Cheese Consumption and Incidence of Dementia in Community-Dwelling Older Japanese Adults: The JAGES 2019–2022 Cohort Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Setting

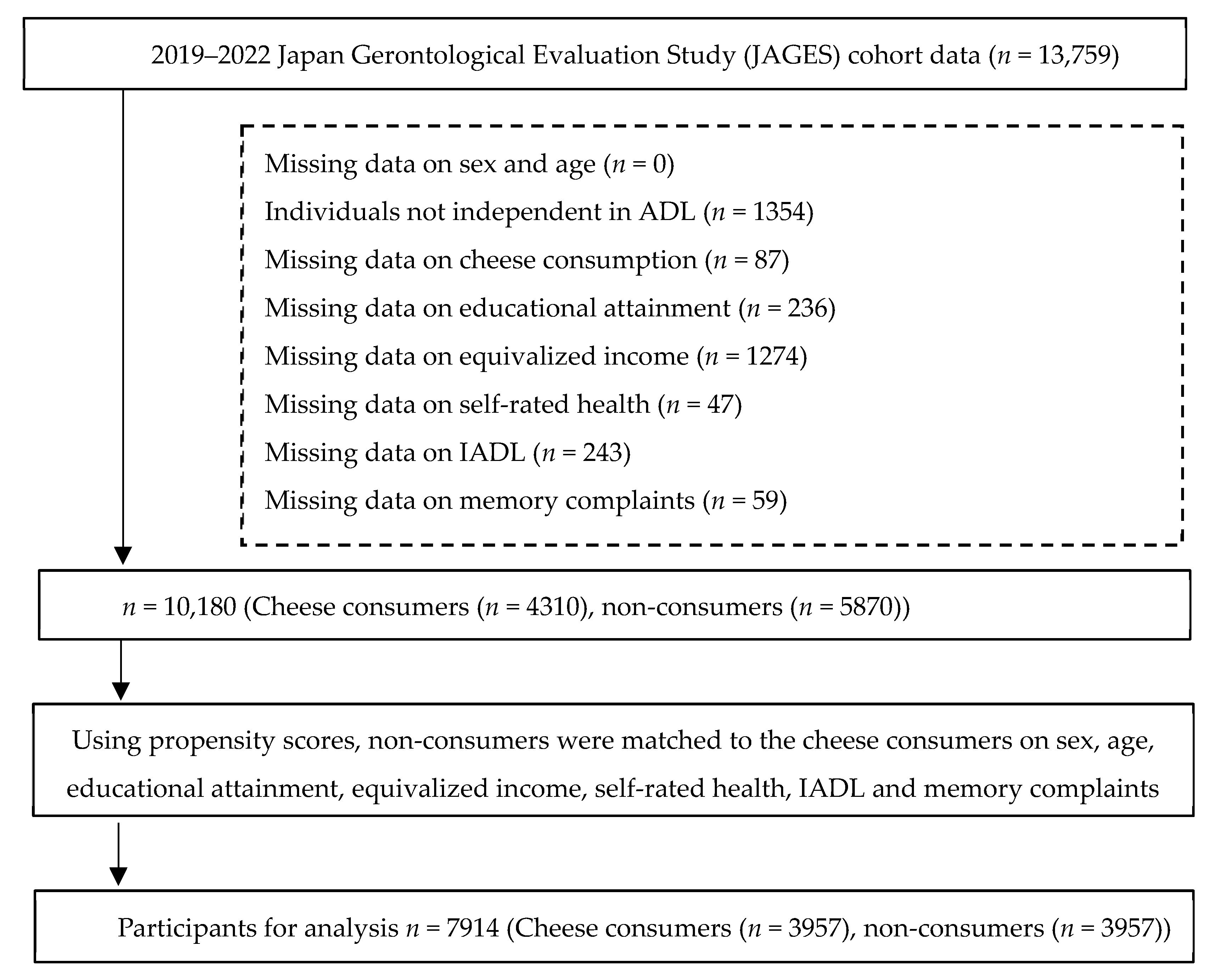

2.2. Participants

2.3. Variables

2.3.1. Outcome: Dementia Incidence

2.3.2. Exposure: Cheese Consumption

2.3.3. Covariates

2.4. Bias and Confounding Control

2.5. Study Size

2.6. Follow-Up and Censoring

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Characteristics

3.2. Patterns of Cheese Consumption

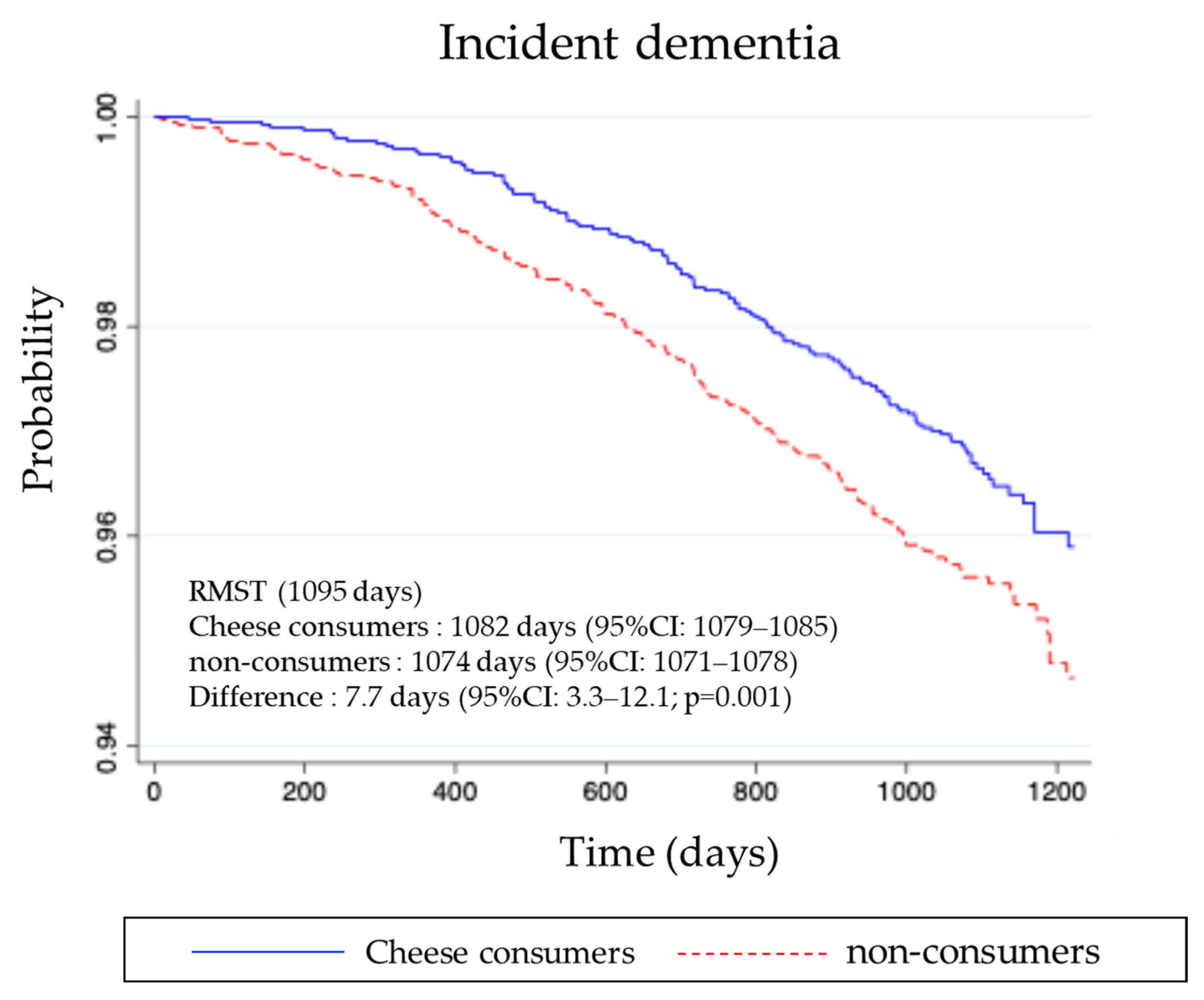

3.3. Incidence of Dementia During Follow-Up

4. Discussion

4.1. Biological Plausibility

4.2. Epidemiological Evidence Linking Cheese and Cognitive Outcomes

4.3. Regional Differences and Dose–Response Considerations

4.4. Public Health Implications

4.5. Methodological Strengths and Limitations

4.6. Future Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- WHO. Global Action Plan on the Public Health Response to Dementia 2017–2025; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Livingston, G.; Huntley, J.; Sommerlad, A.; Ames, D.; Ballard, C.; Banerjee, S.; Brayne, C.; Burns, A.; Cohen-Mansfield, J.; Cooper, C.; et al. Dementia prevention, intervention, and care: 2020 report of the Lancet Commission. Lancet 2020, 396, 413–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. Basic Plan for Promoting Dementia Measures; Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare: Tokyo, Japan, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, A.M.; Kunugi, H.; Abdelmageed, H.A.; Mandour, A.S.; Ahmed, M.E.; Ahmad, S.; Hendawy, A.O. Vitamin K in COVID-19—Potential Anti-COVID-19 Properties of Fermented Milk Fortified with Bee Honey as a Natural Source of Vitamin K and Probiotics. Fermentation 2021, 7, 202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.U.; Pirzadeh, M.; Förster, C.Y.; Shityakov, S.; Shariati, M.A. Role of Milk-Derived Antibacterial Peptides in Modern Food Biotechnology: Their Synthesis, Applications and Future Perspectives. Biomolecules 2018, 8, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bingöl, F.G.; Ağagündüz, D.; Budán, F. Probiotic Bacterium-Derived p40, p75, and HM0539 Proteins as Novel Postbiotics and Gut-Associated Immune System (GAIS) Modulation: Postbiotic-Gut-Health Axis. Microorganisms 2024, 13, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suzuki, T.; Osuka, Y.; Kojima, N.; Sasai, H.; Nakamura, K.; Oba, C.; Sasaki, M.; Kim, H. Association between the Intake/Type of Cheese and Cognitive Function in Community-Dwelling Older Women in Japan: A Cross-Sectional Cohort Study. Nutrients 2024, 16, 2800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Osuka, Y.; Kojima, N.; Sasai, H.; Nakamura, K.; Oba, C.; Sasaki, M.; Suzuki, T. Inverse Association between Cheese Consumption and Lower Cognitive Function in Japanese Community-Dwelling Older Adults Based on a Cross-Sectional Study. Nutrients 2023, 15, 3181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega, N.; Mueller, N.J.; Dehghan, A.; de Crom, T.O.E.; von Gunten, A.; Preisig, M.; Marques-Vidal, P.; Vinceti, M.; Voortman, T.; Rodondi, N.; et al. Dairy intake and cognitive function in older adults in three cohorts: A mendelian randomization study. Nutr. J. 2025, 24, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villoz, F.; Filippini, T.; Ortega, N.; Kopp-Heim, D.; Voortman, T.; Blum, M.R.; Del Giovane, C.; Vinceti, M.; Rodondi, N.; Chocano-Bedoya, P.O. Dairy Intake and Risk of Cognitive Decline and Dementia: A Systematic Review and Dose-Response Meta-Analysis of Prospective Studies. Adv. Nutr. 2024, 15, 100160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. Overview of the Long-Term Care Certification System. Available online: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/topics/kaigo/nintei/gaiyo1.html (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Austin, P.C. Optimal caliper widths for propensity-score matching when estimating