Health Consciousness, Sensory Appeal, and Perception of Front-of-Package Food Labels as Predictors of Purchase Intention for Unhealthy Foods in Peruvian University Students

Abstract

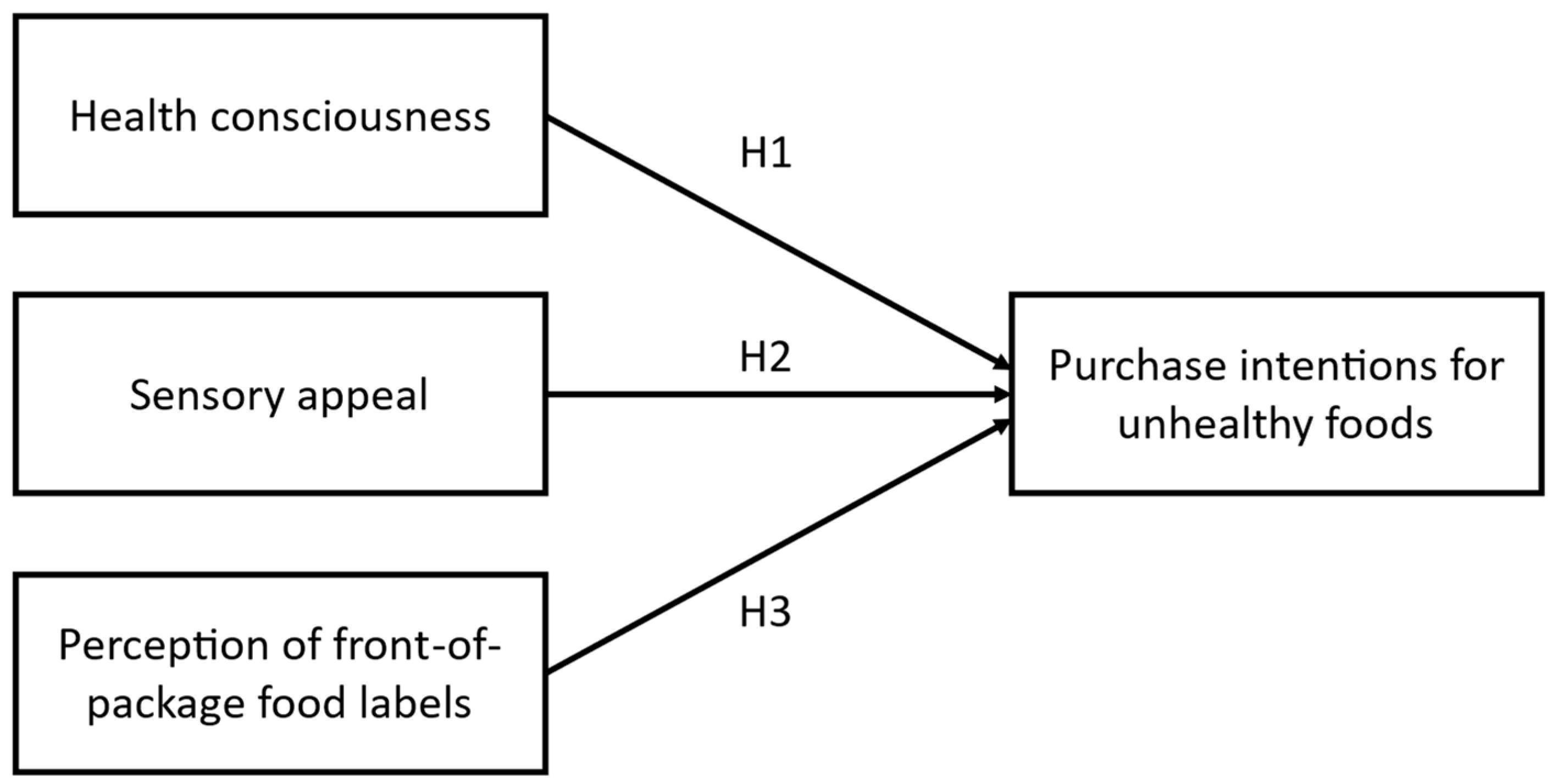

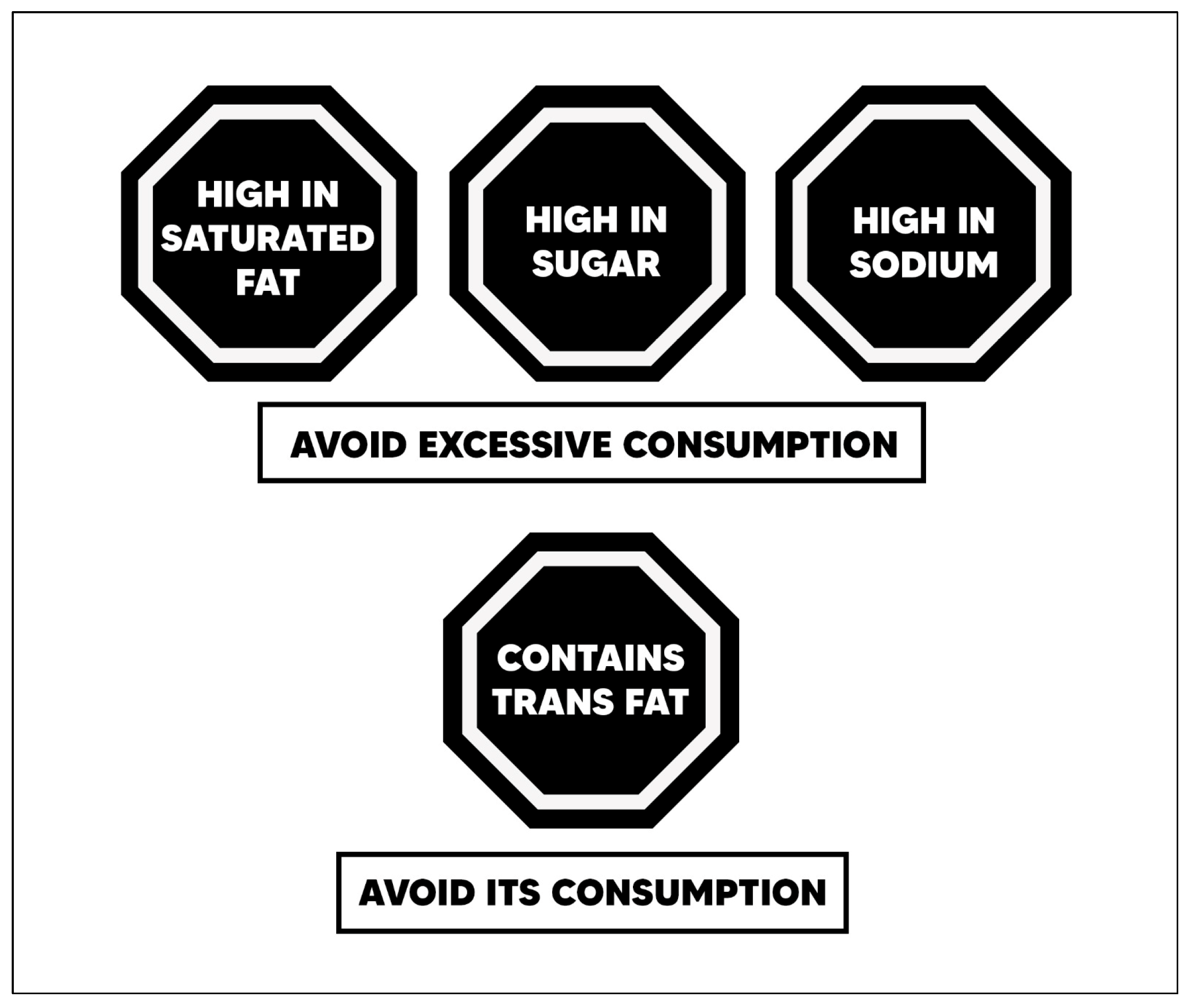

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design and Participants

2.2. Ethical Aspects

2.3. Variables

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| FOP | front-of-package |

References

- Castro, I.A.; Majmundar, A.; Williams, C.B.; Baquero, B. Customer Purchase Intentions and Choice in Food Retail Environments: A Scoping Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 2493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gould, S.J. Consumer Attitudes Toward Health and Health Care: A Differential Perspective. J. Consum. Aff. 1988, 22, 96–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.-H. Relationships between Consumers’ Nutritional Knowledge, Social Interaction, and Health-conscious Correlates toward the Restaurants. J. Int. Manag. Stud. 2014, 9, 59–63. [Google Scholar]

- Hoque, M.; Alam Md Nahid, K. Health Consciousness and Its Effect on Perceived Knowledge, and Belief in the Purchase Intent of Liquid Milk: Consumer Insights from an Emerging Market. Foods 2018, 7, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imtiyaz, H.; Soni, P.; Yukongdi, V. Role of Sensory Appeal, Nutritional Quality, Safety, and Health Determinants