Determinants of the Availability of Special Diet Meals in Public Schools from Kraków (Poland): A Cross-Sectional Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

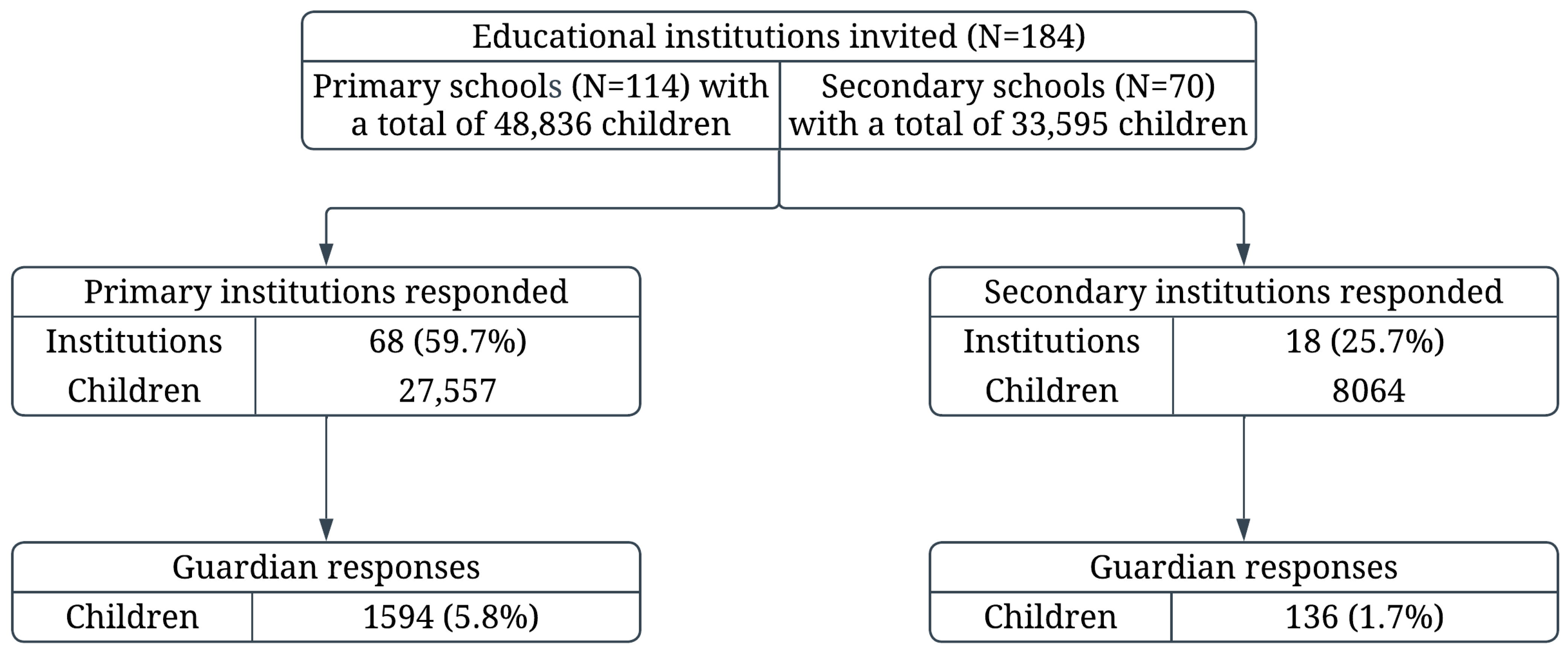

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Data Collection

2.2. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Organization of Nutrition and Availability of Special Diet Meals from the Perspective of School Managers

3.2. Organization of Nutrition and Availability of Special Diet Meals from the Perspective of Parents

4. Discussion

Strengths and Limitations of the Study

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| DINO-PL | Program Diagnoza-Interwencja-Nadciśnienie-Otyłość (in Polish) |

| COSI | Childhood Obesity Surveillance Initiative |

| HBSC | Health Behaviour in School-aged Children |

| BMI | Body Mass Index |

| IOTF | International Obesity Task Force |

| CAWI | Computer-Assisted Web Interview |

| SDs | Standard Deviations |

| IQR | Interquartile Ranges |

| ORs | Odds ratios |

| CIs | Confidence Intervals |

| CACFP | Child and Adult Care Food Program |

| EU | European Union |

| NIK | Supreme Audit Office in Poland |

References

- Cruchet, S.; Lucero, Y.; Cornejo, V. Truths, myths and needs of special diets: Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, autism, non-celiac sensitivity, and vegetarianism. Ann. Nutr. Metab. 2016, 68 (Suppl. 1), 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Implementing School Food and Nutrition Policies: A Review of Contextual Factors; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240035072 (accessed on 5 September 2025).

