Association Between Mini Nutritional Assessment and Health Related Quality of Life in Chinese Older Adults: A Large Cross-Sectional Study Stratified by Chronic Disease Status

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Material & Methods

2.1. Study Samples

2.2. Nutritional Status Assessment

2.3. Health Related Quality of Life Measurement

2.4. Chronic Disease Assessment

2.5. Covariate Assessment

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Limitation

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. World Social Report 2024; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobanov-Rostovsky, S.; He, Q.; Chen, Y.; Liu, Y.; Wu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Venkatraman, T.; French, E.; Curry, N.; Hemmings, N.; et al. Growing old in China in socioeconomic and epidemiological context: Systematic review of social care policy for older people. BMC Public Health 2023, 23, 1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalache, A.; Gatti, A. Active ageing: A policy framework. Adv. Gerontol. 2003, 11, 7–18. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Group, W. Study protocol for the World Health Organization project to develop a Quality of Life assessment instrument (WHOQOL). Qual. Life Res. 1993, 2, 153–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojo-Perez, F.; Fernandez-Mayoralas, G.; Rodriguez-Rodriguez, V. Global Perspective on Quality in Later Life. In Global Handbook of Quality of Life: Exploration of Well-Being of Nations and Continents; Glatzer, W., Camfield, L., Møller, V., Rojas, M., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2015; pp. 469–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Liu, J.; Qu, B.; Yi, Z. Quality of life, loneliness and health-related characteristics among older people in Liaoning province, China: A cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 2018, 8, e021822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansson, I.; Joseph, P.; Balasubramanian, K.; McMurray, J.J.V.; Lund, L.H.; Ezekowitz, J.A.; Kamath, D.; Alhabib, K.; Bayes-Genis, A.; Budaj, A.; et al. Health-Related Quality of Life and Mortality in Heart Failure: The Global Congestive Heart Failure Study of 23,000 Patients From 40 Countries. Circulation 2021, 143, 2129–2142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çiftçi, S.; Erdem, M. Comparing nutritional status, quality of life and physical fitness: Aging in place versus nursing home residents. BMC Geriatr. 2025, 25, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Liu, P.; Huang, W.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, C.; Gao, T.; Zhong, F. Relationship between three dietary indices and health-related quality of life among rural elderly in China: A cross-sectional study. Front. Nutr. 2023, 10, 1259227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Jiao, J.; Zhu, C.; Zhu, M.; Wen, X.; Jin, J.; Wang, H.; Lv, D.; Zhao, S.; Wu, X.; et al. Associations Between Nutritional Status, Sociodemographic Characteristics, and Health-Related Variables and Health-Related Quality of Life Among Chinese Elderly Patients: A Multicenter Prospective Study. Front. Nutr. 2020, 7, 583161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, D.; Shu, X.; Zhou, G.; Ji, M.; Liao, G.; Zou, L. Connection between oral health and chronic diseases. MedComm 2025, 6, e70052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Efficace, F.; Rosti, G.; Breccia, M.; Cottone, F.; Giesinger, J.M.; Stagno, F.; Iurlo, A.; Russo Rossi, A.; Luciano, L.; Martino, B.; et al. The impact of comorbidity on health-related quality of life in elderly patients with chronic myeloid leukemia. Ann. Hematol. 