Group Dialectical Behavior Therapy for Binge Eating Disorder: Emotion Dysregulation and Alexithymia as Mediators of Symptom Improvement

Abstract

1. Introduction

Study Aims and Hypotheses

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethical Considerations

2.2. Participants

2.3. Treatment

2.4. Study Design

- Binge Eating Scale (BES) [46]: The BES is a self-report questionnaires specifically designed to assess the presence and severity of binge eating symptomatology, and it was used in this study as the primary outcome measure. The scale consists of 16 items, each describing a set of statements that capture key behavioural and emotional aspects of binge eating episodes. These include the loss of control over eating, eating large amounts of food in a short time, feelings of guilt and shame, emotional distress related to eating and difficulties in stopping eating once started. Scores range from 0 to 46, with higher scores indicating a greater severity of binge eating pathology. The BES has demonstrated good psychometric properties, including internal consistency and construct validity [46], and it shows a moderate correlation with binge eating severity as assessed through food diaries and behavioural observations [47]. Cronbach’s Alpha was very good in the present sample (α = 0.89)

- Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale (DERS) [48]: A 36-item self-report questionnaire designed to assess multiple aspects of emotion regulation. The total score was analyzed, which is the sum of six subscale scores: Non-Acceptance of Emotional Responses, Difficulties Engaging in Goal-Directed Behaviour, Impulse Control Difficulties, Lack of Emotional Awareness, Limited Access to Emotion Regulation Strategies and Lack of Emotional Clarity. Higher scores indicate greater difficulty in emotion regulation. Internal consistency was good (α = 0.88).

- Toronto Alexithymia Scale (TAS-20) [49]: This scale is a widely used self-reported measure of alexithymia that assesses three factors: difficulty identifying feelings (Factor 1), difficulty describing feelings (Factor 2) and externally oriented thinking (Factor 3). Internal consistency was adequate (α = 0.75) in the present sample.

2.5. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. The Characteristics of the Sample

