Association of Meat Attachment with Intention to Reduce Meat Consumption Among Young Adults: Moderating Role of Environmental Attitude

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design and Participants

2.2. Survey Questionnaire

2.3. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Participants’ Socio-Demographic Characteristics

3.2. Reliability of Multi-Item Measurements

3.3. Associations Between Meat Attachment and Intention to Reduce Meat Consumption

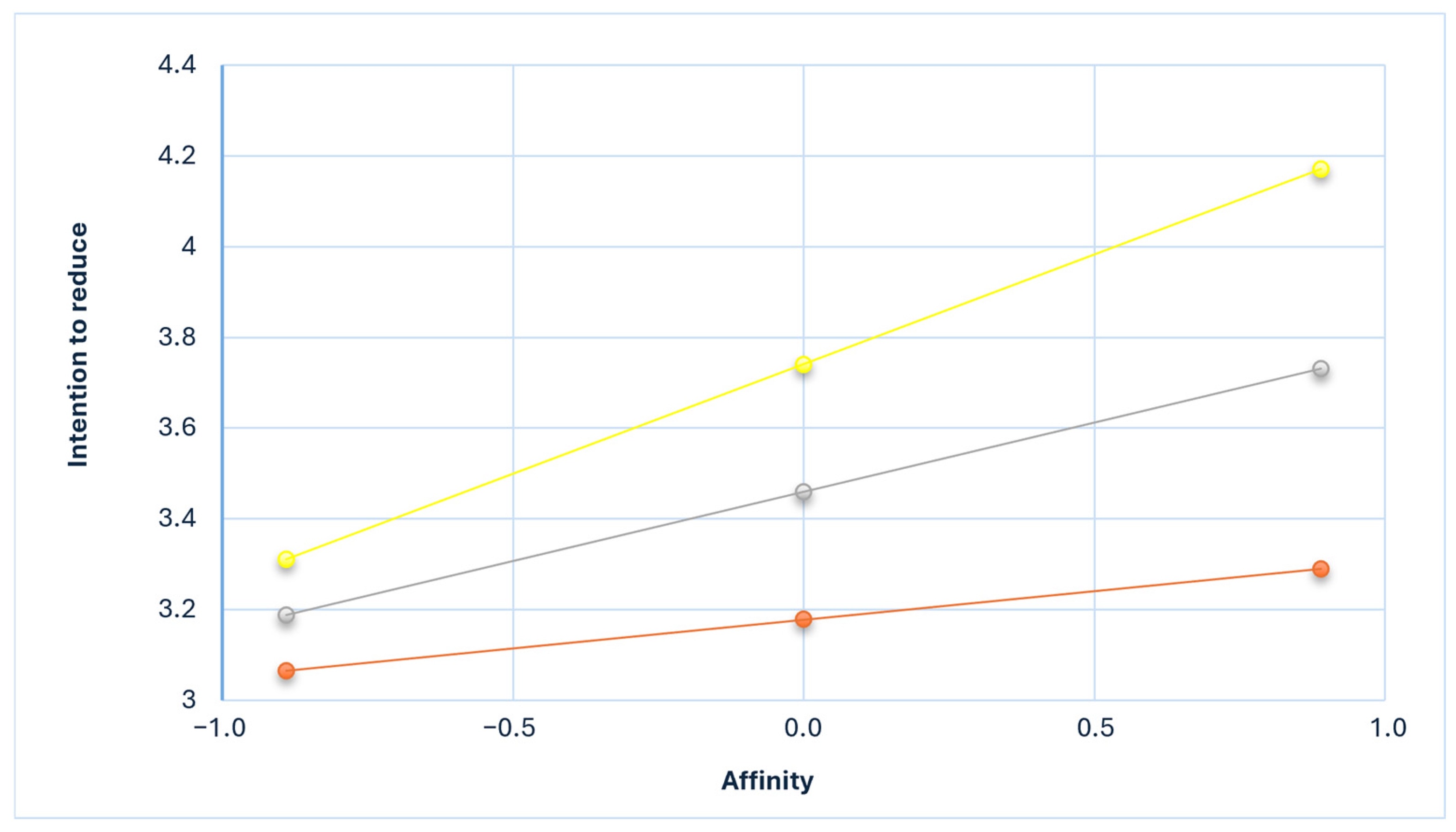

3.4. Moderating Effect of Environmental Attitude Between Meat Attachment and Intention to Reduce Meat Consumption

4. Discussion

4.1. Associations Between Meat Attachment and Intention to Reduce Meat Consumption

4.2. Moderating Effect of Environmental Attitude Between Meat Attachment and Intention to Reduce Meat Consumption

4.3. Study Implications

4.4. Study Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Survey Questionnaire

| Classification | Strongly Disagree | Strongly Agree | |

| Hedonism | To eat meat is one of the good pleasures in life | :___1___:___2___:___3___:___4___:___5___: | |

