Inhibitory Effect of Canavalia gladiata Extract on Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans LPS Induced Nitric Oxide in Macrophages

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Extraction of Canavalia gladiata with 0.5 M NaCl (CGENa)

2.2. Chemicals and Reagents

2.3. Bacterial Strains

2.4. Preparation of Erythrocytes

2.5. Hemagglutination Assay

2.6. Extraction of A. actinomycetemcomitans LPS

2.7. Cytotoxicity Assessment

2.8. Nitric Oxide Measurement

2.9. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

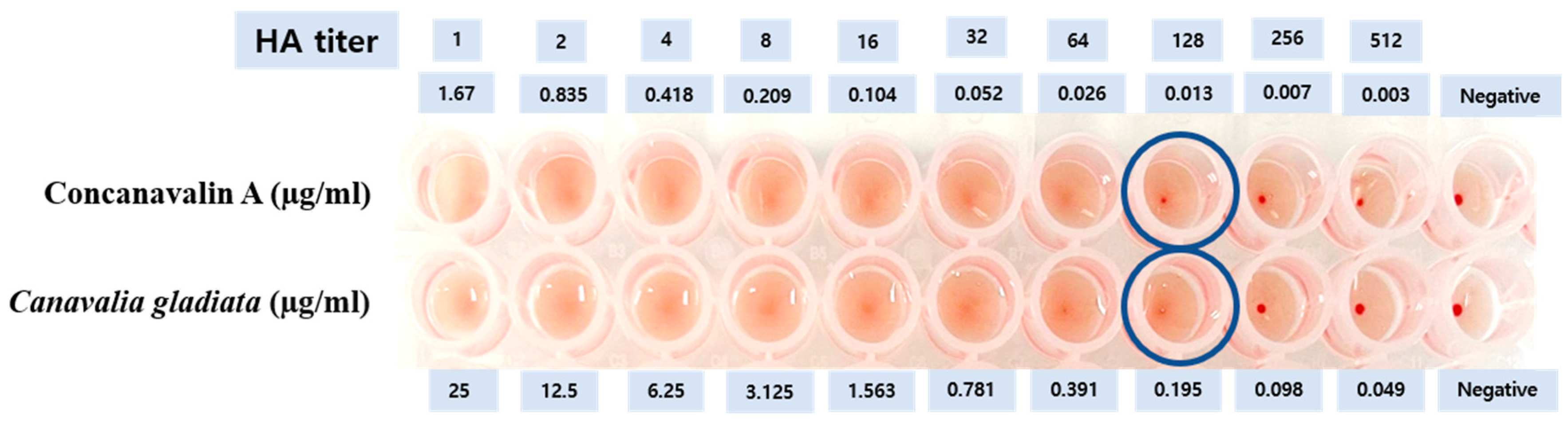

3.1. Analysis of Con Aeq in CGENa

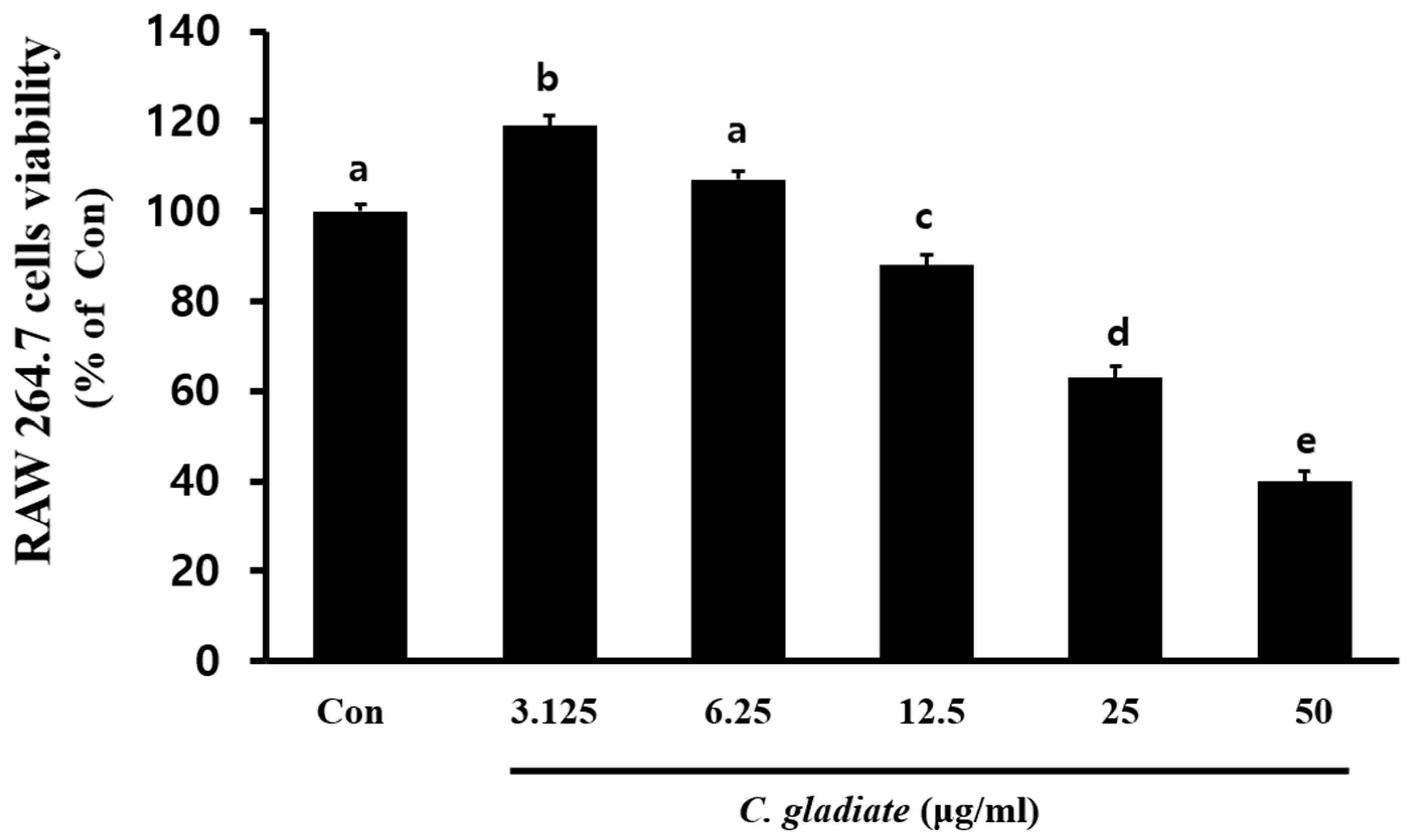

3.2. Cytotoxicity Assessment of CGENa

