Overcoming Barriers to Exclusive Breastfeeding in Lao PDR: Social Transfer Intervention Randomised Controlled Trial

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Source

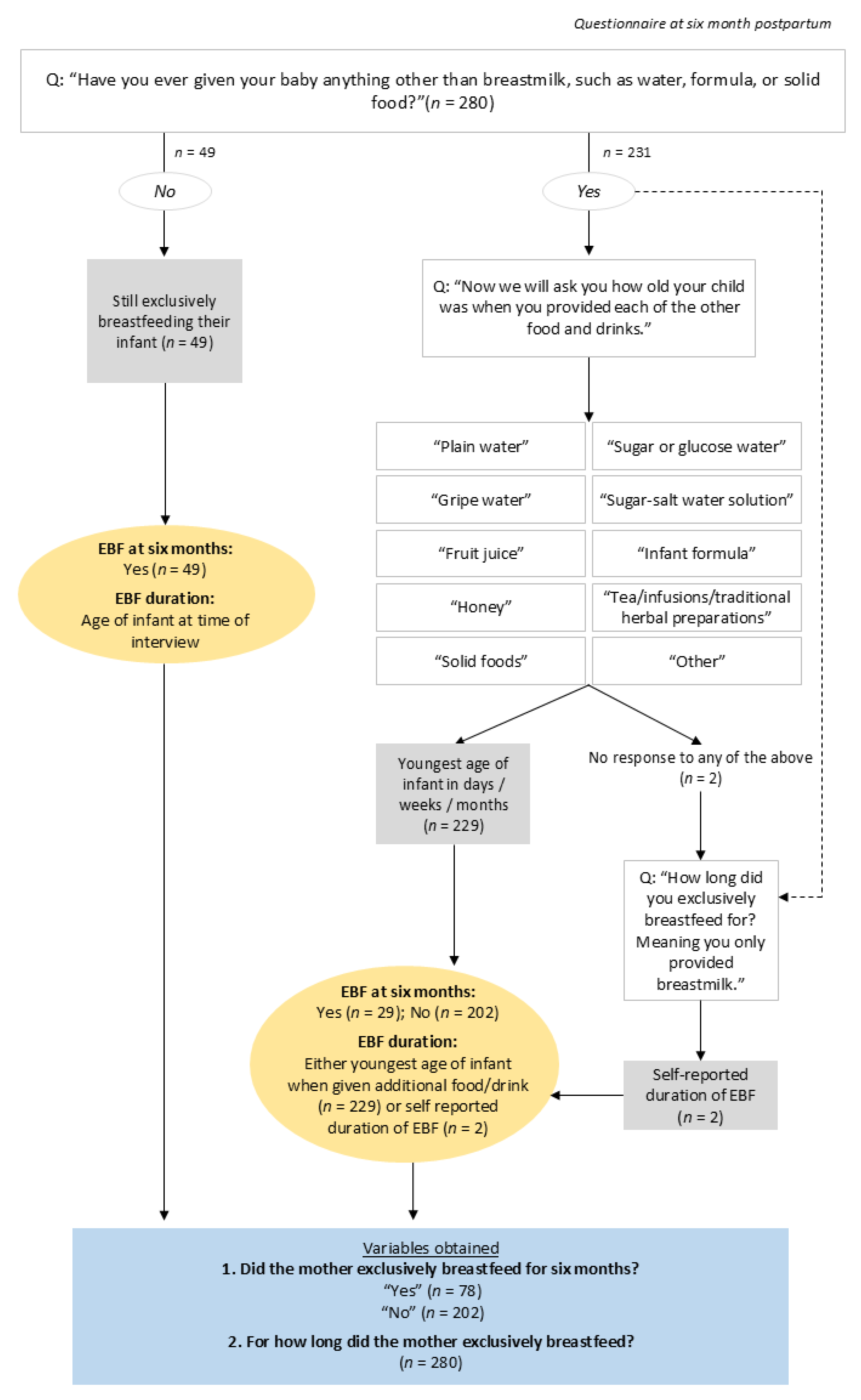

2.2. Exclusive Breastfeeding: Outcome Variable

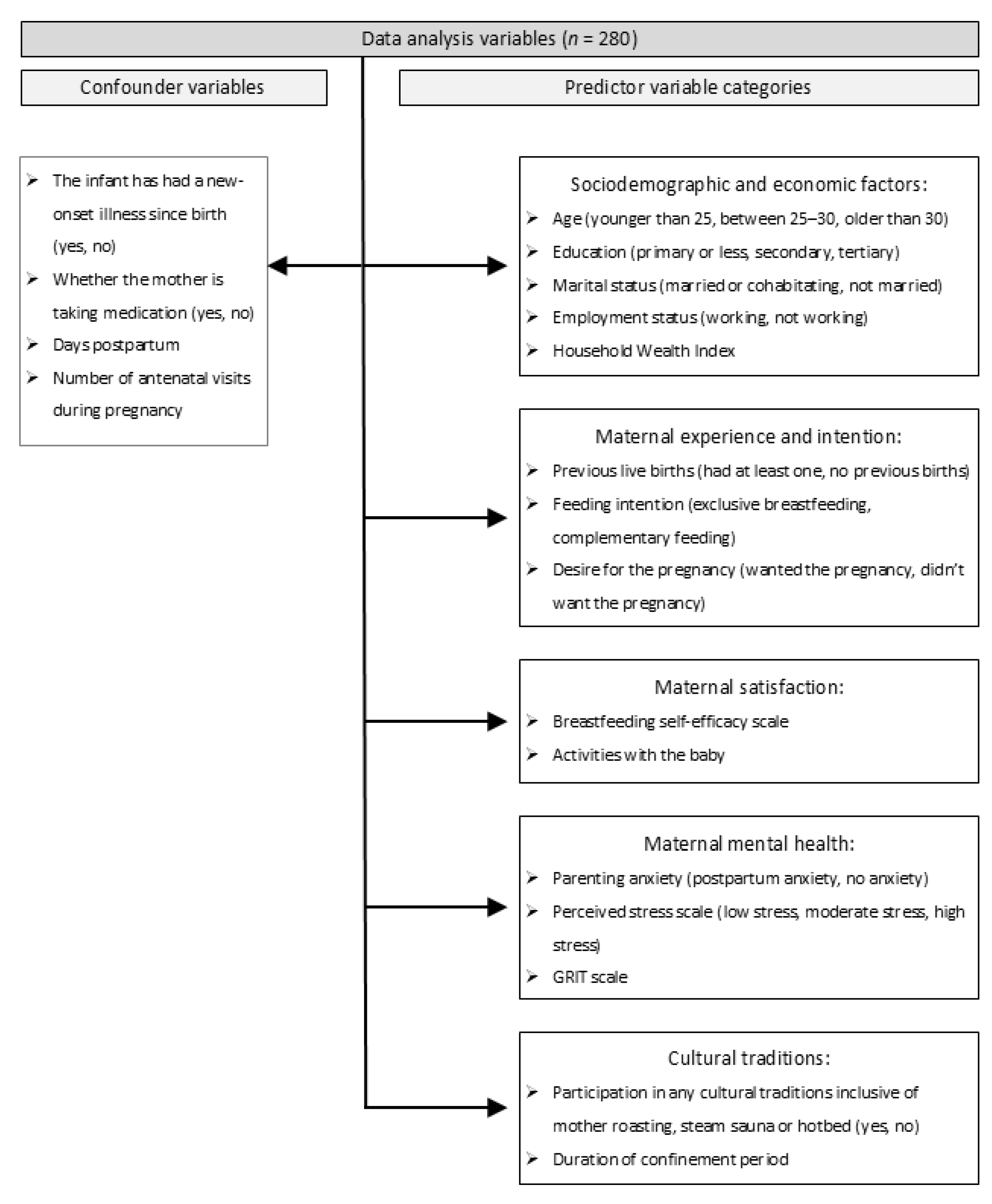

2.3. Independent Variables

2.4. Confounding Variables

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of the Participants

3.2. Association with Exclusive Breastfeeding Status at Six Months

3.3. Risk of Exclusive Breastfeeding Cessation

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CI | Confidence interval |

| EBF | Exclusive breastfeeding |

| HR | Hazard ratio |

| Lao PDR | Lao People’s Democratic Republic |

| LMIC | Low- or middle-income country |

| OR | Odds ratio |

| RCT | Randomised controlled trial |

| STEB | Social Transfers for Exclusive Breastfeeding |

| VITERBI | Vientiane Multi-Generational Birth Cohort |

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. Methodology

Appendix A.2. Unadjusted and Adjusted Logistic Regression Models

| Variable | Category | Randomised Controlled Trial Arm | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | Unconditional Social Transfer | Conditional Social Transfer | |||||||||||

| Unadjusted | Adjusted | Unadjusted | Adjusted | Unadjusted | Adjusted | ||||||||

| cOR (95% CI) | p | aOR (95% CI) | p | cOR (95% CI) | p | aOR (95% CI) | p | cOR (95% CI) | p | aOR (95% CI) | p | ||

| Age A | Younger than 25 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Between 25 and 30 | 0.69 (0.13, 3.45) | 0.65 | 0.79 (0.14, 4.10) | 0.78 | 1.11 (0.34, 3.57) | 0.87 | 1.02 (0.31, 3.35) | 0.98 | 0.70 (0.25, 1.94) | 0.49 | 0.59 (0.20, 1.73) | 0.34 | |

| Older than 30 | 1.56 (0.42, 6.56) | 0.51 | 1.69 (0.44, 7.39) | 0.46 | 0.91 (0.30, 2.81) | 0.87 | 0.82 (0.26, 2.61) | 0.74 | 0.93 (0.30, 2.88) | 0.90 | 0.75 (0.22, 2.47) | 0.64 | |

| Marital status | Not married | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Married or cohabitating | 0.87 (0.13, 17.30) | 0.90 | No adj | 1.36 (0.30, 9.61) | 0.71 | No adj | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | |||

| Maternal Education B | Primary or no education | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Secondary | 0.46 (0.10, 2.15) | 0.31 | 0.39 (0.08, 1.92) | 0.24 | 0.70 (0.22, 2.26) | 0.54 | 0.70 (0.21, 2.35) | 0.81 | 1.02 (0.36, 2.91) | 0.97 | 1.14 (0.38, 3.44) | 0.81 | |

