Nutritional Intervention for Sjögren Disease: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Eligibility Criteria

2.2. Databases and Search Strategy

2.3. Selection Process and Data Extraction

2.4. Quality Assessment

2.5. Data Analysis

2.6. Protocol and Registration

3. Results

3.1. Study Selection and General Characteristics of Included Studies

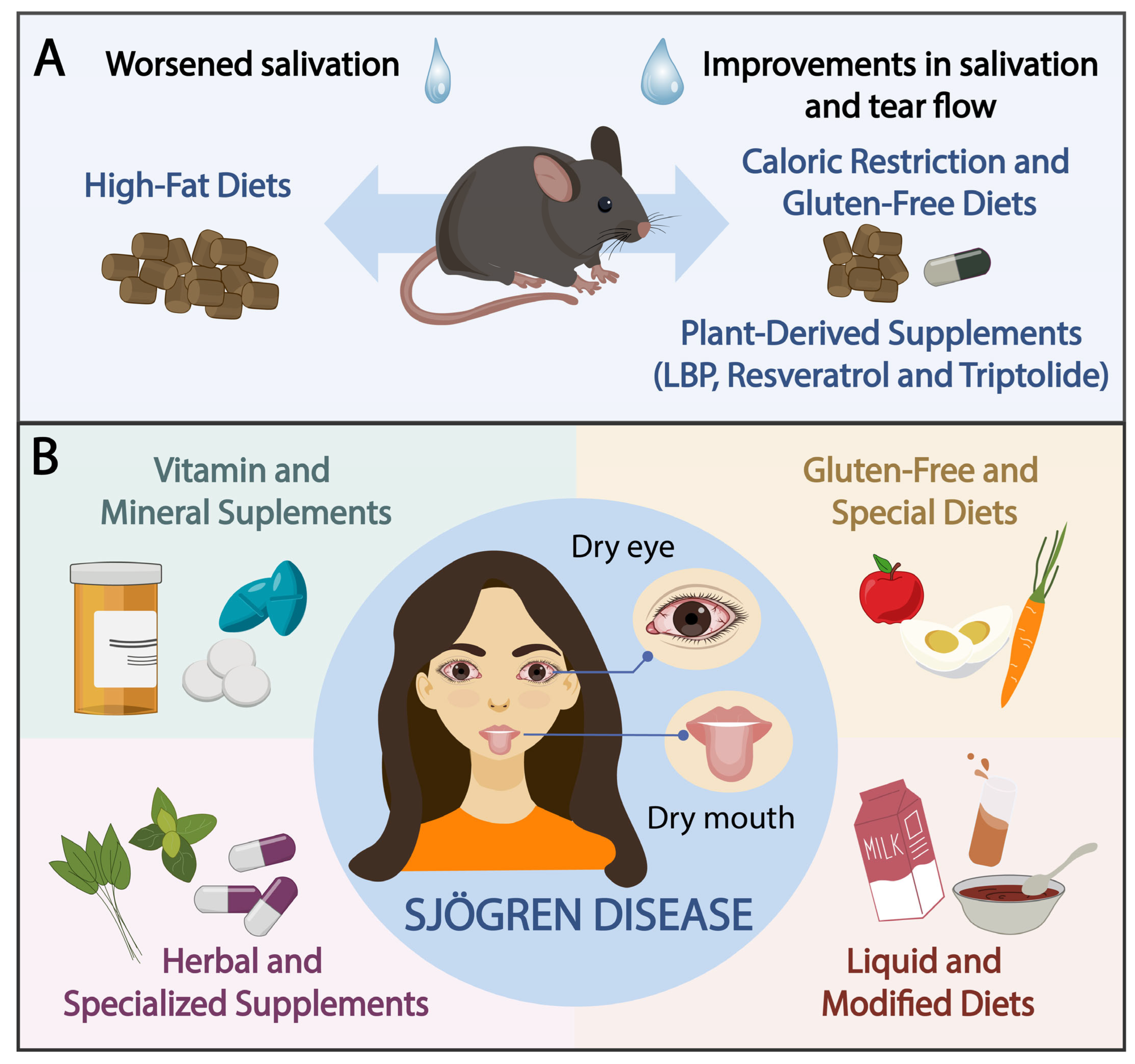

3.2. Animal Studies

3.3. Human Studies

3.3.1. Vitamin and Mineral Supplements

3.3.2. GF and Special Diets

3.3.3. Liquid and Modified Diets

3.3.4. Herbal and Specialized Supplements

3.4. Critical Appraisal

4. Discussion

- -

- -

- -

- -

- -

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Price, E.J.; Benjamin, S.; Bombardieri, M.; Bowman, S.; Carty, S.; Ciurtin, C.; Crampton, B.; Dawson, A.; Fisher, B.A.; Giles, I.; et al. British Society for Rheumatology guideline on management of adult and juvenile onset Sjögren disease. Rheumatology 2025, 64, 409–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parisis, D.; Chivasso, C.; Perret, J.; Soyfoo, M.S.; Delporte, C. Current state of knowledge on primary Sjögren’s syndrome, an autoimmune exocrinopathy. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 2299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brito-Zerón, P.; Baldini, C.; Bootsma, H.; Bowman, S.J.; Jonsson, R.; Mariette, X.; Sivils, K.; Theander, E.; Tzioufas, A.; Ramos-Casals, M. Sjögren syndrome. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers. 2016, 2, 16047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonsson, R. Disease mechanisms in Sjögren’s syndrome: What do we know? Scand. J. Immunol. 2022, 95, e13145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beydon, M.; McCoy, S.; Nguyen, Y.; Sumida, T.; Mariette, X.; Seror, R. Epidemiology of Sjögren syndrome. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 2024, 20, 158–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nocturne, G.; Mariette, X. Sjögren Syndrome-associated lymphomas: An update on pathogenesis and management. Br. J. Haematol. 2015, 168, 317–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramos-Casals, M.; Brito-Zerón, P.; Bombardieri, S.; Bootsma, H.; De Vita, S.; Dörner, T.; Fisher, B.A.; Gottenberg, J.-E.; Hernandez-Molina, G.; Kocher, A.; et al. EULAR recommendations for the management of Sjögren’s syndrome with topical and systemic therapies. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2020, 79, 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fox, R.I.; Fox, C.M.; Gottenberg, J.E.; Dörner, T. Treatment of Sjögren’s syndrome: Current therapy and future directions. Rheumatology 2021, 60, 2066–2074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Enger, T.B.; Palm, Ø.; Garen, T.; Sandvik, L.; Jensen, J.L. Oral distress in primary Sjögren’s syndrome: Implications for health-related quality of life. Eur. J. Oral Sci. 2011, 119, 474–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, S.; Sung, H.; Sepúlveda, D.; González, M.; Molina, C. Oral manifestations and their treatment in Sjögren’s syndrome. Oral Dis. 2014, 20, 153–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyamoto, S.T.; Valim, V.; Fisher, B.A. Health-related quality of life and costs in Sjögren’s syndrome. Rheumatology 2021, 60, 2588–2601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusthen, S.; Young, A.; Herlofson, B.B.; Aqrawi, L.A.; Rykke, M.; Hove, L.H.; Palm, Ø.; Jensen, J.L.; Singh, P.B. Oral disorders, saliva secretion, and oral health-related quality of life in patients with primary Sjögren’s syndrome. Eur. J. Oral Sci. 2017, 125, 65–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nesvold, M.B.; Jensen, J.L.; Hove, L.H.; Singh, P.B.; Young, A.; Palm, Ø.; Andersen, L.F.; Carlsen, M.H.; Iversen, P.O. Dietary intake, body composition, and oral health parameters among female patients with primary Sjögren’s syndrome. Nutrients 2018, 10, 866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, G.; Jolly, C.A. Nutrition and autoimmune disease. Nutr. Rev. 1998, 56 Pt 2, S161–S169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, S.M.; Pagovich, O.E.; Kriegel, M.A. Diet, microbiota and autoimmune diseases. Lupus 2014, 23, 518–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cermak, J.M.; Papas, A.S.; Sullivan, R.M.; Dana, M.R.; Sullivan, D.A. Nutrient intake in women with primary and secondary Sjögren’s syndrome. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2003, 57, 328–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szodoray, P.; Horvath, I.F.; Papp, G.; Barath, S.; Gyimesi, E.; Csathy, L.; Kappelmayer, J.; Sipka, S.; Duttaroy, A.K.; Nakken, B.; et al. The immunoregulatory role of vitamins A, D and E in patients with primary Sjogren’s syndrome. Rheumatology 2010, 49, 211–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, X.; Zhao, Z.; Wang, S.; Kang, J.; Zhang, M.; Bu, J.; Cai, X.; Jia, C.; Li, Y.; Li, K.; et al. High-fat diet-induced functional and pathologic changes in lacrimal gland. Am. J. Pathol. 