Bridging the Milk Gap: Integrating a Human Milk Bank–Blood Bank Model to Reinforce Lactation Support and Neonatal Care

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- i.

- Ensure the safe, efficient, equitable, and sustainable provision of DHM to meet the regional needs of patients.

- ii.

- Complement and strengthen the CHUV’s neonatal care, infant nutrition, and lactation support programs.

2. Methods

2.1. Design

2.2. Partnership Project Setting

2.3. Project Team and Management

- (1)

- Baseline needs assessment and model identification: This initial stage aimed to (i) quantify DHM needs using breastfeeding unit monitoring data, (ii) identify the most suitable HMB model through literature review, stakeholder consultations, on-site visits, and interdisciplinary expert meetings, and (iii) confirm the proposed solution via discussions with policymakers.

- (2)

- Development and preparation: This phase focused on (i) defining partners’ roles and responsibilities for future operations, (ii) preparing documentation, protocols, and workflows, and (iii) procuring, analyzing, and qualifying the necessary equipment. These tasks were performed by joint working groups and overseen by the steering committee.

- (3)

- Launch: This phase centered on (i) operationalizing workflows, (ii) monitoring key performance indicators, and (iii) adjusting processes based on early outcomes.

- (4)

- Operational and monitoring phase: This phase intended to (i) consolidate practices, (ii) conduct regular reviews involving the operational group, steering committee, institutional leaders, and public health authorities, and (iii) optimize processes through continuous data monitoring.

2.4. Continuous Data Monitoring

- Human milk volumetry (volumes of human milk collected, pasteurized, analyzed, qualified, delivered, administered, discarded).

- Donor information (demographic data, medical and nutritional histories, lifestyle factors, serology results, documented informed consent).

- Recipient patient data (demographics, medical indications for DHM, parental consent).

- Clinical outcomes (neonatal mortality rates, associated complications, and duration of hospital stays).

- Nutrition and breastfeeding outcomes (duration of enteral and parenteral nutrition, volumes of MOM and DHM and/or formula intake during hospitalization, as well as breastfeeding rates recorded at initiation and discharge).

- A dedicated human milk banking module integrated into the TIR TCS v1.1 software by Mak-System©, which facilitates real-time monitoring and guarantees traceability, quality, and safety across all operational steps.

- CHUV’s lacto-vigilance software (Almalacté© v1.24.1.0) ensures the safety and full traceability of milk from the medical prescription and ordering to its administration to the patient.

- CHUV’s electronic patient medical record system (Soarian© v4.7.100 and Metavision© v6.14).

- Swiss Minimal Neonatal Data Set, which collects the benchmarking data of neonates born between ≥22 and <32 weeks gestational age or with birth weight between 400 g and 1500 g in Swiss Level III and IIb neonatal care centers.

2.5. Ethics

3. Results

3.1. Phase 1: Baseline Needs Assessment and Model Identification—2020

- -

- Leveraging complementary expertise of the CHUV in neonatal care, nutrition, and lactation support and the TIR’s expertise in donation management, quality-controlled processing, and distribution of MPHOs.

- -

- Mutualizing existing infrastructures and resources, such as the breastfeeding rooms at CHUV, the TIR laboratories, and serological testing services, alongside the integration and adaptation of IT systems and the use of existing logistics and transport networks between the CHUV and TIR facilitated the development of processes. The TIR’s regional transport system enabled the collection of milk directly from the donors’ homes, a strategy shown to enhance the sustainability of human milk donation [37]. Moreover, merging these infrastructures and services significantly reduced initial investment costs.

- -

- Safety and quality assurance: HMB operations align with a rigorous, ethical, quality, and safety framework, based on TIR’s standards for human blood product processing and donor management, fully compliant with good manufacturing practices (GMP).

- -

- Regulatory perspectives: the project incorporated considerations of evolving frameworks, particularly the ongoing European harmonization of human milk banking under the SoHO framework [23].

