Association of Social Jetlag with the Dietary Quality Among Korean Workers: Findings from a Nationwide Survey

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

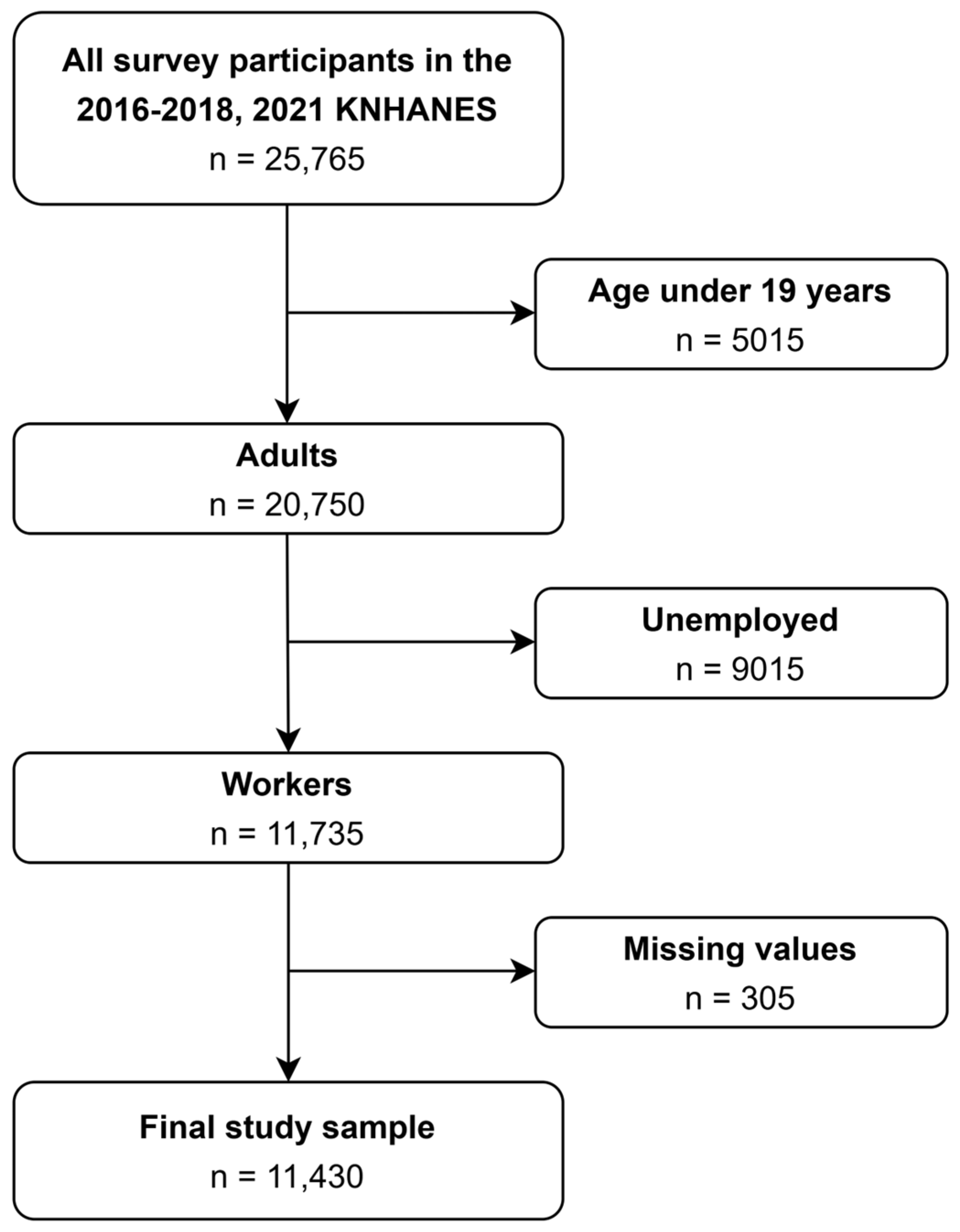

2.1. Study Population

2.2. Variables

2.2.1. Social Jetlag (Exposure)

2.2.2. Dietary Quality Assessment (Outcome)

2.2.3. Covariates

2.3. Aanlysis Plan

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Roenneberg, T.; Pilz, L.K.; Zerbini, G.; Winnebeck, E.C. Chronotype and Social Jetlag: A (Self-) Critical Review. Biology 2019, 8, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roenneberg, T. How can social jetlag affect health? Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2023, 19, 383–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wittmann, M.; Dinich, J.; Merrow, M.; Roenneberg, T. Social jetlag: Misalignment of biological and social time. Chronobiol. Int. 2006, 23, 497–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caliandro, R.; Streng, A.A.; van Kerkhof, L.W.M.; van der Horst, G.T.J.; Chaves, I. Social Jetlag and Related Risks for Human Health: A Timely Review. Nutrients 2021, 13, 4543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, J.; Jang, T.W.; Lee, H.E.; Cho, S.S.; Kang, M.Y. Social jetlag and risk of depression: Results from the Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. J. Affect. Disord. 2023, 323, 562–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, E.J.; Cho, S.S.; Lee, H.E.; Min, J.; Jang, T.W.; Kang, M.Y. Association between social jetlag and self-rated health: Evidence from Korean representative working population. Sleep Med. 2023, 114, 86–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, S.S.; Chung, B.H.; Lee, H.E.; Kang, M.Y. Association between social jetlag and chronic kidney disease among the Korean working population. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 5998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arab, A.; Karimi, E.; Garaulet, M.; Scheer, F. Social jetlag and obesity: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes. Rev. 2023, 25, e13664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, Z.; Akter, S.; Kochi, T.; Hu, H.; Eguchi, M.; Yamaguchi, M.; Kuwahara, K.; Kabe, I.; Mizoue, T. Association of social jetlag with metabolic syndrome among Japanese working population: The Furukawa Nutrition and Health Study. Sleep Med. 2018, 51, 53–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouman, E.J.; Beulens, J.W.J.; Groeneveld, L.; de Kruijk, R.S.; Schoonmade, L.J.; Remmelzwaal, S.; Elders, P.J.M.; Rutters, F. The association between social jetlag and parameters of metabolic syndrome and type 2 diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Sleep Res. 2023, 32, e13770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arab, A.; Karimi, E.; Garaulet, M.; Scheer, F. Social jetlag and dietary intake: A systematic review. Sleep Med. Rev. 2023, 71, 101820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suikki, T.; Maukonen, M.; Partonen, T.; Jousilahti, P.; Kanerva, N.; Mannisto, S. Association between social jet lag, quality of diet and obesity by diurnal preference in Finnish adult population. Chronobiol. Int. 2021, 38, 720–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, F.; Fu, J.; Xu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Qiu, N.; Ding, K.; Zeng, J.; Moore, J.B.; Li, R. Associations of Social Jetlag with Dietary Behavior, Physical Activity and Obesity among Chinese Adolescents. Nutrients 2022, 14, 510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Khatib, H.; Dikariyanto, V.; Bermingham, K.M.; Gibson, R.; Hall, W.L. Short sleep and social jetlag are associated with higher intakes of non-milk extrinsic sugars, and social jetlag is associated with lower fibre intakes in those with adequate sleep duration: A cross-sectional analysis from the National Diet and Nutrition Survey Rolling Programme (Years 1–9). Public Health Nutr. 2022, 25, 2570–2581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cetiner, O.; Yildirim, G.; Kalyoncu, Z.B. Social Jetlag Is Associated with the Frequency of Consumption of Sugar-Sweetened Beverages and a High BMI Percentile in Adolescents: Results of the Cross-Sectional Family Life, Activity, Sun, Health, and Eating (FLASHE) Study. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet 2021, 121, 1721–1731.e1721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeron-Rugerio, M.F.; Cambras, T.; Izquierdo-Pulido, M. Social Jet Lag Associates Negatively with the Adherence to the Mediterranean Diet and Body Mass Index among Young Adults. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, Z.; Nanri, A.; Akter, S.; Kuwahara, K.; Miki, T.; Van Hoang, D.; Yamamoto, S.; Fukunaga, A.; Kochi, T.; Eguchi, M.; et al. Relationship of chronotype and social jetlag with adherence to the Japanese dietary guidelines among workers. Chronobiol. Int. 2022, 39, 1195–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almoosawi, S.; Palla, L.; Walshe, I.; Vingeliene, S.; Ellis, J.G. Long Sleep Duration and Social Jetlag Are Associated Inversely with a Healthy Dietary Pattern in Adults: Results from the UK National Diet and Nutrition Survey Rolling Programme Y1(-)4. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodur, M.; Baspinar, B.; Ozcelik, A.O. A cross-sectional evaluation of the relationship between social jetlag and diet quality. Chronobiol. Int. 2021, 38, 1557–1568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshizaki, T.; Togo, F. Objectively measured chronotype and social jetlag are associated with habitual dietary intake in undergraduate students. Nutr. Res. 2021, 90, 36–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.; Kim, J.M. The association of the Korean Healthy Eating Index with chronic conditions in middle-aged single-person households. Nutr. Res. Pract. 2023, 17, 316–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, Y.J.; Yu, K.W.; Lee, K.H.; Jang, K.I. Association of the Healthy Eating Index with Metabolic Abnormalities among Middle-Aged Adults Living in Single-Person Households in Korea. Nutrients 2021, 13, 3937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, S.; Lee, S. Relation between the Total Diet Quality based on Korean Healthy Eating Index and the Incidence of Metabolic Syndrome Constituents and Metabolic Syndrome among a Prospective Cohort of Korean Adults. Korean J. Community Nutr. 2020, 25, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kweon, S.; Kim, Y.; Jang, M.J.; Kim, Y.; Kim, K.; Choi, S.; Chun, C.; Khang, Y.H.; Oh, K. Data resource profile: The Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES). Int. J. Epidemiol. 2014, 43, 69–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, K.; Kim, Y.; Kweon, S.; Kim, S.; Yun, S.; Park, S.; Lee, Y.K.; Kim, Y.; Park, O.; Jeong, E.K. Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 20th anniversary: Accomplishments and future directions. Epidemiol. Health 2021, 43, e2021025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamura, N.; Okamura, K. Social jetlag as a predictor of depressive symptoms among Japanese adolescents: Evidence from the Adolescent Sleep Health Epidemiological Cohort. Sleep Health 2023, 9, 638–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Cajochen, C.; Khatami, R. Social Jetlag and Chronotypes in the Chinese Population: Analysis of Data Recorded by Wearable Devices. J. Med. Internet Res. 2019, 21, e13482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, S.; Park, S.; Yook, S.M.; Kim, K.; Shim, J.E.; Hwang, J.Y.; Oh, K. Development of the Korean Healthy Eating Index for adults, based on the Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Nutr. Res. Pract. 