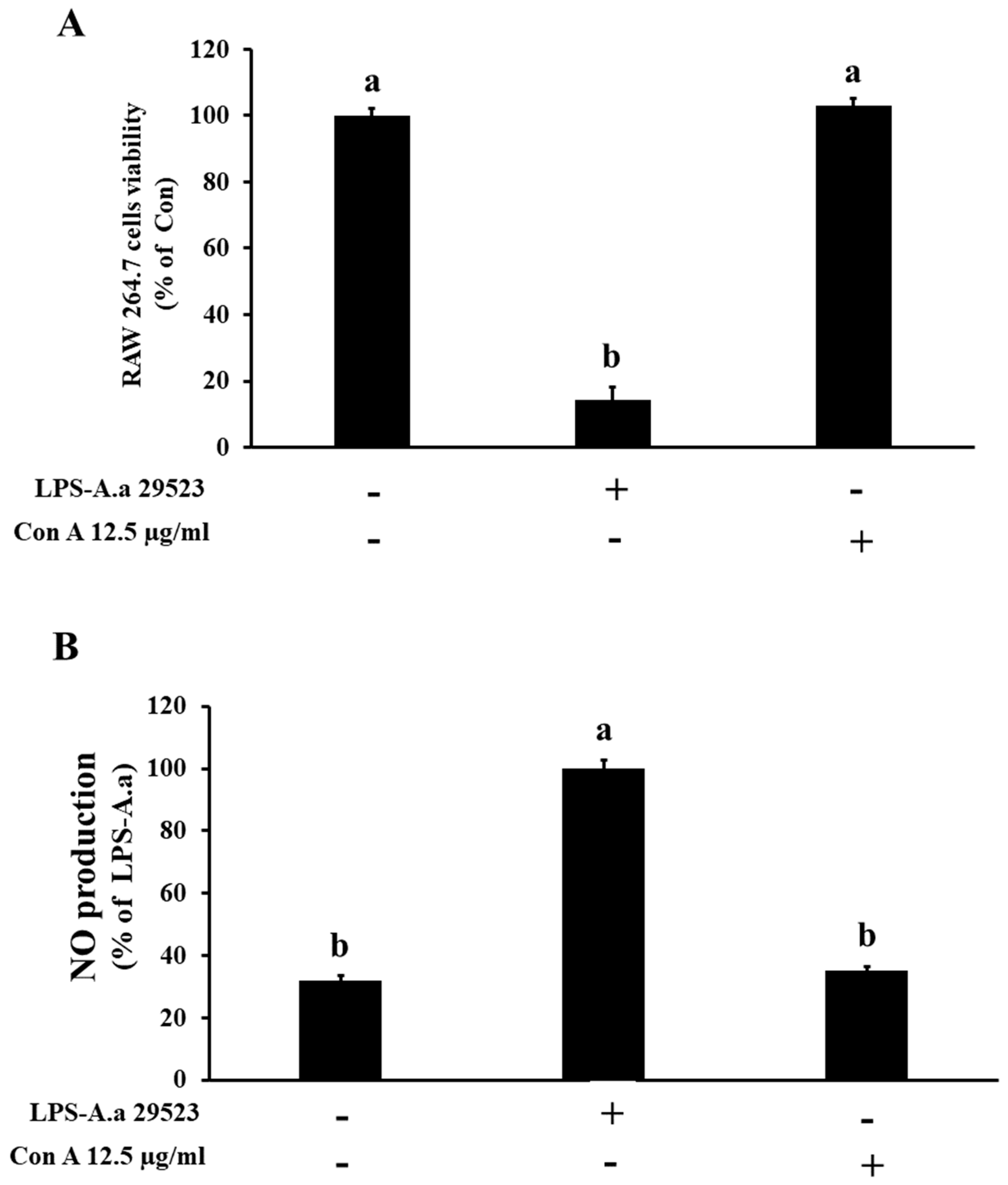

3.3. Analysis of NO Production by Con A, an Active Component of C. gladiata, in RAW 264.7 Cells

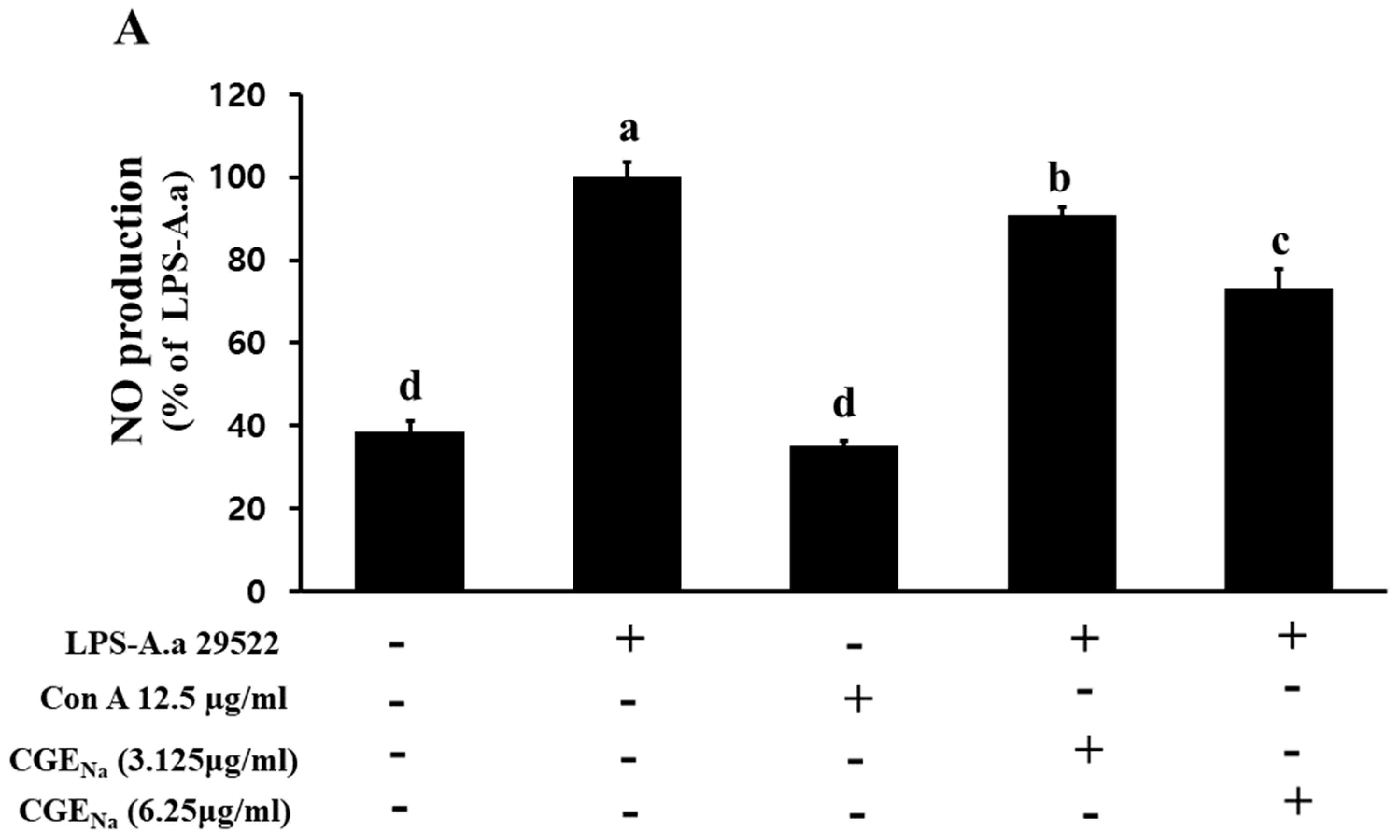

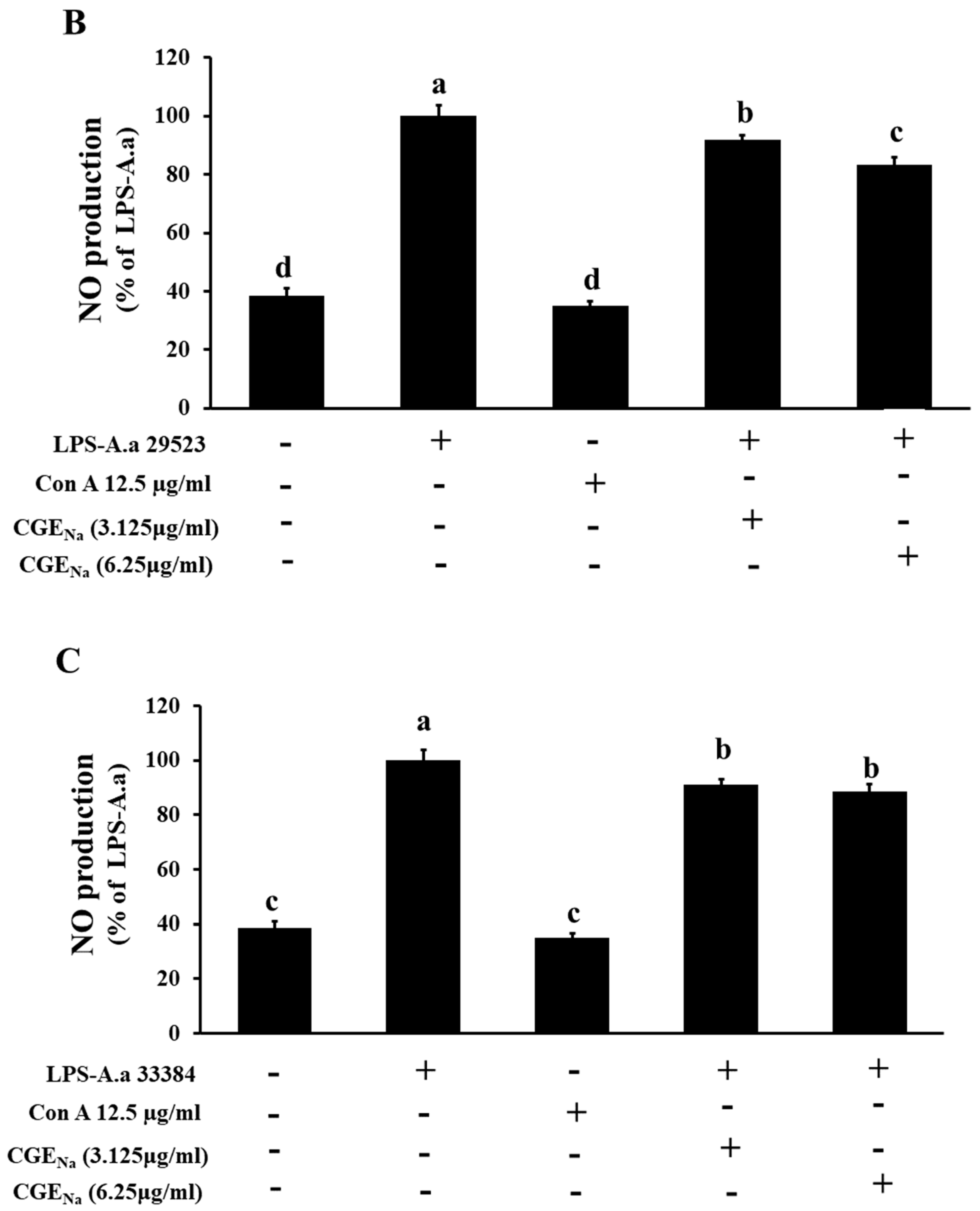

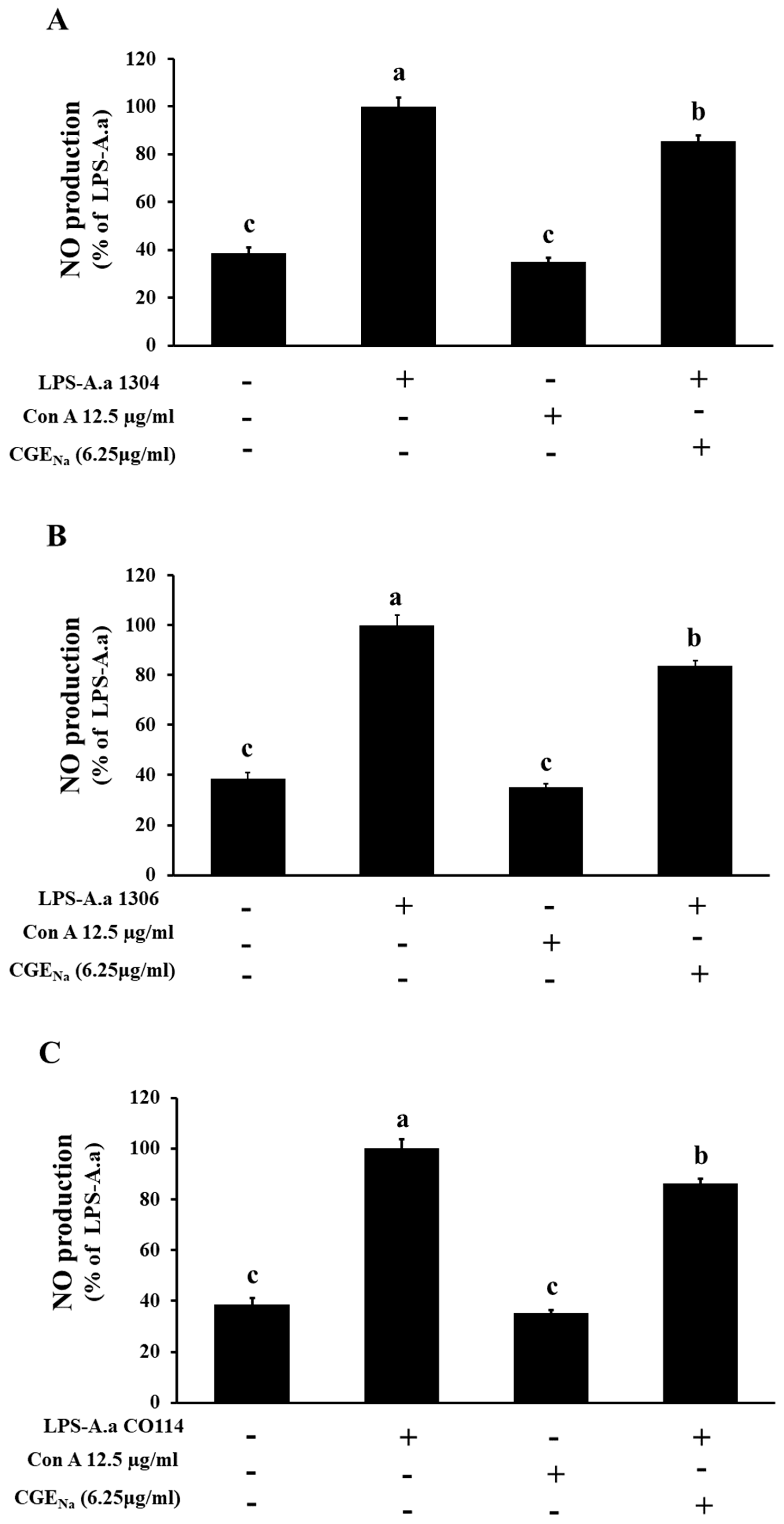

3.4. Inhibitory Effect of CGENa on NO Production in RAW 264.7 Cells

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jang, J.H.; Ji, K.-Y.; Choi, H.S.; Yang, W.K.; Kim, H.Y.; Kim, K.; Kang, H.S.; Lee, Y.C.; Kim, S.H. Suppression of colon cancer by administration of Canavalia gladiata D.C. and Arctium lappa L., Redix extracts in tumor-bearing mice model. Korean J. Herbol. 