3.2. Phase 2: Project Development and Preparation—2021

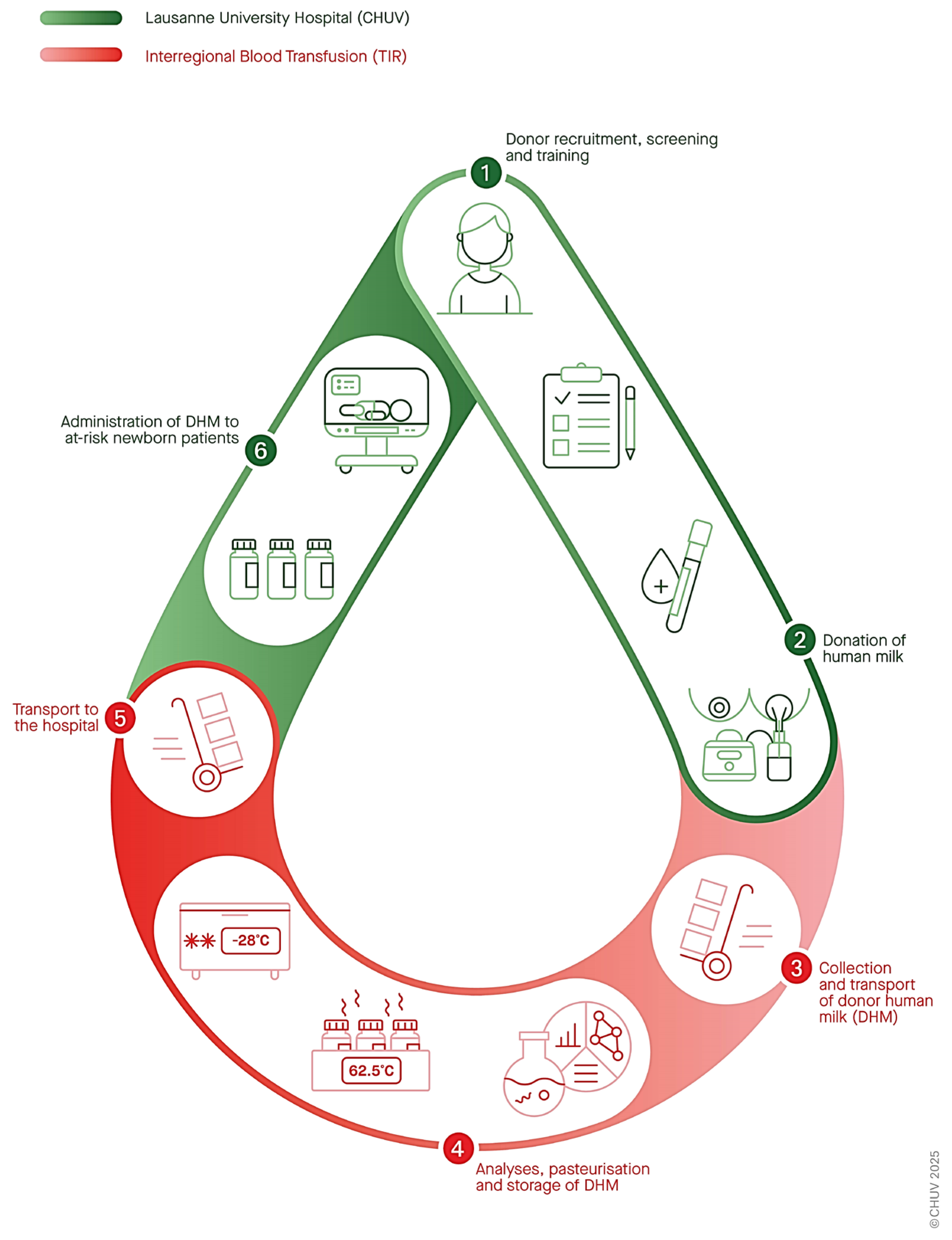

- Donor recruitment, screening, and training.

- DHM collection and transport.

- Processing (including multi-donor pooling, microbiological analyses, and Holder pasteurization).

- Storage (cold room at −30 °C for up to 6 months after pasteurization).

- Transport to the hospital (based on clinical needs).

- Administration to at-risk hospitalized neonates (following medical prescription and parental consent).

- Full process traceability from donors to recipients while maintaining anonymity.

3.3. Phase 3: Launch–2022

- -

- Launch: In May 2022, after more than two years of strategic planning by the interdisciplinary team, the “CHUV Lactarium” was launched as a nonprofit, regional, “human milk bank–blood bank”. Integrated into neonatal care, it complemented the hospital’s nutrition and lactation support program. Funded by the government as a public health service, the initiative was well received by healthcare professionals, the public, and the media.