2022, 16, 233–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, G.; Park, D.; Lee, J.; Kim, R.; Subramanian, S.V.; Oh, H.; Shin, M.J. Trends in Diet Quality and Cardiometabolic Risk Factors Among Korean Adults, 2007–2018. JAMA Netw. Open 2022, 5, e2218297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, Y.S.; Oh, S.W. Relationship between psychological distress and the adherence to the Korean healthy eating index (KHEI): The Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES) 2013 and 2015. Nutr. Res. Pract. 2021, 15, 516–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y. The Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES): Current status and challenges. Epidemiol. Health 2014, 36, e2014002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kweon, S.; Park, J.Y.; Park, M.; Kim, Y.; Yeon, S.Y.; Yoon, L.; Yun, S.; Park, S.; Yang, J.E.; Kim, Y.; et al. Trends in food and nutrient intake over 20 years: Findings from the 1998-2018 Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Epidemiol. Health 2021, 43, e2021027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rural Development Administration. Standard Food Composition Table (8th Revision); Rural Development Administration: Wanju-gun, Republic of Korea, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Jansen, E.C.; Baylin, A.; Cantoral, A.; Tellez Rojo, M.M.; Burgess, H.J.; O’Brien, L.M.; Torres Olascoaga, L.; Peterson, K.E. Dietary Patterns in Relation to Prospective Sleep Duration and Timing among Mexico City Adolescents. Nutrients 2020, 12, 2305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, I.; Min, J. Working hours and the regulations in Korea. Ann. Occup. Environ. Med. 2023, 35, e18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bull, F.C.; Al-Ansari, S.S.; Biddle, S.; Borodulin, K.; Buman, M.P.; Cardon, G.; Carty, C.; Chaput, J.P.; Chastin, S.; Chou, R.; et al. World Health Organization 2020 guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behaviour. Br. J. Sports Med. 2020, 54, 1451–1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozaki, I.; Nishijima, M.; Konishi, M. Feasibility and Acceptability of Policies and Environmental Strategies for Improving Physical Activity and Healthy Eating in Japanese Small and Medium Corporations. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2023, 65, 39–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zerbini, G.; Kantermann, T.; Merrow, M. Strategies to decrease social jetlag: Reducing evening blue light advances sleep and melatonin. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2020, 51, 2355–2366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bermingham, K.M.; Stensrud, S.; Asnicar, F.; Valdes, A.M.; Franks, P.W.; Wolf, J.; Hadjigeorgiou, G.; Davies, R.; Spector, T.D.; Segata, N.; et al. Exploring the relationship between social jetlag with gut microbial composition, diet and cardiometabolic health, in the ZOE PREDICT 1 cohort. Eur. J. Nutr. 2023, 62, 3135–3147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaput, J.P.; McHill, A.W.; Cox, R.C.; Broussard, J.L.; Dutil, C.; da Costa, B.G.G.; Sampasa-Kanyinga, H.; Wright, K.P., Jr. The role of insufficient sleep and circadian misalignment in obesity. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2023, 19, 82–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spiegel, K.; Tasali, E.; Penev, P.; Van Cauter, E. Brief communication: Sleep curtailment in healthy young men is associated with decreased leptin levels, elevated ghrelin levels, and increased hunger and appetite. Ann. Intern. Med. 2004, 141, 846–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaput, J.P. Sleep patterns, diet quality and energy balance. Physiol. Behav. 2014, 134, 86–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Overall | Social Jetlag (min) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <0 | 0–59 | 60–119 | ≥120 | ||

