The Greater the Number of Altered Eating Behaviors in Obesity, the More Severe the Psychopathology

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Procedures and Assessment

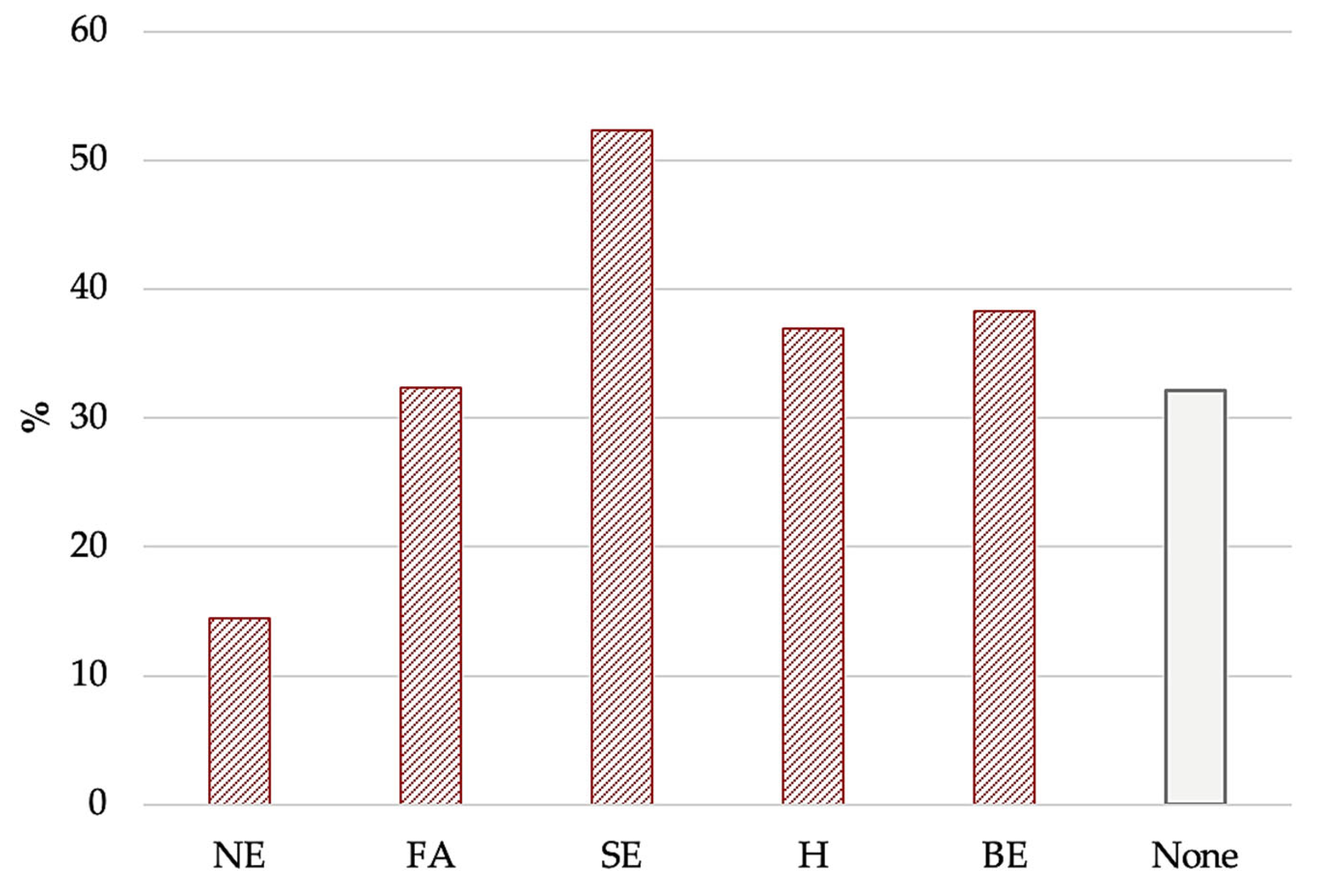

- EBA-O [33]: This is a self-administered questionnaire and consists of 18 items that evaluate 5 AEBs (i.e., “food addiction”, “night eating”, “binge eating”, “sweet eating”, and “hyperphagia”) over the previous three months. A cut off score ≥ 4 was applied for the factors and total score to indicate clinically relevant AEBs.

