Socio-Demographic Disparities in Diet and Their Association with Physical and Mental Well-Being: Million-Participant Cross-Sectional Study in Poland

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Population

2.2. Survey and Data Collection, and Ethical Consideration

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Participant Characteristics

3.2. Assessment of Eating Habits

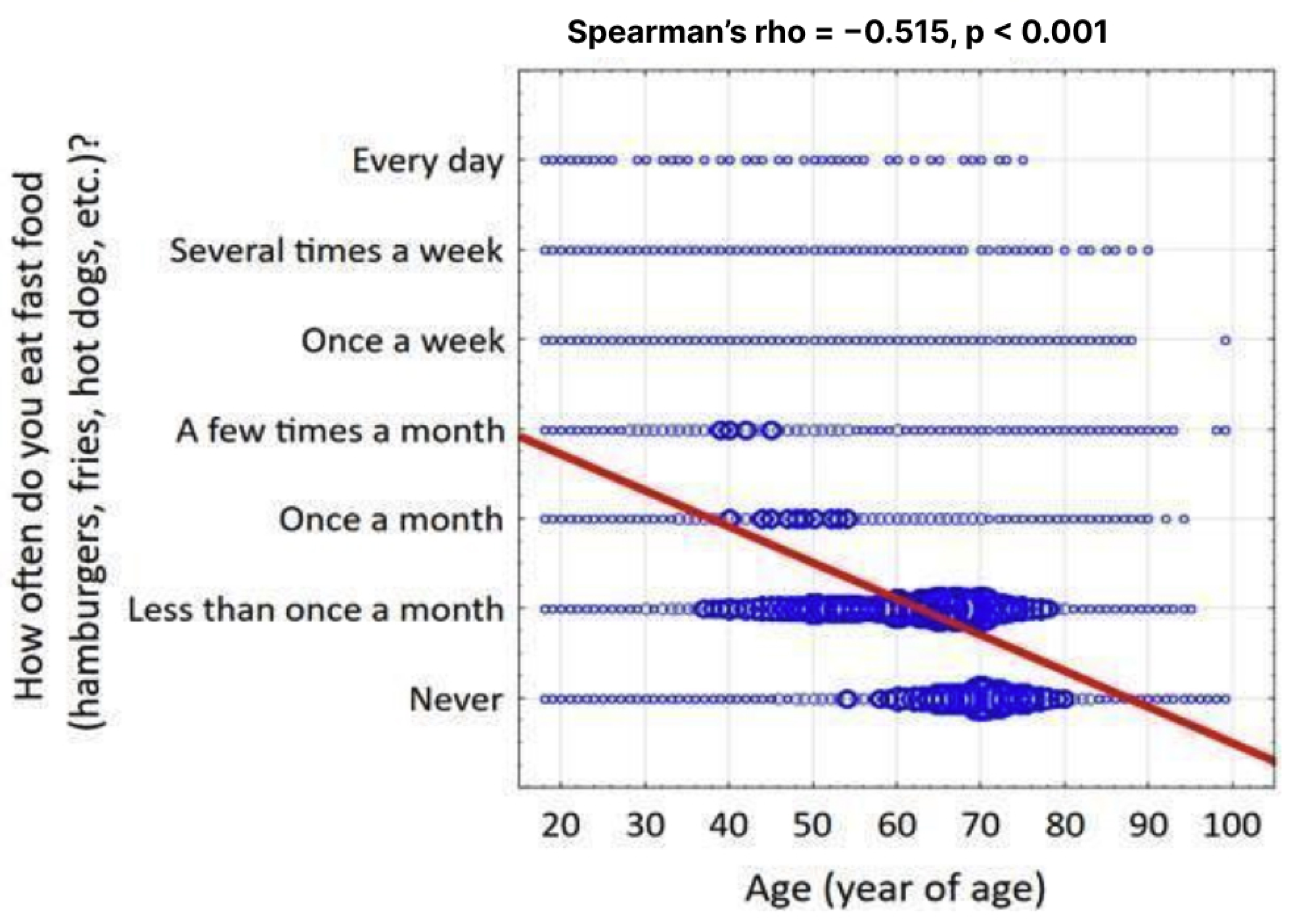

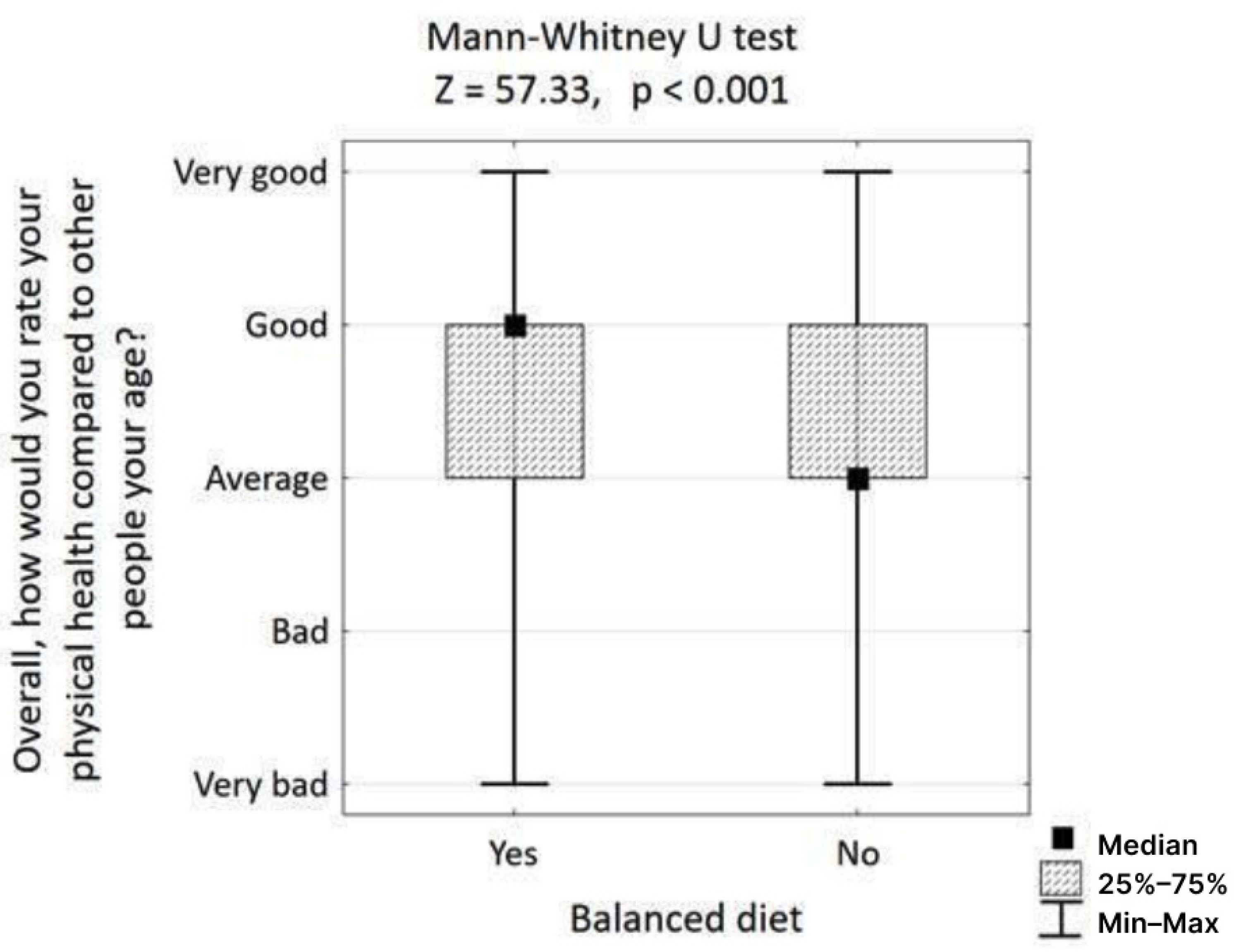

3.3. Association of Dietary Habits with Self-Rated Health

3.4. Associations with Socio-Demographic, Psychosocial, and Educational Factors

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Locke, A.; Schneiderhan, J.; Zick, S.M. Diets for Health: Goals and Guidelines. Am. Fam. Physician 2018, 97, 721–728. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cena, H.; Calder, P.C. Defining a Healthy Diet: Evidence for The Role of Contemporary Dietary Patterns in Health and Disease. Nutrients 2020, 12, 334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Healthy Diet. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/healthy-diet (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- Enriquez, J.P.; Archila-Godinez, J.C. Social and cultural influences on food choices: A review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2022, 62, 3698–3704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gumŕ, J.; Solé-Auró, A.; Arpino, B. Examining social determinants of health: The role of education, household arrangements and country groups by gender. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leblanc, V.; Bégin, C.; Corneau, L.; Dodin, S.; Lemieux, S. Gender differences in dietary intakes: What is the contribution of motivational variables? J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 2015, 28, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pryde, M.M.; Kannel, W.B. Efficacy of dietary behavior modification for preserving cardiovascular health and longevity. Cardiol. Res. Pract. 