| Tertiary | 0.83 (0.21, 3.64) | 0.79 | 0.68 (0.15, 3.17) | 0.61 | 1.54 (0.47, 5.29) | 0.48 | 1.40 (0.41, 4.96) | 0.56 | 0.83 (0.30, 2.30) | 0.71 | 0.90 (0.30, 2.76) | 0.86 | |

| Employment status at six months | Not working | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Working | 0.41 (0.06, 1.66) | 0.27 | No adj | 0.16 * (0.01, 0.88) | 0.09 | No adj | 0.34 (0.05, 1.47) | 0.19 | No adj | ||||

| Household wealth 1,C | 1.18 (0.76, 1.91) | 0.48 | 1.19 (0.76, 1.95) | 0.47 | 1.11 (0.78, 1.57) | 0.57 | 1.08 (0.75,1.54) | 0.68 | 1.13 (0.83, 1.54) | 0.44 | 1.20 (0.87, 1.69) | 0.27 | |

| Previous births C | Never given birth | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| At least one previous birth | 0.68 (0.21, 2.25) | 0.51 | 0.76 (0.23, 2.60) | 0.65 | 0.86 (0.34, 2.25) | 0.75 | 0.93 (0.36, 2.50) | 0.89 | 0.99 (0.43, 2.29) | 0.98 | 1.03 (0.44, 2.43) | 0.95 | |

| Intention to feed the baby C | Complementary feeding | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Exclusive breastfeeding | 0.67 (0.20, 2.70) | 0.55 | 0.65 (0.19, 2.61) | 0.51 | 0.43 (0.10, 1.88) | 0.24 | 0.37 (0.09, 1.67) | 0.18 | 4.63 (0.75, 89.40) | 0.16 | 3.72 (0.58, 72.80) | 0.24 | |

| Desire for the pregnancy C | Did not want the pregnancy | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Wanted the pregnancy | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 0.16 (0.01, 1.14) | 0.11 | 0.19 (0.01, 1.39) | 0.15 | |

| Breastfeeding self-efficacy 1 | 1.12 (0.87, 1.46) | 0.36 | No adj | No adj | 1.31 ** (1.06, 1.63) | 0.01 | No adj | No adj | 1.07 (0.93, 1.24) | 0.34 | No adj | No adj | |

| Caregiver activities 1 | 0.75 (0.46,1.20) | 0.24 | No adj | No adj | 0.88 (0.61, 1.23) | 0.46 | No adj | No adj | 0.81 (0.57, 1.15) | 0.25 | No adj | No adj | |

| Postpartum Anxiety C | Has anxiety | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| No postpartum anxiety | 1.05 (0.30, 3.35) | 0.93 | 0.96 (0.26, 3.18) | 0.95 | 2.08 (0.79, 5.97) | 0.15 | 2.04 (0.77, 5.90) | 0.17 | 0.60 (0.26, 1.39) | 0.24 | 0.59 (0.25, 1.39) | 0.23 | |

| Perceived stress C | Low stress | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Moderate stress | 1.26 (0.40, 4.43) | 0.70 | 1.17 (0.36, 4.16) | 0.80 | 1.14 (0.45, 2.98) | 0.78 | 1.24 (0.48, 3.29) | 0.66 | 1.03 (0.43, 2.55) | 0.94 | 1.14 (0.45, 2.99) | 0.79 | |

