Body Composition and Eating Habits in Newly Diagnosed Graves’ Disease Patients Compared with Euthyroid Controls

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patients

2.2. Anthropometric Measurements

2.3. Thyroid Function Parameters

2.4. Thyroid Volume

2.5. Body Composition Analysis

- -

- Body cell mass index (BCMI): obtained dividing BCM by the square height in meters (BCM/height2) [11].

- -

2.6. Dietary Assessment

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Clinical, Anthropometric and Biochemical Characteristics and Body Composition of the GD Group

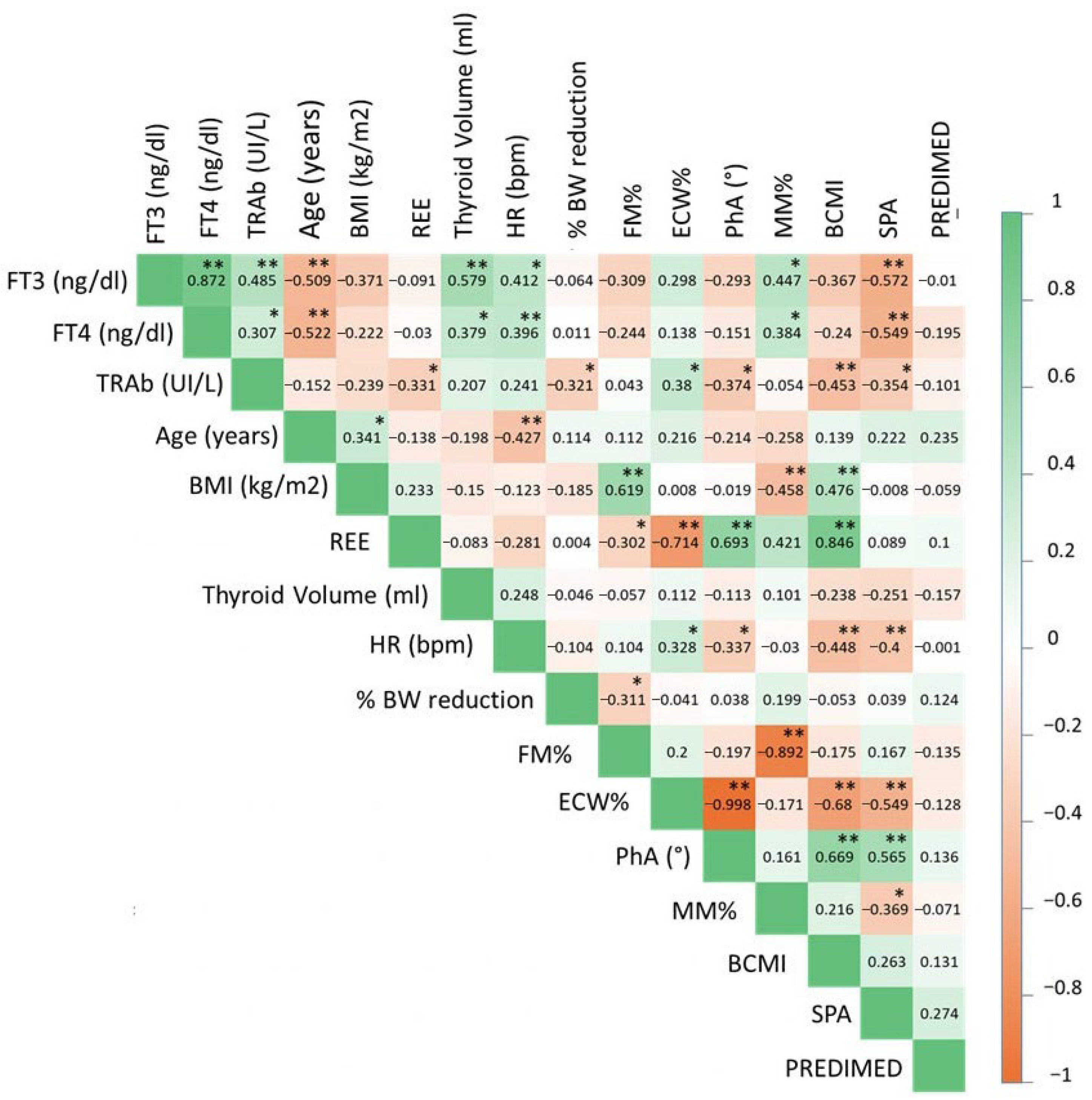

3.2. Correlation Between Severity of Hyperthyroidism and Clinical, Anthropometric and Biochemical Characteristics, Body Composition and Eating Behavior in the GD Group