2010, 2011, 820457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Oza, M.J.; Laddha, A.P.; Gaikwad, A.B.; Mulay, S.R.; Kulkarni, Y.A. Role of dietary modifications in the management of type 2 diabetic complications. Pharmacol. Res. 2021, 168, 105602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, L.J.; Barnes, K.A.; Ball, L.E.; Mitchell, L.J.; Sladdin, I.; Lee, P.; Williams, L.T. Effectiveness of dietetic consultation for lowering blood lipid levels in the management of cardiovascular disease risk: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Nutr. Diet. 2019, 76, 199–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ball, L.E.; Sladdin, I.K.; Mitchell, L.J.; Barnes, K.A.; Ross, L.J.; Williams, L.T. Quality of development and reporting of dietetic intervention studies in primary care: A systematic review of randomised controlled trials. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 2018, 31, 47–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desroches, S.; Lapointe, A.; Ratté, S.; Gravel, K.; Légaré, F.; Turcotte, S. Interventions to enhance adherence to dietary advice for preventing and managing chronic diseases in adults. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2013, 2, CD008722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misiak, B.; Piotrowski, P.; Beszłej, J.A.; Kalinowska, S.; Chęć, M.; Samochowiec, J. Metabolic Dysregulation and Psychosocial Stress in Patients with Schizophrenia Spectrum Disorders: A Case-Control Study. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 3822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalinowska, S.; Trześniowska-Drukała, B.; Kłoda, K.; Safranow, K.; Misiak, B.; Cyran, A.; Samochowiec, J. The Association between Lifestyle Choices and Schizophrenia Symptoms. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoś, K.; Rychlik, E.; Woźniak, A.; Ołtarzewski, M.; Jankowski, M.; Gujski, M.; Juszczyk, G. Prevalence and Sociodemographic Factors Associated with Overweight and Obesity among Adults in Poland: A 2019/2020 Nationwide Cross-Sectional Survey. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Overweight and Obesity—BMI Statistics. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Overweight_and_obesity_-_BMI_statistics (accessed on 22 June 2025).