2017, 32, 27–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekanayake, S.; Skog, K.; Asp, N.G. Canavanine content in sword bean (Canavalia gladiata): Analysis and effect of processing. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2007, 45, 797–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jang, C.S.; Oh, M.-J.; No, G.S. Purification and biochemical characterization of lectin from Viscum album. Korean J. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 1999, 14, 578–584. [Google Scholar]

- Nishizawa, K.; Masuda, T.; Takenaka, Y.; Masui, H.; Tani, F.; Arii, Y. Precipitation of sword bean proteins by heating and addition of magnesium chloride in a crude extract. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2016, 80, 1623–1631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, H.C.; Kim, H.S.; Kim, E.H.; Moon, J.H. Antioxidant activity of coffee added with sword bean. Korean J. Food Preserv. 2020, 27, 385–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, H.C.; Park, J.U.; Moon, J.H. Anti-inflammatory effects of a mixture of coffee and sword bean extracts. Korean J. Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 52, 237–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, K.-A.; Heo, W.; Hwang, H.-J.; Han, B.K.; Song, M.C.; Kim, Y.J. Anti-Inflammatory Effect of Immature Sword Bean Pod (Canavalia gladiata) in Lipopolysaccharide-Induced RAW264.7 Cells. J. Med. Food. 2020, 23, 