3.4. Phase 4: Operation and Monitoring—Ongoing Since 2022

- -

- CHUV and TIR have collaborated closely to streamline their processes. Members from both institutions participate in (a) an operational team; (b) several advisory expert groups that provide periodic guidance on specific topics such as microbiology, quality management and bioethics; and (c) a monitoring committee that conducts biannual reviews to ensure oversight and enhance program strategies.At the core of this coordination, the operational team meets weekly to monitor and assess key performance indicators. DHM volumes are adjusted according to patients’ real-time needs to prevent shortages or waste. This is achieved through incremental donor recruitment strategies and a flexible schedule in DHM pasteurization. When necessary, DHM allocation follows a pragmatic, evidence-based prioritization system based on clinical benefit, adapted from French guidelines and other established practices [16,38]. Accordingly, three levels of prioritization are defined:

- Level 1: In the event of a crisis or shortage, DHM provision would be restricted to the most vulnerable patients, i.e., those under 28 weeks postmenstrual age or weighing less than 1000g. Such restrictions have not been required to date.

- Level 2: The standard target level, including all infants under 32 weeks postmenstrual age or weighing less than 1500 g.

- Level 3: In the case of a temporary surplus, DHM may be administered to patients up to 34 weeks postmenstrual age or weighing up to 1800 g.

- -

- Monitoring and main achievements: From May 2022 to December 2024, the CHUV Lactarium met 100% of the needs for DHM for eligible patients, resulting in a positive clinical impact. Key indicators and achievements are listed in Table 1.

4. Discussion

4.1. Barriers and Facilitators

- Interprofessional and interdisciplinary collaboration that facilitated effective coordination among partners and institutions.

- Leveraging complementary expertise, infrastructure, and resources.

- Pre-existing hospital-based breastfeeding support program, which served as a foundational “pillar”.

- Systematic preparation and phased project management.

- Robust joint leadership and endorsement from public health authorities.

- National and international HMB networking and mentorship.

- Active community outreach and media involvement.

4.2. Strengths and Interest

- Case studies of novel HMB implementation: Global HMB expansion is crucial to addressing disparities in accessing human milk [14,25]. Sharing and disseminating practical examples and analysis of scalable, efficient HMB implementations can support the scaling-up of HMBs across diverse resource settings [42,43,44,45].

- Transferability: Although Switzerland is a small, high-income country, its complex, decentralized healthcare system and lack of national coordination in human milk banking reflect challenges common to many settings. Its multilingual, multicultural context further exemplifies these difficulties. For instance, in Europe, despite over 280 operational HMBs and established guidelines [15], only 9 of 26 countries legally regulate DHM [46], while, in another survey, 7 of 10 lack reimbursement frameworks [47].

- Leveraging established quality frameworks: Integrating human milk banking within established blood and tissue donation frameworks facilitates the adoption of rigorous strategies, such as quality assurance and good manufacturing practices, thereby promoting high standards of quality and safety. This approach is likely to gain importance under forthcoming European regulations classifying human milk as a substance of human origin (SoHO) [23,48].

- Enhancing breastfeeding: Unlike other MPHOs, HMBs can reduce the demand for DHM by promoting breastfeeding and increasing MOM supply [28,49]. The establishment of HMB should reinforce, rather than replace, existing breastfeeding support strategies, viewing DHM as a bridge rather than a substitute for MOM. Therefore, integrated, patient-centered models that combine the provision of DHM with lactation support are more effective than independent, product-based approaches and are strongly recommended [14,50]. The CHUV Lactarium is among the first “human milk bank–blood bank” models embedded in neonatal care, infant nutrition, and lactation support.

- Efficacy and equity: This case study demonstrates that, even in a single-center setting, coordinated efforts and proactive planning for DHM needs can ensure consistent, efficient, and equitable distribution. This approach fully meets clinical demand without creating shortages or excess. Protocols were established to prioritize the most vulnerable infants during crises, though they have not yet needed to be activated [16,38,51].

- Sustainability issues: According to a recent review, MPHO-inspired HMB operational models help strengthen safety, enhance quality, and support regulatory-driven sustainability [28]. Additionally, DHM offers potential environmental benefits by supporting breastfeeding [20] and reducing formula use [52], aligning with the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals [53]. Although processing DHM can be considered an energy-intensive process, leveraging existing infrastructure (e.g., cold chambers, transportation, and IT systems) can help mitigate both financial and environmental costs. Currently, the CHUV Lactarium is pursuing actions to reduce plastic waste and collaborating in research to improve the sustainability of human milk donations [37].