on Convenience Food Choice in an Academic Environment. Foods 2021, 10, 345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Detopoulou, P.; Dedes, V.; Syka, D.; Tzirogiannis, K.; Panoutsopoulos, G.I. Mediterranean Diet, a Posteriori Dietary Patterns, Time-Related Meal Patterns and Adiposity: Results from a Cross-Sectional Study in University Students. Diseases 2022, 10, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blondin, S.A.; Mueller, M.P.; Bakun, P.J.; Choumenkovitch, S.F.; Tucker, K.L.; Economos, C.D. Cross-Sectional Associations between Empirically-Derived Dietary Patterns and Indicators of Disease Risk among University Students. Nutrients 2015, 8, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hafiz, A.; Gallagher, A.; Devine, L.; Hill, A. University student practices and perceptions on eating behaviours whilst living away from home. Int. J. Educ. Res. 2023, 117, 102133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabir, A.; Miah, S.; Islam, A. Factors influencing eating behavior and dietary intake among resident students in a public university in Bangladesh: A qualitative study. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0198801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Pérez, Y.N.; Ramos-Guevara, Y.; Santa Cruz-López, C.Y.; Rivera-Salazar, C. Dietary and hygiene habits associated with the Helicobacter pylori seroprevalence in Peruvian university students. Rev. Inf. Científica 