Alpha-Gal Syndrome in the Heartland: Dietary Restrictions, Public Awareness, and Systemic Barriers in Rural Kansas

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Participants

2.2. Survey Development

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

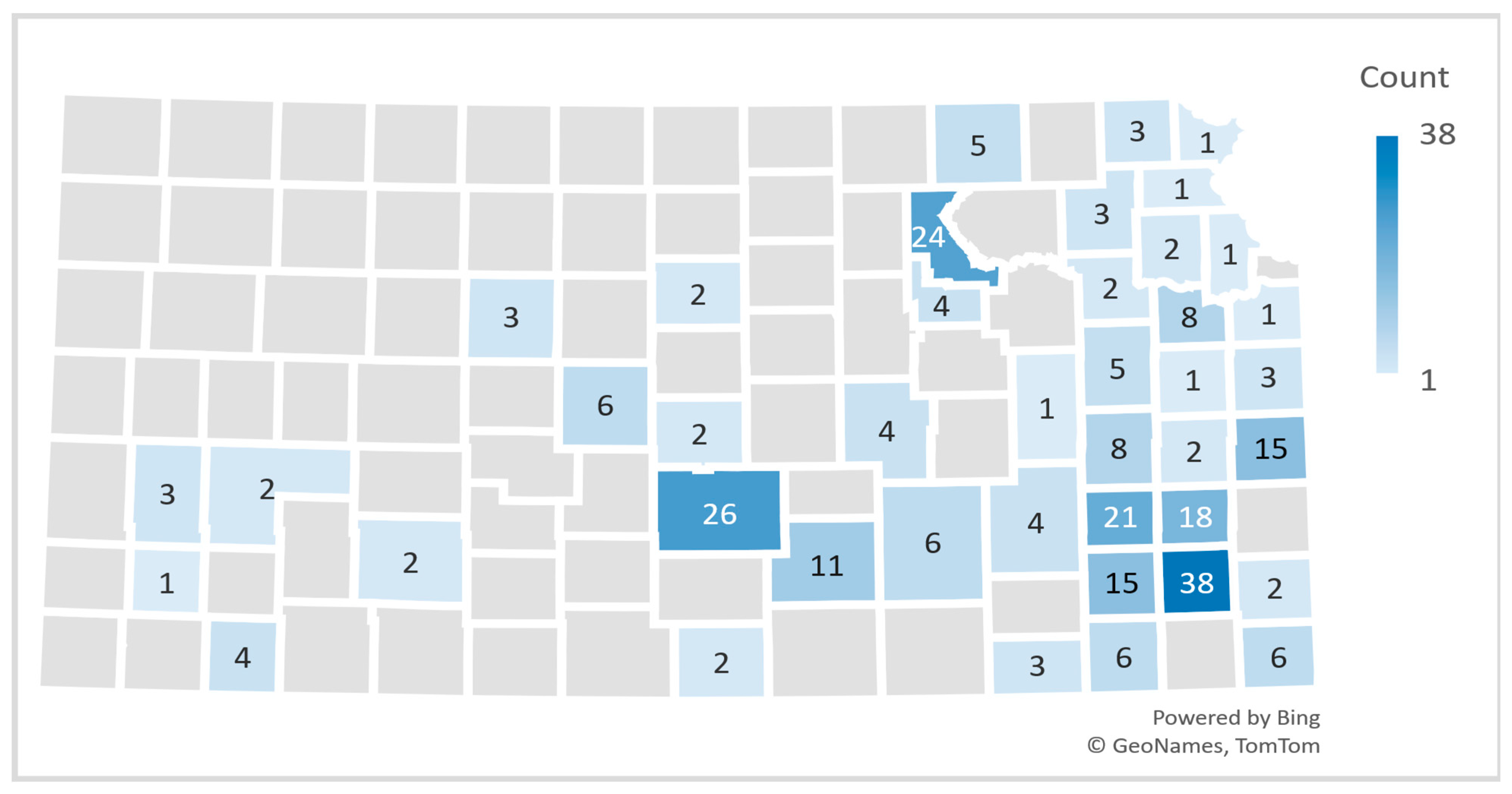

3.1. Participant Characteristics

3.1.1. Extension Professionals

3.1.2. Kansas Community Participants

3.2. Participants’ Knowledge and Awareness of AGS

3.2.1. Extension Professionals

3.2.2. Kansas Community Participants

3.3. Participants’ Perceived Impact of AGS on Individuals

3.3.1. Dietary Restrictions

Extension Professionals

Kansas Community Participants

3.3.2. Health Impact

Extension Professionals

Kansas Community Participants

3.3.3. Social and Financial Impact

Extension Professionals

Kansas Community Participants

3.4. Perceived Knowledge Gaps and Their Impact on AGS Management

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AGS | Alpha-gal syndrome |

| IgE | Immunoglobulin E |

| NSAIDS | Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs |

| KDHE | Kansas Department of Health and Environment |

References

- Commins, S.P.; James, H.R.; Kelly, L.A.; Pochan, S.L.; Workman, L.J.; Perzanowski, M.S.; Kocan, K.M.; Fahy, J.V.; Nganga, L.W.; Ronmark, E.; et al. The relevance of tick bites to the production of IgE antibodies to the mammalian oligosaccharide galactose-α-1,3-galactose. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2011, 127, 1286–1293.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, S.; Yi, L.; Shields, B.; Platts-Mills, T.; Wilson, J.; Flowers, R.H. Alpha-gal syndrome: A review for the dermatologist. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2023, 89, 750–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mollah, F.; Zacharek, M.A.; Benjamin, M.R. What Is Alpha-Gal Syndrome? JAMA 2024, 331, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, J.M.; Erickson, L.; Levin, M.; Ailsworth, S.M.; Commins, S.P.; Platts-Mills, T.A.E. Tick bites, IgE to galactose-alpha-1,3-galactose and urticarial or anaphylactic reactions to mammalian meat: The alpha-gal syndrome. Allergy 2024, 79, 1440–1454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Commins, S.P.; Satinover, S.M.; Hosen, J.; Mozena, J.; Borish, L.; Lewis, B.D.; Woodfolk, J.A.; Platts-Mills, T.A. Delayed anaphylaxis, angioedema, or urticaria after consumption of red meat in patients with IgE antibodies specific for galactose-alpha-1,3-galactose. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2009, 123, 426–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Commins, S.P.; Platts-Mills, T.A. Delayed anaphylaxis to red meat in patients with IgE specific for galactose alpha-1,3-galactose (alpha-gal). Curr. Allergy Asthma Rep. 2013, 13, 72–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neil, B.H.; Allen, R.; Spigel, D.R.; Stinchcombe, T.E.; Moore, D.T.; Berlin, J.D.; Goldberg, R.M. High incidence of cetuximab-related infusion reactions in Tennessee and North Carolina and the association with atopic history. J. Clin. Oncol. 2007, 25, 3644–3648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, C.H.; Mirakhur, B.; Chan, E.; Le, Q.T.; Berlin, J.; Morse, M.; Murphy, B.A.; Satinover, S.M.; Hosen, J.; Mauro, D.; et al. Cetuximab-induced anaphylaxis and IgE specific for galactose-alpha-1,3-galactose. N. Engl. J. Med. 2008, 358, 1109–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Nunen, S.A.; O’Connor, K.S.; Clarke, L.R.; Boyle, R.X.; Fernando, S.L. An association between tick bite reactions and red meat allergy in humans. Med. J. Aust. 2009, 190, 510–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamsten, C.; Tran, T.A.T.; Starkhammar, M.; Brauner, A.; Commins, S.P.; Platts-Mills, T.A.E.; van Hage, M. Red meat allergy in Sweden: Association with tick sensitization and B-negative blood groups. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2013, 132, 1431–1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keleş, Ş.; Gündüz, M. Alpha gal specific IgE positivity due to tick bites and red meat allergy: The first case report in Turkey. Turk. J. Pediatr. 2019, 61, 615–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabezas-Cruz, A.; Hodžić, A.; Román-Carrasco, P.; Mateos-Hernández, L.; Duscher, G.G.; Sinha, D.K.; Hemmer, W.; Swoboda, I.; Estrada-Peña, A.; de la Fuente, J. Environmental and Molecular Drivers of the α-Gal Syndrome. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakagawa, Y.; Chinuki, Y.; Ogino, R.; Yamasaki, K.; Aiba, S.; Ugajin, T.; Yokozeki, H.; Kitamura, K.; Morita, E. Cohort study of subclinical sensitization against galactose-α-1,3-galactose in Japan: Prevalence and regional variations. J. Dermatol. 2022, 49, 1268–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villalta, D.; Pantarotto, L.; Da Re, M.; Conte, M.; Sjolander, S.; Borres, M.P.; Martelli, P. High prevalence of sIgE to Galactose-α-1,3-galactose in rural pre-Alps area: A cross-sectional study. Clin. Exp. Allergy 2016, 46, 377–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binder, A.M.; Commins, S.P.; Altrich, M.L.; Wachs, T.; Biggerstaff, B.J.; Beard, C.B.; Petersen, L.R.; Kersh, G.J.; Armstrong, P.A. Diagnostic testing for galactose-alpha-1,3-galactose, United States, 2010 to 2018. Ann. Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2021, 126, 411–416.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crispell, G.; Commins, S.P.; Archer-Hartman, S.A.; Choudhary, S.; Dharmarajan, G.; Azadi, P.; Karim, S. Discovery of Alpha-Gal-Containing Antigens in North American Tick Species Believed to Induce Red Meat Allergy. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raghavan, R.K.; Peterson, A.T.; Cobos, M.E.; Ganta, R.; Foley, D. Current and Future Distribution of the Lone Star Tick, Amblyomma americanum (L.) (Acari: Ixodidae) in North America. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0209082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Commins, S.P. Diagnosis & management of alpha-gal syndrome: Lessons from 2,500 patients. Expert Rev. Clin. Immunol. 2020, 16, 667–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Commins, S.P.; James, H.R.; Stevens, W.; Pochan, S.L.; Land, M.H.; King, C.; Mozzicato, S.; Platts-Mills, T.A. Delayed clinical and ex vivo response to mammalian meat in patients with IgE to galactose-alpha-1,3-galactose. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2014, 134, 108–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mabelane, T.; Ogunbanjo, G.A. Ingestion of mammalian meat and alpha-gal allergy: Clinical relevance in primary care. Afr. J. Prim. Health Care Fam. Med. 2019, 11, e1–e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macdougall, J.D.; Thomas, K.O.; Iweala, O.I. The Meat of the Matter: Understanding and Managing Alpha-Gal Syndrome. ImmunoTargets Ther. 2022, 11, 37–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Alpha-Gal Syndrome. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/alpha-gal-syndrome/about/index.html (accessed on 24 September 2024).

