Linking Personality Traits to Mediterranean Diet Adherence and Exploring Gene–Diet Interactions in Neuroticism

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Personality Measurement and Assessment

1.2. Personality Traits and Nutrition

1.3. Genetics of Personality Traits: Focus on Neuroticism

1.4. Gene–Environment Interactions in Neuroticism

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Participants

2.2. Baseline Demographic, Lifestyle, Clinical, Anthropometric, Biochemical, and Lifestyle Variables

2.3. Adherence to the Mediterranean Diet

2.4. Personality Traits Assessment

2.5. DNA Isolation and Genome-Wide Genotyping

2.6. Statistical Analysis

2.6.1. Associations Between Personality Traits and Adherence to Mediterranean Diet

2.6.2. Associations Between Genetics and Neuroticism

2.6.3. Exploratory Analysis of Gene–Mediterranean Diet Interactions on Neuroticism

2.6.4. General Statistical Considerations

3. Results

3.1. General Characteristics of Study Participants Including Personality Traits

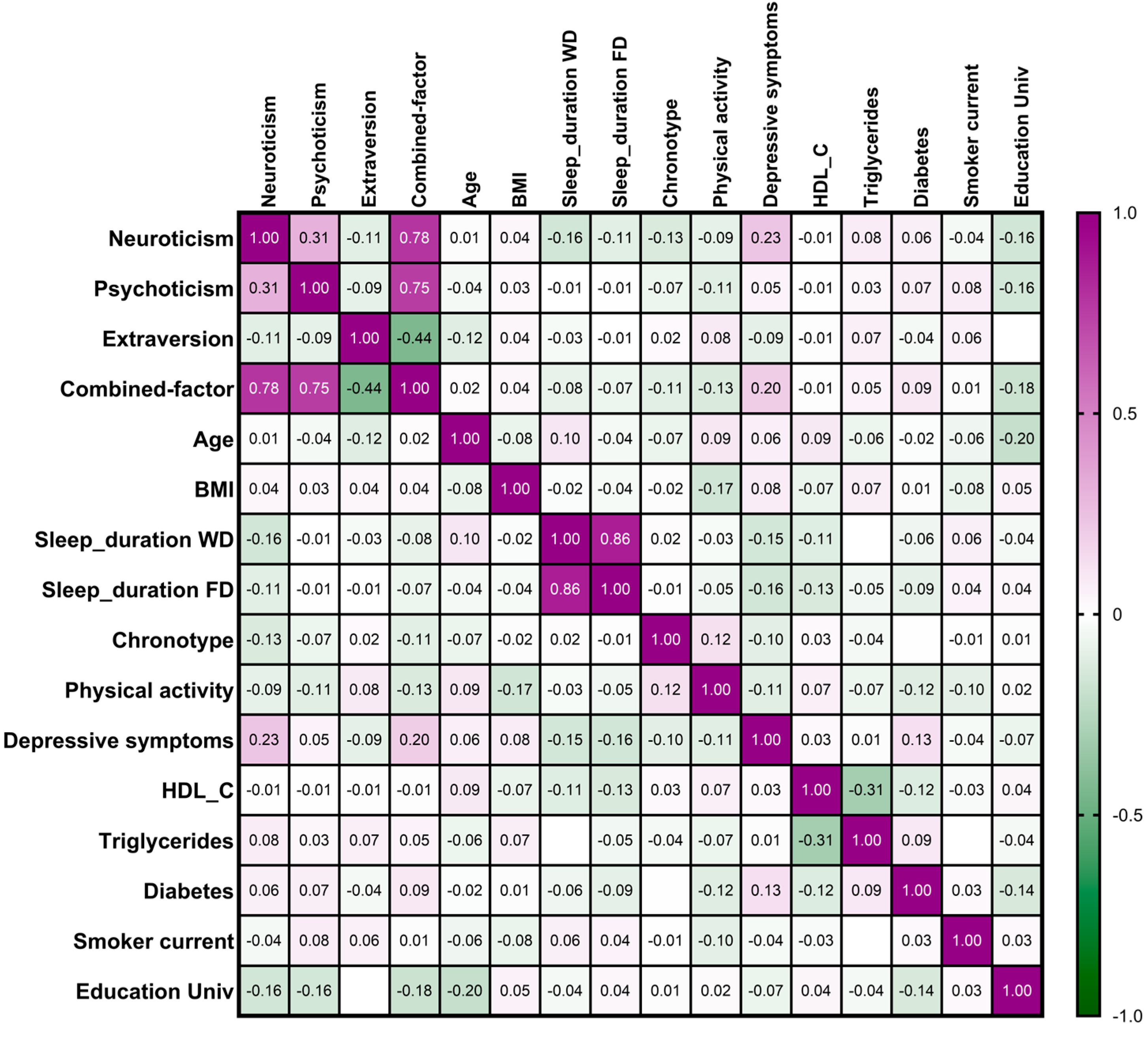

3.2. Combined Factor for Personality Traits and Association Between Personality Traits and Demographic, Lifestyle, and Clinical Variables