2021, 100, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- INEI. Perú: Enfermedades No Transmisibles y Transmisibles [Peru: Noncommunicable and Communicable Diseases, 2022]. Lima. 2022. Available online: https://www.gob.pe/institucion/inei/informes-publicaciones/4233635-peru-enfermedades-no-transmisibles-y-transmisibles-2022 (accessed on 12 November 2023).

- NCD Risk Factor Collaboration (NCD-RisC). Worldwide trends in diabetes since 1980: A pooled analysis of 751 population-based studies with 4.4 million participants. Lancet 2016, 387, 1513–1530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- INEI Perú: Enfermedades No Transmisibles y Transmisibles, 2021—Informes y publicaciones—Instituto Nacional de Estadística e Informática—Gobierno del Perú [Peru: Noncommunicable and Communicable Diseases, 2021—Reports and Publications—National Institute of Statistics and Informatics—Government of Peru]. Lima. 2021. Available online: https://www.gob.pe/institucion/inei/informes-publicaciones/2983123-peru-enfermedades-no-transmisibles-y-transmisibles-2021 (accessed on 14 September 2022).

- INEI. El 39,9% de Peruanos de 15 y Más Años de Edad Tiene al Menos una Comorbilidad [39.9% of Peruvians Aged 15 and Over Have at Least One Comorbidity]. 2020. Available online: https://www.inei.gob.pe/prensa/noticias/el-399-de-peruanos-de-15-y-mas-anos-de-edad-tiene-al-menos-una-comorbilidad-12903/ (accessed on 12 November 2023).

