From Childhood Interpersonal Trauma to Binge Eating in Adults: Unraveling the Role of Personality and Maladaptive Regulation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Binge Eating

2.2.2. Maltreatment

2.2.3. Bullying

2.2.4. Harm Avoidance and Self-Directedness

2.2.5. Maladaptive Cognitive-Emotional Regulation

2.3. Procedure

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics and Correlations

3.2. Mediation Models

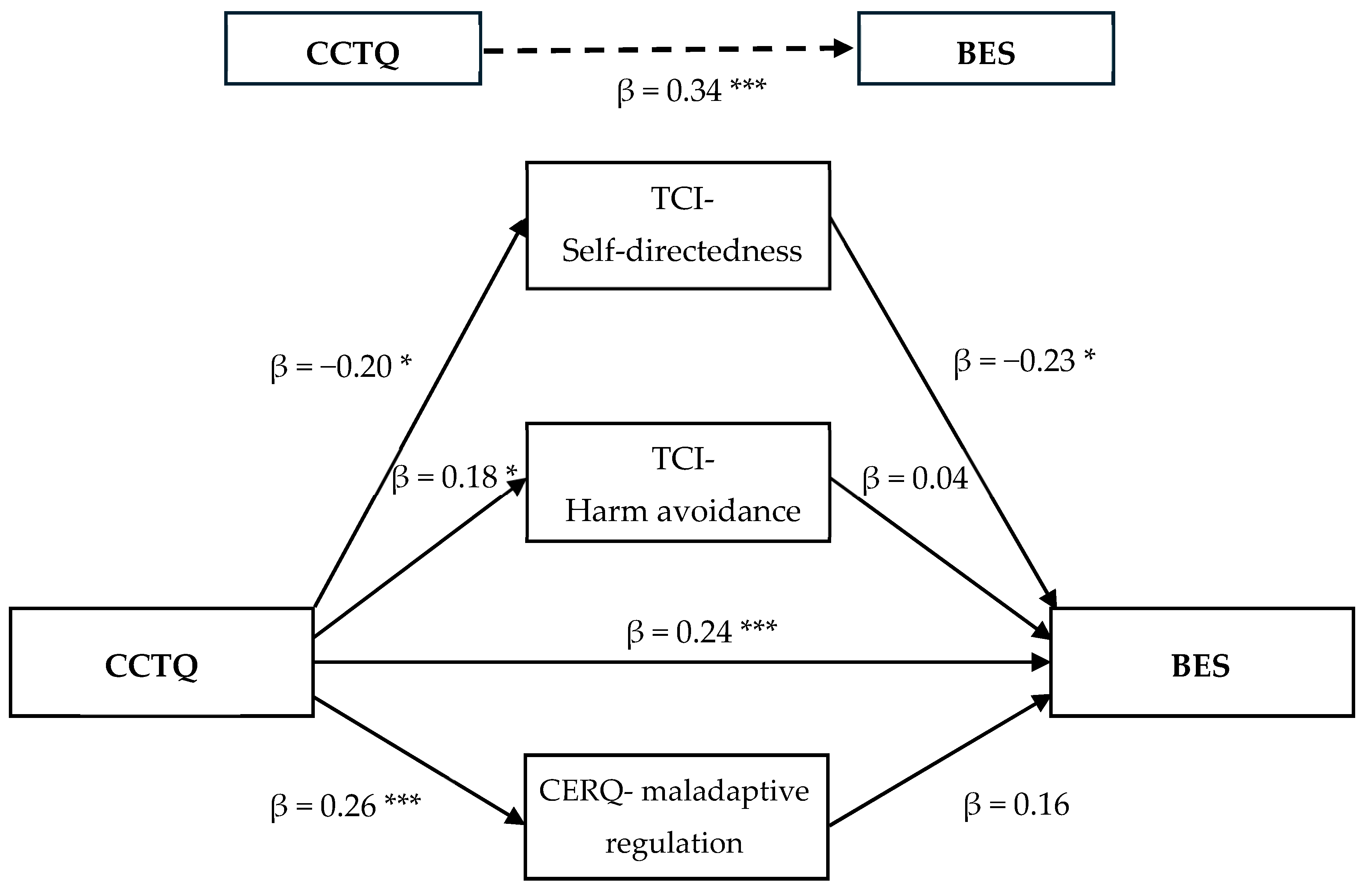

3.2.1. Mediation Model 1

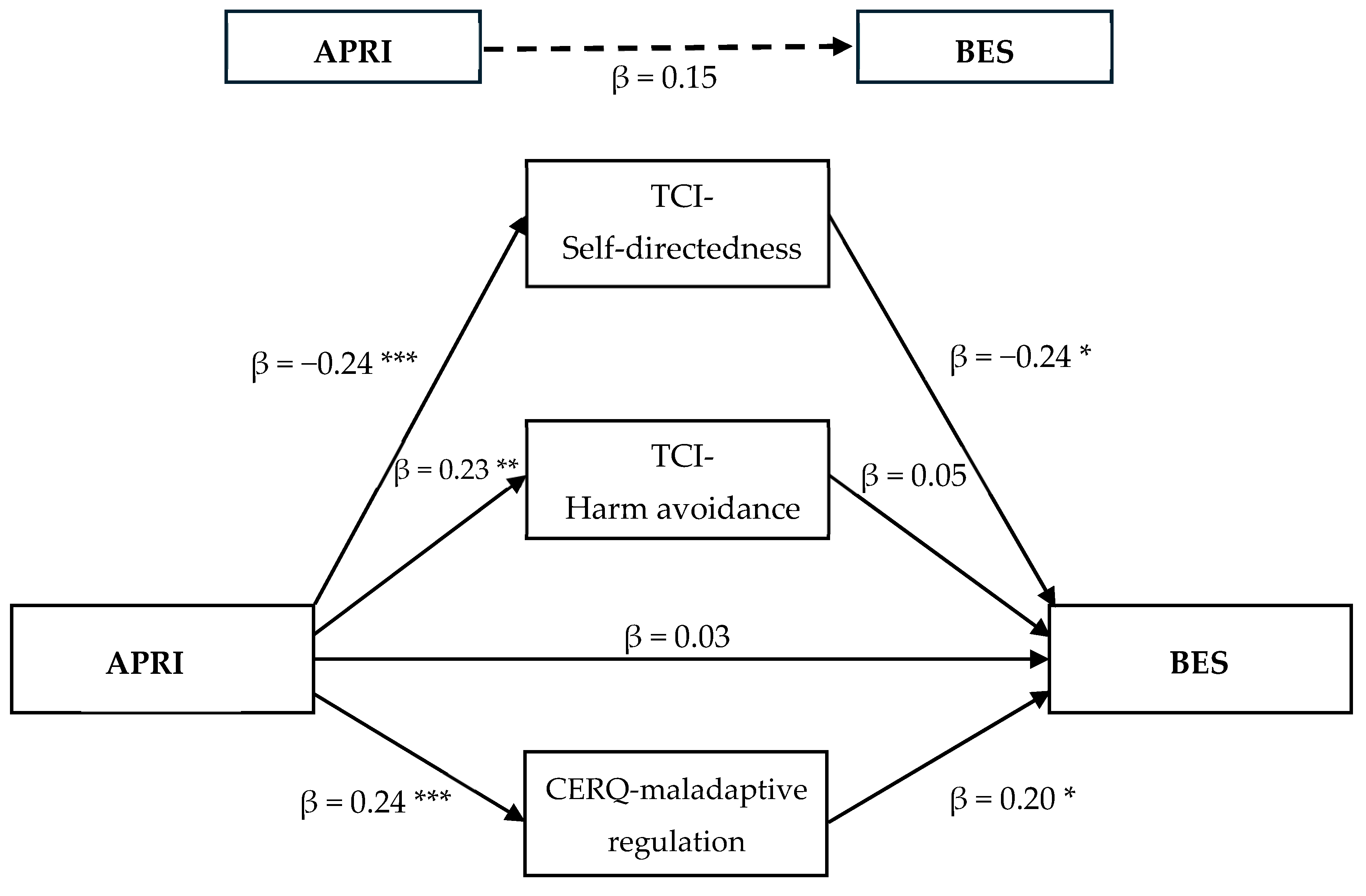

3.2.2. Mediation Model 2

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-5-TR, 5th ed.; American Psychiatric Association Publishing: Washington, DC, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Kessler, R.C.; Berglund, P.A.; Chiu, W.T.; Deitz, A.C.; Hudson, J.I.; Shahly, V.; Aguilar-Gaxiola, S.; Alonso, J.; Angermeyer, M.C.; Benjet, C.; et al. The prevalence and correlates of binge eating disorder in the world health organization world mental health surveys. Biol. Psychiatry 2013, 73, 904–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, G.T.; Sysko, R. Frequency of binge eating episodes in bulimia nervosa and binge eating disorder: Diagnostic considerations. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2009, 42, 603–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udo, T.; Grilo, C.M. Prevalence and correlates of DSM-5–defined eating disorders in a nationally representative sample of US adults. Biol. Psychiatry 2018, 84, 345–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dziewa, M.; Bańka, B.; Herbet, M.; Piątkowska-Chmiel, I. Eating disorders and diabetes: Facing the dual challenge. Nutrients 2023, 15, 3955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanofsky-Kraff, M.; Schvey, N.A.; Grilo, C.M. A developmental framework of binge-eating disorder based on pediatric loss of control eating. Am. Psychol. 