116,176 women, 24,599 men) | Community-dwelling older adults | Mediterranean diet adherence (mMED) | Lower adherence | Variable (cohort-dependent) | Incident hip fracture ↓ with higher MD adherence. |

| Benetou et al. (2013) [48] | Europe (EPIC, 8 countries) | Prospective cohort | 188,795 | 48.6 ± 10.8 | 48,814 M/139,981 F | General population | Mediterranean diet score (10-point) | Lower adherence | 9 years | Incident hip fractures (protective association). |

| Brinkworth et al. (2016) [35] | Australia | Randomised cross-over RCT | 118 | 51.3 ± 7.1 (24–64) | Mixed | Abdominal obesity ± metabolic risk | Very-low-carbohydrate, energy-restricted diet | Isocaloric low-fat diet | 12 months | Total-body BMC/BMD (DXA); BTMs NR. |

| Byberg et al. (2016) [49] | Sweden | Prospective cohort (pooled) | 71,333 | ~60 | 53/47 | Adults free of CVD/cancer | Mediterranean diet (mMED) | Low adherence | 15 years | Incident hip fracture (n = 3175). |

| Carter et al. (2006) [36] | USA | RCT | 30 | 40.08 ± 6.0 | Mixed | Adults on low-carbohydrate diet | Low-carbohydrate diet | Control diet | 1–3 months | Bone turnover markers (uNTx, BAP); no significant difference. |

| Cervo et al. (2021) [27] | Australia (CHAMP) | Prospective cohort | 794 (x-sec); 616 (long.) | 81.1 ± 4.5 | 100 M | Older men | Mediterranean diet (MEDI-LITE) | Low adherence | 3 years | BMD ↑ with higher score; ALM and falls improved. |

| Chen et al. (2016) [56] | China | Cross-sectional | 2371 | 40–75 | Mixed | Community adults | Mediterranean diet adherence | – | 3 years | Higher adherence → higher BMD; BTMs/Vit D NR. |

| Erkkilä et al. (2017) [50] | Finland | Prospective cohort | 554 (F) | 67.9 ± 1.9 | 100 F | Elderly women | Mediterranean and Baltic Sea diets | Lower adherence | 3 years | Lumbar, femoral, and total BMD (DXA). |

| Feart et al. (2013) [51] | France | Prospective cohort | 1482 | ≥67 | Mixed | Older community dwellers | Mediterranean diet adherence | Lower adherence | 8 years | Incidence of hip, vertebral, wrist fractures. |

| Fung et al. (2018) [52] | USA | Prospective cohort (NHS and HPFS) | 111,048 | ≥50 | Mixed | Postmenopausal women and older men | High diet quality scores (AHEI, aMed, DASH, HEI) | Low diet quality scores | 26–32 years | No significant association between diet quality and hip fracture risk. |

| García-Gavilán et al. (2018) [37] | Spain (PREDIMED) | RCT | 870 (subset) | 55–80 | Mixed | High CVD risk | MedDiet + EVOO/nuts | Low-fat diet | 8.9 years | Osteoporotic fracture risk ↓ (EVOO group). |

| Haring et al. (2016) [53] | USA (WHI-OS) | Prospective cohort (post hoc) | 90,014 | 63.6 ± 7.4 (50–79) | 0/100 | Postmenopausal women | aMED, HEI-2010, AHEI-2010, DASH | Low adherence | 15.9 years | Hip and total fractures; BMD (hip/whole-body); lean mass. |

| Hinton et al. (2012) [38] | USA | RCT (weight loss) | 40 | 39 ± 1 | 100% female | Obese women | Calorie restriction diet | Partial regain ± aerobic exercise | 12 months | BMD and BTMs after weight loss/regain. |

| Hu et al. (2016) [39] | USA | RCT | 21 (9/12) | 52.7 (10.7)/51.8 (11.7) | 0/100 | Obese women (no DM, CVD, CKD) | Low-carb (<40 g day−1) | Low-fat (<30% kcal fat) | 12 months | BMD (L1–4, femur, neck T/Z-scores). |

| Jennings et al. (2018) [28] | Europe (5 countries) | RCT | 1142 | 70.9 ± 4.0 | 44/56 | Older Europeans (osteoporosis subset) | Med-like diet + Vit D3 (10 µg day−1) | Control diet | 1 years | BMD (femoral neck, lumbar, whole-body) ↑; slower bone loss. |

| Lee et al. (2020) [57] | USA (NHANES) | Cross-sectional analysis | 12,812 | 46.25 ± 0.34 | Mixed | With/without CKD | Protein intake levels | – | NR | Protein intake correlated with BMD in CKD and non-CKD groups. |