2020, 190, 2387–2402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Machowicz, A.; Hall, I.; de Pablo, P.; Rauz, S.; Richards, A.; Higham, J.; Poveda-Gallego, A.; Imamura, F.; Bowman, S.J.; Barone, F.; et al. Mediterranean diet and risk of Sjögren’s syndrome. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2020, 38 (Suppl. 126), 216–221. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zhang, M.; Liang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Li, Y.; Shen, L.; Shi, G. High-fat diet-induced intestinal dysbiosis is associated with the exacerbation of Sjogren’s syndrome. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 916089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddaway, N.R.; Collins, A.M.; Coughlin, D.; Kirk, S. The role of google scholar in evidence reviews and its applicability to grey literature searching. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0138237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moola, S.; Munn, Z.; Tufunaru, C.; Aromataris, E.; Sears, K.; Sfetc, R.; Currie, M.; Lisy, K.; Qureshi, R.; Mattis, P.; et al. Chapter 7: Systematic reviews of etiology and risk. In JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis; Aromataris, E., Munn, Z., Eds.; JBI: Adelaide, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barker, T.H.; Stone, J.C.; Sears, K.; Klugar, M.; Tufanaru, C.; Leonardi-Bee, J.; Aromataris, E.; Munn, Z. The revised JBI critical appraisal tool for the assessment of risk of bias for randomized controlled trials. JBI Evid. Synth. 2023, 21, 494–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hooijmans, C.R.; Rovers, M.M.; de Vries, R.B.M.; Leenaars, M.; Ritskes-Hoitinga, M.; Langendam, M.W. SYRCLE’s risk of bias tool for animal studies. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2014, 14, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swanson, C.A.; Levy, J.A.; Morrow, W.J. Effect of low dietary lipid on the development of Sjögren’s syndrome and haematological abnormalities in (NZB x NZW)F1 mice. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 1989, 48, 765–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandrasekar, B.; McGuff, H.S.; Aufdermorte, T.B.; Troyer, D.A.; Talal, N.; Fernandes, G. Effects of calorie restriction on transforming growth factor beta 1 and proinflammatory cytokines in murine Sjogren’s syndrome. Clin. Immunol. Immunopathol. 1995, 76 Pt 1, 291–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoue, H.; Kishimoto, A.; Ushikoshi-Nakayama, R.; Hasaka, A.; Takahashi, A.; Ryo, K.; Muramatsu, T.; Ide, F.; Mishima, K.; Saito, I. Resveratrol improves salivary dysfunction in a non-obese diabetic (NOD) mouse model of Sjögren’s syndrome. J. Clin. Biochem. Nutr. 2016, 59, 107–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, Y.; Ji, W.; Lu, Y.; Wang, Y. Triptolide reduces salivary gland damage in a non-obese diabetic mice model of Sjögren’s syndrome via JAK/STAT and NF-κB signaling pathways. J. Clin. Biochem. Nutr. 2021, 68, 131–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haupt-Jorgensen, M.; Groule, V.; Reibel, J.; Buschard, K.; Pedersen, A.M.L. Gluten-free diet modulates inflammation in salivary glands and pancreatic islets. Oral Dis. 2022, 28, 639–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Xiao, J.; Duan, Y.; Miao, M.; Huang, B.; Chen, J.; Cheng, G.; Zhou, X.; Jin, Y.; He, J.; et al. Lycium barbarum polysaccharide ameliorates Sjögren’s syndrome in a murine model. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2021, 65, e2001118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, D.; Onodera, S.; Deng, S.; Alnujaydi, B.; Yu, Q.; Zhou, J. Alternate-day fasting ameliorates newly established Sjögren’s syndrome-like sialadenitis in non-obese diabetic mice. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 13791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Onodera, S.; Yu, Q.; Zhou, J. The impact of alternate-day fasting on the salivary gland stem cell compartments in non-obese diabetic mice with newly established Sjögren’s syndrome. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Cell Res. 2024, 1871, 119817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raffle, R.B. Sjögren’s disease associated with a nutritional deficiency syndrome. Br. Med. J. 1950, 1, 1470–1471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maclaurin, B.P.; Matthews, N.; Kilpatrick, J.A. Coeliac disease associated with auto-immune thyroiditis, Sjogren’s syndrome, and a lymphocytotoxic serum factor. Aust. N. Z. J. Med. 1972, 2, 405–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horrobin, D.F.; Campbell, A. Sjogren’s syndrome and the sicca syndrome: The role of prostaglandin E1 deficiency. Treatment with essential fatty acids and vitamin C. Med. Hypotheses 1980, 6, 225–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKendry, R.J. Treatment of Sjogren’s syndrome with essential fatty acids, pyridoxine and vitamin C. Prostaglandins Leukot. Med. 1982, 8, 403–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, A.; Gerner, N.; Palmvang, I.; Høier-Madsen, M. LongoVital in the treatment of Sjögren’s syndrome. Clin. Exp. Rheumatol. 1999, 17, 533–538. [Google Scholar]

