The Practice of Weight Loss in Combat Sports Athletes: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Registration of Systematic Review Protocol

2.2. Information Sources and Search Strategy

2.3. Eligibility Criteria

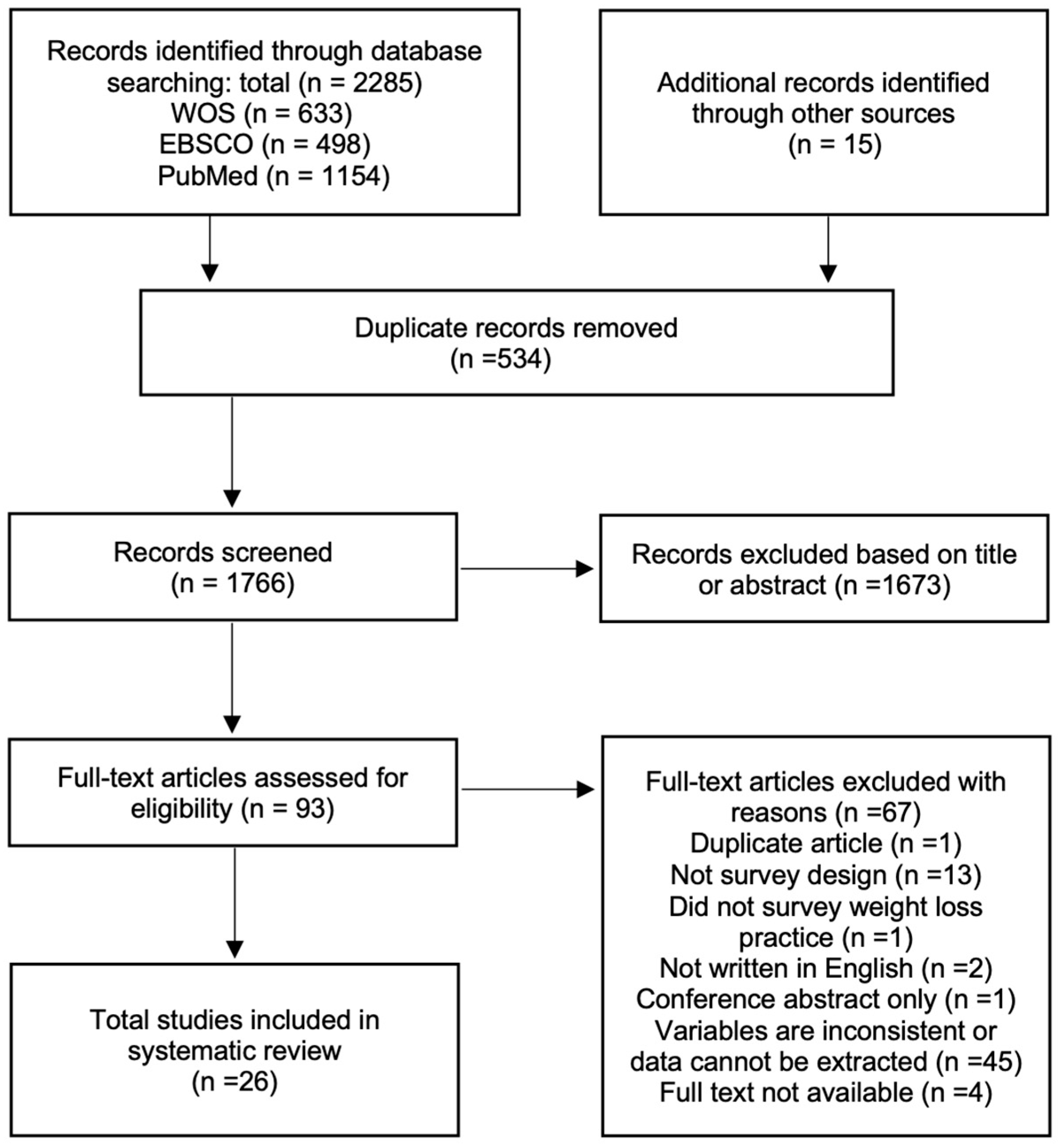

2.4. Study Selection

2.5. Data Collection Process and Data Items

2.6. Study Risk of Bias Assessment

3. Results

3.1. Study Selection

3.2. Study and Participant Characteristics

3.3. Study Risk of Bias Assessment

3.4. Prevalence of WL

3.5. Weight History

3.6. WL Methods Used

3.7. Person Who Influenced Their WL Practice

4. Discussion

4.1. Prevalence of WL

4.2. Weight History

4.3. WL Methods Used

4.4. Person Who Influenced Their WL Practice

5. Conclusions

6. Practical Application

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Franchini, E.; Brito, C.J.; Artioli, G.G. Weight loss in combat sports: Physiological, psychological and performance effects. J. Int. Soc. Sports Nutr. 2012, 9, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baranauskas, M.; Kupčiūnaitė, I.; Stukas, R. The Association between Rapid Weight Loss and Body Composition in Elite Combat Sports Athletes. Healthcare 2022, 10, 665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kons, R.L.; Gheller, R.G.; Costa, F.E.; Detanico, D. Rapid weight loss in visually impaired judo athletes: Prevalence, magnitude, and methods. Br. J. Vis. Impair. 2022, 40, 255–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranisavljev, M.; Kuzmanovic, J.; Todorovic, N.; Roklicer, R.; Dokmanac, M.; Baic, M.; Stajer, V.; Ostojic, S.M.; Drid, P. Rapid Weight Loss Practices in Grapplers Competing in Combat Sports. Front. Physiol. 2022, 13, 842992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roklicer, R.; Rossi, C.; Bianco, A.; Stajer, V.; Ranisavljev, M.; Todorovic, N.; Manojlovic, M.; Gilic, B.; Trivic, T.; Drid, P. Prevalence of rapid weight loss in Olympic style wrestlers. J. Int. Soc. Sports Nutr. 2022, 19, 593–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pélissier, L.; Ennequin, G.; Bagot, S.; Pereira, B.; Lachèze, T.; Duclos, M.; Thivel, D.; Miles-Chan, J.; Isacco, L. Lightest weight-class athletes are at higher risk of weight regain: Results from the French-Rapid Weight Loss Questionnaire. Physician Sportsmed. 2023, 51, 144–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vasconcelos, B.B.; Guedes, J.B.; Del Vecchio, F.B. Prevalence, magnitude, and methods of rapid weight loss in national level Wushu Sanda athletes. Sci. Sports 2023, 39, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degoutte, F.; Jouanel, P.; Bègue, R.J.; Colombier, M.; Lac, G.; Pequignot, J.M.; Filaire, E. Food restriction, performance, biochemical, psychological, and endocrine changes in judo athletes. Int. J. Sports Med. 2006, 27, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakicevic, N.; Paoli, A.; Roklicer, R.; Trivic, T.; Korovljev, D.; Ostojic, S.M.; Proia, P.; Bianco, A.; Drid, P. Effects of Rapid Weight Loss on Kidney Function in Combat Sport Athletes. Medicina 2021, 57, 551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.H.; Heine, O.; Pauly, S.; Kim, P.; Bloch, W.; Mester, J.; Grau, M. Rapid rather than gradual weight reduction impairs hemorheological parameters of Taekwondo athletes through reduction in RBC-NOS activation. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0123767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crighton, B.; Close, G.L.; Morton, J.P. Alarming weight cutting behaviours in mixed martial arts: A cause for concern and a call for action. Br. J. Sports Med. 2016, 50, 446–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reale, R.; Slater, G.; Burke, L.M. Weight Management Practices of Australian Olympic Combat Sport Athletes. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 2018, 13, 459–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos-Junior, R.B.; Utter, A.C.; McAnulty, S.R.; Bittencourt Bernardi, B.R.; Buzzachera, C.F.; Franchini, E.; Souza-Junior, T.P. Weight loss behaviors in Brazilian mixed martial arts athletes. Sport Sci. Health 2020, 16, 117–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woods, E.R.; Wilson, C.D.; Masland, R.P., Jr. Weight control methods in high school wrestlers. J. Adolesc. Health Care 1988, 9, 394–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drid, P.; Figlioli, F.; Lakicevic, N.; Gentile, A.; Stajer, V.; Raskovic, B.; Vojvodic, N.; Roklicer, R.; Trivic, T.; Tabakov, S.; et al. Patterns of rapid weight loss in elite sambo athletes. BMC Sports Sci. Med. Rehabil. 2021, 13, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dugonjić, B.; Krstulović, S.; Kuvačić, G. Rapid Weight Loss Practices in Elite Kickboxers. Int. J. Sport Nutr. Exerc. Metab. 2019, 29, 583–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oppliger, R.A.; Steen, S.A.N.; Scott, J.R. Weight loss practices of college wrestlers. Int. J. Sport Nutr. Exerc. Metab. 2003, 13, 29–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amatori, S.; Barley, O.R.; Gobbi, E.; Vergoni, D.; Carraro, A.; Baldari, C.; Guidetti, L.; Rocchi, M.B.L.; Perroni, F.; Sisti, D. Factors Influencing Weight Loss Practices in Italian Boxers: A Cluster Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva Santos, J.F.; Takito, M.Y.; Artioli, G.G.; Franchini, E. Weight loss practices in Taekwondo athletes of different competitive levels. J. Exerc. Rehabil. 2016, 12, 202–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artioli, G.G.; Gualano, B.; Franchini, E.; Scagliusi, F.B.; Takesian, M.; Fuchs, M.; Lancha, A.H. Prevalence, Magnitude, and Methods of Rapid Weight Loss among Judo Competitors. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2010, 42, 436–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marquart, L.F.; Sobal, J. Weight loss beliefs, practices and support systems for high school wrestlers. J. Adolesc. Health 1994, 15, 410–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oppliger, R.A.; Landry, G.L.; Foster, S.W.; Lambrecht, A.C. Weight-cutting practices of high school wrestlers. Clin. J. Sport Med. 1998, 8, 26–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarikaya, M.; ÖKmen, M.Ş.; KilinÇArslan, G.; Bayrakdar, A. Investigation of Weight Loss Methods of Wrestlers Fighting in Different Styles and Categories During the Competition Period. Turk. J. Sport Exerc./Türk Spor Egzersiz Derg. 2023, 25, 35–41. [Google Scholar]

