The Emerging Role of Citrulline and Theanine in Health and Disease: A Comprehensive Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Discovery of L-Citrulline and L-Theanine

2.1. Natural Occurrence of L-Citrulline

2.2. Natural Occurrence of L-Theanine

3. Metabolism of L-Citrulline and L-Theanine

3.1. Metabolism of L-Citrulline

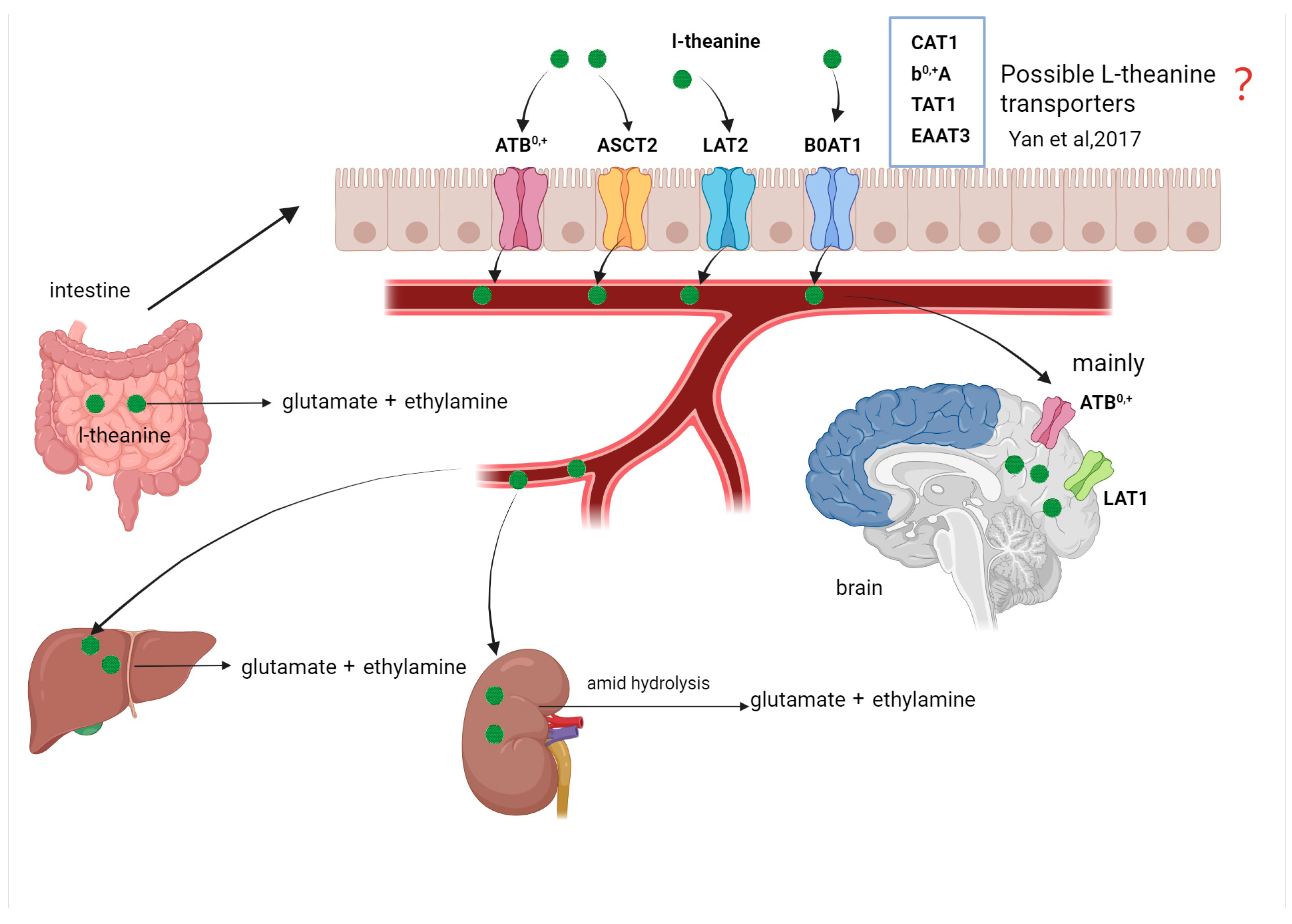

3.2. Metabolism of L-Theanine

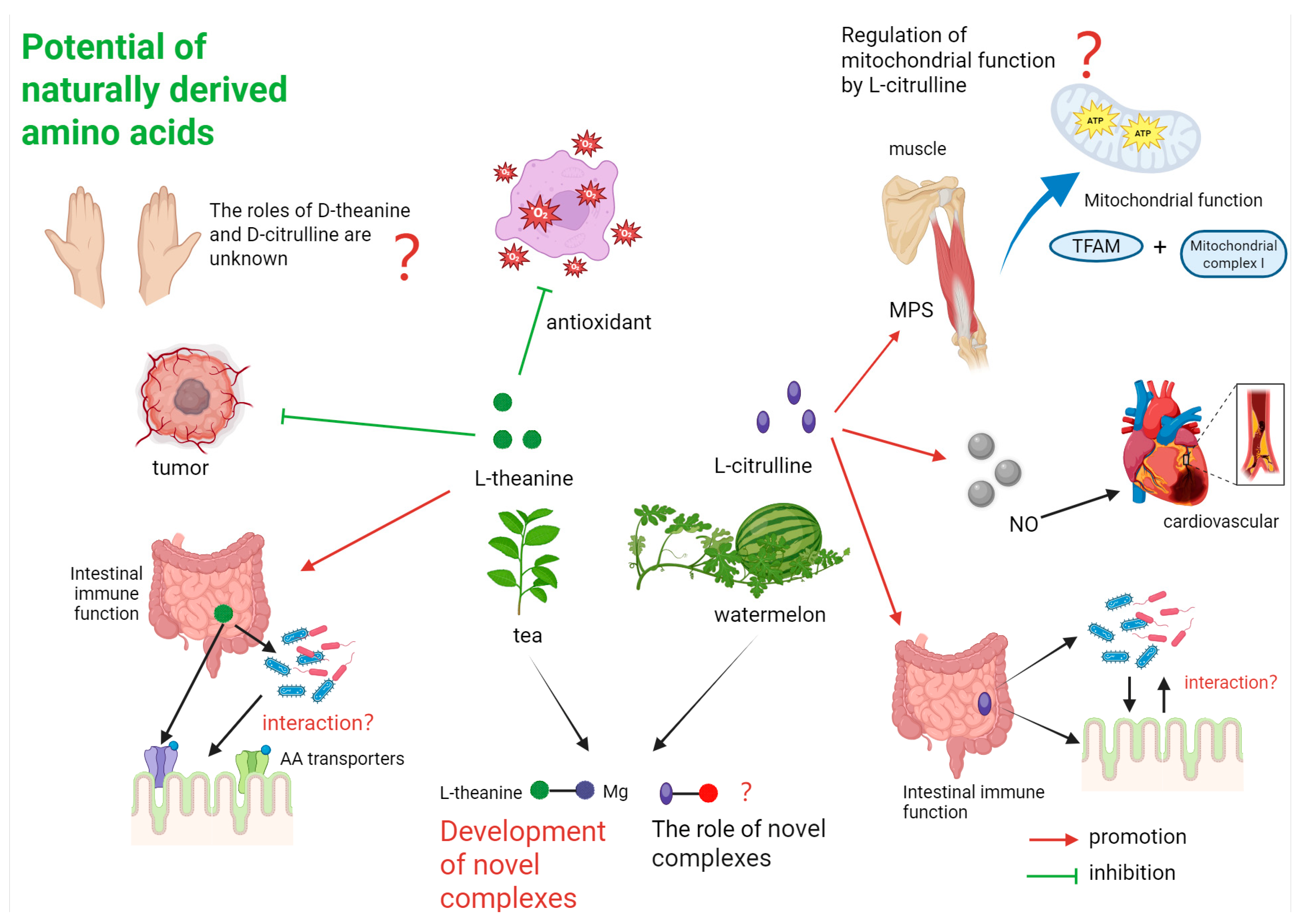