- Vitali, C.; Bombardieri, S.; Moutsopoulos, H.M.; Balestrieri, G.; Bencivelli, W.; Bernstein, R.M.; Bjerrum, K.B.; Braga, S.; Coll, J.; de Vita, S.; et al. Preliminary criteria for the classification of Sjögren’s syndrome. Results of a prospective concerted action supported by the European Community. Arthritis Rheum. 1993, 36, 340–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peen, E.; Haga, H.J.; Haugen, A.J.; Kahrs, G.E.; Haugen, M. The effect of a liquid diet on salivary flow in primary Sjögren’s syndrome. Scand. J. Rheumatol. 2008, 37, 236–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vitali, C.; Bombardieri, S.; Jonsson, R.; Moutsopoulos, H.M.; Alexander, E.L.; Carsons, S.E.; Daniels, T.E.; Fox, P.C.; Fox, R.I.; Kassan, S.S.; et al. Classification criteria for Sjögren’s syndrome: A revised version of the European criteria proposed by the American-European Consensus Group. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2002, 61, 554–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, M.; Stark, P.C.; Palmer, C.A.; Gilbard, J.P.; Papas, A.S. Effect of omega-3 and vitamin E supplementation on dry mouth in patients with Sjögren’s syndrome. Spec. Care Dentist. 2010, 30, 225–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, C.Y.; Wang, C.C.; Chen, I.H.; Shiang, J.C.; Liu, M.Y.; Tsai, M.K. Hypokalemic paralysis as a presenting manifestation of primary Sjögren’s syndrome accompanied by vitamin D deficiency. Intern. Med. 2013, 52, 2351–2353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldner, B.; Staffier, K.L. Case series: Raw, whole, plant-based nutrition protocol rapidly reverses symptoms in three women with systemic lupus erythematosus and Sjögren’s syndrome. Front. Nutr. 2024, 11, 1208074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Rawi, Z.S.; Jalal, A.M.; Hameed, I.H. A randomized double-blind placebo-controlled clinical trial of fish oil (omega-3) in Sjogren’s syndrome patients in Erbil-Iraq. Mediterr. J. Rheumatol. 2024, 36, 92–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rhodus, N.L. Qualitative nutritional intake analysis of older adults with Sjogren’s syndrome. Gerodontology 1988, 7, 61–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, C.J.; Panush, R.S. Diets, dietary supplements, and nutritional therapies in rheumatic diseases. Rheum. Dis. Clin. N. Am. 1999, 25, 937–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semerano, L.; Julia, C.; Aitisha, O.; Boissier, M.C. Nutrition and chronic inflammatory rheumatic disease. Jt. Bone Spine 2017, 84, 547–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nobs, S.P.; Zmora, N.; Elinav, E. Nutrition regulates innate immunity in health and disease. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 2020, 40, 189–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwager, J.; Seifert, N.; Bompard, A.; Raederstorff, D.; Bendik, I. Resveratrol, EGCG and vitamins modulate activated T lymphocytes. Molecules 2021, 26, 5600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q. Triptolide and its expanding multiple pharmacological functions. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2011, 11, 377–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moudgil, K.D.; Venkatesha, S.H. The anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory activities of natural products to control autoimmune inflammation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 24, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chien, K.J.; Horng, C.T.; Huang, Y.S.; Hsieh, Y.H.; Wang, C.J.; Yang, J.S.; Lu, C.; Chen, F. Effects of Lycium barbarum (goji berry) on dry eye disease in rats. Mol. Med. Rep. 2018, 17, 809–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, K.; Luo, P.; Guo, Z.; Yang, L.; Pu, J.; Han, F.; Cai, F.; Tang, J.; Wang, X. Lipid metabolism: An emerging player in Sjögren’s syndrome. Clin. Rev. Allergy Immunol. 2025, 68, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mora, J.R.; Iwata, M.; von Andrian, U.H. Vitamin effects on the immune system: Vitamins A and D take centre stage. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2008, 8, 685–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radić, M.; Kolak, E.; Đogaš, H.; Gelemanović, A.; Nenadić, D.B.; Vučković, M.; Radić, J. Vitamin D and Sjögren’s disease: Revealing the connections-a systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutrients 2023, 15, 497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isola, S.; Gammeri, L.; Furci, F.; Gangemi, S.; Pioggia, G.; Allegra, A. Vitamin C supplementation in the treatment of autoimmune and onco-hematological diseases: From prophylaxis to adjuvant therapy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 7284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simopoulos, A.P. Omega-3 fatty acids in inflammation and autoimmune diseases. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 2002, 21, 495–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poggioli, R.; Hirani, K.; Jogani, V.G.; Ricordi, C. Modulation of inflammation and immunity by omega-3 fatty acids: A possible role for prevention and to halt disease progression in autoimmune, viral, and age-related disorders. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2023, 27, 7380–7400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castrejón-Morales, C.Y.; Granados-Portillo, O.; Cruz-Bautista, I.; Ruiz-Quintero, N.; Manjarrez, I.; Lima, G.; Hernández-Ramírez, D.F.; Astudillo-Angel, M.; Llorente, L.; Hernández-Molina, G. Omega-3 and omega-6 fatty acids in primary Sjögren’s syndrome: Clinical meaning and association with inflammation. Clin. Exp. Rheumatol. 2020, 38 (Suppl. 126), 34–39. [Google Scholar]

