From Healthy Eating to Positive Mental Health in Adolescents: A Moderated Mediation Model Involving Stress Management and Peer Support

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Setting

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Sample Characteristics

3.2. Descriptive Statistics and Correlations

3.3. Preliminary Analyses: Covariates

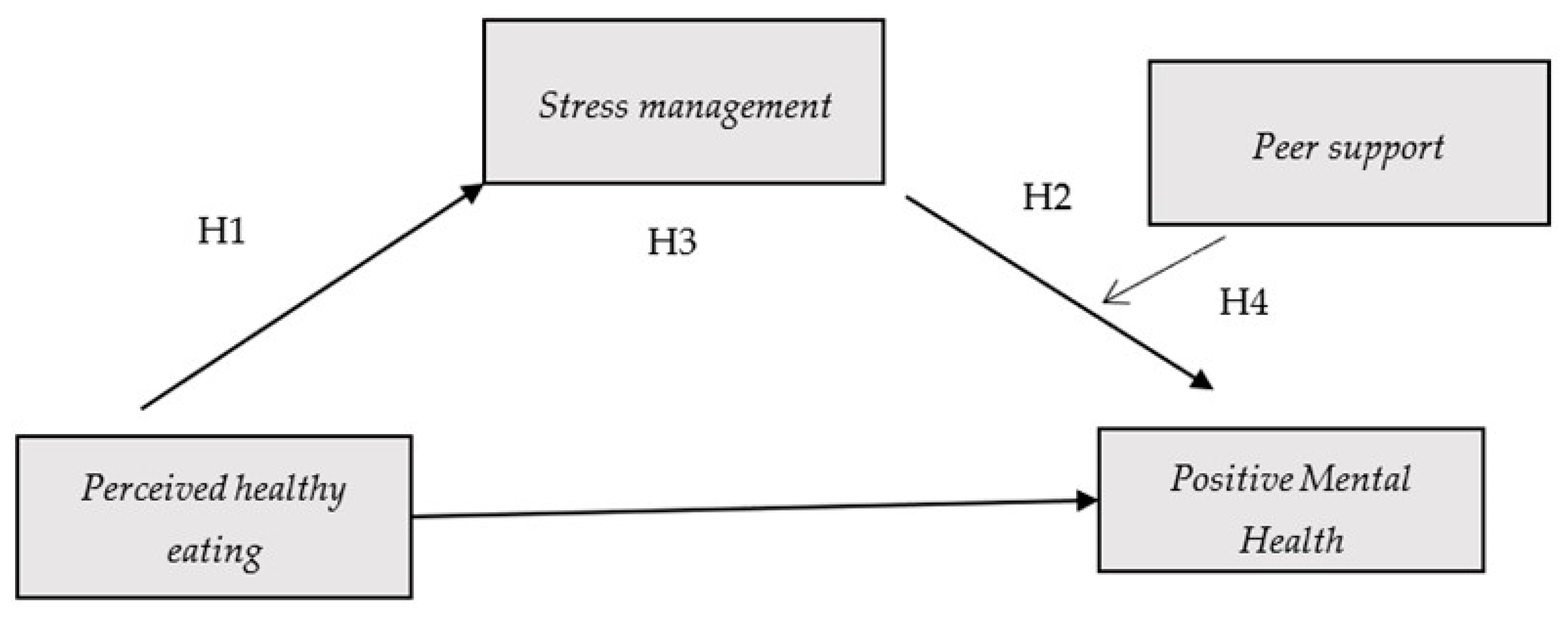

3.4. Inferential Analyses: Theoretical Models

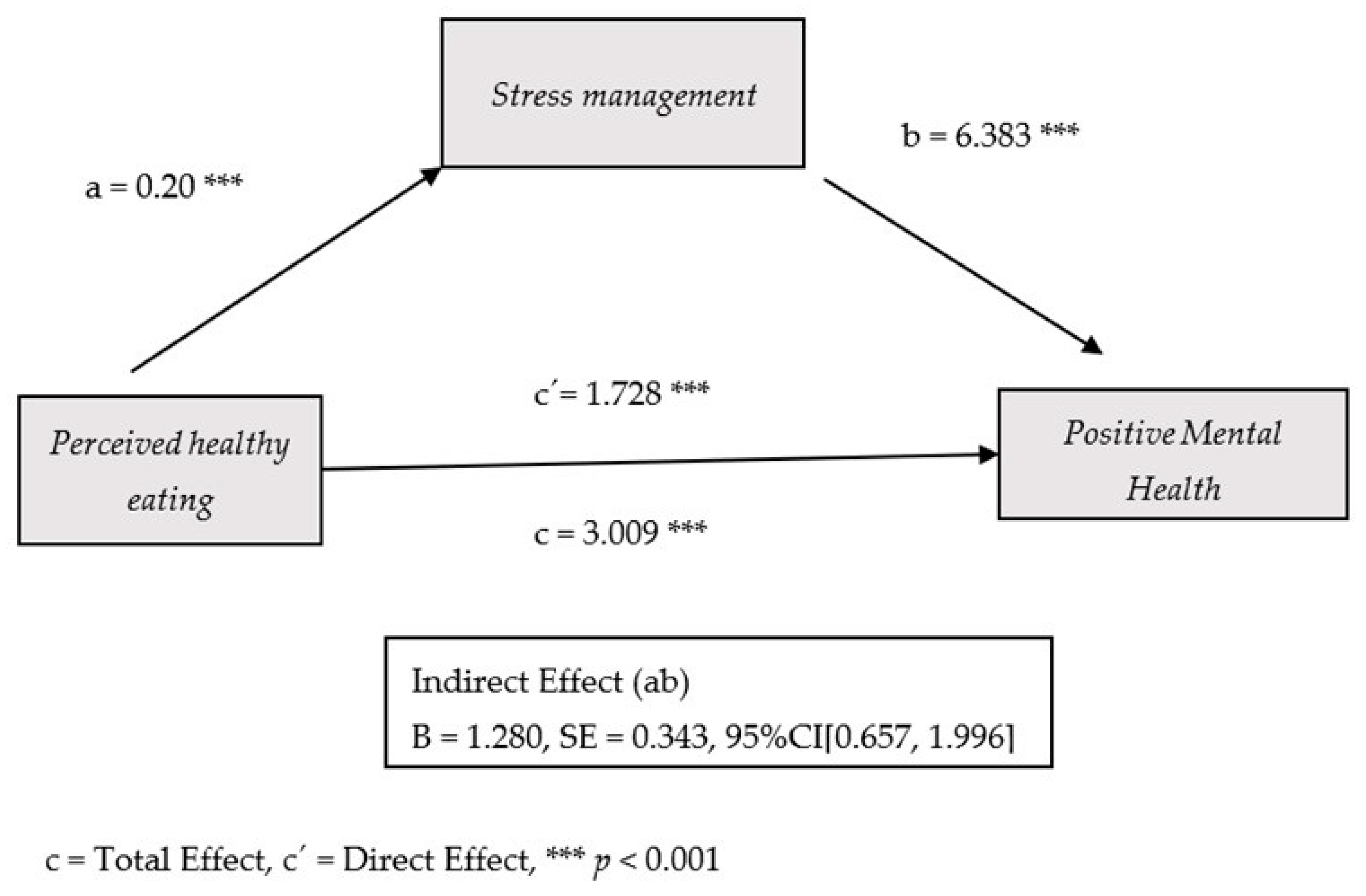

3.4.1. Simple Mediation Model (Perceived Healthy Eating, Stress Management and PMH)

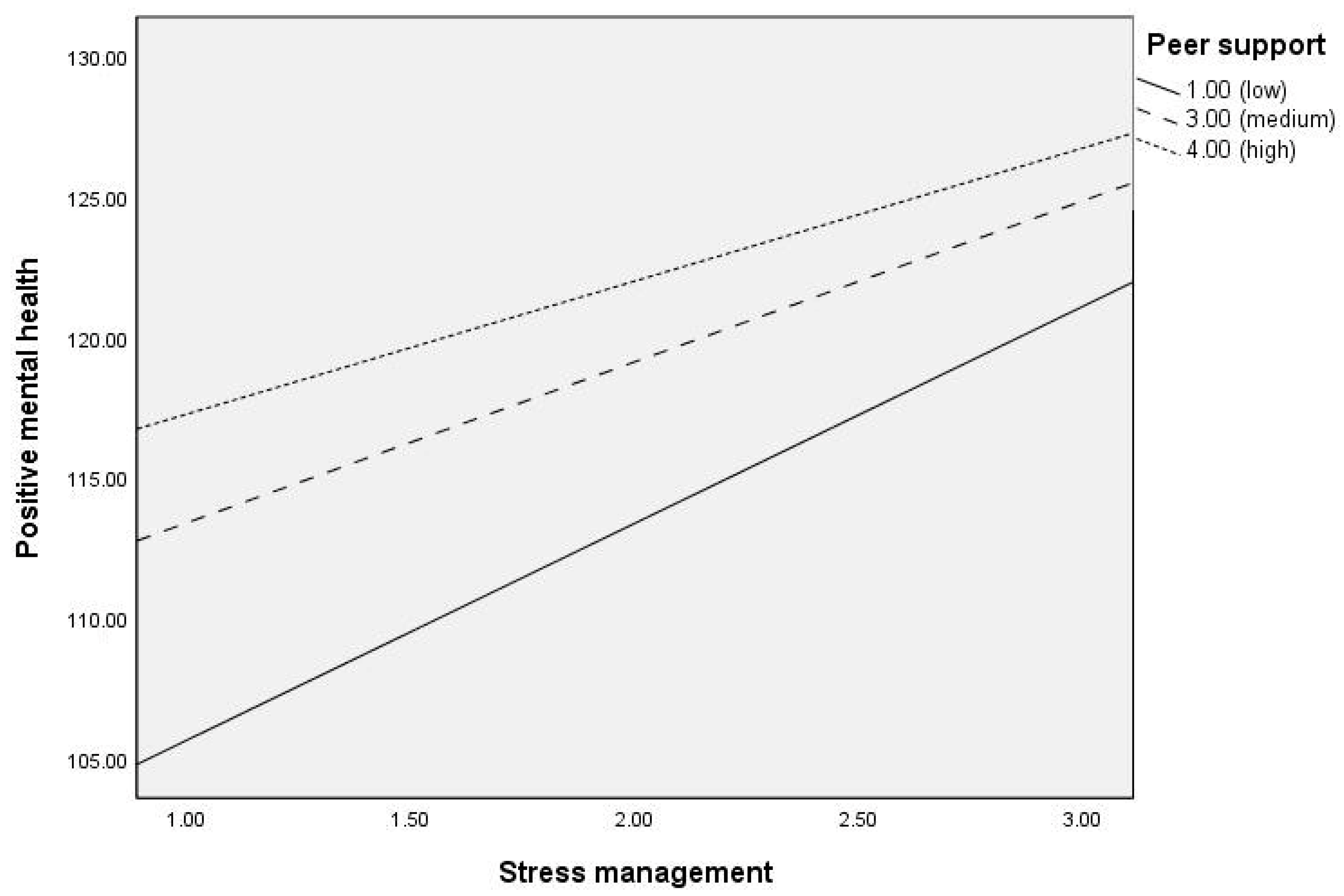

3.4.2. Moderated Mediation Model (Peer Support as a Moderating Variable)

4. Discussion

Limitations and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PMH | Positive Mental Health |

References

- Blakemore, S.-J. Adolescence and mental health. Lancet 2019, 393, 2030–2031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. Mental Health of Adolescents. World Health Organization. Available online: https://www.who.int/es/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/adolescent-mental-health (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Ramos, P.; Luna, S.; Rivera, F.; Moreno, C.; Moreno-Maldonado, C.; Leal-López, E.; Majón-Valpuesta, D.; Villafuerte-Díaz, A.; Ciria-Barreiro, E.; Velo-Ramírez, S.; et al. La Salud Mental es Cosa de Niños, Niñas y Adolescentes. Barómetro de Opinión de la Infancia y la Adolescencia 2023–2024; UNICEF España: Madrid, Spain, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Hosker, D.K.; Elkins, R.M.; Potter, M.P. Promoting Mental Health and Wellness in Youth Through Physical Activity, Nutrition, and Sleep. Child Adolesc. Psychiatr. Clin. N. Am. 2019, 28, 