Can Beetroot (Beta vulgaris) Support Brain Health? A Perspective Review on Alzheimer’s Disease

Abstract

1. Introduction

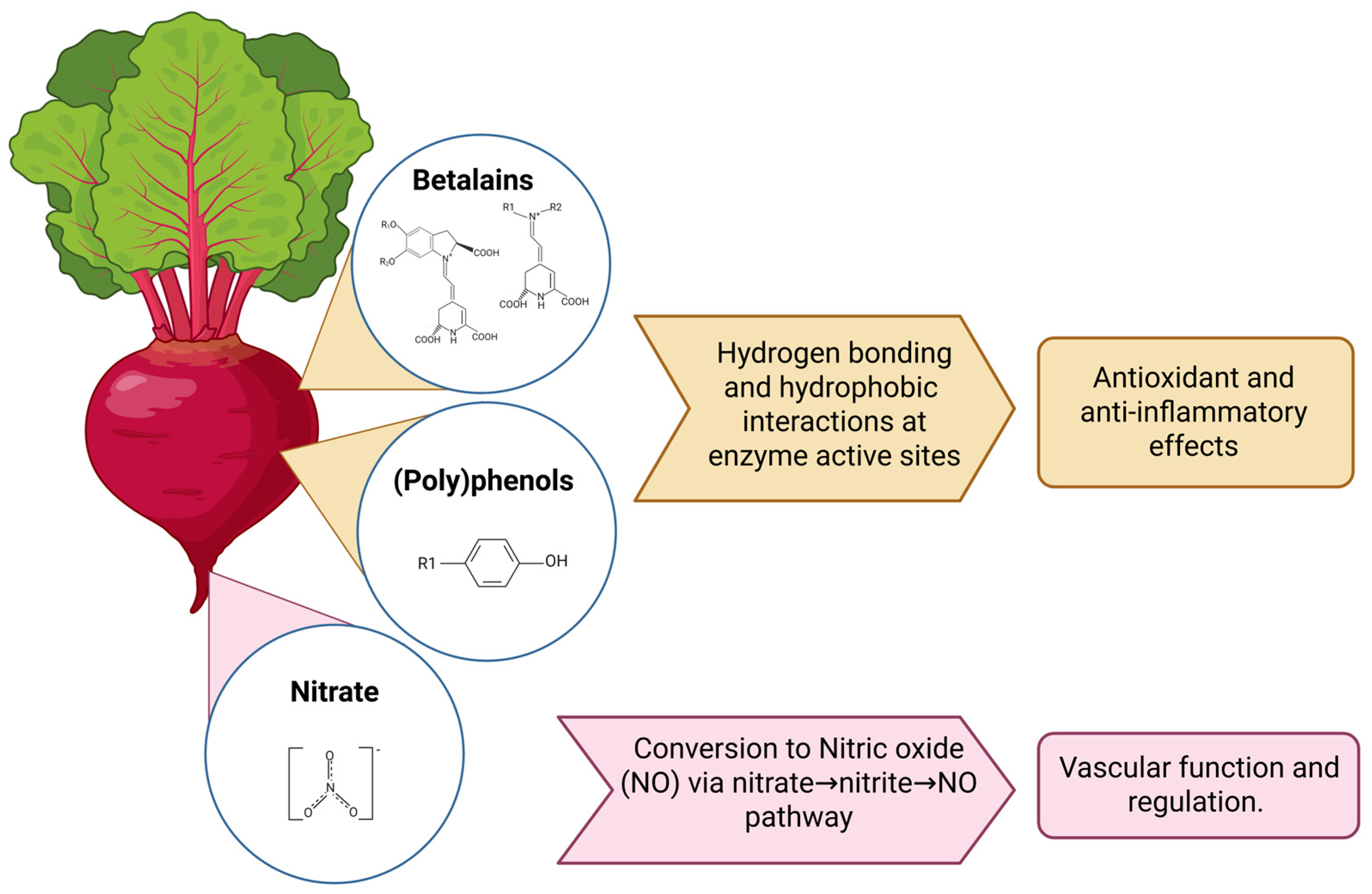

2. Beetroot Neuroprotective Mechanisms

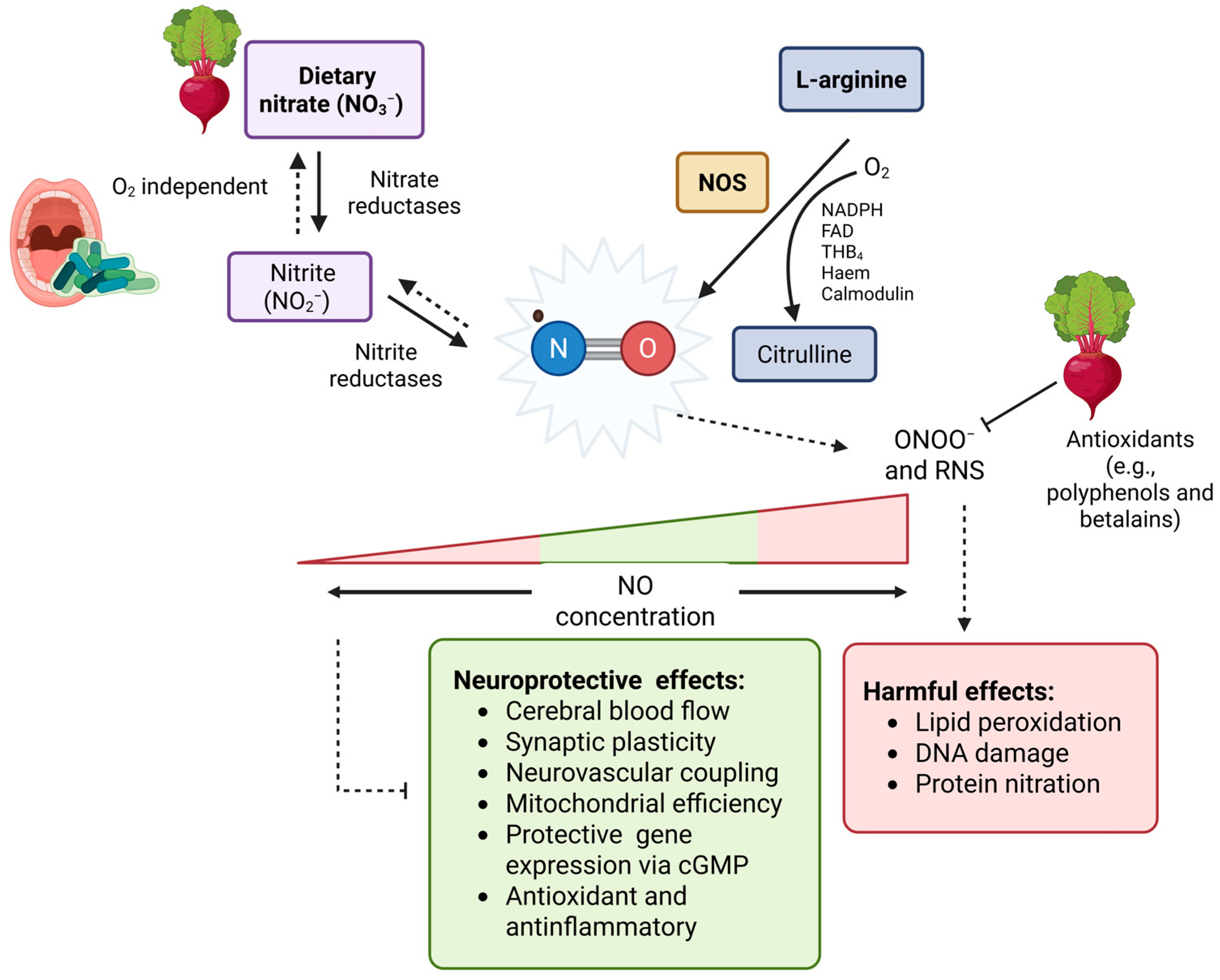

2.1. Nitrate and Brain Health

2.2. Betalains and Polyphenols in Brain Health

2.3. Beetroot and the Microbiota–Brain Axis

3. Beetroot and Brain Health: Epidemiological Evidence and Clinical Insights

4. Current Gaps and Limitations

5. Future Research Directions

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Aβ | Amyloid-β |

| ACC | Anterior cingulate cortex |

| AChE | Acetylcholinesterase |

| AD | Alzheimer’s disease |

| APOE | Apolipoprotein E |

| BH4 | Tetrahydrobiopterin |

| CBF | Cerebral blood flow |

| cGMP | Cyclic guanosine monophosphate |

| DLPFC | Dorsolateral prefrontal cortex |

| eNOS | Endothelial nitric oxide synthases |

| FAD | Flavin adenine dinucleotide |

| IL-6 | Interleukin-6 |

| iNOS | Inducible nitric oxide synthases |

| LPS | Lipopolysaccharide |

| NADPH | Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate |

| NHANES | National health and nutrition examination survey |

| nNOS | Neuronal nitric oxide synthases |

| NO | Nitric oxide |

| PC12 | Rat adrenal pheochromocytoma cell line |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| RNS | Reactive nitrogen species |

| SCFA | Short-chain fatty acid |

| TNF-α | Tumour necrosis factor-alpha |

References

- Skaria, A.P. The economic and societal burden of Alzheimer disease: Managed care considerations. Am. J. Manag. Care 2022, 28, S188–S196. [Google Scholar]