3.2. Longitudinal Analysis

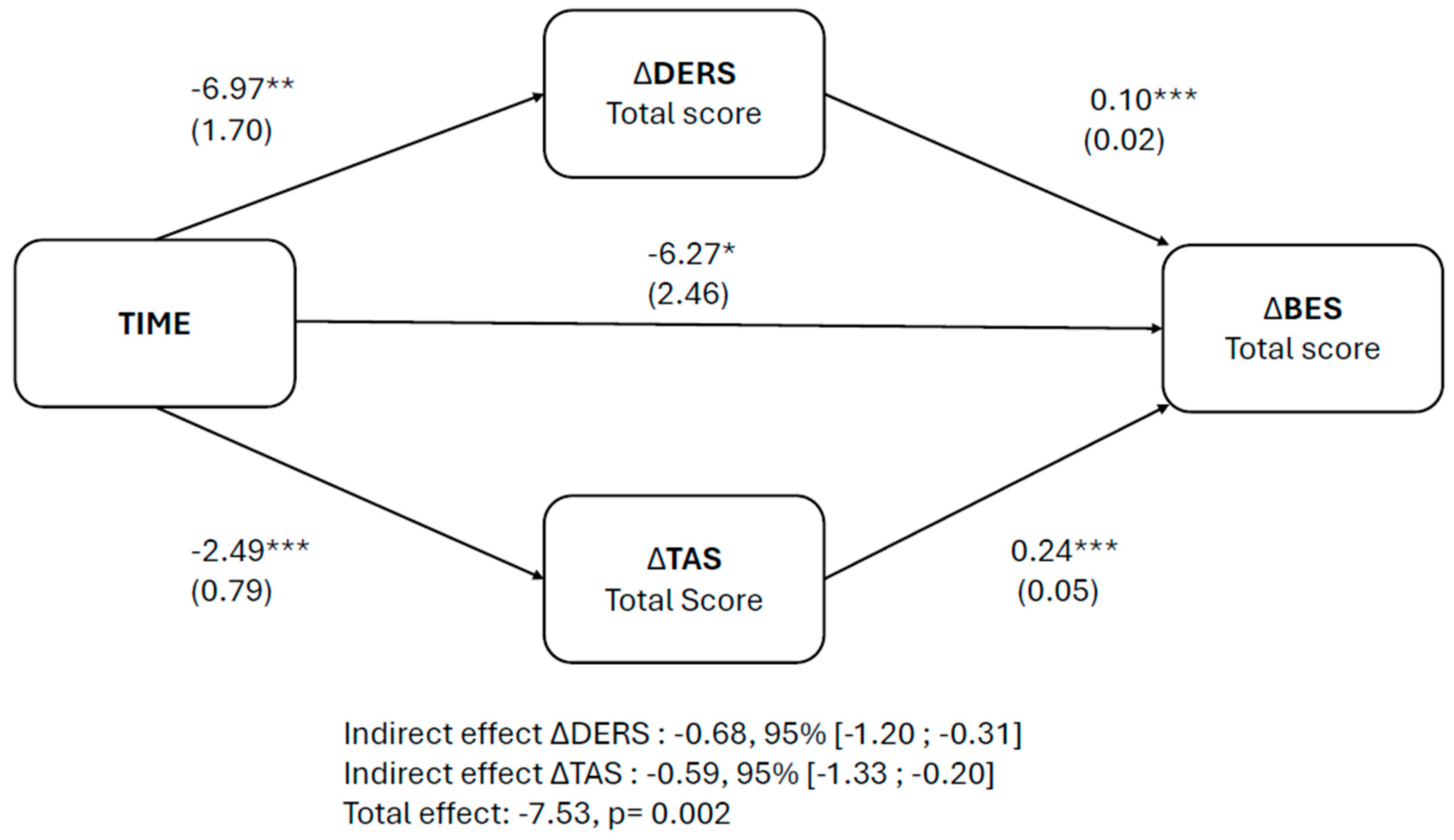

3.3. Longitudinal Mediation Model

4. Discussion

4.1. Key Findings

4.2. Clinical Implications

4.3. Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Qian, J.; Wu, Y.; Liu, F.; Zhu, Y.; Jin, H.; Zhang, H.; Wan, Y.; Li, C.; Yu, D. An Update on the Prevalence of Eating Disorders in the General Population: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Eat. Weight Disord. 2022, 27, 415–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silvestri, C.; Carpita, B.; Cassioli, E.; Lazzeretti, M.; Rossi, E.; Messina, V.; Castellini, G.; Ricca, V.; Dell’Osso, L.; Bolognesi, S.; et al. Prevalence Study of Mental Disorders in an Italian Region. Preliminary Report. BMC Psychiatry 2023, 23, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: Fifth Edition Text Revision DSM-5-TR; American Psychiatric Association Publishing: Washington, DC, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Monell, E.; Clinton, D.; Birgegård, A. Emotion Dysregulation and Eating Disorders-Associations with Diagnostic Presentation and Key Symptoms. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2018, 51, 921–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson, C.M.; Wonderlich, S.A.; Smith, G.T. A Risk and Maintenance Model for Bulimia Nervosa: From Impulsive Action to Compulsive Behavior. Psychol. Rev. 2015, 122, 516–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Racine, S.E.; Wildes, J.E. Emotion Dysregulation and Symptoms of Anorexia Nervosa: The Unique Roles of Lack of Emotional Awareness and Impulse Control Difficulties When Upset. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2013, 46, 713–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walenda, A.; Bogusz, K.; Kopera, M.; Jakubczyk, A.; Wojnar, M.; Kucharska, K. Emotion Regulation in Binge Eating Disorder. Psychiatr. Pol. 2021, 55, 1433–1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, R.A. Emotion Regulation: A Theme in Search of Definition. Monogr. Soc. Res. Child. Dev. 1994, 59, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, R.A. Emotion Dysregulation: A Theme in Search of Definition. Dev. Psychopathol. 2019, 31, 805–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, L.; Masson, P.; Safer, D.; von Ranson, K. Change in Emotion Regulation during the Course of Treatment Predicts Binge Abstinence in Guided Self-Help Dialectical Behavior Therapy for Binge Eating Disorder. J. Eat. Disord. 2014, 2, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battaglini, A.M.; Rnic, K.; Jameson, T.; Jopling, E.; Albert, A.Y.; LeMoult, J. The Association of Emotion Regulation Flexibility and Negative and Positive Affect in Daily Life. Affect. Sci. 2022, 3, 673–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.S.; Bi, K.; Han, X.; Sun, P.; Bonanno, G.A. Emotion Regulation Flexibility and Momentary Affect in Two Cultures. Nat. Ment. Health 2024, 2, 450–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dingemans, A.; Danner, U.; Parks, M. Emotion Regulation in Binge Eating Disorder: A Review. Nutrients 2017, 9, 1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nemiah, J.C. Alexithymia. Theoretical Considerations. Psychother. Psychosom. 1977, 28, 199–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sifneos, P.E. The Prevalence of “Alexithymic” Characteristics in Psychosomatic Patients. Psychother. Psychosom. 1973, 22, 255–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luminet, O.; Zamariola, G. Emotion Knowledge and Emotion Regulation in Alexithymia. In Alexithymia; Luminet, O., Bagby, R.M., Taylor, G.J., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2018; pp. 49–77. ISBN 978-1-108-24159-5. [Google Scholar]