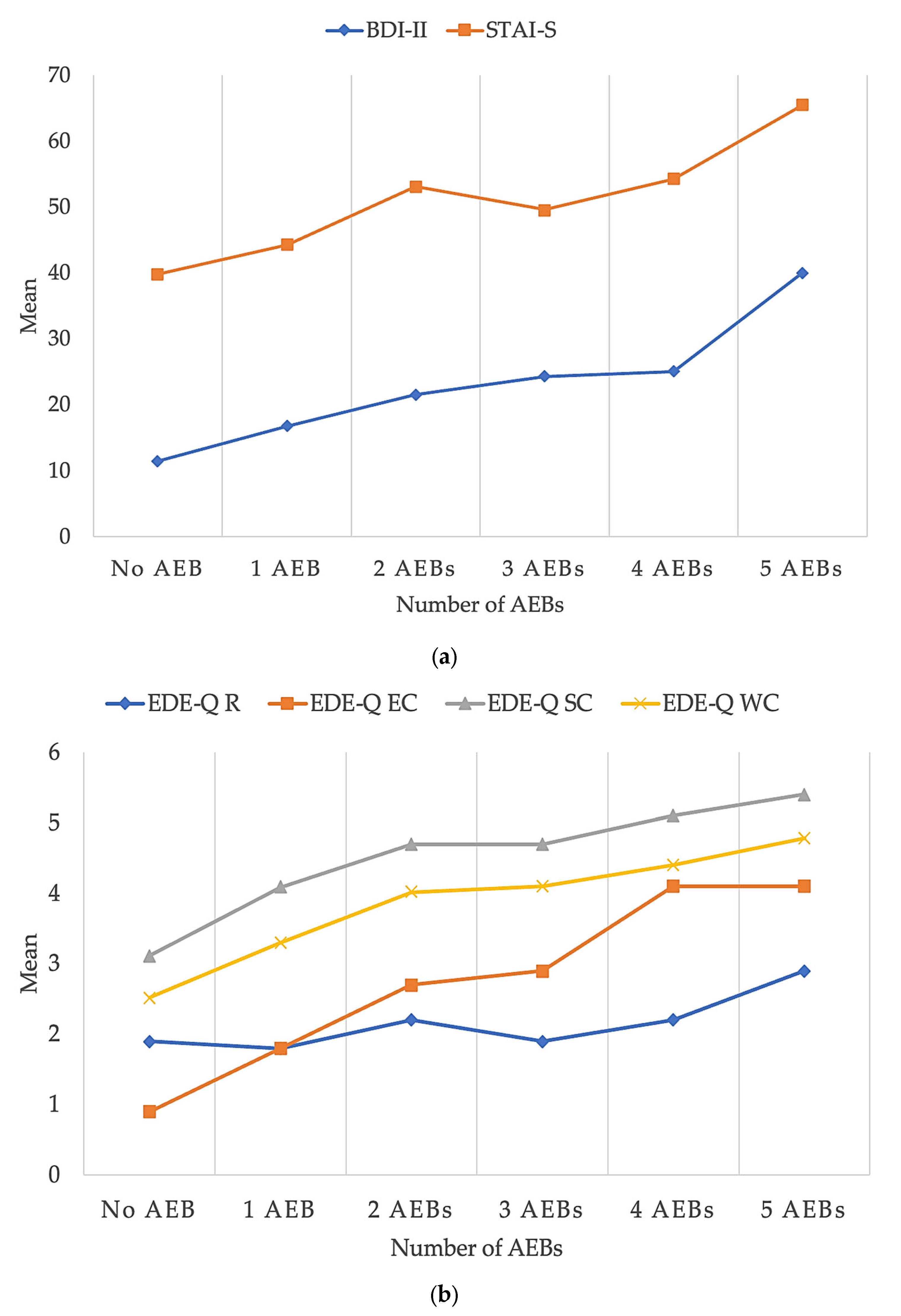

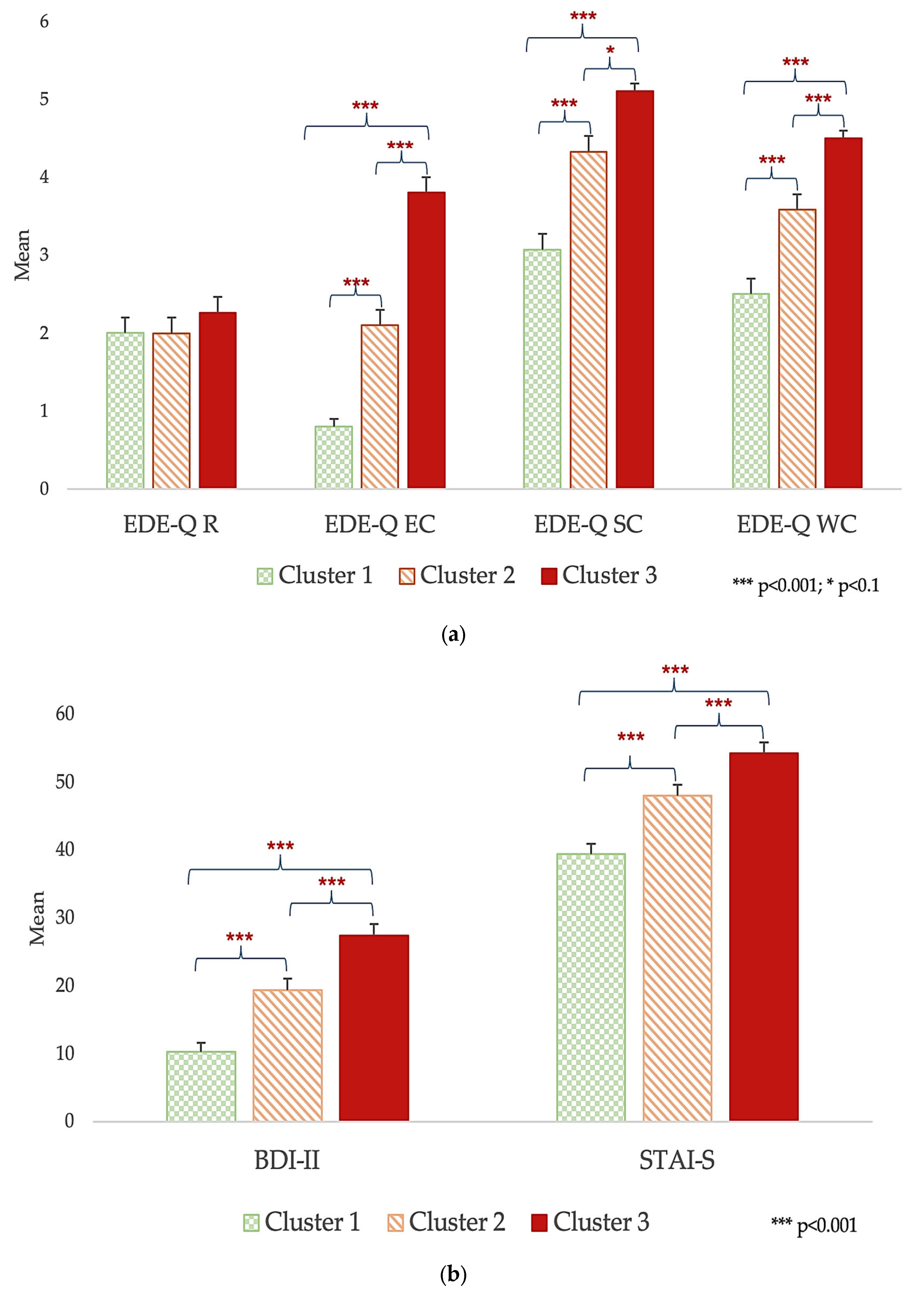

- Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire (EDE-Q 6.0) [35]: This is a self-administered questionnaire assessing eating psychopathology over the past 28 days with 36 items, rated 0–6. The tool provides a mean Global Score and four subscales, namely restraint (R), eating concern (EC), shape concern (SC), and weight concern (WC), with higher scores indicating more impaired eating behaviors.

- State–Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) [36]: this is a self-administered questionnaire made up of 40 items that assess state (STAI-S) and trait (STAI-T) anxiety.

- Beck Depression Inventory (BDI-II) [37]: this is a self-report questionnaire used to assess the presence and severity of depression through 21 items; scores of <10, 10–16, 17–29, and >30, respectively, indicate minimal, mild, moderate, and severe depression.