- Nichols, E.; Steinmetz, J.D.; Vollset, S.E.; Fukutaki, K.; Chalek, J.; Abd-Allah, F.; Abdoli, A.; Abualhasan, A.; Abu-Gharbieh, E.; Akram, T.T.; et al. Estimation of the global prevalence of dementia in 2019 and forecasted prevalence in 2050: An analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Public Health 2022, 7, e105–e125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celis-Morales, C.; Livingstone, K.M.; Marsaux, C.F.; Macready, A.L.; Fallaize, R.; O’Donovan, C.B.; Woolhead, C.; Forster, H.; Walsh, M.C.; Navas-Carretero, S.; et al. Effect of personalized nutrition on health-related behaviour change: Evidence from the Food4Me European randomized controlled trial. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2017, 46, 578–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sims, J.R.; Zimmer, J.A.; Evans, C.D.; Lu, M.; Ardayfio, P.; Sparks, J.; Wessels, A.M.; Shcherbinin, S.; Wang, H.; Monkul Nery, E.S.; et al. Donanemab in Early Symptomatic Alzheimer Disease: The TRAILBLAZER-ALZ 2 Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2023, 330, 512–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dyck, C.H.; Swanson, C.J.; Aisen, P.; Bateman, R.J.; Chen, C.; Gee, M.; Kanekiyo, M.; Li, D.; Reyderman, L.; Cohen, S. Lecanemab in early Alzheimer’s disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2023, 388, 9–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.V.; Mital, S.; Knopman, D.S.; Alexander, G.C. Cost-Effectiveness of Lecanemab for Individuals with Early-Stage Alzheimer Disease. Neurology 2024, 102, e209218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verma, A.; Kumar Waiker, D.; Bhardwaj, B.; Saraf, P.; Shrivastava, S.K. The molecular mechanism, targets, and novel molecules in the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. Bioorg. Chem. 2022, 119, 105562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bai, R.; Guo, J.; Ye, X.-Y.; Xie, Y.; Xie, T. Oxidative stress: The core pathogenesis and mechanism of Alzheimer’s disease. Ageing Res. Rev. 2022, 77, 101619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perluigi, M.; Di Domenico, F.; Butterfield, D.A. Oxidative damage in neurodegeneration: Roles in the pathogenesis and progression of Alzheimer disease. Physiol. Rev. 2024, 104, 103–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ionescu-Tucker, A.; Cotman, C.W. Emerging roles of oxidative stress in brain aging and Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol. Aging 2021, 107, 86–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alkhalifa, A.E.; Alkhalifa, O.; Durdanovic, I.; Ibrahim, D.R.; Maragkou, S. Oxidative Stress and Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Alzheimer’s Disease: Insights into Pathophysiology and Treatment. J. Dement. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2025, 2, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klohs, J. An integrated view on vascular dysfunction in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurodegener. Dis. 2019, 19, 109–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maitre, Y.; Mahalli, R.; Micheneau, P.; Delpierre, A.; Amador, G.; Denis, F. Evidence and therapeutic perspectives in the relationship between the oral microbiome and Alzheimer’s disease: A systematic review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 11157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Gao, J.; Zhu, M.; Liu, K.; Zhang, H.-L. Gut microbiota and dysbiosis in Alzheimer’s disease: Implications for pathogenesis and treatment. Mol. Neurobiol. 2020, 57, 5026–5043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lloret, A.; Esteve, D.; Monllor, P.; Cervera-Ferri, A.; Lloret, A. The Effectiveness of Vitamin E Treatment in Alzheimer’s Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clifford, T.; Howatson, G.; West, D.J.; Stevenson, E.J. The Potential Benefits of Red Beetroot Supplementation in Health and Disease. Nutrients 2015, 7, 2801–2822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sentkowska, A.; Pyrzyńska, K. Old-fashioned, but still a superfood—Red beets as a rich source of bioactive compounds. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 7445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiruvengadam, M.; Chung, I.-M.; Samynathan, R.; Chandar, S.R.H.; Venkidasamy, B.; Sarkar, T.; Rebezov, M.; Gorelik, O.; Shariati, M.A.; Simal-Gandara, J. A comprehensive review of beetroot (Beta vulgaris L.) bioactive components in the food and pharmaceutical industries. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2024, 64, 708–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siervo, M.; Babateen, A.; Alharbi, M.; Stephan, B.; Shannon, O. Dietary nitrate and brain health. Too much ado about nothing or a solution for dementia prevention? Br. J. Nutr. 2022, 128, 1130–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siervo, M.; Scialò, F.; Shannon, O.M.; Stephan, B.C.M.; Ashor, A.W. Does dietary nitrate say NO to cardiovascular ageing? Current evidence and implications for research. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2018, 77, 112–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shannon, O.M.; Gregory, S.; Siervo, M. Dietary nitrate, aging and brain health: The latest evidence. Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care 2022, 25, 393–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajendra, A.; Bondonno, N.P.; Rainey-Smith, S.R.; Gardener, S.L.; Hodgson, J.M.; Bondonno, C.P. Potential role of dietary nitrate in relation to cardiovascular and cerebrovascular health, cognition, cognitive decline and dementia: A review. Food Funct. 2022, 13, 12572–12589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hord, N.G.; Tang, Y.; Bryan, N.S. Food sources of nitrates and nitrites: The physiologic context for potential health benefits. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2009, 90, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lundberg, J.O.; Gladwin, M.T.; Ahluwalia, A.; Benjamin, N.; Bryan, N.S.; Butler, A.; Cabrales, P.; Fago, A.; Feelisch, M.; Ford, P.C.; et al. Nitrate and nitrite in biology, nutrition and therapeutics. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2009, 5, 865–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dos Santos Baião, D.; Vieira Teixeira da Silva, D.; Margaret Flosi Paschoalin, V. A Narrative Review on Dietary Strategies to Provide Nitric Oxide as a Non-Drug Cardiovascular Disease Therapy: Beetroot Formulations-A Smart Nutritional Intervention. Foods 2021, 10, 859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celik, B.; Muriuki, E.; Kuhnle, G.G.C.; Spencer, J.P.E.; Mills, C.E. The Impact of Inorganic Nitrate on Endothelial Function: A Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Trials and Meta-analysis. Nutr. Rev. 2025, nuaf132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirmiran, P.; Houshialsadat, Z.; Gaeini, Z.; Bahadoran, Z.; Azizi, F. Functional properties of beetroot (Beta vulgaris) in management of cardio-metabolic diseases. Nutr. Metab. 2020, 17, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayes, E.; Alhulaefi, S.; Siervo, M.; Whyte, E.; Kimble, R.; Matu, J.; Griffiths, A.; Sim, M.; Burleigh, M.; Easton, C. Inter-individual differences in the blood pressure lowering effects of dietary nitrate: A randomised double-blind placebo-controlled replicate crossover trial. Eur. J. Nutr. 2025, 64, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de la Torre, J.C.; Stefano, G.B. Evidence that Alzheimer’s disease is a microvascular disorder: The role of constitutive nitric oxide. Brain Res. Brain Res. Rev. 2000, 34, 119–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de la Monte, S.M. Type 3 diabetes is sporadic Alzheimer׳s disease: Mini-review. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2014, 24, 1954–1960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azargoonjahromi, A. Dual role of nitric oxide in Alzheimer’s disease. Nitric Oxide 2023, 134–135, 23–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benarroch, E.E. Nitric oxide. Neurology 2011, 77, 1568–1576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lundberg, J.O.; Weitzberg, E.; Gladwin, M.T. The nitrate–nitrite–nitric oxide pathway in physiology and therapeutics. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2008, 7, 156–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Förstermann, U.; Sessa, W.C. Nitric oxide synthases: Regulation and function. Eur. Heart J. 2012, 33, 829–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Lu, D.; Wang, X.; Wang, Z.; Li, W.; Chen, G. The effects of nitric oxide in Alzheimer’s disease. Med. Gas Res. 2024, 14, 186–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mak, S.; Liu, Z.; Wu, L.; Guo, B.; Luo, F.; Liu, Z.; Hu, S.; Wang, J.; Cui, G.; Sun, Y.; et al. Pharmacological Characterizations of anti-Dementia Memantine Nitrate via Neuroprotection and Vasodilation in Vitro and in Vivo. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2020, 11, 314–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thatcher, G.R.; Bennett, B.M.; Dringenberg, H.C.; Reynolds, J.N. Novel nitrates as NO mimetics directed at Alzheimer’s disease. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2005, 6, S75–S84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, G.; Zhang, K.; Sun, M.; Xie, N.; Wu, L.; Zhang, G.; Guo, B.; Huang, C.; Man Hoi, M.P.; Zhang, G.; et al. Multi-functional memantine nitrate attenuated cognitive impairment in models of vascular dementia and Alzheimer’s disease through neuroprotection and increased cerebral blood flow. Neuropharmacology 2025, 272, 110410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dubey, H.; Dubey, A.; Gulati, K.; Ray, A. S-nitrosoglutathione modulates HDAC2 and BDNF levels in the brain and improves cognitive deficits in experimental model of Alzheimer’s disease in rats. Int. J. Neurosci. 