| n = 11,430 | n = 542 | n = 7093 | n = 2645 | n = 1150 | |

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 5704 (58.3) | 281 (60.3) | 3635 (59.4) | 1205 (55.0) | 583 (58.9) |

| Female | 5726 (41.7) | 261 (39.7) | 3458 (40.6) | 1440 (45.0) | 567 (41.1) |

| Age | |||||

| <40 | 3258 (36.2) | 144 (35.2) | 1413 (26.6) | 1023 (44.4) | 678 (66.2) |

| 40–49 | 2627 (24.8) | 110 (22.2) | 1447 (23.6) | 829 (31.1) | 241 (19.0) |

| 50–59 | 2592 (23.1) | 133 (24.7) | 1825 (27.8) | 485 (17.7) | 149 (11.3) |

| ≥60 | 2953 (15.8) | 155 (17.9) | 2408 (22.1) | 308 (6.8) | 82 (3.6) |

| Education level | |||||

| Middle school or below | 2724 (16.4) | 164 (22.5) | 2146 (21.6) | 305 (8.2) | 109 (5.9) |

| High school | 3742 (34.7) | 196 (40.1) | 2226 (33.4) | 868 (34.2) | 452 (40.1) |

| College or above | 4964 (48.9) | 182 (37.4) | 2721 (45.0) | 1472 (57.7) | 589 (54.0) |

| Income level | |||||

| Lowest | 2347 (20.4) | 115 (20.8) | 1501 (21.2) | 487 (18.9) | 244 (19.8) |

| Low | 2993 (25.9) | 150 (25.8) | 1873 (25.9) | 668 (25.4) | 302 (27.3) |

| High | 3059 (26.7) | 160 (31.0) | 1872 (26.3) | 726 (27.3) | 301 (26.2) |

| Highest | 3031 (26.9) | 117 (22.4) | 1847 (26.7) | 764 (28.4) | 303 (26.8) |

| Marital status | |||||

| Married | 8219 (67.9) | 367 (64.6) | 5455 (74.7) | 1886 (67.1) | 511 (38.7) |

| Unmarried | 1990 (23.8) | 97 (24.5) | 745 (15.2) | 594 (28.1) | 554 (56.1) |

| Others | 1,221 (8.2) | 78 (10.9) | 893 (10.1) | 165 (4.8) | 85 (5.2) |

| Job | |||||

| White collar | 4597 (44.2) | 158 (31.7) | 2470 (39.8) | 1414 (54.0) | 555 (50.1) |

| Service/sales worker | 2392 (21.2) | 153 (30.1) | 1545 (22.5) | 466 (17.1) | 228 (20.1) |

| Blue collar | 4441 (34.6) | 231 (38.2) | 3078 (37.7) | 765 (28.9) | 367 (29.8) |