2016, 95, 211–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stenvinkel, P.; Heimbürger, O.; Paultre, F.; Diczfalusy, U.; Wang, T.; Berglund, L.; Jogestrand, T. Strong association between malnutrition, inflammation, and atherosclerosis in chronic renal failure. Kidney Int. 1999, 55, 1899–1911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krok-Schoen, J.L.; Fanelli, S.; Pisegna, J.; Kelly, O.J.; Taylor, C.A. Poorer Diet Quality Observed in Older Adults with a Greater Number of Chronic Diseases. Innov. Aging 2019, 3, S261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cederholm, T.; Barazzoni, R.; Austin, P.; Ballmer, P.; Biolo, G.; Bischoff, S.C.; Compher, C.; Correia, I.; Higashiguchi, T.; Holst, M.; et al. ESPEN guidelines on definitions and terminology of clinical nutrition. Clin. Nutr. 2017, 36, 49–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guigoz, Y.; Lauque, S.; Vellas, B.J. Identifying the elderly at risk for malnutrition. The Mini Nutritional Assessment. Clin. Geriatr. Med. 2002, 18, 737–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guigoz, Y. The Mini Nutritional Assessment (MNA) review of the literature—What does it tell us? J. Nutr. Health Aging 2006, 10, 466–485; discussion 467–485. [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser, M.J.; Bauer, J.M.; Ramsch, C.; Uter, W.; Guigoz, Y.; Cederholm, T.; Thomas, D.R.; Anthony, P.; Charlton, K.E.; Maggio, M.; et al. Validation of the Mini Nutritional Assessment short-form (MNA®-SF): A practical tool for identification of nutritional status. JNHA-J. Nutr. Health Aging 2009, 13, 782–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubenstein, L.Z.; Harker, J.O.; Salvà, A.; Guigoz, Y.; Vellas, B. Screening for undernutrition in geriatric practice: Developing the short-form mini-nutritional assessment (MNA-SF). J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2001, 56, M366–M372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holvoet, E.; Vanden Wyngaert, K.; Van Craenenbroeck, A.H.; Van Biesen, W.; Eloot, S. The screening score of Mini Nutritional Assessment (MNA) is a useful routine screening tool for malnutrition risk in patients on maintenance dialysis. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0229722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apolone, G.; Mosconi, P. The Italian SF-36 Health Survey: Translation, Validation and Norming. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 1998, 51, 1025–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barile, J.P.; Horner-Johnson, W.; Krahn, G.; Zack, M.; Miranda, D.; DeMichele, K.; Ford, D.; Thompson, W.W. Measurement characteristics for two health-related quality of life measures in older adults: The SF-36 and the CDC Healthy Days items. Disabil. Health J. 2016, 9, 567–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bató, A.; Brodszky, V.; Rencz, F. Development of updated population norms for the SF-36 for Hungary and comparison with 1997–1998 norms. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2025, 23, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, X.; Yue, J.; Hou, L.; Xia, X.; Zuo, Z.; Liu, Y.; Jia, S.; Dong, B.; et al. Comorbid depressive and anxiety symptoms and frailty among older adults: Findings from the West China health and aging trend study. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 277, 970–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia, W.P.; Xiang, K.S.; Chen, L.; Lu, J.X.; Wu, Y.M. Epidemiological study on obesity and its comorbidities in urban Chinese older than 20 years of age in Shanghai, China. Obes. Rev. 2002, 3, 157–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adıgüzel, E.; Acar-Tek, N. Nutrition-related parameters predict the health-related quality of life in home care patients. Exp. Gerontol. 2019, 120, 15–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunvik, S.; Kanninen, J.-C.; Holm, A.; Suominen, M.H.; Kautiainen, H.; Puustinen, J. Nutritional Status and Health-Related Quality of Life among Home-Dwelling Older Adults Aged 75 Years: The PORI75 Study. Nutrients 2024, 16, 1713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papadopoulou, S.K.; Mantzorou, M.; Voulgaridou, G.; Pavlidou, E.; Vadikolias, K.; Antasouras, G.; Vorvolakos, T.; Psara, E.; Vasios, G.K.; Serdari, A.; et al. Nutritional Status Is Associated with Health-Related Quality of Life, Physical Activity, and Sleep Quality: A Cross-Sectional Study in an Elderly Greek Population. Nutrients 2023, 15, 443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganzel, B.L.; Morris, P.A.; Wethington, E. Allostasis and the human brain: Integrating models of stress from the social and life sciences. Psychol. Rev. 2010, 117, 134–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruins, M.J.; Van Dael, P.; Eggersdorfer, M. The Role of Nutrients in Reducing the Risk for Noncommunicable Diseases during Aging. Nutrients 2019, 11, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, M.H.; Nestler, E.J. Neural Substrates of Depression and Resilience. Neurotherapeutics 2017, 14, 677–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mądra-Gackowska, K.; Szewczyk-Golec, K.; Gackowski, M.; Hołyńska-Iwan, I.; Parzych, D.; Czuczejko, J.; Graczyk, M.; Husejko, J.; Jabłoński, T.; Kędziora-Kornatowska, K. Selected Biochemical, Hematological, and Immunological Blood Parameters for the Identification of Malnutrition in Polish Senile Inpatients: A Cross-Sectional Study. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Yang, Y.; Gao, Y.; Zhao, L.; Chen, L.; Sui, W.; Hu, J. The impact of chronic diseases on the health-related quality of life of middle-aged and older adults: The role of physical activity and degree of digitization. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 2335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, T.T.M.; Vu, M.T.; Luong, T.C.; Pham, K.M.; Nguyen, L.T.K.; Nguyen, M.H.; Do, B.N.; Nguyen, H.C.; Tran, T.V.; Nguyen, T.T.P.; et al. Negative Impact of Comorbidity on Health-Related Quality of Life Among Patients With Stroke as Modified by Good Diet Quality. Front. Med. 2022, 9, 836027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Q.; Wang, J. The Application and Mechanism Analysis of Enteral Nutrition in Clinical Management of Chronic Diseases. Nutrients 2025, 17, 450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, X.; Ferrier, J.A.; Jiang, H. Quality of life and associated factors among people with chronic diseases in Hubei, China: A cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 2025, 25, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heyworth, I.T.; Hazell, M.L.; Linehan, M.F.; Frank, T.L. How do common chronic conditions affect health-related quality of life? Br. J. Gen. Pract. 2009, 59, e353–e358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esposito, K.; Giugliano, D. Diet and inflammation: A link to metabolic and cardiovascular diseases. Eur. Heart J. 2006, 27, 15–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Liu, Y.; Li, Y.; Luo, B.; Lin, Z.; Chen, K.; Liu, Y. Dietary patterns and cardiometabolic health: Clinical evidence and mechanism. MedComm 2023, 4, e212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mądra-Gackowska, K.; Szewczyk-Golec, K.; Gackowski, M.; Woźniak, A.; Kędziora-Kornatowska, K. Evaluation of Selected Parameters of Oxidative Stress and Adipokine Levels in Hospitalized Older Patients with Diverse Nutritional Status. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaminsky, L.A.; German, C.; Imboden, M.; Ozemek, C.; Peterman, J.E.; Brubaker, P.H. The importance of healthy lifestyle behaviors in the prevention of cardiovascular disease. Prog. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2022, 70, 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Chi, X.; Wang, Y.; Setrerrahmane, S.; Xie, W.; Xu, H. Trends in insulin resistance: Insights into mechanisms and therapeutic strategy. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2022, 7, 216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kupczyk, D.; Bilski, R.; Szeleszczuk, Ł.; Mądra-Gackowska, K.; Studzińska, R. The Role of Diet in Modulating Inflammation and Oxidative Stress in Rheumatoid Arthritis, Ankylosing Spondylitis, and Psoriatic Arthritis. Nutrients 2025, 17, 1603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aggarwal, R.; Bains, K. Protein, lysine and vitamin D: Critical role in muscle and bone health. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2020, 62, 2548–2559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cervo, M.M.; Shivappa, N.; Hebert, J.R.; Oddy, W.H.; Winzenberg, T.; Balogun, S.; Wu, F.; Ebeling, P.; Aitken, D.; Jones, G.; et al. Longitudinal associations between dietary inflammatory index and musculoskeletal health in community-dwelling older adults. Clin. Nutr. 2020, 39, 516–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Fu, Y.; Zhu, Z. Association between dietary protein intake and bone mineral density based on NHANES 2011–2018. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 8638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| N (%)/ Mean ± SD | Mean (SE) | 95%CI for Mean | Regression β | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender, n (%) | |||||

