Effects of Perceived Stress on Problematic Eating: Three Parallel Moderated Mediation Models

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedure

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Perceived Stress

2.2.2. Problematic Eating

2.2.3. Irrational Health Beliefs

2.2.4. Negative Coping Styles

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics

3.2. Common Method Bias

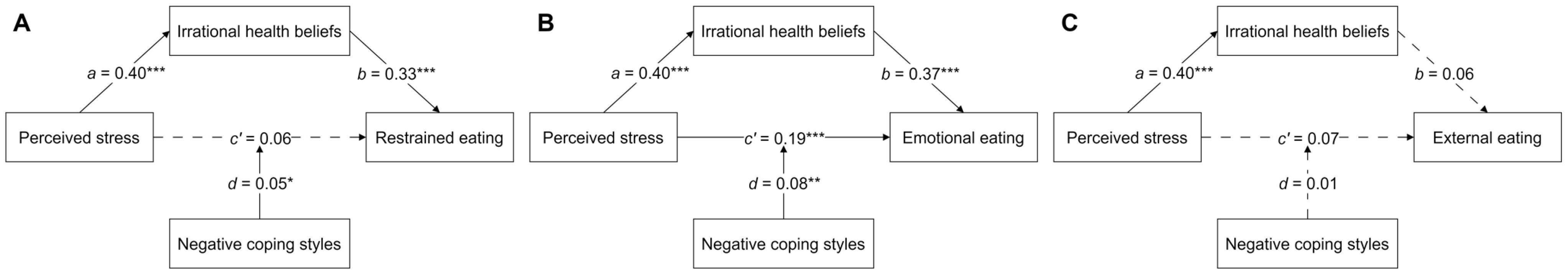

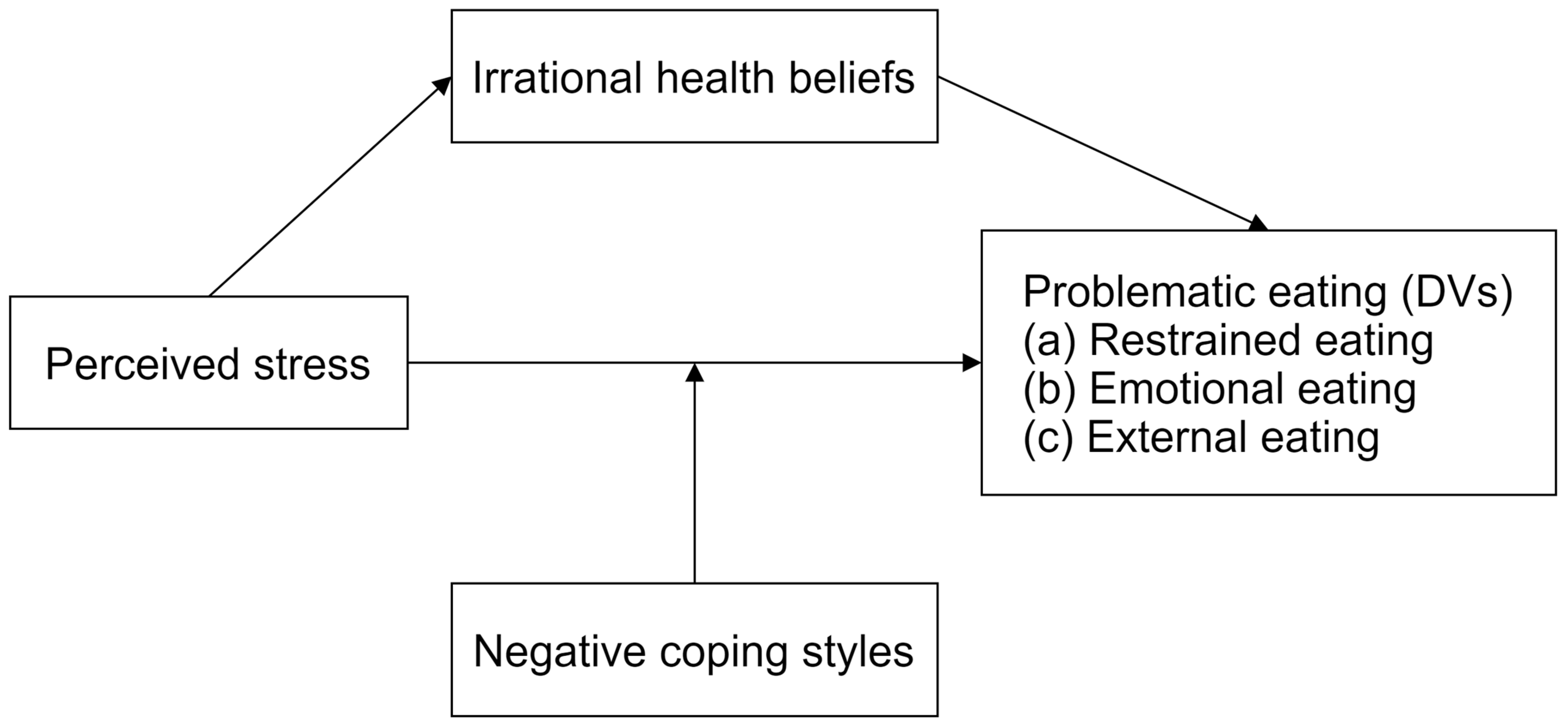

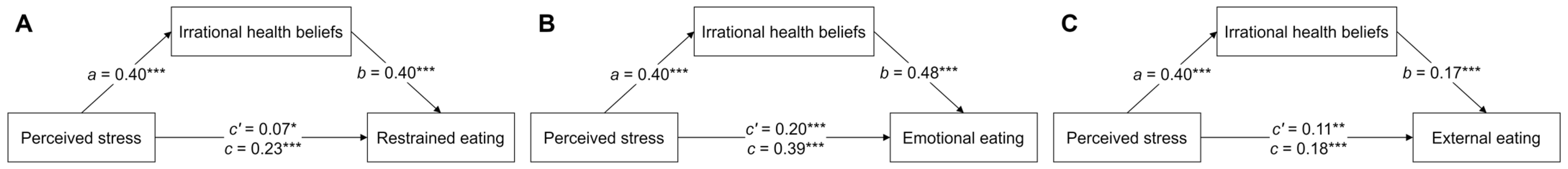

3.3. Mediation Models

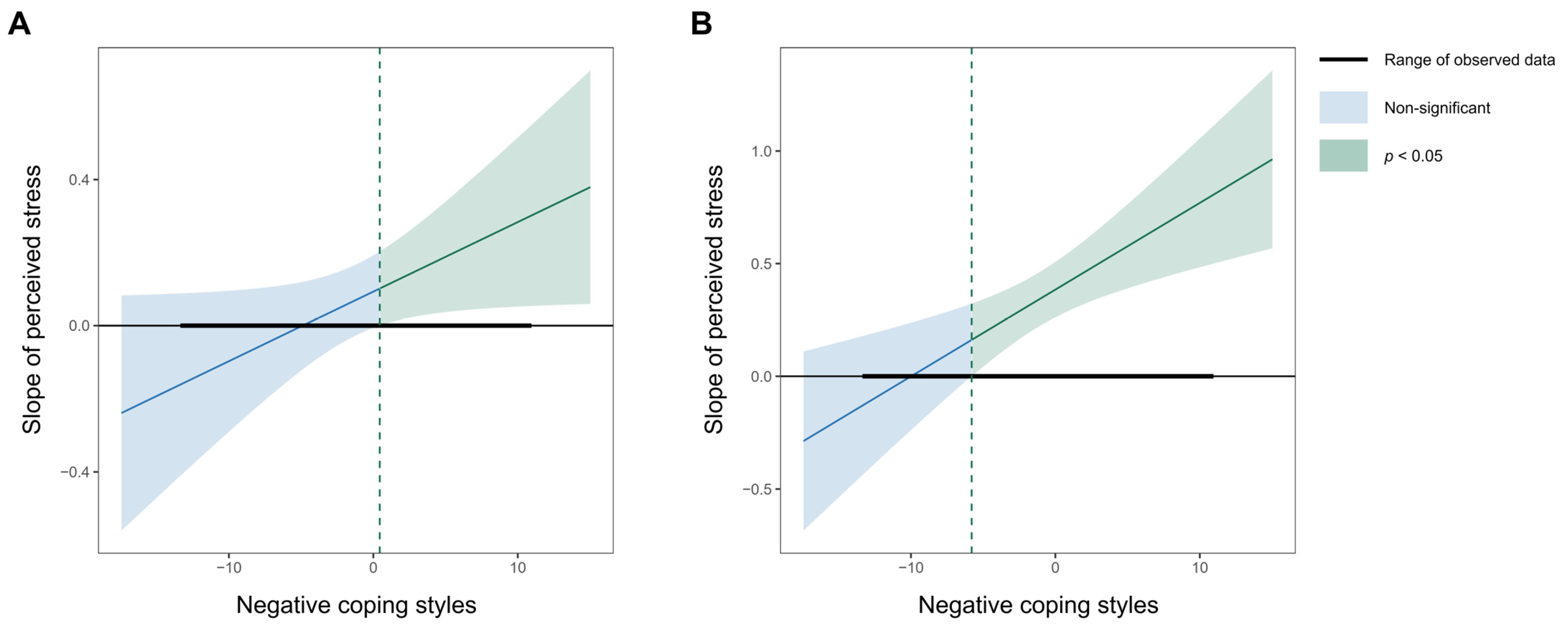

3.4. Moderated Mediation Models

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- Konttinen, H. Emotional eating and obesity in adults: The role of depression, sleep and genes. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2020, 79, 283–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benbaibeche, H.; Saidi, H.; Bounihi, A.; Koceir, E.A. Emotional and external eating styles associated with obesity. J. Eat. Disord. 2023, 11, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohde, P.; Stice, E.; Marti, C.N. Development and predictive effects of eating disorder risk factors during adolescence: Implications for prevention efforts. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2015, 48, 187–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernabéu-Brotóns, E.; Marchena-Giráldez, C. Emotional eating and perfectionism as predictors of symptoms of binge eating disorder: The role of perfectionism as a mediator between emotional eating and body mass index. Nutrients 2022, 14, 3361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenbaum, D.L.; White, K.S. The relation of anxiety, depression, and stress to binge eating behavior. J. Health Psychol. 2015, 20, 887–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, M.C.; Parsons, S.; Goglio, A.; Fox, E. Anxiety, stress, and binge eating tendencies in adolescence: A prospective approach. J. Eat. Disord. 2021, 9, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, D.C.; Moss, R.H.; Sykes-Muskett, B.; Conner, M.; O’Connor, D.B. Stress and eating behaviors in children and adolescents: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Appetite 2018, 123, 14–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, D.; Conner, M.; Clancy, F.; Moss, R.; Wilding, S.; Bristow, M.; O’Connor, D.B. Stress and eating behaviours in