The Longitudinal Influence of Parent–Grandparent Coparenting Relationships on Preschoolers’ Eating Behaviors in Chinese Urban Families: The Mediating Roles of Caregivers’ Feeding Behaviors

Abstract

1. Introduction

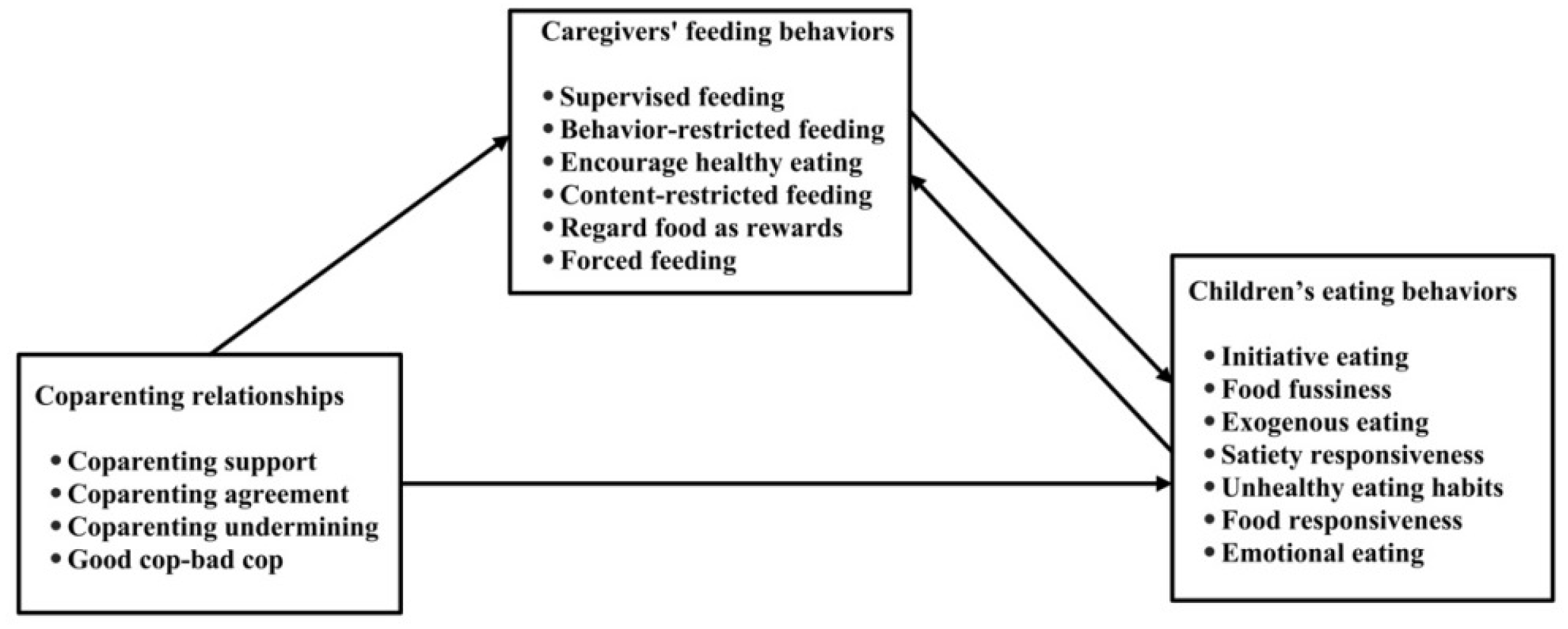

1.1. Intergenerational Coparenting and Child Eating Behaviors

1.2. Theoretical Framework and Hypotheses

2. Methods

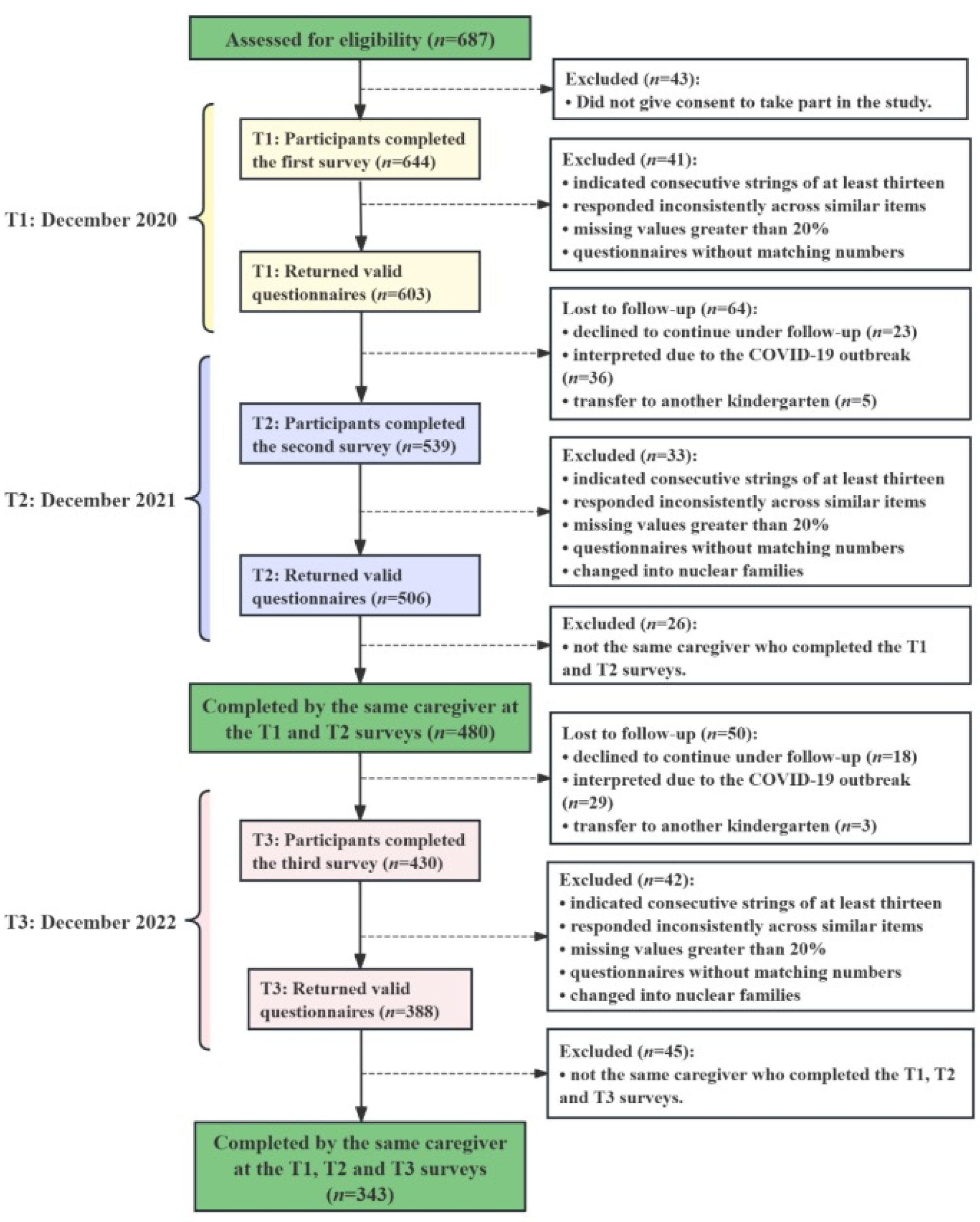

2.1. Study Population

2.2. Procedure

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Sociodemographic Information