- McGill, S.K.; Hashash, J.G.; Platts-Mills, T.A. AGA Clinical Practice Update on Alpha-Gal Syndrome for the GI Clinician: Commentary. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2023, 21, 891–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpenter, A.; Drexler, N.A.; McCormick, D.W.; Thompson, J.M.; Kersh, G.; Commins, S.P.; Salzer, J.S. Health Care Provider Knowledge Regarding Alpha-gal Syndrome—United States, March–May 2022. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2023, 72, 809–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, J.M.; Carpenter, A.; Kersh, G.J.; Wachs, T.; Commins, S.P.; Salzer, J.S. Geographic Distribution of Suspected Alpha-gal Syndrome Cases—United States, January 2017–December 2022. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2023, 72, 815–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eysenbach, G. Improving the quality of Web surveys: The Checklist for Reporting Results of Internet E-Surveys (CHERRIES). J. Med. Internet Res. 2004, 6, e34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Elm, E.; Altman, D.G.; Egger, M.; Pocock, S.J.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Vandenbroucke, J.P.; STROBE Initiative. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2008, 61, 344–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qualtrics. Fraud Detection in Qualtrics. Qualtrics. Available online: https://www.qualtrics.com/support/survey-platform/survey-module/survey-checker/fraud-detection/ (accessed on 31 March 2025).

- Kansas Department of Health and Environment. Alpha-Gal Syndrome. Kansas Department of Health and Environment. Available online: https://maps.kdhe.ks.gov/kstbdec/?page=Alpha-gal-Syndrome (accessed on 24 March 2025).

- Kansas Department of Health and Environment. Ehrlichiosis. Kansas Department of Health and Environment. Available online: https://maps.kdhe.ks.gov/kstbd/?page=Ehrlichiosis&views=Geo-Distribution-Map-%2CGeo-Distribution-Map----%2CTick-Surveillance-Map (accessed on 24 March 2025).