| Grit scale 1 | 1.51 (0.27, 8.85) | 0.64 | No adj | 3.69 * (1.00, 15.00) | 0.06 | No adj | 0.86 (0.31, 2.35) | 0.78 | No adj | ||||

| Participation in at least one of these: hotbed, mother roasting or steam sauna C | Did not participate | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Participated in at least one | 1.23 (0.19, 24.00) | 0.85 | 1.33 (0.21, 26.00) | 0.80 | 0.72 (0.17, 3.65) | 0.66 | 0.76 (0.18, 3.90) | 0.72 | 0.39 (0.08, 1.69) | 0.22 | 0.39 (0.08, 1.69) | 0.22 | |

| Confinement duration 1,D | 1.02 (0.98, 1.06) | 0.25 | 1.02 (0.98, 1.05) | 0.42 | 1.01 (0.99, 1.04) | 0.33 | 1.02 (0.46, 5.15) | 0.20 | 0.98 * (0.96, 1.00) | 0.09 | 0.98 (0.96, 1.01) | 0.16 | |

Appendix A.3. Unadjusted and Adjusted Cox Proportional Hazards Model

| Variable | Category | Randomised Controlled Trial Arm | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | Unconditional Social Transfer | Conditional Social Transfer | |||||||||||

| Unadjusted | Adjusted | Unadjusted | Adjusted | Unadjusted | Adjusted | ||||||||

| cHR (95% CI) | p | aHR (95% CI) | p | cHR (95% CI) | p | aHR (95% CI) | p | cHR (95% CI) | p | aHR (95% CI) | p | ||

| Age A | Younger than 25 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Between 25 and 30 | 0.96 (0.57, 1.59) | 0.86 | 0.91 (0.54, 1.53) | 0.73 | 1.03 (0.61, 1.75) | 0.09 | 1.11 (0.64, 1.90) | 0.72 | 1.28 (0.77, 2.14) | 0.35 | 1.36 (0.81, 2.28) | 0.25 | |

| Older than 30 | 0.80 (0.49, 1.32) | 0.39 | 0.77 (0.46, 1.28) | 0.31 | 0.98 (0.60, 1.60) | 0.93 | 1.02 (0.60, 1.73) | 0.94 | 1.27 (0.72, 2.25) | 0.41 | 1.28 (0.72, 2.28) | 0.40 | |

| Marital status B | Not married | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Married or cohabitating | 2.12 (0.85, 5.27) | 0.11 | 2.11 (0.85, 5.24) | 0.11 | 0.87 (0.43, 1.73) | 0.69 | 1.06 (0.51, 2.21) | 0.88 | 1.60 (0.65, 3.96) | 0.31 | 1.60 (0.65, 3.95) | 0.31 | |

| Maternal Education A | Primary or no education | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Secondary | 1.40 (0.82, 2.41) | 0.22 | 1.46 (0.83, 2.54) | 0.19 | 1.39 (0.84, 2.29) | 0.20 | 1.43 (0.85, 2.40) | 0.18 | 0.89 (0.52, 1.50) | 0.65 | 1.00 (0.57, 1.75) | 0.99 | |

| Tertiary | 0.95 (0.55, 1.65) | 0.86 | 0.98 (0.55, 1.77) | 0.96 | 0.98 (0.56, 1.71) | 0.94 | 1.04 (0.59, 1.84) | 0.88 | 1.09 (0.66, 1.80) | 0.73 | 1.17 (0.69, 1.97) | 0.57 | |

| Employment status at six months | Not working | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Working | 1.07 (0.66, 1.73) | 0.78 | No adj | 2.19 ** (1.26, 3.95) | 0.01 | No adj | 1.40 (0.72, 2.73) | 0.32 | No adj | ||||

| Household wealth 1,A | 0.96 (0.82, 1.11) | 0.56 | 0.95 (0.81, 1.13) | 0.58 | 0.99 (0.85, 1.16) | 0.92 | 1.05 (0.89, 1.24) | 0.53 | 0.94 (0.83, 1.11) | 0.62 | 1.00 (0.85, 1.17) | 0.97 | |

| Previous births C | Never given birth | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| At least one previous birth | 1.16 (0.76, 1.78) | 0.49 | 1.15 (0.74, 1.77) | 0.54 | 1.11 (0.73, 1.70) | 0.62 | 1.28 (0.82, 2.01) | 0.28 | 1.18 (0.78, 1.79) | 0.44 | 1.16 (0.76, 1.76) | 0.49 | |

| Intention to feed the baby | Complementary feeding | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Exclusive breastfeeding | 0.88 (0.54, 1.44) | 0.59 | No adj | 1.16 (0.58, 2.31) | 0.67 | No adj | 0.50 * (0.23, 1.10) | 0.08 | No adj | ||||

| Desire for the pregnancy B | Did not want the pregnancy | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Wanted the pregnancy | 1.04 (0.38, 2.83) | 0.95 | 1.03 (0.38, 2.82) | 0.95 | 0.43 * (0.20, 0.95) | 0.04 | 0.42 ** (0.19, 0.92) | 0.03 | 1.28 (0.52, 3.16) | 0.59 | 1.27 (0.51, 3.15) | 0.61 | |

| Breastfeeding self-efficacy 1 | 0.94 (0.87, 1.02) | 0.13 | No adj | 0.86 ** (0.78, 0.96) | 0.00 | No adj | 0.99 (0.92, 1.06) | 0.72 | No adj | ||||

| Caregiver activities 1 | 1.10 (0.93, 1.30) | 0.25 | No adj | 1.09 (0.96, 1.25) | 0.19 | No adj | 1.17 * (0.98, 1.40) | 0.08 | No adj | ||||

| Postpartum Anxiety D | Has anxiety | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| No postpartum anxiety | 0.88 (0.57, 1.36) | 0.57 | 0.92 (0.59, 1.42) | 0.71 | 1.00 (0.66, 1.52) | 0.99 | 1.01 (0.65, 1.59) | 0.95 | 1.40 (0.92, 2.12) | 0.12 | 1.42 (0.93, 2.16) | 0.11 | |

| Perceived stress E | Low stress | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Moderate stress | 0.87 (0.58, 1.32) | 0.52 | 0.92 (0.60, 1.42) | 0.71 | 1.09 (0.72) | 0.67 | 1.06 (0.69, 1.61) | 0.80 | 0.86 (0.56, 1.34) | 0.52 | 0.81 (0.52, 1.28) | 0.38 | |

| Grit scale 1,C | 0.73 (0.38, 1.43) | 0.36 | 0.66 (0.33, 1.31) | 0.23 | 0.66 (0.38, 1.16) | 0.15 | 0.62 (0.34, 1.14) | 0.13 | 1.05 (0.64, 1.72) | 0.84 | 1.07 (0.65, 1.75) | 0.79 | |

| Participation at least one of: hotbed, mother roasting or steam sauna E | Did not participate | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Participated in at least one | 0.93( 0.45, 1.92) | 0.85 | 0.93 (0.45, 1.92) | 0.84 | 1.08 (0.54, 2.16) | 0.82 | 1.05 (0.52, 2.10) | 0.89 | 1.45 (0.70, 2.99) | 0.32 | 1.33 (0.61, 2.93) | 0.48 | |

| Confinement duration 1 | 0.99 * (0.98, 1.00) | 0.05 | No Adj | 0.99 (0.98, 1.00) | 0.21 | No Adj | 1.00 (0.99, 1.01) | 0.44 | No Adj | ||||