healthy adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Health Psychol. Rev. 2022, 16, 280–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalo, E.; Konttinen, H.; Westerterp-Plantenga, M.; Adam, T.; Drummen, M.; Huttunen-Lenz, M.; Siig Vestentoft, P.; Martinez, J.A.; Handjiev, S.; Macdonald, I.; et al. Perceived stress as a predictor of eating behavior during the 3-year PREVIEW lifestyle intervention. Nutr. Diabetes 2022, 12, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norrish, A.; Cox, R.; Simpson, A.; Bergmeier, H.; Bruce, L.; Savaglio, M.; Pizzirani, B.; O’Donnell, R.; Smales, M.; Skouteris, H. Understanding problematic eating in out-of-home care: The role of attachment and emotion regulation. Appetite 2019, 135, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czepczor-Bernat, K.; Brytek-Matera, A. Children’s and mothers’ perspectives of problematic eating behaviours in young children and adolescents: An exploratory study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 2692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, J.G.; Larkin, T.A.; Deng, C.; Thomas, S.J. Cortisol in relation to problematic eating behaviours, adiposity and symptom profiles in Major Depressive Disorder. Compr. Psychoneuroendocrinol. 2021, 7, 100067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mills, J.G.; Thomas, S.J.; Larkin, T.A.; Pai, N.B.; Deng, C. Problematic eating behaviours, changes in appetite, and weight gain in Major Depressive Disorder: The role of leptin. J. Affect. Disord. 2018, 240, 137–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Strien, T.; Frijters, J.E.; Bergers, G.P.; Defares, P.B. The Dutch Eating Behavior Questionnaire (DEBQ) for assessment of restrained, emotional, and external eating behavior. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 1986, 5, 295–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, J.R.; Capurro, G.; Saumann, M.P.; Slachevsky, A. Problematic eating behaviors and nutritional status in 7 to 12 year-old Chilean children. Int. J. Clin. Health Psychol. 2013, 13, 32–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalkowska, J.; Hamulka, J.; Wadolowska, L.; Górnicka, M.; Czarniecka-Skubina, E.; Gutkowska, K. Restrained eating and disinhibited eating: Association with diet quality and body weight status among adolescents. Nutrients 2024, 16, 3601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller-Matero, L.R.; Armstrong, R.; McCulloch, K.; Hyde-Nolan, M.; Eshelman, A.; Genaw, J. To eat or not to eat; is that really the question? An evaluation of problematic eating behaviors and mental health among bariatric surgery candidates. Eat. Weight Disord.