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

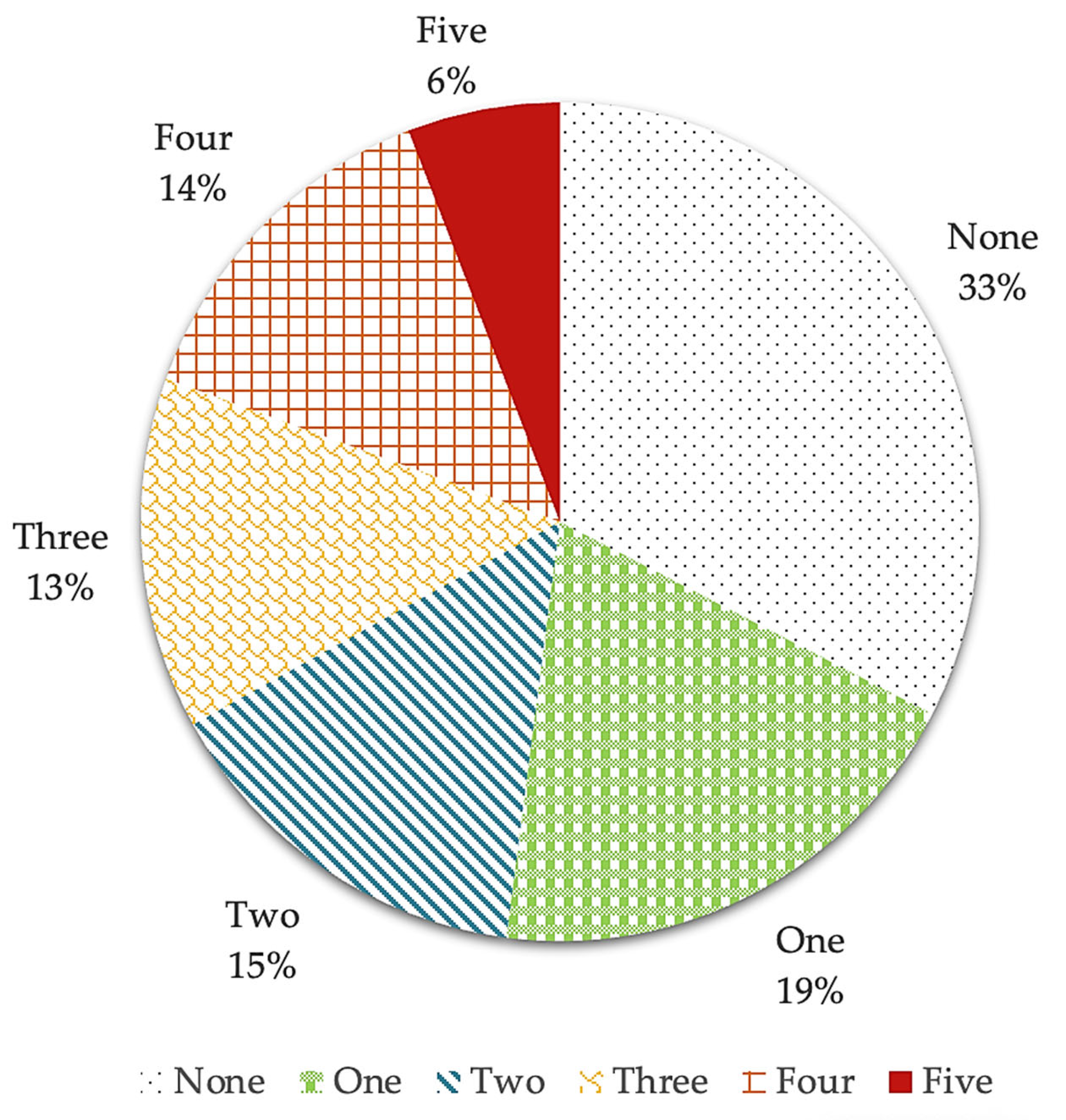

- Sweet eating + hyperphagia + binge eating + food addiction (14.1%);

- Sweet eating + hyperphagia + binge eating + food addiction + night eating (8.7%);

- Sweet eating + hyperphagia (8.1%);

- Sweet eating + hyperphagia + binge eating (5.4%).