| I love meals with meat | :___1___:___2___:___3___:___4___:___5___: | ||

| I’m a big fan of meat | :___1___:___2___:___3___:___4___:___5___: | ||

| A good steak is without comparison | :___1___:___2___:___3___:___4___:___5___: | ||

| Affinity | By eating meat I’m reminded of the death and suffering of animals | :___1___:___2___:___3___:___4___:___5___: | |

| To eat meat is disrespectful towards life and the environment | :___1___:___2___:___3___:___4___:___5___: | ||

| I feel bad when I think of eating meat | :___1___:___2___:___3___:___4___:___5___: | ||

| Meat reminds me of diseases | :___1___:___2___:___3___:___4___:___5___: | ||

| Entitlement | To eat meat is an unquestionable right of every person | :___1___:___2___:___3___:___4___:___5___: | |

| According to our position in the food chain, we have the right to eat meat | :___1___:___2___:___3___:___4___:___5___: | ||

| Eating meat is a natural and undisputable practice | :___1___:___2___:___3___:___4___:___5___: | ||

| Dependence | I don’t picture myself without eating meat regularly | :___1___:___2___:___3___:___4___:___5___: | |

| If I couldn’t eat meat I would feel weak | :___1___:___2___:___3___:___4___:___5___: | ||

| I would feel fine with a meatless diet | :___1___:___2___:___3___:___4___:___5___: | ||

| If I was forced to stop eating meat I would feel sad | :___1___:___2___:___3___:___4___:___5___: | ||

| If I was forced to stop eating meat I would feel sad | :___1___:___2___:___3___:___4___:___5___: | ||

| Items | Strongly Disagree | Strongly Agree |

| The environmental crisis facing humanity is very serious. | :___1___:___2___:___3___:___4___:___5___: | |

| Plants and animals are equally precious beings, just like people. | :___1___:___2___:___3___:___4___:___5___: | |

| If the destruction of nature continues as it is now, we will soon experience a serious environmental disaster. | :___1___:___2___:___3___:___4___:___5___: | |

| Environmental pollution is becoming more serious, but there is no need to worry because nature has an excellent ability to purify itself. | :___1___:___2___:___3___:___4___:___5___: | |

| Nature is very resilient and can be utilized to suit human needs. | :___1___:___2___:___3___:___4___:___5___: | |

| I feel guilty when I do something harmful to the environment. | :___1___:___2___:___3___:___4___:___5___: | |

| I do not believe that my daily actions and lifestyle are causing climate crisis. | :___1___:___2___:___3___:___4___:___5___: | |

| I get angry when I see the environment being polluted due to our careless behaviors. | :___1___:___2___:___3___:___4___:___5___: | |

| I am willing to share information about environmental issues with my family and friends. | :___1___:___2___:___3___:___4___:___5___: | |

| Even if it is not immediately effective, personal sacrifice and volunteer to reduce environmental pollution are necessary. | :___1___:___2___:___3___:___4___:___5___: | |

| Do you have an intention to reduce meat consumption? | Very unlikely | Very likely |