- Żarnowski, A.; Jankowski, M.; Gujski, M. Public Awareness of Diet-Related Diseases and Dietary Risk Factors: A 2022 Nationwide Cross-Sectional Survey among Adults in Poland. Nutrients 2022, 14, 3285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Żarnowski, A.; Jankowski, M.; Gujski, M. Use of Mobile Apps and Wearables to Monitor Diet, Weight, and Physical Activity: A Cross-Sectional Survey of Adults in Poland. Med. Sci. Monit. 2022, 28, e937948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forberger, S.; Reisch, L.; Meshkovska, B.; Lobczowska, K.; Scheller, D.A.; Wendt, J.; Christianson, L.; Frense, J.; Steinacker, J.M.; Luszczynska, A.; et al. Sugar-sweetened beverage tax implementation processes: Results of a scoping review. Health Res. Policy Syst. 2022, 20, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forberger, S.; Reisch, L.A.; Meshkovska, B.; Lobczowska, K.; Scheller, D.A.; Wendt, J.; Christianson, L.; Frense, J.; Steinacker, J.M.; Woods, C.B.; et al. What we know about the actual implementation process of public physical activity policies: Results from a scoping review. Eur. J. Public Health 2022, 32 (Suppl. S4), iv59–iv65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Żarnowski, A.; Jankowski, M.; Gujski, M. Nutrition Knowledge, Dietary Habits, and Food Labels Use-A Representative Cross-Sectional Survey among Adults in Poland. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 11364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitchell, L.J.; Ball, L.E.; Ross, L.J.; Barnes, K.A.; Williams, L.T. Effectiveness of Dietetic Consultations in Primary Health Care: A Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Trials. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2017, 117, 1941–1962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szetela, P.P. Coordinated care in primary health care in Poland in 2021–2024: First experiences. Med. Og. Nauk. Zdr. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamiński, M.; Skonieczna-Żydecka, K.; Nowak, J.K.; Stachowska, E. Global and local diet popularity rankings, their secular trends, and seasonal variation in Google Trends data. Nutrition 2020, 79–80, 110759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Lee, Y.; Micha, R.; Li, Y.; Mozaffarian, D. Trends in junk food consumption among US children and adults, 2001–2018. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2021, 114, 1039–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lüscher, T.F. Nutrition, obesity, diabetes, and cardiovascular outcomes: A deadly association. Eur. Heart J. 2020, 41, 2603–2607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Share of Daily Internet Users in Poland According to Age from 2014 to 2020. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1241858/poland-internet-users-use-accessed-internet-daily-age/ (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- Heidemann, C.; Scheidt-Nave, C.; Richter, A.; Mensink, G.B. Dietary patterns are associated with cardiometabolic risk factors in a representative study population of German adults. Br. J. Nutr. 2011, 106, 1253–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaufman-Shriqui, V.; Sherf-Dagan, S.; Boaz, M.; Birk, R. Virtual nutrition consultation: What can we learn from the COVID-19 pandemic? Public Health Nutr. 2021, 24, 1166–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidor, A.; Rzymski, P. Dietary Choices and Habits during COVID-19 Lockdown: Experience from Poland. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paszynska, E.; Cofta, S.; Hernik, A.; Otulakowska-Skrzynska, J.; Springer, D.; Roszak, M.; Sidor, A.; Rzymski, P. Self-Reported Dietary Choices and Oral Health Care Needs during COVID-19 Quarantine: A Cross-Sectional Study. Nutrients 2022, 14, 313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, L.M.; Cassady, D.L.; Beckett, L.A.; Applegate, E.A.; Wilson, M.D.; Gibson, T.N.; Ellwood, K. Misunderstanding of Front-Of-Package Nutrition Information on US Food Products. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0125306, Erratum in PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0134772. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0134772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, L.M.; Cassady, D.L. The effects of nutrition knowledge on food label use. A review of the literature. Appetite 2015, 92, 207–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, V.S.; Popkin, B.M.; Bray, G.A.; Després, J.P.; Hu, F.B. Sugar-sweetened beverages, obesity, type 2 diabetes mellitus, and cardiovascular disease risk. Circulation 2010, 121, 1356–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malik, V.S.; Popkin, B.M.; Bray, G.A.; Després, J.P.; Willett, W.C.; Hu, F.B. Sugar-sweetened beverages and risk of metabolic syndrome and type 2 diabetes: A meta-analysis. Diabetes Care 2010, 33, 2477–2483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, C.A.; Cannon, G.; Moubarac, J.C.; Levy, R.B.; Louzada, M.L.C.; Jaime, P.C. The UN Decade of Nutrition, the NOVA food classification and the trouble with ultra-processing. Public Health Nutr. 2018, 21, 5–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raport “Sytuacja Zdrowotna Ludności Polski i jej Uwarunkowania—2025”. Available online: https://www.pzh.gov.pl/raport-sytuacja-zdrowotna-ludnosci-polski-i-jej-uwarunkowania-2025/ (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- O’Neil, A.; Itsiopoulos, C.; Skouteris, H.; Opie, R.S.; McPhie, S.; Hill, B.; Jacka, F.N. Preventing mental health problems in offspring by targeting dietary intake of pregnant women. BMC Med. 2014, 12, 208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opie, R.S.; O’Neil, A.; Itsiopoulos, C.; Jacka, F.N. The impact of whole-of-diet interventions on depression and anxiety: A systematic review of randomised controlled trials. Public Health Nutr. 2015, 18, 2074–2093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacka, F.N.; O’Neil, A.; Opie, R.; Itsiopoulos, C.; Cotton, S.; Mohebbi, M.; Castle, D.; Dash, S.; Mihalopoulos, C.; Chatterton, M.L.; et al. A randomised controlled trial of dietary improvement for adults with major depression (the ‘SMILES’ trial). BMC Med. 2017, 15, 23, Erratum in BMC Med. 2018, 16, 236. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-018-1220-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Witaszek, T.; Kłoda, K.; Mastalerz-Migas, A.; Babicki, M. Association between Symptoms of Depression and Generalised Anxiety Disorder Evaluated through PHQ-9 and GAD-7 and Anti-Obesity Treatment in Polish Adult Women. Nutrients 2024, 16, 2438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aune, D.; Giovannucci, E.; Boffetta, P.; Fadnes, L.T.; Keum, N.; Norat, T.; Greenwood, D.C.; Riboli, E.; Vatten, L.J.; Tonstad, S. Fruit and vegetable intake and the risk of cardiovascular disease, total cancer and all-cause mortality-a systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of prospective studies. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2017, 46, 1029–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bertoia, M.L.; Mukamal, K.J.; Cahill, L.E.; Hou, T.; Ludwig, D.S.; Mozaffarian, D.; Willett, W.C.; Hu, F.B.; Rimm, E.B. Changes in Intake of Fruits and Vegetables and Weight Change in United States Men and Women Followed for Up to 24 Years: Analysis from Three Prospective Cohort Studies. PLoS Med. 2015, 12, e1001878, Erratum in PLoS Med. 2016, 13, e1001956. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1001956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Total N (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | Women | 619,294 (51.77%) |