References

- Horta, B.L.; Loret de Mola, C.; Victora, C.G. Long-term consequences of breastfeeding on cholesterol, obesity, systolic blood pressure and type 2 diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Paediatr. 2015, 104, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prell, C.; Koletzko, B. Breastfeeding and Complementary Feeding. Dtsch. Arztebl. Int. 2016, 113, 435–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Elsen, L.W.J.; Garssen, J.; Burcelin, R.; Verhasselt, V. Shaping the Gut Microbiota by Breastfeeding: The Gateway to Allergy Prevention? Front. Pediatr. 2019, 7, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edmond, K.M.; Zandoh, C.; Quigley, M.A.; Amenga-Etego, S.; Owusu-Agyei, S.; Kirkwood, B.R. Delayed Breastfeeding Initiation Increases Risk of Neonatal Mortality. Pediatrics 2006, 117, e380–e386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frank, N.M.; Lynch, K.F.; Uusitalo, U.; Yang, J.; Lönnrot, M.; Virtanen, S.M.; Hyöty, H.; Norris, J.M.; the TEDDY Study Group. The relationship between breastfeeding and reported respiratory and gastrointestinal infection rates in young children. BMC Pediatr. 2019, 19, 339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kramer, M.S.; Aboud, F.; Mironova, E.; Vanilovich, I.; Platt, R.W.; Matush, L.; Igumnov, S.; Fombonne, E.; Bogdanovich, N.; Ducruet, T.; et al. Breastfeeding and child cognitive development: New evidence from a large randomized trial. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2008, 65, 578–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rito, A.I.; Buoncristiano, M.; Spinelli, A.; Salanave, B.; Kunešová, M.; Hejgaard, T.; García Solano, M.; Fijałkowska, A.; Sturua, L.; Hyska, J.; et al. Association between Characteristics at Birth, Breastfeeding and Obesity in 22 Countries: The WHO European Childhood Obesity Surveillance Initiative—COSI 2015/2017. Obes. Facts. 2019, 12, 226–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horta, B.L.; de Lima, N.P. Breastfeeding and Type 2 Diabetes: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Curr. Diab. Rep. 2019, 19, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tschiderer, L.; Seekircher, L.; Kunutsor, S.K.; Peters, S.A.E.; O’kEeffe, L.M.; Willeit, P. Breastfeeding Is Associated With a Reduced Maternal Cardiovascular Risk: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Involving Data From 8 Studies and 1 192 700 Parous Women. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2022, 11, e022746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, R.; Sinha, B.; Sankar, M.J.; Taneja, S.; Bhandari, N.; Rollins, N.; Bahl, R.; Martines, J. Breastfeeding and maternal health outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Paediatr. 2015, 104, 96–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pope, C.J.; Mazmanian, D. Breastfeeding and Postpartum Depression: An Overview and Methodological Recommendations for Future Research. Depress. Res. Treat. 2016, 2016, 4765310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNICEF; WHO. Implementation Guidance: Protecting, Promoting and Supporting Breastfeeding in Facilities Providing Maternity and Newborn Services: The Revised Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative; UNICEF, WHO: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organisation. Infant and Young Child Feeding; World Health Organisation: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021; Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/infant-and-young-child-feeding (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- UNICEF Breastfeeding. 2022. Available online: https://data.unicef.org/topic/nutrition/breastfeeding/#data (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- Alive; Thrive. The Cost of Not Breastfeeding in Southeast Asia. 2022. Available online: https://www.aliveandthrive.org/sites/default/files/attachments/Regional-Cost-of-Not-Breastfeeding_ASEAN_V7.pdf (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- Alive; Thrive. The Cost of Not Breastfeeding: Laos. 2022. Available online: https://www.aliveandthrive.org/sites/default/files/the_cost_of_not_breastfeeding_2022_laos_v4.pdf (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- Huang, Y.; Ouyang, Y.-Q.; Redding, S.R. Previous breastfeeding experience and its influence on breastfeeding outcomes in subsequent births: A systematic review. Women Birth 2019, 32, 303–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shiraishi, M.; Matsuzaki, M.; Kurihara, S.; Iwamoto, M.; Shimada, M. Post-breastfeeding stress response and breastfeeding self-efficacy as modifiable predictors of exclusive breastfeeding at 3 months postpartum: A prospective cohort study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2020, 20, 730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sriraman, N.K.; Kellams, A. Breastfeeding: What are the Barriers? Why Women Struggle to Achieve Their Goals. J. Women’s Health 2016, 25, 714–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Awaliyah, S.N.; Rachmawati, I.N.; Rahmah, H. Breastfeeding self-efficacy as a dominant factor affecting maternal breastfeeding satisfaction. BMC Nurs. 2019, 18, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lio, R.M.S.; Maugeri, A.; La Rosa, M.C.; Cianci, A.; Panella, M.; Giunta, G.; Agodi, A.; Barchitta, M. The Impact of Socio-Demographic Factors on Breastfeeding: Findings from the “Mamma & Bambino” Cohort. Medicina 2021, 57, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AAlzaheb, R. A Review of the Factors Associated With the Timely Initiation of Breastfeeding and Exclusive Breastfeeding in the Middle East. Clin. Med. Insights: Pediatr. 2017, 11, 1179556517748912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apostolakis-Kyrus, K.; Valentine, C.; DeFranco, E. Factors Associated with Breastfeeding Initiation in Adolescent Mothers. J. Pediatr. 2013, 163, 1489–1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balogun, O.O.; Dagvadorj, A.; Anigo, K.M.; Ota, E.; Sasaki, S. Factors influencing breastfeeding exclusivity during the first 6 months of life in developing countries: A quantitative and qualitative systematic review. Matern. Child. Nutr. 2015, 11, 433–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, P.C.; Angdembe, M.R.; Das, S.K.; Ahmed, S.; Faruque, A.S.G.; Ahmed, T. Prevalence of exclusive breastfeeding and associated factors among mothers in rural Bangladesh: A cross-sectional study. Int. Breastfeed. J. 2014, 9, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Titaley, C.R.; Loh, P.C.; Prasetyo, S.; Ariawan, I.; Shankar, A.H. Socio-economic factors and use of maternal health services are associated with delayed initiation and non-exclusive breastfeeding in Indonesia: Secondary analysis of Indonesia Demographic and Health Surveys 2002/2003 and 2007. Asia Pac. J. Clin. Nutr. 2014, 23, 91–104. [Google Scholar]

