Nutritional Status of 8,128,014 Chilean and Immigrant Children and Adolescents Evaluated by the National Board of School Aid and Scholarships (JUNAEB) Between 2013 and 2023

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Database and Sampling

2.2. Nutritional Status

2.3. Sociodemographic Background

2.4. Statistical Analysis

2.5. Ethical Considerations

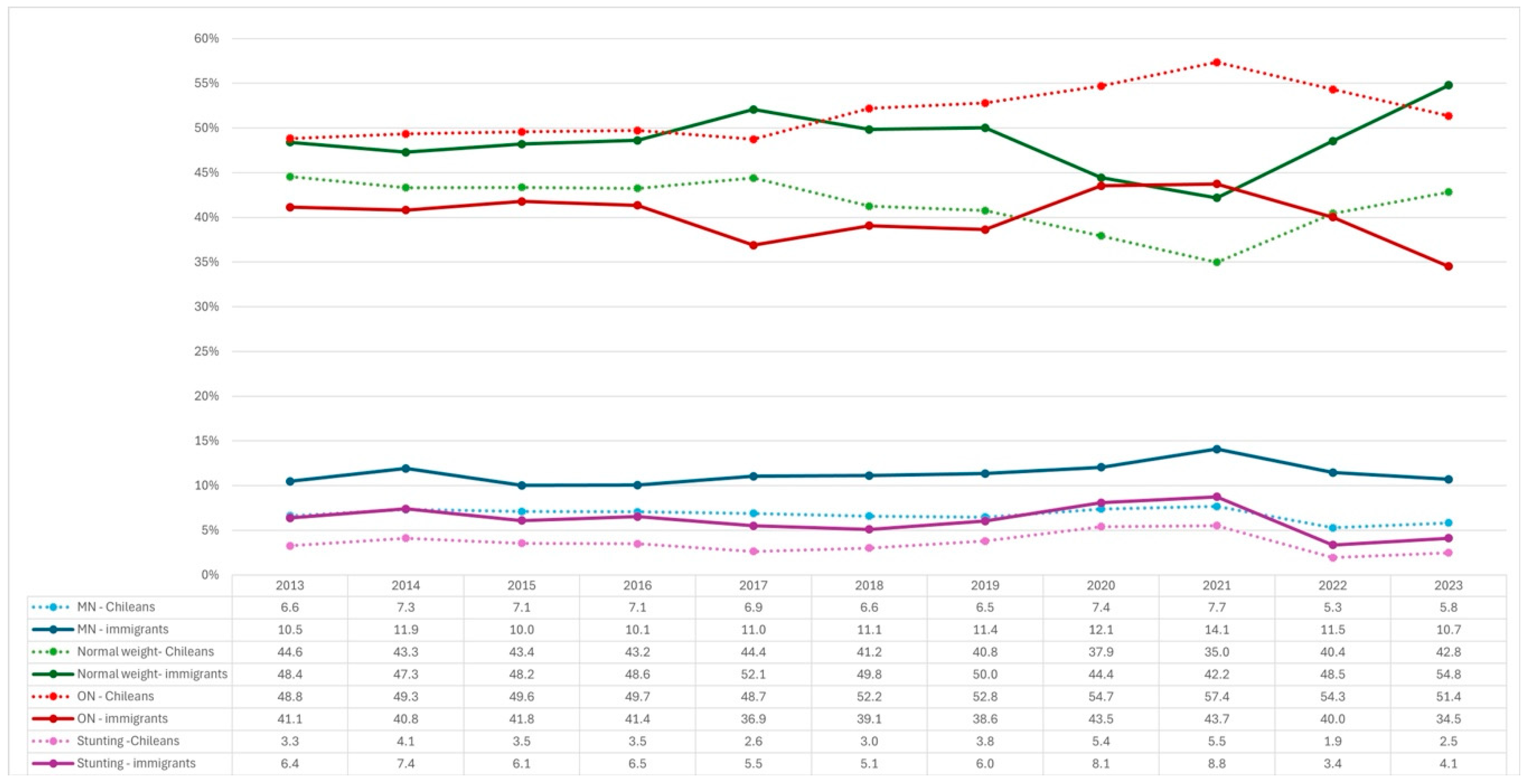

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Corvalán, C.; Garmendia, M.L.; Jones-Smith, J.; Lutter, C.K.; Miranda, J.J.; Pedraza, L.S.; Popkin, B.M.; Ramirez-Zea, M.; Salvo, D.; Stein, A.D. Nutrition Status of Children in Latin America. Obes. Rev. 2017, 18, 7–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kolker, C. Chile Passed Tough Measures to Combat an Obesity Epidemic, so Why Does It Still Have an Obesity Problem? BMJ 2024, 384, q584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bahar, D.; Dooley, M. No Refugees and Migrants Left Behind. In Leave No One Behind: Time for Specifics on the Sustainable Development Goals; Brookings Institution Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Ankomah, A.; Byaruhanga, J.; Woolley, E.; Boamah, S.; Akombi-Inyang, B. Double Burden of Malnutrition among Migrants and Refugees in Developed Countries: A Mixed-Methods Systematic Review. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0273382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abubakar, I.; Aldridge, R.W.; Devakumar, D.; Orcutt, M.; Burns, R.; Barreto, M.L.; Dhavan, P.; Fouad, F.M.; Groce, N.; Guo, Y.; et al. The UCL–Lancet Commission on Migration and Health: The Health of a World on the Move. Lancet 2018, 392, 2606–2654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez, D.J. Children of Immigrants: Health, Adjustment, and Public Assistance. In Children of Immigrants; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Instituto Nacional de Estadísticas; Instituto Nacional de Estadísticas (INE) y El Departamento de Extranjería y Migración (DEM). Chile Informe de Resultados de La Estimación de Personas Extranjeras Residentes En Chile. Available online: https://www.ine.gob.cl/docs/default-source/demografia-y-migracion/publicaciones-y-anuarios/migración-internacional/estimación-población-extranjera-en-chile-2018/estimación-población-extranjera-en-chile-2022-resultados.pdf?sfvrsn=869dce24_4 (accessed on 21 November 2024).