3.3. Comparison of Body Composition and Adherence to the Mediterranean Diet Between GD Patients and Controls

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- Kyriacou, A.; Makris, K.C.; Syed, A.A.; Perros, P. Weight gain following treatment of hyperthyroidism—A forgotten tale. Clin. Obes. 2019, 9, e12328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lönn, L.; Stenlöf, K.; Ottosson, M.; Lindroos, A.K.; Nyström, E.; Sjöström, L. Body weight and body composition changes after treatment of hyperthyroidism. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 1998, 83, 4269–4273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chng, C.L.; Lim, A.Y.; Tan, H.C.; Kovalik, J.P.; Tham, K.W.; Bee, Y.M.; Lim, W.; Acharyya, S.; Lai, O.F.; Chong, M.F.-F.; et al. Physiological and Metabolic Changes During the Transition from Hyperthyroidism to Euthyroidism in Graves’ Disease. Thyroid 2016, 26, 1422–1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, Z.; Chen, Q.; Ling, Y. Weight Gain and Body Composition Changes during the Transition of Thyroid Function in Patients with Graves’ Disease Undergoing Radioiodine Treatment. Int. J. Endocrinol. 2022, 2022, 5263973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acotto, C.G.; Niepomniszcze, H.; Mautalen, C.A. Estimating body fat and lean tissue distribution in hyperthyroidism by dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry. J. Clin. Densitom. 2002, 5, 305–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovejoy, J.C.; Smith, S.R.; Bray, G.A.; DeLany, J.P.; Rood, J.C.; Gouvier, D.; Windhauser, M.; Ryan, D.H.; Macchiavelli, R.; Tulley, R. A paradigm of experimentally induced mild hyperthyroidism: Effects on nitrogen balance, body composition, and energy expenditure in healthy young men. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 1997, 82, 765–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chumlea, W.C.; Guo, S.S. Bioelectrical impedance and body composition: Present status and future directions. Nutr. Rev. 1994, 52, 123–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seppel, T.; Kosel, A.; Schlaghecke, R. Bioelectrical impedance assessment of body composition in thyroid disease. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 1997, 136, 493–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.Y.; Kato, Y. Body composition assessed by bioelectrical impedance analysis (BIA) in patients with Graves’ disease before and after treatment. Endocr. J. 1995, 42, 545–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Sciacchitano, S.; Napoli, A.; Rocco, M.; De Vitis, C.; Mancini, R. Myxedema in Both Hyperthyroidism and Hypothyroidism: A Hormetic Response? Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 9957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rondanelli, M.; Talluri, J.; Peroni, G.; Donelli, C.; Guerriero, F.; Ferrini, K.; Riggi, E.; Sauta, E.; Perna, S.; Guido, D. Beyond Body Mass Index. Is the Body Cell Mass Index (BCMI) a useful prognostic factor to describe nutritional, inflammation and muscle mass status in hospitalized elderly?: Body Cell Mass Index links in elderly. Clin. Nutr. 2018, 37, 934–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matthews, L.; Bates, A.; Wootton, S.A.; Levett, D. The use of bioelectrical impedance analysis to predict post-operative complications in adult patients having surgery for cancer: A systematic review. Clin. Nutr. 2021, 40, 2914–2922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paiva, S.I.; Borges, L.R.; Halpern-Silveira, D.; Assunção, M.C.; Barros, A.J.; Gonzalez, M.C. Standardized phase angle from bioelectrical impedance analysis as prognostic factor for survival in patients with cancer. Support. Care Cancer 2010, 19, 187–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Norman, K.; Stobäus, N.; Zocher, D.; Bosy-Westphal, A.; Szramek, A.; Scheufele, R.; Smoliner, C.; Pirlich, M. Cutoff percentiles of bioelectrical phase angle predict functionality, quality of life, and mortality in patients with cancer. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2010, 92, 612–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emir, K.N.; Demirel, B.; Atasoy, B.M. An Investigation of the Role of Phase Angle in Malnutrition Risk Evaluation and Clinical Outcomes in Patients with Head and Neck or Brain Tumors Undergoing Radiotherapy. Nutr. Cancer 2024, 76, 252–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyakawa, M.; Tsushima, T.; Murakami, H.; Isozaki, O.; Takano, K. Serum leptin levels and bioelectrical impedance assessment of body composition in patients with Graves’ disease and hypothyroidism. Endocr. J. 1999, 46, 665–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukackiene, D.; Rimsevicius, L.; Miglinas, M. Standardized Phase Angle for Predicting Nutritional Status of Hemodialysis Patients in the Early Period After Deceased Donor Kidney Transplantation. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 803002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genton, L.; Norman, K.; Spoerri, A.; Pichard, C.; Karsegard, V.L.; Herrmann, F.R.; Graf, C.E. Bioimpedance-Derived Phase Angle and Mortality Among Older People. Rejuvenation Res. 2017, 20, 118–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roccamatisi, L.; Gianotti, L.; Paiella, S.; Casciani, F.; De Pastena, M.; Caccialanza, R.; Bassi, C.; Sandini, M. Preoperative standardized phase angle at bioimpedance vector analysis predicts the outbreak of antimicrobial-resistant infections after major abdominal oncologic surgery: A prospective trial. Nutrition 2021, 86, 111184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornejo-Pareja, I.; Vegas-Aguilar, I.M.; García-Almeida, J.M.; Bellido-Guerrero, D.; Talluri, A.; Lukaski, H.; Tinahones, F.J. Phase angle and standardized phase angle from bioelectrical impedance measurements as a prognostic factor for mortality at 90 days in patients with COVID-19: A longitudinal cohort study. Clin. Nutr. 2022, 41, 3106–3114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prior-Sánchez, I.; Herrera-Martínez, A.D.; Zarco-Martín, M.T.; Fernández-Jiménez, R.; Gonzalo-Marín, M.; Muñoz-Garach, A.; Vilchez-López, F.J.; Cayón-Blanco, M.; Villarrubia-Pozo, A.; Muñoz-Jiménez, C.; et al. Prognostic value of bioelectrical impedance analysis in head and neck cancer patients undergoing radiotherapy: A VALOR® study. Front. Nutr. 2024, 11, 1335052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkemade, A.; Vuijst, C.L.; Unmehopa, U.A.; Bakker, O.; Vennström, B.; Wiersinga, W.M.; Swaab, D.F.; Fliers, E. Thyroid hormone receptor expression in the human hypothalamus and anterior pituitary. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2005, 90, 904–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pijl, H.; de Meijer, P.H.; Langius, J.; Coenegracht, C.I.; van den Berk, A.H.; Chandie Shaw, P.K.; Boom, H.; Schoemaker, R.C.; Cohen, A.F.; Burggraaf, J.; et al. Food choice in hyperthyroidism: Potential influence of the autonomic nervous system and brain serotonin precursor availability. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2001, 86, 5848–5853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, W.H.; Spina, R.J.; Korte, E.; Yarasheski, K.E.; Angelopoulos, T.J.; Nemeth, P.M.; Saffitz, J.E. Mechanisms of impaired exercise capacity in short duration experimental hyperthyroidism. J. Clin. Investig. 1991, 88, 2047–2053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuboki, T.; Suematsu, H.; Ogata, E.; Yamamoto, M.; Shizume, K. Two cases of anorexia nervosa associated with Graves’ disease. Endocrinol. Jpn. 1987, 34, 9–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| GD Patients Who Lost Weight (32) | GD Patients Who Did Not Lose Weight (12) | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (Years, mean ± SD) | 47.0 ± 15.4 | 48.4 ± 15.4 | 0.792 |