- Barennes, H.; Simmala, C.; Odermatt, P.; Thaybouavone, T.; Vallee, J.; Martinez-Aussel, B.; Newton, P.N.; Strobel, M. Postpartum traditions and nutrition practices among urban Lao women and their infants in Vientiane, Lao PDR. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2009, 63, 323–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, T.J.; Tan, X.; Arnold, C.D.; Sitthideth, D.; Kounnavong, S.; Hess, S.Y. Traditional prenatal and postpartum food restrictions among women in northern Lao PDR. Matern. Child. Nutr. 2021, 18, e13273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Withers, M.; Kharazmi, N.; Lim, E. Traditional beliefs and practices in pregnancy, childbirth and postpartum: A review of the evidence from Asian countries. Midwifery 2018, 56, 158–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Boer, H.J.; Lamxay, V.; Björk, L. Steam sauna and mother roasting in Lao PDR: Practices and chemical constituents of essential oils of plant species used in postpartum recovery. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2011, 11, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amorim, M.; Hobby, E.; Zamora-Kapoor, A.; Perham-Hester, K.A.; Cowan, S.K. The heterogeneous associations of universal cash-payouts with breastfeeding initiation and continuation. SSM Popul. Health 2023, 22, 101362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Relton, C.; Strong, M.; Thomas, K.J.; Whelan, B.; Walters, S.J.; Burrows, J.; Scott, E.; Viksveen, P.; Johnson, M.; Baston, H.; et al. Effect of Financial Incentives on Breastfeeding: A Cluster Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Pediatr. 2018, 172, e174523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuthill, E.L.; Maltby, A.E.; Odhiambo, B.C.; Hoffmann, T.J.; Nyaura, M.; Shikari, R.; Cohen, C.R.; Weiser, S.D. “It has changed my life”: Unconditional cash transfers and personalized infant feeding support—A feasibility intervention trial among women living with HIV in western Kenya. Int. Breastfeed. J. 2023, 18, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallenborn, J.T.; Sonephet, S.; Sayasone, S.; Siengsounthone, L.; Kounnavong, S.; Fink, G. Conditional and Unconditional Social Transfers, Early-Life Nutrition, and Child Growth. JAMA Pediatr. 2025, 179, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonephet, S.; Kounnavong, S.; Zinsstag, L.; Vonaesch, P.; Sayasone, S.; Siengsounthone, L.; Odermatt, P.; Fink, G.; Wallenborn, J.T. Social Transfers for Exclusive Breastfeeding (STEB) Intervention in Lao People’s Democratic Republic: Protocol for a Randomized Controlled Trial. JMIR Res. Protoc. 2024, 13, e54768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallenborn, J.T.; Sinantha-Hu, M.; Ouipoulikoune, V.; Kounnavong, S.; Siengsounthone, L.; Probst-Hensch, N.; Odermatt, P.; Sayasone, S.; Fink, G. Vientiane Multigenerational Birth Cohort Project in Lao People’s Democratic Republic: Protocol for Establishing a Longitudinal Multigenerational Birth Cohort to Promote Population Health. JMIR Res. Protoc. 2024, 13, e59545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shea Oscar Rutstein Johnson, K. The DHS Wealth Index; The Demographic Health Surveys Program: Rockville, MD, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Dennis, C. The Breastfeeding Self-Efficacy Scale: Psychometric Assessment of the Short Form. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Neonatal Nurs. 2003, 32, 734–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quail, A.; Williams, J.; McCrory, C.; Murray, A.; Thornton, M. National Longitudinal Study of Children in Ireland (NLSCI); University of Dublin, Trinity College, The Economic and Social Research Institute: Dublin, Ireland, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, S.; Kamarck, T.; Mermelstein, R. A Global Measure of Perceived Stress. J. Health Soc. Behav. 1983, 24, 385–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duckworth, A.L.; Quinn, P.D. Development and Validation of the Short Grit Scale (Grit–S). J. Pers. Assess. 2009, 91, 166–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silverio, S.A.; Davies, S.M.; Christiansen, P.; Aparicio-García, M.E.; Bramante, A.; Chen, P.; Costas-Ramón, N.; de Weerth, C.; Della Vedova, A.M.; Gil, L.I.; et al. A validation of the Postpartum Specific Anxiety Scale 12-item research short-form for use during global crises with five translations. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2021, 21, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dao-Tran, T.-H.; Anderson, D.; Seib, C. The Vietnamese version of the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS-10): Translation equivalence and psychometric properties among older women. BMC Psychiatry 2017, 17, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Services, N.H.D.o.A. Perceived Stress Scale. 2024. Available online: https://www.das.nh.gov/wellness/docs/percieved%20stress%20scale.pdf (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- Fuller, J. The Confounding Question of Confounding Causes in Randomized Trials. Br. J. Philos. Sci. 2018, 70, 901–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gianni, M.L.; Bettinelli, M.E.; Manfra, P.; Sorrentino, G.; Bezze, E.; Plevani, L.; Cavallaro, G.; Raffaeli, G.; Crippa, B.L.; Colombo, L.; et al. Breastfeeding Difficulties and Risk for Early Breastfeeding Cessation. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClatchey, A.K.; Shield, A.; Cheong, L.H.; Ferguson, S.L.; Cooper, G.M.; Kyle, G.J. Why does the need for medication become a barrier to breastfeeding? A narrative review. Women Birth 2018, 31, 362–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, H.; Yang, Y.; Yin, X.; Li, J.; Fang, J.; Wang, X. Determinants of exclusive breastfeeding for the first six months in China: A cross-sectional study. Int. Breastfeed. J. 2021, 16, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tariku, A.; Alemu, K.; Gizaw, Z.; Muchie, K.F.; Derso, T.; Abebe, S.M.; Yitayal, M.; Fekadu, A.; Ayele, T.A.; Alemayehu, G.A.; et al. Mothers’ education and ANC visit improved exclusive breastfeeding in Dabat Health and Demographic Surveillance System Site, northwest Ethiopia. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0179056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-De-Mariscal, E.; Guerrero, V.; Sneider, A.; Jayatilaka, H.; Phillip, J.M.; Wirtz, D.; Muñoz-Barrutia, A. Use of the p-values as a size-dependent function to address practical differences when analyzing large datasets. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 20942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wickham, H. Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis; Springer-Verlag: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Wickham, H.; Averick, M.; Bryan, J.; Chang, W.; McGowan, L.D.A.; François, R.; Grolemund, G.; Hayes, A.; Henry, L.; Hester, J.; et al. Welcome to the Tidyverse. J. Open Source Softw. 2019, 4, 1686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassambara, A.; Kosinski, M.; Biecek, P.; Fabian, S. Survminer Package. 2024. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/survminer/index.html (accessed on 1 June 2025). [CrossRef]