- Woynarowska, B. (Ed.) Students with Chronic Diseases: How to Support Their Development, Health, and Education; [Uczniowie z chorobami przewlekłymi. Jak wspierać ich rozwój, zdrowie i edukację]; PWN Publishers: Warsaw, Poland, 2010. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Pecoraro, L.; Mastrorilli, C.; Arasi, S.; Barni, S.; Caimmi, D.; Chiera, F.; Dinardo, G.; Gracci, S.; Miraglia Del Giudice, M.; Bernardini, R.; et al. Diagnostic Commission of the Italian Society of Pediatric Allergy and Immunology (SIAIP). Nutritional and Psychosocial Impact of Food Allergy in Pediatric Age. Life 2024, 14, 695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahmani, J.; Nicklaus, S.; Marty, L. Willingness for more vegetarian meals in school canteens: Associations with family characteristics and parents’ food choice motives. Appetite 2024, 193, 107134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Draft Regulation of the Minister of Health on Groups of Food Products Intended for Sale to Children and Adolescents in Educational Institutions and on the Requirements That Must be Met by Food Products used in the Collective Nutrition of Children and Adolescents in These Institutions [Projekt rozporządzenia Ministra Zdrowia w sprawie grup środków spożywczych przeznaczonych do sprzedaży dzieciom i młodzieży w jednostkach systemu oświaty oraz wymagań, jakie muszą spełniać środki spożywcze stosowane w ramach żywienia zbiorowego dzieci i młodzieży w tych jednostkach]. Available online: https://legislacja.rcl.gov.pl/projekt/12399053/katalog/13136952#13136952 (accessed on 5 September 2025).

- Fijałkowska, A.; Oblacińska, A.; Dzielska, A.; Nałęcz, H.; Korzycka, M.; Okulicz-Kozaryn, K.; Bójko, M.; Radiukiewicz, K. (Eds.) Children’s Health During the COVID-19 Pandemic; [Zdrowie dzieci w pandemii COVID-19: Raport z badań dotyczących zdrowia i zachowań zdrowotnych dzieci w wieku 8 lat podczas pandemii COVID-19]; Institute of Mother and Child: Warsaw, Poland, 2022; p. 24. Available online: https://imid.med.pl/pl/do-pobrania (accessed on 5 September 2025). (In Polish)

- Fijałkowska, A.; Dzielska, A. (Eds.) Early School-Age Children’s Health Research Report 2022–2023; [Zdrowie dzieci we wczesnym wieku szkolnym. Raport z badań 2022–2023]; Institute of Mother and Child: Warsaw, Poland, 2024; p. 23. Available online: https://drive.google.com/file/d/1lr6RoM7UdZMvhA8-DK6vAqSPaKhTU7AY/view (accessed on 5 September 2025). (In Polish)

- Mazur, J.; Dzielska, A.; Małkowska-Szkutnik, A. (Eds.) Zdrowie i Zachowania Zdrowotne Uczniów 17-Letnich na tle Zmian w Drugiej Dekadzie Życia. Wyd; Instytut Matki i Dziecka: Warszawa, Poland, 2020; pp. 18–21. Available online: https://imid.med.pl/files/imid/Do%20pobrania/Raport%20Zdrowie%20i%20zachowania%20zdrowotne%20uczniów%2017.pdf (accessed on 5 September 2025). (In Polish)

- Rakić, J.G.; Hamrik, Z.; Dzielska, A.; Felder-Puig, R.; Oja, L.; Bakalár, P.; Ciardullo, S.; Abdrakhmanova, S.; Adayeva, A.; Kelly, C.; et al. A Focus on Adolescent Physical Activity, Eating Behaviours, Weight Status and Body Image in Europe, Central Asia and Canada. Health Behaviour in School-Aged Children International Report from the 2021/2022 Survey; WHO Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2024; Volume 4, pp. 14–15. Available online: https://www.who.int/europe/publications/i/item/9789289061056 (accessed on 5 September 2025).

- Reducing Childhood Obesity in Poland by Effective Policies; WHO Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2017. Available online: https://www.who.int/europe/publications/i/item/WHO-EURO-2017-2977-42735-59610 (accessed on 5 September 2025).

