Lipid-Enriched Gintonin from Korean Red Ginseng Marc Alleviates Obesity via Oral and Central Administration in Diet-Induced Obese Mice

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Experimental Animals and Treatments

2.2.1. Animals

2.2.2. Oral Administration

2.2.3. ICV Injection

2.3. Analysis of Metabolic Rates and Energy Expenditure Profiles

2.4. Behavioral Tests

2.4.1. Exhaustive Running Test

2.4.2. Open Field Test

2.4.3. Rotarod Test

2.4.4. Forelimb Grip Strength Test

2.5. Biochemical Assays

2.6. Body Composition Analysis

2.7. Histology

2.8. Total RNA Isolation, cDNA Synthesis, and Quantitative Real-Time PCR

2.9. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Oral Administration of KRGM-Gintonin Exhibits Anti-Obesity Effects in HFD-Induced Obese Mice

3.2. Behavioral Assessments Reveal Improved Muscle Function Following Oral Administration of KRGM-Gintonin

3.3. Oral Administration of KRGM-Gintonin Enhances Energy Expenditure and Alleviates Hepatic Steatosis in HFD-Fed Mice

3.4. Alteration of Gene Related to Metabolic Parameters and Thermogenesis Signaling in BAT

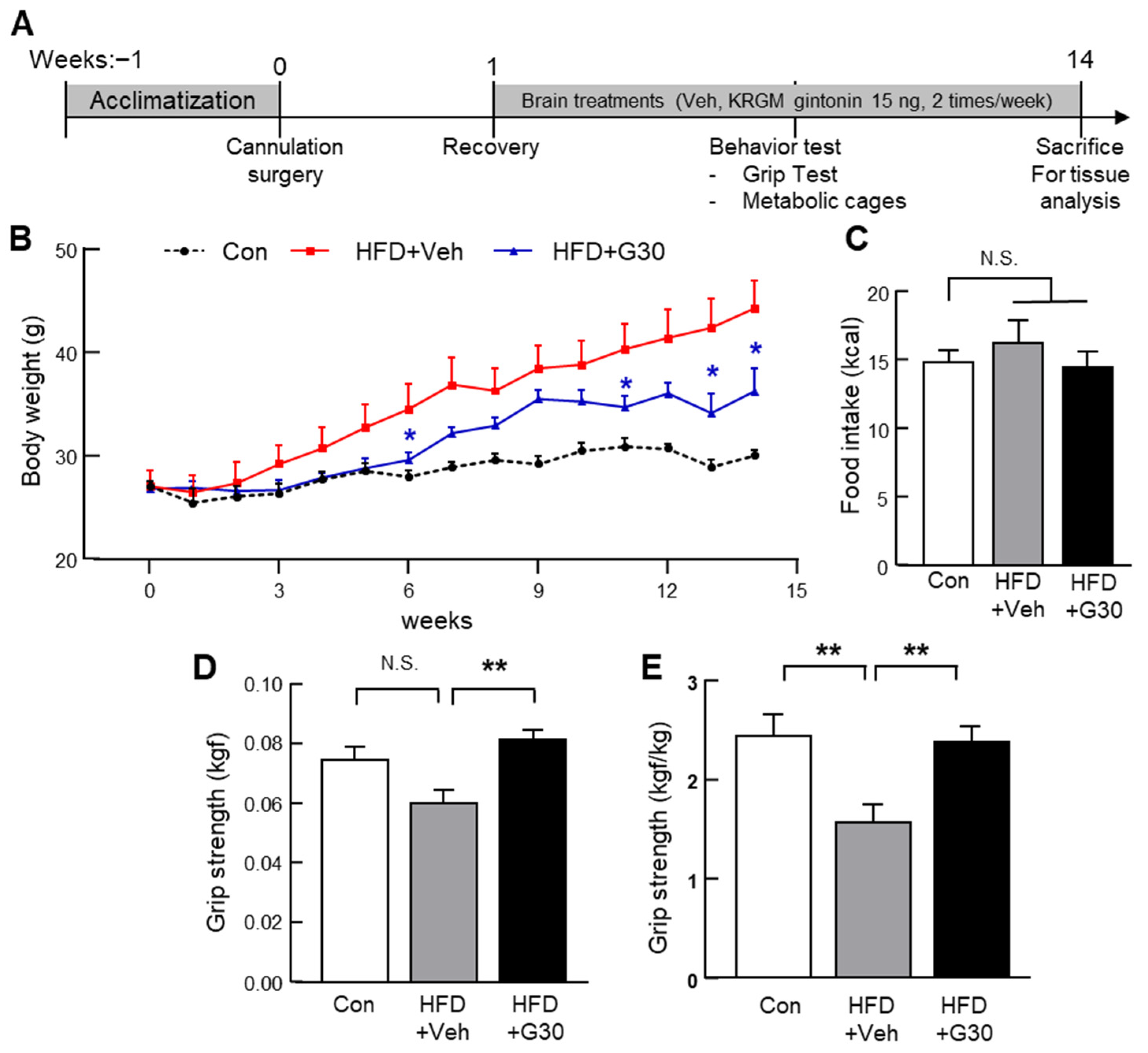

3.5. Central Administration of KRGM-Gintonin Attenuates HFD-Induced Obesity and Enhances Muscle Function

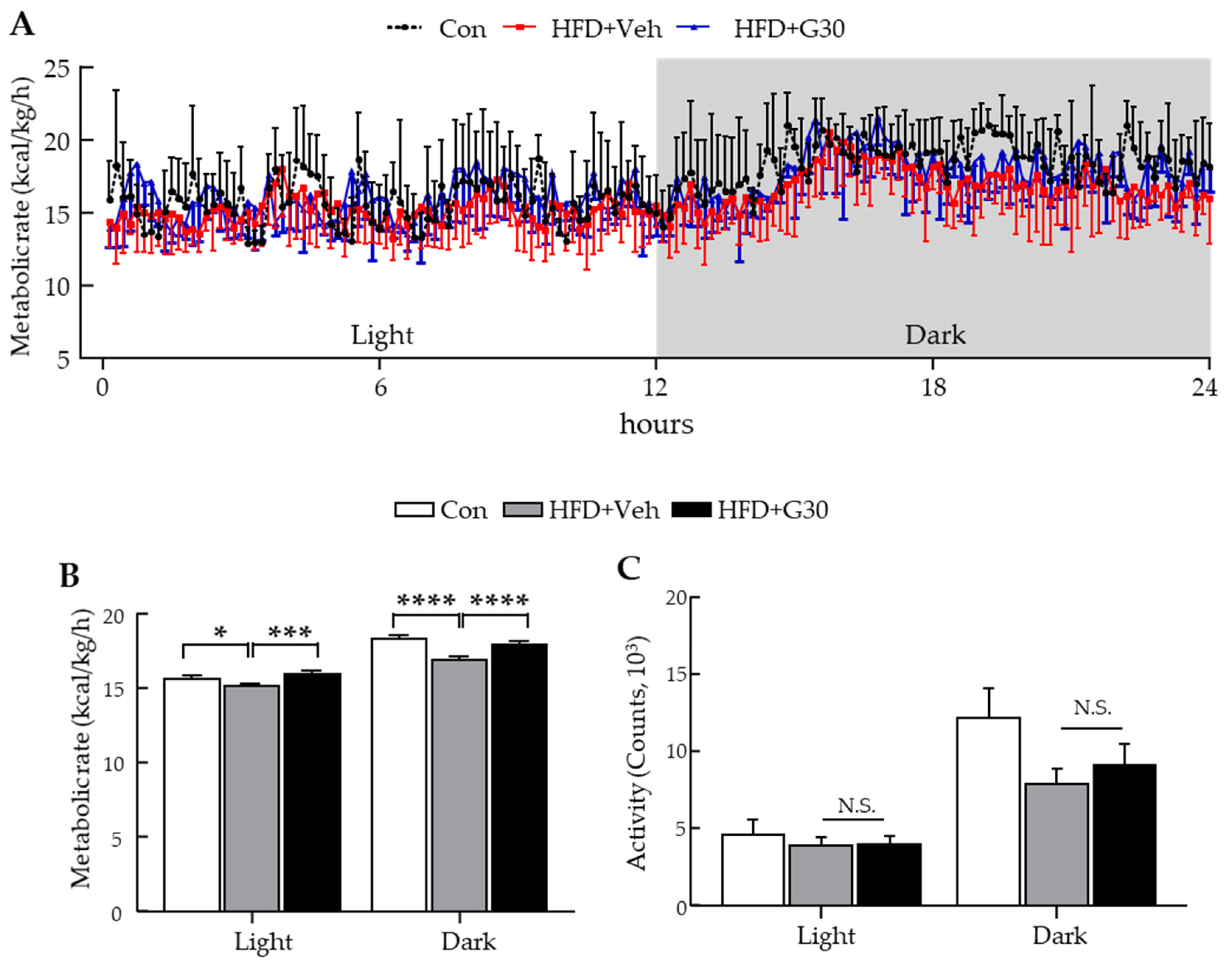

3.6. ICV Administration of KRGM-Gintonin Enhances Energy Expenditure

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ATGL | adipose triglyceride lipase |