1183–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, H.; Meng, D.; Yue, L.; Xu, H.; Feng, K.; Wang, J. Ethnobotanical Use, Phytochemistry, Pharmacology, and Toxicity of Canavalia gladiata. Drug Des. Devel. Ther. 2025, 19, 3779–3803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, K.S.; Na, H.J.; Kim, Y.M.; Kwon, H.J. Antiangiogenic activity of 4-O-methylgallic acid from Canavalia gladiata, dietary legume. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2005, 330, 1268–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nimenibo-Uadia, R. Effect of aqueous extract of Canavalia ensiformis seeds on hyperlipidaemia and hyperketonaemia in alloxan-induced diabetic rats. Biokemistri 2003, 15, 7–15. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J.P.; Lee, H.H.; Moon, J.H.; Ha, D.R.; Kim, E.S.; Kim, J.H.; Seo, K.W. Isolation and identification of antioxidants from methanol extract of sword bean (Canavalia gladiata). Korean J. Food Sci. Technol. 2013, 45, 777–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.J.; Park, J.U.; Guo, R.H.; Kang, B.Y.; Park, I.K.; Kim, Y.R. Anti-inflammatory effects of Canavalia gladiata in macrophage cells and DSS-induced colitis mouse model. Am. J. Chin. Med. 2019, 47, 1571–1588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.Y.; Jeong, H.S. Isolation and Identification of Antimicrobial Substance from Canavalia gladiata. Food Sci. Biotechnol. 2005, 14, 268–274. [Google Scholar]