| :___1___:___2___:___3___:___4___:___5___: | ||

| Please indicate your sex | ① Male ② Female |

| Please write down your age | Age: |

| Please indicate the highest level of education you have completed |

|

| Please indicate the level of average monthly household income (KRW) |

|

| What is your current employment status? |

|

| What is your Height and Weight? | ________cm ________kg |

References

- Godfray, H.C.J.; Aveyard, P.; Garnett, T.; Hall, J.W.; Key, T.J.; Lorimer, J.; Pierrehumbert, R.T.; Scarborough, P.; Springmann, M.; Jebb, S.A. Meat consumption, health, and the environment. Science 2018, 361, eaam5324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tilman, D.; Clark, M. Global diets link environmental sustainability and human health. Nature 2014, 515, 518–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mekonnen, M.M.; Gerbens-Leenes, W. The water footprint of global food production. Water 2020, 12, 2696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mekonnen, M.M.; Hoekstra, A.Y. A global assessment of the water footprint of farm animal products. Ecosystems 2012, 15, 401–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolk, A. Potential health hazards of eating red meat. J. Intern. Med. 2017, 281, 106–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallström, E.; Carlsson-Kanyama, A.; Börjesson, P. Environmental impact of dietary change: A systematic review. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 91, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satija, A.; Hu, F.B. Plant-based diets and cardiovascular health. Trends Cardiovasc. Med. 2018, 28, 437–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Springmann, M.; Godfray, H.C.J.; Rayner, M.; Scarborough, P. Analysis and valuation of the health and climate change co-benefits of dietary change. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, 4146–4151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuso, P.J.; Ismail, M.H.; Ha, B.P.; Bartolotto, C. Nutritional update for physicians: Plant-based diets. Perm. J. 2013, 17, 61–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Plant-Based Diets and Their Impact on Health, Sustainability and the Environment: A Review of Evidence; WHO Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2021. Available online: https://www.who.int/europe/publications/i/item/WHO-EURO-2021-4007-43766-61591 (accessed on 10 June 2023).

- FAO. Food Outlook—Biannual Report on Global Food Markets 2025; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Parlasca, M.C.; Qaim, M. Meat consumption and sustainability. Annu. Rev. Resour. Econ. 2022, 14, 17–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD; FAO. OECD-FAO Agricultural Outlook 2025-2034; OECD: Paris, France; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Moon, S.; Popkin, B.M. The nutrition transition in South Korea. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2000, 71, 44–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korea Rural Economic Institute (KREI). Agricultural Outlook 2023; Korea Rural Economic Institute (KREI): Naju, Republic of Korea, 2023; Available online: https://library.krei.re.kr/pyxis-api/1/digital-files/3a5a1dd0-69f5-4dd2-8f5f-3d2454eecd0c (accessed on 10 June 2023).

- Graça, J.; Calheiros, M.M.; Oliveira, A. Attached to meat? (Un)Willingness and intentions to adopt a more plant-based diet. Appetite 2015, 95, 113–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryant, C.; Szejda, K.; Parekh, N.; Deshpande, V.; Tse, B. A survey of consumer perceptions of plant-based and clean meat in the USA, India, and China. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2019, 3, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Circus, V.E.; Robison, R. Exploring perceptions of sustainable proteins and meat attachment. Br. Food J. 2019, 121, 533–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graça, J.; Oliveira, A.; Calheiros, M.M. Meat, beyond the plate. Data-driven hypotheses for understanding consumer willingness to adopt a more plant-based diet. Appetite 2015, 90, 80–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graça, J.; Godinho, C.A.; Truninger, M. Reducing meat consumption and following plant-based diets: Current evidence and future directions to inform integrated transitions. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 91, 380–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lentz, G.; Connelly, S.; Mirosa, M.; Jowett, T. Gauging attitudes and behaviours: Meat consumption and potential reduction. Appetite 2018, 127, 230–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.F. Consumer food choice motives and willingness to try plant-based meat: Moderating effect of meat attachment. Br. Food J. 2024, 126, 1301–1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grundy, E.A.C.; Slattery, P.; Saeri, A.K.; Watkins, K.; Houlden, T.; Farr, N.; Askin, H.; Lee, J.; Mintoft-Jones, A.; Cyna, S.; et al. Interventions that influence animal-product consumption: A meta-review. Future Foods 2022, 5, 100111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwasny, T.; Dobernig, K.; Riefler, P. Towards reduced meat consumption: A systematic literature review of intervention effectiveness, 2001–2019. Appetite 2022, 168, 105739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Sabate, R.; Sabaté, J. Consumer attitudes towards environmental concerns of meat consumption: A systematic review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vainio, A.; Irz, X.; Hartikainen, H. How effective are messages and their characteristics in changing behavioural intentions to substitute plant-based foods for red meat? The mediating role of prior beliefs. Appetite 2018, 125, 217–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verain, M.C.D.; Sijtsema, S.J.; Dagevos, H.; Antonides, G. Attribute segmentation and communication effects on healthy and sustainable consumer diet intentions. Sustainability 2017, 9, 743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korea Environment Institute. Public Attitudes Towards the Environment—2016 Survey; Korea Environment Institute (KEI): Sejong, Republic of Korea, 2016; Available online: https://library.kei.re.kr/pyxis-api/1/digital-files/92cfff3c-8d12-4f6a-9afd-ea0f7d809f53 (accessed on 3 June 2023).