- WHF/WCC. The Cost of Heart Disease in Latin America. México City. 2016. Available online: https://www.world-heart-federation.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/spanish-press-release.pdf (accessed on 12 November 2023).

- Mohammad, M.; Chowdhury, M.A.B.; Islam, N.; Ahmed, A.; Zahan, F.N.; Akter, M.F.; Mila, S.N.; Tani, T.A.; Akter, T.; Islam, T.; et al. Health awareness, lifestyle and dietary behavior of university students in the northeast part of Bangladesh. Int. J. Adolesc. Med. Health 2021, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parashar, S.; Singh, S.; Sood, G. Examining the role of health consciousness, environmental awareness and intention on purchase of organic food: A moderated model of attitude. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 386, 135553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellison, B.; Lusk, J.L.; Davis, D. Looking at the label and beyond: The effects of calorie labels, health consciousness, and demographics on caloric intake in restaurants. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2013, 10, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giampietri, E.; Bugin, G.; Trestini, S. On the association between risk attitude and fruit and vegetable consumption: Insights from university students in Italy. Agric. Food Econ. 2021, 9, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grunert, K.G.; Wills, J.M. A review of European research on consumer response to nutrition information on food labels. J. Public Health 2007, 15, 385–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vainio, A.; Niva, M.; Jallinoja, P.; Latvala, T. From beef to beans: Eating motives and the replacement of animal proteins with plant proteins among Finnish consumers. Appetite 2016, 106, 92–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Macedo, I.C.; de Freitas, J.S.; da Silva Torres, I.L. The Influence of Palatable Diets in Reward System Activation: A Mini Review. Adv. Pharmacol. Sci. 2016, 2016, 7238679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCrickerd, K.; Forde, C.G. Sensory influences on food intake control: Moving beyond palatability. Obes. Rev. 2016, 17, 18–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adam Drewnowski, Eva Almiron-Roig. Human Perceptions and Preferences for Fat-Rich Foods. In Fat Detection: Taste, Texture, and Post Ingestive Effects; Montmayeur, J.-P., Ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2009; p. 28. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, E.; Blissett, J.; Higgs, S. Changing memory of food enjoyment to increase food liking, choice and intake. Br. J. Nutr. 2012, 108, 1505–1510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas-Meza, J.; Jáuregui, A.; Pacheco-Miranda, S.; Contreras-Manzano, A.; Barquera, S. Front-of-pack nutritional labels: Understanding by low- and middle-income Mexican consumers. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0225268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taillie, L.S.; Bercholz, M.; Popkin, B.; Reyes, M.; Colchero, M.A.; Corvalán, C. Changes in food purchases after the Chilean policies on food labelling, marketing, and sales in schools: A before and after study. Lancet Planet. Health 2021, 5, e526–e533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, J.; Brown, M.K.; Tan, M.; MacGregor, G.A.; Webster, J.; Campbell, N.R.C.; Trieu, K.; Ni Mhurchu, C.; Cobb, L.K.; He, F.J. Impact of color-coded and warning nutrition labelling schemes: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2021, 18, e1003765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, A.; Neal, B.; Reeve, B.; Ni Mhurchu, C.; Thow, A.M. Front-of-pack nutrition labelling to promote healthier diets: Current practice and opportunities to strengthen regulation worldwide. BMJ Glob. Health 2019, 4, e001882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alvarez-Cano, J.; Cavero, V.; Diez-Canseco, F. The comings and goings of the design of the healthy eating policy in Peru: A comparative analysis of its regulatory documents. Rev. Peru. Med. Exp. Salud Publica 2023, 39, 480–488. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, S.K.; Taillie, L.S.; Gupta, A.; Bercholz, M.; Popkin, B.; Murukutla, N. Front-of-Package Labels on Unhealthy Packaged Foods in India: Evidence from a Randomized Field Experiment. Nutrients 2022, 14, 3128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ato, M.; López, J.J.; Benavente, A. A classification system for research designs in psychology. Anales Psicología 2013, 29, 1038–1059. [Google Scholar]

- Jager, J.; Putnick, D.L.; Bornstein, M.H. More than Just Convenient: The Scientific Merits of Homogeneous Convenience Samples. Monogr. Soc. Res. Child. Dev. 2017, 82, 13–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soper, D. A-priori Sample Size Calculator for Multiple Regression. Software. 2022. Available online: https://www.danielsoper.com/statcalc/ (accessed on 14 November 2023).