- Preece, D.; Becerra, R.; Allan, A.; Robinson, K.; Dandy, J. Establishing the Theoretical Components of Alexithymia via Factor Analysis: Introduction and Validation of the Attention-Appraisal Model of Alexithymia. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2017, 119, 341–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preece, D.A.; Mehta, A.; Petrova, K.; Sikka, P.; Bjureberg, J.; Becerra, R.; Gross, J.J. Alexithymia and Emotion Regulation. J. Affect. Disord. 2023, 324, 232–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kittel, R.; Brauhardt, A.; Hilbert, A. Cognitive and emotional functioning in binge-eating disorder: A systematic review. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2015, 48, 535–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenardy, J.; Arnow, B.; Agras, W.S. The Aversiveness of Specific Emotional States Associated with Binge-Eating in Obese Subjects. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 1996, 30, 839–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilbert, A. Psychological and Medical Treatments for Binge-Eating Disorder: A Research Update. Physiol. Behav. 2023, 269, 114267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grilo, C.M.; Juarascio, A. Binge-Eating Disorder Interventions: Review, Current Status, and Implications. Curr. Obes. Rep. 2023, 12, 406–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linehan, M. Dialectical Behavior Therapy for Borderline Personality Disorder. Theory and Method. Bull. Menn. Clin. 1987, 51, 261–276. [Google Scholar]

- Neacsiu, A.D.; Eberle, J.W.; Kramer, R.; Wiesmann, T.; Linehan, M.M. Dialectical Behavior Therapy Skills for Transdiagnostic Emotion Dysregulation: A Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial. Behav. Res. Ther. 2014, 59, 40–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerolini, S.; D’Amico, M.; Zagaria, A.; Mocini, E.; Monda, G.; Donini, L.M.; Lombardo, C. A Brief Online Intervention Based on Dialectical Behavior Therapy for a Reduction in Binge-Eating Symptoms and Eating Pathology. Nutrients 2024, 16, 2696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizvi, S.L.; Bitran, A.M.; Oshin, L.A.; Yin, Q.; Ruork, A.K. The State of the Science: Dialectical Behavior Therapy. Behav. Ther. 2024, 55, 1233–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogel, E.N.; Singh, S.; Accurso, E.C. A Systematic Review of Cognitive Behavior Therapy and Dialectical Behavior Therapy for Adolescent Eating Disorders. J. Eat. Disord. 2021, 9, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Linehan, M. DBT Skills Training Manual, 2nd ed.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA; London, UK, 2015; ISBN 978-1-4625-1699-5. [Google Scholar]

- APA The American Psychiatric Association. Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients with Eating Disorders, 4th ed.; American Psychiatric Association Publishing: Washington, DC, USA, 2023; ISBN 978-0-89042-584-8. [Google Scholar]