171–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mawer, T.; Kent, K.; Williams, A.D.; McGowan, C.J.; Murray, S.; Bird, M.L.; Hardcastle, S.; Bridgman, H. The Knowledge, Barriers and Opportunities to Improve Nutrition and Physical Activity amongst Young People Attending an Australian Youth Mental Health Service: A Mixed-Methods Study. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2022, 22, 789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, R.S.; Chan, B.N.K.; Lai, S.I.; Tung, K.T.S. School-Based Eating Disorder Prevention Programmes and Their Impact on Adolescent Mental Health: Systematic Review. BJPsych Open 2024, 10, e196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Głąbska, D.; Guzek, D.; Groele, B.; Gutkowska, K. Fruit and Vegetables Intake in Adolescents and Mental Health: A Systematic Review. Rocz. Panstw. Zakl. Hig. 2020, 71, 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talib, M.; Rachdi, M.; Papazova, A.; Nicolis, H. The Role of Dietary Patterns and Nutritional Supplements in the Management of Mental Disorders in Children and Adolescents: An Umbrella Review of Meta-Analyses. Can. J. Psychiatry 2024, 69, 567–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chopra, C.; Mandalika, S.; Kinger, N. Does Diet Play a Role in the Prevention and Management of Depression among Adolescents? A Narrative Review. Nutr. Health 2021, 27, 243–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanna, P.; Chattu, V.K.; Aeri, B.T. Nutritional Aspects of Depression in Adolescents—A Systematic Review. Int. J. Prev. Med. 2019, 10, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogden, C.L.; Ansai, N.; Fryar, C.D.; Wambogo, E.A.; Brody, D.J. Depression and Diet Quality, US Adolescents and Young Adults: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2015–March 2020. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2025, 125, 247–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalid, S.; Williams, C.M.; Reynolds, S.A. Is There an Association between Diet and Depression in Children and Adolescents? A Systematic Review. Br. J. Nutr. 2016, 116, 2097–2108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Utter, J.; Denny, S.; Lucassen, M.; Dyson, B. Adolescent Cooking Abilities and Behaviors: Associations with Nutrition and Emotional Well-Being. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2016, 48, 35–41.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bremner, J.D.; Moazzami, K.; Wittbrodt, M.T.; Nye, J.A.; Lima, B.B.; Gillespie, C.F.; Rapaport, M.H.; Pearce, B.D.; Shah, A.J.; Vaccarino, V. Diet, Stress and Mental Health. Nutrients 2020, 12, 2428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D.; Xiao, W.; Tan, B.; Zeng, Y.; Li, S.; Zhou, J.; Shan, S.; Wu, J.; Yi, Q.; Zhang, R.; et al. Association between Dietary Habits and Emotional and Behavioral Problems in Children: The Mediating Role of Self-Concept. Front. Nutr. 2025, 12, 1426485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancone, S.; Corrado, S.; Tosti, B.; Spica, G.; Di Siena, F.; Misiti, F.; Diotaiuti, P. Enhancing Nutritional Knowledge and Self-Regulation Among Adolescents: Efficacy of a Multifaceted Food Literacy Intervention. Front. Psychol. 2024, 15, 1405414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Branje, S. Adolescent Identity Development in Context. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2022, 45, 101286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ragelienė, T. Links of Adolescents’ Identity Development and Relationship with Peers: A Systematic Literature Review. J. Can. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2016, 25, 97–105. [Google Scholar]