- Yadav, R.; Pathak, G.S. Intention to purchase organic food among young consumers: Evidences from a developing nation. Appetite 2016, 96, 122–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cubas Vilca, S.S.; Rosas Rojas, A.M. Analysis of Factors Influencing the Intention to Purchase Organic Food in Metropolitan Lima in 2021; Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú: San Miguel, Peru, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Steptoe, A.; Pollard, T.M.; Wardle, J. Development of a Measure of the Motives Underlying the Selection of Food: The Food Choice Questionnaire. Appetite 1995, 25, 267–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, S.-L.; Hsu, C.-C.; Chen, H.-S. To Buy or Not to Buy? Consumer Attitudes and Purchase Intentions for Suboptimal Food. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eccoña, S. Percepción Sensorial, Intención de Compra y Expectativa Saludable del Consumidor Sobre la Carne de Cuy Envasada al Vacío; Universidad Nacional José Faustino Sánchez Carrión: Huacho, Peru, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Casas-Caruajulca, E.; Muguruza-Sanchez, L.J.; Calizaya-Milla, Y.E.; Saintila, J. Perception of frontal food labeling, purchase and consumption of ultra-processed foods during the COVID-19 quarantine: A cross-sectional study in the Peruvian population. Rev. Española De Nutr. Humana Y Dietética 2021, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mejía, C.R.; Pantaleón, C.A.; Alfaro, S.; Carranza, B.; Gálvez, A.; Eulogio, P.; Godo, G. Factores que influyen en el uso del octógono como marcador de información nutricional en los consumidores en la población de Lima-Perú. Nutr. Clín. Diet. Hosp. 2019, 39, 65–71. [Google Scholar]

- MINSA Conoce las advertencias publicitarias (octógonos). Gobierno del Perú. 2019. Available online: https://www.gob.pe/1066-ministerio-de-salud-conoce-las-advertencias-publicitarias-octogonos (accessed on 25 February 2025).