2024, 134, 777–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubey, H.; Ray, A.; Dubey, A.; Gulati, K. S-Nitrosoglutathione Attenuates Oxidative Stress and Improves Retention Memory Dysfunctions in Intra-Cerebroventricular-Streptozotocin Rat Model of Sporadic Alzheimer’s Disease via Activation of BDNF and Nuclear Factor Erythroid 2-Related Factor-2 Antioxidant Signaling Pathway. Neuropsychobiology 2024, 83, 101–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rifkind, J.M.; Nagababu, E.; Barbiro-Michaely, E.; Ramasamy, S.; Pluta, R.M.; Mayevsky, A. Nitrite infusion increases cerebral blood flow and decreases mean arterial blood pressure in rats: A role for red cell NO. Nitric Oxide 2007, 16, 448–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christie, I.N.; Theparambil, S.M.; Braga, A.; Doronin, M.; Hosford, P.S.; Brazhe, A.; Mascarenhas, A.; Nizari, S.; Hadjihambi, A.; Wells, J.A.; et al. Astrocytes produce nitric oxide via nitrite reduction in mitochondria to regulate cerebral blood flow during brain hypoxia. Cell Rep. 2023, 42, 113514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohanakumar, K.P.; Thomas, B.; Sharma, S.M.; Muralikrishnan, D.; Chowdhury, R.; Chiueh, C.C. Nitric oxide: An antioxidant and neuroprotector. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2002, 962, 389–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olasehinde, T.A.; Oyeleye, S.I.; Ibeji, C.U.; Oboh, G. Beetroot supplemented diet exhibit anti-amnesic effect via modulation of cholinesterases, purinergic enzymes, monoamine oxidase and attenuation of redox imbalance in the brain of scopolamine treated male rats. Nutr. Neurosci. 2022, 25, 1011–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matysek, M.; Kowalczuk-Vasilev, E.; Szalak, R.; Baranowska-Wójcik, E.; Arciszewski, M.B.; Szwajgier, D. Can Bioactive Compounds in Beetroot/Carrot Juice Have a Neuroprotective Effect? Morphological Studies of Neurons Immunoreactive to Calretinin of the Rat Hippocampus after Exposure to Cadmium. Foods 2022, 11, 2794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinson, J.A.; Hao, Y.; Su, X.; Zubik, L. Phenol Antioxidant Quantity and Quality in Foods: Vegetables. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1998, 46, 3630–3634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tayarani-Najaran, Z.; Dehghanpour Farashah, M.; Emami, S.A.; Ramazani, E.; Shahraki, N.; Hadipour, E. Protective effects of betanin, a novel acetylcholinesterase inhibitor, against H2O2-induced apoptosis in PC12 cells. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2024, 51, 986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmadi, H.; Nayeri, Z.; Minuchehr, Z.; Sabouni, F.; Mohammadi, M. Betanin purification from red beetroots and evaluation of its anti-oxidant and anti-inflammatory activity on LPS-activated microglial cells. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0233088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shunan, D.; Yu, M.; Guan, H.; Zhou, Y. Neuroprotective effect of Betalain against AlCl3-induced Alzheimer’s disease in Sprague Dawley Rats via putative modulation of oxidative stress and nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) signaling pathway. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2021, 137, 111369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salimi, A.; Sabur, M.; Dadkhah, M.; Shabani, M. Inhibition of scopolamine-induced memory and mitochondrial impairment by betanin. J. Biochem. Mol. Toxicol. 2022, 36, e23076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojo, O.A.; Gyebi, G.A.; Ezenabor, E.H.; Iyobhebhe, M.; Emmanuel, D.A.; Adelowo, O.A.; Olujinmi, F.E.; Ogunwale, T.E.; Babatunde, D.E.; Ogunlakin, A.D.; et al. Exploring beetroot (Beta vulgaris L.) for diabetes mellitus and Alzheimer’s disease dual therapy: In vitro and computational studies. RSC Adv. 2024, 14, 19362–19380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, S.; Ali Ashfaq, U.; Sufyan, M.; Shahid, I.; Ijaz, B.; Hussain, M. The Insight of In Silico and In Vitro evaluation of Beta vulgaris phytochemicals against Alzheimer’s disease targeting acetylcholinesterase. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0264074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adil, N.A.; Omo-Erigbe, C.; Yadav, H.; Jain, S. The oral–gut microbiome–brain axis in cognition. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Narengaowa; Kong, W.; Lan, F.; Awan, U.F.; Qing, H.; Ni, J. The oral-gut-brain AXIS: The influence of microbes in Alzheimer’s disease. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2021, 15, 633735. [Google Scholar]