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Peeters, A.; Barendregt, J.J.; Willekens, F.; Mackenbach, J.P.; Al Mamun, A.; Bonneux, L.; Janssen, F.; Kunst, A.; Nusselder, W. Obesity in Adulthood and Its Consequences for Life Expectancy: A Life-Table Analysis. Ann. Intern. Med. 2003, 138, 24–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Lancet Gastroenterology & Hepatology. Obesity: Another Ongoing Pandemic. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2021, 6, 411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flegal, K.M.; Graubard, B.I.; Williamson, D.F.; Gail, M.H. Cause-Specific Excess Deaths Associated with Underweight, Overweight, and Obesity. JAMA 2007, 298, 2028–2037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bray, G.A.; Frühbeck, G.; Ryan, D.H.; Wilding, J.P.H. Management of Obesity. Lancet 2016, 387, 1947–1956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, K.D.; Kahan, S. Maintenance of Lost Weight and Long-Term Management of Obesity. Med. Clin. N. Am. 2018, 102, 183–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tak, Y.J.; Lee, S.Y. Long-Term Efficacy and Safety of Anti-Obesity Treatment: Where Do We Stand? Curr. Obes. Rep. 2021, 10, 14–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmaleh-Sachs, A.; Schwartz, J.L.; Bramante, C.T.; Nicklas, J.M.; Gudzune, K.A.; Jay, M. Obesity Management in Adults: A Review. JAMA 2023, 330, 2000–2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garvey, W.T.; Mechanick, J.I. Proposal for a Scientifically Correct and Medically Actionable Disease Classification System (ICD) for Obesity. Obesity 2020, 28, 484–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acosta, A.; Camilleri, M.; Abu Dayyeh, B.; Calderon, G.; Gonzalez, D.; McRae, A.; Rossini, W.; Singh, S.; Burton, D.; Clark, M.M. Selection of Antiobesity Medications Based on Phenotypes Enhances Weight Loss: A Pragmatic Trial in an Obesity Clinic. Obesity 2021, 29, 662–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blüher, M. Metabolically Healthy Obesity. Endocr. Rev. 2020, 41, 405–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.M.; Kushner, R.F. A Proposed Clinical Staging System for Obesity. Int. J. Obes. 2009, 33, 289–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Luz, F.Q.; Sainsbury, A.; Mannan, H.; Touyz, S.; Mitchison, D.; Hay, P. Prevalence of Obesity and Comorbid Eating Disorder Behaviors in South Australia from 1995 to 2015. Int. J. Obes. 2017, 41, 1148–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Succurro, E.; Segura-Garcia, C.; Ruffo, M.; Caroleo, M.; Rania, M.; Aloi, M.; De Fazio, P.; Sesti, G.; Arturi, F. Obese Patients with a Binge Eating Disorder Have an Unfavorable Metabolic and Inflammatory Profile. Medicine 2015, 94, e2098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. DSM-5, 5th ed.; American Psychiatric Publishing: Arlington, VA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Heriseanu, A.I.; Hay, P.; Touyz, S. Grazing Behaviour and Associations with Obesity, Eating Disorders, and Health-Related Quality of Life in the Australian Population. Appetite 2019, 143, 104396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Natale, C.; Lucidi, L.; Montemitro, C.; Pettorruso, M.; Collevecchio, R.; Di Caprio, L.; Giampietro, L.; Aceto, L.; Martinotti, G.; Giannantonio, M. di Gender Differences in the Psychopathology of Obesity: How Relevant Is the Role of Binge Eating Behaviors? Brain Sci. 2022, 12, 955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teodoro, M.C.; Conceição, E.M.; de Lourdes, M.; Alves, J.R.; Neufeld, C.B. Grazing’s Frequency and Associations with Obesity, Psychopathology, and Loss of Control Eating in Clinical and Community Contexts: A Systematic Review. Appetite 2021, 167, 105620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balantekin, K.N.; Grammer, A.C.; Fitzsimmons-Craft, E.E.; Eichen, D.E.; Graham, A.K.; Monterubio, G.E.; Firebaugh, M.L.; Karam, A.M.; Sadeh-Sharvit, S.; Goel, N.J.; et al. Overweight and Obesity Are Associated with Increased Eating Disorder Correlates and General Psychopathology in University Women with Eating Disorders. Eat. Behav. 2021, 41, 101482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Lourdes, M.; Pinto-Bastos, A.; Machado, P.P.P.; Conceição, E. Problematic Eating Behaviors in Patients Undergoing Bariatric Surgery: Studying Their Relationship with Psychopathology. J. Health Psychol. 