2.3.2. Anthropometric Measurement

2.3.3. Parent–Grandparent Coparenting Relationships

2.3.4. Caregivers’ Feeding Behaviors

2.3.5. Preschool Children’s Eating Behaviors

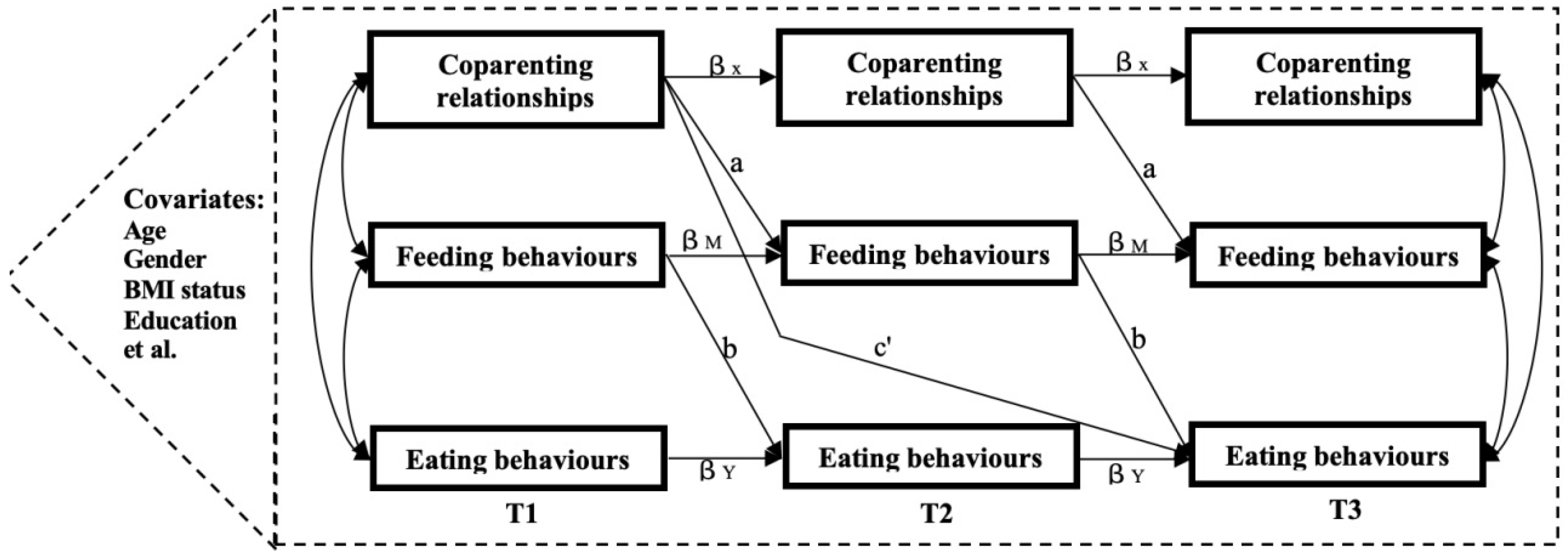

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Demographic Characteristics of the Sample

3.2. The Characteristics of Parent–Grandparent Coparenting, Caregivers’ Feeding Behaviors and Preschool Children’s Eating Behaviors