2020, 75, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kong, S.; Bernstein, K. Mental health: Childhood trauma as a predictor of eating psychopathology and its mediating variables in patients with eating disorders. J. Clin. Nurs. 2009, 18, 1897–1907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pignatelli, A.M.; Wampers, M.; Loriedo, C.; Biondi, M.; Vanderlinden, J. Childhood neglect in eating disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Trauma Dissociation 2017, 18, 100–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molendijk, M.L.; Hoek, H.W.; Brewerton, T.D.; Elzinga, B.M. Childhood maltreatment and eating disorder pathology: A systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis. Psychol. Med. 2017, 47, 1402–1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clément, M.È.; Julien, D.; Lévesque, S.; Flores, J. La Violence Familiale Dans la vie des Enfants du Québec. Les Attitudes Parentales et les Pratiques Familiales. Résultats de la 4e Édition de L’enquête. Institut de la Statistique du Québec. 2019. Available online: https://statistique.quebec.ca/fr/fichier/la-violence-familiale-dans-la-vie-des-enfants-du-quebec-2018-les-attitudes-parentales-et-les-pratiques-familiales.pdf (accessed on 29 October 2024).

- Dugal, C.; Bigras, N.; Godbout, N.; Bélanger, C. Childhood interpersonal trauma and its repercussions in adulthood: An analysis of psychological and interpersonal sequelae. In A Multidimensional Approach to Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder—From Theory to Practice; El-Baalbaki, G., Fortin, C., Eds.; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Janiri, D.; Sani, G.; Piras, F.; Spalletta, G. Introduction