-Stud. Anorex. 2014, 19, 377–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akduman, I.; Sevincer, G.M.; Bozkurt, S.; Kandeger, A. The relationship between childhood maltreatment and problematic eating behaviors in bariatric surgery candidates. Eat. Weight Disord.-Stud. Anorex. 2021, 26, 1357–1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sims, R.; Gordon, S.; Garcia, W.; Clark, E.; Monye, D.; Callender, C.; Campbell, A. Perceived stress and eating behaviors in a community-based sample of African Americans. Eat. Behav. 2008, 9, 137–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groesz, L.M.; McCoy, S.; Carl, J.; Saslow, L.; Stewart, J.; Adler, N.; Laraia, B.; Epel, E. What is eating you? Stress and the drive to eat. Appetite 2012, 58, 717–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, A.S.; Arsenault, J.E.; Cates, S.C.; Muth, M.K. Perceived stress, unhealthy eating behaviors, and severe obesity in low-income women. Nutr. J. 2015, 14, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuluhong, M.; Han, P. Chronic stress is associated with reward and emotion-related eating behaviors in college students. Front. Nutr. 2023, 9, 1025953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yilmazturk, N.H.; Demir, A.; Celik-Orucu, M. The mediator role of emotion-focused coping on the relationship between perceived stress and emotional eating. Trends Psychol. 2023, 31, 383–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpenter, C.J. A meta-analysis of the effectiveness of health belief model variables in predicting behavior. Health Commun. 2010, 25, 661–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenstock, I.M. Why people use health services. Milbank Mem. Fund Q. 1966, 44, 94–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenstock, I.M. Historical origins of the health belief model. Health Educ. Monogr. 1974, 2, 328–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, A.J.; Moran, P.J.; Wiebe, J.S. Assessment of irrational health beliefs: Relation to health practices and medical regimen adherence. Health Psychol. 