- Telzer, E.H.; van Hoorn, J.; Rogers, C.R.; Do, K.T. Social Influence on Positive Youth Development: A Developmental Neuroscience Perspective. Adv. Child Dev. Behav. 2018, 54, 215–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Letkiewicz, A.M.; Li, L.Y.; Hoffman, L.M.K.; Shankman, S.A. A Prospective Study of the Relative Contribution of Adolescent Peer Support Quantity and Quality to Depressive Symptoms. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2023, 64, 1314–1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roach, A. Supportive Peer Relationships and Mental Health in Adolescence: An Integrative Review. Issues Ment. Health Nurs. 2018, 39, 723–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surzykiewicz, J.; Skalski, S.B.; Sołbut, A.; Rutkowski, S.; Konaszewski, K. Resilience and Regulation of Emotions in Adolescents: Serial Mediation Analysis through Self-Esteem and the Perceived Social Support. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 8007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, X.-Q.; Wang, L.-H.; Zhang, G.-D.; Liang, X.-B.; Li, J.; Zimmerman, M.A.; Wang, J.-L. The Promotive Effects of Peer Support and Active Coping on the Relationship between Bullying Victimization and Depression among Chinese Boarding Students. Psychiatry Res. 2017, 256, 59–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haidar, A.; Ranjit, N.; Saxton, D.; Hoelscher, D.M. Perceived Parental and Peer Social Support Is Associated with Healthier Diets in Adolescents. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2019, 51, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bauer, G.F.; Roy, M.; Bakibinga, P.; Contu, P.; Downe, S.; Eriksson, M.; Espnes, G.A.; Jensen, B.B.; Juvinya Canal, D.; Lindström, B.; et al. Future Directions for the Concept of Salutogenesis: A Position Article. Health Promot. Int. 2020, 35, 187–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hewis, J. A Salutogenic Approach: Changing the Paradigm. J. Med. Imaging Radiat. Sci. 2023, 54 (Suppl. 2), S17–S21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittelmark, M.B.; Bauer, G.F. Salutogenesis as a Theory, as an Orientation and as the Sense of Coherence. In The Handbook of Salutogenesis, 2nd ed.; Mittelmark, M.B., Bauer, G.F., Vaandrager, L., Pelikan, J.M., Sagy, S., Eriksson, M., Lindström, B., Meier Magistretti, C., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; Available online: https://link.springer.com/book/10.1007/978-3-030-79515-3 (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Antonovsky, A. The salutogenic model as a theory to guide health promotion. Health Promot. Int. 1996, 11, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Moya, I.; Morgan, A. The Utility of Salutogenesis for Guiding Health Promotion: The Case for Young People’s Well-Being. Health Promot. Int. 2017, 32, 723–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renwick, L.; Pedley, R.; Johnson, I.; Bell, V.; Lovell, K.; Bee, P.; Brooks, H. Conceptualisations of Positive Mental Health and Wellbeing among Children and Adolescents in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: A Systematic Review and Narrative Synthesis. Health Expect. 2022, 25, 61–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, A.; Ziglio, E. Revitalising the Evidence Base for Public Health: An Assets Model. Promot. Educ. 2007, 14 (Suppl. 2), 17–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keyes, C.L.M. Promoting and Protecting Mental Health as Flourishing: A Complementary Strategy for Improving National Mental Health. Am. Psychol. 2007, 62, 95–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lluch-Canut, M.T. Construcción de una Escala para Evaluar la Salud Mental Positiva. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain, 1999. Available online: https://www.tdx.cat/handle/10803/2366 (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Sequeira, C.; Carvalho, J.; Sampaio, F.; Sá, L.; Lluch-Canut, T.; Roldán-Merino, J. Avaliação das Propriedades Psicométricas do Questionário de Saúde Mental Positiva em Estudantes Portugueses do Ensino Superior. Rev. Port. Enferm. Saúde Ment. 2014, 11, 45–53. [Google Scholar]