- da Nave, C.B.; Pereira, P.; Silva, M.L. The effect of polyunsaturated fatty acid (PUFA) supplementation on clinical manifestations and inflammatory parameters in individuals with Sjögren’s syndrome: A literature review of randomized controlled clinical trials. Nutrients 2024, 16, 3786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maarse, F.; Jager, D.H.J.; Alterch, S.; Korfage, A.; Forouzanfar, T.; Vissink, A.; Brand, H.S. Sjögren’s syndrome is not a risk factor for periodontal disease: A systematic review. Clin. Exp. Rheumatol. 2019, 37 (Suppl. 118), 225–233. [Google Scholar]

- Lerner, A.; Shoenfeld, Y.; Matthias, T. Adverse effects of gluten ingestion and advantages of gluten withdrawal in nonceliac autoimmune disease. Nutr. Rev. 2017, 75, 1046–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruzzese, V.; Scolieri, P.; Pepe, J. Efficacy of gluten-free diet in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Reumatismo 2021, 72, 213–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerner, A.; de Carvalho, J.F.; Kotrova, A.; Shoenfeld, Y. Gluten-free diet can ameliorate the symptoms of non-celiac autoimmune diseases. Nutr. Rev. 2022, 80, 525–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clemente-Suárez, V.J.; Beltrán-Velasco, A.I.; Redondo-Flórez, L.; Martín-Rodríguez, A.; Tornero-Aguilera, J.F. Global impacts of Western diet and its effects on metabolism and health: A narrative review. Nutrients 2023, 15, 2749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzel, A.; Muller, D.N.; Hafler, D.A.; Erdman, S.E.; Linker, R.A.; Kleinewietfeld, M. Role of “Western diet” in inflammatory autoimmune diseases. Curr. Allergy Asthma Rep. 2014, 14, 404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malesza, I.J.; Malesza, M.; Walkowiak, J.; Mussin, N.; Walkowiak, D.; Aringazina, R.; Bartkowiak-Wieczorek, J.; Mądry, E. High-fat, Western-style diet, systemic inflammation, and gut microbiota: A narrative review. Cells 2021, 10, 3164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, C.; Xiao, Q.; Fei, Y. A glimpse into the microbiome of Sjögren’s syndrome. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 918619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Carvalho, J.F.; Lerner, A.; Gonçalves, C.M.; Shoenfeld, Y. Sjögren syndrome associated with protein-losing enteropathy: Case-based review. Clin. Rheumatol. 2021, 40, 2491–2497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina, G.; Vera-Lastra, O.; Peralta-Amaro, A.L.; Jiménez-Arellano, M.P.; Saavedra, M.A.; Cruz-Domínguez, M.P.; Jara, L.J. Metabolic syndrome, autoimmunity and rheumatic diseases. Pharmacol. Res. 2018, 133, 277–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Augusto, K.L.; Bonfa, E.; Pereira, R.M.R.; Bueno, C.; Leon, E.P.; Viana, V.S.T.; Pasoto, S.G. Metabolic syndrome in Sjögren’s syndrome patients: A relevant concern for clinical monitoring. Clin. Rheumatol. 2016, 35, 639–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Servioli, L.; Maciel, G.; Nannini, C.; Crowson, C.S.; Matteson, E.L.; Cornec, D.; Berti, A. Association of smoking and obesity on the risk of developing primary Sjögren syndrome: A population-based cohort study. J. Rheumatol. 2019, 46, 727–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carubbi, F.; Alunno, A.; Mai, F.; Mercuri, A.; Centorame, D.; Cipollone, J.; Mariani, F.M.; Rossi, M.; Bartoloni, E.; Grassi, D.; et al. Adherence to the Mediterranean diet and the impact on clinical features in primary Sjögren’s syndrome. Clin. Exp. Rheumatol. 2021, 39 (Suppl. 133), 190–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.-L.; Gong, Y.; Qi, Y.-J.; Shao, Z.-M.; Jiang, Y.-Z. Effects of dietary intervention on human diseases: Molecular mechanisms and therapeutic potential. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2024, 9, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alwarith, J.; Kahleova, H.; Rembert, E.; Yonas, W.; Dort, S.; Calcagno, M.; Burgess, N.; Crosby, L.; Barnard, N.D. Nutrition interventions in rheumatoid arthritis: The potential use of plant-based diets. A review. Front. Nutr. 2019, 6, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knippenberg, A.; Robinson, G.A.; Wincup, C.; Ciurtin, C.; Jury, E.C.; Kalea, A.Z. Plant-based dietary changes may improve symptoms in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus 2022, 31, 65–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaaya, C.; Raad, E.; Kahale, F.; Chelala, E.; Ziade, N.; Maalouly, G. Adherence to Mediterranean diet and ocular dryness severity in Sjögren’s syndrome: A cross-sectional study. Med. Sci. 2025, 13, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pringle, S.; Wang, X.; Verstappen, G.M.P.J.; Terpstra, J.H.; Zhang, C.K.; He, A.; Patel, V.; Jones, R.E.; Baird, D.M.; Spijkervet, F.K.L.; et al. Salivary gland stem cells age prematurely in primary Sjögren’s syndrome. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019, 71, 133–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.