| Gender (Male/Female, % of Males) | 10/22 (31.3%) | 1/11 (8.3%) | 0.118 |

| BMI at diagnosis (kg/m2, mean ± SD) | 22.6 ± 4.1 | 24.4 ± 5.3 | 0.234 |

| Pre-morbid BMI (kg/m2, mean ± SD) | 24.7 ± 4.7 | 24.0 ± 4.9 | 0.645 |

| Body weight variation (kg, median, 25–75° centile) | −6.5 (−3.7–10.6) | 0.5 (0.0–2.1) | <0.001 |

| % Body weight variation (%, median, 25–75° centile) | −4.0 (−2.5–−7.4) | 0.4 (0.0–3.4) | <0.001 |

| Heart rate (bpm, mean ± SD) | 86.3 ± 15.6 | 91.9 ± 20.9 | 0.348 |

| PhA (°, mean ± SD) | 5.0 ± 0.7 | 4.8 ± 0.8 | 0.604 |

| SPA (median, 25–75° centile) | −0.4 (−1.5–0.4) | −0.3 (−1.3–0.4) | 0.687 |

| ECW (%, mean ± SD) | 51.4 ± 4.5 | 52.2 ± 4.6 | 0.590 |

| BCMI (mean ± SD) | 8.2 ± 1.5 | 7.8 ± 1.1 | 0.407 |

| FM% (%, mean ± SD) | 23.1 ± 9.4 | 30.5 ± 9.0 | 0.024 |

| MM% (%, mean ± SD) | 37.5 ± 8.0 | 31.7 ± 5.9 | 0.027 |

| Resting Energy Expenditure (kcal/day, mean ± SD) | 1412.1 ± 160.5 | 1340.7 ± 87.5 | 0.153 |

| Regular physical activity (N, %) | |||

| Estimated daily caloric intake (kcal/day, mean ± SD) | 2053.8 ± 252.9 | 2331.6 ± 183.4 | <0.001 |