2022, 27, 1535–1546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caroleo, M.; Primerano, A.; Rania, M.; Aloi, M.; Pugliese, V.; Magliocco, F.; Fazia, G.; Filippo, A.; Sinopoli, F.; Ricchio, M.; et al. A Real World Study on the Genetic, Cognitive and Psychopathological Differences of Obese Patients Clustered According to Eating Behaviours. Eur. Psychiatry 2018, 48, 58–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbone, E.A.; Caroleo, M.; Rania, M.; Calabrò, G.; Staltari, F.A.; de Filippis, R.; Aloi, M.; Condoleo, F.; Arturi, F.; Segura-Garcia, C. An Open-Label Trial on the Efficacy and Tolerability of Naltrexone/Bupropion SR for Treating Altered Eating Behaviours and Weight Loss in Binge Eating Disorder. Eat. Weight. Disord. 2021, 26, 779–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aloi, M.; Liuzza, M.T.; Rania, M.; Carbone, E.A.; de Filippis, R.; Gearhardt, A.N.; Segura-Garcia, C. Using Latent Class Analysis to Identify Different Clinical Profiles According to Food Addiction Symptoms in Obesity with and without Binge Eating Disorder. J. Behav. Addict. 2024, 13, 262–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, C. The Epidemiology and Genetics of Binge Eating Disorder (BED). CNS Spectr. 2015, 20, 522–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, J.F.; Choi, D.L.; Shurdak, J.D.; Krause, E.G.; Fitzgerald, M.F.; Lipton, J.W.; Sakai, R.R.; Benoit, S.C. Central Melanocortins Modulate Mesocorticolimbic Activity and Food Seeking Behavior in the Rat. Physiol. Behav. 2011, 102, 491–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gearhardt, A.N.; White, M.A.; Masheb, R.M.; Morgan, P.T.; Crosby, R.D.; Grilo, C.M. An Examination of the Food Addiction Construct in Obese Patients with Binge Eating Disorder. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2012, 45, 657–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- di Giacomo, E.; Aliberti, F.; Pescatore, F.; Santorelli, M.; Pessina, R.; Placenti, V.; Colmegna, F.; Clerici, M. Disentangling Binge Eating Disorder and Food Addiction: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Eat. Weight. Disord. 2022, 27, 1963–1970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heriseanu, A.I.; Hay, P.; Corbit, L.; Touyz, S. Grazing in Adults with Obesity and Eating Disorders: A Systematic Review of Associated Clinical Features and Meta-Analysis of Prevalence. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2017, 58, 16–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gearhardt, A.N.; Boswell, R.G.; White, M.A. The Association of “Food Addiction” with Disordered Eating and Body Mass Index. Eat. Behav. 2014, 15, 427–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heriseanu, A.I.; Hay, P.; Touyz, S. A Cross-Sectional Examination of Executive Function and Its Associations with Grazing in Persons with Obesity with and without Eating Disorder Features Compared to a Healthy Control Group. Eat. Weight. Disord. 2021, 26, 2491–2501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorflinger, L.M.; Ruser, C.B.; Masheb, R.M. Night Eating among Veterans with Obesity. Appetite 2017, 117, 330–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleator, J.; Judd, P.; James, M.; Abbott, J.; Sutton, C.J.; Wilding, J.P.H. Characteristics and Perspectives of Night-Eating Behaviour in a Severely Obese Population. Clin. Obes. 2014, 4, 30–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- House, E.T.; Lister, N.B.; Seidler, A.L.; Li, H.; Ong, W.Y.; McMaster, C.M.; Paxton, S.J.; Jebeile, H. Identifying Eating Disorders in Adolescents and Adults with Overweight or Obesity: A Systematic Review of Screening Questionnaires. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2022, 55, 1171–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Segura-Garcia, C.; Aloi, M.; Rania, M.; de Filippis, R.; Carbone, E.A.; Taverna, S.; Papaianni, M.C.; Liuzza, M.T.; De Fazio, P. Development, Validation and Clinical Use of the Eating Behaviors Assessment for Obesity (EBA-O). Eat. Weight. Disord. 2022, 27, 2143–2154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Medical Association. WMA declaration of helsinki—Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA 2013, 310, 2191–2194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fairburn, C.G.; Beglin, S.J. Assessment of Eating Disorder Psychopathology: Interview or Self-Report Questionnaire. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 1994, 16, 363–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spielberger, C.; Gorsuch, R.; Lushene, R. STAI Manual for the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory; Consulting Psychologists Press: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Beck, A.T.; Ward, C.H.; Mendelson, M.; Mock, J.; Erbaugh, J. An Inventory for Measuring Depression. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 1961, 4, 561–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabachnick, B.G.; Fidell, L.S. A Guide to Statistical Techniques. In Using Multivariate Statistics; Pearson Education: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2012; Chapter 2; pp. 17–32. [Google Scholar]