3.3. Associations Between Personality Traits and Adherence to the Mediterranean Diet

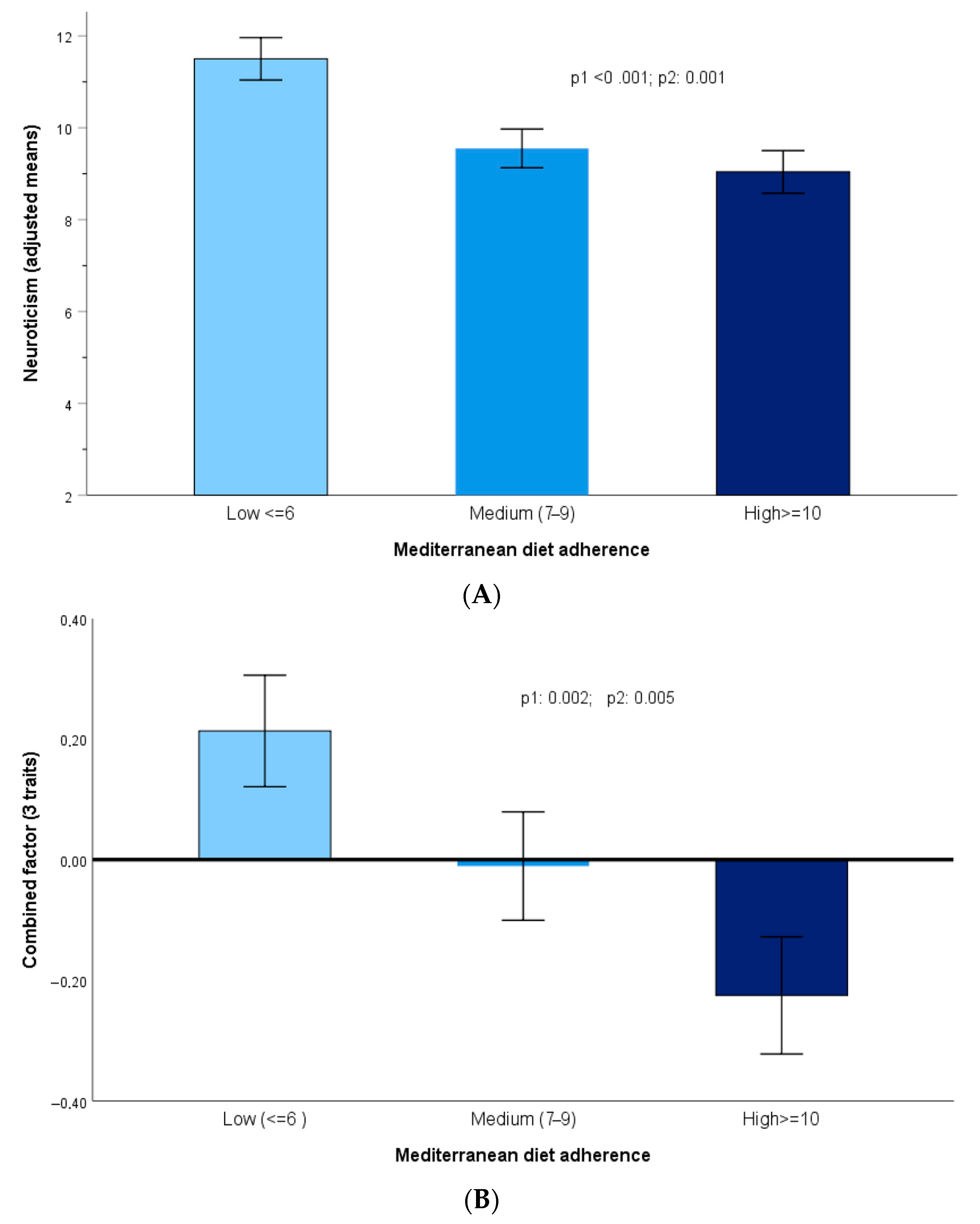

3.4. Adherence to Mediterranean Diet and Personality Traits

3.5. Genetic Factors Associated with Neuroticism: Exploratory GWAS

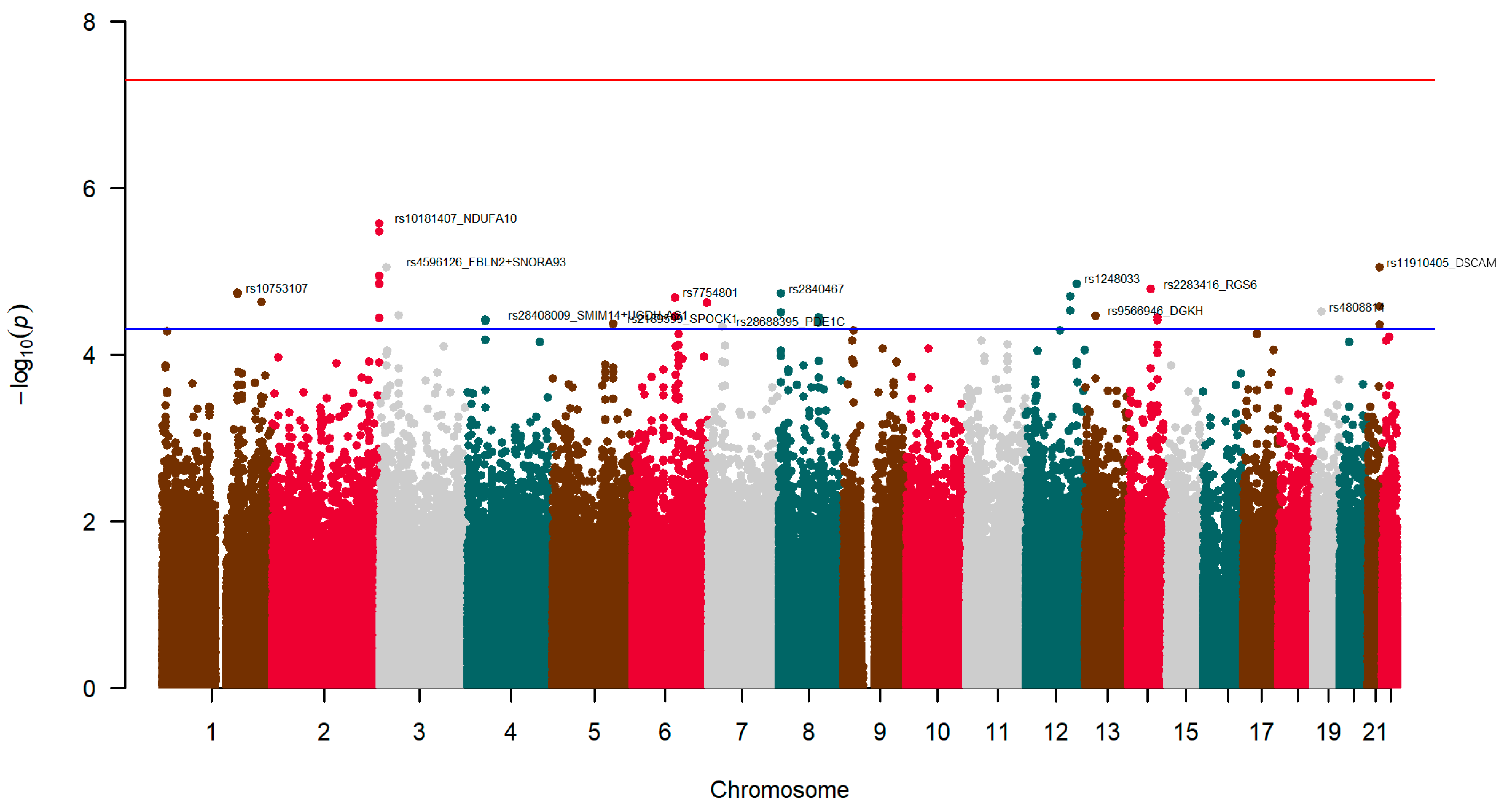

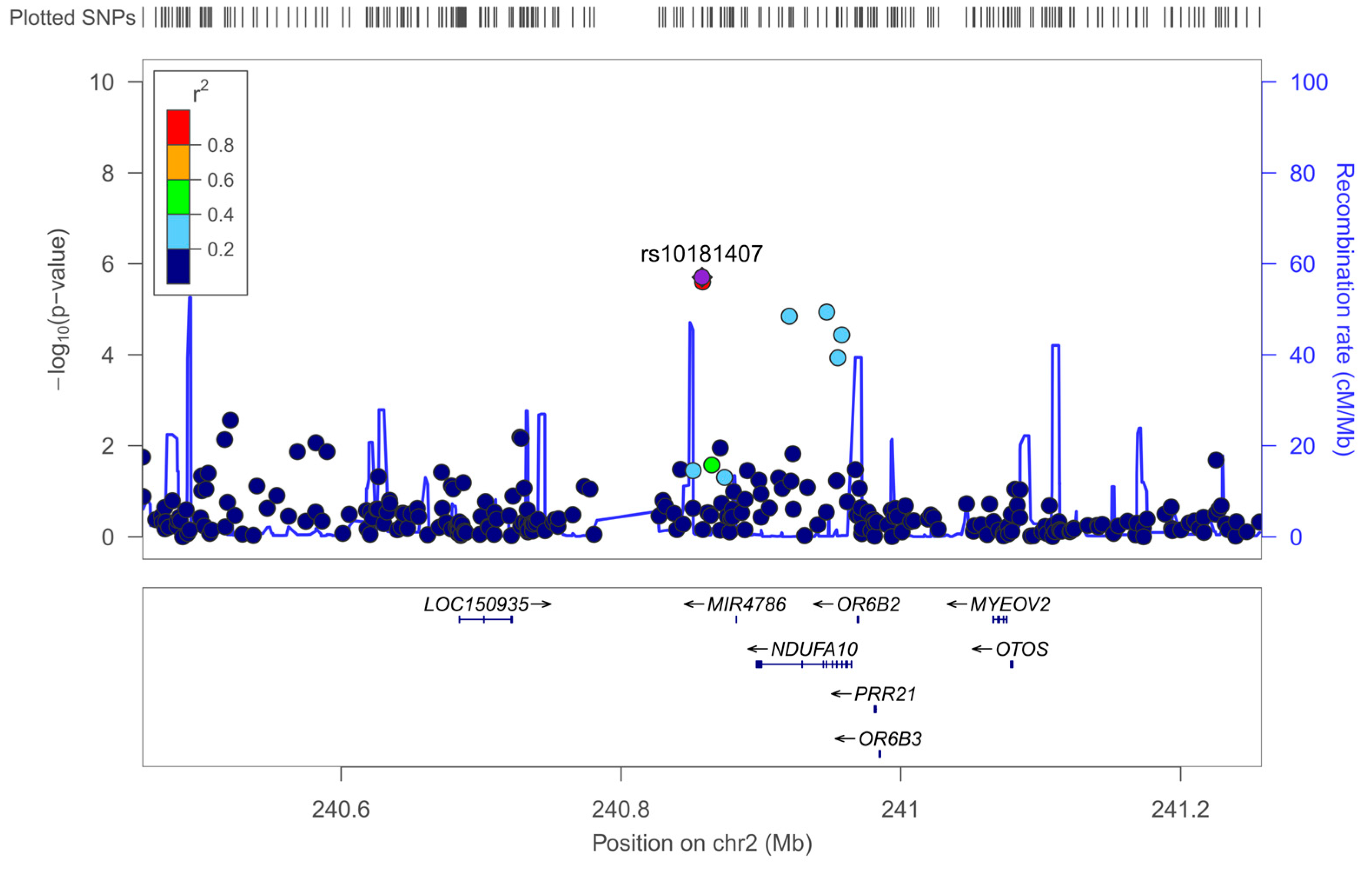

3.5.1. Exploratory GWAS for Neuroticism

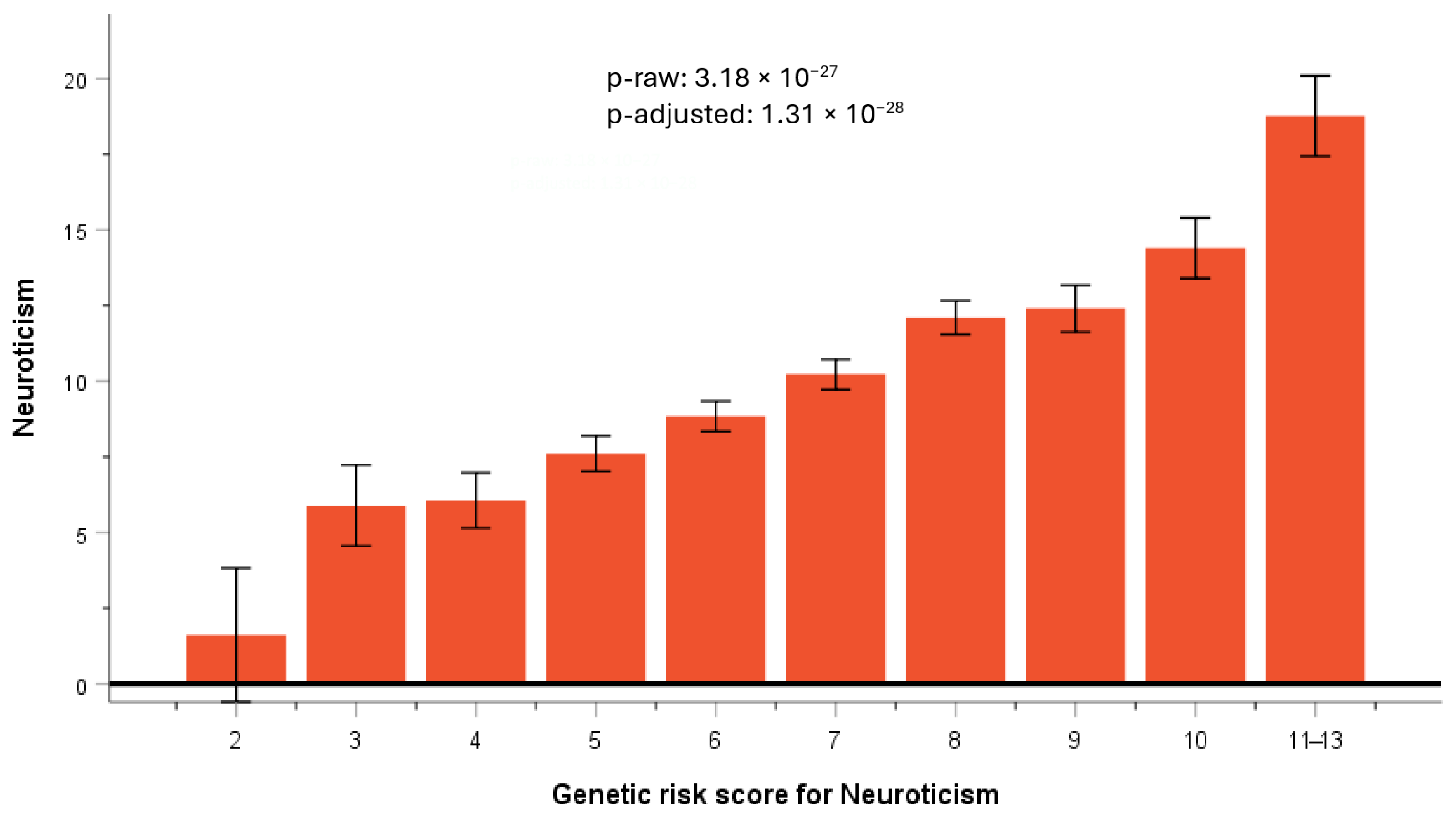

3.5.2. GRS for Neuroticism

3.5.3. Testing for Replication of SNP Previously Reported to Be Associated with Neuroticism

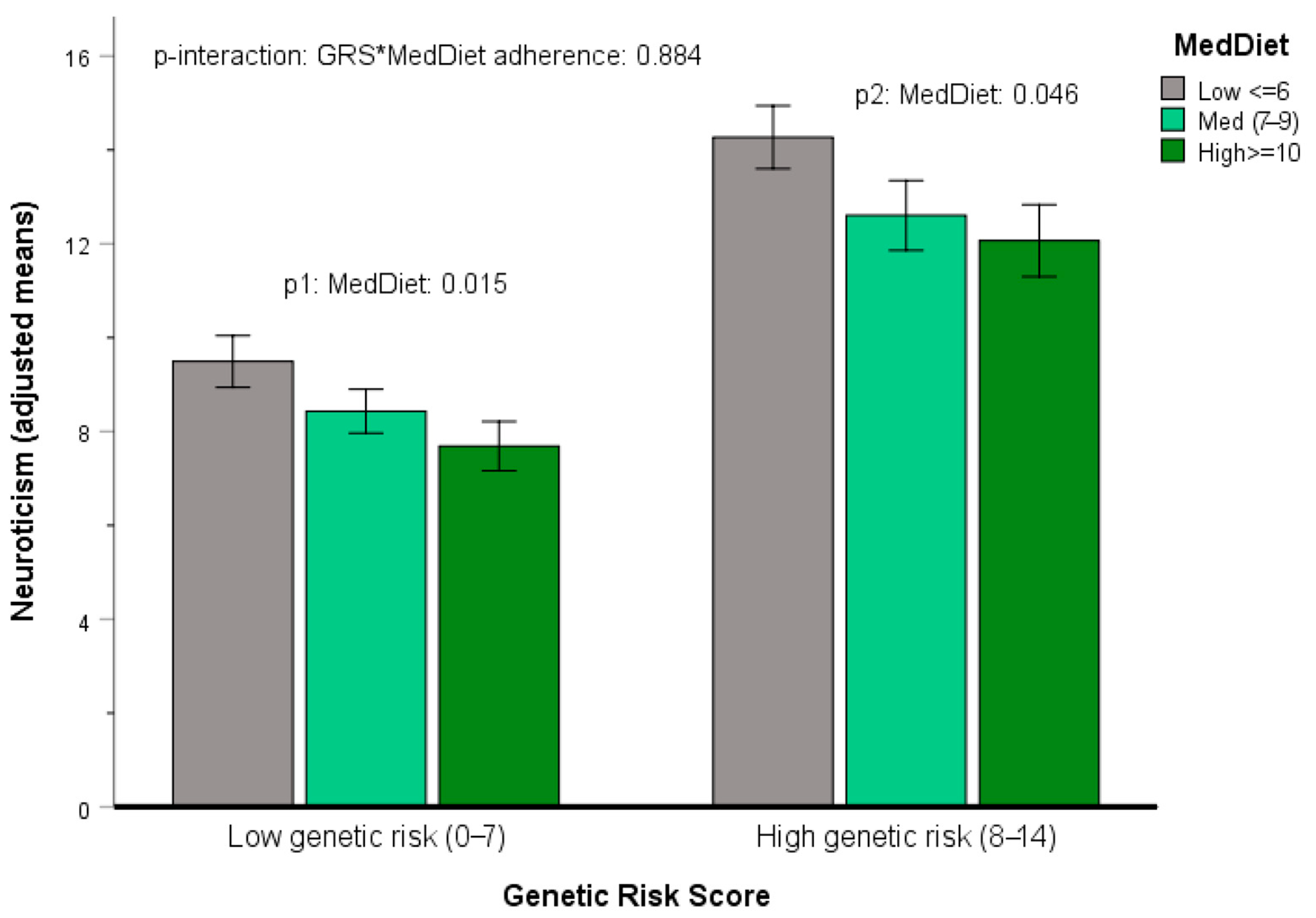

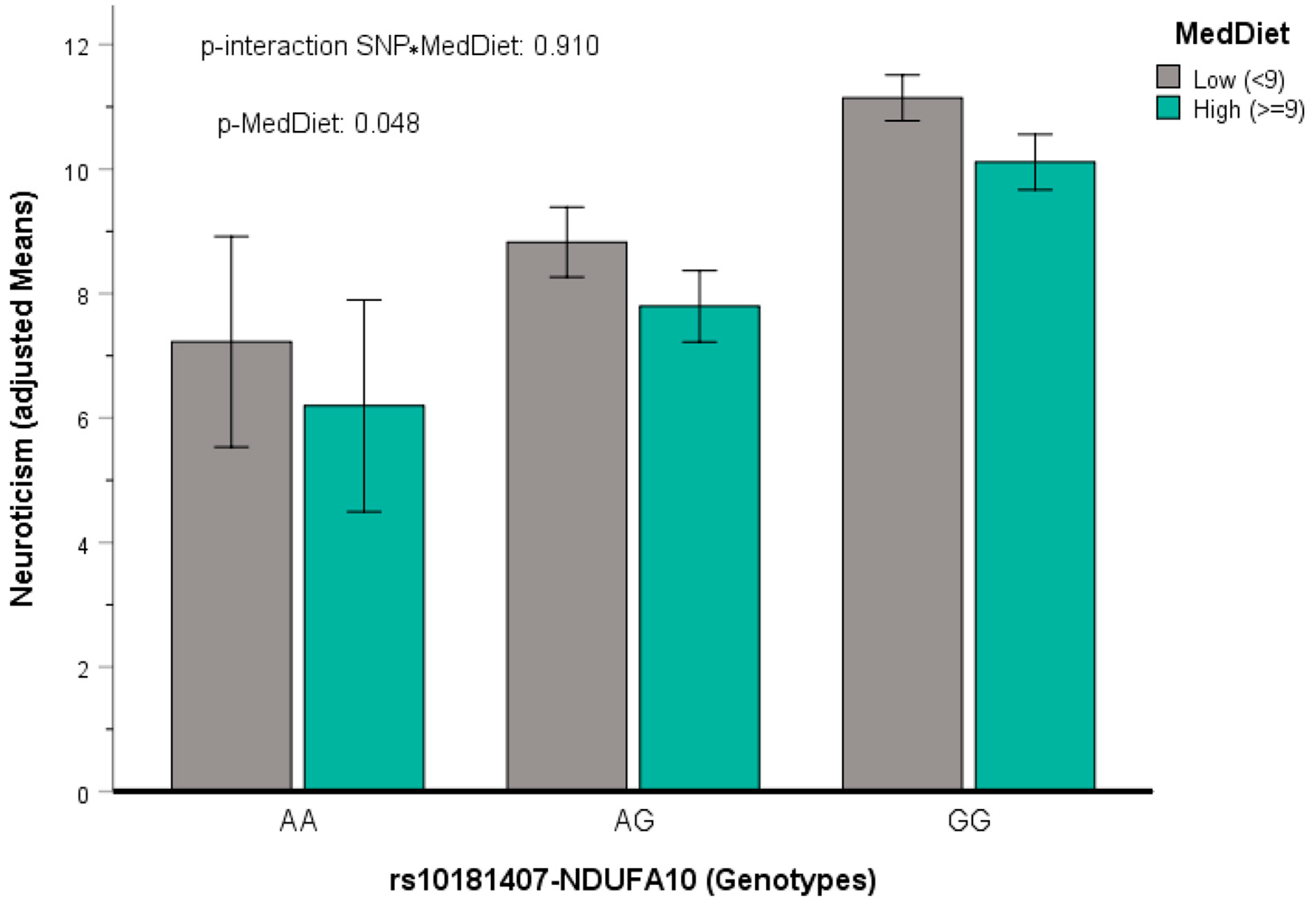

3.5.4. Gene x Mediterranean Diet Interactions in Determining Neuroticism

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ulusoy-Gezer, H.G.; Rakıcıoğlu, N. The Future of Obesity Management through Precision Nutrition: Putting the Individual at the Center. Curr. Nutr. Rep. 2024, 13, 455–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biruete, A.; Buobu, P.S.; Considine, R.; Hoxha, E.M.; Eicher-Miller, H.A.; Kinzig, K.P.; Panjwani, A.A.; Running, C.A.; Rutigliani, G.; Savaiano, D.A.; et al. Ingestive Behavior and Precision Nutrition: Part of the Puzzle. Adv. Nutr. 2025, 16, 100531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkerwi, A.; Sauvageot, N.; Nau, A.; Lair, M.-L.; Donneau, A.-F.; Albert, A.; Guillaume, M. Population Compliance with National Dietary Recommendations and Its Determinants: Findings from the ORISCAV-LUX Study. Br. J. Nutr. 2012, 108, 2083–2092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Abreu, D.; Guessous, I.; Vaucher, J.; Preisig, M.; Waeber, G.; Vollenweider, P.; Marques-Vidal, P. Low Compliance with Dietary Recommendations for Food Intake among Adults. Clin. Nutr. 2013, 32, 783–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobiac, L.; Irz, X.; Leroy, P.; Réquillart, V.; Scarborough, P.; Soler, L.-G. Accounting for Consumers’ Preferences in the Analysis of Dietary Recommendations. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2019, 73, 1033–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuber, J.M.; Lakerveld, J.; Beulens, J.W.; Mackenbach, J.D. Better Understanding Determinants of Dietary Guideline Adherence among Dutch Adults with Varying Socio-Economic Backgrounds through a Mixed-Methods Exploration. Public Health Nutr. 2023, 26, 1172–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, H. Factors Influencing Dietary Compliance among Patients with Gestational Diabetes Mellitus: A Retrospective Analysis. Am. J. Transl. Res. 2025, 17, 1925–1937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esposito, C.M.; Ceresa, A.; Buoli, M. The Association Between Personality Traits and Dietary Choices: A Systematic Review. Adv. Nutr. 2021, 12, 1149–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golestanbagh, N.; Miraghajani, M.; Amani, R.; Symonds, M.E.; Neamatpour, S.; Haghighizadeh, M.H. Association of Personality Traits with Dietary Habits and Food/Taste Preferences. Int. J. Prev. Med. 2021, 12, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfeiler, T.M.; Egloff, B. Personality and Eating Habits Revisited: Associations between the Big Five, Food Choices, and Body Mass Index in a Representative Australian Sample. Appetite 2020, 149, 104607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, M.S.; Mishra, M.; Tashjian, S.M.; Laborde, S. Linking Big Five Personality Traits to Components of Diet: A Meta-Analytic Review. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2025, 128, 905–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Micheli, M.; Takousi, M.; Skordis, M.; Kalogirou, A.; Karpodini, C.C.; Giannopoulou, C.S.; Koutoulogenis, K.; Fappa, E. Associations between Dietary Patterns Derived Using Principal Component Analysis and Personality Traits in Adults: A Cross-Sectional Study. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2025, 76, 654–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergner, R.M. What Is Personality? Two Myths and a Definition. New Ideas Psychol. 2020, 57, 100759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tlili, A.; Sun, T.; Denden, M.; Kinshuk; Graf, S.; Fei, C.; Wang, H. Impact of Personality Traits on Learners’ Navigational Behavior Patterns in an Online Course: A Lag Sequential Analysis Approach. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1071985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gustavsson, J.P.; Jönsson, E.G.; Linder, J.; Weinryb, R.M. The HP5 Inventory: Definition and Assessment of Five Health-Relevant Personality Traits from a Five-Factor Model Perspective. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2003, 35, 69–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuper, N.; Modersitzki, N.; Phan, L.V.; Rauthmann, J.F. The Dynamics, Processes, Mechanisms, and Functioning of Personality: An Overview of the Field. Br. J. Psychol. 2021, 112, 1–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, B.W.; Yoon, H.J. Personality Psychology. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2022, 73, 489–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saggino, A. The Big Three or the Big Five? A Replication Study. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2000, 28, 879–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Columbus, S.; Strandsbjerg, C.F. Personality States. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2025, 65, 102099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, H.; Jia, F.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, R. The Relationship Between the Big Five Personality Model and Innovation Behavior: A Three-Level Meta-Analysis. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khazaie, H.; Komasi, S.; Zakiei, A.; Khazaie, A.; Sharafkhaneh, A. A Meta-Analytic Review of the Associations of the Big Five Personality Traits with Subjective Poor Sleep Quality and Insomnia, and Meta-Regression of Some Potential Moderators. Int. J. Behav. Med. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.; Hao, G.; Xiao, L.; Luo, S.; Zhang, G.; Tang, X.; Qu, P.; Li, R. Association Between Extraversion Personality with the Blood Pressure Level in Adolescents. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2022, 9, 711474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, X.Y.; Jin, J. Personality Risk Factors of Occurrence of Female Breast Cancer: A Case-Control Study in China. Psychol. Health Med. 2018, 23, 1239–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eysenck, S.B.G.; Eysenck, H.J. Scores on Three Personality Variables as a Function of Age, Sex and Social Class. Br. J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 1969, 8, 69–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCrae, R.R.; John, O.P. An Introduction to the Five-Factor Model and Its Applications. J. Personal. 1992, 60, 175–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeBlanc, J.; Ducharme, M.B.; Thompson, M. Study on the Correlation of the Autonomic Nervous System Responses to a Stressor of High Discomfort with Personality Traits. Physiol. Behav. 2004, 82, 647–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, W.; Song, L.; Du, J.; Li, X.; Wang, H.; Cheng, L.; Li, J.; Zhang, L.; Li, X.; Yang, Q.; et al. The Similarity Between Chinese Five-Pattern and Eysenck’s Personality Traits: Evidence from Theory and Resting-State fMRI. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2020, 14, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.; Wang, T.; Cai, Z. Exploring the Impact of the Big Five Personality Traits on Cognitive Performance in Scientific Reasoning: An Ordered Network Analysis. Cogn. Process 2025, 26, 849–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoon, I. Towards an Integrative Taxonomy of Social-Emotional Competences. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 515313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, A.; Luciano, M.; Aluja, A. Associations Between a General Factor and Group Factor from the Spanish-Language Eysenck Personality Questionnaire–Revised Short Form’s Neuroticism Scale and the Revised NEO Personality Inventory Domains and Facets. J. Personal. Assess. 2024, 106, 584–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Sun, J.; Wu, C.; Ma, Z.; Shen, C.; Hu, W.; Lang, H. Relationships Between Burnout and Neuroticism Among Emergency Department Nurses: A Network Analysis. Nurs. Open 2024, 11, e70067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, P.T.; McCrae, R.R. Primary Traits of Eysenck’s P-E-N System: Three- and Five-Factor Solutions. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1995, 69, 308–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Connor, B.P. A Quantitative Review of the Comprehensiveness of the Five-Factor Model in Relation to Popular Personality Inventories. Assessment 2002, 9, 188–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicentini, G.; Raccanello, D.; Burro, R. Self-Report Questionnaires to Measure Big Five Personality Traits in Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review. Scand. J. Psychol. 2025, 66, 627–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheibe, V.M.; Brenner, A.M.; De Souza, G.R.; Menegol, R.; Almiro, P.A.; Da Rocha, N.S. The Eysenck Personality Questionnaire Revised–Abbreviated (EPQR-A): Psychometric Properties of the Brazilian Portuguese Version. Trends Psychiatry Psychother. 2023, 45, e20210342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortet, G.; Martínez, T.; Mezquita, L.; Morizot, J.; Ibáñez, M.I. Big Five Personality Trait Short Questionnaire: Preliminary Validation with Spanish Adults. Span. J. Psychol. 2017, 20, E7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa Mastrascusa, R.; De Oliveira Fenili Antunes, M.L.; De Albuquerque, N.S.; Virissimo, S.L.; Foletto Moura, M.; Vieira Marques Motta, B.; De Lara Machado, W.; Moret-Tatay, C.; Quarti Irigaray, T. Evaluating the Complete (44-Item), Short (20-Item) and Ultra-Short (10-Item) Versions of the Big Five Inventory (BFI) in the Brazilian Population. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 7372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lignier, B.; Petot, J.-M.; De Oliveira, P.; Nicolas, M.; Canada, B.; Courtois, R.; John, O.P.; Plaisant, O.; Soto, C.J. Factor Structure and Psychometric Properties of the French Versions of the Big Five Inventory-2 Short (BFI-2-S) and Extra-Short (BFI-2-XS) Forms. L’Encéphale 2025, 51, 601–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Torres, F.; Castillo-Mayén, R. Differences in Eysenck’s Personality Dimensions between a Group of Breast Cancer Survivors and the General Population. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colledani, D.; Anselmi, P.; Robusto, E. Development of a New Abbreviated Form of the Eysenck Personality Questionnaire-Revised with Multidimensional Item Response Theory. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2019, 149, 108–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sariyska, R.; Markett, S.; Lachmann, B.; Montag, C. What Does Our Personality Say About Our Dietary Choices? Insights on the Associations Between Dietary Habits, Primary Emotional Systems and the Dark Triad of Personality. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 2591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perälä, M.-M.; Tiainen, A.-M.; Lahti, J.; Männistö, S.; Lahti, M.; Heinonen, K.; Kaartinen, N.E.; Pesonen, A.-K.; Kajantie, E.; Räikkönen, K.; et al. Food and Nutrient Intakes by Temperament Traits: Findings in the Helsinki Birth Cohort Study. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2018, 72, 1136–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holler, S.; Cramer, H.; Liebscher, D.; Jeitler, M.; Schumann, D.; Murthy, V.; Michalsen, A.; Kessler, C.S. Differences Between Omnivores and Vegetarians in Personality Profiles, Values, and Empathy: A Systematic Review. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 579700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kessler, C.S.; Holler, S.; Joy, S.; Dhruva, A.; Michalsen, A.; Dobos, G.; Cramer, H. Personality Profiles, Values and Empathy: Differences between Lacto-Ovo-Vegetarians and Vegans. Complement. Med. Res. 2016, 23, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reist, M.E.; Bleidorn, W.; Milfont, T.L.; Hopwood, C.J. Meta-Analysis of Personality Trait Differences between Omnivores, Vegetarians, and Vegans. Appetite 2023, 191, 107085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farhan, L.; Hange, D.; Hällström, T.; Björkelund, C.; Lissner, L.; Stahre, L.; Mehlig, K. Personality, Eating Behaviour, and Body Weight: Results from the Population Study of Women in Gothenburg 2016/17. Int. J. Obes. 2025, 49, 1272–1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurado, D.; Burgos-Garrido, E.; Diaz, F.J.; Martínez-Ortega, J.M.; Gurpegui, M. Adherence to the Mediterranean Dietary Pattern and Personality in Patients Attending a Primary Health Center. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2012, 112, 887–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mõttus, R.; McNeill, G.; Jia, X.; Craig, L.C.A.; Starr, J.M.; Deary, I.J. The Associations between Personality, Diet and Body Mass Index in Older People. Health Psychol. 2013, 32, 353–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yañez, A.M.; Bennasar-Veny, M.; Leiva, A.; García-Toro, M. Implications of Personality and Parental Education on Healthy Lifestyles among Adolescents. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 7911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schröder, H.; Fitó, M.; Estruch, R.; Martínez-González, M.A.; Corella, D.; Salas-Salvadó, J.; Lamuela-Raventós, R.; Ros, E.; Salaverría, I.; Fiol, M.; et al. A Short Screener Is Valid for Assessing Mediterranean Diet Adherence among Older Spanish Men and Women. J. Nutr. 2011, 141, 1140–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serra-Majem, L.; Ribas, L.; Ngo, J.; Ortega, R.M.; García, A.; Pérez-Rodrigo, C.; Aranceta, J. Food, Youth and the Mediterranean Diet in Spain. Development of KIDMED, Mediterranean Diet Quality Index in Children and Adolescents. Public Health Nutr. 2004, 7, 931–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gutiérrez-Zotes, J.A.; Cortés, M.J.; Valero, J.; Peña, J.; Labad, A. Psychometric Properties of the Abbreviated Spanish Version of TCI-R (TCI-140) and Its Relationship with the Psychopathological Personality Scales (MMPI-2 PSY-5) in Patients. Actas Esp. Psiquiatr. 2005, 33, 231–237. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Terracciano, A.; Sanna, S.; Uda, M.; Deiana, B.; Usala, G.; Busonero, F.; Maschio, A.; Scally, M.; Patriciu, N.; Chen, W.-M.; et al. Genome-Wide Association Scan for Five Major Dimensions of Personality. Mol. Psychiatry 2010, 15, 647–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munafò, M.R.; Flint, J. Dissecting the Genetic Architecture of Human Personality. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2011, 15, 395–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Roige, S.; Gray, J.C.; MacKillop, J.; Chen, C.-H.; Palmer, A.A. The Genetics of Human Personality. Genes Brain Behav. 2018, 17, e12439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, P.; Galimberti, M.; Liu, Y.; Beck, S.; Wingo, A.; Wingo, T.; Adhikari, K.; Kranzler, H.R.; VA Million Veteran Program; Stein, M.B.; et al. A Genome-Wide Investigation into the Underlying Genetic Architecture of Personality Traits and Overlap with Psychopathology. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2024, 8, 2235–2249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- 23andMe Research Team; Nagel, M.; Jansen, P.R.; Stringer, S.; Watanabe, K.; De Leeuw, C.A.; Bryois, J.; Savage, J.E.; Hammerschlag, A.R.; Skene, N.G.; et al. Meta-Analysis of Genome-Wide Association Studies for Neuroticism in 449,484 Individuals Identifies Novel Genetic Loci and Pathways. Nat. Genet. 