| Mitchell et al. (2020) [54] | Sweden | Prospective cohort (COSM and SMC) | 50,755 | Middle–older adults | Mixed | Healthy adults at baseline | Mediterranean diet (mMED; low–high adherence) | Low mMED adherence | 17 years | High adherence reduced hip fracture risk (OR 0.73–0.82); not mediated by BMI or T2DM. |

| Moradi et al. (2018) [58] | Iran | Cross-sectional | 254 | 57.8 ± 6.1 (46–78) | 0/100 | Postmenopausal women | Mediterranean/traditional/unhealthy diets | – | NR | BMD (L2–L4, femur); TGF-β1 gene–diet interaction. |

| Oliver-Pons et al. (2024) [40] | Spain (WAHA) | RCT (two-centre) | 352 (BMD); 211 subset | 63–79 | Mixed | Healthy older adults | Walnut-enriched diet (~15% energy) | Usual diet (no walnuts) | 2 years | BMD (spine, neck); bone biomarkers (OCN, OPG, sclerostin). |

| Pérez-Rey et al. (2019) [59] | Spain | Cross-sectional | 442 | 42.7 ± 6.7 | 0/100 | Premenopausal women | Mediterranean diet adherence | – | NR | BMD ↑ with higher MD adherence. |

| Perissiou et al. (2020) [41] | Australia | RCT (exercise + diet) | 64 (33/31) | 35.3 ± 9 | Mixed | Obese adults (BMI 30–35) | Low-carb (≤50 g day−1) + exercise | Standard diet + exercise | 8 weeks | Total BMD ↔ lean mass ↓ in LC group. |

| Pop et al. (2015) [42] | USA | RCT (weight-loss men) | 38 | 58 ± 6 | 100 M | Overweight/obese men | Moderate weight-loss intervention | – | 6 months | Bone quality preserved; BMD/BTMs reported. |

| Tirosh et al. (2015) [43] | USA (POUNDS LOST) | RCT | 424 | 51.8 ± 8.9 (30–70) | 43/57 | Overweight/obese adults | Weight-loss diets (HP, HF, HC) | Other diet arms | 24 months | BMD (spine, hip, neck); body composition reported. |

| Vargas-Molina et al. (2021) [44] | Spain | RCT | 21 (10/11) | Young adults (resistance-trained) | 0/100 | Healthy trained women | Ketogenic diet + resistance training | Non-ketogenic diet + training | 8 weeks (+3 weeks familiarisation) | BMD/BMC (DXA) slight ↑ in KD; muscle outcomes secondary. |

| Vázquez-Lorente et al. (2025) [45] | Spain (PREDIMED-Plus) | RCT (secondary analysis) | 924 (460/464) | 65.1 ± 5.0 (55–75) | 51/49 | Older adults with metabolic syndrome | Energy-reduced MedDiet + PA + behavioural support | Ad libitum MedDiet (no PA) | 3 years | Lumbar spine BMD protective (esp. women); femur no effect. |

| Villareal et al. (2015) [46] | USA | RCT (caloric restriction) | 218 | Non-obese younger adults (20–50) | Mixed | Healthy non-obese adults | Caloric restriction (~25%) | Usual diet | 2 years | Bone metabolism and BMD changes (DXA). |

| Warensjö et al. (2021) [61] | Sweden | Longitudinal cohort | 82,092 | Middle–older adults | Mixed | General population | Combined dietary calcium intake + Mediterranean-style diet (mMED) | Low Ca or low mMED adherence | 20 years | Lowest hip fracture risk with Ca ≥800 mg/day + high mMED; risk ↑ with low Ca or mMED (HR 1.50–1.54). |

| Zeng et al. (2014) [60] | China | Case–control | 1452 (726/726) | 55–80 | Mixed | Elderly urban adults (hip fracture vs. controls) | Diet-quality scores (HEI-2005, aHEI, DQI-I, aMed) | Lower diet quality | NR | Hip fracture risk ↓ (OR ≈ 0.2–0.3 highest vs. lowest quartile). |

| Study (First Author, Year) | Design/Population | Dietary Intervention/Comparator | Duration | Biomarkers Assessed | Main Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brinkworth et al., 2016 [35] | RCT, overweight adults | Very-low-carbohydrate (LC) vs. low-fat (LF) diet | 12 months | Serum β-CrossLaps | Both LC (+24%) and LF (+32%) ↑ β-CrossLaps; no significant difference between diets. |

| Carter et al., 2006 [36] | RCT, overweight adults | Low-carbohydrate diet vs. control | 3 months | uNTx, BAP, Bone turnover ratio | No significant differences in uNTx or BAP; minor non-significant changes; greater weight loss in low-carb group. |