- Mooi, E.; Sarstedt, M. Chapter 9: Cluster Analysis. In A Concise Guide to Market Research; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; pp. 237–284. [Google Scholar]

- Gormally, J.; Black, S.; Daston, S.; Rardin, D. The Assessment of Binge Eating Severity among Obese Persons. Addict. Behav. 1982, 7, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palavras, M.A.; Morgan, C.M.; Borges, F.M.B.; Claudino, A.M.; Hay, P.J. An Investigation of Objective and Subjective Types of Binge Eating Episodes in a Clinical Sample of People with Co-Morbid Obesity. J. Eat. Disord. 2013, 1, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbone, E.A.; Aloi, M.; Rania, M.; de Filippis, R.; Quirino, D.; Fiorentino, T.V.; Segura-Garcia, C. The Relationship of Food Addiction with Binge Eating Disorder and Obesity: A Network Analysis Study. Appetite 2023, 190, 107037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şengör, G.; Gezer, C. Food Addiction and Its Relationship with Disordered Eating Behaviours and Obesity. Eat. Weight. Disord. 2019, 24, 1031–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conceição, E.; Vaz, A.; Bastos, A.P.; Ramos, A.; Machado, P. The Development of Eating Disorders after Bariatric Surgery. Eat. Disord. 2013, 21, 275–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandit, R.; De Jong, J.W.; Vanderschuren, L.J.M.J.; Adan, R.A.H. Neurobiology of Overeating and Obesity: The Role of Melanocortins and Beyond. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2011, 660, 28–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Macedo, I.C.; De Freitas, J.S.; Da Silva Torres, I.L. The Influence of Palatable Diets in Reward System Activation: A Mini Review. Adv. Pharmacol. Sci. 2016, 2016, 7238679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heatherton, T.F.; Baumeister, R.F. Binge Eating as Escape from Self-Awareness. Psychol. Bull. 1991, 110, 86–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blackburn, S.; Johnston, L.; Blampied, N.; Popp, D.; Kallen, R. An Application of Escape Theory to Binge Eating. Eur. Eat. Disord. Rev. 2006, 14, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devonport, T.J.; Nicholls, W.; Fullerton, C. A Systematic Review of the Association between Emotions and Eating Behaviour in Normal and Overweight Adult Populations. J. Health Psychol. 2019, 24, 3–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aibao, Z.; Pei, X.; Zhe, T.; Chaochao, P. The Influence of Emotion on Eating Behavior. Adv. Psychol. Sci. 2021, 29, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erlanson-Albertsson, C. How Palatable Food Disrupts Appetite Regulation. Basic Clin. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2005, 97, 61–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rania, M.; Caroleo, M.; Carbone, E.A.; Ricchio, M.; Pelle, M.C.; Zaffina, I.; Condoleo, F.; de Filippis, R.; Aloi, M.; De Fazio, P.; et al. Reactive Hypoglycemia in Binge Eating Disorder, Food Addiction, and the Comorbid Phenotype: Unravelling the Metabolic Drive to Disordered Eating Behaviours. J. Eat. Disord. 2023, 11, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Almeida, R.; Kamath, G.; Cabandugama, P. Food Addiction in Application to Obesity Management. Mo. Med. 2022, 119, 372–378. [Google Scholar]

- Polivy, J.; Herman, C. Etiology of Binge Eating: Psychological Mechanisms. In Binge Eating: Nature, Assessment, and Treatment; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Weinberger, N.A.; Kersting, A.; Riedel-Heller, S.G.; Luck-Sikorski, C. Body Dissatisfaction in Individuals with Obesity Compared to Normal-Weight Individuals: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Obes. Facts 2017, 9, 424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lizana-Calderón, P.; Alvarado, J.M.; Cruzat-Mandich, C.; Díaz-Castrillón, F.; Soto-Núñez, M. Influence of Body Image, Risk of Eating Disorder, Psychological Characteristics, and Mood-Anxious Symptoms on Overweight and Obesity in Chilean Youth. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamamiya, Y.; Desjardins, C.D.; Stice, E. Sequencing of Symptom Emergence in Anorexia Nervosa, Bulimia Nervosa, Binge Eating Disorder, and Purging Disorder in Adolescent Girls and Relations of Prodromal Symptoms to Future Onset of These Eating Disorders. Psychol. Med. 2023, 53, 4657–4665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanofsky-Kraff, M.; Yanovski, S.Z. Eating Disorder or Disordered Eating? Non-Normative Eating Patterns in Obese Individuals. Obes. Res. 2004, 12, 1361–1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodman, E.L.; Breithaupt, L.; Watson, H.J.; Peat, C.M.; Baker, J.H.; Bulik, C.M.; Brownley, K.A. Sweet Taste Preference in Binge-Eating Disorder: A Preliminary Investigation. Eat. Behav. 2018, 28, 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florio, L.; Lassi, D.L.S.; De Azevedo-Marques Perico, C.; Vignoli, N.G.; Torales, J.; Ventriglio, A.; Castaldelli-Maia, J.M. Food Addiction: A Comprehensive Review. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 2022, 210, 874–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stemann Larsen, P.; Nybo Andersen, A.M.; Olsen, E.M.; Kragh Andersen, P.; Micali, N.; Strandberg-Larsen, K. Weight Trajectories and Disordered Eating Behaviours in 11- to 12-Year-Olds: A Longitudinal Study within the Danish National Birth Cohort. Eur. Eat. Disord. Rev. 2019, 27, 436–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barakat, S.; McLean, S.A.; Bryant, E.; Le, A.; Marks, P.; Aouad, P.; Barakat, S.; Boakes, R.; Brennan, L.; Bryant, E.; et al. Risk Factors for Eating Disorders: Findings from a Rapid Review. J. Eat. Disord. 2023, 11, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flayelle, M.; Lannoy, S. Binge Behaviors: Assessment, Determinants, and Consequences. Addict. Behav. Rep. 2021, 14, 100380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Fr | % | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Education | Elementary school | 9 | 4 |