| BAT | brown adipose tissue |

| CD | chow diet |

| FFA | free fatty acid |

| GEF | gintonin-enriched fraction |

| HFD | high-fat diet |

| HSL | hormone-sensitive lipase |

| ICV | intracerebroventricular |

| KRGM-gintonin | Korean red ginseng marc-derived gintonin |

| LPA | lysophosphatidic acid |

| LPC | lysophosphatidylcholine |

| PGC1α | Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator 1-α |

| PRDM16 | PRD1-BF1-RIZ1 homologous domain containing 16 |

| TA | tibialis anterior |

| TC | total cholesterol |

| TG | triacylglycerol |

| TNF-α | tumor necrosis factor-alpha |

| UCP1 | uncoupling protein-1 |

| WAT | white adipose tissue |

References

- Ng, M.; Fleming, T.; Robinson, M.; Thomson, B.; Graetz, N.; Margono, C.; Mullany, E.C.; Biryukov, S.; Abbafati, C.; Abera, S.F. Global, regional, and national prevalence of overweight and obesity in children and adults during 1980–2013: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet 2014, 384, 766–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aminifard, T.; Razavi, B.M.; Hosseinzadeh, H. The effects of ginseng on the metabolic syndrome: An updated review. Food Sci. Nutr. 2021, 9, 5293–5311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cinti, S. The adipose organ at a glance. Dis. Models Mech. 2012, 5, 588–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harms, M.; Seale, P. Brown and beige fat: Development, function and therapeutic potential. Nat. Med. 2013, 19, 1252–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickson, L.M.; Gandhi, S.; Layden, B.T.; Cohen, R.N.; Wicksteed, B. Protein kinase A induces UCP1 expression in specific adipose depots to increase energy expenditure and improve metabolic health. Am. J. Physiol.-Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2016, 311, R79–R88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Yang, D.; Xiang, J.; Zhou, J.; Cao, H.; Che, Q.; Bai, Y.; Guo, J.; Su, Z. Non-shivering thermogenesis signalling regulation and potential therapeutic applications of brown adipose tissue. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2021, 17, 2853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jung, S.M.; Sanchez-Gurmaches, J.; Guertin, D.A. Brown adipose tissue development and metabolism. In Handbook of Experimental Pharmacology; Pfeifer, A., Klingenspor, M., Herzig, S., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 3–36. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, D.; Lee, Y.; Kim, H.-R.; Park, Y.J.; Hwang, H.; Rhim, H.; Kang, T.; Choi, C.W.; Lee, B.; Kim, M.S. Hypothalamic administration of sargahydroquinoic acid elevates peripheral thermogenic signaling and ameliorates high fat diet-induced obesity through the sympathetic nervous system. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 21315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Townsend, K.; Tseng, Y.-H. Brown adipose tissue: Recent insights into development, metabolic function and therapeutic potential. Adipocyte 2012, 1, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, S.S.; Yoon, M. Korean red ginseng (Panax ginseng) inhibits obesity and improves lipid metabolism in high fat diet-fed castrated mice. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2018, 210, 80–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, S.J.; Kim, S.K.; Lee, N.Y.; Choi, Y.R.; Kim, H.S.; Gupta, H.; Youn, G.S.; Sung, H.; Shin, M.J.; Suk, K.T. Effect of Korean red ginseng on metabolic syndrome. J. Ginseng Res. 2021, 45, 380–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, S.H.; Shin, T.-J.; Choi, S.-H.; Cho, H.-J.; Lee, B.-H.; Pyo, M.K.; Lee, J.-H.; Kang, J.; Kim, H.-J.; Park, C.-W. Gintonin, newly identified compounds from ginseng, is novel lysophosphatidic acids-protein complexes and activates G protein-coupled lysophosphatidic acid receptors with high affinity. Mol. Cells 2012, 33, 151–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hwang, S.-H.; Lee, B.-H.; Choi, S.-H.; Kim, H.-J.; Jung, S.