-N.; Ou, T.-T.; Lin, C.-H.; Lin, Y.-Z.; Fang, T.-J.; Chen, Y.-J.; Tseng, C.-C.; Sung, W.-Y.; Wu, C.-C.; Yen, J.-H. NLRP3 gene polymorphisms in rheumatoid arthritis and primary Sjogren’s syndrome patients. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Xu, M.; Chen, Y.; Wu, S. Grp78 regulates NLRP3 inflammasome and participates in Sjogren’s syndrome. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2024, 140, 112815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duregon, E.; Pomatto-Watson, L.C.D.; Bernier, M.; Price, N.L.; de Cabo, R. Intermittent fasting: From calories to time restriction. Geroscience 2021, 43, 1083–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okawa, T.; Nagai, M.; Hase, K. Dietary intervention impacts immune cell functions and dynamics by inducing metabolic rewiring. Front. Immunol. 2021, 11, 623989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Procaccini, C.; de Candia, P.; Russo, C.; De Rosa, G.; Lepore, M.T.; Colamatteo, A.; Matarese, G. Caloric restriction for the immunometabolic control of human health. Cardiovasc. Res. 2024, 119, 787–2800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humphreys-Beher, M.G.; Brayer, J.; Yamachika, S.; Peck, A.B.; Jonsson, R. An alternative perspective to the immune response in autoimmune exocrinopathy: Induction of functional quiescence rather than destructive autoaggression. Scand. J. Immunol. 1999, 49, 7–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, H.D.; Schneyer, C.A. Salivary gland atrophy in rat induced by liquid diet. Proc. Soc. Exp. Biol. Med. 1964, 117, 789–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, S.; Nezu, A.; Tanimura, A.; Nakamichi, Y.; Yamamoto, T. Responses of salivary glands to intake of soft diet. J. Oral Biosci. 2022, 64, 210–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiboski, C.H.; Shiboski, S.C.; Seror, R.; Criswell, L.A.; Labetoulle, M.; Lietman, T.M.; Rasmussen, A.; Scofield, H.; Vitali, C.; Bowman, S.J.; et al. 2016 American College of Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatism Classification Criteria for primary Sjögren’s syndrome: A consensus and data-driven methodology involving three international patient cohorts. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2017, 69, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagi, R.; Kumar, S.S.; Sheth, M.; Deshpande, A.; Khan, J. Association between oral microbiome dysbiosis and Sjogren Syndrome. A systematic review of clinical studies. Arch. Oral Biol. 2025, 172, 106167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellando-Randone, S.; Russo, E.; Venerito, V.; Matucci-Cerinic, M.; Iannone, F.; Tangaro, S.; Amedei, A. Exploring the Oral Microbiome in Rheumatic Diseases, State of Art and Future Prospective in Personalized Medicine with an AI Approach. J. Pers. Med. 2021, 11, 625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, J.; Lee, A.; Lee, J.; Kwon, D.I.; Park, H.K.; Park, J.-H.; Jeon, S.; Baek, K.; Lee, J.; Park, S.-H.; et al. Dysbiotic oral microbiota and infected salivary glands in Sjögren’s syndrome. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0230667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tseng, Y.-C.; Liao, K.-S.; Lin, W.-T.; Li, C.; Chang, C.-B.; Hsu, J.-W.; Chan, C.-P.; Chen, C.-M.; Wang, H.-P.; Chien, H.-C.; et al. A human oral commensal-mediated protection against Sjögren’s syndrome with maintenance of T cell immune homeostasis and improved oral microbiota. NPJ Biofilms Microbiomes 2025, 11, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, J.L.; Yap, Y.-A.; McLeod, K.H.; Mackay, C.R.; Mariño, E. Dietary metabolites and the gut microbiota: An alternative approach to control inflammatory and autoimmune diseases. Clin. Transl. Immunol. 2016, 5, e82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osailan, S.M.; Pramanik, R.; Shirlaw, P.; Proctor, G.B.; Challacombe, S.J. Clinical assessment of oral dryness: Development of a scoring system related to salivary flow and mucosal wetness. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. 2012, 114, 97–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Study | Country | Sample | Animal Model | Sex | Age | Disease Features | Nutritional Intervention | Intervention Duration | Stimulated Salivary Flow Rate | Histological Analysis | Schirmer Test |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Swanson et al., 1989 [26] | USA | 60 cases and 24 controls | Weaned NZB × NZW mice | F | 3- to 4-week-old | The NZB/W mice also developed autoimmune-related exocrine gland disease, resembling the abnormalities observed in SD | Diets: (a) 20 animals: HSF (7.7% coconut oil, 1–3% corn oil); (b) 20 animals: HUF (9% corn oil); (c) 20 animals: LF (1.2% corn oil); Control group: 24 animals fed a conventional rodent diet. | 3 months | NI | Destructive infiltration of exocrine glands: HSF: 47%; HUF: 41%; LF: 23%; Control group: 25%. | HSF: 2.2 mm (0.73) HUF: 2.2 mm (0.97) LF 3.3 mm (0.78) Control group: 3.0 mm (1.6) |