differences in means and differences in proportions in observational studies. Pharm. Stat. 2011, 10, 150–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Austin, P.C. Balance diagnostics for comparing the distribution of baseline covariates between treatment groups in propensity-score matched samples. Stat Med. 2009, 28, 3083–3107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, K.M.; Fulgoni, V.L., 3rd. The association between dairy product consumption and cognitive function in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Br. J. Nutr. 2013, 109, 1135–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuesta-Triana, F.; Verdejo-Bravo, C.; Fernandez-Perez, C.; Martin-Sanchez, F.J. Effect of Milk and Other Dairy Products on the Risk of Frailty, Sarcopenia, and Cognitive Performance Decline in the Elderly: A Systematic Review. Adv. Nutr. 2019, 10, S105–S119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferland, G. Vitamin K and the nervous system: An overview of its actions. Adv. Nutr. 2012, 3, 204–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Droge, W.; Schipper, H.M. Oxidative stress and aberrant signaling in aging and cognitive decline. Aging Cell 2007, 6, 361–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marco, M.L.; Heeney, D.; Binda, S.; Cifelli, C.J.; Cotter, P.D.; Foligne, B.; Ganzle, M.; Kort, R.; Pasin, G.; Pihlanto, A.; et al. Health benefits of fermented foods: Microbiota and beyond. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2017, 44, 94–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cryan, J.F.; O’Riordan, K.J.; Cowan, C.S.M.; Sandhu, K.V.; Bastiaanssen, T.F.S.; Boehme, M.; Codagnone, M.G.; Cussotto, S.; Fulling, C.; Golubeva, A.V.; et al. The Microbiota-Gut-Brain Axis. Physiol. Rev. 2019, 99, 1877–2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovegrove, J.A.; Givens, D.I. Dairy food products: Good or bad for cardiometabolic disease? Nutr. Res. Rev. 2016, 29, 