- Chung, J.; Lee, J.; Ha, D. Antimicrobial Activities of Sword Bean (Canavalia gladiata) Extracts Against Food Poisoning Bacteria. J. Food Hyg. Saf. 2014, 29, 376–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Moon, H.; Jeong, Y.; Park, J.; Kim, Y.R. Antioxidant, Skin Whitening, and Antibacterial Effects of Canavalia gladiata Extracts. Med. Biol. Sci. Eng. 2018, 1, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Nakatsuka, Y.; Nagasawa, T.; Yumoto, Y.; Nakazawa, F.; Furuichi, Y. Inhibitory effects of sword bean extract on alveolar bone resorption induced in rats by Porphyromonas gingivalis infection. J. Periodontal Res. 2014, 49, 801–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sosroseno, W.; Herminajeng, E. The immunopathology of chronic inflammatory periodontal disease. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 1995, 10, 171–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, D.H.; Fives Taylor, P.M. The role of Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans in the pathogenesis of periodontal disease. Trends Microbiol. 1997, 5, 224–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, M.; Reddi, K.; Henderson, B. Cytokine-inducing components of periodontopathogenic bacteria. J. Periodontal Res. 1996, 31, 393–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien-Simpson, N.M.; Veith, P.D.; Dashper, S.G.; Reynolds, E.C. Antigens of bacteria associated with periodontitis. Periodontol. 2000 2004, 35, 101–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bodet, C.; Chandad, F.; Grenier, D. Anti-inflammatory activity of a high-molecular-weight cranberry fraction on macrophages stimulated by lipopolysaccharides from periodontopathogens. J. Dent. Res. 2006, 85, 235–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blix, I.J.S.; Helgeland, K. LPS from Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans and production of nitric oxide in murine macrophages J774. Eur. J. Oral Sci. 1998, 106, 576–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, P.C.; Ochoa, A.C.; Al Khami, A.A. Arginine metabolism in myeloid cells shapes innate and adaptive immunity. Front. Immunol. 2017, 8, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özdemir, B.; Özmeric, N.; Elgün, S.; Barış, E. Smoking and gingivitis: Focus on inducible nitric oxide synthase, nitric oxide and basic fibroblast growth factor. J. Periodontal Res. 2016, 51, 596–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucarini, G.; Tirabassi, G.; Zizzi, A.; Balercia, G.; Quaranta, A.; Rubini, C.; Aspriello, S.D. Uncoupling of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) in gingival tissue of type 2 diabetic patients. Inflammation 2016, 39, 632–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gyurko, R.; Shoji, H.; Battaglino, R.A.; Boustany, G.; Gibson, F.C.; Genco, C.A.; Stashenko, P.; Van Dyke, T.E. Inducible nitric oxide synthase mediates bone development and P. gingivalis-induced alveolar bone loss. Bone 2005, 36, 472–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, M.J.; Sousa, L.M.; Lara, V.P.; Cardoso, F.P.; Júnior, G.M.; Totola, A.H.; Caliari, M.V.; Romero, O.B.; Silva, G.A.; Ribeiro-Sobrinho, A.P.; et al. The role of iNOS and PHOX in periapical bone resorption. J. Dent. Res. 2011, 90, 495–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herbert, B.A.; Novince, C.M.; Kirkwood, K.L. Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans, a potent immunoregulator of the periodontal host defense system and alveolar bone homeostasis. Mol. Oral Microbiol. 2016, 31, 207–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Han, L.; Xia, L.; Yuan, Y.; Hu, H. Assessment of hemagglutination activity of porcine deltacoronavirus. J. Vet. Sci. 2020, 21, e12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posadas, I.; Terencio, M.C.; Guillén, I.; Ferrándiz, M.L.; Coloma, J.; Payá, M.; Alcaraz, M.J. Co-regulation between cyclo-oxygenase-2 and inducible nitric oxide synthase expression in the time course of murine inflammation. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch. Pharmacol. 2000, 361, 98–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kojima, A.K.; Ogawa, H.; Seno, N.; Matsumoto, I. Purification and characterization of Canavalia gladiata agglutinin. Carbohydr. Res. 1991, 213, 275–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Liu, Y.; Yang, X.; Li, C.; Song, Z. The oral microbiota: Community composition, influencing factors, pathogenesis, and interventions. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 895537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, R.G.; Gillespie, W.A. Bacterial endocarditis due to an Actinobacillus. J. Clin. Pathol. 1964, 17, 511–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paturel, L.; Casalta, J.-P.; Habib, G.; Nezri, M.; Raoult, D. Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans endocarditis. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2004, 10, 98–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nørskov-Lauritsen, N.; Claesson, R.; Jensen, A.B.; Åberg, C.H.; Haubek, D. Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans: Clinical significance of a pathobiont subjected to ample changes in classification and nomenclature. Pathogens 2019, 8, 243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fives-Taylor, P.M.; Meyer, D.H.; Mintz, K.P.; Brissette, C. Virulence factors of Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans. Periodontol. 2000 1999, 20, 136–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, H.; Fukusaki, Y.; Yoshimura, A.; Shiraishi, C.; Kishimoto, M.; Kaneko, T.; Hara, Y. Lack of toll-like receptor 4 decreases lipopolysaccharide-induced bone resorption in C3H/HeJ mice in vivo. Oral Microbiol. Immunol. 2008, 23, 190–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feres, M.; Figueiredo, L.C.; Soares, G.M.S.; Faveri, M. Systemic antibiotics in the treatment of periodontitis. Periodontol. 2000 2015, 67, 131–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mensah, A.; Rodgers, A.M.; Larrañeta, E.; McMullan, L.; Tambuwala, M.; Callan, J.F.; Courtenay, A.J. Treatment of periodontal infections: The possible role of hydrogels as antibiotic drug-delivery systems. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballerstadt, R.; Evans, C.; McNichols, R.; Gowda, A. Concanavalin A for in vivo glucose sensing: A biotoxicity review. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2006, 22, 275–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.J.; Kim, I.S.; Kim, J.C.; Shyn, K.H. The role of nitric oxide on cataractogenesis in uveitis model induced by concanavalin A and lipopolysaccharide. J. Korean Ophthalmol. Soc. 2000, 41, 562–575. [Google Scholar]