1999, 18, 169–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Afsahi, F.; Kachooei, M. Relationship between hypertension with irrational health beliefs and health locus of control. J. Educ. Health Promot. 2020, 9, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fathabadi, J.; Izaddost, M.; Taghavi, D.; Shalani, B.; Sadeghi, S. The role of irrational health beliefs, health locus of control and health-oriented lifestyle in predicting the risk of diabetes. Payesh 2018, 17, 169–178. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, D.R.; Emery, C.F. Irrational health beliefs predict adherence to cardiac rehabilitation: A pilot study. Health Psychol. 2014, 33, 1614–1617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fulton, J.J.; Marcus, D.K.; Merkey, T. Irrational health beliefs and health anxiety. J. Clin. Psychol. 2011, 67, 527–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rabalais, T.L. Understanding the Relationship of Stress, Irrational Health Beliefs, and Health Behaviors Among Adults 18–45 Years of Age. Ph.D. Thesis, Walden University, Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Dilorenzo, T.; David, D.; Montgomery, G.H. The impact of general and specific rational and irrational beliefs on exam distress; A further investigation of the binary model of distress as an emotional regulation model. J. Evid-Based Psychother. 2011, 11, 121–142. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis, A. Reason and Emotion in Psychotherapy; Birch Lane Press: Secaucus, NJ, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Beck, A.T. Cognitive Therapy of Depression; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis, A. A sadly neglected cognitive element in depression. Cogn. Ther. Res. 1987, 11, 121–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osberg, T.M.; Poland, D.; Aguayo, G.; MacDougall, S. The Irrational Food Beliefs Scale: Development and validation. Eat. Behav. 2008, 9, 25–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osberg, T.M.; Eggert, M. Direct and indirect effects of stress on bulimic symptoms and BMI: The mediating role of irrational food beliefs. Eat. Behav. 2012, 13, 54–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lazarus, R.; Folkman, S. Stress, Appraisal, and Coping; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, Y. Reliability and validity of the Simplified Coping Style Questionnaire. Chin. J. Clin. Psychol. 1998, 6, 114–115. [Google Scholar]