- Driessen, C.E.; Cameron, A.J.; Thornton, L.E.; Lai, S.K.; Barnett, L.M. Effect of changes to the school food environment on eating behaviours and/or body weight in children: A systematic review. Obes. Rev. 2014, 15, 968–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, J.; Buoncristiano, M.; Nardone, P.; Rito, A.I.; Spinelli, A.; Hejgaard, T.; Kierkegaard, L.; Nurk, E.; Kunešová, M.; Milanović, S.M.; et al. Snapshot of European Children’s Eating Habits: Results from the Fourth Round of the WHO European Childhood Obesity Surveillance Initiative (COSI). Nutrients 2020, 12, 2481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krakow’ Education in the 2023/2024 School Year [Oświata krakowska w roku szkolnym 2023/2024]; Krakow City Hall, Department of Education: Krakow, Poland, 2024; Available online: https://www.bip.krakow.pl/?dok_id=27366 (accessed on 5 September 2025).

- Kułaga, Z.; Różdżyńska-Świątkowska, A.; Grajda, A.; Gurzkowska, B.; Wojtyło, M.; Góźdź, M.; Świąder-Leśniak, A.; Litwin, M. Percentile charts for growth and nutritional status assessment in Polish children and adolescents from birth to 18 year of age. Stand. Med. Pediatr. 2015, 12, 119–135. [Google Scholar]

- Cole, T.J.; Lobstein, T. Extended international (IOTF) body mass index cut-offs for thinness, overweight and obesity. Pediatr. Obes. 2012, 7, 284–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Elm, E.; Altman, D.G.; Egger, M.; Pocock, S.J.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Vandenbroucke, J.P. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2008, 61, 344–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyons, S.A.; Clausen, M.; Knulst, A.C.; Ballmer-Weber, B.K.; Fernandez-Rivas, M.; Barreales, L.; Bieli, C.; Dubakiene, R.; Fernandez-Perez, C.; Jedrzejczak-Czechowicz, M.; et al. Prevalence of food sensitization and food allergy in children across Europe. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 2020, 8, 2736–2746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Act of 22 November 2018 Amending the Act—Law on Education, the Act on the Education System, and Certain Other Acts (Journal of Laws from 2018, Item 2245). Available online: https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/DocDetails.xsp?id=WDU20180002245 (accessed on 5 September 2025). (In Polish)

- Servin, C.; Hellerfelt, S.; Botvid, C.; Ekström, M. Special diets are common among preschool children aged one to five years in south-East Sweden according to a population-based cross-sectional survey. Acta Paediatr. 2017, 106, 634–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Međaković, J.; Čivljak, A.; Zorčec, T.; Vučić, V.; Ristić-Medić, D.; Veselinović, A.; Čivljak, M.; Puljak, L. Pain, dietary habits and physical activity of children with developmental disabilities in Croatia, North Macedonia and Serbia: A cross-sectional study. BMC Pediatr. 2024, 24, 819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piórecka, B.; Kozioł-Kozakowska, A.; Holko, P.; Kowalska-Bobko, I.; Kawalec, P. Provision of special diets to children in public nurseries and kindergartens in Kraków (Poland). Front. Nutr. 2024, 8, 1341062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regulation No 1169/2011 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 25 October 2011 on the Provision of Food Information to Consumers. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/PL/TXT/?uri=CELEX:32011R1169 (accessed on 5 September 2025).