- El Número de Niños, Niñas y Adolescentes En Movimiento En América Latina y El Caribe Alcanza Nuevo Récord, En Medio de La Violencia, Inestabilidad y Cambio Climático. Available online: https://www.unicef.org/es/comunicados-prensa/numero-ninos-ninas-adolescentes-movimiento-america-latina-alcanza-nuevo-record (accessed on 21 November 2024).

- Ministerio de Desarrollo Social y Familia. Programa de Manejo y Seguimiento de Obesidad Infantil. Available online: https://www.dipres.gob.cl/597/articles-212533_doc_pdf1.pdf?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 5 January 2025).

- Mapa Nutricional | Junaeb. Available online: https://www.junaeb.cl/mapa-nutricional/ (accessed on 21 November 2024).

- Biblioteca de Datos Para La Investigación—JUNAEB. Available online: https://bibliotecadatos.sead.junaeb.cl/ (accessed on 21 November 2024).

- WHO Child Growth Standards: Length/Height-for-Age, Weight-for-Age, Weight-for-Length, Weight-for-Height and Body Mass Index-for-Age: Methods and Development. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/924154693X (accessed on 27 November 2024).

- Minsal. Patrones de Crecimiento Para La Evaluación Nutricional de Niños, Niñas y Adolescentes Desde El Nacimiento Hasta Los 19 Años de Edad. 2018. Available online: http://www.bibliotecaminsal.cl/patrones-de-crecimiento-para-la-evaluacion-nutricional-de-ninos-ninas-y-adolescentes-desde-el-nacimiento-hasta-los-19-anos-de-edad/ (accessed on 21 November 2024).

- Tienda, M.; Haskins, R. Immigrant Children: Introducing the Issue. Future Child. 2011, 21, 3–18. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/41229009 (accessed on 22 November 2024). [CrossRef]

- Buhrman, D.Z.; Permashwar, V.; Sridhar, V.; Rahman, M.; Sorayya, A. Addressing Barriers to Healthcare for Refugee and Immigrant Children. Pediatrics 2021, 147, 642–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rada, I.; Oyarte, M.; Cabieses, B. A Comparative Analysis of Health Status of International Migrants and Local Population in Chile: A Population-Based, Cross-Sectional Analysis from a Social Determinants of Health Perspective. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Research Council (US) and Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on the Health and Adjustment of Immigrant Children and Families. Children of Immigrants: Health, Adjustment, and Public Assistance; Hernandez, D.J., Ed.; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1999; ISBN 0309065453.