- Carbacas-Soleno, J.; Mendoza-Bolaño, L.M.; Fortich-Pérez, D.J. Validación del Cuestionario de Salud Mental Positiva de Lluch en Jóvenes Estudiantes en el Municipio de Carmen de Bolívar; Universidad Tecnológica de Bolívar: Cartagena, Colombia, 2016; Available online: https://repositorio.utb.edu.co/entities/publication/1a73a1d0-ecd2-4561-8427-114778bbad2d (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Atroszko, P.A.; Sawicki, A.; Sendal, L.; Atroszko, B. CER Comparative European Research 2017. In Proceedings of the Proceedings|Research Track of the 7th Biannual CER Comparative European Research Conference, London, UK, 29–31 March 2017; Sciemcee: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Gago, C.M.; Lopez-Cepero, A.; O’Neill, J.; Tamez, M.; Tucker, K.; Orengo, J.F.R.; Mattei, J. Association of a Single-Item Self-Rated Diet Construct with Diet Quality Measured with the Alternate Healthy Eating Index. Front. Nutr. 2021, 8, 646694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoeppner, B.B.; Kelly, J.F.; Urbanoski, K.A.; Slaymaker, V. Comparative Utility of a Single-Item versus Multiple-Item Measure of Self-Efficacy in Predicting Relapse among Young Adults. J. Subst. Abus. Treat. 2011, 41, 305–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.H.; Joung, H.; Choi, S.K. Exploring the Potential Utility of a Single-Item Perceived Diet Quality Measure. Nutr. Res. Pract. 2024, 18, 845–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loftfield, E.; Yi, S.; Immerwahr, S.; Eisenhower, D. Construct Validity of a Single-Item, Self-Rated Question of Diet Quality. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2015, 47, 181–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukoševičiūtė, J.; Gariepy, G.; Mabelis, J.; Gaspar, T.; Joffė-Luinienė, R.; Šmigelskas, K. Single-Item Happiness Measure Features Adequate Validity among Adolescents. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 884520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eddy, C.L.; Herman, K.C.; Reinke, W.M. Single-Item Teacher Stress and Coping Measures: Concurrent and Predictive Validity and Sensitivity to Change. J. Sch. Psychol. 2019, 76, 17–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elo, A.L.; Leppänen, A.; Jahkola, A. Validity of a Single-Item Measure of Stress Symptoms. Scand. J. Work Environ. Health 2003, 29, 444–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, M.S.; Iliescu, D.; Greiff, S. Single Item Measures in Psychological Science: A Call to Action. Eur. J. Psychol. Assess. 2022, 38, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, H. The Single-Item Questionnaire. Health Prof. Educ. 2018, 4, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barco Leme, A.C.; Fisberg, R.M.; Baranowski, T.; Nicklas, T.; Callender, C.S.; Kasam, A.; Tucunduva Philippi, S.; Thompson, D. Perceptions about Health, Nutrition Knowledge, and MyPlate Food Categorization among US Adolescents: A Qualitative Study. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2021, 53, 110–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giménez-Legarre, N.; Santaliestra-Pasías, A.M.; Beghin, L.; Dallongeville, J.; de la O, A.; Gilbert, C.; González-Gross, M.; De Henauw, S.; Kafatos, A.; Kersting, M.; et al. Dietary Patterns and Their Relationship with the Perceptions of Healthy Eating in European Adolescents: The HELENA Study. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 2019, 38, 703–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medeiros, G.C.B.S.d.; Azevedo, K.P.M.d.; Garcia, D.; Oliveira Segundo, V.H.; Mata, Á.N.d.S.; Fernandes, A.K.P.; Santos, R.P.D.; Trindade, D.D.B.d.B.; Moreno, I.M.; Guillén Martínez, D.; et al. Effect of School-Based Food and Nutrition Education Interventions on the Food Consumption of Adolescents: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 10522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samad, N.; Bearne, L.; Noor, F.M.; Akter, F.; Parmar, D. School-Based Healthy Eating Interventions for Adolescents Aged 10-19 Years: An Umbrella Review. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2024, 21, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cena, H.; Calder, P.C. Defining a Healthy Diet: Evidence for the Role of Contemporary Dietary Patterns in Health and Disease. Nutrients 2020, 12, 334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Healthy Diet. Who.Int. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/healthy-diet (accessed on 3 October 2025).