on childhood trauma in mental disorders: A comprehensive approach. In Childhood Trauma in Mental Disorders: A Comprehensive Approach; Spalletta, G., Janiri, D., Piras, F., Sani, G., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Idsoe, T.; Vaillancourt, T.; Dyregrov, A.; Hagen, K.A.; Ogden, T.; Nærde, A. Bullying victimization and trauma. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 11, 480353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olofsson, M.E.; Oddli, H.W.; Hoffart, A.; Eielsen, H.P.; Vrabel, K.A.R. Change processes related to long-term outcomes in eating disorders with childhood trauma: An explorative qualitative study. J. Couns. Psychol. 2020, 67, 51–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sweetingham, R.; Waller, G. Childhood experiences of being bullied and teased in the eating disorders. Eur. Eat. Disord. Rev. 2008, 16, 401–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watterson, R.L.; Crowe, M.; Jordan, J.; Lovell, S.; Carter, J.D. A tale of childhood loss, conditional acceptance and a fear of abandonment: A qualitative study taking a narrative approach to eating disorders. Qual. Health Res. 2023, 33, 270–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, J.D. Treatment implications of altered affect regulation and information processing following child maltreatment. Psychiatr. Ann. 2005, 35, 410–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cicchetti, D.; Toth, S. Child maltreatment and developmental psychopathology: A multilevel perspective. In Psychopathology: Maladaptation and Psychopathology, 3rd ed.; Cicchetti, D., Ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2016; Volume 3, pp. 457–512. [Google Scholar]