- Besharat Pour, M.; Bergström, A.; Bottai, M.; Kull, I.; Wickman, M.; Håkansson, N.; Wolk, A.; Moradi, T. Effect of Parental Migration Background on Childhood Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Body Mass Index. J. Obes. 2014, 2014, 406529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lister, N.B.; Baur, L.A.; Felix, J.F.; Hill, A.J.; Marcus, C.; Reinehr, T.; Summerbell, C.; Wabitsch, M. Child and Adolescent Obesity. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2023, 9, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rivera, J.Á.; de Cossío, T.G.; Pedraza, L.S.; Aburto, T.C.; Sánchez, T.G.; Martorell, R. Childhood and Adolescent Overweight and Obesity in Latin America: A Systematic Review. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2014, 2, 321–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popkin, B.M.; Corvalan, C.; Grummer-Strawn, L.M. Dynamics of the Double Burden of Malnutrition and the Changing Nutrition Reality. Lancet 2020, 395, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNICEF-WHO-The World Bank: Joint Child Malnutrition Estimates (JME)—Levels and Trends–2023 Edition-UNICEF DATA. Available online: https://data.unicef.org/resources/jme-report-2023/ (accessed on 21 November 2024).

- Talukdar, R.; Ravel, V.; Barman, D.; Kumar, V.; Dutta, S.; Kanungo, S. Prevalence of Undernutrition among Migrant, Refugee, Internally Displaced Children and Children of Migrated Parents in Lower-Middle-Income Countries: A Meta-Analysis of Published Studies from Last Twelve Years. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Clin. Res. Rev. 2024, 18, 102976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Global Atlas on Childhood Obesity|World Obesity Federation. Available online: https://www.worldobesity.org/membersarea/global-atlas-on-childhood-obesity (accessed on 21 November 2024).

- Solmi, M.; Estradé, A.; Thompson, T.; Agorastos, A.; Radua, J.; Cortese, S.; Dragioti, E.; Leisch, F.; Vancampfort, D.; Thygesen, L.C.; et al. Physical and Mental Health Impact of COVID-19 on Children, Adolescents, and Their Families: The Collaborative Outcomes Study on Health and Functioning during Infection Times-Children and Adolescents (COH-FIT-C&A). J. Affect. Disord. 2022, 299, 367–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bustos-Arriagada, E.; Fuentealba-Urra, S.; Etchegaray-Armijo, K.; Quintana-Aguirre, N.; Castillo-Valenzuela, O. Feeding Behaviour and Lifestyle of Children and Adolescents One Year after Lockdown by the COVID-19 Pandemic in Chile. Nutrients 2021, 13, 4138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, L.N.; Yoshida-Montezuma, Y.; Dewart, N.; Jalil, E.; Khattar, J.; De Rubeis, V.; Carsley, S.; Griffith, L.E.; Mbuagbaw, L. Obesity and Weight Change during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Children and Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Obes. Rev. 2023, 24, e13550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gálvez, P.; Egaña, D.; Rodriguez-Osiac, L. Consecuencias de La Pandemia Por COVID-19: ¿Pasamos de La Obesidad a La Desnutrición? Rev. Chil. De. Nutr. 2021, 48, 479–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etchegaray-Armijo, K.; Fuentealba-Urra, S.; Bustos-Arriagada, E. Factores de Riesgo Asociados al Sobrepeso y Obesidad En Niños y Adolescentes Durante La Pandemia Por COVID-19 En Chile. Rev. Chil. De Nutr. 2023, 50, 56–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Roso, M.B.; de Carvalho Padilha, P.C.; Mantilla-Escalante, D.C.; Ulloa, N.; Brun, P.; Acevedo-Correa, D.; Ferreira Peres, W.A.; Martorell, M.; Aires, M.T.; de Oliveira Cardoso, L.; et al. Covid-19 Confinement and Changes of Adolescent’s Dietary Trends in Italy, Spain, Chile, Colombia and Brazil. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alvarado-Quinteros, A.; Roco Videla, Á. How Much Has the Pandemic Affected the Nutritional Status of Chilean Children? Nutr. Hosp. 2022, 39, 1200–1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- UNICEF-PNUD-OIT. Impactos de La Pandemia En El Bienestar de Los Hogares de Niños, Niñas y Adolescentes En Chile. 2021. Available online: https://www.undp.org/sites/g/files/zskgke326/files/migration/cl/9f797001eab5dc4d2d01f46cba4b100c27b324d42eda160f5a82ad1512b3be85.pdf?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 5 January 2025).