| Men | 576,808 (48.23%) | |

| Age (years) M ± SD | 44.7 ± 15.3 | |

| Age | 18–24 | 114,128 (9.5%) |

| 25–34 | 236,976 (19.8%) | |

| 35–44 | 293,433 (24.5%) | |

| 45–54 | 229,648 (19.2%) | |

| 55+ | 321,918 (26.9%) | |

| Place of residence | Village | 413,166 (34.5%) |

| Up to 19 k inhab. | 142,540 (11.9%) | |

| 20–49 k inhab. | 153,755 (12.9%) | |

| 50–99 k inhab. | 119,493 (10.0%) | |

| 100–199 k inhab. | 113,578 (9.5%) | |

| 200–499 k inhab. | 104,995 (8.8%) | |

| 500+ k inhab. | 148,574 (12.4%) | |

| Education level | Basic | 309,560 (25.9%) |

| Secondary | 441,549 (36.9%) | |

| Higher | 444,992 (37.2%) | |

| Chronic diseases | Any chronic disease | |

| Arterial hypertension | 334,367 (28.0%) | |

| Diabetes mellitus | 92,451 (7.7%) | |

| Heart disease | 128,515 (10.7%) | |

| COPD | 27,423 (2.3%) | |

| Asthma/allergy | 245,995 (20.6%) | |

| Depression | 159,778 (13.4%) | |

| Cancer | 51,954 (4.3%) | |

| Joint disease | 213,222 (17.8%) | |

| Neurological disease | 127,767 (10.7%) | |

| BMI | >30 | 256,098 (21.4%) |

| 25–29.9 | 421,429 (39.2%) | |

| 18.5–24.9 | 481,839 (40.2%) | |

| <18.5 | 24,771 (2.00%) | |

| Variable | N (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Being on diet | Balanced | 254,976 (21.3%) |