- NICE. Eating Disorders: Recognition and Treatment (NG69); NICE: Manchester, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Iacovino, J.M.; Gredysa, D.M.; Altman, M.; Wilfley, D.E. Psychological Treatments for Binge Eating Disorder. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2012, 14, 432–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linardon, J.; Fairburn, C.G.; Fitzsimmons-Craft, E.E.; Wilfley, D.E.; Brennan, L. The Empirical Status of the Third-Wave Behaviour Therapies for the Treatment of Eating Disorders: A Systematic Review. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2017, 58, 125–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rozakou-Soumalia, N.; Dârvariu, Ş.; Sjögren, J.M. Dialectical Behaviour Therapy Improves Emotion Dysregulation Mainly in Binge Eating Disorder and Bulimia Nervosa: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Pers. Med. 2021, 11, 931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Telch, C.F.; Agras, W.S.; Linehan, M.M. Dialectical Behavior Therapy for Binge Eating Disorder. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2001, 69, 1061–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiser, S.; Telch, C.F. Dialectical Behavior Therapy for Binge-Eating Disorder. J. Clin. Psychol. 1999, 55, 755–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, E.Y.; Cacioppo, J.; Fettich, K.; Gallop, R.; McCloskey, M.S.; Olino, T.; Zeffiro, T.A. An Adaptive Randomized Trial of Dialectical Behavior Therapy and Cognitive Behavior Therapy for Binge-Eating. Psychol. Med. 2017, 47, 703–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lammers, M.; Vroling, M.; Crosby, R.; van Strien, T. Dialectical Behavior Therapy Compared to Cognitive Behavior Therapy in Binge-eating Disorder: An Effectiveness Study with 6-month Follow-up. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2022, 55, 902–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Telch, C.F.; Agras, W.S.; Linehan, M.M. Group Dialectical Behavior Therapy for Binge-Eating Disorder: A Preliminary, Uncontrolled Trial. Behav. Ther. 2000, 31, 569–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blood, L.; Adams, G.; Turner, H.; Waller, G. Group Dialectical Behavioral Therapy for Binge-Eating Disorder: Outcomes from a Community Case Series. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2020, 53, 1863–1867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adams, G.; Turner, H.; Hoskins, J.; Robinson, A.; Waller, G. Effectiveness of a Brief Form of Group Dialectical Behavior Therapy for Binge-eating Disorder: Case Series in a Routine Clinical Setting. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2021, 54, 615–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, A.H.; Safer, D.L. Moderators of Dialectical Behavior Therapy for Binge Eating Disorder: Results from a Randomized Controlled Trial. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2012, 45, 597–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, K.E.; Goldschmidt, A.B. Treatment of Binge-Eating Disorder Across the Lifespan: An Updated Review of the Literature and Considerations for Future Research. Curr. Obes. Rep. 2024, 13, 195–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castellini, G.; Caini, S.; Cassioli, E.; Rossi, E.; Marchesoni, G.; Rotella, F.; De Bonfioli Cavalcabo’, N.; Fontana, M.; Mezzani, B.; Alterini, B.; et al. Mortality and Care of Eating Disorders. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2023, 147, 122–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- First, M.B.; Williams, J.B.W.; Karg, R.S.; Spitzer, R.L. SCID-5-CV: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-5 Disorders: Clinician Version; American Psychiatric Association Publishing: Arlington, VA, USA, 2016; ISBN 978-1-58562-461-4. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann, T.C.; Glasziou, P.P.; Boutron, I.; Milne, R.; Perera, R.; Moher, D.; Altman, D.G.; Barbour, V.; Macdonald, H.; Johnston, M.; et al. Better Reporting of Interventions: Template for Intervention Description and Replication (TIDieR) Checklist and Guide. BMJ 2014, 348, g1687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imperatori, C.; Innamorati, M.; Lamis, D.A.; Contardi, A.; Continisio, M.; Castelnuovo, G.; Manzoni, G.M.; Fabbricatore, M. Factor Structure of the Binge Eating Scale in a Large Sample of Obese and Overweight Patients Attending Low Energy Diet Therapy. Eur. Eat. Disord. Rev. 2016, 24, 174–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timmerman, G.M. Binge Eating Scale: Further Assessment of Validity and Reliability. J. Appl. Biobehav. Res. 1999, 4, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sighinolfi, C.; Pala, A.N.; Chiri, L.R.; Marchetti, I.; Sica, C. Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale (DERS): Traduzione e Adattamento Italiano. [Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale (DERS): The Italian Translation and Adaptation]. Psicoter. Cogn. E Comport. 2010, 16, 141–170. [Google Scholar]