- Arvola, A.; Vassallo, M.; Dean, M.; Lampila, P.; Saba, A.; Lähteenmäki, L.; Shepherd, R. Predicting intentions to purchase organic food: The role of affective and moral attitudes in the Theory of Planned Behaviour. Appetite 2008, 50, 443–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forde, C.G.; de Graaf, K. Influence of Sensory Properties in Moderating Eating Behaviors and Food Intake. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 841444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khorisantono, P.A.; Huang, F.-Y.; Sutcliffe, M.P.F.; Fletcher, P.C.; Farooqi, I.S.; Grabenhorst, F. A Neural Mechanism in the Human Orbitofrontal Cortex for Preferring High-Fat Foods Based on Oral Texture. J. Neurosci. 2023, 43, 8000–8017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Sun, Z.; Feng, C.; Xiao, X.; Hou, Y. The Effect of Vice–Virtue Bundles on Consumers’ Purchase Intentions for Vice Packaged Foods: Evidence from Randomized Experiments. Foods 2023, 12, 3270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinhauser, J.; Janssen, M.; Hamm, U. Who Buys Products with Nutrition and Health Claims? A Purchase Simulation with Eye Tracking on the Influence of Consumers’ Nutrition Knowledge and Health Motivation. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, P.-Y.; Wood, W.; Monterosso, J. Healthy eating habits protect against temptations. Appetite 2016, 103, 432–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, S.; Doxey, J.; Hammond, D. Nutrition labels on pre-packaged foods: A systematic review. Public Health Nutr. 2011, 14, 1496–1506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Braakhuis, A.; Li, Z.; Roy, R. How Does the University Food Environment Impact Student Dietary Behaviors? A Systematic Review. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braesco, V.; Drewnowski, A. Are Front-of-Pack Nutrition Labels Influencing Food Choices and Purchases, Diet Quality, and Modeled Health Outcomes? A Narrative Review of Four Systems. Nutrients 2023, 15, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zafar, M.Z.; Shi, X.; Yang, H.; Abbas, J.; Chen, J. The Impact of Interpretive Packaged Food Labels on Consumer Purchase Intention: The Comparative Analysis of Efficacy and Inefficiency of Food Labels. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 15098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legget, K.T.; Cornier, M.-A.; Sarabia, L.; Delao, E.M.; Mikulich-Gilbertson, S.K.; Natvig, C.; Erpelding, C.; Mitchell, T.; Hild, A.; Kronberg, E.; et al. Sex Differences in Effects of Mood, Eating-Related Behaviors, and BMI on Food Appeal and Desire to Eat: A Cross-Sectional Survey Study. Nutrients 2023, 15, 762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez-Leon, S.; Pesantes, M.A.; Pastrana, N.A.; Raman, S.; Miranda, J.; Suggs, L.S. Food Perceptions and Dietary Changes for Chronic Condition Management in Rural Peru: Insights for Health Promotion. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flagg, L.A.; Sen, B.; Kilgore, M.L.; Locher, J.L. The influence of gender, age, education and household size on meal preparation and food shopping responsibilities. Public Health Nutr. 2014, 17, 2061–2070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saintila, J.; Carranza-Cubas, S.P.; Santamaria-Acosta, O.F.A.; Serpa-Barrientos, A.; Ramos-Vera, C.; López-López, E.; Geraldo-Campos, L.A.; Calizaya-Milla, Y.E. Breakfast consumption, saturated fat intake, and body mass index among medical and non-medical students: A cross-sectional analysis. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 12608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malinowska, D.; Milewski, R.; Żendzian-Piotrowska, M. Risk factors of colorectal cancer: The comparison of selected nutritional behaviors of medical and non-medical students. J. Health Popul. Nutr. 2023, 42, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taillie, L.S.; Bercholz, M.; Popkin, B.; Rebolledo, N.; Reyes, M.; Corvalán, C. Decreases in purchases of energy, sodium, sugar, and saturated fat 3 years after implementation of the Chilean food labeling and marketing law: An interrupted time series analysis. PLoS Med. 2024, 21, e1004463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basto-Abreu, A.; Torres-Alvarez, R.; Reyes-Sánchez, F.; González-Morales, R.; Canto-Osorio, F.; Colchero, M.A.; Barquera, S.; Rivera, J.A.; Barrientos-Gutierrez, T. Predicting obesity reduction after implementing warning labels in Mexico: A modeling study. PLoS Med. 2020, 17, e1003221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monterrosa, E.C.; Frongillo, E.A.; Drewnowski, A.; De Pee, S.; Vandevijvere, S. Sociocultural Influences on Food Choices and Implications for Sustainable Healthy Diets. Food Nutr. Bull. 2020, 41, 59S–73S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Darmon, N.; Drewnowski, A. Does social class predict diet quality? Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2008, 87, 1107–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andretti, B.; Vieites, Y.; Elmor, L.; Andrade, E.B. How Socioeconomic Status Shapes Food Preferences and Perceptions. J. Mark. 2025; Epub ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair Jnr, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis, 7th ed.; Pearson: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Nunnally. Psychometric Theory, 2nd ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, J. Impact of stress levels on eating behaviors among college students. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | ||