- de Oliveira, S.P.A.; do Nascimento, H.M.A.; Sampaio, K.B.; de Souza, E.L. A review on bioactive compounds of beet (Beta vulgaris L. subsp. vulgaris) with special emphasis on their beneficial effects on gut microbiota and gastrointestinal health. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2021, 61, 2022–2033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Do, T.; Marshall, L.J.; Boesch, C. Effect of two-week red beetroot juice consumption on modulation of gut microbiota in healthy human volunteers—A pilot study. Food Chem. 2023, 406, 134989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fejes, R.; Séneca, J.; Pjevac, P.; Lutnik, M.; Weisshaar, S.; Pilat, N.; Steiner, R.; Wagner, K.H.; Woodman, R.J.; Bondonno, C.P. Increased Nitrate Intake from Beetroot Juice Over 4 Weeks Changes the Composition of the Oral, But Not the Intestinal Microbiome. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2025, 69, e70156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burleigh, M.; Liddle, L.; Muggeridge, D.J.; Monaghan, C.; Sculthorpe, N.; Butcher, J.; Henriquez, F.; Easton, C. Dietary nitrate supplementation alters the oral microbiome but does not improve the vascular responses to an acute nitrate dose. Nitric Oxide 2019, 89, 54–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doel, J.J.; Benjamin, N.; Hector, M.P.; Rogers, M.; Allaker, R.P. Evaluation of bacterial nitrate reduction in the human oral cavity. Eur. J. Oral Sci. 2005, 113, 14–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vanhatalo, A.; L’Heureux, J.E.; Kelly, J.; Blackwell, J.R.; Wylie, L.J.; Fulford, J.; Winyard, P.G.; Williams, D.W.; van der Giezen, M.; Jones, A.M. Network analysis of nitrate-sensitive oral microbiome reveals interactions with cognitive function and cardiovascular health across dietary interventions. Redox Biol. 2021, 41, 101933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsushita, K.; Yamada-Furukawa, M.; Kurosawa, M.; Shikama, Y. Periodontal Disease and Periodontal Disease-Related Bacteria Involved in the Pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s Disease. J. Inflamm. Res. 2020, 13, 275–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Venturelli, M.; Pedrinolla, A.; Boscolo Galazzo, I.; Fonte, C.; Smania, N.; Tamburin, S.; Muti, E.; Crispoltoni, L.; Stabile, A.; Pistilli, A.; et al. Impact of Nitric Oxide Bioavailability on the Progressive Cerebral and Peripheral Circulatory Impairments During Aging and Alzheimer’s Disease. Front Physiol 2018, 9, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Adekolurejo, O.O.; Wang, B.; McDermott, K.; Do, T.; Marshall, L.J.; Boesch, C. Bioavailability and excretion profile of betacyanins–Variability and correlations between different excretion routes. Food Chem. 2024, 437, 137663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H.; Zhang, D.; Wu, J.; Liu, J.; Zhou, Y.; Tan, Y.; Feng, W.; Peng, C. Interactions between gut microbiota and polyphenols: A mechanistic and metabolomic review. Phytomedicine 2023, 119, 154979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capper, T.E.; Houghton, D.; Stewart, C.J.; Blain, A.P.; McMahon, N.; Siervo, M.; West, D.J.; Stevenson, E.J. Whole beetroot consumption reduces systolic blood pressure and modulates diversity and composition of the gut microbiota in older participants. NFS J. 2020, 21, 28–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhammad, J.A.; Ngouongo, Y.J.W.; Ramirez, S.; Kautz, T.F.; Satizabal, C.L.; Himali, J.J.; Seshadri, S.; Fongang, B. Poor cognition is associated with increased abundance of Alistipes and decreased abundance of Clostridium genera in the gut. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2023, 19, e076520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogt, N.M.; Kerby, R.L.; Dill-McFarland, K.A.; Harding, S.J.; Merluzzi, A.P.; Johnson, S.C.; Carlsson, C.M.; Asthana, S.; Zetterberg, H.; Blennow, K.; et al. Gut microbiome alterations in Alzheimer’s disease. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 13537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, X.H.; Xie, R.Y.; Liu, X.L.; Chen, S.D.; Tang, H.D. Mechanisms of Short-Chain Fatty Acids Derived from Gut Microbiota in Alzheimer’s Disease. Aging Dis. 2022, 13, 1252–1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, M.C.; Wang, Y.; Barnes, L.L.; Bennett, D.A.; Dawson-Hughes, B.; Booth, S.L. Nutrients and bioactives in green leafy vegetables and cognitive decline: Prospective study. Neurology 2018, 90, e214–e222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, L.C.R.; Shannon, O.M.; Mazidi, M.; Babateen, A.M.; Ashor, A.W.; Stephan, B.C.M.; Siervo, M. Relationship between urinary nitrate concentrations and cognitive function in older adults: Findings from the NHANES survey. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2021, 72, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajendra, A.; Bondonno, N.P.; Zhong, L.; Radavelli-Bagatini, S.; Murray, K.; Rainey-Smith, S.R.; Gardener, S.L.; Blekkenhorst, L.C.; Magliano, D.J.; Shaw, J.E.; et al. Plant but not animal sourced nitrate intake is associated with lower dementia-related mortality in the Australian Diabetes, Obesity, and Lifestyle Study. Front. Nutr. 2024, 11, 1327042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowles, E.F.; Burleigh, M.; Mira, A.; Van Breda, S.G.J.; Weitzberg, E.; Rosier, B.T. Nitrate: “the source makes the poison”. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2025, 65, 4676–4702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajendra, A.; Bondonno, N.P.; Murray, K.; Zhong, L.; Rainey-Smith, S.R.; Gardener, S.L.; Blekkenhorst, L.C.; Ames, D.; Maruff, P.; Martins, R.N.; et al. Habitual dietary nitrate intake and cognition in the Australian Imaging, Biomarkers and Lifestyle Study of ageing: A prospective cohort study. Clin. Nutr. 2023, 42, 1251–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajendra, A.; Bondonno, N.P.; Murray, K.; Zhong, L.; Rainey-Smith, S.R.; Gardener, S.L.; Blekkenhorst, L.C.; Doré, V.; Villemagne, V.L.; Laws, S.M.; et al. Baseline habitual dietary nitrate intake and Alzheimer’s Disease related neuroimaging biomarkers in the Australian Imaging, Biomarkers and Lifestyle study of ageing. J. Prev. Alzheimers Dis. 2025, 12, 100161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clifford, T.; Babateen, A.; Shannon, O.M.; Capper, T.; Ashor, A.; Stephan, B.; Robinson, L.; O’Hara, J.P.; Mathers, J.C.; Stevenson, E.; et al. Effects of Inorganic Nitrate and Nitrite Consumption on Cognitive Function and Cerebral Blood Flow: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomised Clinical Trials. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2018, 59, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Presley, T.D.; Morgan, A.R.; Bechtold, E.; Clodfelter, W.; Dove, R.W.; Jennings, J.M.; Kraft, R.A.; King, S.B.; Laurienti, P.J.; Rejeski, W.J.; et al. Acute effect of a high nitrate diet on brain perfusion in older adults. Nitric Oxide 2011, 24, 34–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, H.R.; Pan, P.L.; Sheng, L.Q.; Dai, Z.Y.; Wang, G.D.; Luo, R.; Chen, J.H.; Xiao, P.R.; Zhong, J.G.; Shi, H.C. Aberrant pattern of regional cerebral blood flow in Alzheimer’s disease: A voxel-wise meta-analysis of arterial spin labeling MR imaging studies. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 93196–93208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.L.; O’Donnell, T.; Lanford, J.; Croft, K.; Watson, E.; Smyth, D.; Koch, H.; Wong, L.K.; Tzeng, Y.C. Dietary nitrate reduces blood pressure and cerebral artery velocity fluctuations and improves cerebral autoregulation in transient ischemic attack patients. J. Appl. Physiol. 2020, 129, 547–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fejes, R.; Pilat, N.; Lutnik, M.; Weisshaar, S.; Weijler, A.M.; Krüger, K.; Draxler, A.; Bragagna, L.; Peake, J.M.; Woodman, R.J.; et al. Effects of increased nitrate intake from beetroot juice on blood markers of oxidative stress and inflammation in older adults with hypertension. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2024, 222, 519–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karimzadeh, L.; Behrouz, V.; Sohrab, G.; Hedayati, M.; Emami, G. A randomized clinical trial of beetroot juice consumption on inflammatory markers and oxidative stress in patients with type 2 diabetes. J. Food Sci. 2022, 87, 5430–5441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shepherd, A.I.; Costello, J.T.; Bailey, S.J.; Bishop, N.; Wadley, A.J.; Young-Min, S.; Gilchrist, M.; Mayes, H.; White, D.; Gorczynski, P. “Beet” the cold: Beetroot juice supplementation improves peripheral blood flow, endothelial function, and anti-inflammatory status in individuals with Raynaud’s phenomenon. J. Appl. Physiol. 2019, 127, 1478–1490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asgary, S.; Afshani, M.R.; Sahebkar, A.; Keshvari, M.; Taheri, M.; Jahanian, E.; Rafieian-Kopaei, M.; Malekian, F.; Sarrafzadegan, N. Improvement of hypertension, endothelial function and systemic inflammation following short-term supplementation with red beet (Beta vulgaris L.) juice: A randomized crossover pilot study. J. Hum. Hypertens. 2016, 30, 627–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vagelatos, N.T.; Eslick, G.D. Type 2 Diabetes as a Risk Factor for Alzheimer’s Disease: The Confounders, Interactions, and Neuropathology Associated with This Relationship. Epidemiol. Rev. 2013, 35, 152–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedrinolla, A.; Dorelli, G.; Porcelli, S.; Burleigh, M.; Mendo, M.; Martignon, C.; Fonte, C.; Dalle Carbonare, L.G.; Easton, C.; Muti, E.; et al. Increasing nitric oxide availability via ingestion of nitrate-rich beetroot juice improves vascular responsiveness in individuals with Alzheimer’s Disease. Nitric Oxide 2025, 156, 50–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, R.A.; Storm, W.L.; Coneski, P.N.; Schoenfisch, M.H. Inaccuracies of nitric oxide measurement methods in biological media. Anal. Chem. 2013, 85, 1957–1963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.Y.; Zhang, Y. Animal models of Alzheimer’s disease: Applications, evaluation, and perspectives. Zool. Res. 2022, 43, 1026–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clague, F.; Mercer, S.W.; McLean, G.; Reynish, E.; Guthrie, B. Comorbidity and polypharmacy in people with dementia: Insights from a large, population-based cross-sectional analysis of primary care data. Age Ageing 2016, 46, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trindade, L.R.D.; Baião, D.D.S.; da Silva, D.V.T.; Almeida, C.C.; Pauli, F.P.; Ferreira, V.F.; Conte-Junior, C.A.; Paschoalin, V.M.F. Microencapsulated and Ready-to-Eat Beetroot Soup: A Stable and Attractive Formulation Enriched in Nitrate, Betalains and Minerals. Foods 2023, 12, 1497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shannon, O.M.; Mathers, J.C.; Stevenson, E.; Siervo, M. Healthy dietary patterns, cognition and dementia risk: Current evidence and context. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2025, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Compounds | Neuroprotective Properties | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| GT 715 and GT 061 (S-nitrates) | Reversal of cognitive deficits via NO/cGMP/ERK–CREB pathways. | [37] |