2018, 50, 920–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Moor, M.H.M.; Van Den Berg, S.M.; Verweij, K.J.H.; Krueger, R.F.; Luciano, M.; Arias Vasquez, A.; Matteson, L.K.; Derringer, J.; Esko, T.; Amin, N.; et al. Meta-Analysis of Genome-Wide Association Studies for Neuroticism, and the Polygenic Association with Major Depressive Disorder. JAMA Psychiatry 2015, 72, 642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, H.T.; Sebastiani, P.; Sun, J.X.; Andersen, S.L.; Daw, E.W.; Terracciano, A.; Ferrucci, L.; Perls, T.T. Genome-Wide Association Study of Personality Traits in the Long Life Family Study. Front. Genet. 2013, 4, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.-H.; Kim, H.-N.; Roh, S.-J.; Lee, M.K.; Yang, S.; Lee, S.K.; Sung, Y.-A.; Chung, H.W.; Cho, N.H.; Shin, C.; et al. GWA Meta-Analysis of Personality in Korean Cohorts. J. Hum. Genet. 2015, 60, 455–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, M.-T.; Hinds, D.A.; Tung, J.Y.; Franz, C.; Fan, C.-C.; Wang, Y.; Smeland, O.B.; Schork, A.; Holland, D.; Kauppi, K.; et al. Genome-Wide Analyses for Personality Traits Identify Six Genomic Loci and Show Correlations with Psychiatric Disorders. Nat. Genet. 2017, 49, 152–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, D.J.; Escott-Price, V.; Davies, G.; Bailey, M.E.S.; Colodro-Conde, L.; Ward, J.; Vedernikov, A.; Marioni, R.; Cullen, B.; Lyall, D.; et al. Genome-Wide Analysis of over 106 000 Individuals Identifies 9 Neuroticism-Associated Loci. Mol. Psychiatry 2016, 21, 749–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Docherty, A.R.; Moscati, A.; Peterson, R.; Edwards, A.C.; Adkins, D.E.; Bacanu, S.A.; Bigdeli, T.B.; Webb, B.T.; Flint, J.; Kendler, K.S. SNP-Based Heritability Estimates of the Personality Dimensions and Polygenic Prediction of Both Neuroticism and Major Depression: Findings from CONVERGE. Transl. Psychiatry 2016, 6, e926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luciano, M.; Hagenaars, S.P.; Davies, G.; Hill, W.D.; Clarke, T.-K.; Shirali, M.; Harris, S.E.; Marioni, R.E.; Liewald, D.C.; Fawns-Ritchie, C.; et al. Association Analysis in over 329,000 Individuals Identifies 116 Independent Variants Influencing Neuroticism. Nat. Genet. 2018, 50, 6–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heilbronner, U.; Papiol, S.; Budde, M.; Andlauer, T.F.M.; Strohmaier, J.; Streit, F.; Frank, J.; Degenhardt, F.; Heilmann-Heimbach, S.; Witt, S.H.; et al. “The Heidelberg Five” Personality Dimensions: Genome-wide Associations, Polygenic Risk for Neuroticism, and Psychopathology 20 Years after Assessment. Am. J. Med. Genet. Pt. B 2021, 186, 77–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belonogova, N.M.; Zorkoltseva, I.V.; Tsepilov, Y.A.; Axenovich, T.I. Gene-Based Association Analysis Identifies 190 Genes Affecting Neuroticism. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 2484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zmorzyński, S.; Styk, W.; Klinkosz, W.; Iskra, J.; Filip, A.A. Personality Traits and Polymorphisms of Genes Coding Neurotransmitter Receptors or Transporters: Review of Single Gene and Genome-Wide Association Studies. Ann. Gen. Psychiatry 2021, 20, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kandler, C.; Bleidorn, W.; Riemann, R.; Angleitner, A.; Spinath, F.M. Life Events as Environmental States and Genetic Traits and the Role of Personality: A Longitudinal Twin Study. Behav. Genet. 2012, 42, 57–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avinun, R. The E Is in the G: Gene–Environment–Trait Correlations and Findings from Genome-Wide Association Studies. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2020, 15, 81–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werme, J.; Van Der Sluis, S.; Posthuma, D.; De Leeuw, C.A. Genome-Wide Gene-Environment Interactions in Neuroticism: An Exploratory Study across 25 Environments. Transl. Psychiatry 2021, 11, 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klingenberg, B.; Guloksuz, S.; Pries, L.-K.; Cinar, O.; Menne-Lothmann, C.; Decoster, J.; Van Winkel, R.; Collip, D.; Delespaul, P.; De Hert, M.; et al. Gene–Environment Interaction Study on the Polygenic Risk Score for Neuroticism, Childhood Adversity, and Parental Bonding. Personal. Neurosci. 2023, 6, e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Canela, M.; Corella, D.; Martínez-González, M.Á.; Babio, N.; Martínez, J.A.; Forga, L.; Alonso-Gómez, Á.M.; Wärnberg, J.; Vioque, J.; Romaguera, D.; et al. Comparison of an Energy-Reduced Mediterranean Diet and Physical Activity Versus an Ad Libitum Mediterranean Diet in the Prevention of Type 2 Diabetes: A Secondary Analysis of a Randomized Controlled Trial. Ann. Intern. Med. 2025, 178, 1378–1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sorlí, J.V.; De La Cámara, E.; Fernández-Carrión, R.; Asensio, E.M.; Portolés, O.; Ortega-Azorín, C.; Pérez-Fidalgo, A.; Villamil, L.V.; Fitó, M.; Barragán, R.; et al. Depression and Accelerated Aging: The Eveningness Chronotype and Low Adherence to the Mediterranean Diet Are Associated with Depressive Symptoms in Older Subjects. Nutrients 2024, 17, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina, L.; Sarmiento, M.; Peñafiel, J.; Donaire, D.; Garcia-Aymerich, J.; Gomez, M.; Ble, M.; Ruiz, S.; Frances, A.; Schröder, H.; et al. Validation of the Regicor Short Physical Activity Questionnaire for the Adult Population. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0168148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horne, J.; Ostberg, O. A Self-Assessment Questionnaire to Determine Morningness-Eveningness in Human Circadian Rhythms. Int. J. Chronobiol. 1976, 4, 97–110. [Google Scholar]