- IBM Corp. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows; Version 27.0; IBM: Armonk, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Bono, R.; Blanca, M.J.; Arnau, J.; Gómez-Benito, J. Non-Normal Distributions Commonly Used in Health, Education, and Social Sciences: A Systematic Review. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 1602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Field, A. Discovering Statistics Using IBM SPSS Statistics, 4th ed.; SAGE Publications: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Tabachnick, B.G.; Fidell, L.S. Using Multivariate Statistics, 7th ed.; Pearson: Boston, MA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Westland, J.C. Lower Bounds on Sample Size in Structural Equation Modeling. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2010, 9, 476–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2022; Available online: http://www.guilford.com/books/Introduction-to-Mediation-Moderation-and-Conditional-Process-Analysis/Andrew-Hayes/9781462549030 (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Viner, R.M.; Ozer, E.M.; Denny, S.; Marmot, M.; Resnick, M.; Fatusi, A.; Currie, C. Adolescence and the Social Determinants of Health. Lancet 2012, 379, 1641–1652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, A.; Stevens, M.; Purtscheller, D.; Knapp, M.; Fonagy, P.; Evans-Lacko, S.; Paul, J. Mobilising Social Support to Improve Mental Health for Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review Using Principles of Realist Synthesis. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0251750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mateo-Orcajada, A.; Abenza-Cano, L.; Molina-Morote, J.M.; Vaquero-Cristóbal, R. The Influence of Physical Activity, Adherence to Mediterranean Diet, and Weight Status on the Psychological Well-Being of Adolescents. BMC Psychol. 2024, 12, 410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yim, H.-R.; Yun, H.J.; Lee, J.H. An Investigation on Korean Adolescents’ Dietary Consumption: Focused on Sociodemographic Characteristics, Physical Health, and Mental Health. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 9773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramón-Arbués, E.; Martínez Abadía, B.; Granada López, J.M.; Echániz Serrano, E.; Pellicer García, B.; Juárez Vela, R.; Guerrero Portillo, S.; Sáez Guinoa, M. Eating Behavior and Its Relationship with Stress, Anxiety, Depression, and Insomnia in University Students. Nutr. Hosp. 2019, 36, 1339–1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Errisuriz, V.L.; Pasch, K.E.; Perry, C.L. Perceived Stress and Dietary Choices: The Moderating Role of Stress Management. Eat. Behav. 2016, 22, 211–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casey, B.J.; Heller, A.S.; Gee, D.G.; Cohen, A.O. Development of the Emotional Brain. Neurosci. Lett. 2019, 693, 29–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somerville, L.H.; Jones, R.M.; Casey, B.J. A Time of Change: Behavioral and Neural Correlates of Adolescent Sensitivity to Appetitive and Aversive Environmental Cues. Brain Cogn. 2010, 72, 124–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steinberg, L. Age of Opportunity: Lessons from the New Science of Adolescence; Harper Paperbacks: New York, NY, USA, 2014; p. 264. [Google Scholar]

- Bromley, K.; Sacks, D.D.; Boyes, A.; Driver, C.; Hermens, D.F. Health Enhancing Behaviors in Early Adolescence: An Investigation of Nutrition, Sleep, Physical Activity, Mindfulness and Social Connectedness and Their Association with Psychological Distress and Wellbeing. Front. Psychiatry 2024, 15, 1413268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chung, S.J.; Ersig, A.L.; McCarthy, A.M. The Influence of Peers on Diet and Exercise among Adolescents: A Systematic Review. J. Pediatr. Nurs. 2017, 36, 44–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheuplein, M.; van Harmelen, A.L. The Importance of Friendships in Reducing Brain Responses to Stress in Adolescents Exposed to Childhood Adversity: A Preregistered Systematic Review. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2022, 45, 101310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzpatrick, M.M.; Anderson, A.M.; Browning, C.; Ford, J.L. Relationship between Family and Friend Support and Psychological Distress in Adolescents. J. Pediatr. Health Care 2024, 38, 804–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Xu, J.; Fu, S.; Tsang, U.K.; Ren, H.; Zhang, S.; Hu, Y.; Zeman, J.L.; Han, Z.R. Friend Emotional Support and Dynamics of Adolescent Socioemotional Problems. J. Youth Adolesc. 2024, 53, 2732–2745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, B.B.; Larson, J. Peer Relationships in Adolescence. In Handbook of Adolescent Psychology; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Hobfoll, S.E. Conservation of Resources: A New Attempt at Conceptualizing Stress. Am. Psychol. 1989, 44, 513–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Compas, B.E.; Jaser, S.S.; Bettis, A.H.; Watson, K.H.; Gruhn, M.A.; Dunbar, J.P.; Williams, E.; Thigpen, J.C. Coping, Emotion Regulation, and Psychopathology in Childhood and Adolescence: A Meta-Analysis and Narrative Review. Psychol. Bull. 2017, 143, 939–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmer-Gembeck, M.J.; Skinner, E.A. Review: The Development of Coping across Childhood and Adolescence: An Integrative Review and Critique of Research. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 2011, 35, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Self Efficacy: The Exercise of Control; W.H. Freeman: New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Prinstein, M.J.; Dodge, K.A. (Eds.) Understanding Peer Influence in Children and Adolescents; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2008; Available online: http://www.guilford.com (accessed on 3 October 2025).