| Chandrasekar et al., 1995 [27] | USA | NI | (NZB × NZW) F1 | F | 4-week-old | Mice developed age-associated sialoadenitis, characterized by the infiltration of inflammatory mononuclear cells in the salivary glands, resembling human SD | Mice were fed a semi-purified diet containing either 5% fat AL or 40% CR. The diet composition included the following ingredients: casein (20%), corn oil (5%), starch (32%), dextrose (33%), fiber (4.5%), DL-methionine (0.3%), choline chloride (0.2%), salt mixture (3.5%), and a vitamin mix (vitamin diet fortification) (1.5%). To compensate for decreased food intake, the CR diet was supplemented with twice the amount of the vitamin and mineral mixture. CR mice were initially fed 5–10% less than the AL group for the first two weeks, 10–20% less during the third and fourth weeks, and 40% less thereafter. | 3.5 (young) to 8.5 (old) months | NI | Young animals: AL and CR—presented normal salivary-gland tissues. Older animals: CR—patchy foci of mild chronic peri-acinar and periductal inflammation of 0.247 ± 0.120 (n = 12) and percentage area of inflammation 0.130 ± 0.067%; AL—dense confluent infiltrates of lymphocytes, with average focus score of 0.824 ± 0.152 and percentage area of inflammation 2.410 ± 0.793% (n = 12; p < 0.005, comparing AL and CR mice). | NI |

| Inoue et al., 2016 [28] | Japan | NI | NOD/shi mice | F | 6-week-old | NOD mice, in which loss of lacrimal and salivary-gland function occurred | The mice were orally administered the vehicle (Milli-Q) or resveratrol (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) at doses of 100 or 250 mg/kg using gastric intubation 6 days per week from 6 to 20 weeks of age (n = 6 mice/group). Resveratrol was dissolved in 0.2 mL of H2O for administration. | 16 weeks | The salivary flow rate was not altered by the resveratrol between 6 weeks and 20 weeks of age, whereas 250 mg/kg resveratrol showed protective effects on the hyposalivation observed in the NOD mice at age 22 weeks. | In the parotid and sublingual salivary glands, no lymphocyte infiltration was observed in any of the groups of NOD mice. The periductal inflammatory cell foci in submandibular glands were not affected by resveratrol administration. | NI |

| Guo et al., 2021 [29] | China | 48 | NOD mice | F | 8-week-old | The authors used NOD mice, as an animal model of SD | The NOD mice were administered triptolide by means of gastric gavage. The dosage selection for TP [10 µg/(kg/day), 20 µg/(kg/day), and 40 µg/(kg/day)] was determined based on a previous study. Forty-eight NOD mice were divided into 4 groups: Control group (vehicle) (n = 12), NOD mice treated with 10 µg/(kg/day) TP (n = 12), NOD mice treated with 20 µg/(kg/day) TP (n = 12), and NOD mice treated with 40 mg/(kg/day) TP (n = 12) | 90 days | The salivary flow rate of the control group decreased over time. With the increase in TP concentration, the difference between the TP group and the control group was larger. | Focus Score: Control = 3.1 ± 0.21; Triptolide 10 = 2.4 ± 0.18; Triptolide 20 = 1.8 ± 0.17; Triptolide 40 = 1.5 ± 0.19. | NI |

| Haupt-Jorgensen et al., 2022 [30] | Denmark | NI | NOD/BomTac mice | F | 3- to 13-week-old | NOD mice are a widely used model for T1D (type 1 diabetes and SD) | Breeding pairs of prediabetic NOD mice were fed a gluten-free modified Altromin diet (the GF diet was prepared by replacing the gluten-containing ingredients with meat protein) or a standard non-purified Altromin diet (STD). | 13 weeks | NI | Focus score: GF (score 0.7) and STD (score 3.8) diets (p = 0.124). Submandibular glands from GF versus STD mice: 47% (p = 0.042) fewer CD68+ cells and 49% (p = 0.037) fewer CD4+ cells. In the same organ, there were tendencies (p = 0.130–0.650) to demonstrating fewer CD20+ cells, more CD8+ cells and fewer VEGFR1+ and VEGFR2+ cells (NS). | NI |

| Wang et al., 2021 [31] | China | NI | NOD mice | F | 7-week-old | A NOD mouse model was used, as it spontaneously develops features resembling human SD, such as lymphocytic infiltration in the salivary glands, hyposalivation, and autoantibodies | Use of Lycium barbarum polysaccharide (LBP) by oral administration. Mice were randomized into four groups (eight per group): Low-dose LBP (LBP.L) (5 mg kg−1 d−1), High-dose LBP (LBP.H) (10 mg kg−1 d−1), Low-dose recombinant human IL-2 (LDIL-2, 25,000 IU/d), and Control (saline water). | 12 weeks | NOD mice treated with LBP had increased salivary flow rates compared with the control group. | LBP.L group (histology score: 1.88 ± 0.83, foci number: 0.92 ± 0.59). Control group (histology score: 3.38 ± 1.06, p = 0.014; foci number: 1.87 ± 0.92, p = 0.045; n = 8). LBP.H group (histology score: 2.38 ± 0.92, p = 0.206; foci number: 1.13 ± 0.53, p = 0.193). LDIL-2 treated group (histology score: 1.50 ± 0.76, p = 0.002; foci number: 0.50 ± 0.54, p = 0.002). | NI |

| Li et al., 2022 [32] | USA | NI | NOD mice | F | 10-week-old | NOD mice, a well-defined mouse model that recapitulates human SD | The mice were deprived of food every other day from 10 to 13 weeks of age (ADF). All mice had unrestricted access to water throughout the entire experiment. Control: standard chow AL diet. | 3 weeks | Mice in the ADF group exhibited higher salivary flow rate compared to the control group, suggesting the improvement of the salivary secretory function (p < 0.05). | H/E staining of submandibular gland sections showed significantly lower leukocyte focus numbers and infiltration areas in the mice with ADF than in the control mice (p < 0.05). | NI |