- Bressi, C.; Taylor, G.; Parker, J.; Bressi, S.; Brambilla, V.; Aguglia, E.; Allegranti, I.; Bongiorno, A.; Giberti, F.; Bucca, M.; et al. Cross Validation of the Factor Structure of the 20-Item Toronto Alexithymia Scale: An Italian Multicenter Study. J. Psychosom. Res. 1996, 41, 551–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- R Core Team R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Core Team: Vienna, Austria, 2025.

- Pinheiro, J.; Bates, D.; R Core Team. Linear and Nonlinear Mixed Effects Models_R Package, version 3.1-164 2023; R Core Team: Vienna, Austria, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Rossel, Y. Lavaan: An R Package for Structural Equation Modeling. J. Stat. Softw. 2012, 48, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safer, D.L.; Jo, B. Outcome from a Randomized Controlled Trial of Group Therapy for Binge Eating Disorder: Comparing Dialectical Behavior Therapy Adapted for Binge Eating to an Active Comparison Group Therapy. Behav. Ther. 2010, 41, 106–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassioli, E.; Rossi, E.; D’Anna, G.; Martelli, M.; Hazzard, V.M.; Crosby, R.D.; Wonderlich, S.A.; Ricca, V.; Castellini, G. A 1-Year Follow-up Study of the Longitudinal Interplay between Emotion Dysregulation and Childhood Trauma in the Treatment of Anorexia Nervosa. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2022, 55, 98–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goetz, D.B.; Johnson, E.C.; Naugle, A.E.; Borges, L.M. Alexithymia, State-emotion Dysregulation, and Eating Disorder Symptoms: A Mediation Model. Clin. Psychol. 2020, 24, 166–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricca, V.; Castellini, G.; Lo Sauro, C.; Ravaldi, C.; Lapi, F.; Mannucci, E.; Rotella, C.; Faravelli, C. Correlations between Binge Eating and Emotional Eating in a Sample of Overweight Subjects. Appetite 2009, 53, 418–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, E.; Cassioli, E.; Dani, C.; Marchesoni, G.; Monteleone, A.M.; Wonderlich, S.A.; Ricca, V.; Castellini, G. The Maltreated Eco-Phenotype of Eating Disorders: A New Diagnostic Specifier? A Systematic Review of the Evidence and Comprehensive Description. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2024, 160, 105619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meneguzzo, P.; Garolla, A.; Bonello, E.; Todisco, P. Alexithymia, Dissociation and Emotional Regulation in Eating Disorders: Evidence of Improvement through Specialized Inpatient Treatment. Clin. Psychol. Psychother. 2022, 29, 718–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muir, X.; Preece, D.A.; Becerra, R. Alexithymia and Eating Disorder Symptoms: The Mediating Role of Emotion Regulation. Aust. Psychol. 2024, 59, 121–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reilly, E.E.; Brown, T.A.; Arunagiri, V.; Kaye, W.H.; Wierenga, C.E. Exploring Changes in Alexithymia throughout Intensive Dialectical Behavior Therapy for Eating Disorders. Eur. Eat. Disord. Rev. 2022, 30, 193–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trompeter, N.; Bussey, K.; Forbes, M.K.; Mitchison, D. Emotion Dysregulation within the CBT-E Model of Eating Disorders: A Narrative Review. Cogn. Ther. Res. 2021, 45, 1021–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waller, G.; Tatham, M.; Turner, H.; Mountford, V.A.; Bennetts, A.; Bramwell, K.; Dodd, J.; Ingram, L. A 10-Session Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy (CBT-T) for Eating Disorders: Outcomes from a Case Series of Nonunderweight Adult Patients. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2018, 51, 262–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellini, G.; Cassioli, E.; Rossi, E.; Marchesoni, G.; Cerini, G.; Pastore, E.; De Bonfioli Cavalcabo’, N.; Rotella, F.; Mezzani, B.; Alterini, B.; et al. Use and Misuse of the Emergency Room by Patients with Eating Disorders in a Matched-Cohort Analysis: What Can We Learn from It? Psychiatry Res. 2023, 328, 115427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fairburn, C.G. Cognitive Behavior Therapy and Eating Disorders; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2008; pp. xii, 324. ISBN 978-1-59385-709-7. [Google Scholar]