- Seligman, M.E.P. Flourish: A Visionary New Understanding of Happiness and Well-Being; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Seligman, M. PERMA and the Building Blocks of Well-Being. J. Posit. Psychol. 2018, 13, 333–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kern, M.L.; Benson, L.; Steinberg, E.A.; Steinberg, L. The EPOCH Measure of Adolescent Well-Being. Psychol. Assess. 2016, 28, 586–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ardic, A.; Erdogan, S. The Effectiveness of the COPE Healthy Lifestyles TEEN Program: A School-Based Intervention in Middle School Adolescents with 12-Month Follow-Up. J. Adv. Nurs. 2017, 73, 1377–1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Subramanyam, A.A.; Somaiya, M.; De Sousa, A. Mental Health and Well-Being in Children and Adolescents. Indian J. Psychiatry 2024, 66 (Suppl. 2), S304–S319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Govindan, R.; Rajeswari, B.; Kommu, J.V.S. Nurture Clinic: Promoting Mental Health of Children and Adolescents. J. Fam. Med. Prim. Care 2024, 13, 2375–2378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qutteina, Y.; Hallez, L.; Raedschelders, M.; De Backer, C.; Smits, T. Food for Teens: How Social Media Is Associated with Adolescent Eating Outcomes. Public Health Nutr. 2022, 25, 290–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sina, E.; Boakye, D.; Christianson, L.; Ahrens, W.; Hebestreit, A. Social Media and Children’s and Adolescents’ Diets: A Systematic Review of the Underlying Social and Physiological Mechanisms. Adv. Nutr. 2022, 13, 913–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | n | % | Mean | SD | Max | Min |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 13.62 | 0.70 | 13 | 15 | ||

| 13 years old | 257 | 50.9 | ||||

| 14 years old | 184 | 36.4 | ||||

| 15 years old | 64 | 12.7 | ||||

| Nationality (Spanish) | 446 | 88.1 | ||||

| Gender | ||||||

| Women | 260 | 51.5 | ||||

| Men | 245 | 48.5 | ||||

| Family situation | ||||||

| Parents living together | 352 | 69.7 | ||||

| Divorced/separated parents | 115 | 22.8 | ||||

| Other family models | 38 | 7.5 | ||||

| Grade repetition (yes) | 149 | 29.5 | ||||

| Educational support (yes) | 221 | 43.8 |

| Mean | SD | Range | Asym | Kurt | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Perceived healthy eating | 1.99 | 0.99 | 0–4 | −0.03 | −0.52 | 0.21 ** | 0.18 ** | 0.27 ** |

| 2. Stress management | 2.10 | 1.05 | 0–4 | −0.112 | −0.521 | 0.09 * | 0.41 ** | |

| 3. Peer support | 2.62 | 1.15 | 0–4 | −0.68 | −0.27 | 0.27 ** | ||

| 4. Positive Mental Health | 118.33 | 15.01 | 65–155 | −0.41 | 0.027 |

| Perceived Healthy Eating | Stress Management | Peer Support | Positive Mental Health | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | Yes (p < 0.001) | |||

| Gender | Yes (p < 0.001) | Yes (p < 0.001) | ||

| Nationality | Yes (p = 0.043) | Yes (p < 0.001) | Yes (p < 0.001) | |

| School retention | Yes (p = 0.042) | Yes (p = 0.021) | ||

| Receives educational support | Yes (p = 0.020) | Yes (p < 0.001) |

| DV: Stress Management | R2 | F | p | Beta | SE | t | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model summary | 0.14 | 12.12 | <0.001 | ||||