| Zhang et al., 2022 [20] | China | NI | WT and IL-14α transgenic mice (IL-14α TG) | M | NI | The authors used IL-14α transgenic mice (IL-14α TG), a mouse model that mimics the clinical features of SD in the same time frame as in humans. This mouse model not only shows lacrimal gland and salivary-gland inflammation but also shows systemic manifestations of the disease | Mice were fed a standard diet (SD, 10 kcal% fat, 1022) and a HFD (60 kcal% fat). | 11 months | The levels of salivary-gland secretions of the IL14 HFD mice were significantly lower than the levels of salivary-gland secretions in the WT group and the IL14 group. | The results showed that the IL14 HFD group developed the same submandibular gland (SMG) injuries as the WT HFD group. However, the IL14 HFD group showed more extensive and severe lymphocytic inflammatory infiltration of SMG. | Tear production was significantly decreased in both the WT HFD and the IL14 HFD groups, compared with comparable SD groups |

| Li et al., 2024 [33] | Japan | NI | NOD mice | F | 10-week-old | NOD mice with newly established SD | Mice were fed every other day (ADF) and age- and sex-matched mice were fed a standard chow AL diet (controls). | 3 weeks | NI | The authors conducted immunohistochemical analysis:

| NI |

| Author and Year of Publication | Country | Sample | Sex | Age | Sjögren Disease Criteria | Additional Disease Information | Nutrition Intervention | Intervention Duration | UWSFR | Stimulated Salivary Flow Rate | Schirmer Test | Perceived Improvement in Dryness |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Raffle, 1950 [34] | UK | 1 | F | 50 | NI | Symptoms: vague rheumatic pains, weakness, lack of appetite and energy, pronounced facial swelling at the parotid regions, swelling under the chin, dry mouth, dysphagia, soreness of the tongue. | First, vitamin A, 150,000 units daily. Then, vitamin A stopped, and ferrous sulfate 18 g daily started. Then, “Beplex” capsules, six per day, were given (6 mg of thiamin hydrochloride, 4.8 mg. of riboflavin, and 60 mg. of nicotinic acid). | NI | NI | NI | NI | No improvement on the buccal condition, but the patient subjectively felt better. |

| Maclaurin et al., 1972 [35] | New Zealand | 1 | F | 73 | NI | Dryness and soreness of the eyes and mouth for one year. Schirmer’s test confirmed diminished tear secretion. | GF diet and treatment with vitamin B12 by injection, folic acid, calcium, and other vitamins. | 2 months | NI | NI | Improvement in tear secretion by Schirmer’s test | Dry mouth did not improve, improvement in general well-being. |

| Horrobin and Campbell, 1980 [36] | Canada | 5 | 1 F 4 NI | 52 4 NI | NI | One patient with a history of classic moderate rheumatoid arthritis and history of dry mouth and dry eyes, and the four others with long-established SD. | Intake of high-dose (7.5 g/day) vitamin C for a year, with 50 mg/day pyridoxine and 6 × 0.6 mL Evening Primrose Oil capsules per day. | 12 months | NI | NI | NI | All five patients had substantial improvements in tear and saliva production. |

| McKendry, 1982 [37] | Canada | 10 | NI | NI | NI | Patients presenting with subjective oral and ocular dryness. | Vitamin C 3.0 g daily and Evening Primrose Oil 6 × 500 mgs. capsules daily for six weeks. Pyridoxine 100 mgs. daily was added to the regimen from week 6 to week 10. At week 10, the Evening Primrose Oil. and Pyridoxine were discontinued and the dose of Vitamin C was tapered to zero over four weeks. | 16 weeks | NI | NI | NI. | One patient: subjective and objective evidence of improved oral and ocular lubrication. One patient: subjective improvement without improvement in Schirmer’s test. One patient: improvement in Schirmer’s test without subjective improvement. The others had no improvement |

| Pedersen et al., 1999 [38] | Denmark | 40 | 39 F 1 M | 60 (range 30–85) | The diagnosis was based on the criteria proposed by Vitali et al. (1993) [39] | NI | Three tablets of Longo Vital at breakfast. Group A: LV for the first 4 months; Group B: LV for the last 4 months. | 8 months (LV: 4 months/placebo: 4 months) | Group A—Significant increase in 4 months of LV (p < 0.001)/Group B—no significant changes in either period | Group A—stimulated salivary flow did not change on LV but increased on the subsequent 4 months of placebo (p < 0.05)/Group B—stimulated salivary flow increased only on LV (p < 0.05) | No significant changes | NI |

| Peen et al., 2008 [40] | Denmark | Patients: 23; Controls: 23 (matched age and sex) | 21 F 2 M | 56.6 (range 34–73) | Patients fulfilling the criteria for SD proposed by the American–European Consensus Group 2002 [41] | NI | Liquid diet avoiding mastication. The patients were also offered a free fluid dietary supplement in 200 mL boxes containing 1.5 kcal/mL, including 5.6 g protein, 18.8 g carbohydrates, and 5.8 g fat per 100 mL (Fresubin Energy, Fresenius Kabi, Bad Homburg, Germany), to a maximum of 600 mL/day. Controls: not on diet. | 4 weeks | Patients: week 1: 1.18 (0.73–2.03); week 4: 1.70 (0.95–2.69) p value: 0.02/Controls: week 1: 0.47 (0.25–0.84); week 4: 0.47 (0.02–1.05) p value: NS. | NI | Patients: week 1: 3.3 (0.39–4.95); week 4: 7.05 (2.39–6.55) p value: 0.05/Controls: week 1: 16.10 (6.64–26.31); week 4: 9.71 (4.11–12.41) p value: NS. | Salivary flow increased significantly in the 23 patients on the liquid diet for 4 weeks. |