- Mustafa, S.S.; Russell, A.F.; Kagan, O.; Kao, L.M.; Houdek, D.V.; Smith, B.M.; Wang, J.; Gupta, R.S. Parent perspectives on school food allergy policy. BMC Pediatr. 2018, 18, 164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostecka, M.; Kostecka-Jarecka, J.; Kostecka, J.; Iłowiecka, K.; Kolasa, K.; Gutowska, G.; Sawic, M. Parental Knowledge about Allergies and Problems with an Elimination Diet in Children Aged 3 to 6 Years. Children 2022, 9, 1693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalmpourtzidou, A.; Xinias, I.; Agakidis, C.; Mavroudi, A.; Mouselimis, D.; Tsarouchas, A.; Agakidou, E.; Karagiozoglou-Lampoudi, T. Diet Quality: A Neglected Parameter in Children With Food Allergies. A Cross-Sectional Study. Front. Pediatr. 2021, 9, 658778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Profio, E.; Magenes, V.C.; Fiore, G.; Agostinelli, M.; La Mendola, A.; Acunzo, M.; Francavilla, R.; Indrio, F.; Bosetti, A.; D’Auria, E.; et al. Special Diets in Infants and Children and Impact on Gut Microbioma. Nutrients 2022, 14, 3198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wright, K.; Feeney, M.; Yerlett, N.; Meyer, R. Nutritional Management of Children with Food Allergies. Curr. Treat. Options Allergy 2022, 9, 375–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, T.A.; Lin, B.H.; Guthrie, J. School Meal Nutrition Standards Reduce Disparities. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2024, 67, 249–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hock, K.; Barquera, S.; Corvalán, C.; Goodman, S.; Sacks, G.; Vanderlee, L.; White, C.M.; White, M.; Hammond, D. Awareness of and Participation in School Food Programs in Youth from Six Countries. J. Nutr. 2022, 152 (Suppl. 1), 85S–97S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, R.E.; Sahota, P.; Christian, M.S.; Cocks, K. A qualitative study exploring pupil and school staff perceptions of school meal provision in England. Br. J. Nutr. 2015, 114, 1504–1514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korzycka, M.; Jodkowska, M.; Oblacińska, A.; Fijałkowska, A. Nutrition and physical activity environments in primary schools in Poland—COSI study. Ann. Agric. Environ. Med. 2020, 27, 605–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rousham, E.K.; Goudet, S.; Markey, O.; Griffiths, P.; Boxer, B.; Carroll, C.; Petherick, E.S.; Pradeilles, R. Unhealthy food and beverage consumption in children and risk of overweight and obesity: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Adv. Nutr. 2022, 13, 1669–1696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, R.E.; Sahota, P.; Christian, M.S. Effective implementation on primary school-based healthy lifestyle programmes: A quality study of views of school staff. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauner, C.; Lavoie, N. The costs of eating gluten-free. Appl. Econ. Lett. 2022, 31, 508–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myhrstad, M.C.; Slydahl, M.; Hellmann, M.; Garnweidner-Holme, L.; Lundin, K.E.A.; Henriksen, C.; Telle-Hansen, V.H. Nutritional quality and costs of gluten-free products: A case-control study of food products on the Norwegian marked. Food Nutr. Res. 2021, 65, 6121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, X.; Copena, D.; Pérez-Neira, D. Assessment of the diet-environment-health-cost quadrilemma in public school canteens. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2023, 25, 12543–12567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monsivais, P.; Johnson, D.B. Improving nutrition in home child care. Are food costs a barrier? Public Health Nutr. 2012, 15, 370–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haney, E.; Parnham, J.C.; Chang, K.; A Laverty, A.; von Hinke, S.; Pearson-Stuttard, J.; White, M.; Millett, C.; Vamos, E.P. Dietary quality of school meals and packed lunches. Public Health Nutr. 2023, 26, 425–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oostindjer, M.; Aschemann-Witzel, J.; Wang, Q.; Skuland, S.E.; Egelandsdal, B.; Amdam, G.V.; Schjøll, A.; Pachucki, M.C.; Rozin, P.; Stein, J. Are school meals a viable and sustainable tool to improve the healthiness and sustainability of children´s diet and food consumption? A cross-national comparative perspective. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2017, 57, 3942–3958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-Muñoz, S.; Barlińska, J.; Wojtkowska, K.; Da Quinta, N.; Baranda, A.; Alfaro, B.; Santa Cruz, E. Is it possible to improve healthy food habits in schoolchildren? A cross cultural study among Spain and Poland. Food Qual. Prefer. 2022, 99, 104534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandini, L.; Danielson, M.; Esposito, L.E.; Foley, J.T.; Fox, M.H.; Frey, G.C.; Fleming, R.K.; Krahn, G.; Must, A.; Porretta, D.L.; et al. Obesity in children with developmental and/or physical disabilities. Disabil. Health J. 2015, 8, 309–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czarniecka-Skubina, E.; Hamułka, J.; Jeruszka-Bielak, M.; Gutkowska, K. Do Food and Meal Organization Systems in Polish Primary Schools Reflect. Students’ Preferences and Healthy and Sustainable Dietary Guidelines? Foods 2023, 13, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ang, I.Y.H.; Wolf, R.L.; Koch, P.A.; Gray, H.L.; Trent, R.; Tipton, E.; Contento, I.R. School Lunch Environment Factors Impacting Fruit and Vegetable Consumption. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2019, 51, 68–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Audit Report by the Supreme Audit Office (NIK) titled “Promoting and Implementing Healthy Nutrition” [“Propagowanie i wdrażanie zdrowego odżywiania” (nr P/24/082)], Warszawa. 2025. Available online: https://www.nik.gov.pl/aktualnosci/zdrowe-odzywianie.html (accessed on 9 October 2025).