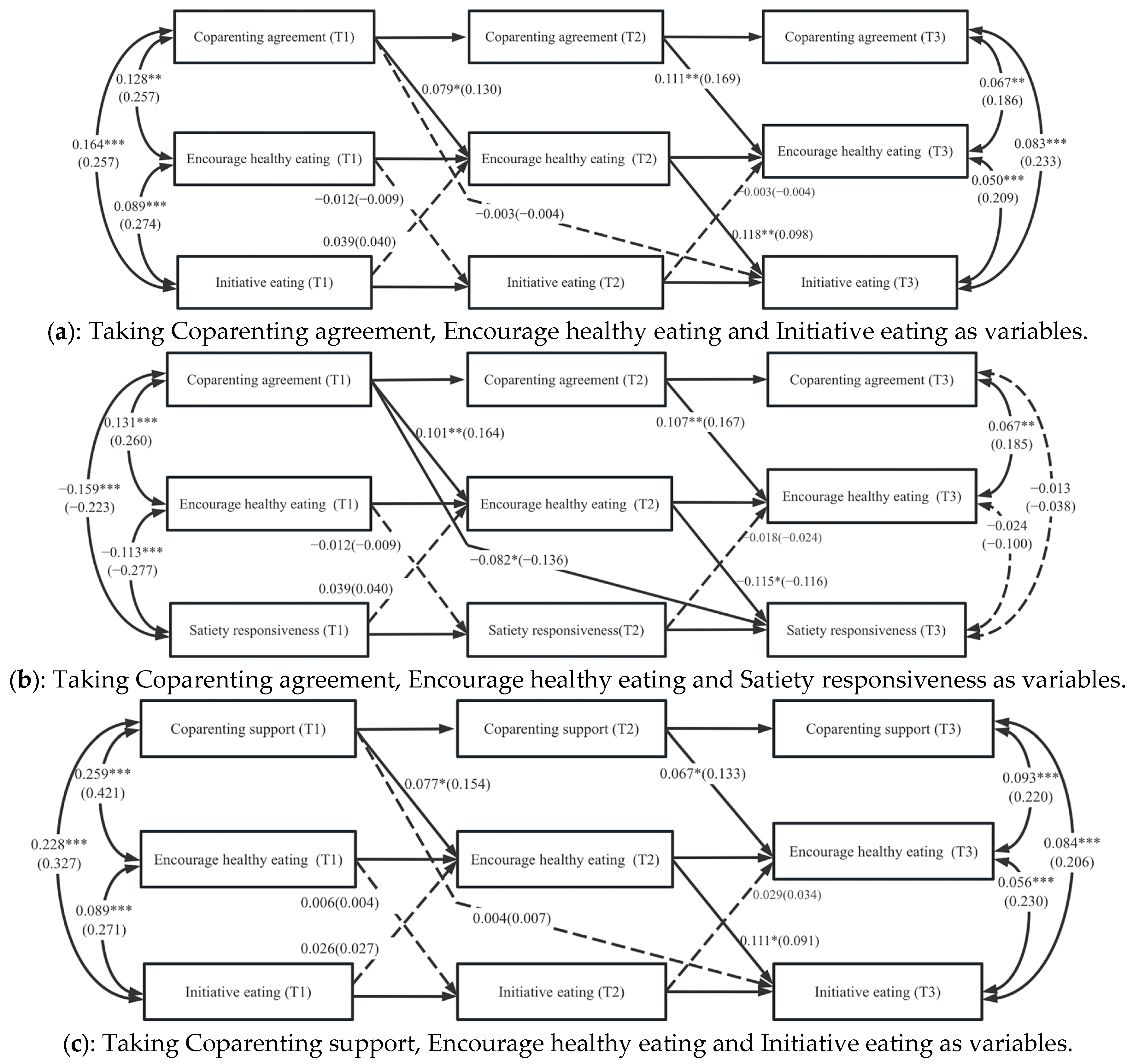

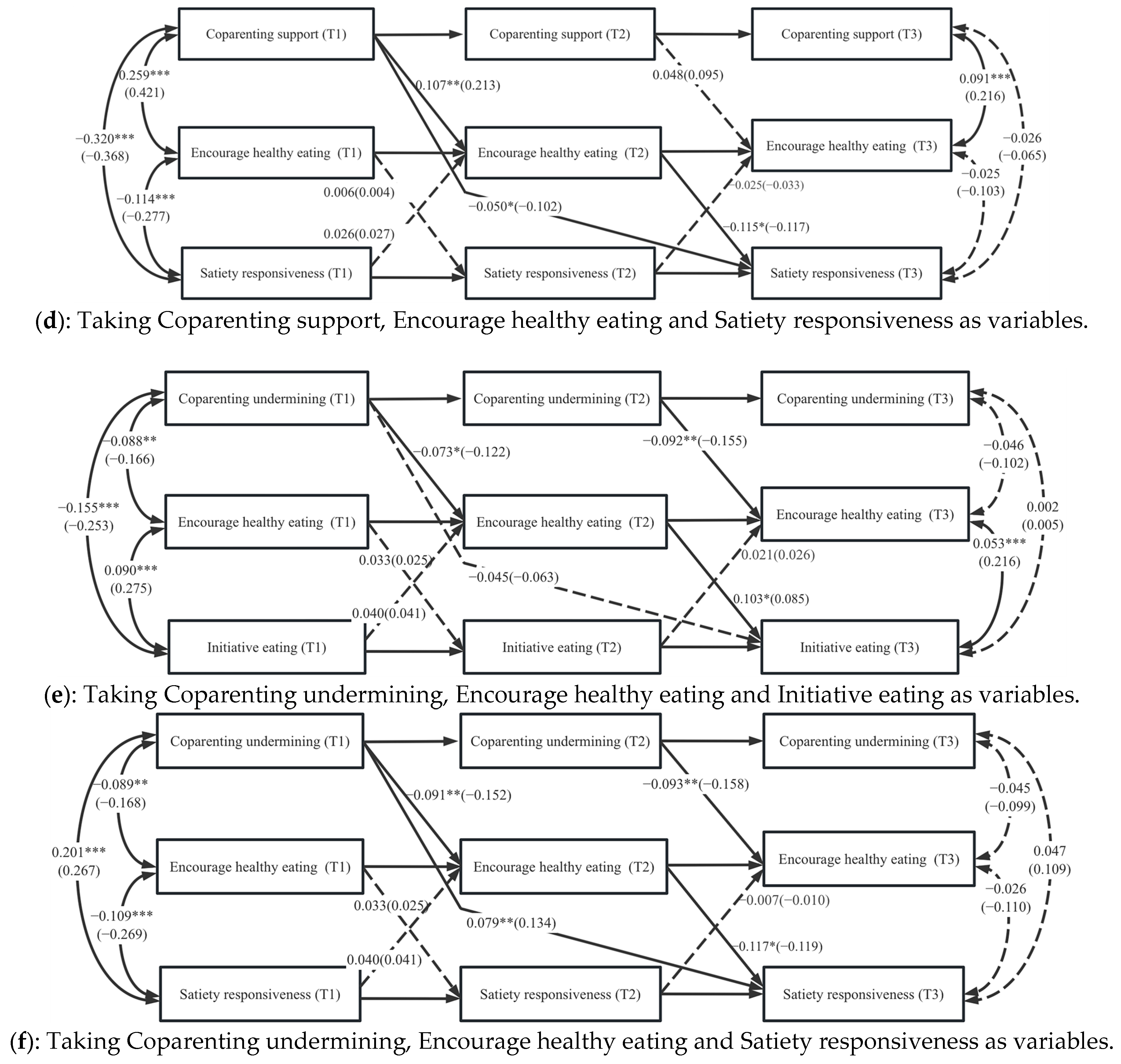

3.3. The Effects of Parent–Grandparent Coparenting Relationships on Preschool Children’s Eating Behaviors

4. Discussion

4.1. Coparenting Relationships and Child Eating Behaviors

4.2. Bidirectional Feeding–Eating Dynamics

4.3. Methodological Considerations

5. Strengths, Limitations, and Future Directions

6. Practical Implications

7. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sudo, M.; Low, P.H.X.; Kyeong, Y.; Meaney, M.J.; Kee, M.Z.L.; Chen, H.; Broekman, B.F.P.; Nadarajan, R.; Rifkin-Graboi, A.; Tiemeier, H.; et al. Grandparents’ and domestic helpers’ childcare support: Implications for well-being in Asian families. J. Marriage Fam. 2024, 87, 134–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulgaron, E.R.; Marchante, A.N.; Agosto, Y.; Lebron, C.N.; Delamater, A.M. Grandparent involvement and children’s health outcomes: The current state of the literature. Fam. Syst. Health 2016, 34, 260–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Settles, B.H.; Zhao, J.; Mancini, K.D.; Rich, A.; Pierre, S.; Oduor, A. Grandparents Caring for their Grandchildren: Emerging Roles and Exchanges in Global Perspectives. J. Comp. Fam. Stud. 2009, 40, 827–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bureau, U.S.C. Kinship Care in the United States. Available online: https://datacenter.aecf.org/data/tables/10455-children-in-kinship-care#detailed/1/any/false/2638,2554,2479,2097,1985,1757/any/20160,20161 (accessed on 20 January 2025).