- Seyhan, S. Evaluation of the Rapid Weight Loss Practices of Taekwondo Athletes and Their Effects. J. Educ. Train. Stud. 2018, 6, 213–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, K.A.; Naughton, R.J.; Langan-Evans, C.; Lewis, K. “Horrible-But Worth It”: Exploring Weight Cutting Practices, Eating Behaviors, and Experiences of Competitive Female Taekwon-Do Athletes. A Mixed Methods Study. J. Clin. Sport Psychol. 2022, 18, 150–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Štangar, M.; Štangar, A.; Shtyrba, V.; Cigić, B.; Benedik, E. Rapid weight loss among elite-level judo athletes: Methods and nutrition in relation to competition performance. J. Int. Soc. Sports Nutr. 2022, 19, 380–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stiene, H.A. A comparison of weight-loss methods in high school and collegiate wrestlers. Clin. J. Sport Med. 1993, 3, 95–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uddin, N.; Waldron, M.; Patterson, S.D.; Winter, S.; Tallent, J. A Survey of Combat Athletes’ Rapid Weight Loss Practices and Evaluation of the Relationship With Concussion Symptom Recall. Clin. J. Sport Med. 2022, 32, 580–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viveiros, L.; Moreira, A.; Zourdos, M.C.; Aoki, M.S.; Capitani, C.D. Pattern of Weight Loss of Young Female and Male Wrestlers. J. Strength. Cond. Res. 2015, 29, 3149–3155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, P.B.; Madrigal, L.A.; Burnfield, J.M. Weight control practices of Division I National Collegiate Athletic Association athletes. Physician Sportsmed. 2016, 44, 170–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wroble, R.R.; Moxley, D.P. Weight loss patterns and success rates in high school wrestlers. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 1998, 30, 625–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yagmur, R.; Isik, O.; Kilic, Y.; Dogan, I. Weight Loss Methods and Effects on the Elite Cadet Greco-Roman Wrestlers. JTRM Kinesiol. 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Artioli, G.G.; Scagliusi, F.; Kashiwagura, D.; Franchini, E.; Gualano, B.; Junior, A.L. Development, validity and reliability of a questionnaire designed to evaluate rapid weight loss patterns in judo players. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2010, 20, e177–e187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berkovich, B.-E.; Eliakim, A.; Nemet, D.; Stark, A.H.; Sinai, T. Rapid Weight Loss Among Adolescents Participating In Competitive Judo. Int. J. Sport Nutr. Exerc. Metab. 2016, 26, 276–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brito, C.J.; Castro Martins Roas, A.F.; Souza Brito, I.S.; Bouzas Marins, J.C.; Cordova, C.; Franchini, E. Methods of Body-Mass Reduction by Combat Sport Athletes. Int. J. Sport Nutr. Exerc. Metab. 2012, 22, 89–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castor-Praga, C.; Lopez-Walle, J.M.; Sanchez-Lopez, J. Multilevel Evaluation of Rapid Weight Loss in Wrestling and Taekwondo. Front. Sociol. 2021, 6, 637671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheah, W.L.; Bo, M.S.; Kana, W.A.; Tourisz, N.I.B.M.; Ishak, M.A.H.B.; Yogeswaran, M. Prevalence of Rapid Weight Loss Practices and Their Profiles Among Non-Elite Combat Athletes in Kuching, East Malaysia. Pol. J. Sport Tour. 2019, 26, 14–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connor, J.; Egan, B. Prevalence, Magnitude and Methods of Rapid Weight Loss Reported by Male Mixed Martial Arts Athletes in Ireland. Sports 2019, 7, 206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figlioli, F.; Bianco, A.; Thomas, E.; Stajer, V.; Korovljev, D.; Trivic, T.; Maksimovic, N.; Drid, P. Rapid Weight Loss Habits before a Competition in Sambo Athletes. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillier, M.; Sutton, L.; James, L.; Mojtahedi, D.; Keay, N.; Hind, K. High Prevalence and Magnitude of Rapid Weight Loss in Mixed Martial Arts Athletes. Int. J. Sport Nutr. Exerc. Metab. 2019, 29, 512–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, C.; Park, K.J. Injuries and Rapid Weight Loss in Elite Adolescent Taekwondo Athletes: A Korean Prospective Cohort Study. Phys. Med. Rehabil. Kurortmed. 2021, 31, 184–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kons, R.L.; Da Silva Athayde, M.S.; Follmer, B.; Detanico, D. Methods and Magnitudes of Rapid Weight Loss in Judo Athletes Over Pre-Competition Periods. Hum. Mov. 2017, 18, 49–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malliaropoulos, N.; Rachid, S.; Korakakis, V.; Fraser, S.; Bikos, G.; Maffulli, N.; Angioi, M. Prevalence, techniques and knowledge of rapid weight loss amongst adult british judo athletes: A questionnaire based study. Muscles Ligaments Tendons J. 2018, 7, 459–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Todorović, N.; Ranisavljev, M.; Tapavički, B.; Zubnar, A.; Kuzmanović, J.; Štajer, V.; Sekulić, D.; Veršić, Š.; Tabakov, S.; Drid, P. Principles of Rapid Weight Loss in Female Sambo Athletes. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 11356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- White, T.; Kirk, C. Pre-competition body mass loss characteristics of Brazilian jiu-jitsu competitors in the United Kingdom. Nutr. Health 2021, 27, 387–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yarar, H.; Turkyilmaz, R.; Eroglu, H. The Investigation of Weight Loss Profiles on Weight Classes Sports Athletes. Int. J. Appl. Exerc. Physiol. 2019, 8, 62–68. [Google Scholar]

- Berkovich, B.-E.; Stark, A.H.; Eliakim, A.; Nemet, D.; Sinai, T. Rapid Weight Loss in Competitive Judo and Taekwondo Athletes: Attitudes and Practices of Coaches and Trainers. Int. J. Sport Nutr. Exerc. Metab. 2019, 29, 532–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barley, O.R.; Chapman, D.W.; Abbiss, C.R. Weight Loss Strategies in Combat Sports and Concerning Habits in Mixed Martial Arts. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 2018, 13, 933–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamseer, L.; Moher, D.; Clarke, M.; Ghersi, D.; Liberati, A.; Petticrew, M.; Shekelle, P.; Stewart, L.A.; The PRISMA-P Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015: Elaboration and explanation. BMJ 2015, 350, g7647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gusenbauer, M.; Haddaway, N.R. Which academic search systems are suitable for systematic reviews or meta-analyses? Evaluating retrieval qualities of Google Scholar, PubMed, and 26 other resources. Res. Synth. Methods 2020, 11, 181–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribas, M.R.; Scheffel, M.; Fernandes, P.; Bassan, J.C.; Izquierdo, E.D. Strategies to reduce pre-competition body weight in mixed martial arts. Arch. Med. Deporte Rev. Fed. Española Med. Deporte Confed. Iberoam. Med. Deporte 2017, 34, 321–325. [Google Scholar]

- Andreato, L.V.; Andreato, T.V.; Santos, J.F.d.S.; Esteves, J.V.D.C.; Moraes, S.M.F.; Franchini, E. Weight loss in mixed martial arts athletes. J. Combat. Sports Martial Arts 2014, 5, 117–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ribas, M.R.; de Oliveira, W.C.; de Souza, H.H.; dos Santos Ferreira, S.C.; Walesko, F.; Bassan, J.C. The Assessment of Hand Grip Strength and Rapid Weight Loss in Muay Thai Athletes. J. Exerc. Physiol. Online 2019, 22, 130–141. [Google Scholar]

- Xiong, N.Q.; Xian, C.Y.; Karppaya, H.; Jin, C.W.; Ramadas, A. Rapid Weight Loss Practices among Elite Combat Sports Athletes in Malaysia. Malays. J. Nutr. 2017, 23, 199–209. [Google Scholar]