- Therneau, T.M.; A Package for Survival Analysis in R. Survival Package. 2024. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=survival (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- Laksono, A.D.; Wulandari, R.D.; Ibad, M.; Kusrini, I. The effects of mother’s education on achieving exclusive breastfeeding in Indonesia. BMC Public. Health 2021, 21, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ngandu, C.B.; Momberg, D.; Magan, A.; Chola, L.; Norris, S.A.; Said-Mohamed, R. The association between household socio-economic status, maternal socio-demographic characteristics and adverse birth and infant growth outcomes in sub-Saharan Africa: A systematic review. J. Dev. Orig. Health Dis. 2019, 11, 317–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Senarath, U.; Dibley, M.J.; Agho, K.E. Factors Associated With Nonexclusive Breastfeeding in 5 East and Southeast Asian Countries: A Multilevel Analysis. J. Hum. Lact. 2010, 26, 248–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wako, W.G.; Wayessa, Z.; Fikrie, A. Effects of maternal education on early initiation and exclusive breastfeeding practices in sub-Saharan Africa: A secondary analysis of Demographic and Health Surveys from 2015 to 2019. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e054302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.; Islam, A.; Kamarul, T.; Hossain, G. Exclusive breastfeeding practice during first six months of an infant’s life in Bangladesh: A country based cross-sectional study. BMC Pediatr. 2018, 18, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neves, P.A.R.; Barros, A.J.D.; Gatica-Domínguez, G.; Vaz, J.S.; Baker, P.; Lutter, C.K. Maternal education and equity in breastfeeding: Trends and patterns in 81 low- and middle-income countries between 2000 and 2019. Int. J. Equity Health 2021, 20, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, K.L. Factors associated with exclusive breastfeeding among infants under six months of age in peninsular malaysia. Int. Breastfeed. J. 2011, 6, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, D.L.; Fong, D.Y.T.; Tarrant, M. Factors Associated with Breastfeeding Duration and Exclusivity in Mothers Returning to Paid Employment Postpartum. Matern. Child. Health J. 2014, 19, 990–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chekol, D.A.; Biks, G.A.; Gelaw, Y.A.; Melsew, Y.A. Exclusive breastfeeding and mothers’ employment status in Gondar town, Northwest Ethiopia: A comparative cross-sectional study. Int. Breastfeed. J. 2017, 12, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, N.M.; Lee, J.E.; Bai, Y.; Van Achterberg, T.; Hyun, T. Breastfeeding Initiation and Continuation by Employment Status among Korean Women. J. Korean Acad. Nurs. 2015, 45, 306–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lesorogol, C.; Bond, C.; Dulience, S.J.L.; Iannotti, L. Economic determinants of breastfeeding in Haiti: The effects of poverty, food insecurity, and employment on exclusive breastfeeding in an urban population. Matern. Child. Nutr. 2017, 14, e12524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Roza, J.G.; Fong, M.K.; Ang, B.L.; Sadon, R.B.; Koh, E.Y.L.; Teo, S.S.H. Exclusive breastfeeding, breastfeeding self-efficacy and perception of milk supply among mothers in Singapore: A longitudinal study. Midwifery 2019, 79, 102532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, H.S.L.; Fong, D.Y.T.; Lok, K.Y.W.; Tarrant, M. The Association Between Breastfeeding Self-Efficacy and Mode of Infant Feeding. Breastfeed. Med. 2022, 17, 687–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otsuka, K.; Taguri, M.; Dennis, C.L.; Wakutani, K.; Awano, M.; Yamaguchi, T.; Jimba, M. Effectiveness of a breastfeeding self-efficacy intervention: Do hospital practices make a difference? Matern. Child. Health J. 2014, 18, 296–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azizi, E.; Maleki, A.; Mazloomzadeh, S.; Pirzeh, R. Effect of Stress Management Counseling on Self-Efficacy and Continuity of Exclusive Breastfeeding. Breastfeed. Med. 2020, 15, 501–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chipojola, R.; Chiu, H.-Y.; Huda, M.H.; Lin, Y.-M.; Kuo, S.-Y. Effectiveness of theory-based educational interventions on breastfeeding self-efficacy and exclusive breastfeeding: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2020, 109, 103675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngo, L.T.H.; Chou, H.-F.; Gau, M.-L.; Liu, C.-Y. Breastfeeding self-efficacy and related factors in postpartum Vietnamese women. Midwifery 2019, 70, 84–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shariat, M.; Abedinia, N.; Noorbala, A.A.; Zebardast, J.; Moradi, S.; Shahmohammadian, N.; Karimi, A.; Abbasi, M. Breastfeeding Self-Efficacy as a Predictor of Exclusive Breastfeeding: A Clinical Trial. Iran. J. Neonatol. 2018, 9, 26–34. [Google Scholar]

- Hmone, M.P.; Li, M.; Agho, K.; Alam, A.; Dibley, M.J. Factors associated with intention to exclusive breastfeed in central women’s hospital, Yangon, Myanmar. Int. Breastfeed. J. 2017, 12, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linares, A.M.; Rayens, M.K.; Gomez, M.L.; Gokun, Y.; Dignan, M.B. Intention to Breastfeed as a Predictor of Initiation of Exclusive Breastfeeding in Hispanic Women. J. Immigr. Minor. Health 2014, 17, 1192–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tengku Ismail, T.A.; Wan Muda, W.A.; Bakar, M.I. The extended Theory of Planned Behavior in explaining exclusive breastfeeding intention and behavior among women in Kelantan, Malaysia. Nutr. Res. Pract. 2016, 10, 49–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Ip, W.-Y.; Gao, L.-L. Maternal intention to exclusively breast feed among mainland Chinese mothers: A cross-sectional study. Midwifery 2018, 57, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raissian, K.M.; Su, J.H. The best of intentions: Prenatal breastfeeding intentions and infant health. SSM Popul. Health 2018, 5, 86–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doan, D.T.T.; Binns, C.; Lee, A.; Zhao, Y.; Pham, M.N.; Dinh, H.T.P.; Nguyen, C.C.; Bui, H.T.T.; Doherty, T. Factors associated with intention to breastfeed in Vietnamese mothers: A cross-sectional study. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0279691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, L.F.; Cortellazzi, K.L.; de Melo, L.S.A.; da Silva, S.R.C.; Rosell, F.L.; Júnior, A.V.; Tagliaferro, E.P.d.S. Exclusive breastfeeding intention among pregnant women and associated variables: A cross-sectional study in a Brazilian community. Rev. Paul. De. Pediatr. 2024, 42, e2022192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, K.Y.; Page, A.; Arora, A.; Ogbo, F.A. Trends and determinants of early initiation of breastfeeding and exclusive breastfeeding in Ethiopia from 2000 to 2016. Int. Breastfeed. J. 2019, 14, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keddem, S.; Frasso, R.; Dichter, M.; Hanlon, A. The Association Between Pregnancy Intention and Breastfeeding. J. Hum. Lact. 2017, 34, 97–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stalcup, A.M. Women’s Intentions for Pregnancy and Breastfeeding Impact Breastfeeding Outcomes, Implications & Opportunities [16F]. Obstet. Gynecol. 2018, 131, 66S. [Google Scholar]