- Creation of the Lacto-biobank: In compliance with Swiss Biobanking Platform standards, the CHUV Lactarium has operated a lacto-biobank since 2023 to redirect human milk unsuitable for clinical use towards research and development [39]. This strategy also helps to reduce donor frustration associated with milk rejection and enables the management of surplus donation proposals, which currently exceed patient DHM needs [54].

4.3. Limitations and Areas for Improvement and Development

- Discarding rate: Currently, approximately 20% of collected milk is discarded due to microbiological non-compliance, primarily identified from pre-pasteurization cultures of internal donors (i.e., mothers of hospitalized infants). Although this falls within the reported 7–27% range [55], it underscores challenges related to hygiene standards, testing protocols and microbiological criteria [56]. The operational team is actively addressing these issues to enhance process efficiency.

- DHM volumes and scope for expansion: The CHUV Lactarium currently supplies 250–300 L of DHM annually to a single center, ranking among the highest DHM volumes in Switzerland. Nevertheless, the DHM distribution volume and capacities remain limited compared to other, more centralized systems, such as in France or Canada. Scaling up production could improve cost-efficiency and help absorb the surplus of donations proposals, many of which are currently declined or redirected to the lacto-biobank. The CHUV Lactarium is therefore actively exploring options to expand its DHM distribution network.

- Financial issues: Although DHM provision is more expensive than formula [57,58], it has been shown to be cost-effective and even cost-saving, mainly by reducing the incidence of NEC and the associated healthcare costs [59]. However, the lack of financial models remains a common barrier to scale-up HMBs. Processing DHM as a MPHO may likely incur higher short-term costs than food-grade handling [50]. However, optimizing resources and increasing distribution volumes may help improve cost efficiency. A context specific medico-economic analysis, including long-term outcomes, is planned to support sustainable financial planning of the model.

- Other perspectives and challenges: As a recent HMB, the CHUV Lactarium needs to consolidate its expertise while adapting to numerous current and future developments in human milk science, processes, technologies, ethics, and regulations [47].

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ADLF | French human milk banks association (Association des Lactariums de France) |

| CHUV | Lausanne University Hospital (Centre Hospitalier Universitaire Vaudois) |

| DHM | donor human milk |

| DSAS | Department of Health and Social Action |

| EMBA | European Milk Banking Association |

| GAMBA | Global Alliance of Milk Banks and Associations |

| GMP | good manufacturing practices |

| HMB | human milk bank |

| MOM | mother’s own milk |

| MPHO | medical product of human origin |

| NEC | necrotizing enterocolitis |

| SoHO | substance of human origin |

| SOP | standard operating procedure |

| MNDS | Swiss Minimal Neonatal Data Set |

| TIR | Interregional Blood Transfusion of the Swiss Red Cross (Transfusion InterRégionale) |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