- Kiningham, R.B.; Gorenflo, D.W. Weight loss methods of high school wrestlers. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2001, 33, 810–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Aranda, L.M.; Sanz-Matesanz, M.; Orozco-Durán, G.; González-Fernández, F.T.; Rodríguez-García, L.; Guadalupe-Grau, A. Effects of Different Rapid Weight Loss Strategies and Percentages on Performance-Related Parameters in Combat Sports: An Updated Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 5158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lakicevic, N.; Roklicer, R.; Bianco, A.; Mani, D.; Paoli, A.; Trivic, T.; Ostojic, S.M.; Milovancev, A.; Maksimovic, N.; Drid, P. Effects of Rapid Weight Loss on Judo Athletes: A Systematic Review. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mauricio, C.D.A.; Merino, P.; Merlo, R.; Vargas, J.J.N.; Chávez, J.R.; Pérez, D.V.; Aedo-Muñoz, E.A.; Slimani, M.; Brito, C.J.; Bragazzi, N.L.; et al. Rapid Weight Loss of Up to Five Percent of the Body Mass in Less Than 7 Days Does Not Affect Physical Performance in Official Olympic Combat Athletes with Weight Classes: A Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis. Front. Physiol. 2022, 13, 830229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fortes, L.S.; Costa, B.D.V.; Paes, P.P.; Cyrino, E.S.; Vianna, J.M.; Franchini, E. Effect of rapid weight loss on physical performance in judo athletes: Is rapid weight loss a help for judokas with weight problems? Int. J. Perform. Anal. Sport 2017, 17, 763–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniele, G.; Weinstein, R.N.; Wallace, P.W.; Palmieri, V.; Bianco, M. Rapid weight gain in professional boxing and correlation with fight decisions: Analysis from 71 title fights. Physician Sportsmed. 2016, 44, 349–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horswill, C.A.; Scott, J.R.; Dick, R.W.; Hayes, J. Influence of rapid weight gain after the weigh-in on success in collegiate wrestlers. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 1994, 26, 1290–1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Utter, A.; Kang, J. Acute Weight Gain and Performance in College Wrestlers. J. Strength Cond. Res. 1998, 12, 157–160. [Google Scholar]

- Pettersson, S.; Ekstrom, M.P.; Berg, C.M. Practices of Weight Regulation Among Elite Athletes in Combat Sports: A Matter of Mental Advantage? J. Athl. Train. 2013, 48, 99–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sansone, R.A.; Sawyer, R. Weight loss pressure on a 5 year old wrestler. Br. J. Sports Med. 2005, 39, e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alderman, B.; Landers, D.M.; Carlson, J.; Scott, J.R. Factors related to rapid weight loss practices among international-style wrestlers. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2004, 36, 249–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karninčić, H.; Baić, M.; Slačanac, K. Mood aspects of rapid weight loss in adolescent wrestlers. Kinesiol. Int. J. Fundam. Appl. Kinesiol. 2016, 48, 229–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrie, H.J.; Stover, E.A.; Horswill, C.A. Nutritional concerns for the child and adolescent competitor. Nutrition 2004, 20, 620–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boisseau, N. Consequences of Sport-Imposed Weight Restriction in Childhood. Ann. Nestlé (Engl. Ed.) 2006, 64, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filaire, E.; Maso, F.; Degoutte, F.; Jouanel, P.; Lac, G. Food restriction, performance, psychological state and lipid values in judo athletes. Int. J. Sports Med. 2001, 22, 454–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fortes, L.S.; Lira, H.A.; Andrade, J.; Oliveira, S.F.M.; Paes, P.P.; Vianna, J.M.; Vieira, L.F. Mood response after two weeks of rapid weight reduction in judokas. Arch. Budo 2018, 14, 87–94. [Google Scholar]

- Morales, J.; Ubasart, C.; Solana-Tramunt, M.; Villarrasa-Sapiña, I.; González, L.-M.; Fukuda, D.; Franchini, E. Effects of Rapid Weight Loss on Balance and Reaction Time in Elite Judo Athletes. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 2018, 13, 1371–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artioli, G.G.; Iglesias, R.T.; Franchini, E.; Gualano, B.; Kashiwagura, D.B.; Solis, M.Y.; Benatti, F.B.; Fuchs, M.; Junior, A.H.L. Rapid weight loss followed by recovery time does not affect judo-related performance. J. Sports Sci. 2010, 28, 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clarys, P.; Ramon, K.; Hagman, F.F.; Deriemaeker, P.; Zinzen, E. Influence of weight reduction on physical performance capacity in judokas. J. Combat. Sports Martial Arts 2010, 1, 71–76. [Google Scholar]

- Yarar, H. Rapid weight loss and athletic performance in combat sports. Int. J. Curric. Instr. 2022, 14, 2666–2678. [Google Scholar]

- Miranda, K.A.; Gheller, R.G.; Da Silva, I.M.; Picanco, L.A.; Dos Santos, J.O. Effects of gradual weight loss on strength levels and body composition in wrestlers athletes. J. Sports Med. Phys. Fit. 2021, 61, 401–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weldon, A.; Duncan, M.J.; Turner, A.; Christie, C.J.; Pang, C.M.C. Contemporary practices of strength and conditioning coaches in professional cricket. Int. J. Sports Sci. Sci. Coach. 2021, 16, 585–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weldon, A.; Duncan, M.J.; Turner, A.; Sampaio, J.; Noon, M.; Wong, D.; Lai, V.W. Contemporary practices of strength and conditioning coaches in professional soccer. Biol. Sport 2021, 38, 377–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhong, Y.; Weldon, A.; Bishop, C.; Li, Y. Practices of strength and conditioning coaches across Chinese high-performance sports. Int. J. Sports Sci. Sci. Coach. 2023, 18, 1442–1455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.C.; Park, K.J. Injuries and rapid weight loss in elite Korean wrestlers: An epidemiological study. Physician Sportsmed. 2021, 49, 308–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammer, E.; Sanfilippo, J.L.; Johnson, G.; Hetzel, S. Association of in-competition injury risk and the degree of rapid weight cutting prior to competition in division I collegiate wrestlers. Br. J. Sports Med. 2023, 57, 160–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.C.; Park, K.J. The effect of rapid weight loss on sports injury in elite taekwondo athletes. Physician Sportsmed. 2023, 51, 313–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zabaloy, S.; Tondelli, E.; Pereira, L.A.; Freitas, T.T.; Loturco, I. Training and testing practices of strength and conditioning coaches in Argentinian Rugby Union. Int. J. Sports Sci. Sci. Coach. 2022, 17, 1331–1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anyadike-Danes, K.; Donath, L.; Kiely, J. Coaches’ Perceptions of Common Planning Concepts Within Training Theory: An International Survey. Sports Med. Open 2023, 9, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kouassi, J.-P.; Gouthon, P.; Kouame, N.G.; Agbodjogbe, B.; Nouatin, B.; Tako, N.A. Perceptions and motivation of top-level judokas from cote d’ivoire about practice of rapid weight loss. S. Afr. J. Res. Sport Phys. Educ. Recreat. 2020, 42, 35–45. [Google Scholar]