- Erozkan, A. The link between types of attachment and childhood trauma. Univers. J. Educ. Res. 2016, 4, 1071–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cicchetti, D.; Rogosch, F.A. Adaptive coping under conditions of extreme stress: Multilevel influences on the determinants of resilience in maltreated children. New Dir. Child Adolesc. Dev. 2009, 124, 47–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gratz, K.; Paulson, A.; Jakupcak, M.; Tull, M.T. Exploring the relationship between childhood maltreatment and intimate partner abuse: Gender differences in the mediating role of emotion dysregulation. Violence Vict. 2009, 24, 68–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burns, E.E.; Jackson, J.L.; Harding, H.G. Child maltreatment, emotion regulation, and posttraumatic stress: The impact of emotional abuse. J. Aggress. Maltreatment Trauma 2010, 19, 801–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dingemans, A.; Danner, U.; Parks, M. Emotion regulation in binge eating disorder: A review. Nutrients 2017, 9, 1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moulton, S.J.; Newman, E.; Power, K.; Swanson, V.; Day, K. Childhood trauma and eating psychopathology: A mediating role for dissociation and emotion dysregulation? Child Abus. Negl. 2015, 39, 167–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burns, E.E.; Fischer, S.; Jackson, J.L.; Harding, H.G. Deficits in emotion regulation mediate the relationship between childhood abuse and later eating disorder symptoms. Child Abus. Negl. 2012, 36, 32–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garnefski, N.; Kraaij, V.; Spinhoven, P. Negative life events, cognitive emotion regulation and emotional problems. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2001, 30, 1311–1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walenda, A.; Kostecka, B.; Santangelo, P.S.; Kucharska, K. Examining emotion regulation in binge-eating disorder. Borderline Personal. Disord. Emot. Dysregulation 2021, 8, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huh, H.J.; Kim, K.H.; Lee, H.-K.; Chae, J.-H. The relationship between childhood trauma and the severity of adulthood depression and anxiety symptoms in a clinical sample: The mediating role of cognitive emotion regulation strategies. J. Affect. Disord. 2017, 213, 44–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, J.Y.; Oh, K.J. Cumulative childhood trauma and psychological maladjustment of sexually abused children in Korea: Mediating effects of emotion regulation. Child Abus. Negl. 2014, 38, 296–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dalle Grave, R.; Calugi, S.; El Ghoch, M.; Marzocchi, R.; Marchesini, G. Personality traits in obesity associated with binge eating and/or night eating. Curr. Obes. Rep. 2014, 3, 120–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeCarvalho, H.W.; Pereira, R.; Frozi, J.; Bisol, L.W.; Ottoni, G.L.; Lara, D.R. Childhood trauma is associated with maladaptive personality traits. Child Abus. Negl. 2015, 44, 18–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.B.; Wang, Z.M.; Hou, Y.Z.; Wang, Y.; Liu, J.T.; Wang, C.Y. Effects of childhood trauma on personality in a sample of chinese adolescents. Child Abus. Negl. 2014, 38, 788–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peterson, C.B.; Thuras, P.; Ackard, D.M.; Mitchell, J.E.; Berg, K.; Sandager, N.; Wonderlich, S.A.; Pederson, M.W.; Crow, S.J. Personality dimensions in bulimia nervosa, binge eating disorder, and obesity. Compr. Psychiatry 2010, 51, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cloninger, C.R.; Svrakic, D.M.; Przybeck, T.R. A psychobiological model of temperament and character. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 1993, 50, 975–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amianto, F.; Siccardi, S.; Abbate-Daga, G.; Marech, L.; Barosio, M.; Fassino, S. Does anger mediate between personality and eating symptoms in bulimia nervosa? Psychiatry Res. 2012, 200, 502–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunkley, D.M.; Masheb, R.M.; Grilo, C.M. Childhood maltreatment, depressive symptoms, and body dissatisfaction in patients with binge eating disorder: The mediating role of self-criticism. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2010, 43, 274–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillaume, S.; Jaussent, I.; Maimoun, L.; Ryst, A.; Seneque, M.; Villain, L.; Hamroun, D.; Lefebvre, P.; Renard, E.; Courtet, P. Associations between adverse childhood experiences and clinical characteristics of eating disorders. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 35761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meneguzzo, P.; Cazzola, C.; Castegnaro, R.; Buscaglia, F.; Bucci, E.; Pillan, A.; Garolla, A.; Bonello, E.; Todisco, P. Associations between trauma, early maladaptive schemas, personality traits, and clinical severity in eating disorder patients: A clinical presentation and mediation analysis. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 661924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barańczuk, U. The five factor model of personality and emotion regulation: A meta-analysis. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2019, 139, 217–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, D.J.; Kratsiotis, I.K.; Niven, K.; Holman, D. Personality traits and emotion regulation: A targeted review and recommendations. Emotion 2020, 20, 63–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gormally, J.; Black, S.; Daston, S.; Rardin, D. The assessment of binge eating severity among obese persons. Addict. Behav. 1982, 7, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunault, P.; Gaillard, P.; Ballon, N.; Couet, C.; Isnard, P.; Cook, S.; Delbachian, I.; Réveillère, C.; Courtois, R. Validation de la version française de la Binge Eating Scale: Étude de sa structure factorielle, de sa consistance interne et de sa validité de construit en population clinique et non clinique. L’Encephale 2016, 42, 426–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Godbout, N.; Bigras, N.; Sabourin, S. Childhood Cumulative Trauma Questionnaire (CCTQ). 2017; unpublished document. [Google Scholar]