-W.; Kim, H.-S.; Shin, H.-C.; Park, H.J.; Park, K.H.; Lee, M.K. Gintonin, a novel ginseng-derived lysophosphatidic acid receptor ligand, stimulates neurotransmitter release. Neurosci. Lett. 2015, 584, 356–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pyo, M.-K.; Choi, S.-H.; Hwang, S.-H.; Shin, T.-J.; Lee, B.-H.; Lee, S.-M.; Lim, Y.-H.; Kim, D.-H.; Nah, S.-Y. Novel glycolipoproteins from ginseng. J. Ginseng Res. 2011, 35, 92–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, R.; Kim, J.-H.; Hwang, H.; Rhim, H.; Hwang, S.-H.; Cho, I.-H.; Kim, D.-G.; Kim, H.-C.; Nah, S.-Y. Preparation of red ginseng marc-derived gintonin and its application as a skin nutrient. Nutrients 2023, 15, 2574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, H.-J.; Choi, S.-H.; Kim, H.-J.; Lee, B.-H.; Rhim, H.; Kim, H.-C.; Hwang, S.-H.; Nah, S.-Y. Bioactive lipids in gintonin-enriched fraction from ginseng. J. Ginseng Res. 2019, 43, 209–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.G.; Lee, Y.J.; Jang, M.-H.; Kwon, T.R.; Nam, J.-O. Panax ginseng leaf extracts exert anti-obesity effects in high-fat diet-induced obese rats. Nutrients 2017, 9, 999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Li, H.; Zhao, Y.; Zhu, H.; Cai, E.; Gao, Y.; Liu, S.; Yang, H.; Zhang, L. Saponins from stems and leaves of Panax ginseng prevent obesity via regulating thermogenesis, lipogenesis and lipolysis in high-fat diet-induced obese C57BL/6 mice. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2017, 106, 393–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, Y.; Lee, R.; Jeon, S.H.; Kim, J.-H.; Jo, H.-S.; Kwon, T.W.; Hwang, S.-H.; Lee, J.K.; Nah, S.-Y.; Cho, I.-H. Korean Red Ginseng Marc-Derived Gintonin Improves Alzheimer’s Cognitive Dysfunction by Upregulating LPAR1. Am. J. Chin. Med. 2025, 53, 17–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.; Jin, H.; Chei, S.; Oh, H.-J.; Choi, S.-H.; Nah, S.-Y.; Lee, B.-Y. The gintonin-enriched fraction of ginseng regulates lipid metabolism and browning via the cAMP-protein kinase a signaling pathway in mice white adipocytes. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, H.; Oh, H.-J.; Nah, S.-Y.; Lee, B.-Y. Gintonin-enriched fraction protects against sarcopenic obesity by promoting energy expenditure and attenuating skeletal muscle atrophy in high-fat diet-fed mice. J. Ginseng Res. 2022, 46, 454–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.H.; Kwon, T.W.; Jo, H.S.; Ha, Y.; Cho, I.-H. Gintonin, a Panax ginseng-derived LPA receptor ligand, attenuates kainic acid-induced seizures and neuronal cell death in the hippocampus via anti-inflammatory and anti-oxidant activities. J. Ginseng Res. 2023, 47, 390–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.-G.; Jang, M.; Choi, S.-H.; Kim, H.-J.; Jhun, H.; Kim, H.-C.; Rhim, H.; Cho, I.-H.; Nah, S.-Y. Gintonin, a ginseng-derived exogenous lysophosphatidic acid receptor ligand, enhances blood-brain barrier permeability and brain delivery. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 114, 1325–1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Liu, J.; Ni, Y.; Yi, C.; Fang, Y.; Ning, Q.; Shen, B.; Zhang, K.; Liu, Y.; Yang, L. Global prevalence of overweight and obesity in children and adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr. 2024, 178, 800–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Ji, G.E. Ginseng and obesity. J. Ginseng Res. 2018, 42, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, H.; Dai, X.; Zhu, R.; Chen, B.; Xia, B.; Ye, Z.; Zhao, D.; Gao, S.; Orekhov, A.N. A comprehensive review on the phytochemistry, pharmacokinetics, and antidiabetic effect of Ginseng. Phytomedicine 2021, 92, 153717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pu, J.; Akter, R.; Rupa, E.J.; Awais, M.; Mathiyalagan, R.; Han, Y.; Kang, J.; Yang, D.C.; Kang, S.C. Role of ginsenosides in browning of white adipose tissue to combat obesity: A narrative review on molecular mechanism. Arch. Med. Res. 2022, 53, 231–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zenk, J.L.; Leikam, S.A.; Kassen, L.J.; Kuskowski, M.A. Effect of lean system 7 on metabolic rate and body composition. Nutrition 2005, 21, 179–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.H.; Yi, Y.