| Working hours | |||||

| ≤52 h | 9456 (82.3) | 399 (73.5) | 5826 (81.6) | 2273 (85.6) | 958 (83.1) |

| >52 h | 1974 (17.7) | 143 (26.5) | 1267 (18.4) | 372 (14.4) | 192 (16.9) |

| Shift work | |||||

| No | 9668 (83.5) | 326 (60.3) | 6070 (84.2) | 2345 (87.6) | 927 (81.1) |

| Yes | 1762 (16.5) | 216 (39.7) | 1023 (15.8) | 300 (12.4) | 223 (18.9) |

| Chronic condition | |||||

| No | 7217 (68.1) | 315 (65.1) | 4066 (62.5) | 1930 (75.0) | 906 (81.6) |

| Yes | 4213 (31.9) | 227 (34.9) | 3027 (37.5) | 715 (25.0) | 244 (18.4) |

| Current smoking | |||||

| No | 9170 (76.3) | 424 (75.1) | 5801 (78.2) | 2134 (76.7) | 811 (67.2) |

| Yes | 2260 (23.7) | 118 (24.9) | 1292 (21.8) | 511 (23.3) | 339 (32.8) |

| Physical activity | |||||

| No | 6365 (52.1) | 301 (51.8) | 4156 (54.8) | 1343 (48.5) | 565 (46.7) |

| Yes | 5065 (47.9) | 241 (48.2) | 2937 (45.2) | 1302 (51.5) | 585 (53.3) |

| Obesity | |||||

| No | 7323 (63.3) | 326 (58.8) | 4467 (62.3) | 1777 (65.6) | 753 (65.1) |

| Yes | 4107 (36.7) | 216 (41.2) | 2626 (37.7) | 868 (34.4) | 397 (34.9) |

| Percieved stress | |||||

| No | 8294 (71.6) | 380 (68.3) | 5309 (73.8) | 1878 (71.1) | 727 (63.0) |

| Yes | 3136 (28.4) | 162 (31.7) | 1784 (26.2) | 767 (28.9) | 423 (37.0) |

| Score | Overall | Social Jetlag (min) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <0 | 0–59 | 60–119 | ≥120 | |||

| Range | n = 11,430 | n = 542 | n = 7093 | n = 2645 | n = 1150 | |

| Total KHEI score | 0–100 | 60.9 ± 13.4 | 60.0 ± 13.6 | 62.4 ± 13.2 | 60.0 ± 13.3 | 56.3 ± 13.4 |

| Adequacy component | ||||||

| Total adequacy score | 0–55 | 29.8 ± 10.5 | 28.7 ± 10.9 | 30.9 ± 10.3 | 29.0 ± 10.4 | 26.7 ± 10.2 |

| Have breakfast | 0–10 | 6.6 ± 4.1 | 6.4 ± 4.2 | 7.3 ± 3.9 | 6.0 ± 4.1 | 4.9 ± 4.1 |

| Mixed grains intake | 0–5 | 1.8 ± 2.1 | 1.8 ± 2.1 | 2.0 ± 2.1 | 1.6 ± 2.0 | 1.3 ± 1.9 |

| Total fruits intake | 0–5 | 1.9 ± 2.1 | 1.7 ± 2.0 | 2.1 ± 2.2 | 1.8 ± 2.1 | 1.4 ± 2.0 |

| Fresh fruits intake | 0–5 | 2.1 ± 2.3 | 1.9 ± 2.3 | 2.3 ± 2.4 | 2.0 ± 2.3 | 1.6 ± 2.2 |

| Total vegetables intake | 0–5 | 3.5 ± 1.5 | 3.5 ± 1.5 | 3.6 ± 1.4 | 3.4 ± 1.5 | 3.2 ± 1.5 |

| Vegetables intake excluding Kimchi and pickled vegetables intake | 0–5 | 3.2 ± 1.6 | 3.1 ± 1.6 | 3.3 ± 1.6 | 3.1 ± 1.6 | 3.0 ± 1.6 |

| Meat, fish, eggs, and beans intake | 0–10 | 7.4 ± 2.9 | 7.3 ± 3.1 | 7.3 ± 3.0 | 7.6 ± 2.9 | 7.5 ± 2.9 |

| Milk and milk products intake | 0–10 | 3.3 ± 4.4 | 3.0 ± 4.3 | 3.2 ± 4.4 | 3.5 ± 4.5 | 3.7 ± 4.5 |

| Moderation component | ||||||

| Total moderation score | 0–30 | 21.9 ± 6.1 | 21.9 ± 6.1 | 22.3 ± 5.9 | 21.4 ± 6.1 | 20.5 ± 6.2 |