- Ross, T.D. Accurate confidence intervals for binomial proportion and Poisson rate estimation. Comput. Biol. Med. 2003, 33, 509–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bach, R.L.; Wenz, A. Studying health-related internet and mobile device use using web logs and smartphone records. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0234663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | Primary Schools (N = 68) | Secondary Schools (N = 18) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of students enrolled in the schools | Median (IQR), N | 396.0 (261.5–520.0), 68 | 467.5 (137.0–726.0), 18 | 0.648 |

| Mean (SD), N | 405.3 (214.5), 68 | 448.0 (323.5), 18 | ||

| Number of students with disabilities in the schools | Median (IQR), N | 4.0 (1.0–10.0), 67 | 2.5 (1.0–5.0), 18 | 0.256 |

| Mean (SD), N | 16.6 (35.4), 67 | 19.8 (52.2), 18 | ||

| Type of meal provision in the schools | own kitchen: n (%), N | 12 (17.6), 68 | 10 (55.6), 18 | 0.009 |

| rented kitchen: n (%), N | 26 (38.2), 68 | 2 (11.1), 18 | ||

| external catering: n (%), N | 11 (16.2), 68 | 2 (11.1), 18 | ||

| other: n (%), N | 4 (5.9), 68 | 4 (22.2), 18 | ||

| Number of students eating meals in the schools | Median (IQR), N | 152.5 (115.0–250.0), 68 | 96.0 (30.0–132.0), 13 | 0.001 |

| Mean (SD), N | 184.3 (105.4), 68 | 86.6 (67.6), 13 | ||

| Number of students receiving full or partial reimbursement for collective meals | Median (IQR), N | 8.0 (3.0–16.0), 68 | 0.5 (0.0–2.0), 18 | <0.001 |

| Mean (SD), N | 17.0 (39.6), 68 | 1.7 (2.8), 18 | ||

| Provision of special diet meals in the schools | n (%), N | 37 (54.4), 68 | 5 (27.8), 18 | 0.044 |

| Number of students receiving special diet meals in the schools | Median (IQR), N | 3.5 (2.0–7.5), 36 | 1.0 (1.0–3.0), 5 | 0.236 |

| Mean (SD), N | 5.5 (6.6), 36 | 3.2 (3.9), 5 | ||

| Daily cost of nutrition for a student on a special diet (PLN) * | Median (IQR), N | 13.0 (11.0–14.0), 29 | 10.0 (9.0–14.0), 5 | 0.432 |

| Mean (SD), N | 12.4 (2.7), 29 | 11.0 (3.4), 5 | ||

| Daily cost of nutrition for a student (PLN) * | Median (IQR), N | 13.0 (10.0–14.0), 65 | 12.8 (9.0–15.0), 14 | 0.801 |

| Mean (SD), N | 12.1 (3.2), 65 | 12.1 (3.4), 14 | ||

| Dietitian employed for the preparation of the menu | n (%), N | 22 (32.4), 68 | 4 (22.2), 18 | 0.405 |

| Menu verified for compliance with current nutritional standards (energy and nutrient requirements for the relevant age group) | n (%), N | 67 (98.5), 68 | 13 (72.2), 18 | <0.001 |

| Assessment of students’ satisfaction with meals | n (%), N | 42 (61.8), 68 | 8 (44.4), 18 | 0.185 |

| Menu access provided for students and parents | n (%), N | 68 (100.0), 68 | 12 (66.7), 18 | <0.001 |

| Canteen or dining area available for students | n (%), N | 66 (97.1), 68 | 12 (66.7), 18 | <0.001 |

| Characteristic | OR (95% CI) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Facility type | Primary schools | Reference | |

| Secondary schools | 0.51 (0.0772 to 3.31) | 0.476 | |

| Number of students with disabilities in the schools | per 1 additional child | 1.03 (1.01 to 1.05) | 0.010 |

| Number of students eating meals in the schools | per 1 additional child | 1.01 (1.0003 to 1.01) | 0.039 |