- DeFreese, J.D.; Smith, A.L. Teammate social support, burnout, and self-determined motivation in collegiate athletes. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2013, 14, 258–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graupensperger, S.; Benson, A.J.; Kilmer, J.R.; Evans, M.B. Social (Un)distancing: Teammate Interactions, Athletic Identity, and Mental Health of Student-Athletes During the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Adolesc. Health 2020, 67, 662–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, C.L.; Haycraft, E.; Plateau, C.R. Teammate influences on the eating attitudes and behaviours of athletes: A systematic review. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2019, 43, 183–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Reference | Guilherme Giannini Artioli et al. [20] | Nikos Malliaropoulos et al. [43] | Rafael Kons et al. [42] | Ben-El Berkovich et al. [34] | Rafael L Kons et al. [3] | Nikola Todorović et al. [44] | Flavia Figlioli et al. [39] | Patrik Drid et al. [15] | Mathew Hillier et al. [40] | Rubens B. Santos-Junior et al. [13] | Marcelo Romanovitch Ribas et al. [51] | Leonardo Vidal Andreato et al. [52] | John Connor et al. [38] | Tyler White et al. [45] | Marijana Ranisavljev et al. [4] | Boris Dugonjić et al. [16] | Jonatas Ferreira Da Silva Santos et al. [19] | B.B. Vasconcelos et al. [7] | Marcelo Romanovitch Ribas et al. [53] | Stefano Amatori et al. [18] | Cecilia Castor-Praga et al. [36] | Léna Pélissier et al. [6] | Whye Lian Cheah et al. [37] | Hakan Yarar et al. [46] | Ng Qi Xiong et al. [54] | Reid Reale et al. [12] | Mean |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2010 | 2017 | 2017 | 2016 | 2020 | 2021 | 2021 | 2021 | 2019 | 2019 | 2017 | 2014 | 2019 | 2021 | 2022 | 2019 | 2016 | 2023 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2019 | 2020 | 2017 | 2017 | ||

| Country | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Brazil | England | Brazil | Israel | Brazil | 12 countries | 35 countries | 20 countries | — | Brazil | Brazil | Brazil | Ireland | England | 16 countries | 8 countries | Brazil | Brazil | Brazil | Italy | Mexico | France | Malaysia | — | Malaysia | Australia | — | |

| Sport | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Judo | Judo | Judo | Judo | Visually impaired judo | Sambo | Sambo | Sambo | MMA | MMA | MMA | MMA | MMA | Jiu-jitsu | Wrestling | Kickboxing | Taekwondo | Sanda | Muay Thai | Boxing | Wrestling, Taekwondo | Multiple combat sports | Multiple combat sports | Multiple combat sports | Multiple combat sports | Multiple combat sports | — | |

| Sample size (n) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 822 | 255 | 12 | 108 | 30 | 47 | 103 | 199 | 314 | 179 | 25 | 8 | 30 | 115 | 120 | 61 | 116 | 71 | 20 | 164 | 160 | 168 | 65 | 502 | 40 | 260 | — | |

| Male (%) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 74 | 74 | 100 | 100 | 67 | 0 | 100 | 66 | 91 | 92 | 100 | — | 100 | 94 | 68 | 100 | 62 | 72 | 100 | 88 | 60 | 48 | 68 | 74 | 65 | 65 | — | |

| Female (%) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 26 | 26 | 0 | 0 | 33 | 100 | 0 | 34 | 9 | 8 | 0 | — | 0 | 6 | 32 | 0 | 38 | 28 | 0 | 12 | 40 | 52 | 32 | 26 | 35 | 35 | — | |

| Competitive level | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| R, S, N, I | C, R, N, I | — | R, N, I | N, I | I | I | I | — | S, N, I | S, N | R, N | — | R, N, I | I | I | R, S, N, I | N | S, N, I | — | — | L, R N, I | Non-I | — | I | N, I | — | |

| Regional (%) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 17 | — | — | — | — | 0 | 0 | 0 | — | 0 | — | — | — | — | 0 | 0 | — | — | 0 | — | — | 12 | — | — | 0 | 0 | — | |

| State (%) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 38 | — | — | — | — | 0 | 0 | 0 | — | 29 | — | — | — | — | 0 | 0 | — | — | 50 | — | — | 0 | — | — | 0 | 16 | — | |

| National (%) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 24 | — | — | — | — | 0 | 0 | 0 | — | 43 | — | — | — | — | 0 | 0 | — | 100 | 40 | — | — | 38 | — | — | 0 | 27 | — | |

| International (%) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 21 | — | — | — | — | 100 | 100 | 100 | — | 28 | — | — | — | — | 100 | 100 | — | — | 10 | 18 | — | 47 | — | — | 100 | 47 | — | |

| Age (year) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 19.3 | 28.1 | 23.3 | 14.6 | 26.2 | 23.1 | 24.2 | 22.7 | 27.3 | 25.0 | 24.4 | 22.0 | 25.5 | 29.3 | 27.6 | 24.2 | 21.5 | 22.5 | 27.7 | 22.9 | 13.3 | 24.0 | 22.9 | 20.9 | 21.0 | 23.2 | 23.3 | |

| Body weight (kg) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 70.0 | 76.6 | 87.2 | 58.0 | 70.7 | 62.7 | 75.5 | 71.6 | 80.2 | 77.0 | 79.5 | 74.3 | 78.3 | — | 76.2 | 73.9 | 64.6 | 65.1 | 80.1 | 68.9 | 48.9 | 67.6 | — | — | 62.2 | 69.5 | 71.2 | |

| Height (m) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1.71 | 1.73 | 1.72 | 1.65 | 1.66 | 1.63 | 1.74 | 1.71 | — | 1.76 | 1.76 | 1.77 | 1.79 | — | 1.72 | 1.79 | 1.72 | 1.70 | 1.74 | 1.75 | 1.57 | 1.69 | — | — | — | 1.73 | 1.72 | |

| Number of competitions in past 12 month (n) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | 2.0 | 3.0 | — | 2.5 | — | — | 4.8 | 6.8 | — | 4.5 | — | — | — | — | — | — | 7.1 | 4.4 | |