4. The Beneficial Effects of L-Citrulline

4.1. L-Citrulline—An Excellent Substitute for Arginine in the Treatment of Endothelial Cell Dysfunction

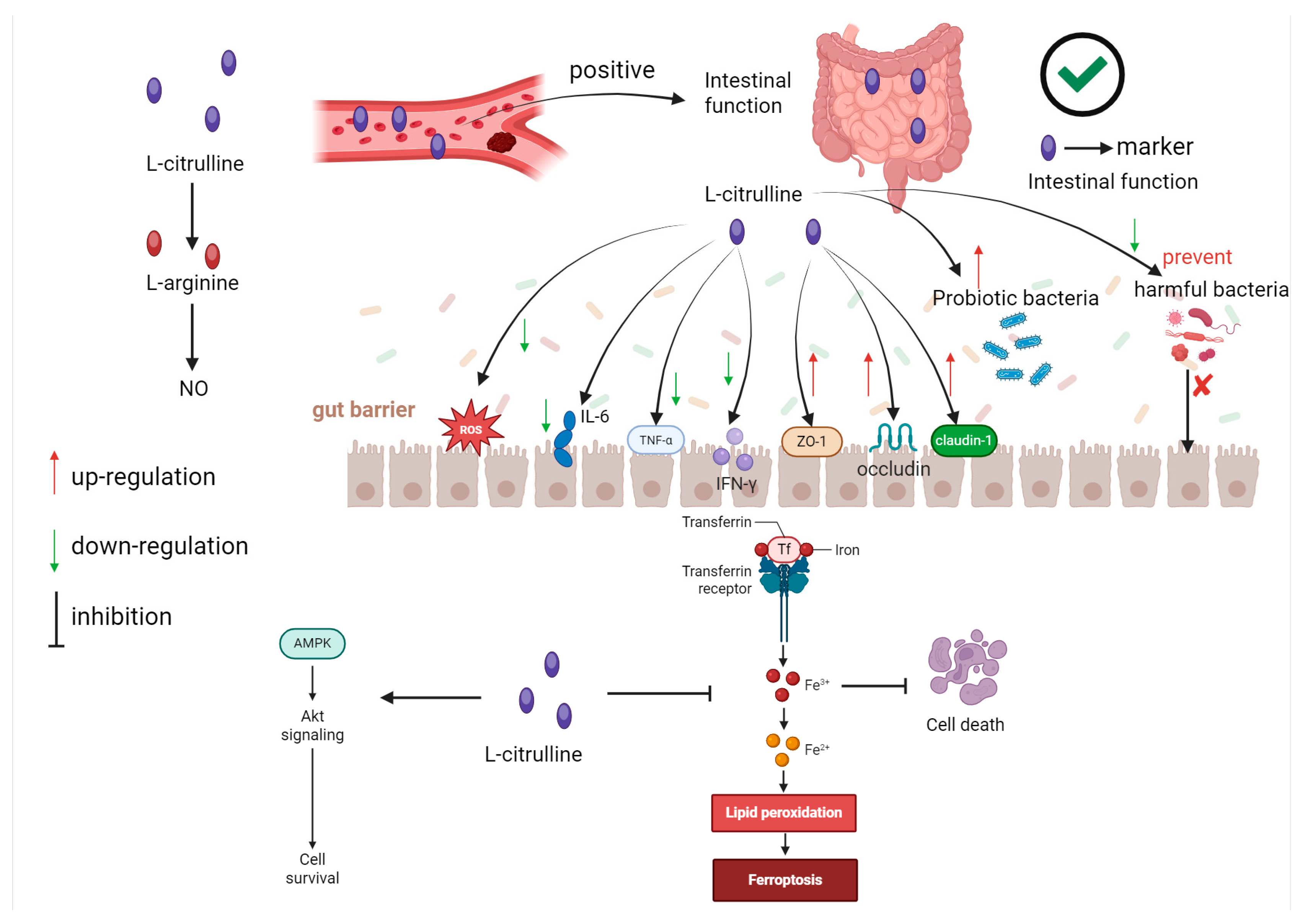

4.2. The Role of L-Citrulline in Regulating Intestinal Immunity

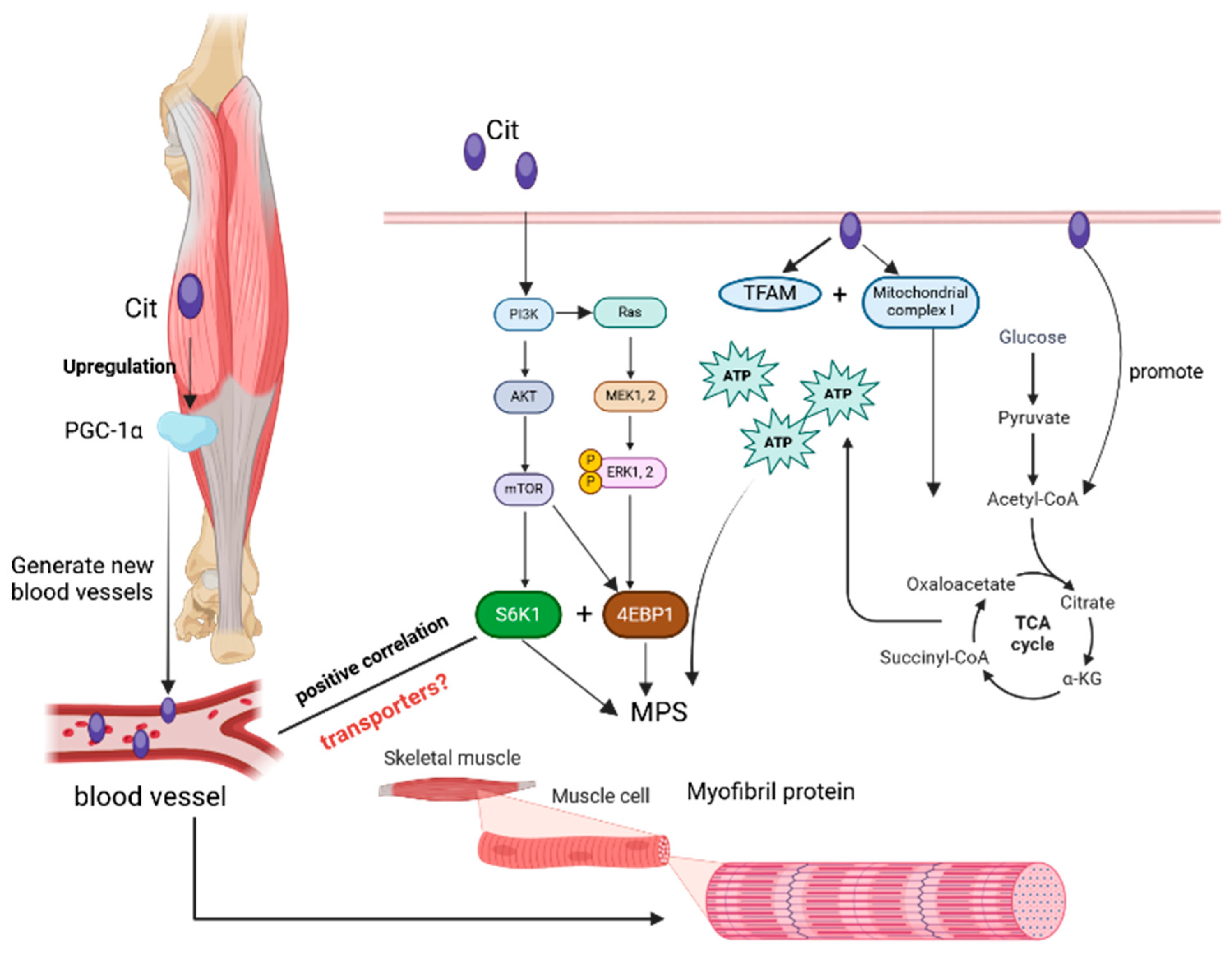

4.3. The Role of L-Citrulline in Regulating Muscle Protein Synthesis

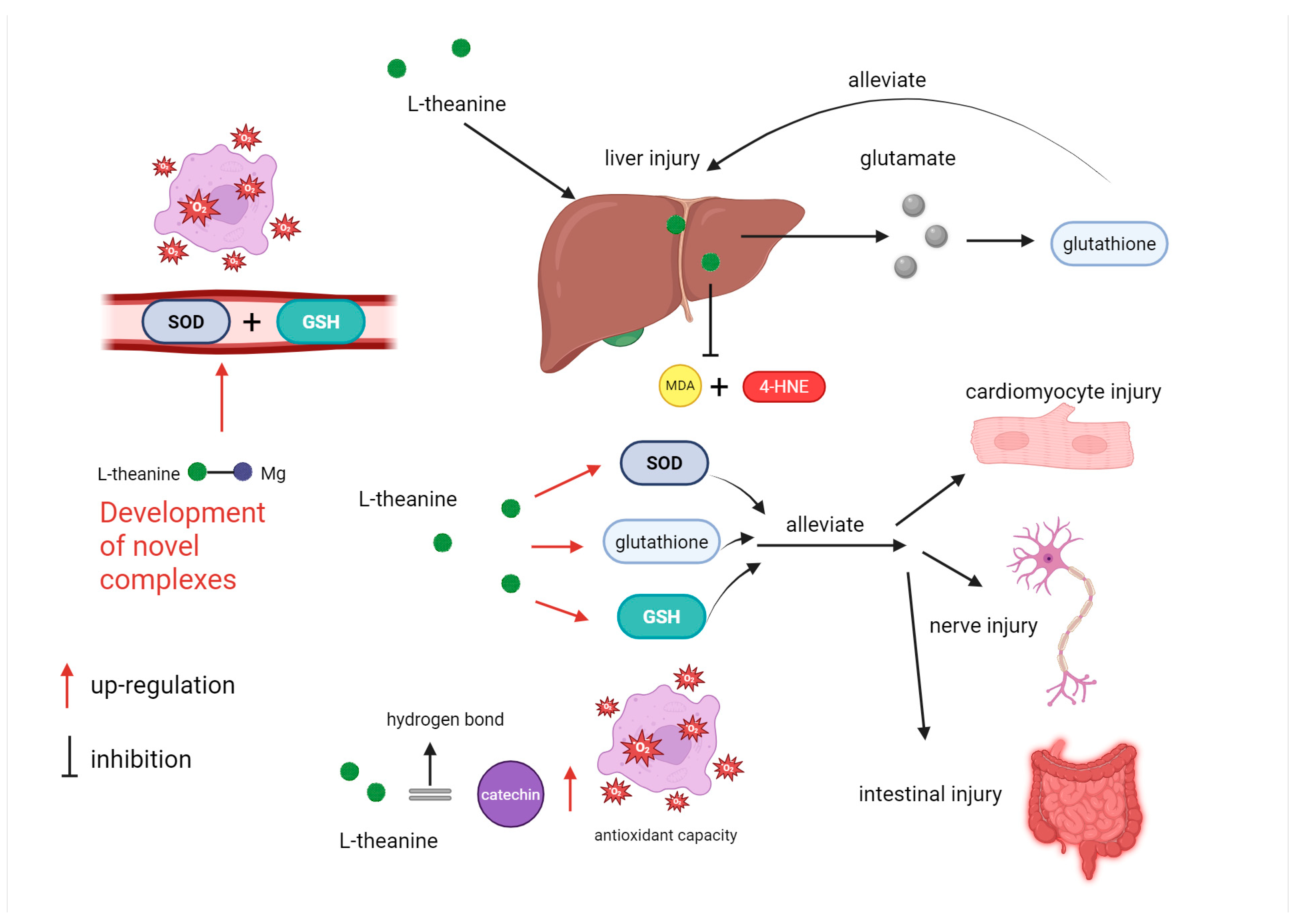

5. The Beneficial Effects of L-Theanine

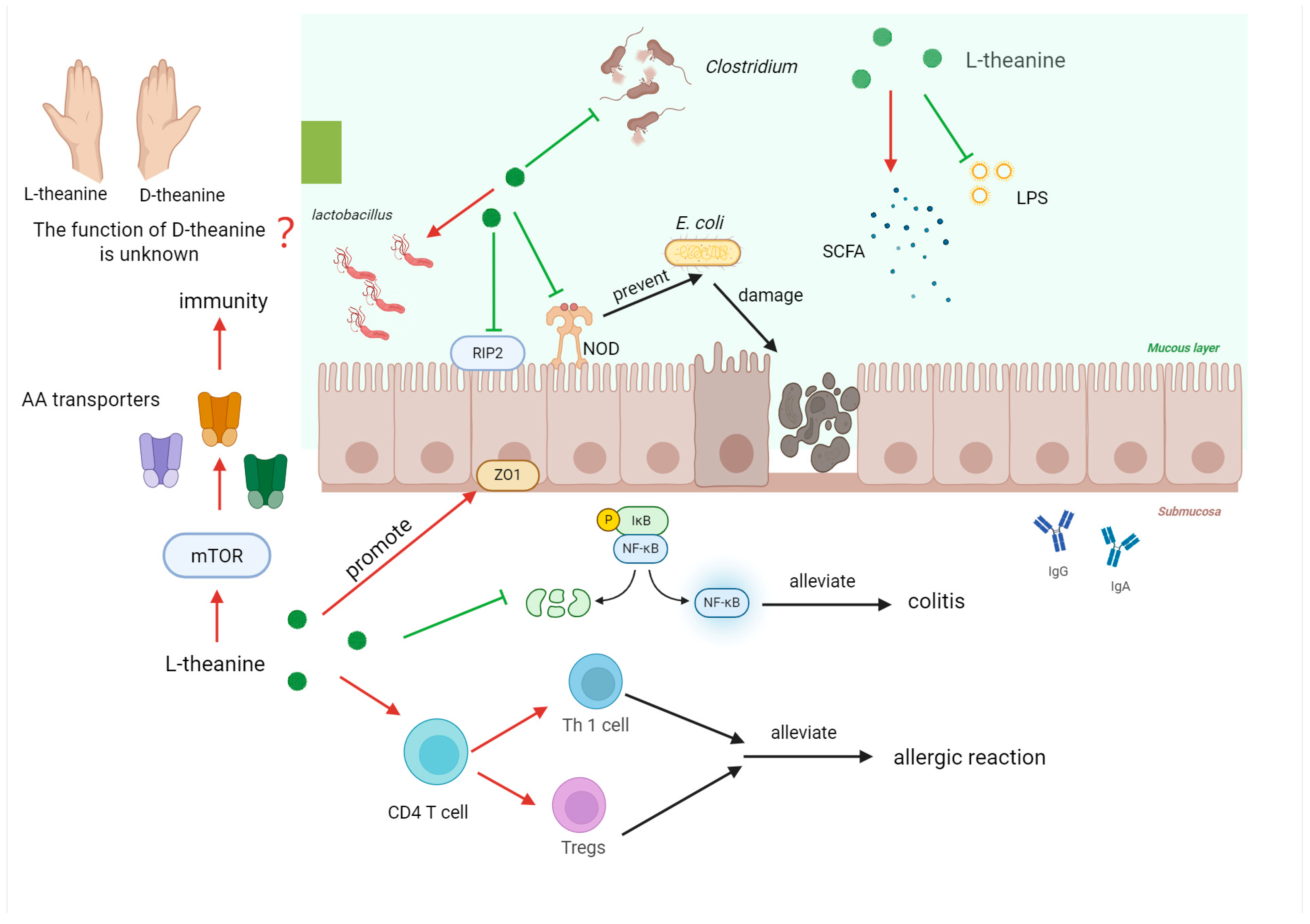

5.1. The Role of L-Theanine in Regulating Intestinal Immunity

5.2. The Role of L-Theanine in Inhibiting Tumors

5.3. The Antioxidant Function of L-Theanine

6. Limitations, Potential Side Effects, and Considerations for Use

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Davidova, I.; Ruban, O.; Herbina, N. Pharmacological activity of amino acids and prospects for the creation of drugs based on them. Ann. Mechnikov’s Inst. 2022, 4, 11–31. [Google Scholar]