| Daily cost of nutrition for a student | per 1 PLN increase | 1.40 (1.06 to 1.84) | 0.017 |

| Dietitian employed | No | Reference | |

| Yes | 7.76 (1.95 to 30.98) | 0.004 | |

| On-site kitchen available in the schools | No | Reference | |

| Yes | 0.48 (0.14 to 1.60) | 0.234 | |

| Characteristic | Primary School Students (N = 1594) | Secondary School Students (N = 136) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female sex; n (%), N | 787 (49.4), 1594 | 56 (41.2), 136 | ||

| Age, years | mean (SD), N | 10.3 (2.3), 1565 | 15.6 (2.8), 136 | |

| median (IQR), N | 10.1 (8.3 to 12.1), 1565 | 15.6 (14.6 to 17.2), 132 | ||

| BMI category; n (%), N | Overweight | 142 (9.2), 1544 | 15 (11.5), 131 | |

| Obesity | 57 (3.7), 1544 | 8 (6.1), 131 | ||

| Normal weight | 1 070 (69.3), 1544 | 95 (72.5), 131 | ||

| Underweight | 275 (17.8), 1544 | 13 (9.9), 131 | ||

| Students’ physical activity (parent assessment); n (%), N | Low | 244 (15.3), 1591 | 49 (36.3), 135 | |

| Moderate | 804 (50.5), 1591 | 58 (43.0), 135 | ||

| High | 543 (34.1), 1591 | 28 (20.7), 135 | ||

| Place of residence; n (%), N | Village | 115 (7.2), 1594 | 48 (35.3), 136 | |

| City | 1 479 (92.8), 1594 | 88 (64.7), 136 | ||

| Number of persons in the household | mean (SD), N | 3.9 (0.9), 1587 | 4.1 (1.1), 135 | |

| median (IQR), N | 4.0 (3.0 to 4.0), 1587 | 4.0 (3.0 to 5.0), 135 | ||

| Number of underage persons in the household | mean (SD), N | 1.7 (0.9), 1582 | 1.5 (1.1), 135 | |

| median (IQR), N | 2.0 (1.0 to 2.0), 1582 | 1.0 (1.0 to 2.0), 134 | ||

| Parent with occupational activity; n (%), N | Father | 229 (14.4), 1587 | 18 (13.4), 134 | |

| Mother | 113 (7.1), 1587 | 15 (11.2), 134 | ||

| Both parents | 1 245 (78.4), 1587 | 101 (75.4), 134 | ||

| Self-assessed financial situation; n (%), N | Average | 1 056 (66.4), 1591 | 95 (70.4), 135 | |

| Above average | 417 (26.2), 1591 | 25 (18.5), 135 | ||

| Below average | 118 (7.4), 1591 | 15 (11.1), 135 | ||

| Education level (mother); n (%), N | Basic | 8 (0.5), 1590 | 1 (0.7), 135 | |

| Basic vocational | 43 (2.7), 1590 | 11 (8.2), 135 | ||

| Secondary | 291 (18.3), 1590 | 45 (33.3), 135 | ||

| Higher | 1 248 (78.5), 1590 | 78 (57.8), 135 | ||

| Education level (father); n (%), N | Basic | 32 (2.0), 1589 | 4 (3.0), 135 | |

| Basic vocational | 166 (10.4), 1589 | 28 (20.7), 135 | ||

| Secondary | 397 (25.0), 1589 | 53 (39.3), 135 | ||

| Higher | 994 (62.6), 1589 | 50 (37.0), 135 | ||

| Students using oral medication for a chronic disease; n (%), N | 247 (15.5), 1592 | 23 (17.0), 135 | ||

| Students with a disability certificate; n (%), N | 87 (5.5), 1591 | 16 (11.9), 135 | ||

| Students use collective nutrition at school; n (%), N | 1034 (64.9), 1594 | 50 (36.8), 136 | ||

| Special Diet | All (N = 1730) | Primary Schools (N = 1594) | Secondary Schools (N = 136) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall (n = 277) | Parents’ Choice (n = 123) | Physician Recommendation (n = 154) | Parents’ Choice (n = 106) | Physician Recommendation (n = 136) | Parents’ Choice (n = 17) | Physician Recommendation (n = 18) | |

| Any | 277 (16.01) | 123 (7.11) | 154 (8.9) | 106 (6.65) | 136 (8.53) | 17 (12.5) | 18 (13.24) |

| Vegetarian diet | 33 (1.91) | 33 (1.91) | 0 (0) | 28 (1.76) | 0 (0) | 5 (3.68) | 0 (0) |