249–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Companys, J.; Pla-Paga, L.; Calderon-Perez, L.; Llaurado, E.; Sola, R.; Pedret, A.; Valls, R.M. Fermented Dairy Products, Probiotic Supplementation, and Cardiometabolic Diseases: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Adv. Nutr. 2020, 11, 834–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engberink, M.F.; Geleijnse, J.M.; de Jong, N.; Smit, H.A.; Kok, F.J.; Verschuren, W.M. Dairy intake, blood pressure, and incident hypertension in a general Dutch population. J. Nutr. 2009, 139, 582–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ylilauri, M.P.T.; Hantunen, S.; Lonnroos, E.; Salonen, J.T.; Tuomainen, T.P.; Virtanen, J.K. Associations of dairy, meat, and fish intakes with risk of incident dementia and with cognitive performance: The Kuopio Ischaemic Heart Disease Risk Factor Study (KIHD). Eur. J. Nutr. 2022, 61, 2531–2542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozawa, M.; Ohara, T.; Ninomiya, T.; Hata, J.; Yoshida, D.; Mukai, N.; Nagata, M.; Uchida, K.; Shirota, T.; Kitazono, T.; et al. Milk and dairy consumption and risk of dementia in an elderly Japanese population: The Hisayama Study. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2014, 62, 1224–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Fu, Z.; Chung, M.; Jang, D.J.; Lee, H.J. Role of milk and dairy intake in cognitive function in older adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutr. J. 2018, 17, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Willette, A.A.; Wang, Q.; Pollpeter, A.; Larsen, B.A.; Mohammadiarvejeh, P.; Fili, M. Alzheimer’s Disease Genetic Influences Impact the Associations between Diet and Resting-State Functional Connectivity: A Study from the UK Biobank. Nutrients 2023, 15, 3390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agriculture and Horticulture Development Board. Europe: How Much Do They Consume? 2025. Available online: https://ahdb.org.uk/europe-how-much-do-they-consume (accessed on 30 September 2025).