| Middle school I | 55 | 25 | |

| High school II | 107 | 48 | |

| University degree | 40 | 18 | |

| No answer | 13 | 6 | |

| Employment | Unpaid activity | 32 | 14 |

| Employed | 88 | 39 | |

| Unemployed | 48 | 21 | |

| Student | 36 | 16 | |

| On pension | 6 | 3 | |

| No answer | 14 | 6 | |

| Civil status | Single | 74 | 33 |

| Married | 123 | 55 | |

| Divorced | 12 | 5 | |

| Widowers | 1 | 1 | |

| No Answer | 14 | 6 | |

| Early childhood obesity | Yes | 57 | 25 |

| Late childhood obesity | Yes | 107 | 48 |

| Adolescent obesity | Yes | 141 | 63 |

| BMI category | I (30–34.99 kg/m2) | 34 | 15 |

| II (35–39.99 kg/m2) | 76 | 34 | |

| III (≥40 kg/m2) | 114 | 51 |

| Mean | SD | Min | Max | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EDE-Q | R | 2.0 | 1.5 | 0 | 6 |

| EC | 2.2 | 1.7 | 0 | 6 | |

| SC | 4.1 | 1.6 | 0 | 6 | |

| WC | 3.5 | 1.5 | 0 | 6 | |

| Total | 3.0 | 1.3 | 0 | 5.8 | |

| BDI-II | Total | 19.2 | 13.7 | 0 | 54 |

| STAI-S | Total | 47.5 | 14.2 | 20 | 80 |

| STAI-T | Total | 49.1 | 14.9 | 20 | 79 |

| EBA-O | NE | 1.5 | 1.9 | 0 | 7 |

| FA | 2.7 | 2.1 | 0 | 7 | |

| SE | 3.9 | 2.3 | 0 | 7 | |

| H | 2.8 | 2.2 | 0 | 7 | |

| BE | 2.7 | 2.4 | 0 | 7 | |

| Total | 2.7 | 1.7 | 0.05 | 7 |

| Dependent Variable | F | p | η2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| BDI-II | 14.039 | <0.001 | 0.310 |