| Vegetarian | 54,403 (4.5%) | |

| Vegan | 5709 (0.5%) | |

| Meat | 324,763 (27.2%) | |

| Gluten free | 9228 (0.8%) | |

| Dairy free | 8520 (0.7%) | |

| With carbohydrate restriction | 47,782 (4.0%) | |

| With less sodium | 72,095 (6.0%) | |

| Other type of meals | 28,334 (2.4%) | |

| I don’t know/it’s hard to say | 390,291 (32.6%) | |

| Eating fast food? | Every day | 2965 (0.2%) |

| Several times a week | 31,699 (2.7%) | |

| Once a week | 66,498 (5.6%) | |

| A few times a month | 224,699 (18.8%) | |

| Once a month | 203,510 (17.0%) | |

| Less than once a month | 482,696 (40.4%) | |

| I never eat such products | 184,035(15.4%) | |

| Drinking sweetened beverages | Every day | 139,778 (11.7%) |

| Several times a week | 154,317 (12.9%) | |

| Once a week | 80,241 (6.7%) | |

| A few times a month | 201,909 (16.9%) | |

| Once a month | 95,931 (8.0%) | |

| Less than once a month | 293,452 (24.5%) | |

| I never drink such products | 230,475 (19.3%) | |

| Energy drinks | 3 or more times a day | 4691 (0.4%) |

| 1 to 2 times a day | 13,059 (1.1%) | |

| Several times a week | 36,766 (3.1%) | |

| Once a week | 24,057 (2.0%) | |

| A few times a month | 62,056 (5.2%) | |

| Once a month | 47,126 (3.9%) | |

| Less than once a month | 201,997 (16.9%) | |

| I never drink such drinks | 806,349 (67.4%) | |

| Eating Vegetables | Every day | 381,998 (31.9%) |

| Several times a week | 509,451 (42.6%) | |

| Once a week | 109,104 (9.1%) | |

| A few times a month | 137,607 (11.5%) | |

| Once a month | 23,286 (1.9%) | |

| Less than once a month | 28,887 (2.4%) | |

| I never eat vegetables | 5769 (0.5%) | |

| Eating Fruits | Every day | 418,973 (35.0%) |

| Several times a week | 455,568 (38.1%) | |

| Once a week | 113,601 (9.5%) | |

| A few times a month | 136,884 (11.4%) | |

| Once a month | 28,473 (2.4%) | |

| Less than once a month | 35,160 (2.9%) | |

| I never eat fruit | 7444 (0.6%) | |

| Variable | Mental Health | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Very Good | Good | Average | Poor | Very Poor | p 1 | ||

| Fast food | Every day | 500 (16.8%) | 703 (23.7%) | 756 (25.5%) | 626 (21.1%) | 383 (12.9%) | <0.001 |

| Several times a week | 4242 (13.4%) | 9086 (28.7%) | 10,432 (32.9%) | 6276 (19.8%) | 1666 (5.3%) | ||

| Once a week | 10,177 (15.3%) | 23,932 (36.0%) | 20,782 (31.3%) | 9735 (14.6%) | 1874 (2.8%) | ||

| A few times a month | 38,210 (17.0%) | 84,269 (37.5%) | 68,346 (30.4%) | 28,874 (12.8%) | 5002 (2.2%) | ||

| Once a month | 40,158 (19.7%) | 83,433 (41.0%) | 56,130 (27.6%) | 20,578 (10.1%) | 3213 (1.6%) | ||

| Less than once a month | 111,235 (23.0%) | 205,849 (42.6%) | 121,007 (25.1%) | 38,801 (8.0%) | 5807 (1.2%) | ||

| Never | 53,885 (29.3%) | 79,391 (43.1%) | 38,496 (20.9%) | 10,647 (5.8%) | 1618 (0.9%) | ||

| Drinking beverages | Every day | 26,731 (19.1%) | 53,280 (38.1%) | 39,641 (28.4%) | 16,393 (11.7%) | 3735 (2.7%) | <0.001 |

| Several times a week | 28,029 (18.2%) | 60,264 (39.1%) | 43,971 (28.5%) | 18,494 (12.0%) | 3561 (2.3%) | ||

| Once a week | 15,339 (19.1%) | 32,527 (40.5%) | 22,555 (28.1%) | 8392 (10.5%) | 1431 (1.8%) | ||

| A few times a month | 39,167 (19.4%) | 82,014 (40.6%) | 56,428 (27.9%) | 21,027 (10.4%) | 3275 (1.6%) | ||

| Once a month | 19,156 (20.0%) | 39,568 (41.2%) | 26,416 (27.5%) | 9431 (9.8%) | 1363 (1.4%) | ||

| Less than once a month | 66,537 (22.7%) | 124,404 (42.4%) | 74,446 (25.4%) | 24,606 (8.4%) | 3461 (1.2%) | ||

| I never drink such drinks | 63,448 (27.5%) | 94,607 (41.0%) | 52,490 (22.8%) | 17,195 (7.5%) | 2737 (1.2%) | ||