- He, W.; Connolly, E.D.; Cross, H.R.; Wu, G. Dietary protein and amino acid intakes for mitigating sarcopenia in humans. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2024, 65, 2538–2561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, B.; Pearce, E.L. Amino assets: How amino acids support immunity. Cell Metab. 2020, 32, 154–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGarrah, R.W.; White, P.J. Branched-chain amino acids in cardiovascular disease. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2023, 20, 77–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, R.; Zou, Q.; Zhao, L.; Liu, Y.; Xing, R.; Yan, X. Amino-acid-encoded supramolecular photothermal nanomedicine for enhanced cancer therapy. Adv. Mater. 2022, 34, 2200139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, H.-C.; Han, J.-M. Amino acid metabolism in cancer drug resistance. Cells 2022, 11, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Y.; Wu, G. Nutritionally essential amino acids. Adv. Nutr. 2018, 9, 849–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, A.; Han, J.; Nakano, A.; Konno, H.; Moriwaki, H.; Abe, H.; Izawa, K.; Soloshonok, V.A. New pharmaceuticals approved by FDA in 2020: Small-molecule drugs derived from amino acids and related compounds. Chirality 2022, 34, 86–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bongioanni, A.; Bueno, M.S.; Mezzano, B.A.; Longhi, M.R.; Garnero, C. Amino acids and its pharmaceutical applications: A mini review. Int. J. Pharm. 2022, 613, 121375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G. Amino Acids: Biochemistry and Nutrition; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Papadia, C.; Osowska, S.; Cynober, L.; Forbes, A. Citrulline in health and disease. Review on human studies. Clin. Nutr. 2018, 37, 1823–1828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Kang, J.; Zhu, H.; Wang, K.; Han, Z.; Wang, L.; Liu, J.; Wu, Y.; He, P.; Tu, Y. L-theanine and immunity: A review. Molecules 2023, 28, 3846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguayo, E.; Martínez-Sánchez, A.; Fernández-Lobato, B.; Alacid, F. L-Citrulline: A non-essential amino acid with important roles in human health. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 3293. [Google Scholar]

- Berger, M.; Gray, J.A.; Roth, B.L. The expanded biology of serotonin. Annu. Rev. Med. 2009, 60, 355–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uyanga, V.A.; Oke, E.O.; Amevor, F.K.; Zhao, J.; Wang, X.; Jiao, H.; Onagbesan, O.M.; Lin, H. Functional roles of taurine, L-theanine, L-citrulline, and betaine during heat stress in poultry. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 2022, 13, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koga, Y. Study report on the constituents of squeezed watermelon. J. Chem. Soc. Tokyo 1914, 35, 519. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, A.R.; Webber, C.L.; Fish, W.W.; Wehner, T.C.; King, S.; Perkins-Veazie, P. L-citrulline levels in watermelon cultigens tested in two environments. HortScience 2011, 46, 1572–1575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarazona-Díaz, M.P.; Viegas, J.; Moldao-Martins, M.; Aguayo, E. Bioactive compounds from flesh and by-product of fresh-cut watermelon cultivars. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2011, 91, 805–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valle-Vargas, M.F.; Durán-Barón, R.; Quintero-Gamero, G.; Valera, R. Caracterización fisicoquímica, químico proximal, compuestos bioactivos y capacidad antioxidante de pulpa y corteza de sandía (Citrullus lanatus). Inf. Tecnol. 2020, 31, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rimando, A.M.; Perkins-Veazie, P.M. Determination of citrulline in watermelon rind. J. Chromatogr. A 2005, 1078, 196–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fragkos, K.C.; Forbes, A. Citrulline as a marker of intestinal function and absorption in clinical settings: A systematic review and meta-analysis. United Eur. Gastroenterol. J. 2018, 6, 181–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durán, R.; Villegas, M.E.; Nieves, I. Caracterización y extracción de citrulina de la corteza de la sandía (Citrullus lanatus “thunb”) consumida en Valledupar [Characterization and extraction of citrulline of the watermelon rind (Citrullus lanatus” thunb”) consumed in Valledupar]. Temas Agrar. 2017, 22, 61. [Google Scholar]