- Sanz Fernández, J.; Vázquez Valverde, C.; Perdigón, A. Adaptación Española Del Inventario Para La Depresión de Beck-II (BDI-II)2. Propiedades Psicométricas En Población General. Clínica Y Salud Investig. Empírica En. Psicol. 2003, 14, 249–280. [Google Scholar]

- Baenas, I.; Camacho-Barcia, L.; Granero, R.; Razquin, C.; Corella, D.; Gómez-Martínez, C.; Castañer-Niño, O.; Martínez, J.A.; Alonso-Gómez, Á.M.; Wärnberg, J.; et al. Association between Type 2 Diabetes and Depressive Symptoms after a 1-Year Follow-up in an Older Adult Mediterranean Population. J. Endocrinol. Investig. 2024, 47, 1405–1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schröder, H.; Zomeño, M.D.; Martínez-González, M.A.; Salas-Salvadó, J.; Corella, D.; Vioque, J.; Romaguera, D.; Martínez, J.A.; Tinahones, F.J.; Miranda, J.L.; et al. Validity of the Energy-Restricted Mediterranean Diet Adherence Screener. Clin. Nutr. 2021, 40, 4971–4979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ortet, G.; Ibáñez, M.; Moro, M.; Silva, F. Cuestionario Revisado de Personalidad de Eysenck: Versiones Completa (EPQ-R) y Abreviada (EPQ-RS), 3rd ed.; TEA: Madrid, Spain, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Santiago, D.; Montoro, C.I.; Davydov, D.M.; Reyes Del Paso, G.A. Personality Traits in Fibromyalgia: Aggravators and Attenuators of Clinical Symptoms and Medication Use. Behav. Neurol. 2025, 2025, 9961041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozamiz-Etxebarria, N.; Jiménez-Etxebarria, E.; Picaza, M.; Idoiaga, N. Quality of life and personality in older people university students. Rev. Esp. Salud Publica 2022, 96, e202209070. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Coltell, O.; Sorlí, J.V.; Asensio, E.M.; Fernández-Carrión, R.; Barragán, R.; Ortega-Azorín, C.; Estruch, R.; González, J.I.; Salas-Salvadó, J.; Lamon-Fava, S.; et al. Association between Taste Perception and Adiposity in Overweight or Obese Older Subjects with Metabolic Syndrome and Identification of Novel Taste-Related Genes. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2019, 109, 1709–1723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coltell, O.; Sorlí, J.V.; Asensio, E.M.; Barragán, R.; González, J.I.; Giménez-Alba, I.M.; Zanón-Moreno, V.; Estruch, R.; Ramírez-Sabio, J.B.; Pascual, E.C.; et al. Genome-Wide Association Study for Serum Omega-3 and Omega-6 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids: Exploratory Analysis of the Sex-Specific Effects and Dietary Modulation in Mediterranean Subjects with Metabolic Syndrome. Nutrients 2020, 12, 310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purcell, S.; Neale, B.; Todd-Brown, K.; Thomas, L.; Ferreira, M.A.R.; Bender, D.; Maller, J.; Sklar, P.; De Bakker, P.I.W.; Daly, M.J.; et al. PLINK: A Tool Set for Whole-Genome Association and Population-Based Linkage Analyses. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2007, 81, 559–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.C.; Chow, C.C.; Tellier, L.C.; Vattikuti, S.; Purcell, S.M.; Lee, J.J. Second-Generation PLINK: Rising to the Challenge of Larger and Richer Datasets. Gigascience 2015, 4, s13742-015-0047-0048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernández-Carrión, R.; Sorlí, J.V.; Coltell, O.; Pascual, E.C.; Ortega-Azorín, C.; Barragán, R.; Giménez-Alba, I.M.; Alvarez-Sala, A.; Fitó, M.; Ordovas, J.M.; et al. Sweet Taste Preference: Relationships with Other Tastes, Liking for Sugary Foods and Exploratory Genome-Wide Association Analysis in Subjects with Metabolic Syndrome. Biomedicines 2021, 10, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coltell, O.; Asensio, E.M.; Sorlí, J.V.; Barragán, R.; Fernández-Carrión, R.; Portolés, O.; Ortega-Azorín, C.; Martínez-LaCruz, R.; González, J.I.; Zanón-Moreno, V.; et al. Genome-Wide Association Study (GWAS) on Bilirubin Concentrations in Subjects with Metabolic Syndrome: Sex-Specific GWAS Analysis and Gene-Diet Interactions in a Mediterranean Population. Nutrients 2019, 11, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, S.D. Qqman: An R Package for Visualizing GWAS Results Using Q-Q and Manhattan Plots. J. Open Source Softw. 2018, 3, 731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pruim, R.J.; Welch, R.P.; Sanna, S.; Teslovich, T.M.; Chines, P.S.; Gliedt, T.P.; Boehnke, M.; Abecasis, G.R.; Willer, C.J. LocusZoom: Regional Visualization of Genome-Wide Association Scan Results. Bioinformatics 2010, 26, 2336–2337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, K.; Taskesen, E.; Van Bochoven, A.; Posthuma, D. Functional Mapping and Annotation of Genetic Associations with FUMA. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 1826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szkiba, D.; Kapun, M.; Von Haeseler, A.; Gallach, M. SNP2GO: Functional Analysis of Genome-Wide Association Studies. Genetics 2014, 197, 285–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hüls, A.; Krämer, U.; Carlsten, C.; Schikowski, T.; Ickstadt, K.; Schwender, H. Comparison of Weighting Approaches for Genetic Risk Scores in Gene-Environment Interaction Studies. BMC Genet. 2017, 18, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boef, A.G.C.; Dekkers, O.M.; Le Cessie, S. Mendelian Randomization Studies: A Review of the Approaches Used and the Quality of Reporting. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2015, 44, 496–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corella, D.; Ordovas, J.M. Nutrigenomics in Cardiovascular Medicine. Circ. Cardiovasc. Genet. 2009, 2, 637–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiainen, A.-M.K.; Männistö, S.; Lahti, M.; Blomstedt, P.A.; Lahti, J.; Perälä, M.-M.; Räikkönen, K.; Kajantie, E.; Eriksson, J.G. Personality and Dietary Intake–Findings in the Helsinki Birth Cohort Study. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e68284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conner, T.S.; Thompson, L.M.; Knight, R.L.; Flett, J.A.M.; Richardson, A.C.; Brookie, K.L. The Role of Personality Traits in Young Adult Fruit and Vegetable Consumption. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardebili, A.T.; Rickertsen, K. A Sustainable and Healthy Diet: Personality, Motives, and Sociodemographics. Heliyon 2024, 10, e31326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, C.; Siegrist, M. Does Personality Influence Eating Styles and Food Choices? Direct and Indirect Effects. Appetite 2015, 84, 128–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serra-Majem, L.; Román-Viñas, B.; Sanchez-Villegas, A.; Guasch-Ferré, M.; Corella, D.; La Vecchia, C. Benefits of the Mediterranean Diet: Epidemiological and Molecular Aspects. Mol. Asp. Med. 2019, 67, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widiger, T.A.; Oltmanns, J.R. Neuroticism Is a Fundamental Domain of Personality with Enormous Public Health Implications. World Psychiatry 2017, 16, 144–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahmood, A.; Simon, J.; Cooper, J.; Murphy, T.; McCracken, C.; Quiroz, J.; Laranjo, L.; Aung, N.; Lee, A.M.; Khanji, M.Y.; et al. Neuroticism Personality Traits Are Linked to Adverse Cardiovascular Phenotypes in the UK Biobank. Eur. Heart J.-Cardiovasc. Imaging 2023, 24, 1460–1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Chang, J.; Zhao, Y.; Tang, Y. Neuroticism Personality, Social Contact, and Dementia Risk: A Prospective Cohort Study. J. Affect. Disord. 2024, 358, 391–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajek, A.; Kretzler, B.; König, H.-H. Relationship between Personality Factors and Frailty. A Systematic Review. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2021, 97, 104508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, I.-C.; Lee, J.L.; Ketheeswaran, P.; Jones, C.M.; Revicki, D.A.; Wu, A.W. Does Personality Affect Health-Related Quality of Life? A Systematic Review. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0173806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roberts, B.W.; Luo, J.; Briley, D.A.; Chow, P.I.; Su, R.; Hill, P.L. A Systematic Review of Personality Trait Change through Intervention. Psychol. Bull. 2017, 143, 117–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donovan, S.M.; Abrahams, M.; Anthony, J.C.; Bao, Y.; Barragan, M.; Bermingham, K.M.; Blander, G.; Keck, A.-S.; Lee, B.Y.; Nieman, K.M.; et al. Personalized Nutrition: Perspectives on Challenges, Opportunities, and Guiding Principles for Data Use and Fusion. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2025, 65, 7151–7169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blizard, D.A.; Adams, N.; Boomsma, D.I. The Genetics of Neuroticism: Insights from the Maudsley Rat Model and Human Studies. Personal. Neurosci. 2023, 6, e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Der Walt, K.; Campbell, M.; Stein, D.J.; Dalvie, S. Systematic Review of Genome-Wide Association Studies of Anxiety Disorders and Neuroticism. World J. Biol. Psychiatry 2023, 24, 280–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aragam, N.; Wang, K.-S.; Anderson, J.L.; Liu, X. TMPRSS9 and GRIN2B Are Associated with Neuroticism: A Genome-Wide Association Study in a European Sample. J. Mol. Neurosci. 2013, 50, 250–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calboli, F.C.F.; Tozzi, F.; Galwey, N.W.; Antoniades, A.; Mooser, V.; Preisig, M.; Vollenweider, P.; Waterworth, D.; Waeber, G.; Johnson, M.R.; et al. A Genome-Wide Association Study of Neuroticism in a Population-Based Sample. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e11504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, K.L.; Livesley, W.J.; Vemon, P.A. Heritability of the Big Five Personality Dimensions and Their Facets: A Twin Study. J. Personal. 1996, 64, 577–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boomsma, D.I.; Helmer, Q.; Nieuwboer, H.A.; Hottenga, J.J.; De Moor, M.H.; Van Den Berg, S.M.; Davies, G.E.; Vink, J.M.; Schouten, M.J.; Dolan, C.V.; et al. An Extended Twin-Pedigree Study of Neuroticism in the Netherlands Twin Register. Behav. Genet. 2018, 48, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Assary, E.; Coleman, J.R.I.; Hemani, G.; Van De Weijer, M.P.; Howe, L.J.; Palviainen, T.; Grasby, K.L.; Ahlskog, R.; Nygaard, M.; Cheesman, R.; et al. Genetics of Monozygotic Twins Reveals the Impact of Environmental Sensitivity on Psychiatric and Neurodevelopmental Phenotypes. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2025, 9, 1683–1696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson, R.M.; Braithwaite, E.C.; Cadman, T.; Culpin, I.; Costantini, I.; Cordero, M.; Bornstein, M.H.; James, D.; Kwong, A.S.F.; Jones, H.; et al. The Proportion of Genetic Similarity for Liability for Neuroticism in Mother–Child and Mother–Father Dyads Is Associated with Reported Relationship Quality. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 29505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.-W.; Canli, T. “Nothing to See Here”: No Structural Brain Differences as a Function of the Big Five Personality Traits from a Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Personal. Neurosci. 2022, 5, e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Fang, P.; Qiu, G.; Wang, D.; Zhang, J.; Yang, Z.; Liu, H.; Shen, Q.; Liu, X. NDUFA10-Mediated ATP Reduction in Medial Prefrontal Cortex Exacerbates Burst Suppression in Aged Mice. CNS Neurosci. Ther. 2025, 31, e70453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.; Wen, Y.; Feng, C.; Xu, L.; Xian, Y.; Xie, H.; Huang, J.; Huang, Y.; Zhao, X.; Gao, X. Neuroglobin Protects Dopaminergic Neurons in a Parkinson’s Cell Model by Interacting with Mitochondrial Complex NDUFA10. Neuroscience 2024, 562, 43–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, P.; Hu, S.; Liu, X.; He, M.; Li, J.; Ma, T.; Huang, M.; Fang, Q.; Wang, Y. CAV3 Alleviates Diabetic Cardiomyopathy via Inhibiting NDUFA10-Mediated Mitochondrial Dysfunction. J. Transl. Med. 2024, 22, 390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Pang, X.; Guo, W.; Zhu, C.; Yu, L.; Song, X.; Wang, K.; Pang, C. An Exploration of the Coherent Effects between METTL3 and NDUFA10 on Alzheimer’s Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 10111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yahya, V.; Spagnolo, F.; Di Maggio, G.; Leopizzi, E.; De Marco, P.; Fortunato, F.; Comi, G.P.; Rini, A.; Monfrini, E.; Di Fonzo, A. Juvenile-Onset Dystonia with Spasticity in Leigh Syndrome Caused by a Novel NDUFA10 Variant. Park. Relat. Disord. 2022, 104, 85–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.-A.; Huang, K.-C. Epigenetic Profiling of Human Brain Differential DNA Methylation Networks in Schizophrenia. BMC Med. Genom. 2016, 9, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Y.; Li, L.; Zhang, X. Exploring Perspectives of Dscam for Cognitive Deficits: A Review of Multifunction for Regulating Neural Wiring in Homeostasis. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2025, 18, 1575348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajabi, A.H.; Zafarabadi, S.; Jazi, K.; Moghbel Baerz, M.; Bahrami, O.; Azarinoush, G.; Habibi, P.; Azami, N.; Paydar, S. Genetic Alterations in War-Related Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder: A Systematic Review. Bull. Emerge Trauma. 2025, 13, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neff, R.C.; Stangis, K.A.; Beniwal, U.; Hergenreder, T.; Ye, B.; Murphy, G.G. Cognitive Behavioral Phenotyping of DSCAM Heterozygosity as a Model for Autism Spectrum Disorder. Genes Brain Behav. 2024, 23, e70002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Caballero-Florán, R.N.; Hergenreder, T.; Yang, T.; Hull, J.M.; Pan, G.; Li, R.; Veling, M.W.; Isom, L.L.; Kwan, K.Y.; et al. DSCAM Gene Triplication Causes Excessive GABAergic Synapses in the Neocortex in Down Syndrome Mouse Models. PLoS Biol. 2023, 21, e3002078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández, K.; Godoy, L.; Newquist, G.; Kellermeyer, R.; Alavi, M.; Mathew, D.; Kidd, T. Dscam1 Overexpression Impairs the Function of the Gut Nervous System in Drosophila. Dev. Dyn. 2023, 252, 156–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WalyEldeen, A.A.; Sabet, S.; Anis, S.E.; Stein, T.; Ibrahim, A.M. FBLN2 Is Associated with Basal Cell Markers Krt14 and ITGB1 in Mouse Mammary Epithelial Cells and Has a Preferential Expression in Molecular Subtypes of Human Breast Cancer. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2024, 208, 673–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaeffer, J.; Tannahill, D.; Cioni, J.-M.; Rowlands, D.; Keynes, R. Identification of the Extracellular Matrix Protein Fibulin-2 as a Regulator of Spinal Nerve Organization. Dev. Biol. 2018, 442, 101–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niu, X.; Zhang, F.; Gu, W.; Zhang, B.; Chen, X. FBLN2 Is Associated with Goldenhar Syndrome and Is Essential for Cranial Neural Crest Cell Development. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2024, 1537, 113–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahlers-Dannen, K.E.; Yang, J.; Spicer, M.M.; Maity, B.; Stewart, A.; Koland, J.G.; Fisher, R.A. Protein Profiling of RGS6, a Pleiotropic Gene Implicated in Numerous Neuropsychiatric Disorders, Reveals Multi-Isoformic Expression and a Novel Brain-Specific Isoform. eNeuro 2022, 9, ENEURO.0379-21.2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahlers-Dannen, K.E.; Yang, J.; Spicer, M.M.; Fu, D.; DeVore, A.; Fisher, R.A. A Splice Acceptor Variant in RGS6 Associated with Intellectual Disability, Microcephaly, and Cataracts Disproportionately Promotes Expression of a Subset of RGS6 Isoforms. J. Hum. Genet. 2024, 69, 145–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sunday Willett, J.D.; Waqas, M.; Naumenko, S.; Mullin, K.; Hecker, J.; Bertram, L.; Lange, C.; Vlachos, I.; Hide, W.; Tanzi, R.E.; et al. Matching Heterogeneous Cohorts by Projected Principal Components Reveals Two Novel Alzheimer’s Disease-Associated Genes in the Hispanic Population. medRxiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, H.; Kittel-Schneider, S.; Gessner, A.; Domschke, K.; Neuner, M.; Jacob, C.P.; Buttenschon, H.N.; Boreatti-Hümmer, A.; Volkert, J.; Herterich, S.; et al. Cross-Disorder Analysis of Bipolar Risk Genes: Further Evidence of DGKH as a Risk Gene for Bipolar Disorder, but Also Unipolar Depression and Adult ADHD. Neuropsychopharmacology 2011, 36, 2076–2085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsumoto, Y.; Suzuki, A.; Shirata, T.; Takahashi, N.; Noto, K.; Goto, K.; Otani, K. Implication of the DGKH Genotype in Openness to Experience, a Premorbid Personality Trait of Bipolar Disorder. J. Affect. Disord. 2018, 238, 539–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Middeldorp, C.M.; De Moor, M.H.M.; McGrath, L.M.; Gordon, S.D.; Blackwood, D.H.; Costa, P.T.; Terracciano, A.; Krueger, R.F.; De Geus, E.J.C.; Nyholt, D.R.; et al. The Genetic Association between Personality and Major Depression or Bipolar Disorder. A Polygenic Score Analysis Using Genome-Wide Association Data. Transl. Psychiatry 2011, 1, e50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fekete, M.; Varga, P.; Ungvari, Z.; Fekete, J.T.; Buda, A.; Szappanos, Á.; Lehoczki, A.; Mózes, N.; Grosso, G.; Godos, J.; et al. The Role of the Mediterranean Diet in Reducing the Risk of Cognitive Impairement, Dementia, and Alzheimer’s Disease: A Meta-Analysis. GeroScience 2025, 47, 3111–3130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnstone, A.M.; Albanese, E.; Crabtree, D.R.; Dalile, B.; Grabrucker, S.; Gregory, J.M.; Grosso, G.; Holliday, A.; Hughes, C.; Itsiopoulos, C.; et al. Consensus Statement on Exploring the Nexus between Nutrition, Brain Health and Dementia Prevention. Nutr. Metab. 2025, 22, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Popiolek-Kalisz, J. The Role of Nutrition in Cardiovascular Protection-Personalized versus Universal Dietary Strategies. Trends Cardiovasc. Med. 2025, S1050173825001112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akerele, C.A.; Koralnik, L.R.; Lafont, E.; Gilman, C.; Walsh-Messinger, J.; Malaspina, D. Nutrition and Brain Health: Implications of Mediterranean Diet Elements for Psychiatric Disorders. Schizophr. Res. 2025, 281, 30–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, K.; Mitchell, B.D. A Guide to Understanding Mendelian Randomization Studies. Arthritis Care Res. 2024, 76, 1451–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davey Smith, G.; Paternoster, L.; Relton, C. When Will Mendelian Randomization Become Relevant for Clinical Practice and Public Health? JAMA 2017, 317, 589–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De La Vega, F.M.; Bustamante, C.D. Polygenic Risk Scores: A Biased Prediction? Genome Med. 2018, 10, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ndong Sima, C.A.A.; Step, K.; Swart, Y.; Schurz, H.; Uren, C.; Möller, M. Methodologies Underpinning Polygenic Risk Scores Estimation: A Comprehensive Overview. Hum. Genet. 2024, 143, 1265–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruan, Y.; Lin, Y.-F.; Feng, Y.-C.A.; Chen, C.-Y.; Lam, M.; Guo, Z.; Stanley Global Asia Initiatives; Ahn, Y.M.; Akiyama, K.; Arai, M.; et al. Improving Polygenic Prediction in Ancestrally Diverse Populations. Nat. Genet. 2022, 54, 573–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Calleja, J.; Biagini, S.A.; De Cid, R.; Calafell, F.; Bosch, E. Inferring Past Demography and Genetic Adaptation in Spain Using the GCAT Cohort. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 14225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Pan, Y.; Lu, S.; Kou, J.; Chen, X.; Zeng, W.; Luo, D.; Qiu, L.; Zhang, H.; Chen, D. Gut Microbiota-Mediated Targeting of EHMT2 in Individuals of European Ancestry: A Novel Therapeutic Approach for Alzheimer’s Disease. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2025, 107, 1575–1593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.E.; Cheng, Y.; Lim, J.; Jang, M.-A.; Forrest, E.N.; Kim, Y.; Donahue, M.; Jo, S.; Qiao, S.-N.; Lee, D.E.; et al. Mechanism of EHMT2-Mediated Genomic Imprinting Associated with Prader-Willi Syndrome. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 6125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Total | Men | Women | p 1 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 400) | (n = 169) | (n = 231) | ||