- Park, S. Analysis of the Factors Affecting the Environmental Consciousness of the Environmental Task Forces Soldiers. Ph.D. Thesis, Seoul National University, Graduate School of Environment Studies, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Woo, H.; Eom, B.; Moon, Y. Development and verification of questionnaire for measurement of environmental attitude. J. Environ. Sci. Int. 1999, 8, 559–568. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach, 3rd ed; The Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Aiken, L.S.; West, S.G.; Reno, R.R. Multiple Regression: Testing and Interpreting Interactions; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Roozen, I.; Raedts, M. What determines omnivores’ meat consumption and their willingness to reduce the amount of meat they eat? Nutr. Health 2023, 29, 347–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szczebyło, A.; Halicka, E.; Rejman, K.; Kaczorowska, J. Is eating less meat possible? Exploring the willingness to reduce meat consumption among millennials working in Polish cities. Foods 2022, 11, 358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piazza, J.; Ruby, M.B.; Loughnan, S.; Luong, M.; Kulik, J.; Watkins, H.M.; Seigerman, M. Rationalizing meat consumption. The 4Ns. Appetite 2015, 91, 114–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, O.; Scrimgeour, F. Willingness to adopt a more plant-based diet in China and New Zealand: Applying the theories of planned behaviour, meat attachment and food choice motives. Food Qual. Prefer. 2021, 93, 104294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kühn, D.; Profeta, A.; Krikser, T.; Heinz, V. Adaption of the meat attachment scale (MEAS) to Germany: Interplay with food neophobia, preference for organic foods, social trust and trust in food technology innovations. Agric. Food Econ. 2023, 11, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowsett, E.; Semmler, C.; Bray, H.; Ankeny, R.A.; Chur-Hansen, A. Neutralising the meat paradox: Cognitive dissonance, gender, and eating animals. Appetite 2018, 123, 280–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoll-Kleemann, S.; Schmidt, U.J. Reducing meat consumption in developed and transition countries to counter climate change and biodiversity loss: A review of influence factors. Reg. Environ. Change 2017, 17, 1261–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunst, J.R.; Palacios Haugestad, C.A.P. The effects of dissociation on willingness to eat meat are moderated by exposure to unprocessed meat: A cross-cultural demonstration. Appetite 2018, 120, 356–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Dijk, B.; Jouppila, K.; Sandell, M.; Knaapila, A. No meat, lab meat, or half meat? Dutch and Finnish consumers’ attitudes toward meat substitutes, cultured meat, and hybrid meat products. Food Qual. Prefer. 2023, 108, 104886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartmann, C.; Lazzarini, G.; Funk, A.; Siegrist, M. Measuring consumers’ knowledge of the environmental impact of foods. Appetite 2021, 167, 105622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krizanova, J.; Rosenfeld, D.L.; Tomiyama, A.J.; Guardiola, J. Pro-environmental behaviour predicts adherence to plant-based diets. Appetite 2021, 163, 105243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Birch, D.; Memery, J.; de Silva Kanakaratne, M. The mindful consumer: Balancing egoistic and altruistic motivations to purchase local food. J. Retailing Con. Serv. 2018, 40, 221–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Profeta, A.; Baune, M.C.; Smetana, S.; Bornkessel, S.; Broucke, K.; Van Royen, G.; Enneking, U.; Weiss, J.; Heinz, V.; Hieke, S.; et al. Preferences of German consumers for meat products blended with plant-based proteins. Sustainability 2021, 13, 650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turnes, A.; Pereira, P.; Cid, H.; Valente, A. Meat consumption and availability for its reduction by health and environmental concerns: A pilot study. Nutrients 2023, 15, 3080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verain, M.C.D.; Dagevos, H. Comparing meat abstainers with avid meat eaters and committed meat reducers. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 1016858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jay, J.A.; D’Auria, R.; Nordby, J.C.; Rice, D.A.; Cleveland, D.A.; Friscia, A.; Kissinger, S.; Levis, M.; Malan, H.; Rajagopal, D.; et al. Reduction of the carbon footprint of college freshman diets after a food-based environmental science course. Clim. Change 2019, 154, 547–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Austgulen, M.H.; Skuland, S.E.; Schjøll, A.; Alfnes, F. Consumer readiness to reduce meat consumption for the purpose of environmental sustainability: Insights from Norway. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lea, E.J.; Crawford, D.; Worsley, A. Public views of the benefits and barriers to the consumption of a plant-based diet. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2006, 60, 828–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macdiarmid, J.I.; Douglas, F.; Campbell, J. Eating like there’s no tomorrow: Public awareness of the environmental impact of food and reluctance to eat less meat as part of a sustainable diet. Appetite 2016, 96, 487–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hopwood, C.J.; Stahlmann, A.G.; Bleidorn, W.; Thielmann, I. Personality, self-knowledge, and meat reduction intentions. J. Pers. 2024, 92, 1006–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Boer, J.; Schösler, H.; Boersema, J.J. Climate change and meat eating: An inconvenient couple? J. Environ. Psychol. 2013, 33, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergkvist, L.; Rossiter, J.R. The predictive validity of multiple-item versus single-item measures of the same constructs. J. Mark. Res. 2007, 44, 175–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Classification | n | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Male | 696 | 47.1 |