- Hun Gamboa, N.; Salazar, M.; Aliste, S.; Aguilera, C.; Cárdenas, M.E. Food Quality in Pre-School and School Children in Chile during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Nutr. Hosp. 2023, 40, 934–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akombi, B.; Agho, K.; Hall, J.; Wali, N.; Renzaho, A.; Merom, D. Stunting, Wasting and Underweight in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monasta, L.; Lobstein, T.; Cole, T.J.; Vignerová, J.; Cattaneo, A. Defining Overweight and Obesity in Pre-school Children: IOTF Reference or WHO Standard? Obes. Rev. 2011, 12, 295–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Llorca-Colomer, F.; Murillo-Llorente, M.T.; Legidos-García, M.E.; Palau-Ferré, A.; Pérez-Bermejo, M. Differences in Classification Standards For the Prevalence of Overweight and Obesity in Children. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Clin. Epidemiol. 2022, 14, 1031–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phelps, N.H.; Singleton, R.K.; Zhou, B.; Heap, R.A.; Mishra, A.; Bennett, J.E.; Paciorek, C.J.; Lhoste, V.P.; Carrillo-Larco, R.M.; Stevens, G.A.; et al. Worldwide Trends in Underweight and Obesity from 1990 to 2022: A Pooled Analysis of 3663 Population-Representative Studies with 222 Million Children, Adolescents, and Adults. Lancet 2024, 403, 1027–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mölenberg, F.J.M.; Smit, M.S.; Nieboer, D.; Voortman, T.; Jansen, W. The Long-term Effects of a School-based Intervention on Preventing Childhood Overweight: Propensity Score Matching Analysis within the Generation R Study Cohort. Pediatr. Obes. 2025, e13200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- da Silva, E.A.; Pedrozo, E.A.; da Silva, T.N. National School Feeding Program (PNAE): A Public Policy That Promotes a Learning Framework and a More Sustainable Food System in Rio Grande Do Sul, Brazil. Foods 2023, 12, 3622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, D.B.; Podrabsky, M.; Rocha, A.; Otten, J.J. Effect of the Healthy Hunger-Free Kids Act on the Nutritional Quality of Meals Selected by Students and School Lunch Participation Rates. JAMA Pediatr. 2016, 170, e153918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Years | Chileans n (%) | Immigrants n (%) | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2013 | 674,908 (99.6) | 2463 (0.4) | 677,371 |

| 2014 | 751,202 (99.5) | 3940 (0.5) | 755,142 |

| 2015 | 735,529 (99.1) | 6745 (0.9) | 742,274 |

| 2016 | 751,061 (98.7) | 9527 (1.3) | 760,588 |

| 2017 | 786,686 (98.4) | 13,020 (1.6) | 799,706 |

| 2018 | 897,290 (97.0) | 27,405 (3.0) | 924,695 |

| 2019 | 878,040 (95.4) | 42,359 (4.6) | 920,399 |

| 2020 | 699,661 (95.0) | 36,700 (5.0) | 736,361 |

| 2021 | 624,548 (95.1) | 32,480 (4.9) | 657,028 |

| 2022 | 587,387 (93.2) | 43,164 (6.8) | 630,551 |

| 2023 | 482,669 (92.1) | 41,230 (7.9) | 523,899 |

| 7,868,981 | 259,033 | 8,128,014 |

| Nutritional Status | Chileans | Immigrants | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male n (%) | Female n (%) | p | Male n (%) | Female n (%) | p | |