-S.; Kim, M.-Y.; Cho, J.Y. Role of ginsenosides, the main active components of Panax ginseng, in inflammatory responses and diseases. J. Ginseng Res. 2017, 41, 435–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yea, K.; Kim, J.; Lim, S.; Park, H.S.; Park, K.S.; Suh, P.-G.; Ryu, S.H. Lysophosphatidic acid regulates blood glucose by stimulating myotube and adipocyte glucose uptake. J. Mol. Med. 2008, 86, 211–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jose, A.; Kienesberger, P.C. Autotaxin-LPA-LPP3 axis in energy metabolism and metabolic disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 9575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.; Yang, X.; Hu, M.; Shao, Q.; Fang, K.; Li, J.; Zhao, Y.; Xu, L.; Zou, X.; Lu, F. Wu-Mei-Wan prevents high-fat diet-induced obesity by reducing white adipose tissue and enhancing brown adipose tissue function. Phytomedicine 2020, 76, 153258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Xu, M.; Zhou, M.; He, Y.; Li, Y.; Lang, H.; Wei, X.; Yan, L.; Xu, H. Hibiscus manihot L improves obesity in mice induced by a high-fat diet. J. Funct. Foods 2022, 89, 104953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.-H.; Park, S.-H.; Lee, E.; Seo, H.-D.; Ahn, J.; Jang, Y.-J.; Ha, T.-Y.; Im, S.S.; Jung, C.H. Withaferin A exerts an anti-obesity effect by increasing energy expenditure through thermogenic gene expression in high-fat diet-fed obese mice. Phytomedicine 2021, 82, 153457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, E.; Yang, X.; Huang, X.; Mi, Y.; Wu, X.; Fang, M.; Huang, J.; Qiu, Y.; Hong, X.; Peng, L. Phytochemical wedelolactone reverses obesity by prompting adipose browning through SIRT1/AMPK/PPARα pathway via targeting nicotinamide N-methyltransferase. Phytomedicine 2022, 94, 153843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grabner, G.F.; Xie, H.; Schweiger, M.; Zechner, R. Lipolysis: Cellular mechanisms for lipid mobilization from fat stores. Nat. Metab. 2021, 3, 1445–1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morak, M.; Schmidinger, H.; Riesenhuber, G.; Rechberger, G.N.; Kollroser, M.; Haemmerle, G.; Zechner, R.; Kronenberg, F.; Hermetter, A. Adipose triglyceride lipase (ATGL) and hormone-sensitive lipase (HSL) deficiencies affect expression of lipolytic activities in mouse adipose tissues. Mol. Cell. Proteom. 2012, 11, 1777–1789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Agellon, L.B.; Allen, T.M.; Umeda, M.; Jewell, L.; Mason, A.; Vance, D.E. The ratio of phosphatidylcholine to phosphatidylethanolamine influences membrane integrity and steatohepatitis. Cell Metab. 2006, 3, 321–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abobeleira, J.P.; Neto, A.C.; Mauersberger, J.; Salazar, M.; Botelho, M.; Fernandes, A.S.; Martinho, M.; Serrão, M.P.; Rodrigues, A.R.; Almeida, H. Evidence of browning and inflammation features in visceral adipose tissue of women with endometriosis. Arch. Med. Res. 2024, 55, 103064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.-E.; Ge, K. Transcriptional and epigenetic regulation of PPARγ expression during adipogenesis. Cell Biosci. 2014, 4, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavaldà-Navarro, A.; Villarroya, J.; Cereijo, R.; Giralt, M.; Villarroya, F. The endocrine role of brown adipose tissue: An update on actors and actions. Rev. Endocr. Metab. Disord. 2022, 23, 31–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, S.; Park, J.; Um, J.-Y. Ginsenoside Rb1 induces beta 3 adrenergic receptor–dependent lipolysis and thermogenesis in 3T3-L1 adipocytes and db/db mice. Front. Pharmacol. 2019, 10, 1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Lipid Component | Gintonin-Enriched Fraction (% w/w) | KRGM-Gintonin (% w/w) |