- Spoor, S.T.; Bekker, M.H.; Van Strien, T.; Van Heck, G.L. Relations between negative affect, coping, and emotional eating. Appetite 2007, 48, 368–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, N.H.; Risi, M.M.; Sullivan, T.P.; Armeli, S.; Tennen, H. Post-traumatic stress disorder symptom severity attenuates bi-directional associations between negative affect and avoidant coping: A daily diary study. J. Affect. Disord. 2019, 259, 73–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, M. Coping strategies initiated by COVID-19-related stress, individuals’ motives for social media use, and perceived stress reduction. Internet Res. 2023, 33, 124–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dallman, M.F.; Pecoraro, N.; Akana, S.F.; La Fleur, S.E.; Gomez, F.; Houshyar, H.; Bell, M.E.; Bhatnagar, S.; Laugero, K.D.; Manalo, S. Chronic stress and obesity: A new view of “comfort food”. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 11696–11701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomiyama, A.J.; Dallman, M.F.; Epel, E.S. Comfort food is comforting to those most stressed: Evidence of the chronic stress response network in high stress women. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2011, 36, 1513–1519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomiyama, A.J.; Finch, L.E.; Cummings, J.R. Did that brownie do its job? Stress, eating, and the biobehavioral effects of comfort food. Emerg. Trends Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 1, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulrich-Lai, Y.M. Self-medication with sucrose. Curr. Opin. Behav. Sci. 2016, 9, 78–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Young, D.; Limbers, C.A. Avoidant coping moderates the relationship between stress and depressive emotional eating in adolescents. Eat. Weight Disord.-Stud. Anorex. 2017, 22, 683–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalton, E.D. Emotional eating in college students: Associations with coping and healthy eating motivators and barriers. Int. J. Behav. Med. 2024, 31, 563–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Chen, J.; Boyd, J.E.; Zhang, H.; Jia, X.; Qiu, J.; Xiao, Z. Psychometric properties of the Chinese version of the Perceived Stress Scale in policewomen. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e28610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S.; Kamarck, T.; Mermelstein, R. A global measure of perceived stress. J. Health Soc. Behav. 1983, 24, 385–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.H. Review of the psychometric evidence of the perceived stress scale. Asian Nurs. Res. 2012, 6, 121–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, W.; Bian, Q.; Wang, W.; Wu, X.; Wang, Z.; Zhao, M. Chinese version of the Perceived Stress Scale-10: A psychometric study in Chinese university students. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0189543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Tian, X.; Zhang, G.; Liu, J.; Zhao, S. Reliability and validity of the Perceived Stress Scale short form (PSS10) for Chinese college students. Psychol. Explor. 2021, 41, 343–348. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, C.; Ma, H.; Luo, Y.; Fong, D.Y.T.; Umucu, E.; Zheng, H.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, X.; Liu, X.; Spruyt, K.; et al. Validation of the Chinese version of the Perceived Stress Scale-10 integrating exploratory graph analysis and confirmatory factor analysis. Gen. Hosp. Psych. 2023, 84, 194–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kong, F. The Neural Mechanisms in Attentional Bias on Food Cues for Restraint Eaters. Ph.D. Thesis, Southwest University, Chongqing, China, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Liu, Y.; Bao, J. The applicability of Dutch Eating Behavior Questionnaire (DEBQ) in Chinese college students. Chin. J. Clin. Psychol. 2018, 26, 277–281+326. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis, 7th ed.; Pearson: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Malhotra, N.K.; Kim, S.S.; Patil, A. Common method variance in IS research: A comparison of alternative approaches and a reanalysis of past research. Manag. Sci. 2006, 52, 1865–1883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, M.; Quinn, L.; Park, C.; Martyn-Nemeth, P. Pathways of the relationships among eating behavior, stress, and coping in adults with type 2 diabetes: A cross-sectional study. Appetite 2018, 131, 84–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohara, K.; Mase, T.; Kouda, K.; Miyawaki, C.; Momoi, K.; Fujitani, T.; Fujita, Y.; Nakamura, H. Association of anthropometric status, perceived stress, and personality traits with eating behavior in university students. Eat. Weight Disord.