- Li, X.; Liu, Y. Parent-Grandparent Coparenting Relationship, Maternal Parenting Self-efficacy, and Young Children’s Social Competence in Chinese Urban Families. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2019, 28, 1145–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayslip, B., Jr.; Kaminski, P.L. Grandparents raising their grandchildren: A review of the literature and suggestions for practice. Gerontologist 2005, 45, 262–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayslip, B.; Fruhauf, C.A.; Dolbin-MacNab, M.L. Grandparents Raising Grandchildren: What Have We Learned Over the Past Decade? Gerontologist 2019, 59, e152–e163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danielsbacka, M.; Křenková, L.; Tanskanen, A.O. Grandparenting, health, and well-being: A systematic literature review. Eur. J. Ageing 2022, 19, 341–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, X.; Chen, M.; He, R.; Xu, T. Toward an integrative framework of intergenerational coparenting within family systems: A scoping review. J. Fam. Theory Rev. 2023, 15, 78–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jongenelis, M.I.; Budden, T. The Influence of Grandparents on Children’s Dietary Health: A Narrative Review. Curr. Nutr. Rep. 2023, 12, 395–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeyrek, İ.; Güney, E.; Özaslan, A.; Dikmen, A.U. Eating Behavior in Children Aged 3-6: Relationship with the Child’s Temperament Characteristics and Parent’s Feeding Style. Brain Behav. 2025, 15, e70758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ducharme-Smith, K.; Brady, T.M.; Vizthum, D.; Caulfield, L.E.; Mueller, N.T.; Rosenstock, S.; Garcia-Larsen, V. Diet quality scores associated with improved cardiometabolic measures among African American adolescents. Pediatr. Res. 2022, 92, 853–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Federation, W.O. World Obesity Atlas 2024; World Obesity Federation: London, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- National Health Commission of the People’s Republic of China. The Nutrition and Chronic Diseases of Chinese Residents Report (2020); National Health Commission of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2020. Available online: http://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2020-12/24/content_5572983.htm (accessed on 10 January 2025).

- Waxman, A. WHO global strategy on diet, physical activity and health. Food Nutr. Bull. 2004, 25, 292–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, J.; Jiang, X.; Zhu, T.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Yang, X.; Shang, L. Caregivers’ feeding behaviour, children’s eating behaviour and weight status among children of preschool age in China. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 2021, 34, 807–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Zhu, B.; Wu, R.; Chang, Y.S.; Cao, Y.; Zhu, D. Bidirectional Associations between Parental Non-Responsive Feeding Practices and Child Eating Behaviors: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Longitudinal Prospective Studies. Nutrients 2022, 14, 1896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, J.; Zhang, Y.; Lu, Z.; Xu, T.; Zhang, H.; Tan, Z.; Yu, L.; Jiang, X.; Shang, L. Correlation between Children’s eating behaviors and caregivers’ feeding behaviors among preschool children in China. Appetite 2019, 138, 146–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Black, M.M.; Hurley, K.M. Infant Nutrition. In The Wiley-Blackwell Handbook of Infant Development; John and Wiley and Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2010; pp. 33–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansen, P.W.; Derks, I.P.M.; Mou, Y.; van Rijen, E.H.M.; Gaillard, R.; Micali, N.; Voortman, T.; Hillegers, M.H.J. Associations of parents’ use of food as reward with children’s eating behaviour and BMI in a population-based cohort. Pediatr. Obes. 2020, 15, e12662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniels, L.A. Feeding Practices and Parenting: A Pathway to Child Health and Family Happiness. Ann. Nutr. Metab. 2019, 74 (Suppl. S2), 29–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitchurch, G.G.; Constantine, L.L. Systems Theory. In Sourcebook of Family Theories and Methods: A Contextual Approach; Boss, P., Doherty, W.J., LaRossa, R., Schumm, W.R., Steinmetz, S.K., Eds.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 1993; pp. 325–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feinberg, M.E. The Internal Structure and Ecological Context of Coparenting: A Framework for Research and Intervention. Parent. Sci. Pract. 2003, 3, 95–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minuchin, P. Relationships Within the Family: A Systems Perspective on Development. In Relationships Within Families; Clarendon Press: Oxford, UK, 1988; pp. 7–26. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, H.A.; Jansen, E.; Rossi, T. ‘It’s not worth the fight’: Fathers’ perceptions of family mealtime interactions, feeding practices and child eating behaviours. Appetite 2020, 150, 104642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, C.C.; Domoff, S.E.; Pesch, M.H.; Lumeng, J.C.; Miller, A.L. Coparenting in the feeding context: Perspectives of fathers and mothers of preschoolers. Eat. Weight Disord. 2020, 25, 1061–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoang, N.-P.T.; Haslam, D.; Sanders, M. Coparenting Conflict and Cooperation between Parents and Grandparents in Vietnamese Families: The Role of Grandparent Psychological Control and Parent–Grandparent Communication. Fam. Process 2020, 59, 1161–1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keller, K.L.; Pietrobelli, A.; Johnson, S.L.; Faith, M.S. Maternal restriction of children’s eating and encouragements to eat as the ‘non-shared environment’: A pilot study using the child feeding questionnaire. Int. J. Obes. 2006, 30, 1670–1675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.; Lu, F.C.; Department of Disease Control Ministry of Health, PR China. The guidelines for prevention and control of overweight and obesity in Chinese adults. Biomed. Environ. Sci. 2004, 17, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- WS/T 424-2013; Anthropometric Measurements Method in Health Surveillance. Standards Press of China: Beijing, China, 2013.