| Villareal et al., 2015 [46] | RCT, older adults | Caloric restriction (CR) vs. ad libitum (AL) | 24 months | CTX, TRAP5b, BAP, P1NP | CR ↑ CTX and TRAP5b (6–12 mo); ↓ BAP at 12–24 mo; P1NP unchanged. |

| Armamento-Villareal et al., 2014 [34] | RCT, obese older adults | Diet, exercise, diet + exercise vs. control | 12 months | CTX, OCN, P1NP, Sclerostin, IGF-1 | Diet ↑ CTX (+31%), OCN (+24%), P1NP (+9%), Sclerostin (+10.5%); Exercise ↓ CTX (−13%), OCN (−15%), P1NP (−15%); combined intervention prevented sclerostin rise. |

| Oliver-Pons et al., 2024 [40] | RCT, adults | Walnut supplementation vs. control | 24 months | ACTH, DKK1, OPG, OCN, OPN, SOST, PTH, FGF-23 | No significant group differences; trend toward ↑ PTH (p = 0.054). |

| Cervo et al., 2021 [27] | Prospective cohort | High vs. low Mediterranean diet adherence (MEDI-LITE) | 3 years | 24 cytokines, BMD, lean mass | No significant cytokine associations after correction; weak inverse link of IL-7 with diet; no BMD associations. |

| Moradi et al., 2018 [58] | Cross-sectional | Mediterranean, traditional, unhealthy dietary patterns (by TGF-β1 genotype) | — | Lumbar spine Z-score, BMD, body composition | Mediterranean diet ↑ lumbar spine Z-score & ↓ fat measures; traditional diet in C allele carriers ↓ lumbar spine Z-score; no direct BTM data. |

| Study (First Author, Year) | Design/Population | Dietary Intervention/Comparator | Outcome | Mean (Intervention) | Mean (Control) | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jennings et al., 2018 [28] | RCT, adults | Mediterranean diet vs. control | 25(OH)D (ng/mL) | 5.2 (1.7–8.8) | 3.8 (0.7–6.9) | Slightly higher 25(OH)D in intervention group. |

| Byberg et al., 2016 [49] | Prospective cohort, adults | Mediterranean diet adherence vs. control | Vitamin D intake (mg/day) Calcium intake (mg/day) | 5.56 1298 | 5.58 1254 | No difference in dietary vitamin D intake. Marginally higher calcium intake with Mediterranean diet. |

| Hinton et al., 2012 [38] | RCT, adults | Calorie restriction vs. control | Vitamin D (ng/mL) Calcium intake (mg/day) | 6 ± 7.5 20 ± 210 | 5.5 ± 6.8 15 ± 200 | Slightly higher vitamin D in CR group. Slightly higher calcium intake in CR group. |

| Villareal et al., 2015 [46] | RCT, older adults | Calorie restriction (CR) vs. ad libitum (AL) | 25(OH)D (ng/mL) | +1.9 (0.7); 29.6 (0.6) | −0.3 (0.9); 29.3 (0.9) | Increased 25(OH)D from baseline in CR group. |

| Pop et al., 2015 [42] | Observational, adults | Dietary exposure not specified | 25(OH)D (nmol/L) | 68.0 ± 24.2 | 65.9 ± 17.8 | No difference between groups. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mullath Ullas, A.; Boamah, J.; Hussain, A.; Myrtziou, I.; Kanakis, I. Impact of Dietary Patterns on Skeletal Health: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Bone Mineral Density, Fracture, Bone Turnover Markers, and Nutritional Status. Nutrients 2025, 17, 3845. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17243845

Mullath Ullas A, Boamah J, Hussain A, Myrtziou I, Kanakis I. Impact of Dietary Patterns on Skeletal Health: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Bone Mineral Density, Fracture, Bone Turnover Markers, and Nutritional Status. Nutrients. 2025; 17(24):3845. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17243845

Chicago/Turabian StyleMullath Ullas, Adhithya, Joseph Boamah, Amir Hussain, Ioanna Myrtziou, and Ioannis Kanakis. 2025. "Impact of Dietary Patterns on Skeletal Health: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Bone Mineral Density, Fracture, Bone Turnover Markers, and Nutritional Status" Nutrients 17, no. 24: 3845. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17243845

APA StyleMullath Ullas, A., Boamah, J., Hussain, A., Myrtziou, I., & Kanakis, I. (2025). Impact of Dietary Patterns on Skeletal Health: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Bone Mineral Density, Fracture, Bone Turnover Markers, and Nutritional Status. Nutrients, 17(24), 3845. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17243845