| Age at start of training (year) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 9.1 | — | 10.2 | 5.5 | 15.6 | — | 11.2 | 11.3 | — | 19 | 16 | 18.6 | — | 25.8 | — | 14.5 | 12.8 | 16 | 18.7 | 16.2 | 6.8 | 10.7 | 14.7 | — | 10.7 | — | 13.9 | |

| Age at start of competing (year) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 10.7 | — | — | 6.8 | 18.1 | — | 12.7 | — | — | 20 | 19.6 | 19.7 | — | 26.7 | 14.7 | 15.3 | 13.4 | 17.4 | 22.4 | 18.2 | 8.0 | 12.8 | 16.6 | — | 12.8 | — | 17.9 | |

| Off-season weight (kg) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 71.1 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | 79 | 82.2 | — | 78.3 | 80.5 | — | 75.6 | 65.3 | 68.8 | 83.4 | — | — | — | — | — | 63.1 | — | 74.7 | |

| Prevalence of weight loss (%) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 86 | 84 | 100 | 80 | 67 | 89 | 90 | 87 | 97 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 97 | 59 | 83 | 100 | 81 | 90 | 100 | 88 | 96 | 95 | 66 | 100 | 93 | 88 | 89 | |

| Study | Guilherme Giannini Artioli et al. [20] | Nikos Malliaropoulos et al. [43] | Rafael Kons et al. [42] | Ben-El Berkovich et al. [34] | Rafael L Kons et al. [3] | Nikola Todorović et al. [44] | Flavia Figlioli et al. [39] | Patrik Drid et al. [15] | Mathew Hillier et al. [40] | Rubens B. Santos-Junior et al. [13] | Marcelo Romanovitch Ribas et al. [51] | Leonardo Vidal Andreato et al. [52] | John Connor et al. [38] | Tyler White et al. [45] | Marijana Ranisavljev et al. [4] | Boris Dugonjić et al. [16] | Jonatas Ferreira Da Silva Santos et al. [19] | B.B. Vasconcelos et al. [7] | Marcelo Romanovitch Ribas et al. [53] | Stefano Amatori et al. [18] | Cecilia Castor-Praga et al. [36] | Léna Pélissier et al. [6] | Whye Lian Cheah et al. [37] | Hakan Yarar et al. [46] | Ng Qi Xiong et al. [54] | Reid Reale et al. [12] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q1 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Q2 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Q3 | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | Y | N | N | N |

| Q4 | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | D | Y | Y |

| Q5 | Y | Y | D | D | D | D | D | D | D | D | Y | D | D | Y | Y | Y | D | Y | D | D | D | D | Y | D | D | D |

| Q6 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | D | Y | D | Y | Y | Y | Y | D | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | D | Y | Y |

| Q7 | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | Y | N | N | N |

| Q8 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Q9 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Q10 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y |

| Q11 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Q12 | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y |

| Q13 | D | D | D | D | D | D | D | D | D | D | D | D | D | D | D | D | D | D | D | D | D | D | D | D | D | D |

| Q14 | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N |

| Q15 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Q16 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Q17 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Q18 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | N | Y | N | Y | Y | N | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y |

| Q19 | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y |

| Q20 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y |

| Reference | Guilherme Giannini Artioli et al. [20] | Nikos Malliaropoulos et al. [43] | Rafael Kons et al. [42] | Ben-El Berkovich et al. [34] | Rafael L Kons et al. [3] | Nikola Todorović et al. [44] | Flavia Figlioli et al. [39] | Patrik Drid et al. [15] | Mathew Hillier et al. [40] | Rubens B. Santos-Junior et al. [13] | Marcelo Romanovitch Ribas et al. [51] | Leonardo Vidal Andreato et al. [52] | John Connor et al. [38] | Tyler White et al. [45] | Marijana Ranisavljev et al. [4] | Boris Dugonjić et al. [16] | Jonatas Ferreira Da Silva Santos et al. [19] | B.B. Vasconcelos et al. [7] | Marcelo Romanovitch Ribas et al. [53] | Stefano Amatori et al. [18] | Cecilia Castor-Praga et al. [36] | Léna Pélissier et al. [6] | Whye Lian Cheah et al. [37] | Hakan Yarar et al. [46] | Ng Qi Xiong et al. [54] | Reid Reale et al. [12] | Mean |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sport | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Judo | Judo | Judo | Judo | Visually impaired judo | Sambo | Sambo | Sambo | MMA | MMA | MMA | MMA | MMA | Jiu-jitsu | Wrestling | Kickboxing | Taekwondo | Sanda | Muay Thai | Boxing | Wrestling, Taekwondo | Multiple combat sports | Multiple combat sports | Multiple combat sports | Multiple combat sports | Multiple combat sports | — | |

| The number of people answered following questions | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 688 | 214 | 12 | 86 | 20 | 47 | 103 | 173 | 314 | 179 | 25 | 8 | 29 | 68 | 120 | 61 | 94 | 64 | 20 | 164 | 153 | 160 | 43 | 502 | 37 | 229 | 139 | |

| Age at start of weight loss (y) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 12.6 | — | — | 12.5 | 20.6 | 14.9 | 16.0 | 15.8 | — | 21.0 | — | 19.0 | — | — | 19.2 | 18.5 | 17.7 | 18.8 | — | 18.4 | — | 17.1 | — | 14.7 | 15.9 | 18.3 | 17.1 | |

| Number of weight loss in past 12 months (n) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 3.0 | — | — | 2.8 | — | — | 3.2 | — | — | 2.0 | 3.3 | 2.0 | — | — | — | 3.2 | 3.0 | — | 3.9 | 1.3 | — | — | — | 2.6 | 2.2 | 4.7 | 2.9 | |

| Highest weight loss (kg) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 4.0 | — | — | 2.7 | 7.1 | — | 8.0 | — | — | 12.0 | 13.9 | 7.6 | — | — | — | 6.2 | 4.7 | 6.5 | 11.1 | 3.8 | — | 5.1 | 4.9 | 5.4 | 5.1 | 5.9 | 6.7 | |

| (and body weight %) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 6.0 | — | — | 4.7 | 10.0 | — | 10.6 | — | — | 15.6 | 17.5 | 10.2 | — | — | — | 8.4 | 7.3 | 10.3 | 13.9 | 5.5 | — | 7.5 | — | — | 8.0 | 8.5 | 9.6 | |