-Stud. Anorex. 2019, 24, 521–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Wang, Z.; Guo, B.; Arcelus, J.; Zhang, H.; Jia, X.; Xu, Y.; Qiu, J.; Xiao, Z.; Yang, M. Negative affect mediates effects of psychological stress on disordered eating in young Chinese women. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e46878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, J.; Zahry, N.R. Relationships among perceived stress, emotional eating, and dietary intake in college students: Eating self-regulation as a mediator. Appetite 2021, 163, 105215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, R.F. The relationship between health-related knowledge and attitudes and health risk behaviours among Portuguese university students. Glob. Health Promot. 2024, 31, 36–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiebe, J.S.; Christensen, A.J. Health beliefs, personality, and adherence in hemodialysis patients: An interactional perspective. Ann. Behav. Med. 1997, 19, 30–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitel, L.; Ballová Mikušková, E. The Irrational Health Beliefs Scale and health behaviors in a non-clinical population. Eur. J. Health Psychol. 2021, 28, 111–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodino, I.S.; Gignac, G.E.; Sanders, K.A. Stress has a direct and indirect effect on eating pathology in infertile women: Avoidant coping style as a mediator. Reprod. Biomed. Soc. Online. 2018, 5, 110–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulkowski, M.L.; Dempsey, J.; Dempsey, A.G. Effects of stress and coping on binge eating in female college students. Eat. Behav. 2011, 12, 188–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ball, K.; Lee, C. Relationships between psychological stress, coping and disordered eating: A review. Psychol. Health 2000, 14, 1007–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finch, L.E.; Tomiyama, A.J. Comfort eating, psychological stress, and depressive symptoms in young adult women. Appetite 2015, 95, 239–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gibson, E.L. The psychobiology of comfort eating: Implications for neuropharmacological interventions. Behav. Pharmacol. 2012, 23, 442–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, T.; Wang, J.; Xu, S.; Yu, J.; Sun, G. Media internalized pressure and restrained eating behavior in college students: The multiple mediating effects of body esteem and social physique anxiety. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 887124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Musharaf, S. Prevalence and predictors of emotional eating among healthy young Saudi women during the COVID-19 pandemic. Nutrients 2020, 12, 2923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schachter, S. Obesity and eating. Internal and external cues differentially affect the eating behavior of obese and normal subjects. Science 1968, 161, 751–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daubenmier, J.; Kristeller, J.; Hecht, F.M.; Maninger, N.; Kuwata, M.; Jhaveri, K.; Lustig, R.H.; Kemeny, M.; Karan, L.; Epel, E. Mindfulness intervention for stress eating to reduce cortisol and abdominal fat among overweight and obese women: An exploratory randomized controlled study. J. Obes. 2011, 2011, 651936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linehan, M. Cognitive-Behavioral Treatment of Borderline Personality Disorder; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Pollard, T.M. Use of cortisol as a stress marker: Practical and theoretical problems. Am. J. Hum. Biol. 1995, 7, 265–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellhammer, D.H.; Wüst, S.; Kudielka, B.M. Salivary cortisol as a biomarker in stress research. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2009, 34, 163–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russell, E.; Koren, G.; Rieder, M.; Van Uum, S. Hair cortisol as a biological marker of chronic stress: Current status, future directions and unanswered questions. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2012, 37, 589–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variables | n (%) | Perceived Stress a | Restrained Eating a | Emotional Eating a | External Eating a | Irrational Health Beliefs a | Negative Coping Styles a |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 3.84 *** | 1.51 | 5.20 *** | −0.07 | 12.62 *** | 5.60 *** | |