| PREDIMED score (median, 25–75° centile) | 6 (6–10) | 6 (5–8) | 0.490 |

| PREDIMED adherence level (N, %) | 0.471 | ||

| Low | 7 (21.9%) | 3 (25.0%) | |

| Moderate | 17 (53.10%) | 8 (66.7%) | |

| High | 8 (25.0%) | 1 (8.3%) | |

| Fat intake (reduced, adequate, increased, N %) | 3 (9.4%), 14 (43.8%), 15 (46.9%) | 0 (0.0%), 9 (75.0%), 3 (25.0%) | 0.151 |

| Carbohydrate intake (reduced, adequate, increased, N %) | 5 (15.6%), 19 (59.4%), 8 (25.0%) | 2 (6.7%), 8 (66.7%), 2 (16.7%) | 0.840 |

| Fiber intake (reduced, adequate, N %) | 21 (77.8%), 11 (34.4%) | 6 (50.0%), 6 (50.0%) | 0.343 |

| Water intake (reduced, adequate, increased, N %) | 9 (28.1%), 23 (71.9%) | 3 (25.0%), 9 (75.0%) | 0.836 |

| FT3 (pg/mL, median, 25–75° centile) | 6.8 (4.5–11.2) | 9.0 (4.3–17.7) | 0.727 |

| FT4 (pg/mL, median, 25–75° centile) | 20.8 (16.9–31.1) | 21.0 (18.1–30.5) | 0.969 |

| TRAb (U/L, median, 25–75° centile) | 7.5 (3.3–12.9) | 16.0 (11.1–17.1) | 0.011 |

| β | C.I. for β | p Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||

| FT3 | −0.446 | −0.861 | −0.031 | 0.036 |

| FT4 | −0.445 | −0.778 | −0.111 | 0.010 |

| TRAb | −0.332 | −0.619 | −0.045 | 0.025 |

| GD Patients (44) | Controls (44) | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years, mean ± SD) | 47.4 ± 15.2 | 43.4 ± 16.7 | 0.240 |

| Gender (Male/Female, % of Males) | 11/33 (25.0%) | 10/34 (22.7%) | 0.803 |

| BMI at diagnosis (kg/m2, mean ± SD) | 23.1 ± 4.5 | 22.9 ± 3.3 | 0.816 |

| Resting Energy Expenditure (kcal, mean ± SD) | 1392.6 ± 146.8 | 1456.6 ± 154.8 | 0.050 |

| PhA (°, mean ± SD) | 4.9 ± 0.7 | 5.6 ± 0.7 | <0.001 |

| SPA (median, 25–75° centile) | −0.4 (−1.3–0.4) | 0.6 (−0.1–1.0) | <0.001 |

| ECW (%,mean ± SD) | 51.6 ± 4.5 | 47.6 ± 3.5 | <0.001 |

| BCMI (mean ± SD | 8.1 ± 1.4 | 9.0 ± 1.5 | 0.004 |

| FM% (mean ± SD) | 25.1 ± 9.8 | 23.8 ± 7.0 | 0.461 |

| MM% (mean ± SD) | 35.9 ± 7.8 | 36.4 ± 6.3 | 0.780 |

| PREDIMED score | 6 (6–9) | 7 (6–9) | 0.251 |

| PREDIMED adherence level (N, %) | 0.451 | ||

| Low | 10 (22.7%) | 8 (18.2%) | |

| Moderate | 25 (56.8%) | 30 (68.2%) | |

| High | 9 (20.5%) | 6 (13.6%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Croce, L.; Pallavicini, C.; Gabba, V.; Teliti, M.; Cipolla, A.; Gallotti, B.; Costa, P.; Cazzulani, B.; Magri, F.; Rotondi, M. Body Composition and Eating Habits in Newly Diagnosed Graves’ Disease Patients Compared with Euthyroid Controls. Nutrients 2025, 17, 3750. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17233750

Croce L, Pallavicini C, Gabba V, Teliti M, Cipolla A, Gallotti B, Costa P, Cazzulani B, Magri F, Rotondi M. Body Composition and Eating Habits in Newly Diagnosed Graves’ Disease Patients Compared with Euthyroid Controls. Nutrients. 2025; 17(23):3750. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17233750

Chicago/Turabian StyleCroce, Laura, Cristina Pallavicini, Vittorio Gabba, Marsida Teliti, Alessandro Cipolla, Benedetta Gallotti, Pietro Costa, Benedetta Cazzulani, Flavia Magri, and Mario Rotondi. 2025. "Body Composition and Eating Habits in Newly Diagnosed Graves’ Disease Patients Compared with Euthyroid Controls" Nutrients 17, no. 23: 3750. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17233750

APA StyleCroce, L., Pallavicini, C., Gabba, V., Teliti, M., Cipolla, A., Gallotti, B., Costa, P., Cazzulani, B., Magri, F., & Rotondi, M. (2025). Body Composition and Eating Habits in Newly Diagnosed Graves’ Disease Patients Compared with Euthyroid Controls. Nutrients, 17(23), 3750. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17233750