- Ross, M.; Daley, G.; Burnard, M.L.; Sen, A.; Beyene, E.; Bisrat, M.; Zinabu, S.W.; Abrie, M.; Michael, M. Alpha-Gal on the Rise: The Alarming Growth of Alpha-Gal Syndrome in High-Risk Regions. Cureus 2025, 17, e88415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mateo Borrega, M.B.; Garcia, B.; Larramendi, C.H.; Azofra, J.; González Mancebo, E.; Alvarado, M.I.; Alonso Díaz de Durana, M.D.; Núñez Orjales, R.; Diéguez, M.C.; Guilarte, M.; et al. IgE-Mediated Sensitization to Galactose-α-1,3-Galactose (α-Gal) in Urticaria and Anaphylaxis in Spain: Geographical Variations and Risk Factors. J. Investig. Allergol. Clin. Immunol. 2019, 29, 436–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chinuki, Y.; Ishiwata, K.; Yamaji, K.; Takahashi, H.; Morita, E. Haemaphysalis longicornis tick bites are a possible cause of red meat allergy in Japan. Allergy 2016, 71, 421–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Quintela, A.; Dam Laursen, A.S.; Vidal, C.; Skaaby, T.; Gude, F.; Linneberg, A. IgE antibodies to alpha-gal in the general adult population: Relationship with tick bites, atopy, and cat ownership. Clin. Exp. Allergy 2014, 44, 1061–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linneberg, A.; Nielsen, N.H.; Madsen, F.; Frølund, L.; Dirksen, A.; Jørgensen, T. Pets in the home and the development of pet allergy in adulthood. The Copenhagen Allergy Study. Allergy 2003, 58, 21–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Custovic, A.; Simpson, B.M.; Simpson, A.; Hallam, C.L.; Marolia, H.; Walsh, D.; Campbell, J.; Woodcock, A.; National Asthma Campaign Manchester Asthma Allergy Study Group. Current mite, cat, and dog allergen exposure, pet ownership, and sensitization to inhalant allergens in adults. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2003, 111, 402–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Commins, S.P.; Kelly, L.A.; Rönmark, E.; James, H.R.; Pochan, S.L.; Peters, E.J.; Lundbäck, B.; Nganga, L.W.; Cooper, P.J.; Hoskins, J.M.; et al. Galactose-α-1,3-galactose-specific IgE is associated with anaphylaxis but not asthma. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2012, 185, 723–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.S.; Straesser, M.D.; Keshavarz, B.; Workman, L.; McGowan, E.C.; Platts-Mills, T.A.E.; Wilson, J.M. IgE to galactose-α-1,3-galactose wanes over time in patients who avoid tick bites. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 2020, 8, 364–367.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iweala, O.I.; Choudhary, S.K.; Commins, S.P. Food Allergy. Curr. Gastroenterol. Rep. 2018, 20, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Commins, S.P. Invited Commentary: Alpha-Gal Allergy: Tip of the Iceberg to a Pivotal Immune Response. Curr. Allergy Asthma Rep. 2016, 16, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sempa, J.; Brenes, P.; Whitehair, K.; Hobbs, L.; Kidd, T. Decoding Health Professionals’ Attitudes and Perceptions Towards Plant-Based Nutrition: A Narrative Review. Nutrients 2025, 17, 2095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Auria, E.; Abrahams, M.; Zuccotti, G.V.; Venter, C. Personalized Nutrition Approach in Food Allergy: Is It Prime Time Yet? Nutrients 2019, 11, 359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mofidi, S. Nutritional management of pediatric food hypersensitivity. Pediatrics 2003, 111 (Suppl. S3), 1645–1653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santangelo, C.M.; McCloud, E. Nutritional management of children who have food allergies and eosinophilic esophagitis. Immunol. Allergy Clin. N. Am. 2009, 29, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaz-Rodrigues, R.; Mazuecos, L.; de la Fuente, J. Current and future strategies for the diagnosis and treatment of the alpha-gal syndrome (AGS). J. Asthma Allergy 2022, 15, 957–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, X.L.; Sebaratnam, D.F. Mammalian meat allergy. Int. J. Dermatol. 2018, 57, 1433–1436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venter, C.; Meyer, R. Session 1: Allergic disease: The challenges of managing food hypersensitivity. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2010, 69, 11–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedberg, C.; Kaler, A.; Bell, M. P110 knowledge and perceptions of alpha-gal syndrome among primary care physicians in Arkansas 8166. Ann. Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2021, 127, S42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carson, D.A.; Kopsco, H.; Gronemeyer, P.; Mateus-Pinilla, N.; Smith, G.S.; Sandstrom, E.N.; Smith, R.L. Knowledge, attitudes, and practices of Illinois medical professionals related to ticks and tick-borne disease. One Health 2022, 15, 100424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Extension Professionals (n = 144) | Community Participants (n = 138) | |