| Male | 19,893 (47.52) | 45.77 (0.068) | 45.63, 45.90 | ref | |

| Female | 21,966 (52.48) | 44.80 (0.066) | 44.67, 44.93 | 1.16 | <0.001 *** |

| Age, mean ± SD | 74.13 ± 6.66 | 45.26 (0.047) | 45.16, 45.35 | −0.36 | <0.001 *** |

| Marital status, n (%) | |||||

| Single | 8707 (20.80) | 42.61 (0.115) | 42.38, 42.83 | ref | |

| Married | 33,152 (79.20) | 45.95 (0.051) | 45.85, 46.05 | 3.35 | <0.001 *** |

| Residence, n (%) | |||||

| Urban | 25,553 (61.05) | 45.89 (0.060) | 45.78, 46.01 | ref | |

| Rural | 16,306 (38.95) | 44.26 (0.077) | 44.11, 44.41 | −1.63 | <0.001 *** |

| Education, n (%) | |||||

| Primary school and lower | 22,475 (53.69) | 43.83 (0.067) | 43.70, 43.95 | ref | |

| Junior high school | 10,402 (24.85) | 46.98 (0.089) | 46.80, 47.15 | 2.93 | <0.001 *** |

| Senior high school or technical secondary school | 6279 (15.00) | 46.76 (0.117) | 46.53, 46.99 | 3.15 | <0.001 *** |

| College degree and above | 2703 (6.46) | 47.06 (0.176) | 46.70, 47.39 | 3.22 | <0.001 *** |

| Monthly income, Chinese Yuan, n (%) | |||||

| <3000 | 25,443 (60.78) | 44.55 (0.062) | 44.43, 44.67 | ref | |

| 3000~6000 | 12,959 (30.96) | 46.43 (0.083) | 46.26, 46.59 | 1.87 | <0.001 *** |

| 6000~10,000 | 2896 (6.92) | 46.46 (0.171) | 46.13, 46.80 | 1.91 | <0.001 *** |

| ≥10,000 | 561 (1.34) | 44.04 (0.458) | 43.14, 44.94 | 0.30 | 0.219 |

| Smoking status, n (%) | |||||

| No | 36,566 (87.36) | 45.14 (0.051) | 45.04, 45.24 | ref | |

| Yes | 5293 (12.64) | 46.07 (0.132) | 45.81, 46.33 | 0.93 | <0.001 *** |

| Alcohol status, n (%) | |||||

| No | 38,840 (92.79) | 45.14 (0.049) | 45.04, 45.24 | ref | |

| Yes | 3019 (7.21) | 46.75 (0.176) | 46.41, 47.09 | 1.61 | <0.001 *** |

| Chronic disease Status, n (%) | |||||

| Without chronic disease | 9781 (23.37) | 44.20 (0.096) | 44.01, 44.39 | ref | |

| With chronic disease | 32,078 (76.63) | 45.27 (0.055) | 45.17, 45.38 | −0.002 | 0.799 |

| Depression Status, | |||||

| No Depressive Symptoms | 26,075 (62.29) | 49.23 (0.045) | 49.14, 49.32 | ref | |

| Mild Major Depressive Symptoms | 12,405 (29.64) | 40.55 (0.079) | 40.39, 40.71 | −8.68 | <0.001 *** |

| Moderate Depressive Symptoms | 2524 (6.03) | 33.40 (0.168) | 33.07, 33.73 | −15.83 | <0.001 *** |

| Moderate-Severe Major Depressive Symptoms | 638 (1.52) | 28.84 (0.376) | 28.10, 29.58 | −20.38 | <0.001 *** |

| Severe Major Depressive Symptoms | 217 (0.52) | 23.37 (0.796) | 21.80, 24.94 | −25.86 | <0.001 *** |