| STAI-S | 10.194 | <0.001 | 0.246 |

| EDE-Q R | 1.529 | 0.184 | 0.047 |

| EDE-Q EC | 30.967 | <0.001 | 0.498 |

| EDE-Q SC | 9.860 | <0.001 | 0.240 |

| EDE-Q WC | 14.746 | <0.001 | 0.321 |

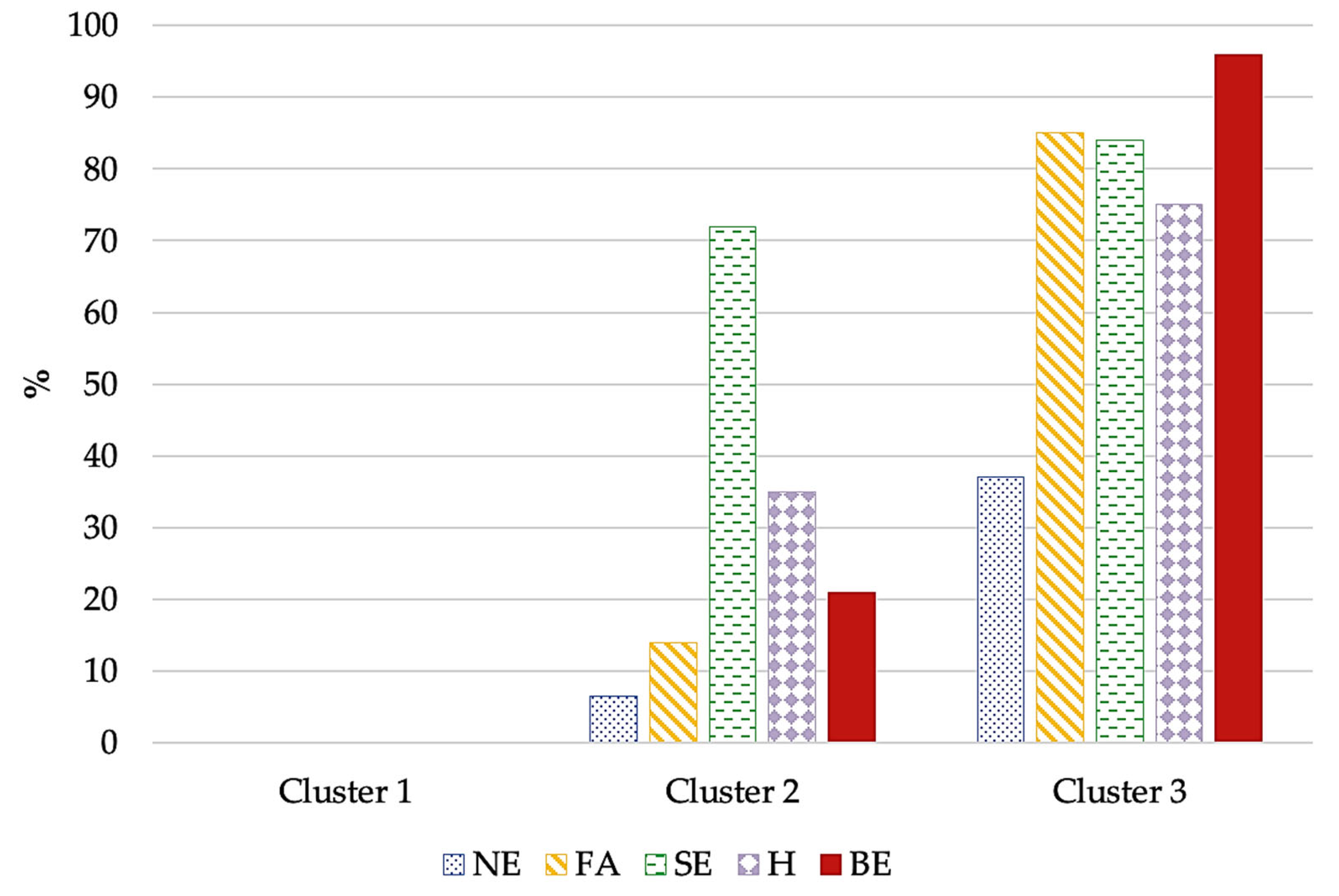

| Cluster 1 N = 73 | Cluster 2 N = 78 | Cluster 3 N = 73 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Statistics | p | Effect Size | ||

| Number of AEBs | 0 | 0 | 1.5 | 0.6 | 3.8 | 0.8 | F = 930.999 | <0.001 | η2 = 0.894 | |

| Age | 40.5 | 12.7 | 40.4 | 13.7 | 37.3 | 14.1 | F = 1.230 | 0.294 | ||

| BMI | 42.8 | 8.4 | 41.7 | 6.1 | 40.3 | 6.6 | F = 2.288 | 0.104 | ||

| Sex § | Female | 59 | 81 | 64 | 82 | 59 | 81 | χ2 = 0.050 | 0.975 | |

| Male | 12 | 19 | 14 | 18 | 14 | 19 | ||||

| Early childhood obesity § | 14 | 21 | 26 | 36 | 17 | 26 | χ2 = 3.960 | 0.138 | ||

| Late childhood obesity § | 24 | 36 | 47 | 64 | 36 | 54 | χ2 = 11.579 | 0.003 | V = 0.237 | |

| Adolescent obesity § | 36 | 53 | 58 | 81 | 47 | 70 | χ2 = 12.468 | 0.002 | V = 0.245 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Carbone, E.A.; Rania, M.; D’Onofrio, E.; Quirino, D.; de Filippis, R.; Rotella, L.; Aloi, M.; Fiorentino, V.T.; Murphy, R.; Segura-Garcia, C. The Greater the Number of Altered Eating Behaviors in Obesity, the More Severe the Psychopathology. Nutrients 2024, 16, 4378. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16244378

Carbone EA, Rania M, D’Onofrio E, Quirino D, de Filippis R, Rotella L, Aloi M, Fiorentino VT, Murphy R, Segura-Garcia C. The Greater the Number of Altered Eating Behaviors in Obesity, the More Severe the Psychopathology. Nutrients. 2024; 16(24):4378. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16244378

Chicago/Turabian StyleCarbone, Elvira Anna, Marianna Rania, Ettore D’Onofrio, Daria Quirino, Renato de Filippis, Lavinia Rotella, Matteo Aloi, Vanessa Teresa Fiorentino, Rinki Murphy, and Cristina Segura-Garcia. 2024. "The Greater the Number of Altered Eating Behaviors in Obesity, the More Severe the Psychopathology" Nutrients 16, no. 24: 4378. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16244378

APA StyleCarbone, E. A., Rania, M., D’Onofrio, E., Quirino, D., de Filippis, R., Rotella, L., Aloi, M., Fiorentino, V. T., Murphy, R., & Segura-Garcia, C. (2024). The Greater the Number of Altered Eating Behaviors in Obesity, the More Severe the Psychopathology. Nutrients, 16(24), 4378. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16244378