| Thinness | ||||||

| 2013 | 6369 (1.9) | 5461 (1.6) | 0.216 | 49 (3.6) | 27 (2.5) | 0.794 |

| 2014 | 8676 (2.3) | 7653 (2.1) | 0.385 | 98 (4.6) | 63 (3.5) | 0.733 |

| 2015 | 8386 (2.2) | 6810 (1.9) | 0.196 | 105 (2.8) | 86 (2.9) | 0.967 |

| 2016 | 8400 (2.2) | 6985 (1.9) | 0.192 | 177 (3.5) | 142 (3.2) | 0.882 |

| 2017 | 7559 (1.9) | 5929 (1.5) | 0.076 | 240 (3.4) | 208 (3.5) | 0.953 |

| 2018 | 9242 (2.0) | 7761 (1.7) | 0.149 | 512 (3.5) | 409 (3.2) | 0.802 |

| 2019 | 9133 (2.0) | 7768 (1.7) | 0.150 | 759 (3.3) | 617 (3.1) | 0.834 |

| 2020 | 10,440 (2.8) | 8655 (2.4) | 0.084 | 987 (4.9) | 719 (4.4) | 0.629 |

| 2021 | 10,573 (3.1) | 8044 (2.5) | 0.014 | 1155 (6.4) | 722 (5.0) | 0.209 |

| 2022 | 4785 (1.5) | 3476 (1.1) | 0.117 | 676 (2.8) | 387 (2.1) | 0.485 |

| 2023 | 4385 (1.6) | 3411 (1.3) | 0.274 | 669 (2.8) | 409 (2.4) | 0.691 |

| Risk of thinness | ||||||

| 2013 | 17,128 (5.1) | 16,007 (4.7) | 0.092 | 90 (6.5) | 92 (8.5) | 0.608 |

| 2014 | 20,741 (5.4) | 18,469 (4.9) | 0.025 | 182 (8.5) | 126 (7.0) | 0.631 |

| 2015 | 20,091 (5.3) | 17,542 (4.8) | 0.027 | 285 (7.7) | 199 (6.6) | 0.646 |

| 2016 | 20,594 (5.3) | 17,920 (4.8) | 0.025 | 368 (7.2) | 270 (6.1) | 0.583 |

| 2017 | 22,788 (5.6) | 19,278 (4.9) | 0.001 | 570 (8.1) | 419 (7.0) | 0.519 |

| 2018 | 23,911 (5.1) | 21,244 (4.7) | 0.049 | 1165 (7.9) | 960 (7.6) | 0.797 |

| 2019 | 23,302 (5.0) | 21,427 (4.7) | 0.140 | 1859 (8.2) | 1571 (8.0) | 0.830 |

| 2020 | 19,076 (5.1) | 17,851 (4.9) | 0.378 | 1476 (7.3) | 1240 (7.5) | 0.842 |

| 2021 | 17,510 (5.2) | 16,317 (5.1) | 0.677 | 1557 (8.7) | 1139 (7.9) | 0.458 |

| 2022 | 14,300 (4.5) | 12,663 (4.1) | 0.106 | 1845 (7.6) | 1408 (7.5) | 0.914 |

| 2023 | 13,330 (5.0) | 11,438 (4.5) | 0.065 | 2059 (8.5) | 1279 (7.5) | 0.303 |

| Normal weight | ||||||

| 2013 | 141,784 (42.1) | 160,130 (47.0) | 0.001 | 618 (44.8) | 574 (53.0) | 0.004 |

| 2014 | 155,694 (40.8) | 171,606 (45.9) | 0.001 | 967 (45.1) | 896 (49.9) | 0.038 |

| 2015 | 154,630 (41.1) | 167,511 (45.8) | 0.001 | 1663 (44.6) | 1588 (52.6) | 0.001 |

| 2016 | 159,617 (41.3) | 169,748 (45.3) | 0.001 | 2339 (45.7) | 2292 (52.0) | 0.001 |

| 2017 | 174,138 (42.9) | 181,930 (46.3) | 0.001 | 3532 (50.3) | 3248 (54.2) | 0.001 |

| 2018 | 183,960 (39.1) | 199,761 (44.0) | 0.001 | 6982 (47.4) | 6671 (52.7) | 0.001 |

| 2019 | 179,797 (38.5) | 199,176 (44.0) | 0.001 | 10,841 (47.7) | 10,347 (52.7) | 0.001 |

| 2020 | 130,920 (35.0) | 150,734 (41.7) | 0.001 | 8336 (41.4) | 7968 (48.2) | 0.001 |

| 2021 | 109,806 (32.4) | 122,391 (38.5) | 0.001 | 7173 (40.0) | 6528 (45.1) | 0.001 |