- Forbush, K.T.; Hagan, K.E.; Kite, B.A.; Chapa, D.A.N.; Bohrer, B.K.; Gould, S.R. Understanding Eating Disorders within Internalizing Psychopathology: A Novel Transdiagnostic, Hierarchical-Dimensional Model. Compr. Psychiatry 2017, 79, 40–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forbush, K.T.; Chen, P.-Y.; Hagan, K.E.; Chapa, D.A.N.; Gould, S.R.; Eaton, N.R.; Krueger, R.F. A New Approach to Eating-Disorder Classification: Using Empirical Methods to Delineate Diagnostic Dimensions and Inform Care. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2018, 51, 710–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotov, R.; Krueger, R.F.; Watson, D.; Achenbach, T.M.; Althoff, R.R.; Bagby, R.M.; Brown, T.A.; Carpenter, W.T.; Caspi, A.; Clark, L.A.; et al. The Hierarchical Taxonomy of Psychopathology (HiTOP): A Dimensional Alternative to Traditional Nosologies. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2017, 126, 454–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deisenhofer, A.-K.; Barkham, M.; Beierl, E.T.; Schwartz, B.; Aafjes-van Doorn, K.; Beevers, C.G.; Berwian, I.M.; Blackwell, S.E.; Bockting, C.L.; Brakemeier, E.-L.; et al. Implementing Precision Methods in Personalizing Psychological Therapies: Barriers and Possible Ways Forward. Behav. Res. Ther. 2024, 172, 104443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, U.H.; Claudino, A.; Fernández-Aranda, F.; Giel, K.E.; Griffiths, J.; Hay, P.J.; Kim, Y.-R.; Marshall, J.; Micali, N.; Monteleone, A.M.; et al. The Current Clinical Approach to Feeding and Eating Disorders Aimed to Increase Personalization of Management. World Psychiatry 2025, 24, 4–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zipfel, S.; Lutz, W.; Schneider, S.; Schramm, E.; Delgadillo, J.; Giel, K.E. The Future of Enhanced Psychotherapy: Towards Precision Psychotherapy. Psychother. Psychosom. 2024, 93, 230–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monteleone, A.M.; Abbate-Daga, G. Effectiveness and Predictors of Psychotherapy in Eating Disorders: State-of-the-Art and Future Directions. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 2024, 37, 417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pennesi, J.-L.; Johnson, C.; Radünz, M.; Wade, T.D. Acute Augmentations to Psychological Therapies in Eating Disorders: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2024, 26, 447–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rossi, E.; Cassioli, E.; Cecci, L.; Arganini, F.; Martelli, M.; Redaelli, C.A.; Anselmetti, S.; Bertelli, S.; Fernandez, I.; Ricca, V.; et al. Eye Movement Desensitisation and Reprocessing as Add-on Treatment to Enhanced Cognitive Behaviour Therapy for Patients with Anorexia Nervosa Reporting Childhood Maltreatment: A Quasi-Experimental Multicenter Study. Eur. Eat. Disord. Rev. 2024, 32, 322–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giel, K.E.; Bulik, C.M.; Fernandez-Aranda, F.; Hay, P.; Keski-Rahkonen, A.; Schag, K.; Schmidt, U.; Zipfel, S. Binge Eating Disorder. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2022, 8, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Scales | T0 | T1 | Time Effect | Time Effect 95% CI | Cohen’s d |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total BES Score | 26.36 ± 7.73 | 21.11 ± 7.78 | −5.39 *** | −7.02–−3.76 | −0.69 |