- Bremner, J.D.; Bolus, R.; Mayer, E.A. Psychometric properties of the Early Trauma Inventory-Self Report. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 2007, 195, 211–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Briere, J.; Runtz, M. Differential adult symptomatology associated with three types of child abuse histories. Child Abus. Negl. 1990, 14, 357–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Godbout, N.; Dutton, D.G.; Lussier, Y.; Sabourin, S. Early exposure to violence, domestic violence, attachment representations, and marital adjustment. Pers. Relatsh. 2009, 16, 365–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godbout, N.; Lussier, Y.; Sabourin, S. Early abuse experiences and subsequent gender differences in couple adjustment. Violence Vict. 2006, 21, 744–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parada, R. Adolescent Peer Relations Instrument: A theoretical and Empirical Basis for the Measurement of Participant Roles. In Bullying and Victimisation of Adolescence: An Interim Test Manual and a Research Monograph: A Test Manual; Publication Unit, Self-concept Enhancement and Learning Facilitation (SELF) Research Centre, University of Western Sydney: Penright South, Australia, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Cloninger, C.R.; Przybeck, T.R.; Svrakic, D.M.; Wetzel, R.D. The Temperament and Character Inventory (TCI): A Guide to Its Development and Use; Center for Psychobiology of Personality: St. Louis, MI, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach; Guilford: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Gruhn, M.A.; Compas, B.E. Effects of maltreatment on coping and emotion regulation in childhood and adolescence: A meta-analytic review. Child Abus. Negl. 2020, 103, 104446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vacca, M.; Cerolini, S.; Zegretti, A.; Zagaria, A.; Lombardo, C. Bullying victimization and adolescent depression, anxiety and stress: The mediation of cognitive emotion regulation. Children 2023, 10, 1897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Copeland, W.E.; Bulik, C.M.; Zucker, N.; Wolke, D.; Lereya, S.T.; Costello, E.J. Does childhood bullying predict eating disorder symptoms? A prospective, longitudinal analysis. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2015, 48, 1141–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lie, S.Ø.; Bulik, C.M.; Andreassen, O.A.; Rø, Ø.; Bang, L. The association between bullying and eating disorders: A case-control study. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2021, 54, 1405–1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lie, S.Ø.; Rø, Ø.; Bang, L. Is bullying and teasing associated with eating disorders? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2019, 52, 497–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broerman, R. Diathesis-stress model. In Encyclopedia of Personality and Individual Differences; Zeigler-Hill, V., Shackelford, T.K., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Stice, E. Interactive and mediational etiologic models of eating disorder onset: Evidence from prospective studies. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2016, 12, 359–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingram, R.E.; Luxton, D.D. Vulnerability-stress models. In Development of Psychopathology: A Vulnerability-Stress Perspective; Hankin, B.L., Abela, J.R., Eds.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2005; pp. 32–46. [Google Scholar]