| Energy drinks | Three or more times a day | 803 (17.1%) | 1082 (23.1%) | 1377 (29.3%) | 1025 (21.8%) | 407 (8.7%) | <0.001 |

| One to two times a day | 1912 (14.6%) | 3778 (28.9%) | 4144 (31.7) | 2414 (18.5%) | 813 (6.2%) | ||

| Several times a week | 6021 (16.4) | 11,572 (31.5) | 11,339 (30.8) | 6298 (17.1%) | 1538 (4.2%) | ||

| Once a week | 4399 (18.3%) | 8652 (36.0%) | 6974 (29.0%) | 3276 (13.6%) | 759 (3.2) | ||

| A few times a month | 10,829 (17.4%) | 22,672 (36.5%) | 18,166 (29.3%) | 8516 (13.7%) | 1875 (3.0%) | ||

| Once a month | 8409 (17.8%) | 18,329 (38.9%) | 13,466 (28.6%) | 5788 (12.3) | 1136 (2.4%) | ||

| Less than once a month | 40,673 (20.1%) | 81,701 (40.4%) | 55,128 (27.3%) | 21,088 (10.4%) | 3410 (1.7) | ||

| I never drink energy drinks | 185,361 (23.0%) | 338,879 (42.0%) | 205,352 (25.5%) | 67,133 (8.3%) | 9626 (1.2%) | ||

| Drinking alcohol | Two or more drinks a day | 5476 (17.0%) | 11,047 (34.3%) | 9750 (30.3%) | 4753 (14.8%) | 1143 (3.6%) | <0.001 |

| About one drink a day | 9291 (21.4%) | 17,676 (40.7%) | 11,637 (26.8%) | 4180 (9.6%) | 691 (1.6%) | ||

| Two or three drinks a week | 35,224 (21.9%) | 66,469 (41.2%) | 42,504 (26.4%) | 14,832 (9.2%) | 2140 (1.3%) | ||

| Two or three drinks a month | 39,030 (21.3%) | 75,255 (41.1%) | 48,506 (26.5%) | 17,476 (9.5%) | 2746 (1.5%) | ||

| One drink a month or less | 48,543 (20.6%) | 95,921 (40.6%) | 64,679 (27.4%) | 23,241 (9.8%) | 3780 (1.6%) | ||

| I never drink alcohol | 33,193 (20.2%) | 59,965 (36.6%) | 46,221 (28.2%) | 20,202 (12.3%) | 4441 (2.7%) | ||

| Vegetables | Every day | 104,985 (40.6%) | 154,086 (31.7%) | 87,439 (27.7%) | 30,626 (26.5%) | 4862 (24.9%) | <0.001 |

| Several times a week | 105,698 (40.9%) | 214,361 (44.0%) | 134,492 (42.6%) | 47,509 (41.1%) | 7391 (37.8%) | ||

| Once a week | 17,652 (6.8%) | 43,809 (9.0%) | 33,015 (10.4%) | 12,588 (10.9%) | 2039 (10.4%) | ||

| A few times a month | 21,588 (8.4%) | 54,521 (11.2%) | 42,095 (13.3%) | 16,328 (14.1%) | 3075 (15.7%) | ||

| Once a month | 3229 (1.2%) | 8540 (1.8%) | 7576 (2.4%) | 3291 (2.8%) | 652 (3.3%) | ||

| Less than once a month | 4149 (1.6%) | 9751 (2.0%) | 9625 (3.0%) | 4296 (3.7%) | 1067 (5.5%) | ||

| Never | 1103 (0.4%) | 1592 (0.3%) | 1703 (0.5%) | 898 (0.8%) | 473 (2.4%) | ||

| Fruit | Every day | 112,967 (43.7%) | 179,472 (36.9%) | 93,961 (29.7%) | 28,604 (24.8%) | 3969 (20.3%) | <0.001 |

| Several times a week | 93,923 (36.3%) | 190,099 (39.1%) | 122,009 (38.6%) | 42,830 (37.1%) | 6707 (34.3%) | ||

| Once a week | 18,812 (7.3%) | 43,410 (8.9%) | 34,420 (10.9%) | 14,400 (12.5%) | 2559 (13.1%) | ||

| A few times a month | 21,917 (8.5%) | 50,751 (10.4%) | 42,719 (13.5%) | 18,228 (15.8%) | 3270 (16.7%) | ||

| Once a month | 4163 (1.6%) | 9635 (2.0%) | 9388 (3.0%) | 4308 (3.7%) | 979 (5.0%) | ||

| Less than once a month | 5129 (2.0%) | 11,286 (2.3%) | 11,333 (3.6%) | 5852 (5.1%) | 1559 (8.0%) | ||

| Never | 1492 (0.6%) | 2009 (0.4%) | 2114 (0.7%) | 1312 (1.1%) | 516 (2.6%) | ||

| Red meat | Every day | 8913 (20.7%) | 16,326 (38.0%) | 12,215 (28.4%) | 4629 (10.8%) | 905 (2.1%) | <0.001 |