References

- Smilowitz, J.T.; Allen, L.H.; Dallas, D.C.; McManaman, J.; Raiten, D.J.; Rozga, M.; Sela, D.A.; Seppo, A.; Williams, J.E.; Young, B.E.; et al. Ecologies, Synergies, and Biological Systems Shaping Human Milk Composition-a Report from “Breastmilk Ecology: Genesis of Infant Nutrition (BEGIN)” Working Group 2. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2023, 117 (Suppl. 1), S28–S42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Victora, C.G.; Bahl, R.; Barros, A.J.D.; França, G.V.A.; Horton, S.; Krasevec, J.; Murch, S.; Sankar, M.J.; Walker, N.; Rollins, N.C. Breastfeeding in the 21st Century: Epidemiology, Mechanisms, and Lifelong Effect. Lancet 2016, 387, 475–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meek, J.Y.; Noble, L. Technical Report: Breastfeeding and the Use of Human Milk. Pediatrics 2022, 150, e2022057989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, K. Breastfeeding: A Smart Investment in People and in Economies. Lancet 2016, 387, 416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joffe, N.; Webster, F.; Shenker, N. Support for Breastfeeding Is an Environmental Imperative. BMJ 2019, 367, l5646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, J.; Tonkin, E.; Damarell, R.A.; McPhee, A.J.; Suganuma, M.; Suganuma, H.; Middleton, P.F.; Makrides, M.; Collins, C.T. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Human Milk Feeding and Morbidity in Very Low Birth Weight Infants. Nutrients 2018, 10, 707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, M.G.; Stellwagen, L.M.; Noble, L.; Kim, J.H.; Poindexter, B.B.; Puopolo, K.M.; Section on Breastfeeding, Committee on Nutrition, Committee on Fetus and Newborn. Promoting Human Milk and Breastfeeding for the Very Low Birth Weight Infant. Pediatrics 2021, 148, e2021054272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonnet, C.; Blondel, B.; Piedvache, A.; Wilson, E.; Bonamy, A.-K.E.; Gortner, L.; Rodrigues, C.; van Heijst, A.; Draper, E.S.; Cuttini, M.; et al. Low Breastfeeding Continuation to 6 Months for Very Preterm Infants: A European Multiregional Cohort Study. Matern. Child. Nutr. 2019, 15, e12657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonet, M.; Blondel, B.; Agostino, R.; Combier, E.; Maier, R.F.; Cuttini, M.; Khoshnood, B.; Zeitlin, J.; MOSAIC research group. Variations in Breastfeeding Rates for Very Preterm Infants between Regions and Neonatal Units in Europe: Results from the MOSAIC Cohort. Arch. Dis. Child. Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2011, 96, F450–F452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heller, N.; Rüdiger, M.; Hoffmeister, V.; Mense, L. Mother’s Own Milk Feeding in Preterm Newborns Admitted to the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit or Special-Care Nursery: Obstacles, Interventions, Risk Calculation. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2021, 18, 4140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer Fumeaux, C.J.; Fletgen Richard, C.; Goncalves Pereira Pinto, D.; Stadelmann, C.; Avignon, V.; Vial, Y.; Tolsa, J.-F.; Ambresin, A.-E.; Armengaud, J.-B.; Castaneda, M.; et al. Novelties 2016 in pediatrics. Rev. Med. Suisse 2017, 13, 92–95. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- WHO. WHO Recommendations for Care of the Preterm or Low-Birth-Weight Infant; WHO Guidelines Approved by the Guidelines Review Committee; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022; Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240058262 (accessed on 16 May 2025).

- Embleton, N.D.; Jennifer Moltu, S.; Lapillonne, A.; van den Akker, C.H.P.; Carnielli, V.; Fusch, C.; Gerasimidis, K.; van Goudoever, J.B.; Haiden, N.; Iacobelli, S.; et al. Enteral Nutrition in Preterm Infants (2022): A Position Paper From the ESPGHAN Committee on Nutrition and Invited Experts. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2023, 76, 248–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Israel-Ballard, K.; LaRose, E.; Mansen, K. The Global Status of Human Milk Banking. Matern. Child. Nutr. 2024, 20 (Suppl. 4), e13592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moro, G.E.; Billeaud, C.; Rachel, B.; Calvo, J.; Cavallarin, L.; Christen, L.; Escuder-Vieco, D.; Gaya, A.; Lembo, D.; Wesolowska, A.; et al. Processing of Donor Human Milk: Update and Recommendations From the European Milk Bank Association (EMBA). Front. Pediatr. 2019, 7, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Unger, S.L.; O’Connor, D.L. Review of Current Best Practices for Human Milk Banking. Matern. Child. Nutr. 2024, 20 (Suppl. 4), e13657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quigley, M.; Embleton, N.D.; Meader, N.; McGuire, W. Donor Human Milk for Preventing Necrotising Enterocolitis in Very Preterm or Very Low-Birthweight Infants. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2024, 9, CD002971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meier, P.; Patel, A.; Esquerra-Zwiers, A. Donor Human Milk Update: Evidence, Mechanisms, and Priorities for Research and Practice. J. Pediatr. 2017, 180, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckle, A.; Taylor, C. Cost and Cost-Effectiveness of Donor Human Milk to Prevent Necrotizing Enterocolitis: Systematic Review. Breastfeed. Med. 2017, 12, 528–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, T.; Nair, H.; Simpson, J.; Embleton, N. Use of Donor Human Milk and Maternal Breastfeeding Rates: A Systematic Review. J. Hum. Lact. 2016, 32, 212–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, M.G.K.; Burnham, L.; Mao, W.; Philipp, B.L.; Merewood, A. Implementation of a Donor Milk Program Is Associated with Greater Consumption of Mothers’ Own Milk among VLBW Infants in a US, Level 3 NICU. J. Hum. Lact. 2016, 32, 221–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Principles on the Donation and Management of Blood, Blood Components and Other Medical Products of Human Origin: Report by the Secretariat. 2017. Available online: https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/274793 (accessed on 16 May 2025).