- Li, R.; Ingol, T.T.; Smith, K.; Oza-Frank, R.; Keim, S.A. Reliability of Maternal Recall of Feeding at the Breast and Breast Milk Expression 6 Years After Delivery. Breastfeed. Med. 2020, 15, 224–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seabrook, J.A.; Cahill, N. How Many Participants Are Needed? Strategies for Calculating Sample Size in Nutrition Research. Can. J. Diet. Pract. Res. 2025, 86, 479–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaafsma, H.; Laasanen, H.; Twynstra, J.; Seabrook, J.A. A Review of Statistical Reporting in Dietetics Research (2010-2019): How is a Canadian Journal Doing? Can. J. Diet. Pract. Res. 2021, 82, 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- AParker, R.; Weir, C.J. Non-adjustment for multiple testing in multi-arm trials of distinct treatments: Rationale and justification. Clin. Trials 2020, 17, 562–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Characteristic | Overall (n = 298) | Randomised Controlled Trial Arm | p-Value 1 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control (n = 101) | Unconditional Social Transfer (n = 97) | Conditional Social Transfer (n = 100) | |||

| n (%) | |||||

| Maternal age (years) | 0.12 | ||||

| Younger than 25 | 92 (31.2%) | 32 (32.0%) | 33 (34.4%) | 27 (27.3%) | |

| Between 25 and 30 | 104 (35.3%) | 32 (32.0%) | 27 (28.1%) | 45 (45.5%) | |

| Older than 30 | 99 (33.6%) | 36 (36.0%) | 36 (37.5%) | 27 (27.3%) | |

| Marital status | 0.50 | ||||

| Married or cohabitating | 274 (92.9%) | 93 (93.0%) | 87 (90.6%) | 94 (94.9%) | |

| Not married | 6 (7.1%) | 8 (7.0%) | 10 (9.4%) | 6 (5.1%) | |

| Maternal education | 0.20 | ||||

| Primary or no education | 76 (25.8%) | 21 (21.0%) | 25 (26.0%) | 30 (30.0%) | |

| Secondary | 119 (40.3%) | 43 (43.0%) | 44 (45.8%) | 32 (32.3%) | |

| Tertiary | 100 (33.9%) | 36 (36.0%) | 27 (28.1%) | 37 (37.4%) | |

| District in Vientiane | 0.40 | ||||

| Chanthabuly | 31 (10.9%) | 9 (9.2%) | 11 (12.1%) | 11 (11.5%) | |

| Pakngum | 67 (23.5%) | 17 (17.3%) | 23 (25.3%) | 27 (28.1%) | |

| Sangthong | 64 (22.5%) | 23 (23.5%) | 24 (26.4%) | 17 (17.7%) | |

| Sikhottabong | 123 (43.2%) | 49 (50.0%) | 33 (36.3%) | 41 (42.7%) | |

| Employment status at one month | 0.20 | ||||

| Working | 8 (2.8%) | 1 (1.0%) | 2 (2.2%) | 5 (5.4%) | |

| Not working | 274 (97.2%) | 96 (99.0%) | 90 (97.8%) | 88 (94.6%) | |

| Household wealth index | 0.02 | ||||

| 1st quartile | 63 (21.1%) | 15 (14.9%) | 27 (27.8%) | 21 (21.0%) | |

| 2nd quartile | 57 (19.1%) | 12 (11.9%) | 25 (25.8%) | 20 (20.0%) | |

| 3rd quartile | 59 (19.8%) | 28 (27.7%) | 12 (12%) | 19 (19.0%) | |

| 4th quartile | 80 (26.8%) | 29 (28.7%) | 25 (26%) | 26 (26.0%) | |

| 5th quartile | 39 (13.1%) | 17 (16.8%) | 8 (8.2%) | 14 (14.0%) | |

| Previous births | 0.50 | ||||

| No previous births | 115 (39.1%) | 35 (35.0%) | 37 (38.9%) | 43 (43.4%) | |

| At least one previous birth | 179 (60.9%) | 65 (65.0%) | 58 (61.1%) | 56 (56.6%) | |

| Intention to feed the baby | 0.01 | ||||

| Exclusive breastfeeding | 254 (86.1%) | 78 (78.0%) | 85 (88.5%) | 91 (91.9%) | |

| Complementary feeding | 41 (13.9%) | 22 (22.0%) | 11 (11.5%) | 8 (8.1%) | |

| Desire for the pregnancy | 0.60 | ||||

| Wanted the pregnancy | 279 (94.6%) | 96 (96.0%) | 89 (92.7%) | 94 (94.9%) | |

| Did not want the pregnancy | 16 (5.4%) | 4 (4%) | 7 (7.3%) | 5 (5.1%) | |

| Variable | Category | Randomised Controlled Trial Arm | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | Unconditional Social Transfer | Conditional Social Transfer | |||||

| OR (95% CI) | p | OR (95% CI) | p | OR (95% CI) | p | ||

| Age | Younger than 25 | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Between 25 and 30 | 0.61 (0.09, 3.91) | 0.60 | 1.86 (0.41, 9.38) | 0.43 | 0.30 (0.06, 1.36) | 0.13 | |

| Older than 30 | 2.02 (0.36, 12.80) | 0.43 | 1.11 (0.26, 5.14) | 0.89 | 0.48 (0.09, 2.62) | 0.40 | |

| Marital status | Not married | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Married or cohabitating | N/A | N/A | 1.15 (0.11, 15.60) | 0.91 | N/A | N/A | |

| Maternal education | Primary or no education | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Secondary | 0.20 * (0.03, 1.30) | 0.09 | 0.72 (0.16, 3.27) | 0.66 | 1.03 (0.19, 5.53) | 0.97 | |

| Tertiary | 0.33 (0.04, 2.51) | 0.29 | 1.64 (0.30, 9.14) | 0.56 | 0.85 (0.15, 4.83) | 0.85 | |

| Employment status at six months | Not working | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Working | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 0.20 (0.01, 1.65) | 0.18 | |

| Household wealth 1 | 1.25 (0.67, 2.52) | 0.51 | 1.08 (0.66, 1.77) | 0.76 | 1.54 (0.86, 2.96) | 0.16 | |

| Previous births | Never given birth | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| At least one previous birth | 0.49 (0.11, 2.17) | 0.34 | 1.20 (0.29, 5.27) | 0.80 | 0.66 (0.19, 2.17) | 0.49 | |