| Habitual weight loss (kg) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1.6 | — | 3.5 | 1.5 | 2.8 | 3.3 | 5.0 | 5.3 | 7.1 | 10.0 | 9.3 | 5.0 | 6.2 | — | 3.6 | 3.5 | 1.9 | 2.8 | 8.5 | 1.3 | — | 2.8 | 3.4 | — | 2.9 | 2.8 | 4.3 | |

| (and body weight %) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2.5 | — | 4.0 | 2.6 | 4.0 | 5.2 | 6.6 | 7.4 | 8.9 | 13.0 | 11.7 | 6.7 | 7.9 | — | 4.7 | 4.9 | 3.0 | 4.5 | 10.6 | 1.8 | — | 4.1 | — | — | 4.7 | 4.1 | 5.8 | |

| Typical body weight regain in a week after competition (kg) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1.6 | — | 2.6 | 1.4 | 2.6 | 4.0 | 4.4 | — | — | 9.0 | 9.5 | 3.5 | 6.2 | — | 3.3 | 2.8 | 1.6 | 2.3 | 5.4 | 1.7 | — | 2.4 | — | — | 2.4 | 2.9 | 3.7 | |

| (and body weight %) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2.3 | — | 3.0 | 2.4 | 3.7 | 6.3 | 5.8 | — | — | 11.7 | 11.9 | 4.4 | 7.9 | — | 4.3 | 3.8 | 2.5 | 3.5 | 6.7 | 2.5 | — | 3.5 | — | — | 3.9 | 4.2 | 5.0 | |

| Number of days over which weight is usually lost (days) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 7.0 | — | — | 8.0 | 16.0 | 11.9 | 11.7 | 11.9 | — | — | 24.5 | 12.0 | — | — | 10.6 | 9.6 | 11.4 | 19.3 | 29.1 | 10.1 | — | 13.1 | — | — | 11.9 | 12.8 | 13.6 | |

| 0–7 days (%) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 72.1 | — | 33.3 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | 50 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | 37.2 | 36.9 | — | — | 45.9 | |

| 8–14 days (%) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 14.8 | — | 33.3 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | 31 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | 25.6 | 32.6 | — | — | 27.5 | |

| 15 days and over (%) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 13.1 | — | 33.3 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | 19 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | 24.6 | 30.5 | — | — | 24.1 | |

| Reference | Guilherme Giannini Artioli et al. [20] | Nikos Malliaropoulos et al. [43] | Rafael Kons et al. [42] | Ben-El Berkovich et al. [34] | Rafael L Kons et al. [3] | Nikola Todorović et al. [44] | Flavia Figlioli et al. [39] | Patrik Drid et al. [15] | Mathew Hillier et al. [40] | Rubens B. Santos-Junior et al. [13] | Marcelo Romanovitch Ribas et al. [51] | Leonardo Vidal Andreato et al. [52] | John Connor et al. [38] | Tyler White et al. [45] | Marijana Ranisavljev et al. [4] | Boris Dugonjić et al. [16] | Jonatas Ferreira Da Silva Santos et al. [19] | B.B. Vasconcelos et al. [7] | Marcelo Romanovitch Ribas et al. [53] | Stefano Amatori et al. [18] | Cecilia Castor-Praga et al. [36] | Léna Pélissier et al. [6] | Whye Lian Cheah et al. [37] | Hakan Yarar et al. [46] | Ng Qi Xiong et al. [54] | Reid Reale et al. [12] | Mean |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sport | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Judo | Judo | Judo | Judo | Visually impaired judo | Sambo | Sambo | Sambo | MMA | MMA | MMA | MMA | MMA | Jiu-jitsu | Wrestling | Kickboxing | Taekwondo | Sanda | Muay Thai | Boxing | Wrestling, Taekwondo | Multiple combat sports | Multiple combat sports | Multiple combat sports | Multiple combat sports | Multiple combat sports | — | |

| Increased exercise (more than usual) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 243 | 192 | 279 | 216 | 160 | 203 | 179 | 188 | 213 | 244 | 230 | 238 | 181 | 195 | 201 | 225 | 218 | 260 | 295 | 209 | 217 | 209 | 255 | — | 213 | 194 | 218 | |

| Gradual dieting to lose weight in 2 wk or more | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 145 | 180 | 163 | 146 | 173 | 221 | 218 | 217 | 271 | 249 | 240 | 150 | 245 | 219 | 226 | 218 | 172 | — | 295 | 199 | — | 179 | 224 | — | 201 | 227 | 208 | |

| Restricting fluid ingestion | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 144 | 151 | 213 | 95 | 143 | 183 | 157 | 167 | 201 | 237 | 268 | 163 | 233 | 129 | 141 | 164 | 155 | 192 | 295 | 115 | 183 | 153 | 113 | — | 149 | 201 | 174 | |

| Skipping 1 or 2 meals | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 158 | 125 | 163 | 160 | 95 | 193 | 168 | 176 | 103 | 111 | — | 138 | 147 | 165 | 149 | 159 | 149 | 125 | 270 | 95 | 183 | 145 | 130 | — | 184 | 161 | 152 | |

| Training with rubber/plastic layers | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 116 | 83 | 97 | — | 92 | 150 | 192 | 175 | — | 234 | 228 | 131 | 146 | 50 | 117 | 148 | 168 | 117 | 285 | 159 | 216 | 158 | 115 | 150 | — | 113 | 150 | |

| Training intentionally in heated training rooms | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 154 | 90 | 187 | 86 | 113 | 157 | 171 | 168 | 117 | 184 | 214 | 138 | 114 | 94 | 151 | 126 | 154 | 173 | 295 | 120 | 178 | 119 | 150 | — | 149 | 114 | 149 | |

| Saunas | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 56 | 100 | 121 | 35 | 87 | 184 | 198 | 196 | 160 | 176 | 248 | 113 | 159 | 120 | 180 | 166 | 79 | 63 | 210 | 75 | 187 | 120 | 57 | 115 | 138 | 152 | 134 | |

| Fasting (not eating all day) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 106 | 102 | 121 | 69 | 85 | 144 | 113 | 117 | 119 | 147 | — | 144 | 157 | 126 | 109 | 93 | 137 | 129 | 295 | 52 | 191 | 94 | 136 | — | 86 | 131 | 125 | |