- European Union. Regulation (EU) 2024/1938 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 13 June 2024 on Standards of Quality and Safety for Substances of Human Origin Intended for Human Application and Repealing Directives 2002/98/EC and 2004/23/EC (Text with EEA Relevance). 2024. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32024R1938 (accessed on 16 May 2025).

- Toney-Noland, C.; Cohen, R.S.; Joe, L.; Kan, P.; Lee, H.C. Factors Associated with Inequities in Donor Milk Bank Access Among Different Hospitals. Breastfeed. Med. 2024, 19, 964–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Israel-Ballard, K.; Cohen, J.; Mansen, K.; Parker, M.; Engmann, C.; Kelley, M.; Oxford-PATH Human Milk Working Group. Call to Action for Equitable Access to Human Milk for Vulnerable Infants. Lancet Glob. Health 2019, 7, e1484–e1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, M.T.; Grummer-Strawn, L.; Maryuningsih, Y.; Biller-Andorno, N. Human Milk Banks: A Need for Further Evidence and Guidance. Lancet Glob. Health 2021, 9, e104–e105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Rourke, J.; Long, S.; LePage, N.L.; Waxman, D.A. How Do I Create a Partnership between a Blood Bank and a Milk Bank to Provide Safe, Pasteurized Human Milk to Infants? Transfusion 2021, 61, 350–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herson, M.; Weaver, G. A Comparative Review of Human Milk Banking and National Tissue Banking Programs. Matern. Child. Nutr. 2024, 20 (Suppl. 4), e13584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shenker, N.; Linden, J.; Wang, B.; Mackenzie, C.; Hildebrandt, A.P.; Spears, J.; Davis, D.; Nangia, S.; Weaver, G. Comparison between the For-Profit Human Milk Industry and Nonprofit Human Milk Banking: Time for Regulation? Matern. Child. Nutr. 2024, 20, e13570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusi, H.C.; Grummer-Strawn, L.; Perrin, M.T.; Risling, T.; Brockway, M.L. Conceptualizing the Commercialization of Human Milk: A Concept Analysis. J. Hum. Lact. 2024, 40, 392–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weaver, G.; Chatzixiros, E.; Biller-Andorno, N.; Grummer-Strawn, L.; the Human Milk Banking Consultative Working Group. International Expert Meeting on the Donation and Use of Human Milk: Brief Report. Matern. Child. Nutr. 2024; 20, (Suppl. 4), e13550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klotz, D.; Jansen, S.; Glanzmann, R.; Haiden, N.; Fuchs, H.; Gebauer, C. Donor Human Milk Programs in German, Austrian and Swiss Neonatal Units—Findings from an International Survey. BMC Pediatr. 2020, 20, 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barin, J.; Quack Lötscher, K. The MILK GAP—Contextualizing Human Milk Banking and Milk Sharing Practices and Perceptions in Switzerland. 2018. Available online: https://www.stillfoerderung.ch/logicio/client/stillen/archive/document/Publikationen/Final_Milk_Gap_Report_27.08.2018_klein.pdf (accessed on 16 May 2025).

- Arbeitsgruppe «Frauenmilchbanken Schweiz». Leitlinie Zur Organisation Und Arbeitsweise Einer Frauenmilchbank in Der Schweiz, 2020. Available online: https://www.neonet.ch/application/files/7816/2460/3693/Leitlinie_Frauenmilchbanken_CH_2_Auflage_Finalc_Screen.pdf (accessed on 16 May 2025).

- Confédération Suisse, Office Fédéral de la Statistique. Mortalité Infantile et Santé des Nouveau-Nés en 2023—GNP Diffusion. 2024. Available online: https://www.bfs.admin.ch/bfs/fr/home.html (accessed on 16 May 2025).

- Le Parlement Suisse. Dangers de l’Échange Direct de Lait Maternel. Interpellation et Avis du Conseil Fédéral. Available online: https://www.parlament.ch/fr/ratsbetrieb/suche-curia-vista/geschaeft?AffairId=20193674 (accessed on 16 May 2025).

- Kaech, C.; Kilgour, C.; Fischer Fumeaux, C.J.; de Labrusse, C.; Humphrey, T. Factors That Influence the Sustainability of Human Milk Donation to Milk Banks: A Systematic Review. Nutrients 2022, 14, 5253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haute Autorité de santé. Indications Priorisées du lait de Lactarium Issu de don Anonyme, Recommandation de Bonne Pratique. 2021. Available online: https://www.has-sante.fr/jcms/p_3266755/fr/indications-priorisees-du-lait-de-lactarium-issu-de-don-anonyme (accessed on 16 May 2025).