- Mandel, H.; Levy, N.; Izkovitch, S.; Korman, S. Elevated plasma citrulline and arginine due to consumption of Citrullus vulgaris (watermelon). J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 2005, 28, 467–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Y.; Liu, Z.; Liu, Z.; Feng, Z.; Zhang, L.; Wan, X.; Yang, X. Identification of d-amino acids in tea leaves. Food Chem. 2020, 317, 126428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashihara, H. Occurrence, biosynthesis and metabolism of theanine (γ-glutamyl-L-ethylamide) in plants: A comprehensive review. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2015, 10, 1934578X1501000525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boros, K.; Jedlinszki, N.; Csupor, D. Theanine and caffeine content of infusions prepared from commercial tea samples. Pharmacogn. Mag. 2016, 12, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.-Y.; Liu, H.-Y.; Wu, D.-T.; Kenaan, A.; Geng, F.; Li, H.-B.; Gunaratne, A.; Li, H.; Gan, R.-Y. L-theanine: A unique functional amino acid in tea (Camellia sinensis L.) with multiple health benefits and food applications. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 853846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, W.-W.; Ogita, S.; Ashihara, H. Distribution and biosynthesis of theanine in Theaceae plants. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2010, 48, 70–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiori, J.; Pasquini, B.; Caprini, C.; Orlandini, S.; Furlanetto, S.; Gotti, R. Chiral analysis of theanine and catechin in characterization of green tea by cyclodextrin-modified micellar electrokinetic chromatography and high performance liquid chromatography. J. Chromatogr. A 2018, 1562, 115–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Z.; Wang, Z.; Yuan, H.; He, N. From tea leaves to factories: A review of research progress in L-theanine biosynthesis and production. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2021, 69, 1187–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y.; Xiao, W.; Chen, L.; Liu, Q.; Liu, Z.; Gong, Z. In vivo antioxidative effects of l-theanine in the presence or absence of Escherichia coli-induced oxidative stress. J. Funct. Foods 2016, 24, 527–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheid, L.; Ellinger, S.; Alteheld, B.; Herholz, H.; Ellinger, J.; Henn, T.; Helfrich, H.-P.; Stehle, P. Kinetics of ʟ-Theanine Uptake and Metabolism in Healthy Participants Are Comparable after Ingestion of ʟ-Theanine via Capsules and Green Tea, 4. J. Nutr. 2012, 142, 2091–2096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.-Y.; Zhao, C.-N.; Cao, S.-Y.; Tang, G.-Y.; Gan, R.-Y.; Li, H.-B. Effects and mechanisms of tea for the prevention and management of cancers: An updated review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2020, 60, 1693–1705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, J.; Zhao, X.; Tian, J.; Xue, R.; Luo, B.; Lv, J.; Gao, J.; Wang, M. Theanine attenuates hippocampus damage of rat cerebral ischemia-reperfusion injury by inhibiting HO-1 expression and activating ERK1/2 pathway. Life Sci. 2020, 241, 117160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranjha, M.M.A.N.; Shafique, B.; Batool, M.; Kowalczewski, P.Ł.; Shehzad, Q.; Usman, M.; Manzoor, M.F.; Zahra, S.M.; Yaqub, S.; Aadil, R.M. Nutritional and health potential of probiotics: A review. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 11204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Böhmer, C.; Bröer, A.; Munzinger, M.; Kowalczuk, S.; Rasko, J.E.; Lang, F.; Bröer, S. Characterization of mouse amino acid transporter B0AT1 (slc6a19). Biochem. J. 2005, 389, 745–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bröer, S.; Bröer, A. Amino acid homeostasis and signalling in mammalian cells and organisms. Biochem. J. 2017, 474, 1935–1963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitsuoka, K.; Shirasaka, Y.; Fukushi, A.; Sato, M.; Nakamura, T.; Nakanishi, T.; Tamai, I. Transport characteristics of L-citrulline in renal apical membrane of proximal tubular cells. Biopharm. Drug Dispos. 2009, 30, 126–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maric, S.; Restin, T.; Muff, J.L.; Camargo, S.M.; Guglielmetti, L.C.; Holland-Cunz, S.G.; Crenn, P.; Vuille-dit-Bille, R.N. Citrulline, biomarker of enterocyte functional mass and dietary supplement. Metabolism, transport, and current evidence for clinical use. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwedhelm, E.; Maas, R.; Freese, R.; Jung, D.; Lukacs, Z.; Jambrecina, A.; Spickler, W.; Schulze, F.; Böger, R.H. Pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic properties of oral L-citrulline and L-arginine: Impact on nitric oxide metabolism. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2008, 65, 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moinard, C.; Nicolis, I.; Neveux, N.; Darquy, S.; Bénazeth, S.; Cynober, L. Dose-ranging effects of citrulline administration on plasma amino acids and hormonal patterns in healthy subjects: The Citrudose pharmacokinetic study. Br. J. Nutr. 2008, 99, 855–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Windmueller, H.G. Glutamine utilization by the small intestine. Adv. Enzymol. Relat. Areas Mol. Biol. 1982, 53, 201–237. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Tyszko, M.; Lemańska-Perek, A.; Śmiechowicz, J.; Tomaszewska, P.; Biecek, P.; Gozdzik, W.; Adamik, B. Citrulline, intestinal fatty acid-binding protein and the acute gastrointestinal injury score as predictors of gastrointestinal failure in patients with sepsis and septic shock. Nutrients 2023, 15, 2100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kao, C.; Hsu, J.; Bandi, V.; Jahoor, F. Alterations in glutamine metabolism and its conversion to citrulline in sepsis. Am. J. Physiol.-Endocrinol. Metab. 2013, 304, E1359–E1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Husson, A.; Brasse-Lagnel, C.; Fairand, A.; Renouf, S.; Lavoinne, A. Argininosuccinate synthetase from the urea cycle to the citrulline–NO cycle. Eur. J. Biochem. 2003, 270, 1887–1899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allerton, T.D.; Proctor, D.N.; Stephens, J.M.; Dugas, T.R.; Spielmann, G.; Irving, B.A. l-Citrulline supplementation: Impact on cardiometabolic health. Nutrients 2018, 10, 921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morita, M.; Hayashi, T.; Ochiai, M.; Maeda, M.; Yamaguchi, T.; Ina, K.; Kuzuya, M. Oral supplementation with a combination of L-citrulline and L-arginine rapidly increases plasma L-arginine concentration and enhances NO bioavailability. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2014, 454, 53–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cynober, L.A. Metabolic & Therapeutic Aspects of Amino Acids in Clinical Nutrition; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Pegg, A.E. Functions of polyamines in mammals. J. Biol. Chem. 2016, 291, 14904–14912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madeo, F.; Eisenberg, T.; Pietrocola, F.; Kroemer, G. Spermidine in health and disease. Science 2018, 359, eaan2788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris Jr, S.M. Arginine metabolism revisited. J. Nutr. 2016, 146, 2579S–2586S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeed, M.; Khan, M.S.; Kamboh, A.A.; Alagawany, M.; Khafaga, A.F.; Noreldin, A.E.; Qumar, M.; Safdar, M.; Hussain, M.; Abd El-Hack, M.E. L-theanine: An astounding sui generis amino acid in poultry nutrition. Poult. Sci. 2020, 99, 5625–5636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vuong, Q.V.; Bowyer, M.C.; Roach, P.D. L-Theanine: Properties, synthesis and isolation from tea. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2011, 91, 1931–1939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becquet, P.; Vazquez-Anon, M.; Mercier, Y.; Batonon-Alavo, D.I.; Yan, F.; Wedekind, K.; Mahmood, T. Absorption of methionine sources in animals—Is there more to know? Anim. Nutr. 2023, 12, 159–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Q.; Tong, H.; Tang, S.; Tan, Z.; Han, X.; Zhou, C. L-Theanine administration modulates the absorption of dietary nutrients and expression of transporters and receptors in the intestinal mucosa of rats. BioMed Res. Int. 2017, 2017, 9747256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitaoka, S.; Hayashi, H.; Yokogoshi, H.; Suzuki, Y. Transmural potential changes associated with the in vitro absorption of theanine in the guinea pig intestine. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 1996, 60, 1768–1771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuge, H.; Sano, S.; Hayakawa, T.; Kakuda, T.; Unno, T. Theanine, γ-glutamylethylamide, is metabolized by renal phosphate-independent glutaminase. Biochim. Biophys. Acta BBA-Gen. Subj. 2003, 1620, 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ninomiya, T.; Kanzaki, N.; Hirakawa, Y.; Yoshinari, M.; Higashioka, M.; Honda, T.; Shibata, M.; Sakata, S.; Yoshida, D.; Teramoto, T. Serum ethylamine levels as an indicator of L-theanine consumption and the risk of type 2 diabetes in a general Japanese population: The Hisayama study. Diabetes Care 2019, 42, 1234–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haybar, H.; Shahrabi, S.; Rezaeeyan, H.; Shirzad, R.; Saki, N. Endothelial cells: From dysfunction mechanism to pharmacological effect in cardiovascular disease. Cardiovasc. Toxicol. 2019, 19, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ambrosino, P.; Bachetti, T.; D’Anna, S.E.; Galloway, B.; Bianco, A.; D’Agnano, V.; Papa, A.; Motta, A.; Perrotta, F.; Maniscalco, M. Mechanisms and clinical implications of endothelial dysfunction in arterial hypertension. J. Cardiovasc. Dev. Dis. 2022, 9, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shatanawi, A.; Momani, M.S.; Al-Aqtash, R.; Hamdan, M.H.; Gharaibeh, M.N. L-Citrulline supplementation increases plasma nitric oxide levels and reduces arginase activity in patients with type 2 diabetes. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 584669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szlas, A.; Kurek, J.M.; Krejpcio, Z. The potential of L-arginine in prevention and treatment of disturbed carbohydrate and lipid metabolism—A review. Nutrients 2022, 14, 961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Jasmi, F.; Al Zaabi, N.; Al-Thihli, K.; Al Teneiji, A.M.; Hertecant, J.; El-Hattab, A.W. Endothelial dysfunction and the effect of arginine and citrulline supplementation in children and adolescents with mitochondrial diseases. J. Cent. Nerv. Syst. Dis. 2020, 12, 1179573520909377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smeets, E.T.; Mensink, R.P.; Joris, P.J. Effects of l-citrulline supplementation and watermelon consumption on longer-term and postprandial vascular function and cardiometabolic risk markers: A meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials in adults. Br. J. Nutr. 2022, 128, 1758–1770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, S.M., Jr. Regulation of arginine availability and its impact on NO synthesis. In Nitric Oxide; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2000; pp. 187–197. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, R.W.; Fernstrom, J.D.; Thompson, J.; Morris Jr, S.M.; Kuller, L.H. Biochemical responses of healthy subjects during dietary supplementation with L-arginine. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2004, 15, 534–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero, M.J.; Platt, D.H.; Caldwell, R.B.; Caldwell, R.W. Therapeutic use of citrulline in cardiovascular disease. Cardiovasc. Drug Rev. 2006, 24, 275–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, J.; Kumar, S.S.; Job, K.M.; Liu, X.; Fike, C.D.; Sherwin, C.M. Therapeutic potential of citrulline as an arginine supplement: A clinical pharmacology review. Pediatr. Drugs 2020, 22, 279–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dillon, K.N.; Kang, Y.; Maharaj, A.; Martinez, M.A.; Fischer, S.M.; Figueroa, A. L-Citrulline supplementation attenuates aortic pressure and pressure waves during metaboreflex activation in postmenopausal women. Br. J. Nutr. 2024, 131, 474–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimble, G.K. Adverse gastrointestinal effects of arginine and related amino acids. J. Nutr. 2007, 137, 1693S–1701S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cylwik, D.; Mogielnicki, A.; Kramkowski, K.; Stokowski, J.; Buczko, W. Antithrombotic effect of L-arginine in hypertensive rats. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2004, 55, 563–574. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Azizi, S.; Mahdavi, R.; Vaghef-Mehrabany, E.; Maleki, V.; Karamzad, N.; Ebrahimi-Mameghani, M. Potential roles of Citrulline and watermelon extract on metabolic and inflammatory variables in diabetes mellitus, current evidence and future directions: A systematic review. Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol. 2020, 47, 187–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.-Y.; Guo, Y.-C.; Zhou, H.-F.; Yue, T.-T.; Wang, F.-X.; Sun, F.; Wang, W.-Z. Arginine metabolism regulates the pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease. Nutr. Rev. 2023, 81, 578–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ho, S.W.; El-Nezami, H.; Corke, H.; Ho, C.S.; Shah, N.P. L-citrulline enriched fermented milk with Lactobacillus helveticus attenuates dextran sulfate sodium (DSS) induced colitis in mice. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2022, 99, 108858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burton-Freeman, B.; Freeman, M.; Zhang, X.; Sandhu, A.; Edirisinghe, I. Watermelon and L-citrulline in cardio-metabolic health: Review of the evidence 2000–2020. Curr. Atheroscler. Rep. 2021, 23, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikeda, Y.; Young, L.; Scalia, R.; Lefer, A.M. Cardioprotective effects of citrulline in ischemia/reperfusion injury via a non-nitric oxide-mediated mechanism. Methods Find. Exp. Clin. Pharmacol. 2000, 22, 563–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malinowski, B.; Wiciński, M.; Sokołowska, M.M.; Hill, N.A.; Szambelan, M. The rundown of dietary supplements and their effects on inflammatory bowel disease—A review. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, F.C.; Patangia, D.; Grimaud, G.; Lavelle, A.; Dempsey, E.M.; Ross, R.P.; Stanton, C. The interplay between diet and the gut microbiome: Implications for health and disease. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2024, 22, 671–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dey, N.; Bhattacharjee, S. Accumulation of polyphenolic compounds and osmolytes under dehydration stress and their implication in redox regulation in four indigenous aromatic rice cultivars. Rice Sci. 2020, 27, 329–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uyanga, V.A.; Amevor, F.K.; Liu, M.; Cui, Z.; Zhao, X.; Lin, H. Potential implications of citrulline and quercetin on gut functioning of monogastric animals and humans: A comprehensive review. Nutrients 2021, 13, 3782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaore, S.N.; Kaore, N.M. Citrulline: Pharmacological perspectives and role as a biomarker in diseases and toxicities. In Biomarkers in Toxicology; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2014; pp. 883–905. [Google Scholar]