| Age (years) | 65.33 (4.71) | 64.27 (5.22) | 66.10 (4.14) | <0.001 |

| Body mass index (Kg/m2) | 32.14 (3.51) | 32.04 (3.33) | 32.21 (3.63) | 0.629 |

| Waist (cm) | 105.50 (9.90) | 110.81 (8.69) | 101.60 (8.88) | <0.001 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 141.50 (17.79) | 144.26 (18.21) | 139.49 (17.23) | 0.008 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 80.78 (9.90) | 82.54 (10.40) | 79.49 (9.33) | 0.002 |

| Fasting glucose (mg/dL) | 112.78 (26.59) | 114.72 (30.08) | 111.35 (23.68) | 0.211 |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dL) | 196.52 (38.02) | 187.40 (38.52) | 203.18 (36.31) | <0.001 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) | 142.31 (62.45) | 139.18 (56.35) | 144.60 (66.59) | 0.392 |

| Sleep duration WD | 6.75 (1.10) | 6.89 (1.07) | 6.64 (1.11) | 0.026 |

| Sleep duration FD | 7.10 (1.15) | 7.25 (1.11) | 6.99 (1.18) | 0.027 |

| Physical activity (MET.min/wk) | 1697 (1546) | 1984 (1830) | 1487 (1263) | 0.001 |