| BMI | 23.69 ± 3.46 | - | - | 0.16 | <0.001 *** |

| PASE | 100.58 ± 65.81 | - | - | 0.04 | <0.001 *** |

| MNA | 24.26 ± 3.17 | - | - | 0.54 | <0.001 *** |

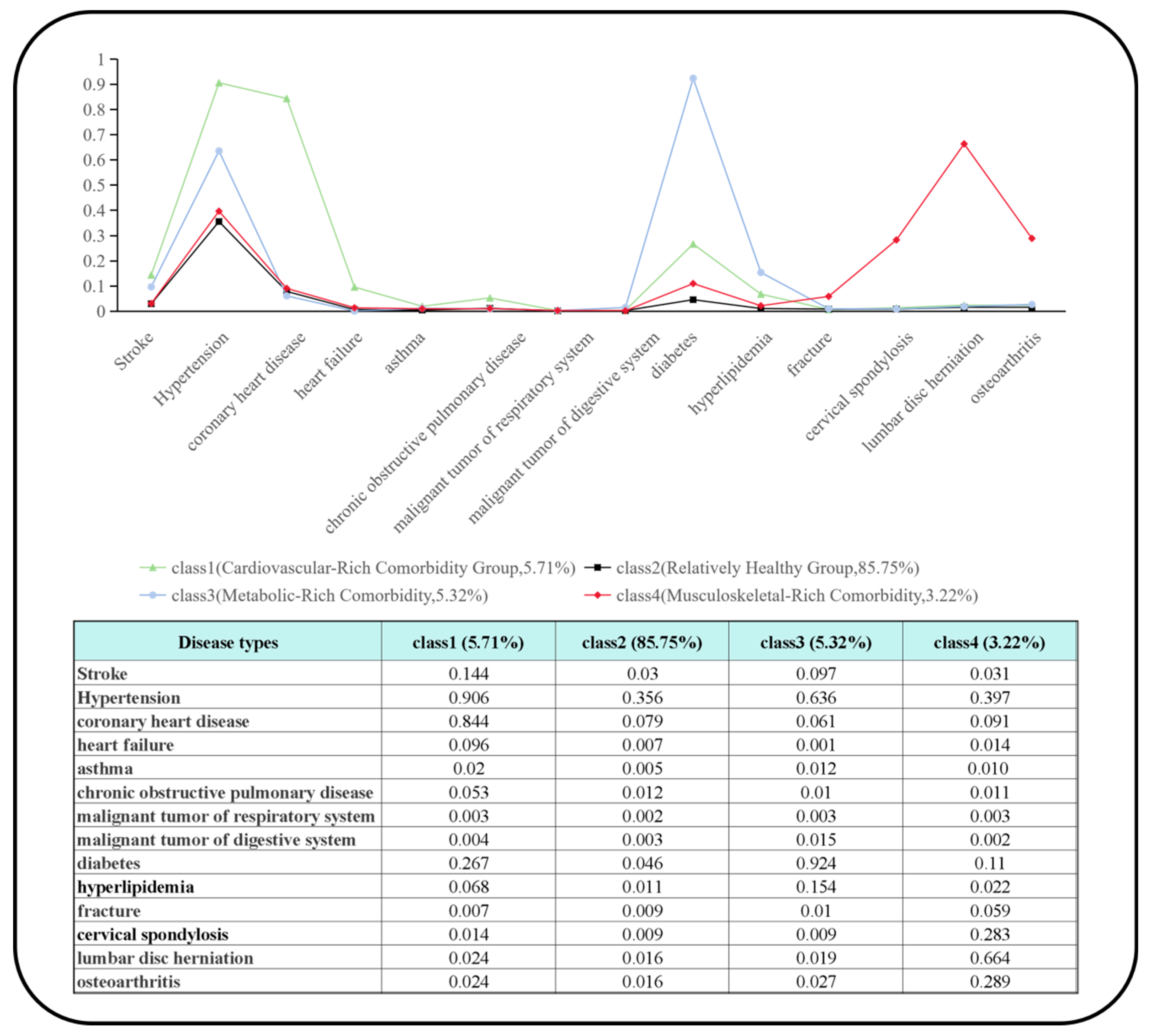

| Number of Classes | AIC | BIC | ABIC | LMRT | BLRT | Entropy | Relative Frequence of Smallest Class (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 190,552.220 | 190,673.209 | 190,628.717 | - | - | - | - |

| 2 | 187,887.798 | 188,138.418 | 188,046.256 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.630 | 13.91 |

| 3 | 186,830.499 | 187,210.750 | 187,070.918 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.728 | 2.27 |

| 4 | 186,155.710 | 186,665.591 | 186,478.089 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.833 | 3.22 |

| 5 | 185,941.510 | 186,581.022 | 186,345.850 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.587 | 2.12 |