| Female | 782 | 52.9 | |

| Education | High school graduation | 170 | 11.5 |

| College/university students | 516 | 34.9 | |

| College/university graduation | 706 | 47.8 | |

| Graduate students or above | 86 | 5.8 | |

| Occupation | Employed | 696 | 47.1 |

| College/university or graduate students | 524 | 35.5 | |

| Unemployed | 258 | 17.5 | |

| Monthly household income (USD) (1) | <790 (lowest) | 337 | 22.8 |

| ≥790 and <2371 (low) | 616 | 41.7 | |

| ≥2371 and <3952 (middle) | 283 | 19.1 | |

| ≥3952 (high) | 242 | 16.4 | |

| BMI | Underweight | 125 | 8.5 |

| Normal weight | 772 | 52.2 | |

| Overweight/obesity | 581 | 39.3 | |

| Total | 1478 | 100 | |

| Classification | No. of Items | Cronbach’s α | Mean | S.D. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hedonism | 4 | 0.891 | 3.56 | 0.94 |

| Affinity | 4 | 0.822 | 2.13 | 0.85 |

| Entitlement | 3 | 0.835 | 3.17 | 0.95 |

| Dependence | 5 | 0.785 | 3.07 | 0.81 |

| Environmental attitude | 10 | 0.804 | 3.84 | 0.69 |

| Variables | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | SE | ß | t-Value | b | SE | ß | t-Value | b | SE | ß | t-Value | |

| Constant | 3.319 | 0.144 | 23.103 *** | 3.319 | 0.144 | 23.103 *** | 2.348 | 0.266 | 8.813 *** | |||

| Sex | ||||||||||||

| Female | 0.707 | 0.062 | 0.319 | 11.431 *** | 0.707 | 0.062 | 0.319 | 11.431 *** | 0.421 | 0.062 | 0.190 | 6.754 *** |

| Education | ||||||||||||

| College/university students | 0.074 | 0.119 | 0.032 | 0.623 | 0.074 | 0.119 | 0.032 | 0.623 | 0.042 | 0.112 | 0.018 | 0.372 |

| College/university graduation | −0.022 | 0.094 | −0.010 | −0.237 | −0.022 | 0.094 | −0.010 | −0.237 | −0.052 | 0.089 | −0.024 | −0.590 |

| Graduate students or above | −0.137 | 0.145 | −0.029 | −0.941 | −0.137 | 0.145 | −0.029 | −0.941 | −0.108 | 0.136 | −0.023 | −0.794 |

| Monthly household income | ||||||||||||

| ≥790 and <2371 (low) | −0.016 | 0.076 | −0.007 | −0.212 | −0.016 | 0.076 | −0.007 | −0.212 | −0.041 | 0.072 | −0.018 | −0.576 |