| DERS: Non-Acceptance of Emotional Response | 18.04 ± 6.68 | 15.26 ± 6.20 | −2.40 ** | −3.86–−0.95 | −0.25 |

| DERS: Difficulty Engaging in Goal-Directed Behaviour | 18.00 ± 5.15 | 15.47 ± 4.95 | −1.70 ** | −2.98–−0.43 | −0.18 |

| DERS: Emotion Regulation Strategies | 26.15 ± 5.02 | 22.50 ± 5.34 | −3.18 *** | −4.55–−1.81 | −0.45 |

| DERS: Impulse Control Difficulties | 19.09 ± 6.33 | 15.98 ± 5.72 | −1.33 | −2.83–0.17 | −0.16 |

| DERS: Lack of Emotional Clarity | 16.29 ± 4.33 | 14.21 ± 4.23 | −1.36 ** | −2.36–−0.36 | −0.26 |

| DERS: Lack of Emotional Awareness | 9.48 ± 3.35 | 8.16 ± 3.31 | −1.23 ** | −2.10–−0.36 | −0.41 |

| Total DERS Score | 116.40 ± 25.42 | 100.26 ± 24.70 | −11.15 *** | −16.64–−5.67 | −0.41 |

| TAS: Difficulty Identifying Feelings | 23.10 ± 6.37 | 21.08 ± 6.23 | −2.04 ** | −3.52–−0.56 | −0.27 |

| TAS: Difficulty Describing Feelings | 15.75 ± 4.47 | 15.32 ± 4.47 | −0.44 | −1.72–0.84 | −0.13 |

| TAS: Externally Oriented Thinking | 19.59 ± 5.32 | 18.92 ± 5.33 | −0.87 | −2.10–0.36 | −0.22 |

| Total TAS Score | 58.44 ± 12.17 | 55.32 ± 12.85 | −3.42 * | −6.43–−0.40 | −0.30 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zompa, L.; Cassioli, E.; Rossi, E.; Cordasco, V.Z.; Caiati, L.; Lucarelli, S.; Giunti, I.; Lazzeretti, L.; D’Anna, G.; Dei, S.; et al. Group Dialectical Behavior Therapy for Binge Eating Disorder: Emotion Dysregulation and Alexithymia as Mediators of Symptom Improvement. Nutrients 2025, 17, 2003. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17122003

Zompa L, Cassioli E, Rossi E, Cordasco VZ, Caiati L, Lucarelli S, Giunti I, Lazzeretti L, D’Anna G, Dei S, et al. Group Dialectical Behavior Therapy for Binge Eating Disorder: Emotion Dysregulation and Alexithymia as Mediators of Symptom Improvement. Nutrients. 2025; 17(12):2003. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17122003

Chicago/Turabian StyleZompa, Luca, Emanuele Cassioli, Eleonora Rossi, Valentina Zofia Cordasco, Leda Caiati, Stefano Lucarelli, Ilenia Giunti, Lisa Lazzeretti, Giulio D’Anna, Simona Dei, and et al. 2025. "Group Dialectical Behavior Therapy for Binge Eating Disorder: Emotion Dysregulation and Alexithymia as Mediators of Symptom Improvement" Nutrients 17, no. 12: 2003. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17122003

APA StyleZompa, L., Cassioli, E., Rossi, E., Cordasco, V. Z., Caiati, L., Lucarelli, S., Giunti, I., Lazzeretti, L., D’Anna, G., Dei, S., Cardamone, G., Ricca, V., Rotella, F., & Castellini, G. (2025). Group Dialectical Behavior Therapy for Binge Eating Disorder: Emotion Dysregulation and Alexithymia as Mediators of Symptom Improvement. Nutrients, 17(12), 2003. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17122003