|---|---|---|

| Lysophosphatidic acid C18:2 | ~0.20% | ~0.27% |

| Lysophosphatidylcholine C18:2 | ~0.082% | ~0.99% |

| Phosphatidylcholine C16:0–18:2 | ~0.028% | ~1.38% |

| Phosphatidylcholine C18:2–18:2 | ~0.23% | ~1.48% |

| Name | Forward | Reverse |

|---|---|---|

| UCP1 | TCTCAGCCGGCTTAATGACT | TGCATTCTGACCTTCACGAC |

| PGC1-α | GTCAACAGCAAAAGCCACAA | GTGTGAGGAGGGTCATCGTT |

| PPAR-γ | ACGATCTGCCTGAGGTCTGT | CATCGAGGACATCCAAGACA |

| PPAR-α | TCGGACTCGGTCTTCTTGAT | TCTTCCCAAAGCTCCTTCAA |

| PPAR-β | TGGAGCTCGATGACAGTGAC | GGTTGACCTGCAGATGGAAT |

| TNF-α | CAGGCGGTGCCTATGTCTC | CGATCACCCCGAAGTTCAGTAG |

| Gab2 | TCTGAGACTGATAACGAGGAT | GATGGAGTCGGCTGTTG |

| IL-1β | AGATGAAGGGCTGCTTCCAAA | GGAAGGTCCACGGGAAAGAC |

| IL-6 | CTGCAAGAGACTTCCATCCAG | AGTGGTATAGACAGGTCTGTTGG |

| ATGL | CAACGCCACTCACATCTACGG | GGACACCTCAATAATGTTGGCAC |

| HSL | CCCCTGCGACGATTATCAAGA | CAGTGGCTGATGCAGTTATGTT |

| AMPK | GTGGTGTTATCCTGTATGCCCTTCT | CTGTTTAAACCATTCATGCTCTCGT |

| β-actin | CTCCGGCATGTGCAA | CCCACCATCACACCCT |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yasmin, T.; Lee, Y.; Kim, W.S.; Lee, B.; Lee, R.; Hwang, H.; Nam, M.-H.; Nah, S.-Y.; Kim, M.S.; Rhim, H. Lipid-Enriched Gintonin from Korean Red Ginseng Marc Alleviates Obesity via Oral and Central Administration in Diet-Induced Obese Mice. Nutrients 2025, 17, 3794. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17233794

Yasmin T, Lee Y, Kim WS, Lee B, Lee R, Hwang H, Nam M-H, Nah S-Y, Kim MS, Rhim H. Lipid-Enriched Gintonin from Korean Red Ginseng Marc Alleviates Obesity via Oral and Central Administration in Diet-Induced Obese Mice. Nutrients. 2025; 17(23):3794. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17233794

Chicago/Turabian StyleYasmin, Tamanna, Yuna Lee, Won Seok Kim, Bonggi Lee, Rami Lee, Hongik Hwang, Min-Ho Nam, Seung-Yeol Nah, Min Soo Kim, and Hyewhon Rhim. 2025. "Lipid-Enriched Gintonin from Korean Red Ginseng Marc Alleviates Obesity via Oral and Central Administration in Diet-Induced Obese Mice" Nutrients 17, no. 23: 3794. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17233794

APA StyleYasmin, T., Lee, Y., Kim, W. S., Lee, B., Lee, R., Hwang, H., Nam, M.-H., Nah, S.-Y., Kim, M. S., & Rhim, H. (2025). Lipid-Enriched Gintonin from Korean Red Ginseng Marc Alleviates Obesity via Oral and Central Administration in Diet-Induced Obese Mice. Nutrients, 17(23), 3794. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17233794