| Variables | Before PSM Cheese Consumers, n = 5870 Non-Consumers, n = 4310 | After PSM Cheese Consumers, n = 3957 Non-Consumers, n = 3957 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cheese Consumers; n, (%) | Non-Consumers n, (%) | Cheese Consumers, n, (%) | Non-Consumers n, (%) | ||

| Sex | Male | 2642 (45.0) | 2543 (59.0) | 2379 (60.1) | 2225 (56.2) |

| Female | 3228 (55.0) | 1767 (41.0) | 1578 (39.9) | 1732 (43.8) | |

| Age, years | 65–69 | 1470 (25.0) | 1122 (26.0) | 847 (21.4) | 1045 (26.4) |

| 70–74 | 1864 (31.8) | 1328 (31.0) | 1188 (30.0) | 1222 (30.9) | |

| 75–79 | 1492 (25.4) | 988 (22.9) | 1090 (27.5) | 928 (23.5) | |

| 80–84 | 756 (12.9) | 585 (13.6) | 603 (15.2) | 513 (13.0) | |

| ≥85 | 288 (4.9) | 287 (6.7) | 229 (5.8) | 249 (6.3) | |

| Equivalized income, million yen | <2.00 | 2557 (43.7) | 2217 (51.4) | 1993 (50.4) | 1976 (49.9) |

| 2.00–3.99 | 2496 (42.5) | 1582 (36.7) | 1472 (37.2) | 1494 (37.8) | |

| ≥4.00 | 817 (13.9) | 511 (11.9) | 492 (12.4) | 487 (12.3) | |

| Educational attainment, years | <6 | 12 (0.2) | 22 (0.5) | 12 (0.3) | 13 (0.3) |

| 6–9 | 1124 (19.2) | 1251 (29.0) | 1124 (28.4) | 1034 (26.1) | |

| ≥10 | 4734 (80.7) | 3037 (70.5) | 2821 (71.3) | 2910 (73.5) | |

| Self-rated health | Excellent or Good | 5348 (91.0) | 3774 (87.6) | 3480 (87.9) | 3545 (89.6) |

| Fair or Poor | 522 (8.9) | 536 (12.4) | 477 (12.1) | 412 (10.4) | |

| Instrumental activities of daily living (IADL) | Independent | 5548 (94.5) | 3847 (89.2) | 3635 (91.9) | 3626 (91.6) |

| Dependent | 322 (5.5) | 463 (10.7) | 322 (8.1) | 331 (8.4) | |

| Memory complaints | No | 5216 (88.9) | 3679 (85.4) | 3373 (85.2) | 3426 (86.6) |

| Yes | 654 (11.1) | 631 (14.7) | 584 (14.8) | 531 (13.4) | |

| Variables | Cheese Consumers (n = 3957) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | ||

| Frequency of Cheese consumption | >5 times/week | 527 | 13.3 |

| 3–4 times/week | 578 | 14.6 | |

| 1–2 times/week | 2852 | 72.1 | |

| Types of cheese consumption, ≥1 time/week | processed cheese | 3081 | 82.7 |

| fresh cheese | 144 | 3.9 | |

| white mold cheese | 289 | 7.8 | |

| blue mold cheese | 18 | 0.5 | |

| other | 195 | 5.2 | |

| Model 1 | Model 2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95%CI) | p | HR (95%CI) | p | |

| non-consumers (Ref.) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Cheese consumers (n = 3957) | 0.76 (0.60–0.95) | 0.02 | 0.79 (0.63–0.99) | 0.04 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jeong, S.; Suzuki, T.; Inoue, Y.; Bang, E.; Nakamura, K.; Sasaki, M.; Kondo, K. Cheese Consumption and Incidence of Dementia in Community-Dwelling Older Japanese Adults: The JAGES 2019–2022 Cohort Study. Nutrients 2025, 17, 3363. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17213363

Jeong S, Suzuki T, Inoue Y, Bang E, Nakamura K, Sasaki M, Kondo K. Cheese Consumption and Incidence of Dementia in Community-Dwelling Older Japanese Adults: The JAGES 2019–2022 Cohort Study. Nutrients. 2025; 17(21):3363. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17213363

Chicago/Turabian StyleJeong, Seungwon, Takao Suzuki, Yusuke Inoue, Eunji Bang, Kentaro Nakamura, Mayuki Sasaki, and Katsunori Kondo. 2025. "Cheese Consumption and Incidence of Dementia in Community-Dwelling Older Japanese Adults: The JAGES 2019–2022 Cohort Study" Nutrients 17, no. 21: 3363. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17213363

APA StyleJeong, S., Suzuki, T., Inoue, Y., Bang, E., Nakamura, K., Sasaki, M., & Kondo, K. (2025). Cheese Consumption and Incidence of Dementia in Community-Dwelling Older Japanese Adults: The JAGES 2019–2022 Cohort Study. Nutrients, 17(21), 3363. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17213363