- Sodhi, A.; Tarang, S.; Kesherwani, V. Concanavalin A induced expression of toll-like receptors in murine peritoneal macrophages in vitro. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2007, 7, 454–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade, J.L.; Arruda, S.; Barbosa, T.; Paim, L.; Ramos, M.V.; Cavada, B.S.; Barral-Netto, M. Lectin-induced nitric oxide production. Cell. Immunol. 1999, 194, 98–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanessa, H.; Daniel, G.; Fatiha, C. Protective effects of grape seed proanthocyanidins against oxidative stress induced by lipopolysaccharides of periodontopathogens. J. Periodontol. 2006, 77, 1371–1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sosroseno, W.; Barid, I.; Herminajeng, E.; Susilowati, H. Nitric oxide production by a murine macrophage cell line (RAW264.7) stimulated with lipopolysaccharide from Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans. Oral Microbiol Immunol. 2002, 17, 72–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Substance | The Concentration (µg/mL) | |

|---|---|---|

| CGENa | 25 | 6.25 |

| Con Aeq | 1.67 | 0.4175 |

| Group | LPS-A.a | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 29522 | 29523 | 33384 | 1304 | 1306 | CO114 | |

| Con | 38.6 ± 2.5 a | 38.6 ± 2.5 a | 38.6 ± 2.4 a | 38.6 ± 2.4 a | 38.6 ± 2.2 a | 38.6 ± 2.1 a |

| LPS | 100.0 ± 3.5 c | 100.0 ± 3.7 c | 100.1 ± 3.8 c | 99.9 ± 3.8 c | 100.0 ± 3.6 c | 100.0 ± 4.9 c |

| Con A | 35.1 ± 1.6 a | 35.1 ± 1.5 a | 35.1 ± 1.6 a | 35.1 ± 1.6 a | 35.2 ± 2.1 a | 35.1 ± 1.3 a |

| CGENa | 73.2 ± 4.6 b | 83.5 ± 3.3 b | 88.6 ± 2.7 b | 85.6 ± 1.8 b | 83.5 ± 2.3 b | 86.4 ± 1.7 b |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kim, E.-S.; Lee, Y.-S.; Kang, J.; Kim, K.-J.; You, Y.-O. Inhibitory Effect of Canavalia gladiata Extract on Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans LPS Induced Nitric Oxide in Macrophages. Nutrients 2025, 17, 3764. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17233764

Kim E-S, Lee Y-S, Kang J, Kim K-J, You Y-O. Inhibitory Effect of Canavalia gladiata Extract on Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans LPS Induced Nitric Oxide in Macrophages. Nutrients. 2025; 17(23):3764. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17233764

Chicago/Turabian StyleKim, Eun-Sook, Yun-Seong Lee, Jooyi Kang, Kang-Ju Kim, and Yong-Ouk You. 2025. "Inhibitory Effect of Canavalia gladiata Extract on Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans LPS Induced Nitric Oxide in Macrophages" Nutrients 17, no. 23: 3764. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17233764

APA StyleKim, E.-S., Lee, Y.-S., Kang, J., Kim, K.-J., & You, Y.-O. (2025). Inhibitory Effect of Canavalia gladiata Extract on Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans LPS Induced Nitric Oxide in Macrophages. Nutrients, 17(23), 3764. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17233764