| MEDAS-17 | 8.01 (2.78) | 7.89 (2.87) | 8.10 (2.71) | 0.461 |

| MEDAS-14 | 8.14 (1.79) | 8.34 (2.00) | 7.98 (1.60) | 0.167 |

| Morning chronotype | 55.99 (7.85) | 57.17 (7.68) | 55.12 (7.88) | 0.011 |

| Depressive symptoms | 8.92 (6.19) | 6.95 (5.20) | 10.35 (6.46) | <0.001 |

| Neuroticism | 10.15 (5.31) | 8.68 (4.98) | 11.22 (5.31) | <0.001 |

| Psychoticism | 4.55 (2.72) | 4.25 (2.62) | 4.77 (2.77) | 0.057 |

| Extraversion | 12.22 (3.62) | 12.58 (3.51) | 11.95 (3.68) | 0.084 |

| Current smoker (%) | 10.3 | 15.4 | 6.5 | <0.001 |

| Diabetes (%) | 38.8 | 39.1 | 38.5 | 0.915 |

| Primary education (%) | 62.8 | 49.1 | 72.7 | <0.001 |

| University education (%) | 17.0 | 21.3 | 13.9 | <0.001 |

| Personality Trait | Beta 1 (SE) | p 1 | Beta 2 (SE) | p 2 | Beta 3 (SE) | p 3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neuroticism | −0.090 (0.026) | 0.001 | −0.097 (0.027) | <0.001 | −0.089 (0.027) | 0.001 |

| Psychoticism | −0.106 (0.051) | 0.038 | −0.103 (0.051) | 0.047 | −0.065 (0.051) | 0.222 |

| Extraversion | 0.033 (0.038) | 0.391 | 0.040 (0.039) | 0.300 | 0.044 (0.038) | 0.247 |

| Combined factor | −0.498 (0.138) | <0.001 | −0.529 (0.142) | <0.001 | −0.429 (0.143) | 0.003 |

| Personality Trait | OR 1 (95% CI) | p 1 | OR 2 (95% CI) | p 2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neuroticism | 1.30 (1.05–1.60) | 0.015 | 1.27 (1.02–1.60) | 0.031 |

| Psychoticism | 1.33 (1.07–1.64) | 0.009 | 1.23 (0.99–1.54) | 0.064 |

| Extraversion | 0.86 (0.70–1.06) | 0.166 | 0.86 (0.70–1.07) | 0.175 |

| Combined factor | 1.44 (1.16–1.79) | 0.001 | 1.36 (1.09–1.70) | 0.007 |

| SNP | CHR | BP | A1 | Beta | p | Gene Symbol | MAF 1 | MAF 2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rs10181407 | 2 | 240857988 | A | −2.392 | 2.70 × 10−6 | NDUFA10 | 0.154 | 0.238 |

| rs10933578 | 2 | 240858334 | A | −2.368 | 3.37 × 10−6 | NDUFA10 | 0.155 | 0.238 |

| rs4596126 | 3 | 13659897 | C | 2.087 | 9.00 × 10−6 | FBLN2, SNORA93 | 0.202 | 0.394 |

| rs11910405 | 21 | 42077795 | C | −1.97 | 9.03 × 10−6 | DSCAM | 0.188 | 0.216 |

| rs3792089 | 2 | 240947066 | A | −2.338 | 1.14 × 10−5 | NDUFA10 | 0.150 | 0.072 |

| rs1248033 | 12 | 114881294 | A | −1.642 | 1.42 × 10−5 | intergenic | 0.397 | 0.120 |

| rs967476 | 2 | 240920291 | A | −2.300 | 1.43 × 10−5 | NDUFA10 | 0.153 | 0.101 |

| rs2283416 | 14 | 72607322 | G | 1.837 | 1.66 × 10−5 | RGS6 | 0.243 | 0.298 |

| rs10753107 | 1 | 171398925 | G | 2.076 | 1.83 × 10−5 | intergenic | 0.178 | 0.139 |

| rs2840467 | 8 | 5798398 | G | 2.899 | 1.87 × 10−5 | intergenic | 0.082 | 0.135 |

| rs6682065 | 1 | 171397553 | A | 2.075 | 1.91 × 10−5 | intergenic | 0.182 | 0.139 |

| rs7958517 | 12 | 99837070 | G | 1.745 | 2.03 × 10−5 | ANKS1B | 0.327 | 0.459 |

| rs7754801 | 6 | 96301487 | A | −1.683 | 2.09 × 10−5 | intergenic | 0.301 | 0.163 |

| rs6426154 | 1 | 224909092 | G | 1.660 | 2.35 × 10−5 | CNIH3 | 0.351 | 0.466 |

| rs13200002 | 6 | 168577460 | A | 2.149 | 2.40 × 10−5 | intergenic | 0.147 | 0.198 |

| rs2183578 | 21 | 42078727 | A | −1.705 | 2.68 × 10−5 | DSCAM | 0.265 | 0.274 |

| rs7303478 | 12 | 99827565 | C | 1.721 | 3.00 × 10−5 | ANKS1B | 0.321 | 0.440 |

| rs4808814 | 19 | 18637610 | A | 1.604 | 3.09 × 10−5 | intergenic | 0.325 | 0.452 |

| rs2703312 | 8 | 5818128 | A | 2.805 | 3.15 × 10−5 | intergenic | 0.083 | 0.195 |

| rs33510 | 3 | 42391480 | G | 1.814 | 3.41 × 10−5 | intergenic | 0.244 | 0.245 |

| rs9566946 | 13 | 42820124 | A | 1.689 | 3.46 × 10−5 | DGKH | 0.282 | 0.293 |

| rs2799665 | 6 | 96309043 | A | −1.616 | 3.52 × 10−5 | intergenic | 0.326 | 0.440 |

| rs1483373 | 8 | 90186443 | A | −3.750 | 3.60 × 10−5 | intergenic | 0.049 | 0.261 |

| rs9323788 | 14 | 86850171 | G | 1.612 | 3.63 × 10−5 | intergenic | 0.296 | 0.281 |

| rs10804402 | 2 | 240957801 | A | −2.171 | 3.66 × 10−5 | NDUFA10 | 0.159 | 0.161 |

| rs28408009 | 4 | 39566499 | G | 1.835 | 3.85 × 10−5 | SMIM14 | 0.214 | 0.411 |

| rs17122386 | 14 | 86916425 | G | 1.621 | 3.92 × 10−5 | Intergenic | 0.285 | 0.238 |

| rs10019815 | 4 | 39559690 | A | 1.851 | 4.02 × 10−5 | SMIM14 | 0.216 | 0.389 |

| rs7842444 | 8 | 90193247 | G | −3.88 | 4.16 × 10−5 | intergenic | 0.045 | 0.264 |

| rs2189599 | 5 | 136409585 | A | 1.929 | 4.33 × 10−5 | SPOCK1 | 0.192 | 0.370 |

| rs6517607 | 21 | 42067941 | G | −1.799 | 4.44 × 10−5 | DSCAM | 0.199 | 0.224 |

| rs28688395 | 7 | 31812761 | G | 1.772 | 4.64 × 10−5 | PDE1C | 0.251 | 0.416 |

| SNP | CHR | BP | A1 | Valencia MAF | Valencia Beta | p 1 | Genes | Meta EAF | Meta Beta | p 2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rs12407512 | 1 | 217344002 | C | 0.132 | −1.122 | 3.67 × 10−2 | intergenic | 0.840 | 0.016 | 3.12 × 10−8 |

| rs2243873 | 6 | 31863433 | C | 0.352 | −0.794 | 4.49 × 10−2 | EHMT2 | 0.575 | 0.012 | 3.29 × 10−8 |

| rs4585149 | 3 | 157493952 | A | 0.209 | −0.864 | 4.83 × 10−2 | intergenic | 0.177 | −0.017 | 1.00 × 10−8 |

| rs1187257 | 18 | 35288227 | G | 0.243 | 0.805 | 6.03 × 10−2 | intergenic | 0.715 | −0.014 | 2.04 × 10−8 |

| rs7025144 | 9 | 120496387 | A | 0.255 | 0.792 | 6.29 × 10−2 | intergenic | 0.272 | 0.018 | 5.20 × 10−13 |

| Low AMD | High AMD | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SNP | CHR | Genes | MAF | p-GxD | Beta 1 | SE1 | Beta 2 | SE2 |

| rs12407512 | 1 | intergenic | 0.132 | 1.30 × 10−2 | 0.111 | 0.749 | −2.613 | 0.801 |

| rs3741475 | 12 | NOS1 | 0.260 | 3.48 × 10−2 | 0.498 | 0.572 | −1.360 | 0.669 |

| rs2155281 | 11 | NCAM1 | 0.352 | 3.81 × 10−2 | 0.699 | 0.510 | −0.966 | 0.620 |

| rs3793577 | 9 | ELAVL2 | 0.499 | 1.50 × 10−1 | 0.063 | 0.478 | −1.036 | 0.594 |

| rs17432675 | 1 | LMOD1 | 0.397 | 2.31 × 10−1 | 0.610 | 0.481 | −0.341 | 0.633 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sorlí, J.V.; Ortega-Azorín, C.; Coltell, O.; Fernández-Carrión, R.; Asensio, E.M.; Portolés, O.; Perez-Fidalgo, A.; Ramirez-Sabio, J.B.; Guillem-Saiz, J.; Costa, J.A.; et al. Linking Personality Traits to Mediterranean Diet Adherence and Exploring Gene–Diet Interactions in Neuroticism. Nutrients 2025, 17, 3791. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17233791

Sorlí JV, Ortega-Azorín C, Coltell O, Fernández-Carrión R, Asensio EM, Portolés O, Perez-Fidalgo A, Ramirez-Sabio JB, Guillem-Saiz J, Costa JA, et al. Linking Personality Traits to Mediterranean Diet Adherence and Exploring Gene–Diet Interactions in Neuroticism. Nutrients. 2025; 17(23):3791. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17233791

Chicago/Turabian StyleSorlí, José V., Carolina Ortega-Azorín, Oscar Coltell, Rebeca Fernández-Carrión, Eva M. Asensio, Olga Portolés, Alejandro Perez-Fidalgo, Judith B. Ramirez-Sabio, Javier Guillem-Saiz, José A. Costa, and et al. 2025. "Linking Personality Traits to Mediterranean Diet Adherence and Exploring Gene–Diet Interactions in Neuroticism" Nutrients 17, no. 23: 3791. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17233791

APA StyleSorlí, J. V., Ortega-Azorín, C., Coltell, O., Fernández-Carrión, R., Asensio, E. M., Portolés, O., Perez-Fidalgo, A., Ramirez-Sabio, J. B., Guillem-Saiz, J., Costa, J. A., Gimenez-Alba, I. M., Barragán, R., Ordovas, J. M., & Corella, D. (2025). Linking Personality Traits to Mediterranean Diet Adherence and Exploring Gene–Diet Interactions in Neuroticism. Nutrients, 17(23), 3791. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17233791