| 6 | 185,863.059 | 186,632.203 | 186,349.360 | 0.0002 | 0.0000 | 0.593 | 1.06 |

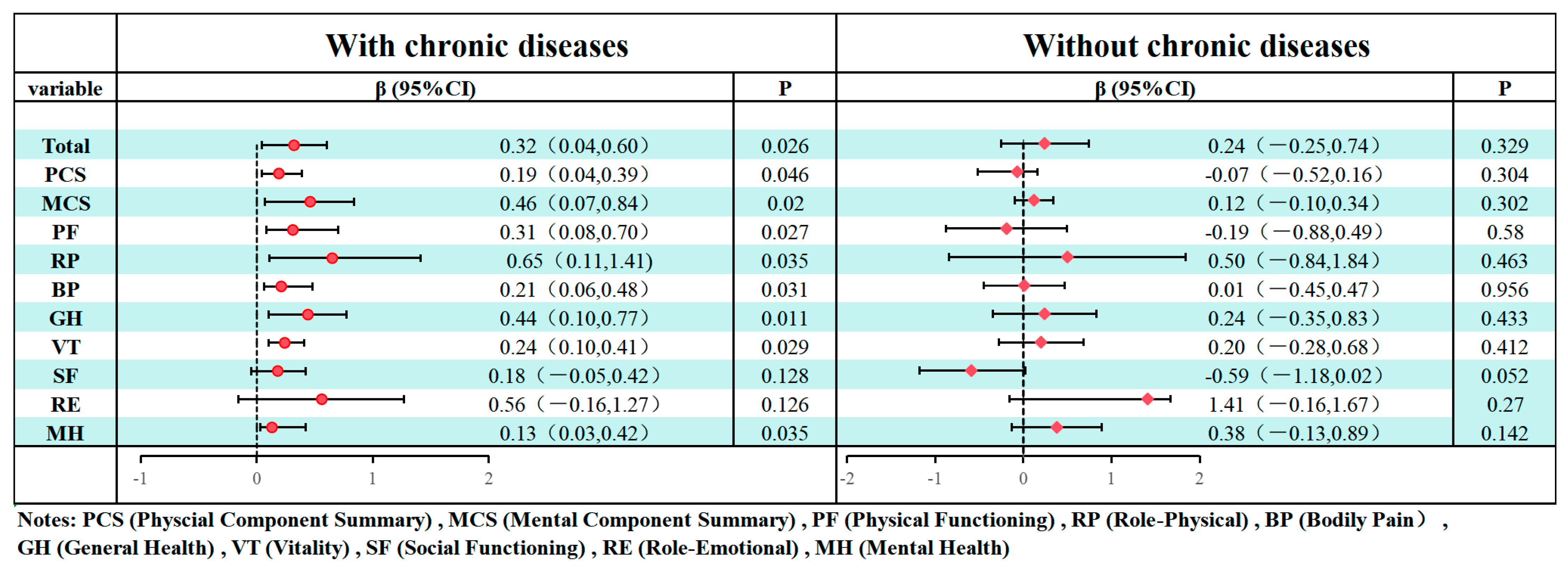

| Comorbidity Patterns | β (95% CI) | p-Value | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cardiovascular-Rich Comorbidity Group (class 1) | 0.58 [0.16, 1.01] | 0.025 | * |

| Relatively Healthy Group (class 2) | 0.18 [−0.16, 0.52] | 0.270 | - |

| Metabolic-Rich Comorbidity Group (class 3) | 0.76 [0.28, 1.24] | 0.022 | * |

| Musculoskeletal-Rich Comorbidity Group (class 4) | 1.01 [0.22, 1.74] | 0.021 | * |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Qiu, G.; Huang, Z.; Zhao, X.; Ren, J.; Yang, B.; Wang, Z.; Zhu, H.; Lin, S.; Sun, L.; Wang, Y.; et al. Association Between Mini Nutritional Assessment and Health Related Quality of Life in Chinese Older Adults: A Large Cross-Sectional Study Stratified by Chronic Disease Status. Nutrients 2025, 17, 3510. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17223510

Qiu G, Huang Z, Zhao X, Ren J, Yang B, Wang Z, Zhu H, Lin S, Sun L, Wang Y, et al. Association Between Mini Nutritional Assessment and Health Related Quality of Life in Chinese Older Adults: A Large Cross-Sectional Study Stratified by Chronic Disease Status. Nutrients. 2025; 17(22):3510. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17223510

Chicago/Turabian StyleQiu, Gonghang, Zishuo Huang, Xuelan Zhao, Jiaoqi Ren, Borui Yang, Ziyi Wang, Hongfei Zhu, Shuna Lin, Liang Sun, Ying Wang, and et al. 2025. "Association Between Mini Nutritional Assessment and Health Related Quality of Life in Chinese Older Adults: A Large Cross-Sectional Study Stratified by Chronic Disease Status" Nutrients 17, no. 22: 3510. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17223510

APA StyleQiu, G., Huang, Z., Zhao, X., Ren, J., Yang, B., Wang, Z., Zhu, H., Lin, S., Sun, L., Wang, Y., & Zhou, H. (2025). Association Between Mini Nutritional Assessment and Health Related Quality of Life in Chinese Older Adults: A Large Cross-Sectional Study Stratified by Chronic Disease Status. Nutrients, 17(22), 3510. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17223510