|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | n (%) | n (%) |

| Age | ||

| 18–29 years | 35 (24) | 15 (11) |

| 30–47 years | 59 (41) | 43 (31) |

| 48–59 years | 29 (20) | 28 (20) |

| 60+ years | 19 (13) | 52 (38) |

| Choose not to provide | 2 (1) | - |

| Estimated mean age | 41.5 | 50.1 |

| Gender | ||

| Female | 104 (72) | 87 (63) |

| Male | 37 (26) | 50 (36) |

| Choose not to provide | 3 (2) | 1 (1) |

| Race | ||

| White or Caucasian | 134 (93) | 124 (90) |

| Black or African American | - | 9 (7) |

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 2 (1) | 2 (1) |

| Asian | 2 (1) | 1 (1) |

| Native Hawaiian/Pacific islander | - | 1 (1) |

| Two or more races | 3 (2) | - |

| Choose not to provide | 3 (2) | 1 (1) |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Non-Latino/Hispanic | 133 (93) | 115 (89) |

| Latino/Hispanic | 4 (3) | 6 (5) |

| Choose not to provide | 6 (4) | 9 (7) |

| AGS status | ||

| Currently has AGS | 7 (5) | 75 (56) |

| Doesn’t have AGS | 117 (87) | 53 (40) |

| Doesn’t know | 10 (8) | 6 (5) |

| Pet ownership | ||

| Has at least one pet | - | 105 (79) |

| Doesn’t have pets | - | 28 (21) |

| Predictor | B | Wald | p | OR (Exp (B)) | 95% CI for OR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1: Pet ownership | |||||

| Pet ownership | 1.23 | 7.44 | 0.006 | 3.43 | (1.42, 8.32) |

| Model 2: Time outdoors | |||||

| Time spent outdoors | 0.87 | 3.54 | 0.060 | 2.39 | (0.97, 5.90) |

| Predictor | B (Pet Model) | OR (95% CI) (Pet Model) | p (Pet Model) | B (Outdoor Model) | OR (95% CI) (Outdoor Model) | p (Outdoor Model) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pet ownership | 1.40 | 4.04 (1.57, 10.41) | 0.004 | - | - | - |

| Time spent Outdoors | - | - | - | 0.74 | 2.11 (0.81, 5.49) | 0.128 |

| Age (1) | 0.54 | 1.72 (0.49, 6.05) | 0.399 | −0.16 | 0.86 (0.18, 4.11) | 0.845 |

| Age (2) | 0.51 | 1.67 (0.44, 6.36) | 0.455 | −0.26 | 0.77 (0.14, 4.25) | 0.768 |

| Age (3) | 0.92 | 2.50 (0.72, 8.66) | 0.147 | −0.39 | 0.67 (0.14, 3.18) | 0.618 |

| Gender (1) | −0.73 | 0.48 (0.22, 1.05) | 0.065 | −0.67 | 0.51 (0.19, 1.32) | 0.165 |