| Vegan diet | 4 (0.23) | 4 (0.23) | 0 (0) | 2 (0.13) | 0 (0) | 2 (1.47) | 0 (0) |

| Gluten-free diet | 45 (2.6) | 4 (0.23) | 41 (2.37) | 3 (0.19) | 36 (2.26) | 1 (0.74) | 5 (3.68) |

| Diet due to food allergy | 55 (3.18) | 11 (0.64) | 44 (2.54) | 10 (0.63) | 40 (2.51) | 1 (0.74) | 4 (2.94) |

| Diet due to food intolerance | 64 (3.7) | 17 (0.98) | 47 (2.72) | 17 (1.07) | 46 (2.89) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.74) |

| Religious diet | 3 (0.17) | 3 (0.17) | 0 (0) | 3 (0.19) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Weight loss diet | 41 (2.37) | 22 (1.27) | 19 (1.1) | 19 (1.19) | 19 (1.19) | 3 (2.21) | 0 (0) |

| Other diet | 78 (4.51) | 42 (2.43) | 36 (2.08) | 34 (2.13) | 28 (1.76) | 8 (5.88) | 8 (5.88) |

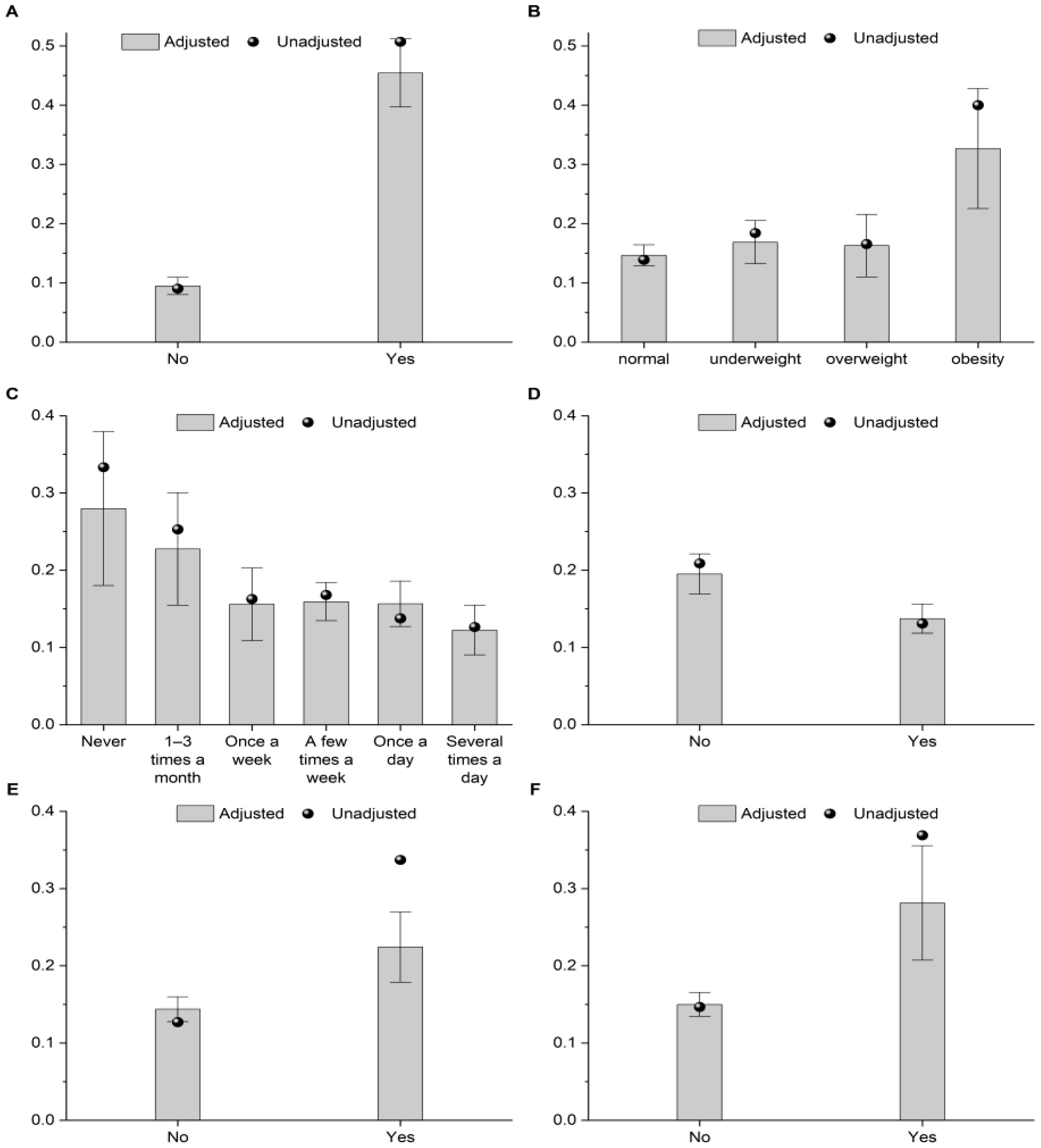

| Characteristic | OR (95% CI) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Male | Reference | |

| Female | 1.34 (0.97 to 1.85) | 0.077 | |

| Oral medication for a chronic disease | No | Reference | |

| Yes | 2.15 (1.41 to 3.26) | <0.001 | |

| Disability certificate | No | Reference | |

| Yes | 3.14 (1.77 to 5.57) | <0.001 | |

| Food intolerance or allergy | No | Reference | |

| Yes | 12.47 (8.62 to 18.04) | <0.001 | |

| BMI category | Normal | Reference | |

| Underweight | 1.26 (0.83 to 1.92) | 0.273 | |

| Overweight | 1.19 (0.66 to 2.15) | 0.561 | |

| Obesity | 4.48 (2.19 to 9.13) | <0.001 | |

| Overall effect | - | 0.001 | |

| Type of educational institution | Primary school | Reference | |

| Secondary school | 2.09 (1.07 to 4.07) | 0.030 | |

| Students attending sports classes | No | Reference | |

| Yes | 1.66 (1.04 to 2.66) | 0.035 | |

| Students snack between meals | Never | Reference | |

| 1–3 times a month | 0.67 (0.27 to 1.67) | 0.389 | |

| Once a week | 0.34 (0.14 to 0.81) | 0.015 | |

| A few times a week | 0.35 (0.16 to 0.77) | 0.009 | |

| Once a day | 0.34 (0.16 to 0.75) | 0.007 | |

| Several times a day | 0.23 (0.10 to 0.54) | 0.001 | |