| Spitting | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 134 | — | 92 | 20 | 87 | 91 | 127 | 115 | — | 146 | — | 163 | 72 | 45 | 102 | 87 | 93 | 109 | 230 | 28 | 208 | 28 | 39 | 34 | 89 | 66 | 96 | |

| Use rubber/plastic layers without exercising | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 90 | 45 | 71 | — | 95 | 89 | 114 | 110 | — | — | — | 63 | 7 | 41 | 80 | 41 | 45 | — | — | 55 | 161 | 86 | 69 | — | — | 37 | 72 | |

| Laxatives | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 41 | — | 25 | 1 | 55 | 30 | 55 | 49 | 47 | 38 | — | 19 | 50 | 45 | 45 | 20 | 129 | 23 | — | 27 | 148 | 31 | 28 | 30 | 89 | 34 | 46 | |

| Diuretic | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 32 | — | 33 | 1 | 58 | 38 | 40 | 38 | 55 | 70 | — | 88 | 19 | 23 | 31 | 16 | 150 | 27 | — | 19 | 138 | 27 | 27 | 20 | 81 | 22 | 46 | |

| Diet pills | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 12 | — | — | 0 | — | 33 | 38 | 34 | 35 | 60 | — | 25 | 12 | 29 | 26 | 28 | 181 | 7 | — | 17 | 150 | 10 | 25 | 33 | 68 | 12 | 40 | |

| Vomiting | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 11 | — | 17 | 6 | 48 | 23 | 27 | 30 | 6 | 9 | — | — | 0 | 32 | 27 | 5 | — | 6 | — | 10 | 171 | 16 | 36 | — | 36 | 11 | 26 | |

| Reference | Guilherme Giannini Artioli et al. [20] | Nikos Malliaropoulos et al. [43] | Rafael Kons et al. [42] | Ben-El Berkovich et al. [34] | Rafael L Kons et al. [3] | Nikola Todorović et al. [44] | Flavia Figlioli et al. [39] | Patrik Drid et al. [15] | Mathew Hillier et al. [40] | Rubens B. Santos-Junior et al. [13] | Marcelo Romanovitch Ribas et al. [51] | Leonardo Vidal Andreato et al. [52] | John Connor et al. [38] | Tyler White et al. [45] | Marijana Ranisavljev et al. [4] | Boris Dugonjić et al. [16] | Jonatas Ferreira Da Silva Santos et al. [19] | B.B. Vasconcelos et al. [7] | Marcelo Romanovitch Ribas et al. [53] | Stefano Amatori et al. [18] | Cecilia Castor-Praga et al. [36] | Léna Pélissier et al. [6] | Whye Lian Cheah et al. [37] | Hakan Yarar et al. [46] | Ng Qi Xiong et al. [54] | Reid Reale et al. [12] | Mean |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sport | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Judo | Judo | Judo | Judo | Visually impaired judo | Sambo | Sambo | Sambo | MMA | MMA | MMA | MMA | MMA | Jiu-jitsu | Wrestling | Kickboxing | Taekwondo | Sanda | Muay Thai | Boxing | Wrestling, Taekwondo | Multiple combat sports | Multiple combat sports | Multiple combat sports | Multiple combat sports | Multiple combat sports | — | |

| Coach | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 296 | — | 375 | — | 410 | 347 | 332 | 345 | — | — | 440 | — | 372 | — | 317 | 402 | — | 350 | 495 | — | 365 | 268 | 360 | — | 433 | 353 | 368 | |

| Training partners/fellows | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| — | — | 241 | — | 340 | 257 | 255 | 254 | — | — | 446 | — | 396 | — | 260 | — | — | — | 415 | — | 219 | 327 | 384 | — | 378 | — | 321 | |

| Physical trainer | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 211 | — | 175 | — | 395 | 279 | 234 | 243 | — | — | — | — | 259 | — | 221 | 256 | — | 340 | 395 | — | 210 | 357 | 405 | — | 335 | 174 | 281 | |

| Other athletes (same sport) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 284 | — | 225 | — | 295 | 219 | 258 | 241 | — | — | 448 | — | — | — | 249 | 269 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | 290 | 278 | |

| Former athlete | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 259 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | 215 | — | 336 | 100 | — | — | 386 | 330 | — | — | 271 | 271 | |

| Nutritionist/Dietitian | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 190 | — | 175 | — | 300 | 187 | 194 | 184 | — | — | — | — | 236 | — | 217 | 121 | — | 255 | 206 | — | 255 | 436 | 240 | — | 373 | 210 | 236 | |

| Parents | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 228 | — | 183 | — | 270 | 270 | 233 | 248 | — | — | 180 | — | 130 | — | 214 | 195 | — | 246 | 0 | — | 303 | 412 | 282 | — | 308 | 191 | 229 | |

| Doctor/Physician | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 151 | — | 142 | — | 250 | 174 | 192 | 183 | — | — | 228 | — | 163 | — | 180 | 128 | — | 186 | 100 | — | 151 | 447 | 219 | — | 213 | 149 | 192 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhong, Y.; Song, Y.; Artioli, G.G.; Gee, T.I.; French, D.N.; Zheng, H.; Lyu, M.; Li, Y. The Practice of Weight Loss in Combat Sports Athletes: A Systematic Review. Nutrients 2024, 16, 1050. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16071050

Zhong Y, Song Y, Artioli GG, Gee TI, French DN, Zheng H, Lyu M, Li Y. The Practice of Weight Loss in Combat Sports Athletes: A Systematic Review. Nutrients. 2024; 16(7):1050. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16071050

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhong, Yuming, Yuou Song, Guilherme Giannini Artioli, Thomas I. Gee, Duncan N. French, Hang Zheng, Mengde Lyu, and Yongming Li. 2024. "The Practice of Weight Loss in Combat Sports Athletes: A Systematic Review" Nutrients 16, no. 7: 1050. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16071050

APA StyleZhong, Y., Song, Y., Artioli, G. G., Gee, T. I., French, D. N., Zheng, H., Lyu, M., & Li, Y. (2024). The Practice of Weight Loss in Combat Sports Athletes: A Systematic Review. Nutrients, 16(7), 1050. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16071050