- Feinson, M.C.; Hornik-Lurie, T. ‘Not good enough:’ Exploring self-criticism’s role as a mediator between childhood emotional abuse adult binge eating. Eat. Behav. 2016, 23, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waller, G.; Meyer, C.; Ohanian, V.; Elliott, P.; Dickson, C.; Sellings, J. The psychopathology of bulimic women who report childhood sexual abuse: The mediating role of core beliefs. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 2001, 189, 700–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grucza, R.A.; Przybeck, T.R.; Cloninger, C.R. Prevalence and correlates of binge eating disorder in a community sample. Compr. Psychiatry 2007, 48, 124–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Riel, L.; Van den Berg, E.; Polak, M.; Geerts, M.; Peen, J.; Ingenhoven, T.J.M.; Dekker, J.J.M. Personality functioning in obesity and binge eating disorder: Combining a psychodynamic and trait perspective. J. Psychiatr. Pract. 2020, 26, 472–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roazzi, A.; Attili, G.; Di Pentima, L.; Toni, A. Locus of control in maltreated children: The impact of attachment and cumulative trauma. Psychol. Res. Rev. 2016, 29, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brewerton, T.D. An overview of trauma-informed care and practice for eating disorders. J. Aggress. Maltreatment Trauma 2019, 28, 445–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trottier, K.; MacDonald, D.E. Update on psychological trauma, other severe adverse experiences and eating disorders: State of the research and future research directions. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2017, 19, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variables | M | SD | N |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. BES (/46) | 22.47 | 8.89 | 146 |

| 2. CCTQ (/89) | 12.54 | 12.66 | 146 |

| 3. APRI (/126) | 45.95 | 18.89 | 146 |

| 4. CERQ-maladaptive | 39.45 | 9.14 | 146 |

| regulation (/80) | |||

| 5. TCI-Self-directedness (/100) | 61.95 | 19.34 | 146 |

| 6. TCI-Harm avoidance (/100) | 62.95 | 25.56 | 146 |

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. BES | - | |||||

| 2. CCTQ | 0.34 ** | - | ||||

| 3. APRI | 0.15 | 0.39 ** | - | |||

| 4. CERQ-maladaptive | 0.37 ** | 0.26 ** | 0.24 ** | - | ||

| regulation | ||||||

| 5. TCI-Self-directedness | −0.39 ** | −0.20 * | −0.24 ** | −0.57 ** | - | |

| 6. TCI-Harm avoidance | 0.28 ** | 0.18 * | 0.23 ** | 0.45 ** | −0.55 ** | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bellehumeur-Béchamp, L.; Legendre, M.; Bégin, C. From Childhood Interpersonal Trauma to Binge Eating in Adults: Unraveling the Role of Personality and Maladaptive Regulation. Nutrients 2024, 16, 4427. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16244427

Bellehumeur-Béchamp L, Legendre M, Bégin C. From Childhood Interpersonal Trauma to Binge Eating in Adults: Unraveling the Role of Personality and Maladaptive Regulation. Nutrients. 2024; 16(24):4427. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16244427

Chicago/Turabian StyleBellehumeur-Béchamp, Lily, Maxime Legendre, and Catherine Bégin. 2024. "From Childhood Interpersonal Trauma to Binge Eating in Adults: Unraveling the Role of Personality and Maladaptive Regulation" Nutrients 16, no. 24: 4427. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16244427

APA StyleBellehumeur-Béchamp, L., Legendre, M., & Bégin, C. (2024). From Childhood Interpersonal Trauma to Binge Eating in Adults: Unraveling the Role of Personality and Maladaptive Regulation. Nutrients, 16(24), 4427. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16244427