| Male | 392 (42.2%) | ||||||

| Female | 537 (57.8%) | ||||||

| Education | 0.82 | 1.35 | 0.09 | 1.49 | 4.33 * | 1.47 | |

| Undergraduate | 851 (91.6%) | ||||||

| Master’s student | 74 (8.0%) | ||||||

| Doctoral student | 4 (0.4%) | ||||||

| Place of birth | 2.59 * | 5.07 *** | 3.27 ** | 1.83 | 5.48 *** | 3.37 *** | |

| City | 530 (57.1%) | ||||||

| Country | 399 (42.9%) | ||||||

| Only child status | 2.55 * | 4.83 *** | 5.23 *** | 2.08 * | 8.15 *** | 4.25 *** | |

| Only child | 416 (44.8%) | ||||||

| Non-only child | 513 (55.2%) | ||||||

| Nationality | 2.73 ** | 2.09 * | 2.42 * | 1.60 | 2.37 * | 0.62 | |

| Han | 864 (93.0%) | ||||||

| Minority | 65 (7.0%) |

| Variables | M (SD) | Range | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Age | 21.50 (2.36) | 17−35 | 1 | |||||||

| 2. BMI | 20.62 (2.61) | 13.06−32.60 | 0.08 * | 1 | ||||||

| 3. Perceived stress | 19.10 (6.22) | 0−37 | 0.16 *** | 0.07 * | 1 | |||||

| 4. Restrained eating | 30.71 (9.40) | 10−50 | 0.20 *** | 0.21 *** | 0.27 *** | 1 | ||||

| 5. Emotional eating | 36.64 (12.81) | 13−65 | 0.17 *** | 0.11 *** | 0.43 *** | 0.42 *** | 1 | |||

| 6. External eating | 34.83 (6.54) | 11−50 | 0.15 *** | 0.02 | 0.20 *** | 0.31 *** | 0.45 *** | 1 | ||

| 7. Irrational health beliefs | 56.13 (18.28) | 21−92 | 0.28 *** | 0.14 *** | 0.47 *** | 0.42 *** | 0.57 *** | 0.22 *** | 1 | |

| 8. Negative coping styles | 13.21 (4.23) | 0−24 | 0.24 *** | 0.10 ** | 0.40 *** | 0.35 *** | 0.49 *** | 0.30 *** | 0.57 *** | 1 |

| Variables | Equation 1: Irrational Health Beliefs | Equation 2: Restrained Eating | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | SE | t | Bootstrap 95% CI | β | SE | t | Bootstrap 95% CI | |||

| LLCI | ULCI | LLCI | ULCI | |||||||

| Age | 0.14 | 0.03 | 4.92 *** | 0.09 | 0.20 | 0.07 | 0.03 | 2.08 * | 0.00 | 0.13 |

| Gender | −0.28 | 0.03 | −9.65 *** | −0.33 | −0.22 | 0.21 | 0.03 | 6.28 *** | 0.14 | 0.27 |

| Education | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.98 | −0.03 | 0.08 | −0.02 | 0.03 | −0.65 | −0.08 | 0.04 |

| Place of birth | −0.04 | 0.03 | −1.39 | −0.10 | 0.02 | −0.08 | 0.03 | −2.51 * | −0.14 | −0.02 |

| Only child status | −0.12 | 0.03 | −3.91 *** | −0.17 | −0.06 | −0.02 | 0.03 | −0.68 | −0.09 | 0.04 |

| Nationality | 0.00 | 0.03 | 0.05 | −0.05 | 0.05 | −0.02 | 0.03 | −0.56 | −0.07 | 0.04 |

| BMI | −0.01 | 0.03 | −0.20 | −0.06 | 0.05 | 0.20 | 0.03 | 6.66 *** | 0.14 | 0.26 |

| Perceived stress | 0.40 | 0.03 | 14.95 *** | 0.35 | 0.45 | 0.06 | 0.03 | 1.84 | 0.00 | 0.13 |

| Irrational health beliefs | 0.33 | 0.04 | 8.20 *** | 0.25 | 0.40 | |||||

| Negative coping styles | 0.15 | 0.04 | 4.13 *** | 0.08 | 0.22 | |||||

| Perceived stress × Negative coping styles | 0.05 | 0.03 | 1.98 * | 0.00 | 0.11 | |||||

| R | 0.61 | 0.52 | ||||||||

| R2 | 0.37 | 0.27 | ||||||||

| F (df) | 68.14 *** (8, 920) | 30.25 *** (11, 917) | ||||||||

| Variables | Equation 1: Irrational Health Beliefs | Equation 2: Emotional Eating | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | SE | t | Bootstrap 95% CI | β | SE | t | Bootstrap 95% CI | |||

| LLCI | ULCI | LLCI | ULCI | |||||||

| Age | 0.14 | 0.03 | 4.92 *** | 0.09 | 0.20 | 0.00 | 0.03 | −0.11 | −0.06 | 0.05 |

| Gender | −0.28 | 0.03 | −9.65 *** | −0.33 | −0.22 | 0.06 | 0.03 | 2.12 * | 0.00 | 0.12 |

| Education | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.98 | −0.03 | 0.08 | −0.04 | 0.03 | −1.59 | −0.10 | 0.01 |