- WHO Multicentre Growth Reference Study Group; de Onis, M. WHO Child Growth Standards based on length/height, weight and age. Acta. Paediatr. Suppl. 2006, 95, 76–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiaowei, L.; Xiaoyu, W. Revision of the Grandparents-Parents Co-parenting Relationships Scale in Chinese families. Chin. J. Clin. Psychol. 2018, 26, 882–886. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Qian, Y.M.; Li, H.Y.; Wang, S.; Chen, B.B. A Study on the “Red Face and White Face” under the Three-Dimensional Construct of Coparenting in Chinese Families. J. Soochow Univ. (Educ. Sci. Ed.) 2018, 1, 100–111. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, J.; Zhang, H.; Xu, T.; Yang, X.-J.; Yu, L.-L.; Jiang, X.; Shang, L. Development and evaluation of Preschooler′ s Parents Feeding Behavior Scale. Chin. J. Child Health Care 2018, 26, 483–487. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Yang, X.; Jiang, X.; Yuan, J.; Xu, T.; Shang, L. Revaluation of Preschool Children Eating Behavior Questionnaire based on multidimensional item response theory. Chin. J. Child Health Care 2019, 27, 236–240. [Google Scholar]

- Young, J.Q.; John, M.; Thakker, K.; Friedman, K.; Sugarman, R.; Sewell, J.L.; O’Sullivan, P.S. Evidence for validity for the Cognitive Load Inventory for Handoffs. Med. Educ. 2021, 55, 222–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentler, P.M. Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psychol. Bull. 1990, 107, 238–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Huang, F.; Zhang, L.; Li, S.; Zhang, J. The effect of high blood pressure-health literacy, self-management behavior, self-efficacy and social support on the health-related quality of life of Kazakh hypertension patients in a low-income rural area of China: A structural equation model. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett, M.A.; Mills-Koonce, W.R.; Gustafsson, H.; Cox, M.; Family Life Project Key Investigators. Mother-Grandmother Conflict, Negative Parenting, and Young Children’s Social Development in Multigenerational Families. Fam. Relat. 2012, 61, 864–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, C.; Baylin, A.; Haines, J.; Miller, A.L.; Bauer, K.W. Associations Between Coparenting Quality, the Home Food Environment, and Child’s Body Mass Index. Child. Obes. 2025, 21, 319–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Douglas, S.; Darlington, G.; Beaton, J.; Davison, K.; Haines, J.; on behalf of the Guelph Family Health Study. Associations between Coparenting Quality and Food Parenting Practices among Mothers and Fathers in the Guelph Family Health Study. Nutrients 2021, 13, 750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhou, S.; Guo, Y. Bidirectional Longitudinal Relations Between Parent-Grandparent Co-parenting Relationships and Chinese Children’s Effortful Control During Early Childhood. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jongenelis, M.I.; Morley, B.; Pratt, I.S.; Talati, Z. Diet quality in children: A function of grandparents’ feeding practices? Food Qual. Prefer. 2020, 83, 103899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathews, R.; Nadorff, D. Too Many Treats or Not Enough to Eat? The Impact of Caregiving Grandparents on Child Food Security and Nutrition. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 5796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrow, C. A comparison between the feeding practices of parents and grandparents. Eat Behav. 2014, 15, 339–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Adab, P.; Cheng, K.K. The role of grandparents in childhood obesity in China—Evidence from a mixed methods study. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2015, 12, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodgers, R.F.; Paxton, S.J.; Massey, R.; Campbell, K.J.; Wertheim, E.H.; Skouteris, H.; Gibbons, K. Maternal feeding practices predict weight gain and obesogenic eating behaviors in young children: A prospective study. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2013, 10, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerner, R.M.; Lerner, J.V. Developmental Psychology. In Encyclopedia of Sciences and Religions; Runehov, A.L.C., Oviedo, L., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2013; pp. 624–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lidgate, E.D.; Li, B.; Lindenmeyer, A. A qualitative insight into informal childcare and childhood obesity in children aged 0-5 years in the UK. BMC Public Health 2018, 18, 1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jansen, E.; Williams, K.E.; Mallan, K.M.; Nicholson, J.M.; Daniels, L.A. Bidirectional associations between mothers’ feeding practices and child eating behaviours. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2018, 15, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grolnick, W.S.; Pomerantz, E.M. Issues and Challenges in Studying Parental Control: Toward a New Conceptualization. Child Dev. Perspect. 2009, 3, 165–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eneli, I.U.; Crum, P.A.; Tylka, T.L. The trust model: A different feeding paradigm for managing childhood obesity. Obesity 2008, 16, 2197–2204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finnane, J.M.; Jansen, E.; Mallan, K.M.; Daniels, L.A. Mealtime Structure and Responsive Feeding Practices Are Associated with Less Food Fussiness and More Food Enjoyment in Children. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2017, 49, 11–18.e11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansen, E.; Mallan, K.M.; Nicholson, J.M.; Daniels, L.A. The feeding practices and structure questionnaire: Construction and initial validation in a sample of Australian first-time mothers and their 2-year olds. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2014, 11, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrow, C.V.; Galloway, A.T.; Fraser, K. Sibling eating behaviours and differential child feeding practices reported by parents. Appetite 2009, 52, 307–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuiper, R.M.; and Ryan, O. Drawing Conclusions from Cross-Lagged Relationships: Re-Considering the Role of the Time-Interval. Struct. Equ. Model. A Multidiscip. J. 2018, 25, 809–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lilly, C.L. The Chicken or the Egg: One Statistical Approach for Determining the Direction of Influence. J. Pediatr. 2020, 227, 328–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | T1 [mean (S.D.)] | T2 [mean (S.D.)] | T3 [mean (S.D.)] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Parent–grandparent coparenting relationships | |||

| Coparenting support | 3.95 (1.05) | 3.99 (1.06) | 3.89 (1.01) |

| Coparenting agreement | 3.38 (0.68) | 3.40 (0.64) | 3.35 (0.61) |

| Coparenting undermining | 1.95 (1.01) | 2.04 (1.03) | 2.15 (1.11) |

| Good cop-bad cop | 1.76 (1.11) | 1.84 (1.15) | 1.86 (1.20) |

| Caregivers’ feeding behaviors | |||

| Supervised feeding | 4.11 (0.72) | 4.07 (0.71) | 4.02 (0.79) |

| Behavior-restricted feeding | 4.11 (0.55) | 4.17 (0.56) | 4.13 (0.59) |

| Encourage healthy eating | 4.08 (0.44) | 4.05 (0.53) | 4.05 (0.50) |

| Content-restricted feeding | 3.51 (0.71) | 3.65 (0.69) | 3.57 (0.69) |

| Regard food as rewards | 3.34 (0.73) | 3.41 (0.76) | 3.17 (0.77) |

| Forced feeding | 3.23 (0.76) | 3.11 (0.78) | 2.86 (0.78) |

| Preschool children’s eating behaviors | |||

| Initiative eating | 3.38 (0.53) | 3.52 (0.62) | 3.64 (0.59) |

| Food fussiness | 3.04 (0.60) | 2.88 (0.69) | 2.82 (0.61) |

| Exogenous eating | 2.98 (0.56) | 2.88 (0.54) | 2.83 (0.52) |

| Satiety responsiveness | 2.67 (0.59) | 2.67 (0.65) | 2.64 (0.60) |

| Unhealthy eating habits | 2.60 (0.74) | 2.40 (0.78) | 2.28 (0.69) |

| Food responsiveness | 2.49 (0.54) | 2.44 (0.56) | 2.40 (0.52) |

| Emotional eating | 2.06 (0.54) | 1.89 (0.51) | 1.86 (0.53) |

| Parent–Grandparent Coparenting Relationships | Feeding Behaviors | Eating Behaviors | Figure | χ2 | df | CFI | TLI | RMSEA | SRMR | AIC | BIC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coparenting agreement | Encourage healthy eating | Initiative eating | Figure 4a | 304.163 | 135 | 0.870 | 0.818 | 0.068 | 0.087 | 4649.112 | 4908.730 |

| Satiety responsiveness | Figure 4b | 145.984 | 95 | 0.950 | 0.925 | 0.044 | 0.070 | 4834.819 | 5076.408 | ||