| IV: Perceived healthy eating | 0.200 | 0.046 | 4.286 | <0.001 | |||

| Age (covariate) | −0.039 | 0.092 | −0.424 | 0.671 | |||

| Gender (covariate) | −0.622 | 0.091 | −6.790 | <0.001 | |||

| Nationality (covariate) | 0.122 | 0.146 | 0.834 | 0.404 | |||

| Educational support (covariate) | −0.033 | 0.093 | −0.353 | 0.723 | |||

| Grade repetition (covariate) | 0.118 | 0.144 | 0.821 | 0.411 | |||

| DV: Positive mental health | |||||||

| Model summary | 0.32 | 30.58 | <0.001 | ||||

| IV: Perceived healthy eating | 1.728 | 0.599 | 2.884 | 0.004 | |||

| M: Stress management | 6.383 | 0.582 | 10.958 | <0.001 | |||

| Age (covariate) | 0.823 | 1.167 | 0.705 | 0.480 | |||

| Gender (covariate) | −2.343 | 1.206 | −1.942 | 0.052 | |||

| Nationality (covariate) | −5.376 | 1.843 | −2.916 | 0.003 | |||

| Educational support (covariate) | −2.440 | 1.178 | −2.071 | 0.038 | |||

| Grade repetition (covariate) | 2.525 | 1.815 | 1.391 | 0.164 |

| DV: Stress Management | R2 | F | p | Beta | SE | t | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model summary | 0.14 | 12.126 | <0.001 | ||||

| IV: Perceived healthy eating | 0.200 | 0.046 | 4.286 | <0.001 | |||

| Age (covariate) | −0.039 | 0.092 | −0.424 | 0.671 | |||

| Gender (covariate) | −0.622 | 0.091 | −6.791 | <0.001 | |||

| Nationality (covariate) | 0.122 | 0.146 | 0.834 | 0.404 | |||

| Educational support (covariate) | −0.033 | 0.093 | −0.353 | 0.723 | |||

| Grade repetition (covariate) | 0.118 | 0.144 | 0.821 | 0.411 | |||

| DV: Positive mental health | |||||||

| Model summary | 0.36 | 29.285 | <0.001 | ||||

| IV: Perceived healthy eating | 1.288 | 0.584 | 2.205 | 0.027 | |||

| M: Stress management | 8.719 | 1.341 | 6.497 | <0.001 | |||

| Mo: Peer Support | 4.863 | 1.107 | 4.391 | <0.001 | |||

| Interaction M * Mo | −0.995 | 0.464 | −2.114 | 0.032 | |||

| Age (covariate) | 1.443 | 1.133 | 1.273 | 0.203 | |||

| Gender (covariate) | −2.944 | 1.171 | −2.513 | 0.012 | |||

| Nationality (covariate) | −4.131 | 1.797 | −2.298 | 0.022 | |||

| Educational support (covariate) | −2.301 | 1.139 | −2.018 | 0.044 | |||

| Grade repetition (covariate) | 3.039 | 1.757 | 1.729 | 0.084 |

| Peer Support | Effect | SE | t | p | LLCI | ULCI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 (16th percentile) | 7.723 | 0.941 | 8.203 | <0.001 | 5.873 | 9.573 |

| 3 (50th percentile) | 5.732 | 0.592 | 9.682 | <0.001 | 4.568 | 6.895 |

| 4 (84th percentile) | 4.736 | 0.853 | 5.547 | <0.001 | 3.058 | 6.414 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rodríguez-Rojo, I.C.; García-Sastre, M.; Peñacoba-Puente, C.; Cuesta-Lozano, D.; García-Rodríguez, L.; Blázquez-González, P.; González-Alegre, P.; López-Reina-Roldán, J.M.; Luengo-González, R. From Healthy Eating to Positive Mental Health in Adolescents: A Moderated Mediation Model Involving Stress Management and Peer Support. Nutrients 2025, 17, 3305. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17203305

Rodríguez-Rojo IC, García-Sastre M, Peñacoba-Puente C, Cuesta-Lozano D, García-Rodríguez L, Blázquez-González P, González-Alegre P, López-Reina-Roldán JM, Luengo-González R. From Healthy Eating to Positive Mental Health in Adolescents: A Moderated Mediation Model Involving Stress Management and Peer Support. Nutrients. 2025; 17(20):3305. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17203305

Chicago/Turabian StyleRodríguez-Rojo, Inmaculada C., Montserrat García-Sastre, Cecilia Peñacoba-Puente, Daniel Cuesta-Lozano, Leonor García-Rodríguez, Patricia Blázquez-González, Patricia González-Alegre, Juan Manuel López-Reina-Roldán, and Raquel Luengo-González. 2025. "From Healthy Eating to Positive Mental Health in Adolescents: A Moderated Mediation Model Involving Stress Management and Peer Support" Nutrients 17, no. 20: 3305. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17203305

APA StyleRodríguez-Rojo, I. C., García-Sastre, M., Peñacoba-Puente, C., Cuesta-Lozano, D., García-Rodríguez, L., Blázquez-González, P., González-Alegre, P., López-Reina-Roldán, J. M., & Luengo-González, R. (2025). From Healthy Eating to Positive Mental Health in Adolescents: A Moderated Mediation Model Involving Stress Management and Peer Support. Nutrients, 17(20), 3305. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17203305