| Percentage of energy from saturated fatty acid | 0–10 | 7.0 ± 4.1 | 7.0 ± 4.1 | 7.3 ± 4.0 | 6.6 ± 4.3 | 6.2 ± 4.4 |

| Sodium intake | 0–10 | 6.5 ± 3.3 | 6.3 ± 3.4 | 6.5 ± 3.3 | 6.4 ± 3.3 | 6.3 ± 3.4 |

| Percentage of energy from sweets, beverages, and alcoholic drinks | 0–10 | 8.5 ± 3.0 | 8.6 ± 3.0 | 8.5 ± 3.0 | 8.4 ± 3.1 | 8.1 ± 3.4 |

| Energy balance component | ||||||

| Total energy balance score | 0–15 | 9.3 ± 4.6 | 9.4 ± 4.7 | 9.2 ± 4.7 | 9.6 ± 4.5 | 9.1 ± 4.8 |

| Percentage of energy intake from carbohydrate | 0–5 | 2.7 ± 2.1 | 2.8 ± 2.1 | 2.6 ± 2.1 | 2.9 ± 2.1 | 2.7 ± 2.1 |

| Percentage of energy intake from fat | 0–5 | 3.5 ± 2.1 | 3.5 ± 2.0 | 3.4 ± 2.1 | 3.6 ± 2.0 | 3.5 ± 2.1 |

| Energy intake | 0–5 | 3.1 ± 2.2 | 3.1 ± 2.2 | 3.1 ± 2.2 | 3.1 ± 2.2 | 2.8 ± 2.3 |

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| β (95% CI) | β (95% CI) | β (95% CI) | |

| Total KHEI score a | |||

| Social jetlag | |||

| <0 min | −2.38 (−3.72, −1.04) | −1.56 (−2.84, −0.29) | −1.03 (−2.27, 0.21) |

| 0–59 min | 0.00 (0.00, 0.00) | 0.00 (0.00, 0.00) | 0.00 (0.00, 0.00) |

| 60–119 min | −2.43 (−3.12, −1.73) | −0.35 (−1.03, 0.33) | −0.54 (−1.19, 0.12) |

| ≥120 min | −6.09 (−7.05, −5.14) | −2.38 (−3.33, −1.43) | −1.23 (−2.16, −0.30) |

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |

| OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | |

| Poor dietary quality b | |||

| Social jetlag | |||

| <0 min | 1.48 (1.18, 1.86) | 1.35 (1.06, 1.71) | 1.24 (0.96, 1.60) |

| 0–59 min | 1.00 (1.00, 1.00) | 1.00 (1.00, 1.00) | 1.00 (1.00, 1.00) |

| 60–119 min | 1.43 (1.26, 1.62) | 1.08 (0.95, 1.24) | 1.12 (0.97, 1.28) |

| ≥120 min | 2.31 (1.99, 2.68) | 1.45 (1.24, 1.69) | 1.27 (1.08, 1.50) |

| Predicted Values of KHEI | Predicted Probability of Poor Dietary Quality | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Social Jetlag (X) | Predicted Value (Y) 95% CI | Social Jetlag | Predicted Value (Y) 95% CI | |

| Highest point | 18 min | 62.6 (62.2, 63.0) | 125 min | 0.22 (0.20, 0.24) |

| Lowest point | 210 min | 61.4 (60.6, 62.2.) | 10 min | 0.18 (0.17, 0.20) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Baek, S.-U.; Yoon, J.-H. Association of Social Jetlag with the Dietary Quality Among Korean Workers: Findings from a Nationwide Survey. Nutrients 2024, 16, 4091. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16234091

Baek S-U, Yoon J-H. Association of Social Jetlag with the Dietary Quality Among Korean Workers: Findings from a Nationwide Survey. Nutrients. 2024; 16(23):4091. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16234091

Chicago/Turabian StyleBaek, Seong-Uk, and Jin-Ha Yoon. 2024. "Association of Social Jetlag with the Dietary Quality Among Korean Workers: Findings from a Nationwide Survey" Nutrients 16, no. 23: 4091. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16234091

APA StyleBaek, S.-U., & Yoon, J.-H. (2024). Association of Social Jetlag with the Dietary Quality Among Korean Workers: Findings from a Nationwide Survey. Nutrients, 16(23), 4091. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16234091