| Overall effect | - | 0.011 | |

| Snack between meals: sweetened milk drinks and desserts | No | Reference | |

| Yes | 0.63 (0.42 to 0.95) | 0.027 | |

| Snack between meals: sweets | No | Reference | |

| Yes | 0.59 (0.42 to 0.83) | 0.003 | |

| Snack between meals: nuts | No | Reference | |

| Yes | 1.57 (1.10 to 2.23) | 0.012 | |

| Students buy chips in the school shop or in a nearby shop | No | Reference | |

| Yes | 1.78 (1.00 to 3.16) | 0.050 | |

| Students buy mineral water in the school shop or in a nearby store | No | Reference | |

| Yes | 1.45 (1.02 to 2.05) | 0.037 | |

| Students participate in collective nutrition at school | No | Reference | |

| Yes | 0.55 (0.39 to 0.77) | 0.001 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Piórecka, B.; Błaszczyk-Bębenek, E.; Holko, P.; Kowalska-Bobko, I.; Kawalec, P. Determinants of the Availability of Special Diet Meals in Public Schools from Kraków (Poland): A Cross-Sectional Analysis. Nutrients 2025, 17, 3834. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17243834

Piórecka B, Błaszczyk-Bębenek E, Holko P, Kowalska-Bobko I, Kawalec P. Determinants of the Availability of Special Diet Meals in Public Schools from Kraków (Poland): A Cross-Sectional Analysis. Nutrients. 2025; 17(24):3834. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17243834

Chicago/Turabian StylePiórecka, Beata, Ewa Błaszczyk-Bębenek, Przemysław Holko, Iwona Kowalska-Bobko, and Paweł Kawalec. 2025. "Determinants of the Availability of Special Diet Meals in Public Schools from Kraków (Poland): A Cross-Sectional Analysis" Nutrients 17, no. 24: 3834. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17243834

APA StylePiórecka, B., Błaszczyk-Bębenek, E., Holko, P., Kowalska-Bobko, I., & Kawalec, P. (2025). Determinants of the Availability of Special Diet Meals in Public Schools from Kraków (Poland): A Cross-Sectional Analysis. Nutrients, 17(24), 3834. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17243834