| 2022 | 124,882 (39.0) | 135,801 (43.8) | 0.001 | 12,585 (51.6) | 10,545 (56.2) | 0.001 |

| 2023 | 111,207 (41.7) | 118,058 (45.9) | 0.001 | 12,717 (52.7) | 9868 (57.8) | 0.001 |

| Overweight | ||||||

| 2013 | 95,384 (28.3) | 97,120 (28.5) | 0.330 | 381 (27.6) | 265 (24.5) | 0.378 |

| 2014 | 106,398 (27.9) | 104,773 (28.0) | 0.608 | 504 (23.5) | 451 (25.1) | 0.564 |

| 2015 | 105,441 (28.0) | 104,280 (28.5) | 0.011 | 1009 (27.1) | 754 (25.0) | 0.321 |

| 2016 | 106,498 (27.6) | 106,967 (28.6) | 0.001 | 1296 (25.3) | 1071 (24.3) | 0.575 |

| 2017 | 109,721 (27.0) | 111,882 (28.5) | 0.001 | 1657 (23.6) | 1403 (23.4) | 0.896 |

| 2018 | 132,088 (28.1) | 134,019 (29.5) | 0.001 | 3562 (24.2) | 3093 (24.4) | 0.849 |

| 2019 | 131,546 (28.1) | 132,343 (29.2) | 0.001 | 5556 (24.4) | 4714 (24.0) | 0.637 |

| 2020 | 105,878 (28.3) | 105,590 (29.2) | 0.001 | 5210 (25.9) | 4173 (25.2) | 0.440 |

| 2021 | 88,218 (26.0) | 85,747 (27.0) | 0.001 | 3918 (21.8) | 3342 (23.1) | 0.185 |

| 2022 | 83,215 (26.0) | 85,836 (27.7) | 0.001 | 5467 (22.4) | 4313 (23.0) | 0.481 |

| 2023 | 69,182 (25.9) | 70,608 (27.5) | 0.001 | 5344 (22.1) | 3890 (22.8) | 0.425 |

| Obesity | ||||||

| 2013 | 51,336 (15.3) | 46,576 (13.7) | 0.001 | 170 (12.3) | 88 (8.1) | 0.304 |

| 2014 | 59,132 (15.5) | 51,903 (13.9) | 0.001 | 268 (12.5) | 183 (10.2) | 0.453 |

| 2015 | 59,145 (15.7) | 51,992 (14.2) | 0.001 | 454 (12.2) | 311 (10.3) | 0.417 |

| 2016 | 61,097 (15.8) | 54,351 (14.5) | 0.001 | 675 (13.2) | 486 (11.0) | 0.259 |

| 2017 | 62,454 (15.4) | 55,484 (14.1) | 0.001 | 696 (9.9) | 526 (8.8) | 0.514 |

| 2018 | 84,817 (18.0) | 70,930 (15.6) | 0.001 | 1848 (12.5) | 1215 (9.6) | 0.013 |

| 2019 | 86,205 (18.4) | 70,400 (15.6) | 0.001 | 2732 (12.0) | 1887 (9.6) | 0.010 |

| 2020 | 72,866 (19.5) | 58,135 (16.1) | 0.001 | 2899 (14.4) | 1795 (10.9) | 0.001 |

| 2021 | 69,378 (20.5) | 57,285 (18.0) | 0.001 | 2633 (14.6) | 1878 (13.0) | 0.126 |

| 2022 | 60,683 (18.9) | 52,590 (17.0) | 0.001 | 2797 (11.5) | 1675 (8.9) | 0.006 |

| 2023 | 48,739 (18.3) | 42,004 (16.3) | 0.001 | 2565 (10.6) | 1393 (8.2) | 0.015 |