| Extension Professionals (n = 144) | Community Participants (n = 138) | |

|---|---|---|

| Question | n (%) | n (%) |

| Knowledge of AGS | ||

| Yes | 127 (91) | 130 (95) |

| No | 13 (9) | 7 (5) |

| Knowledge of AGS cause (tick bite) | ||

| Yes | 123 (88) | 129 (96) |

| No | 17 (12) | 6 (4) |

| Familiarity with AGS symptoms | ||

| Yes | 64 (46) | 120 (88) |

| No | 59 (42) | 15 (11) |

| Don’t know | 17 (12) | 1 (1) |

| Reported known symptoms * | ||

| Abdominal pain | 47 (64) | 84 (67) |

| Hives | 46 (62) | 84 (67) |

| Diarrhea | 45 (61) | 80 (64) |

| Nausea | 54 (73) | 78 (63) |

| Vomiting | 42 (57) | 56 (45) |

| Heartburn or indigestion | 17 (23) | 48 (39) |

| Itching | 33 (45) | 79 (64) |

| Swelling of the lips | 39 (53) | 77 (62) |

| Shortness of breath | 32 (43) | 60 (48) |

| Cough | 12 (16) | 44 (35) |

| Wheezing | 16 (22) | 40 (32) |

| People you know are diagnosed with AGS | ||

| Knows at least one person | 67 (54) | 106 (84) |

| How did you find out they had AGS | ||

| Friends | 32 (51) | 31 (28) |

| Respondent has AGS | 4 (6) | 36 (32) |

| Family | 6 (9) | 25 (23) |

| Programming | 8 (13) | - |

| Word of mouth | 6 (10) | - |

| Church | 1 (2) | 4(4) |

| Social media | 5 (8) | 2 (2) |

| School | 1 (2) | - |

| Work | - | 6 (5) |

| The person with AGS told them | - | 5 (5) |

| How many people do you know who have recovered from AGS | ||

| None | 50 (82) | 83 (76) |

| One person | 10 (16) | 15 (14) |

| More than one person | 1 (2) | 12 (10) |

| Think that not enough information is available on AGS | ||

| Yes | 2 (2) | 2 (2) |

| No | 89 (65) | 119 (89) |

| Not sure | 45 (33) | 13 (10) |

| Interest in receiving AGS information | ||

| Yes | 107 (80) | 101 (75) |

| No | 27 (20) | 20 (15) |

| Not sure | - | 13 (10) |

| Theme | Representative Quote |

|---|---|

| Emotional and Psychological impact | “This was traumatizing, the first time I went grocery shopping, I sat on the floor in the store and cried because I couldn’t find food that I knew would be safe.” |

| “They all seem to be very frustrated with having to alter their food habits.” | |

| “High anxiety over eating at restaurants or any sort of shared meals, frustration over high amounts of hidden mammal byproducts in many foods and people’s lack of understanding.” | |

| Dietary Challenges | “Eventually I learned and so now I eat mostly chicken and turkey. I use almond milk, plant butter, and check ingredients of everything I buy.” |

| “They are finding unique foods that are helping them that weren’t on their radar or mine before.” | |

| “It has definitely been a challenge for my son. He is nine and struggles with not being able to eat what his friends and family do.” | |

| Health impact and System barriers | “Even with restricting mammalian meat and dairy from my diet, I continue to have allergic reactions… My doctor suspects that I have Mast Cell Activation syndrome…” |

| “I was on Dupixent, it helped, but insurance no longer covers it.” | |

| “There is very little that doctors know about it… doctors don’t believe me when I tell them… seem to lack an understanding of what a mammal is.” | |

| “Doctors need to be educated! There needs to be access to the test!” | |

| “No, I have not seen any information on how to treat or manage AGS.” | |

| “I believe that there is much misinformation… but reputable sources lack good information…” | |

| “I was treated with lots of skepticism after a full anaphylactic ER visit…” | |

| “I do not know of any educational resources in my community. My information is from researching the condition online.” | |

| Social and Financial impact | “One friend raises cattle, they still do but have added emu to their operation.” |

| “As a beef producer, one was devastated.” | |

| “It was hard for everyone I know, especially since beef is such a large part of most Kansas diets.” | |

| “Churches need more info on special diets especially alpha-gal-friendly diets.” | |

| “I think more people should be aware, especially in the restaurant industry.” | |

| “I purchased entirely new dishes, pots and pans, silverware, etc., for my kitchen to avoid the possibilities of cross-contamination.” | |

| “Food is more expensive and harder to find.” | |

| “I always have an EpiPen at home and at work… but insurance wouldn’t cover it.” |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sempa, J.; Brenes, P.; Tegeler, A.; Looper, J.; Chao, M.; Park, Y. Alpha-Gal Syndrome in the Heartland: Dietary Restrictions, Public Awareness, and Systemic Barriers in Rural Kansas. Nutrients 2025, 17, 3043. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17193043

Sempa J, Brenes P, Tegeler A, Looper J, Chao M, Park Y. Alpha-Gal Syndrome in the Heartland: Dietary Restrictions, Public Awareness, and Systemic Barriers in Rural Kansas. Nutrients. 2025; 17(19):3043. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17193043

Chicago/Turabian StyleSempa, Judith, Priscilla Brenes, Alexandra Tegeler, Jordan Looper, Michael Chao, and Yoonseong Park. 2025. "Alpha-Gal Syndrome in the Heartland: Dietary Restrictions, Public Awareness, and Systemic Barriers in Rural Kansas" Nutrients 17, no. 19: 3043. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17193043

APA StyleSempa, J., Brenes, P., Tegeler, A., Looper, J., Chao, M., & Park, Y. (2025). Alpha-Gal Syndrome in the Heartland: Dietary Restrictions, Public Awareness, and Systemic Barriers in Rural Kansas. Nutrients, 17(19), 3043. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17193043