| Singh et al., 2010 [42] | USA | 61 | 57 F 4 M | 61 (mean age) | Biopsy: NI/Focus score: NI/Anti-SSA (Ro): NI/Salivary flow: zero/Schirmer’s test: NI/Xerostomia: all patients had subjective complaints of dry mouth/Xeropthalmia: NI | All patients were on muscarinic agonists for at least 3 months. | Placebo (wheat germ oil): 23 subjects. TheraTears nutrition (n-3 supplement): 38 subjects. (TheraTears nutrition contains 1000 mg of flaxseed oil, 450 mg of EPA, 300 mg of DHA, 163 mg of vitamin E as d-alpha tocopherol, and 20 mg of mixed tocopherol concentrate.) One capsule per day, taken with breakfast. | 3 months | n-3 group: UWSFR increased significantly (SD), 0.076 (0.09) mL/min at baseline to 0.140 (0.18) mL/min at 3 months p = 0.029. Wheat germ oil: the mean (SD) UWSFR increased slightly from 0.065 (0.08) mL/min at baseline to 0.094 (0.11) mL/min at 3 months p = 0.135. | n-3 group: 0.776 (0.74) mL/min at baseline to 1.018 (1.08) mL/min at 3 months p = 0.026. Wheat germ oil: the mean (SD) US increased slightly from 0.919 (0.69) at baseline to 1.02 (0.76) mL/min at 3 months p = 0.316. | No significant changes | Perceived improvement in dry mouth was evaluated with VAS, and it was significant in both groups. |

| Liao et al., 2013 [43] | Taiwan | 1 | M | 49 | Biopsy: NI/Focus score: NI/Anti-SSA (Ro): positive/Salivary flow: NI/Schirmer’s test: NI/Xerostomia: positive/Xeropthalmia: positive | Anti-La SSB: positive/antinuclear antibodies: positive (1:2560), delayed saliva excretion on salivary scintigraphy. Other symptoms: profound hypokalemia, abnormal renal function with hyperphosphaturia, and hypocalcemia. | The patient was placed on potassium citrate (45 mEq/day) and active vitamin D3 (0.25 μg/d) therapy to treat the hypokalemia and vitamin D deficiency, respectively. | NI | NI | NI | NI | The patient experienced no further sicca symptoms or paralysis during outpatient department follow-up treatment. |

| Goldner et al., 2024 [44] | USA | 3 | F | 40, 54, and 45 | NI | Patient 1: photosensitivity, fatigue, pain in the legs, dry skin, dry eye, dry mouth, stomach cramping, diarrhea, pelvic pain. Patient 2: photosensitivity; butterfly rash; constant fatigue; joint stiffness in the fingers, elbows, and knees; severe dry mouth and dry eye; eye inflammation; neuropathy. Patient 3: Flu-like symptoms, migraines, intermittent dizziness, weakness, dry mouth, recurrent nerve pain in skin, fatigue, light sensitivity, eye pain, trigeminal neuralgia. | Initial RRP—Include: raw vegetables (unlimited); focus on high intake of leafy greens and cruciferous vegetables, fruits, whole and ground flax and chia seeds, cold-pressed flaxseed oil, water, and vitamin B12 and D supplementation. Eliminate: all animal products, added oils, processed foods, added sugars, cooked foods, grains, and legumes. Maintenance phase—Include: vegetables (recommended 75% raw), fruits (no recommended restrictions), seeds and nuts, whole and ground flax and chia seeds, water, intact and whole grains, legumes, and vitamin B12 and D supplementation. Eliminate: all animal products, added oils, processed foods, added sugars, and alcohol. | Initial RRP: 4 weeks | NI | NI | NI | Dry mouth and eyes resolved immediately (≤1 month) after start of RRP in all 3 patients. Other symptoms also resolved with the continuation of the diet. |

| Al-Rawi et al., 2024 [45] | Iraq | 104 | 99 F 5 M | Group 1: 53.4 ± 12.4; Group 2: 52.6 ± 11.3 | Based on the 2016 diagnostic criteria from ACR/EULAR | NI | Group 1 was given omega-3 dietary supplements. Group 2: placebo (two capsules daily). | 2 months | UWSFR at baseline (mean): Group 1: 0.99 mL/min; Group 2: 1.0 mL/min (p = 0.989). UWSFR at the last visit (mean): Group 1: 2.07 mL/min; Group 2: 1.55 mL/min (p = 0.053). | NI | Group 1: Baseline (mean): 2.38 mm; Last visit (mean): 6.63 mm (p < 0.001). Group 2: Baseline (mean): 2.68 mm; Last visit (mean): 5.58 mm (p = 0.01). | Improvements in eye symptoms including itching, mucous discharge, and photophobia. Improvement was noted in the xerostomia inventory. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Castro, F.L.A.d.L.; Heredia, J.E.; Schuch, L.F.; de Arruda, J.A.A.; Castro, M.A.A.; Calderaro, D.C.; de Oliveira, M.C.; de Sousa, S.F.; Silva, T.A. Nutritional Intervention for Sjögren Disease: A Systematic Review. Nutrients 2025, 17, 2743. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17172743

Castro FLAdL, Heredia JE, Schuch LF, de Arruda JAA, Castro MAA, Calderaro DC, de Oliveira MC, de Sousa SF, Silva TA. Nutritional Intervention for Sjögren Disease: A Systematic Review. Nutrients. 2025; 17(17):2743. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17172743

Chicago/Turabian StyleCastro, Fernanda Luiza Araújo de Lima, Joyce Elisa Heredia, Lauren Frenzel Schuch, José Alcides Almeida de Arruda, Maurício Augusto Aquino Castro, Débora Cerqueira Calderaro, Marina Chaves de Oliveira, Sílvia Ferreira de Sousa, and Tarcília Aparecida Silva. 2025. "Nutritional Intervention for Sjögren Disease: A Systematic Review" Nutrients 17, no. 17: 2743. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17172743

APA StyleCastro, F. L. A. d. L., Heredia, J. E., Schuch, L. F., de Arruda, J. A. A., Castro, M. A. A., Calderaro, D. C., de Oliveira, M. C., de Sousa, S. F., & Silva, T. A. (2025). Nutritional Intervention for Sjögren Disease: A Systematic Review. Nutrients, 17(17), 2743. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17172743