- Swiss Biobanking Platform (SBP). Swiss Biobanking Platform—SBP Is the Leading National Research Infrastructure for Biobanking Activities. Available online: https://swissbiobanking.ch/ (accessed on 16 May 2025).

- Israel-Ballard, K. Strengthening Systems to Ensure All Infants Receive Human Milk: Integrating Human Milk Banking into Newborn Care and Nutrition Programming. Breastfeed. Med. 2018, 13, 524–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dratva, J.; Gross, K.; Späth, A.; Zemp Stutz, E. SWIFS—Swiss Infant Feeding Study A National Study on Infant Feeding and Health in the Child’s First Year. Executive Summary. Available online: https://www.swisstph.ch/en/projects/swifs/ (accessed on 15 December 2024).

- Tyebally Fang, M.; Chatzixiros, E.; Grummer-Strawn, L.; Engmann, C.; Israel-Ballard, K.; Mansen, K.; O’Connor, D.L.; Unger, S.; Herson, M.; Weaver, G.; et al. Developing Global Guidance on Human Milk Banking. Bull. World Health Organ. 2021, 99, 892–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mansen, K.; Nguyen, T.T.; Nguyen, N.Q.; Do, C.T.; Tran, H.T.; Nguyen, N.T.; Mathisen, R.; Nguyen, V.D.; Ngo, Y.T.K.; Israel-Ballard, K. Strengthening Newborn Nutrition Through Establishment of the First Human Milk Bank in Vietnam. J. Hum. Lact. 2021, 37, 76–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramachandran, K.; Dahlui, M.; Nik Farid, N.D. Motivators and Barriers to the Acceptability of a Human Milk Bank among Malaysians. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0299308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilunda, C.; Israel-Ballard, K.; Wanjohi, M.; Lang’at, N.; Mansen, K.; Waiyego, M.; Kibore, M.; Kamande, E.; Zerfu, T.; Kithua, A.; et al. Potential Effectiveness of Integrating Human Milk Banking and Lactation Support on Neonatal Outcomes at Pumwani Maternity Hospital, Kenya. Matern. Child. Nutr. 2024, 20, e13594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klotz, D.; Wesołowska, A.; Bertino, E.; Moro, G.E.; Picaud, J.-C.; Gayà, A.; Weaver, G. The Legislative Framework of Donor Human Milk and Human Milk Banking in Europe. Matern. Child. Nutr. 2022, 18, e13310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kontopodi, E.; Arslanoglu, S.; Bernatowicz-Lojko, U.; Bertino, E.; Bettinelli, M.E.; Buffin, R.; Cassidy, T.; van Elburg, R.M.; Gebauer, C.; Grovslien, A.; et al. “Donor Milk Banking: Improving the Future”. A Survey on the Operation of the European Donor Human Milk Banks. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0256435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weaver, G.; Bertino, E.; Gebauer, C.; Grovslien, A.; Mileusnic-Milenovic, R.; Arslanoglu, S.; Barnett, D.; Boquien, C.-Y.; Buffin, R.; Gaya, A.; et al. Recommendations for the Establishment and Operation of Human Milk Banks in Europe: A Consensus Statement from the European Milk Bank Association (EMBA). Front. Pediatr. 2019, 7, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dymek, N.G.; Jaschke, J.; Stirner, A.K.; Schwab, I.; Ohnhäuser, T.; Wiesen, D.; Dresbach, T.; Scholten, N.; Köberlein-Neu, J.; Neo-MILK Consortium. Structured Lactation Support for Mothers of Very Low Birthweight Preterm Infants and Establishment of Human Donor Milk Banks in German NICUs (Neo-MILK): Protocol for a Hybrid Type 1 Effectiveness-Implementation Cluster-Randomised Controlled Trial. BMJ Open 2025, 15, e084746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PATH. Strengthening Human Milk Banking—A Resource Toolkit for Establishing and Integrating Human Milk Banks. Available online: https://www.path.org/programs/maternal-newborn-child-health-and-nutrition/strengthening-human-milk-banking-resource-toolkit/ (accessed on 16 May 2025).