| Place of birth | −0.04 | 0.03 | −1.39 | −0.10 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.30 | −0.05 | 0.06 |

| Only child status | −0.12 | 0.03 | −3.91 *** | −0.17 | −0.06 | −0.03 | 0.03 | −0.94 | −0.09 | 0.03 |

| Nationality | 0.00 | 0.03 | 0.05 | −0.05 | 0.05 | −0.03 | 0.03 | −1.05 | −0.08 | 0.02 |

| BMI | −0.01 | 0.03 | −0.20 | −0.06 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 1.43 | −0.01 | 0.09 |

| Perceived stress | 0.40 | 0.03 | 14.95 *** | 0.35 | 0.45 | 0.19 | 0.03 | 6.14 *** | 0.13 | 0.25 |

| Irrational health beliefs | 0.37 | 0.04 | 10.31 *** | 0.30 | 0.44 | |||||

| Negative coping styles | 0.23 | 0.03 | 7.10 *** | 0.17 | 0.30 | |||||

| Perceived stress × Negative coping styles | 0.08 | 0.02 | 3.25 ** | 0.03 | 0.13 | |||||

| R | 0.61 | 0.63 | ||||||||

| R2 | 0.37 | 0.40 | ||||||||

| F (df) | 68.14 *** (8, 920) | 55.10 *** (11, 917) | ||||||||

| Variables | Equation 1: Irrational Health Beliefs | Equation 2: External Eating | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | SE | t | Bootstrap 95% CI | β | SE | t | Bootstrap 95% CI | |||

| LLCI | ULCI | LLCI | ULCI | |||||||

| Age | 0.14 | 0.03 | 4.92 *** | 0.09 | 0.20 | 0.10 | 0.03 | 2.82 ** | 0.03 | 0.17 |

| Gender | −0.28 | 0.03 | −9.65 *** | −0.33 | −0.22 | 0.10 | 0.04 | 2.76 ** | 0.03 | 0.17 |

| Education | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.98 | −0.03 | 0.08 | −0.07 | 0.03 | −1.99 * | −0.13 | 0.00 |

| Place of birth | −0.04 | 0.03 | −1.39 | −0.10 | 0.02 | −0.01 | 0.03 | −0.25 | −0.08 | 0.06 |

| Only child status | −0.12 | 0.03 | −3.91 *** | −0.17 | −0.06 | −0.02 | 0.04 | −0.43 | −0.09 | 0.05 |

| Nationality | 0.00 | 0.03 | 0.05 | −0.05 | 0.05 | −0.04 | 0.03 | −1.39 | −0.11 | 0.02 |

| BMI | −0.01 | 0.03 | −0.20 | −0.06 | 0.05 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.18 | −0.06 | 0.07 |

| Perceived stress | 0.40 | 0.03 | 14.95 *** | 0.35 | 0.45 | 0.07 | 0.03 | 1.96 | 0.00 | 0.14 |

| Irrational health beliefs | 0.06 | 0.04 | 1.34 | −0.03 | 0.14 | |||||

| Negative coping styles | 0.23 | 0.04 | 5.81 *** | 0.15 | 0.31 | |||||

| Perceived stress × Negative coping styles | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.18 | −0.05 | 0.06 | |||||

| R | 0.61 | 0.34 | ||||||||

| R2 | 0.37 | 0.12 | ||||||||

| F (df) | 68.14 *** (8, 920) | 10.91 *** (11, 917) | ||||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Guo, H.; Ye, Z.; Han, J.; Luo, Y.; Chen, H. Effects of Perceived Stress on Problematic Eating: Three Parallel Moderated Mediation Models. Nutrients 2025, 17, 1928. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17111928

Guo H, Ye Z, Han J, Luo Y, Chen H. Effects of Perceived Stress on Problematic Eating: Three Parallel Moderated Mediation Models. Nutrients. 2025; 17(11):1928. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17111928

Chicago/Turabian StyleGuo, Haoyu, Ziyi Ye, Jinfeng Han, Yijun Luo, and Hong Chen. 2025. "Effects of Perceived Stress on Problematic Eating: Three Parallel Moderated Mediation Models" Nutrients 17, no. 11: 1928. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17111928

APA StyleGuo, H., Ye, Z., Han, J., Luo, Y., & Chen, H. (2025). Effects of Perceived Stress on Problematic Eating: Three Parallel Moderated Mediation Models. Nutrients, 17(11), 1928. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17111928