| Intention to feed the baby | Complementary feeding | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Exclusive breastfeeding | 0.45 (0.08, 2.52) | 0.35 | 0.48 (0.09, 2.64) | 0.39 | N/A | N/A | |

| Desire for the pregnancy | Did not want the pregnancy | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Wanted the pregnancy | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 0.16(0.01, 1.80) | 0.17 | |

| Breastfeeding self-efficacy 1 | 1.21 (0.86, 1.82) | 0.30 | 1.39 ** (1.09, 1.87) | 0.02 | 1.26 ** (1.01, 1.61) | 0.05 | |

| Caregiver activities 1 | 0.85 (0.46, 1.50) | 0.58 | 0.94 (0.61, 1.43) | 0.77 | 0.87 (0.51, 1.46) | 0.59 | |

| Postpartum anxiety | Has anxiety | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| No postpartum anxiety | 0.78 (0.15, 3.53) | 0.75 | 1.94 (0.56, 7.41) | 0.31 | 0.29 * (0.07, 1.12) | 0.08 | |

| Perceived stress | Low stress | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Moderate stress | 0.69 (0.15, 3.09) | 0.62 | 1.41 (0.42, 5.05) | 0.58 | 0.80 (0.23, 2.80) | 0.73 | |

| Grit scale 1 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 1.32 (0.34, 5.10) | 0.68 | |

| Participation in at least one of these: hotbed, mother roasting or steam sauna | Did not participate | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Participated in at least one | N/A | N/A | 0.44 (0.07, 3.04) | 0.38 | 0.91 (0.10, 9.26) | 0.93 | |

| Confinement duration 1 | 1.00 (0.95, 1.05) | 0.87 | 1.03 (0.99, 1.06) | 0.13 | 0.97 * (0.94, 1.00) | 0.06 | |

| Variable | Category | Randomised Controlled Trial Arm | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | Unconditional Social Transfer | Conditional Social Transfer | |||||

| HR (95% CI) | p | HR (95% CI) | p | HR (95% CI) | p | ||

| Age | Younger than 25 | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Between 25 and 30 | 1.03 (0.53, 2.01) | 0.92 | 1.12 (0.57, 2.18) | 0.75 | 1.73 (0.77, 3.92) | 0.19 | |

| Older than 30 | 0.61 (0.33, 1.10) | 0.10 | 0.92 (0.48, 1.78) | 0.81 | 1.52 (0.59, 3.90) | 0.39 | |

| Marital status | Not married | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Married or cohabitating | 1.97 (0.65, 5.99) | 0.23 | 1.03 (0.36, 2.95) | 0.96 | 2.08 (0.70, 6.15) | 0.19 | |

| Maternal education | Primary or no education | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Secondary | 2.07 * (0.95, 4.48) | 0.07 | 1.11 (0.54, 2.29) | 0.77 | 0.93 (0.42, 2.06) | 0.86 | |

| Tertiary | 1.26 (0.54, 2.93) | 0.60 | 0.78 (0.34, 1.78) | 0.56 | 1.19 (0.53, 2.66) | 0.67 | |

| Employment status at six months | Not working | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Working | 1.43 (0.78, 2.63) | 0.24 | 2.32 ** (1.06, 5.09) | 0.04 | 0.95 (0.43, 2.11) | 0.90 | |

| Household wealth 1 | 0.94 (0.76, 1.17) | 0.60 | 1.13 (0.87, 1.48) | 0.35 | 0.92 (0.71, 1.19) | 0.55 | |

| Previous births | Never given birth | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| At least one previous birth | 1.51 (0.89, 2.56) | 0.13 | 1.32 (0.64, 2.72) | 0.44 | 1.08 (0.60, 1.94) | 0.80 | |

| Intention to feed the baby | Complementary feeding | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Exclusive breastfeeding | 1.22 (0.67, 2.21) | 0.52 | 0.80 (0.29, 2.20) | 0.66 | 0.88 (0.34, 2.30) | 0.80 | |

| Desire for the pregnancy | Did not want the pregnancy | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Wanted the pregnancy | 1.04 (0.29, 3.78) | 0.95 | 0.47 (0.19, 1.16) | 0.10 | 1.29 (0.44, 3.74) | 0.64 | |

| Breastfeeding self-efficacy 1 | 0.89 * (0.78, 1.01) | 0.08 | 0.87 ** (0.77, 0.98) | 0.02 | 0.95 (0.86, 1.05) | 0.30 | |

| Caregiver activities 1 | 1.06 (0.83, 1.35) | 0.64 | 1.08 (0.87, 1.33) | 0.50 | 1.18 (0.92, 1.50) | 0.19 | |

| Postpartum anxiety | Has anxiety | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| No postpartum anxiety | 1.22 (0.70, 2.30) | 0.43 | 1.16 (0.67, 2.00) | 0.59 | 1.58 (0.85, 2.91) | 0.15 | |

| Perceived stress | Low stress | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Moderate stress | 1.13 (0.65, 1.97) | 0.67 | 1.16 (0.69, 1.93) | 0.58 | 0.97 (0.54, 1.73) | 0.91 | |

| Grit scale 1 | 0.52 (0.21, 1.29) | 0.16 | 0.51 * (0.25, 1.05) | 0.07 | 1.04 (0.56, 1.92) | 0.91 | |

| Participation in at least one of these: hotbed, mother roasting or steam sauna | Did not participate | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Participated in at least one | 1.00 (0.41, 2.44) | 0.99 | 1.51 (0.59, 3.88) | 0.39 | 0.90 (0.35, 2.35) | 0.83 | |

| Confinement duration 1 | 1.00 (0.99, 1.02) | 0.87 | 0.99 * (0.97, 1.00) | 0.10 | 1.00 (0.99, 1.02) | 0.53 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Karimian-Marnani, N.; Tilley, E.; Wallenborn, J.T. Overcoming Barriers to Exclusive Breastfeeding in Lao PDR: Social Transfer Intervention Randomised Controlled Trial. Nutrients 2025, 17, 2396. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17152396

Karimian-Marnani N, Tilley E, Wallenborn JT. Overcoming Barriers to Exclusive Breastfeeding in Lao PDR: Social Transfer Intervention Randomised Controlled Trial. Nutrients. 2025; 17(15):2396. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17152396

Chicago/Turabian StyleKarimian-Marnani, Najmeh, Elizabeth Tilley, and Jordyn T. Wallenborn. 2025. "Overcoming Barriers to Exclusive Breastfeeding in Lao PDR: Social Transfer Intervention Randomised Controlled Trial" Nutrients 17, no. 15: 2396. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17152396

APA StyleKarimian-Marnani, N., Tilley, E., & Wallenborn, J. T. (2025). Overcoming Barriers to Exclusive Breastfeeding in Lao PDR: Social Transfer Intervention Randomised Controlled Trial. Nutrients, 17(15), 2396. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17152396