| Severe obesity | ||||||

| 2013 | 24,621 (7.3) | 15,455 (4.5) | 0.001 | 72 (5.2) | 37 (3.4) | 0.670 |

| 2014 | 30,720 (8.1) | 19,377 (5.2) | 0.001 | 124 (5.8) | 78 (4.3) | 0.640 |

| 2015 | 28,689 (7.2) | 17,757 (4.9) | 0.001 | 210 (5.6) | 81 (2.7) | 0.299 |

| 2016 | 29,983 (7.8) | 18,428 (4.9) | 0.001 | 266 (5.2) | 145 (3.3) | 0.376 |

| 2017 | 29,724 (7.3) | 18,819 (4.8) | 0.001 | 333 (4.7) | 188 (3.1) | 0.377 |

| 2018 | 36,142 (7.7) | 20,820 (4.6) | 0.001 | 673 (4.6) | 315 (2.5) | 0.113 |

| 2019 | 37,624 (8.1) | 21,678 (4.8) | 0.001 | 991 (4.4) | 485 (2.5) | 0.072 |

| 2020 | 35,398 (9.5) | 20,818 (5.8) | 0.001 | 1250 (6.2) | 647 (3.9) | 0.035 |

| 2021 | 43,703 (12.9) | 28,056 (8.8) | 0.001 | 1561 (8.7) | 874 (6.0) | 0.016 |

| 2022 | 32,626 (10.2) | 19,694 (6.4) | 0.001 | 1045 (4.3) | 421 (2.3) | 0.067 |

| 2023 | 20,019 (7.5) | 11,518 (4.5) | 0.001 | 790 (3.3) | 247 (1.5) | 0.139 |

| Stunting | ||||||

| 2013 | 11,709 (3.5) | 10,489 (3.1) | 0.096 | 109 (7.9) | 48 (4.4) | 0.423 |

| 2014 | 16,446 (4.3) | 14,736 (3.9) | 0.075 | 152 (7.1) | 139 (7.7) | 0.845 |

| 2015 | 14,355 (3.8) | 12,125 (3.3) | 0.028 | 251 (6.7) | 160 (5.3) | 0.564 |

| 2016 | 14,300 (3.7) | 12,454 (3.3) | 0.076 | 365 (7.1) | 256 (5.8) | 0.519 |

| 2017 | 11,105 (2.7) | 10,322 (2.6) | 0.648 | 412 (5.9) | 304 (5.1) | 0.644 |

| 2018 | 14,012 (3.0) | 14,366 (3.2) | 0.332 | 730 (5.0) | 663 (5.3) | 0.800 |

| 2019 | 17,485 (3.7) | 18,364 (4.1) | 0.050 | 1348 (5.9) | 1209 (6.2) | 0.750 |

| 2020 | 21,179 (5.7) | 19,588 (5.4) | 0.186 | 1658 (8.2) | 1308 (7.9) | 0.765 |

| 2021 | 19,813 (5.8) | 17,554 (5.5) | 0.210 | 1636 (9.1) | 1205 (8.3) | 0.456 |

| 2022 | 6352 (2.0) | 6425 (2.1) | 0.690 | 890 (3.7) | 554 (3.0) | 0.477 |

| 2023 | 6804 (2.6) | 6936 (2.7) | 0.715 | 1041 (4.3) | 657 (3.9) | 0.687 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bustos-Arriagada, E.; Vásquez, F.; Etchegaray-Armijo, K.; López-Arana, S. Nutritional Status of 8,128,014 Chilean and Immigrant Children and Adolescents Evaluated by the National Board of School Aid and Scholarships (JUNAEB) Between 2013 and 2023. Nutrients 2025, 17, 327. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17020327

Bustos-Arriagada E, Vásquez F, Etchegaray-Armijo K, López-Arana S. Nutritional Status of 8,128,014 Chilean and Immigrant Children and Adolescents Evaluated by the National Board of School Aid and Scholarships (JUNAEB) Between 2013 and 2023. Nutrients. 2025; 17(2):327. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17020327

Chicago/Turabian StyleBustos-Arriagada, Edson, Fabián Vásquez, Karina Etchegaray-Armijo, and Sandra López-Arana. 2025. "Nutritional Status of 8,128,014 Chilean and Immigrant Children and Adolescents Evaluated by the National Board of School Aid and Scholarships (JUNAEB) Between 2013 and 2023" Nutrients 17, no. 2: 327. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17020327

APA StyleBustos-Arriagada, E., Vásquez, F., Etchegaray-Armijo, K., & López-Arana, S. (2025). Nutritional Status of 8,128,014 Chilean and Immigrant Children and Adolescents Evaluated by the National Board of School Aid and Scholarships (JUNAEB) Between 2013 and 2023. Nutrients, 17(2), 327. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17020327