- van de Poll, M.C.; Siroen, M.P.; van Leeuwen, P.A.; Soeters, P.B.; Melis, G.C.; Boelens, P.G.; Deutz, N.E.; Dejong, C.H. Interorgan amino acid exchange in humans: Consequences for arginine and citrulline metabolism. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2007, 85, 167–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G.; Meininger, C.J.; McNeal, C.J.; Bazer, F.W.; Rhoads, J.M. Role of L-arginine in nitric oxide synthesis and health in humans. In Amino Acids in Nutrition and Health: Amino Acids in Gene Expression, Metabolic Regulation, and Exercising Performance; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 167–187. [Google Scholar]

- Azeredo, R.; Machado, M.; Fontinha, F.; Fernández-Boo, S.; Conceição, L.E.; Dias, J.; Costas, B. Dietary arginine and citrulline supplementation modulates the immune condition and inflammatory response of European seabass. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2020, 106, 451–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, X.; Lu, Y.; Chen, H. New insights in intestinal oxidative stress damage and the health intervention effects of nutrients: A review. J. Funct. Foods 2020, 75, 104248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulines, J.M.U.; Lavilla, C.A., Jr.; Billacura, M.P.; Basalo, H.L.; Okechukwu, P.N. In vitro evaluation of the antiglycation and antioxidant potential of the dietary supplement L-citrulline. Sci. Pharm. Sci. 2023, 4, 46–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, Y.-W.; Lee, C.-H.; Lo, H.-C. Oral post-treatment supplementation with a combination of glutamine, citrulline, and antioxidant vitamins additively mitigates jejunal damage, oxidative stress, and inflammation in rats with intestinal ischemia and reperfusion. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0298334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D.; Gao, Y.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Deng, Y.; Niu, S.; Dai, H. L-Citrulline Ameliorates Iron Metabolism and Mitochondrial Quality Control via Activating AMPK Pathway in Intestine and Improves Microbiota in Mice with Iron Overload. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2024, 68, 2300723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, J.; Gan, M.; Xie, Z.; Zhou, C.; Jing, Y.; Li, M.; Liu, C.; Wang, M.; Dai, H.; Huang, Z. Effects of dietary L-Citrulline supplementation on growth performance, meat quality, and fecal microbial composition in finishing pigs. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1209389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, N.; Yan, F.; Wang, N.; Song, Y.; Yue, Y.; Guan, J.; Li, B.; Huo, G. Distinct gut microbiota and metabolite profiles induced by different feeding methods in healthy Chinese infants. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoghroban, H.S.; Ibrahim, F.M.; Nasef, N.A.; Saad, A.E. The impact of L-citrulline on murine intestinal cell integrity, immune response, and arginine metabolism in the face of Giardia lamblia infection. Acta Trop. 2023, 237, 106748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saad, A.E.; Zoghroban, H.S.; Ghanem, H.B.; El-Guindy, D.M.; Younis, S.S. The effects of L-citrulline adjunctive treatment of Toxoplasma gondii RH strain infection in a mouse model. Acta Trop. 2023, 239, 106830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Awasthi, V.; Chauhan, R.; Das, J. Administration of L-citrulline prevents Plasmodium growth by inhibiting/modulating T-regulatory cells during malaria pathogenesis. J. Vector Borne Dis. 2022, 59, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Y.; Shi, D.; Li, G.; Jiang, P. Citrulline depletion by ASS1 is required for proinflammatory macrophage activation and immune responses. Mol. Cell 2022, 82, 527–541. e527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valenzuela, P.L.; Morales, J.S.; Emanuele, E.; Pareja-Galeano, H.; Lucia, A. Supplements with purported effects on muscle mass and strength. Eur. J. Nutr. 2019, 58, 2983–3008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osowska, S.; Moinard, C.; Loï, C.; Neveux, N.; Cynober, L. Citrulline increases arginine pools and restores nitrogen balance after massive intestinal resection. Gut 2004, 53, 1781–1786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueroa, A.; Jaime, S.J.; Morita, M.; Gonzales, J.U.; Moinard, C. L-citrulline supports vascular and muscular benefits of exercise training in older adults. Exerc. Sport Sci. Rev. 2020, 48, 133–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouillanne, O.; Melchior, J.-C.; Faure, C.; Paul, M.; Canouï-Poitrine, F.; Boirie, Y.; Chevenne, D.; Forasassi, C.; Guery, E.; Herbaud, S. Impact of 3-week citrulline supplementation on postprandial protein metabolism in malnourished older patients: The Ciproage randomized controlled trial. Clin. Nutr. 2019, 38, 564–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jourdan, M.; Nair, K.S.; Carter, R.E.; Schimke, J.; Ford, G.C.; Marc, J.; Aussel, C.; Cynober, L. Citrulline stimulates muscle protein synthesis in the post-absorptive state in healthy people fed a low-protein diet—A pilot study. Clin. Nutr. 2015, 34, 449–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuci, O.; Archambault, E.; Dodacki, A.; Nubret, E.; De Bandt, J.-P.; Cynober, L. Effect of citrulline on muscle protein turnover in an in vitro model of muscle catabolism. Nutrition 2020, 71, 110597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Plénier, S.; Goron, A.; Sotiropoulos, A.; Archambault, E.; Guihenneuc, C.; Walrand, S.; Salles, J.; Jourdan, M.; Neveux, N.; Cynober, L. Citrulline directly modulates muscle protein synthesis via the PI3K/MAPK/4E-BP1 pathway in a malnourished state: Evidence from in vivo, ex vivo, and in vitro studies. Am. J. Physiol.-Endocrinol. Metab. 2017, 312, E27–E36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goron, A.; Lamarche, F.; Blanchet, S.; Delangle, P.; Schlattner, U.; Fontaine, E.; Moinard, C. Citrulline stimulates muscle protein synthesis, by reallocating ATP consumption to muscle protein synthesis. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2019, 10, 919–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drummond, M.J.; Rasmussen, B.B. Leucine-enriched nutrients and the regulation of mammalian target of rapamycin signalling and human skeletal muscle protein synthesis. Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care 2008, 11, 222–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dodd, K.M.; Tee, A.R. Leucine and mTORC1: A complex relationship. Am. J. Physiol.-Endocrinol. Metab. 2012, 302, E1329–E1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ham, D.J.; Gleeson, B.G.; Chee, A.; Baum, D.M.; Caldow, M.K.; Lynch, G.S.; Koopman, R. L-Citrulline protects skeletal muscle cells from cachectic stimuli through an iNOS-dependent mechanism. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0141572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moinard, C.; Le Plenier, S.; Noirez, P.; Morio, B.; Bonnefont-Rousselot, D.; Kharchi, C.; Ferry, A.; Neveux, N.; Cynober, L.; Raynaud-Simon, A. Citrulline supplementation induces changes in body composition and limits age-related metabolic changes in healthy male rats. J. Nutr. 2015, 145, 1429–1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goron, A.; Lamarche, F.; Cunin, V.; Dubouchaud, H.; Hourdé, C.; Noirez, P.; Corne, C.; Couturier, K.; Sève, M.; Fontaine, E. Synergistic effects of citrulline supplementation and exercise on performance in male rats: Evidence for implication of protein and energy metabolisms. Clin. Sci. 2017, 131, 775–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Villareal, M.O.; Matsukawa, T.; Isoda, H. L-Citrulline supplementation-increased skeletal muscle PGC-1α expression is associated with exercise performance and increased skeletal muscle weight. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2018, 62, 1701043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, S.-Y.; Nie, Q.; Tai, H.-C.; Song, X.-L.; Tong, Y.-F.; Zhang, L.-J.-F.; Wu, X.-W.; Lin, Z.-H.; Zhang, Y.-Y.; Ye, D.-Y. Tea and tea drinking: China’s outstanding contributions to the mankind. Chin. Med. 2022, 17, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Z.; Lin, L.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, S.; Liu, A.; Chen, L.; Liu, Q.; Deng, Y.; Xiao, W. Immune-modulatory effects and mechanism of action of L-theanine on ETEC-induced immune-stressed mice via nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-like receptor signaling pathway. J. Funct. Foods 2019, 54, 32–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, Q.-Y.; Song, X.-Y.; Lin, L.; Gong, Z.-H.; Xu, W.; Xiao, W.-J. L-theanine modulates intestine-specific immunity by regulating the differentiation of CD4+ T cells in ovalbumin-sensitized mice. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2022, 70, 14851–14863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Chen, L.; Jia, G.; Zhao, H.; Liu, G.; Huang, Z. L-theanine improves intestinal barrier functions by increasing tight junction protein expression and attenuating inflammatory reaction in weaned piglets. J. Funct. Foods 2023, 100, 105400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Yao, X.; Ma, M.; Ding, Y.; Zhang, H.; He, X.; Song, Z. Protective effect of l-theanine against DSS-induced colitis by regulating the lipid metabolism and reducing inflammation via the NF-κB signaling pathway. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2021, 69, 14192–14203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, D.; Cai, M.; Wang, T.; Liu, T.; Huang, J.; Wang, Y.; Granato, D. Ameliorative effects of L-theanine on dextran sulfate sodium induced colitis in C57BL/6J mice are associated with the inhibition of inflammatory responses and attenuation of intestinal barrier disruption. Food Res. Int. 2020, 137, 109409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Luo, D.; Jia, G.; Zhao, H.; Liu, G.; Huang, Z. L-theanine attenuates porcine intestinal tight junction damage induced by LPS via p38 MAPK/NLRP3 signaling in IPEC-J2 cells. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2023, 178, 113870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, C.; Shen, Y.; Ma, Z.; Li, Y.; Zhang, J.; Liu, C.; Ye, Y. l-Theanine Prevents Colonic Damage via NF-κB/MAPK Signaling Pathways Induced by a High-Fat Diet in Rats. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2024, 68, 2300797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Peng, Y.; Lin, L.; Gong, Z.; Xiao, W.; Li, Y. L-Theanine Regulates the Abundance of Amino Acid Transporters in Mice Duodenum and Jejunum via the mTOR Signaling Pathway. Nutrients 2022, 15, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeed, M.; Yatao, X.; Tiantian, Z.; Qian, R.; Chao, S. 16S ribosomal RNA sequencing reveals a modulation of intestinal microbiome and immune response by dietary L-theanine supplementation in broiler chickens. Poult. Sci. 2019, 98, 842–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Lin, L.; Liu, A.; Zhang, T.; Zhang, S.; Li, Y.; Chen, J.; Gong, Z.; Liu, Z.; Xiao, W. L-Theanine affects intestinal mucosal immunity by regulating short-chain fatty acid metabolism under dietary fiber feeding. Food Funct. 2020, 11, 8369–8379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, W.; Liu, A.-X.; Liu, K.-H.; Zhang, S.; Gong, Z.-H.; Xiao, W.-J. l-Theanine Alleviates Ulcerative Colitis by Regulating Colon Immunity via the Gut Microbiota in an MHC-II-Dependent Manner. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2024, 72, 19852–19868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desai, M.J.; Gill, M.S.; Hsu, W.H.; Armstrong, D.W. Pharmacokinetics of theanine enantiomers in rats. Chirality Pharmacol. Biol. Chem. Conseq. Mol. Asymmetry 2005, 17, 154–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, Z.; Xiang, X.; Li, S.; Xie, P.; Gong, Q.; Goh, B.-C.; Wang, L. Targeting hypoxia-inducible factor-1, for cancer treatment: Recent advances in developing small-molecule inhibitors from natural compounds. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2022, 80, 379–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Zheng, S.; Guo, Z.; Wang, Y.; Yang, G.; Yin, Z.; Luo, L. L-Theanine inhibits melanoma cell growth and migration via regulating expression of the clock gene BMAL1. Eur. J. Nutr. 2022, 61, 763–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, J.; Li, P.; An, L.; Zhang, T.; Li, G. Chemoprotective effect of theanine in 1,2-dimethylhydrazine-induced colorectal cancer in rats via suppression of inflammatory parameters. J. Food Biochem. 2022, 46, e14073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shojaei-Zarghani, S.; Khosroushahi, A.Y.; Rafraf, M. Oncopreventive effects of theanine and theobromine on dimethylhydrazine-induced colon cancer model. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2021, 134, 111140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shojaei-Zarghani, S.; Rafraf, M.; Yari-Khosroushahi, A. Theanine and cancer: A systematic review of the literature. Phytother. Res. 2021, 35, 4782–4794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuu-Matsuyama, M.; Shichijo, K.; Tsuchiya, T.; Nakashima, M. The effects of cystine and theanine mixture on the chronic survival rate and tumor incidence of rats after total body X-ray irradiation. J. Radiat. Res. 2023, 64, 738–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Cao, W.; Xing, S.; Li, L.; He, Y.; Hao, Z.; Wang, S.; He, H.; Li, C.; Zhao, Q. Enhancing effects of theanine liposomes as chemotherapeutic agents for tumor therapy. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2019, 5, 3373–3379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sugiyama, T.; Sadzuka, Y. Enhancing effects of green tea components on the antitumor activity of adriamycin against M5076 ovarian sarcoma. Cancer Lett. 1998, 133, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Altınkaynak, Y.; Kural, B.; Akcan, B.A.; Bodur, A.; Özer, S.; Yuluğ, E.; Munğan, S.; Kaya, C.; Örem, A. Protective effects of L-theanine against doxorubicin-induced nephrotoxicity in rats. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2018, 108, 1524–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamaguchi, R.; Tsuchiya, T.; Miyata, G.; Sato, T.; Takahashi, K.; Miura, K.; Oshio, H.; Ohori, H.; Ariyoshi, K.; Oyamada, S. Efficacy of oral administration of cystine and theanine in colorectal cancer patients undergoing capecitabine-based adjuvant chemotherapy after surgery: A multi-institutional, randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled, phase II trial (JORTC-CAM03). Support. Care Cancer 2020, 28, 3649–3657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, H.; Ji, D.; Wu, F.; Tian, H.; Liu, K.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, B.; Zhang, G. Theanine from tea and its semi-synthetic derivative TBrC suppress human cervical cancer growth and migration by inhibiting EGFR/Met-Akt/NF-κB signaling. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2016, 791, 297–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Li, Z.; Wan, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, R.; Liu, Z.; Ji, D.; Zhang, H.; Wu, F.; Tian, H. Repression of human hepatocellular carcinoma growth by regulating Met/EGFR/VEGFR-Akt/NF-κB pathways with theanine and its derivative,(R)-2-(6, 8-Dibromo-2-oxo-2 H-chromene-3-carboxamido)-5-(ethylamino)-5-oxopentanoic ethyl ester (DTBrC). J. Agric. Food Chem. 2016, 64, 7002–7013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.; Zhou, J.; Bi, X.; Liang, J.; Lu, S.; Yan, X.; Luo, L.; Yin, Z. L-theanine suppresses the metastasis of prostate cancer by downregulating MMP9 and Snail. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2021, 89, 108556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, Y.; Ben, P.; Wang, Q.; Zhu, Y.; Yin, Z.; Luo, L. Theanine, an antitumor promoter, induces apoptosis of tumor cells via the mitochondrial pathway. Mol. Med. Rep. 2018, 18, 4535–4542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viana Veloso, G.G.; Franco, O.H.; Ruiter, R.; de Keyser, C.E.; Hofman, A.; Stricker, B.C.; Kiefte-de Jong, J.C. Baseline dietary glutamic acid intake and the risk of colorectal cancer: The Rotterdam study. Cancer 2016, 122, 899–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alagawany, M.; Abd El-Hack, M.E.; Saeed, M.; Naveed, M.; Arain, M.A.; Arif, M.; Tiwari, R.; Khandia, R.; Khurana, S.K.; Karthik, K. Nutritional applications and beneficial health applications of green tea and l-theanine in some animal species: A review. J. Anim. Physiol. Anim. Nutr. 2020, 104, 245–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Averill-Bates, D.A. The antioxidant glutathione. In Vitamins and Hormones; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2023; Volume 121, pp. 109–141. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, L.; Wen, S.; Li, Q.; Lai, X.; Chen, R.; Zhang, Z.; Li, D.; Sun, S. L-theanine relieves acute alcoholic liver injury by regulating the TNF-α/NF-κB signaling pathway in C57BL/6J mice. J. Funct. Foods 2021, 86, 104699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, K.H.; Yang, D.F.; Liu, M.Y.; Xu, W.; Li, Y.H.; Xiao, W.J. Hepatoprotective effects and mechanisms of l-theanine and epigallocatechin gallate combined intervention in alcoholic fatty liver rats. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2024, 104, 8230–8239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben, P.; Zhang, Z.; Zhu, Y.; Xiong, A.; Gao, Y.; Mu, J.; Yin, Z.; Luo, L. l-Theanine attenuates cadmium-induced neurotoxicity through the inhibition of oxidative damage and tau hyperphosphorylation. Neurotoxicology 2016, 57, 95–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Ding, J.; Xia, B.; Liu, K.; Zheng, K.; Wu, J.; Huang, C.; Yuan, X.; You, Q. L-theanine alleviates myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury by suppressing oxidative stress and apoptosis through activation of the JAK2/STAT3 pathway in mice. Mol. Med. 2024, 30, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Niño, W.R.; Correa, F.; Zúñiga-Muñoz, A.M.; José-Rodríguez, A.; Castañeda-Gómez, P.; Mejía-Díaz, E. L-theanine abates oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction in myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury by positively regulating the antioxidant response. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2024, 486, 116940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, K.; Zeng, H.; Yue, L.; Huang, J.; Ouyang, J.; Liu, Z. The Protective Effects of L-Theanine against Epigallocatechin Gallate-Induced Acute Liver Injury in Mice. Foods 2024, 13, 1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.; Yan, Q.; Tang, S.; Xiao, W.; Tan, Z. L-Theanine protects H9C2 cells from hydrogen peroxide-induced apoptosis by enhancing antioxidant capability. Med. Sci. Monit. Int. Med. J. Exp. Clin. Res. 2018, 24, 2109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.-C.; Wang, M.-H.; Soung, H.-S.; Tseng, H.-C.; Lin, F.-H.; Chang, K.-C.; Tsai, C.-C. Through its powerful antioxidative properties, l-theanine ameliorates vincristine-induced neuropathy in rats. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Chen, L.; Huang, Z.; Jia, G.; Zhao, H.; Liu, G.; Chen, X. Supplementation with L-theanine promotes intestinal antioxidant ability via Nrf2 signaling pathway in weaning piglets and H2O2-induced IPEC-J2 cells. J. Funct. Foods 2024, 121, 106433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Deng, N.; Wen, S.; Wang, X.; Huang, X.; Xia, A. The mechanism study of enhanced antioxidant capacity: Intermolecular hydrogen bonds between epigallocatechin gallate and theanine in tea. LWT 2023, 189, 115523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, X.; He, H.; Liu, C.; Wang, L.; Wang, L.; Wang, Y.; Wang, L.; Yang, C.; Wang, J.; Hou, R. L-Theanine improves emulsification stability and antioxidant capacity of diacylglycerol by hydrophobic binding β-lactoglobulin as emulsion surface stabilizer. Food Chem. 2022, 366, 130557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dasdelen, M.F.; Er, S.; Kaplan, B.; Celik, S.; Beker, M.C.; Orhan, C.; Tuzcu, M.; Sahin, N.; Mamedova, H.; Sylla, S. A novel Theanine complex, Mg-L-Theanine improves sleep quality via regulating brain electrochemical activity. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 874254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Amino Acid | Mechanism | Efficacy | Key Studies |