- Shenker, N.; Staff, M.; Vickers, A.; Aprigio, J.; Tiwari, S.; Nangia, S.; Sachdeva, R.C.; Clifford, V.; Coutsoudis, A.; Reimers, P.; et al. Virtual Collaborative Network of Milk Banks and Associations. Maintaining Human Milk Bank Services throughout the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Global Response. Matern. Child. Nutr. 2021, 17, e13131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pope, D.H.; Karlsson, J.O.; Baker, P.; McCoy, D. Examining the Environmental Impacts of the Dairy and Baby Food Industries: Are First-Food Systems a Crucial Missing Part of the Healthy and Sustainable Food Systems Agenda Now Underway? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 12678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Sustainable Development. Breastfeeding is “Smartest Investment” Families, Communities and Countries Can Make. UN News Centre. 2017. Available online: https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/blog/2017/08/breastfeeding-is-smartest-investment-families-communities-and-countries-can-make-un/ (accessed on 16 May 2025).

- Brown, A.; Griffiths, C.; Jones, S.; Weaver, G.; Shenker, N. Disparities in Being Able to Donate Human Milk Impacts upon Maternal Wellbeing: Lessons for Scaling up Milk Bank Service Provision. Matern. Child. Nutr. 2024, 20, e13699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreiner, C.; Müller, A.; Dresbach, T. Microbiological Screening of Donor Human Milk. Breastfeed. Med. 2023, 18, 901–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clifford, V.; Klein, L.D.; Sulfaro, C.; Karalis, T.; Hoad, V.; Gosbell, I.; Pink, J. What Are Optimal Bacteriological Screening Test Cut-Offs for Pasteurized Donor Human Milk Intended for Feeding Preterm Infants? J. Hum. Lact. 2021, 37, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mistry, H.; Weaver, G.; Shenker, N. Cost of Operating a Human Milk Bank in the UK: A Microcosting Analysis. Arch. Dis. Child.-Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2025, 110, 133–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fengler, J.; Heckmann, M.; Lange, A.; Kramer, A.; Flessa, S. Cost Analysis Showed That Feeding Preterm Infants with Donor Human Milk Was Significantly More Expensive than Mother’s Milk or Formula. Acta Paediatr. 2020, 109, 959–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanganeh, M.; Jordan, M.; Mistry, H. A Systematic Review of Economic Evaluations for Donor Human Milk versus Standard Feeding in Infants. Matern. Child. Nutr. 2021, 17, e13151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Examples of Indicators/Achievements | |

|---|---|

| Donor recruitment and human milk collection |

|

| DHM patients delivery |

|

| Nutritional and clinical outcomes * |

|

| Education and training |

|

| Collaboration between CHUV and TIR |

|

| Human milk and donation awareness |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Barin, J.; Touati, J.; Martin, A.; Fletgen Richard, C.; Jox, R.J.; Fontana, S.; Legardeur, H.; Amiguet, N.; Henriot, I.; Kaech, C.; et al. Bridging the Milk Gap: Integrating a Human Milk Bank–Blood Bank Model to Reinforce Lactation Support and Neonatal Care. Nutrients 2025, 17, 1765. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17111765

Barin J, Touati J, Martin A, Fletgen Richard C, Jox RJ, Fontana S, Legardeur H, Amiguet N, Henriot I, Kaech C, et al. Bridging the Milk Gap: Integrating a Human Milk Bank–Blood Bank Model to Reinforce Lactation Support and Neonatal Care. Nutrients. 2025; 17(11):1765. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17111765

Chicago/Turabian StyleBarin, Jacqueline, Jeremy Touati, Agathe Martin, Carole Fletgen Richard, Ralf J. Jox, Stefano Fontana, Hélène Legardeur, Nathalie Amiguet, Isabelle Henriot, Christelle Kaech, and et al. 2025. "Bridging the Milk Gap: Integrating a Human Milk Bank–Blood Bank Model to Reinforce Lactation Support and Neonatal Care" Nutrients 17, no. 11: 1765. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17111765

APA StyleBarin, J., Touati, J., Martin, A., Fletgen Richard, C., Jox, R. J., Fontana, S., Legardeur, H., Amiguet, N., Henriot, I., Kaech, C., Belat, A., Tolsa, J.-F., Prudent, M., & Fischer Fumeaux, C. J. (2025). Bridging the Milk Gap: Integrating a Human Milk Bank–Blood Bank Model to Reinforce Lactation Support and Neonatal Care. Nutrients, 17(11), 1765. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17111765