| Coparenting support | Encourage healthy eating | Initiative eating | Figure 4c | 299.712 | 141 | 0.884 | 0.837 | 0.064 | 0.091 | 4912.253 | 5182.688 |

| Satiety responsiveness | Figure 4d | 184.558 | 100 | 0.929 | 0.891 | 0.056 | 0.081 | 5057.353 | 5313.365 | ||

| Coparenting undermining | Encourage healthy eating | Initiative eating | Figure 4e | 243.070 | 138 | 0.902 | 0.866 | 0.053 | 0.073 | 4913.379 | 5162.179 |

| Satiety responsiveness | Figure 4f | 172.557 | 118 | 0.941 | 0.914 | 0.041 | 0.065 | 5056.176 | 5312.187 |

| Model Pathway | Type of Effect | Estimated (β) | SE | Boot 95%CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coparenting agreement T1 → Encourage healthy eating T2 → Initiative eating T3 Figure 4a | Total effect | 0.006 | 0.034 | [−0.050, 0.062] |

| Indirect effect | 0.009 | 0.006 | [0.000, 0.019] | |

| Direct effect | −0.003 | 0.034 | [−0.060, 0.053] | |

| The proportion of indirect effect | 33.3% | |||

| Coparenting agreement T1 → Encourage healthy eating T2 → Satiety responsiveness T3 Figure 4b | Total effect | −0.094 | 0.032 | [−0.146, −0.041] |

| Indirect effect | −0.012 | 0.006 | [−0.022, −0.001] | |

| Direct | −0.082 | 0.033 | [−0.136, −0.028] | |

| The proportion of indirect effect | 12.8% | |||

| Coparenting support T1 → Encourage healthy eating T2 → Initiative eating T3 Figure 4c | Total effect | 0.013 | 0.027 | [−0.032, 0.058] |

| Indirect effect | 0.009 | 0.005 | [0.000, 0.017] | |

| Direct | 0.004 | 0.028 | [−0.042, 0.050] | |

| The proportion of indirect effect | 69.20% | |||

| Coparenting support T1 → Encourage healthy eating T2 → Satiety responsiveness T3 Figure 4d | Total effect | −0.062 | 0.027 | [−0.107, −0.018] |

| Indirect effect | −0.012 | 0.006 | [−0.023, −0.002] | |

| Direct | −0.050 | 0.028 | [−0.097, −0.003] | |

| The proportion of indirect effect | 19.40% | |||

| Coparenting undermining T1 → Encourage healthy eating T2 → Initiative eating T3 Figure 4e | Total effect | −0.053 | 0.029 | [−0.101, −0.005] |

| Indirect effect | −0.007 | 0.005 | [−0.016, 0.001] | |

| Direct | −0.045 | 0.030 | [−0.094, 0.003] | |

| The proportion of indirect effect | 13.2% | |||

| Coparenting undermining T1 → Encourage healthy eating T2 → Satiety responsiveness T3 Figure 4f | Total effect | 0.090 | 0.030 | [0.040, 0.139] |

| Indirect effect | 0.011 | 0.006 | [0.001, 0.020] | |

| Direct effect | 0.079 | 0.030 | [0.029, 0.129] | |

| The proportion of indirect effect | 12.2% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhao, Z.; Qu, F.; Wu, R.; Wei, X.; Song, X.; Wu, C.; Wang, J.; Hua, W.; Zhu, D. The Longitudinal Influence of Parent–Grandparent Coparenting Relationships on Preschoolers’ Eating Behaviors in Chinese Urban Families: The Mediating Roles of Caregivers’ Feeding Behaviors. Nutrients 2025, 17, 2961. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17182961

Zhao Z, Qu F, Wu R, Wei X, Song X, Wu C, Wang J, Hua W, Zhu D. The Longitudinal Influence of Parent–Grandparent Coparenting Relationships on Preschoolers’ Eating Behaviors in Chinese Urban Families: The Mediating Roles of Caregivers’ Feeding Behaviors. Nutrients. 2025; 17(18):2961. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17182961

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhao, Zhihui, Fangge Qu, Ruxing Wu, Xiaoxue Wei, Xinyi Song, Chenjun Wu, Jian Wang, Wenzhe Hua, and Daqiao Zhu. 2025. "The Longitudinal Influence of Parent–Grandparent Coparenting Relationships on Preschoolers’ Eating Behaviors in Chinese Urban Families: The Mediating Roles of Caregivers’ Feeding Behaviors" Nutrients 17, no. 18: 2961. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17182961

APA StyleZhao, Z., Qu, F., Wu, R., Wei, X., Song, X., Wu, C., Wang, J., Hua, W., & Zhu, D. (2025). The Longitudinal Influence of Parent–Grandparent Coparenting Relationships on Preschoolers’ Eating Behaviors in Chinese Urban Families: The Mediating Roles of Caregivers’ Feeding Behaviors. Nutrients, 17(18), 2961. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17182961