|---|---|---|---|

| L-Citrulline | Activates PI3K/MAPK/4E-BP1, enhances ATP redistribution, upregulates PGC-1α | Modest, less potent than BCAAs | [98,101,102] |

| Leucine | Strongly activates mTOR, promotes protein synthesis | Highly effective, gold standard | [103,104] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lv, X.; Chen, C.; Liang, Y.; Song, Y.; Liu, J.; Chen, W.; Li, H. The Emerging Role of Citrulline and Theanine in Health and Disease: A Comprehensive Review. Nutrients 2025, 17, 3496. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17213496

Lv X, Chen C, Liang Y, Song Y, Liu J, Chen W, Li H. The Emerging Role of Citrulline and Theanine in Health and Disease: A Comprehensive Review. Nutrients. 2025; 17(21):3496. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17213496

Chicago/Turabian StyleLv, Xiaokang, Chao Chen, Yan Liang, Yating Song, Jie Liu, Wenxun Chen, and Hao Li. 2025. "The Emerging Role of Citrulline and Theanine in Health and Disease: A Comprehensive Review" Nutrients 17, no. 21: 3496. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17213496

APA StyleLv, X., Chen, C., Liang, Y., Song, Y., Liu, J., Chen, W., & Li, H. (2025). The Emerging Role of Citrulline and Theanine in Health and Disease: A Comprehensive Review. Nutrients, 17(21), 3496. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17213496