| ≥2371 and <3952 (middle) | 0.049 | 0.087 | 0.017 | 0.556 | 0.049 | 0.087 | 0.017 | 0.556 | 0.032 | 0.082 | 0.011 | 0.396 |

| ≥3952 (high) | 0.085 | 0.091 | 0.029 | 0.936 | 0.085 | 0.091 | 0.029 | 0.936 | 0.094 | 0.086 | 0.031 | 1.096 |

| Occupation | ||||||||||||

| Employed | −0.001 | 0.080 | −0.001 | −0.017 | −0.001 | 0.080 | −0.001 | −0.017 | 0.048 | 0.075 | 0.022 | 0.637 |

| College/university or graduate students | −0.112 | 0.111 | −0.049 | −1.014 | −0.112 | 0.111 | −0.049 | −1.014 | −0.084 | 0.103 | −0.036 | −0.813 |

| BMI | ||||||||||||

| Normal weight | 0.113 | 0.103 | 0.051 | 1.097 | 0.113 | 0.103 | 0.051 | 1.097 | 0.122 | 0.096 | 0.055 | 1.269 |

| Overweight/obesity | 0.148 | 0.109 | 0.066 | 1.368 | 0.148 | 0.109 | 0.066 | 1.368 | 0.206 | 0.102 | 0.091 | 2.009 * |

| Meat attachment | ||||||||||||

| Hedonism | 0.024 | 0.038 | 0.021 | 0.649 | −0.008 | 0.037 | −0.007 | −0.214 | ||||

| Affinity | 0.103 | 0.033 | 0.079 | 3.146 ** | 0.134 | 0.032 | 0.103 | 4.227 *** | ||||

| Entitlement | −0.025 | 0.034 | −0.022 | −0.752 | 0.022 | 0.033 | 0.019 | 0.661 | ||||

| Dependence | −0.307 | 0.044 | −0.224 | −6.996 *** | −0.275 | 0.042 | −0.201 | −6.473 *** | ||||

| Environmental attitude | 0.420 | 0.041 | 0.262 | 10.318 *** | ||||||||

| F | 14.835 *** | 18.515 *** | 25.264 *** | |||||||||

| R2 | 0.100 | 0.160 | 0.217 | |||||||||

| Adjusted R2 | 0.093 | 0.151 | 0.208 | |||||||||

| Variables | B | SE | t | p | Variables | B | SE | t | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Affinity | 0.202 | 0.032 | 6.371 | 0.000 | Dependence | −0.280 | 0.033 | −8.491 | 0.000 |

| Environmental attitude | 0.438 | 0.041 | 10.709 | 0.000 | Environmental attitude | 0.406 | 0.040 | 10.108 | 0.000 |

| Affinity × Environmental attitude | 0.135 | 0.042 | 3.222 | 0.001 | Dependence × Environmental attitude | −0.159 | 0.046 | −3.489 | 0.000 |

| F | 23.986 (p = 0.000) | 28.325 (p = 0.000) | |||||||

| R2 | 0.187 | 0.213 | |||||||

| ΔR2 | 0.006 (F = 10.378, p = 0.001) | 0.007 (F = 12.175, p = 0.000) | |||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kim, S.-Y.; Maeng, M.H. Association of Meat Attachment with Intention to Reduce Meat Consumption Among Young Adults: Moderating Role of Environmental Attitude. Nutrients 2025, 17, 2637. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17162637

Kim S-Y, Maeng MH. Association of Meat Attachment with Intention to Reduce Meat Consumption Among Young Adults: Moderating Role of Environmental Attitude. Nutrients. 2025; 17(16):2637. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17162637

Chicago/Turabian StyleKim, So-Young, and Min Hyun Maeng. 2025. "Association of Meat Attachment with Intention to Reduce Meat Consumption Among Young Adults: Moderating Role of Environmental Attitude" Nutrients 17, no. 16: 2637. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17162637

APA StyleKim, S.-Y., & Maeng, M. H. (2025). Association of Meat Attachment with Intention to Reduce Meat Consumption Among Young Adults: Moderating Role of Environmental Attitude. Nutrients, 17(16), 2637. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17162637