| One to three times a week | 66,108 (21.5%) | 127,695 (41.5%) | 81,893 (26.6%) | 27,701 (9.0%) | 4261 (1.4%) | ||

| Once or twice a month | 74,535 (21.1%) | 141,676 (40.2%) | 94,887 (26.9%) | 35,498 (10.1%) | 5952 (1.7%) | ||

| Never | 12,351 (17.0%) | 26,164 (36.0%) | 22,184 (30.5%) | 9677 (13.3%) | 2256 (3.1%) | ||

| Variable | Physical Health | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Very Good | Good | Average | Poor | Very Poor | p 1 | ||

| Fast food | Every day | 488 (16.4%) | 638 (21.5%) | 1149 (38.7%) | 494 (16.6%) | 198 (6.7%) | <0.001 |

| Several times a week | 3145 (9.9%) | 9730 (30.7%) | 13,980 (44.1%) | 4212 (13.3%) | 633 (2.0%) | ||

| Once a week | 7941 (11.9%) | 25,594 (38.5%) | 26,733 (40.2%) | 5660 (8.5%) | 573 (0.9%) | ||

| A few times a month | 26,936 (12.0%) | 89,590 (39.9%) | 89,598 (39.9%) | 16,910 (7.5%) | 1667 (0.7%) | ||

| Once a month | 27,987 (13.8%) | 85,948 (42.2%) | 75,218 (37.0%) | 13,090 (6.4%) | 1270 (0.6%) | ||

| Less than once a month | 70,430 (14.6%) | 202,050 (41.9%) | 174,976 (36.2%) | 32,090 (6.6%) | 3152 (0.7%) | ||

| Never | 31,686 (17.2%) | 75,607 (41.1%) | 62,346 (33.9%) | 12,788 (6.9%) | 1609 (0.9%) | ||

| Drinking beverages | Every day | 14,407 (10.3%) | 49,380 (35.3%) | 59,319 (42.4%) | 14,650 (10.5%) | 2024 (1.4%) | <0.001 |

| Several times a week | 16,662 (10.8%) | 59,366 (38.5%) | 63,857 (41.4%) | 13,122 (8.5%) | 1313 (0.9%) | ||

| Once a week | 9896 (12.3%) | 33,718 (42.0%) | 30,515 (38.0%) | 5557 (6.9%) | 557 (0.7%) | ||

| A few times a month | 25,255 (12.5%) | 84,038 (41.6%) | 77,863 (38.6%) | 13,561 (6.7%) | 1193 (0.6%) | ||

| Once a month | 13,426 (14.0%) | 40,826 (42.6%) | 34,789 (36.3%) | 6288 (6.6%) | 604 (0.6%) | ||

| Less than once a month | 44,053 (15.0%) | 124,916 (42.6%) | 104,714 (35.7%) | 17,987 (6.1%) | 1784 (0.6%) | ||

| I never drink such drinks | 44,915 (0.6%) | 96,913 (42.0%) | 72,943 (31.6%) | 14,079 (6.1%) | 1627 (0.7%) | ||

| Energy drinks | Three or more times a day | 721 (15.4%) | 1199 (25.5%) | 1936 (41.3%) | 7011 (4.9%) | 136 (2.9%) | <0.001 |

| One to two times a day | 1497 (11.5%) | 4114 (31.5%) | 5714 (43.7%) | 1532 (11.7%) | 205 (1.6%) | ||

| Several times a week | 4660 (12.7%) | 13,064 (35.5%) | 15,209 (41.4%) | 3355 (9.1%) | 480 (1.3%) | ||

| Once a week | 3337 (13.9%) | 9675 (40.2%) | 8972 (37.3%) | 1843 (7.7%) | 232 9 (1.0%) | ||

| A few times a month | 7900 (12.7%) | 24,119 (38.9%) | 24,361 (39.3%) | 5108 (8.2%) | 571 (0.9%) | ||

| Once a month | 6441 (13.7%) | 19,370 (41.1%) | 17,515 (37.2%) | 3403 (7.2%) | 400 (0.8%) | ||

| Less than once a month | 28,204 (14.0%) | 83,966 (41.6%) | 74,362 (36.8%) | 14,025 (6.9%) | 1444 (0.7%) | ||

| I never drink energy drinks | 115,856 (14.4%) | 333,651 (41.4%) | 295,932 (36.7%) | 55,277 (6.9%) | 5634 (0.7%) | ||

| Drinking alcohol | Two or more drinks a day | 3613 (11.2%) | 10,552 (32.8%) | 13,632 (42.4%) | 3809 (11.8%) | 562 (1.7%) | <0.001 |

| About one drink a day | 6486 (14.9%) | 18,217 (41.9%) | 15,899 (36.6%) | 2612 (6.0%) | 261 (0.6%) | ||

| Two or three drinks a week | 25,548 (15.9%) | 70,549 (43.8%) | 55,508 (34.4%) | 8824 (5.5%) | 739 (0.5%) | ||

| Two or three drinks a month | 27,438 (15.0%) | 78,640 (43.0%) | 65,396 (35.7%) | 10,588 (5.8%) | 952 (0.5%) | ||