| 18 | 115 | 31.9 |

| 19–24 | 189 | 52.4 |

| >24 | 57 | 15.7 |

| Sex | ||

| Female | 210 | 58.2 |

| Male | 151 | 41.8 |

| Discipline of studies | ||

| Health Sciences | 125 | 34.6 |

| Other disciplines | 236 | 65.4 |

| Total | 361 | 100 |

| Variables | Male | Female | U * | p ** | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median | IQR (25–75) | Range (Min-Max) | Median | IQR (25–75) | Range (Min-Max) | |||

| Sensory appeal | 8.00 | 6.00–11.00 | 3.00–21.00 | 8.00 | 6.00–11.00 | 3.00–18.00 | 17,204.50 | 0.505 |

| Health consciousness | 8.00 | 6.00–10.00 | 3.00–21.00 | 8.00 | 6.00–10.00 | 3.00–17.00 | 16,009.50 | 0.073 |

| Perception of FOP food labels | 21.00 | 17.00–24.00 | 8.00–42.00 | 20.00 | 16.00–24.00 | 6.00–33.00 | 16,009.50 | 0.074 |

| Purchase intention for unhealthy food | 15.00 | 11.00–18.00 | 4.00–28.00 | 16.00 | 11.00–20.00 | 4.00–28.00 | 16,935.00 | 0.358 |

| Variables | Sensory Appeal | Health Consciousness | Perception of FOP Food Labels | Purchase Intention for Unhealthy Food |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sensory appeal | 1 | −0.080 | 0.069 | 0.346 ** |

| Health consciousness | −0.080 | 1 | 0.200 ** | −0.261 ** |

| Perception of FOP food labels | 0.069 | 0.200 ** | 1 | −0.221 ** |

| Purchase intention for unhealthy food | 0.346 ** | −0.261 ** | 0.221 ** | 1 |

| Model 1 | Unstandardized Coefficients | Standardized Coefficients | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE | β | t | p | |

| (Intercept) | 10.283 | 1.221 | - | 8.425 | <0.001 |

| health consciousness | −0.529 | 0.083 | −0.296 | −6.389 | <0.001 |

| Sensory appeal | 0.515 | 0.069 | 0.339 | 7.408 | <0.001 |

| Perception of FOP food labels | −0.238 | 0.047 | −0.237 | −5.114 | <0.001 |

| Sex | −0.320 | 0.070 | −0.190 | −4.571 | <0.001 |

| Age | −0.089 | 0.062 | −0.054 | −1.435 | 0.152 |

| Discipline of studies | −0.410 | 0.081 | −0.250 | −5.062 | <0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Saintila, J.; Florián-Castro, R.O.; Macedo-Barrera, E.M.; Pérez-Facundo, R.P.; Calizaya-Milla, Y.E. Health Consciousness, Sensory Appeal, and Perception of Front-of-Package Food Labels as Predictors of Purchase Intention for Unhealthy Foods in Peruvian University Students. Nutrients 2025, 17, 1921. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17111921

Saintila J, Florián-Castro RO, Macedo-Barrera EM, Pérez-Facundo RP, Calizaya-Milla YE. Health Consciousness, Sensory Appeal, and Perception of Front-of-Package Food Labels as Predictors of Purchase Intention for Unhealthy Foods in Peruvian University Students. Nutrients. 2025; 17(11):1921. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17111921

Chicago/Turabian StyleSaintila, Jacksaint, Rafael Orlando Florián-Castro, Eufemio Magno Macedo-Barrera, Raquel Patricia Pérez-Facundo, and Yaquelin E. Calizaya-Milla. 2025. "Health Consciousness, Sensory Appeal, and Perception of Front-of-Package Food Labels as Predictors of Purchase Intention for Unhealthy Foods in Peruvian University Students" Nutrients 17, no. 11: 1921. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17111921

APA StyleSaintila, J., Florián-Castro, R. O., Macedo-Barrera, E. M., Pérez-Facundo, R. P., & Calizaya-Milla, Y. E. (2025). Health Consciousness, Sensory Appeal, and Perception of Front-of-Package Food Labels as Predictors of Purchase Intention for Unhealthy Foods in Peruvian University Students. Nutrients, 17(11), 1921. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17111921