| MN-08 (memantine with a nitrate group) | Reversal of cognitive deficits, with greater efficacy than standard memantine. Increased cerebral blood flow, reduced neuronal loss and white matter injury and activated pro-survival signalling pathways associated with neuronal resilience. | [38] |

| S-nitrosoglutathione | Reversal of cognitive deficits, with greater efficacy than (NOS dependent) L-Arginine. Reduced neuronal damage and amyloid β, and upregulation of brain derived neurotropic factor and Nuclear Factor Erythroid 2-Related Factor-2 antioxidant signalling pathways | [39,40] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kimble, R.; Shannon, O.M. Can Beetroot (Beta vulgaris) Support Brain Health? A Perspective Review on Alzheimer’s Disease. Nutrients 2025, 17, 3790. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17233790

Kimble R, Shannon OM. Can Beetroot (Beta vulgaris) Support Brain Health? A Perspective Review on Alzheimer’s Disease. Nutrients. 2025; 17(23):3790. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17233790

Chicago/Turabian StyleKimble, Rachel, and Oliver M. Shannon. 2025. "Can Beetroot (Beta vulgaris) Support Brain Health? A Perspective Review on Alzheimer’s Disease" Nutrients 17, no. 23: 3790. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17233790

APA StyleKimble, R., & Shannon, O. M. (2025). Can Beetroot (Beta vulgaris) Support Brain Health? A Perspective Review on Alzheimer’s Disease. Nutrients, 17(23), 3790. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17233790