| One drink a month or less | 31,962 (13.5%) | 93,046 (39.4%) | 91,260 (38.6%) | 18,027 (7.6%) | 1869 (0.8%) | ||

| I never drink alcohol | 22,551 (13.7%) | 56,755 (34.6%) | 64,480 (39.3%) | 17,730 (10.8%) | 2505 (1.5%) | ||

| Vegetables | Every day | 78,097 (46.3%) | 165,786 (33.9%) | 115,349 (26.0%) | 20,539 (24.1%) | 2227 (24.5%) | <0.001 |

| Several times a week | 63,879 (37.9%) | 214,037 (43.8%) | 193,689 (43.6%) | 34,638 (40.6%) | 3208 (35.3%) | ||

| Once a week | 9791 (5.8%) | 41,672 (8.5%) | 47,044 (10.6%) | 9626 (11.3%) | 970 (10.7%) | ||

| A few times a month | 11,925 (7.1%) | 49,700 (10.2%) | 61,554 (13.9%) | 12,949 (15.2%) | 1480 (16.3%) | ||

| Once a month | 1842 (1.1%) | 7635 (1.6%) | 10,608 (2.4%) | 2823 (3.3%) | 379 (4.2%) | ||

| Less than once month | 2283 (4.2%) | 8858 (1.8%) | 13,326 (3.0%) | 3825 (4.5%) | 596 (6.5%) | ||

| Never | 793 (0.5%) | 1467 (0.3%) | 2428 (0.5%) | 841 (1.0%) | 240 (2.6%) | ||

| Fruits | Every day | 78,535 (46.6%) | 183,567 (37.5%) | 132,318 (29.8%) | 22,227 (26.1%) | 2325 (25.6%) | <0.001 |

| Several times a week | 59,343 (35.2%) | 191,243 (39.1%) | 171,329 (38.6%) | 30,739 (36.1%) | 2914 (32.0%) | ||

| Once a week | 11,505 (6.8%) | 43,412 (8.9%) | 47,982 (10.8%) | 9785 (11.5%) | 917 (10.1%) | ||

| A few times a month | 12,559 (7.4%) | 49,233 (10.1%) | 60,539 (13.6%) | 13,133 (15.4%) | 1421 (15.6%) | ||

| Once a month | 2505 (1.5%) | 9312 (1.9%) | 12,735 (2.9%) | 3495 (4.1%) | 426 (4.7%) | ||

| Less than once a month | 3099 (1.8%) | 10,391 (2.1%) | 16,083 (3.6%) | 4763 (5.6%) | 824 (9.1%) | ||

| Never | 1063 (0.6%) | 1997 (0.4%) | 3013 (0.7%) | 1100 (1.3%) | 271 (3.0%) | ||

| Red meat | Every day | 5728 (5.3%) | 15,317 (4.9%) | 17,341 (5.9%) | 4110 (7.0%) | 489 (7.4%) | <0.001 |

| One to three times a week | 42,387 (39.2%) | 126,074 (40.7%) | 115,470 (39.5%) | 21,544 (36.7%) | 2181 (33.1%) | ||

| Once or twice a month | 51,598 (47.7%) | 143,146 (46.2%) | 129,471 (44.3%) | 25,550 (43.5%) | 2781 (42.2%) | ||

| Never | 8497 (7.9%) | 25,170 (8.1%) | 30,255 (10.3%) | 7572 (12.9%) | 1135 (17.2%) | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zweifler, G.; Zimny-Zając, A.; Babicki, M.; Kłoda, K.; Mazur, G.; Jankowska-Polańska, B.; Mastalerz-Migas, A.; Agrawal, S. Socio-Demographic Disparities in Diet and Their Association with Physical and Mental Well-Being: Million-Participant Cross-Sectional Study in Poland. Nutrients 2025, 17, 2924. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17182924

Zweifler G, Zimny-Zając A, Babicki M, Kłoda K, Mazur G, Jankowska-Polańska B, Mastalerz-Migas A, Agrawal S. Socio-Demographic Disparities in Diet and Their Association with Physical and Mental Well-Being: Million-Participant Cross-Sectional Study in Poland. Nutrients. 2025; 17(18):2924. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17182924

Chicago/Turabian StyleZweifler, Grażyna, Anna Zimny-Zając, Mateusz Babicki, Karolina Kłoda, Grzegorz Mazur, Beata Jankowska-Polańska, Agnieszka Mastalerz-Migas, and Siddarth Agrawal. 2025. "Socio-Demographic Disparities in Diet and Their Association with Physical and Mental Well-Being: Million-Participant Cross-Sectional Study in Poland" Nutrients 17, no. 18: 2924. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17182924

APA StyleZweifler, G., Zimny-Zając, A., Babicki, M., Kłoda, K., Mazur, G., Jankowska-Polańska, B., Mastalerz-Migas, A., & Agrawal, S. (2025). Socio-Demographic Disparities in Diet and Their Association with Physical and Mental Well-Being: Million-Participant Cross-Sectional Study in Poland. Nutrients, 17(18), 2924. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17182924