Online Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy-Based Nutritional Intervention via Instagram for Overweight and Obesity

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

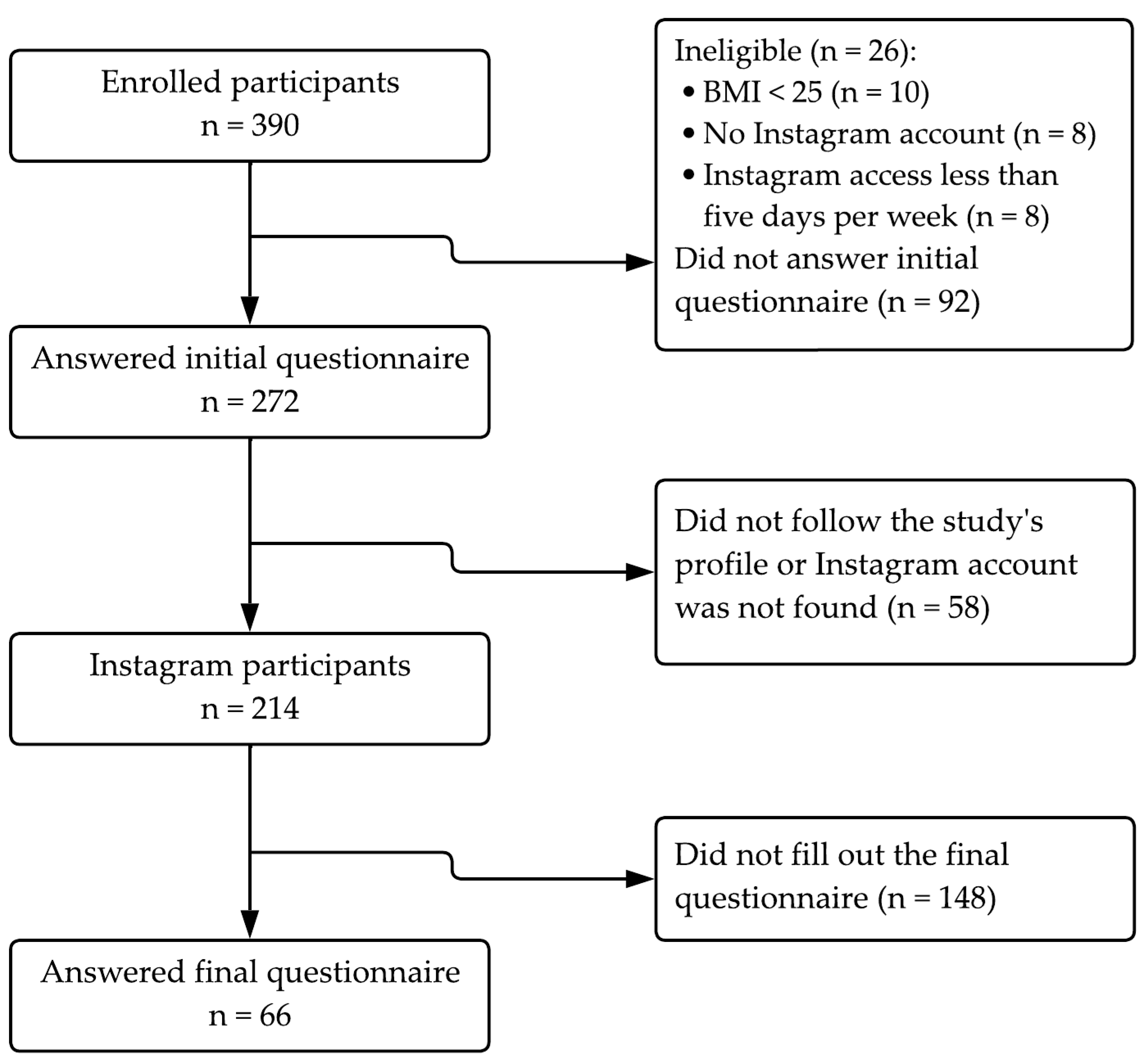

2.1. Study Design and Participants

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Intervention Protocol

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Obesity Federation. World Obesity Atlas 2024. Available online: https://data.worldobesity.org/publications/WOF-Obesity-Atlas-v7.pdf (accessed on 10 May 2024).

- Wang, Y.C.; McPherson, K.; Marsh, T.; Gortmaker, S.L.; Brown, M. Health and economic burden of the projected obesity trends in the USA and the UK. Lancet 2011, 378, 815–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahmoud, R.; Kimonis, V.; Butler, M.G. Genetics of Obesity in Humans: A Clinical Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 11005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lingvay, I.; Cohen, R.V.; Roux, C.W.L.; Sumithran, P. Obesity in adults. Lancet 2024, 404, 972–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spring, B.; Champion, K.E.; Acabchuk, R.; Hennessy, E.A. Self-regulatory behavior change techniques in interventions to promote healthy eating, physical activity, or weight loss: A meta-review. Health Psychol. Rev. 2021, 15, 508–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dalle Grave, R.; Sartirana, M.; Calugi, S. Personalized cognitive-behavioral therapy for obesity (CBT-OB): Theory, strategies, and procedures. Biopsychosoc. Med. 2020, 14, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallis, T.M.; Macklin, D.; Russell-Mayhew, S. Canadian Adult Obesity Clinical Practice Guidelines: Effective Psychological and Behavioural Interventions in Obesity Management. Available online: https://obesitycanada.ca/guidelines/behavioural (accessed on 21 April 2024).

- Spahn, J.M.; Reeves, R.S.; Keim, K.S.; Laquatra, I.; Kellogg, M.; Jortberg, B.; Clark, N.A. State of the evidence regarding behavior change theories and strategies in nutrition counseling to facilitate health and food behavior change. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2010, 110, 879–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, G.D.; Makris, A.P.; Bailer, B.A. Behavioral treatment of obesity. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2005, 82, 230S–235S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalle Grave, R.; Calugi, S.; Gavasso, I.; El Ghoch, M.; Marchesini, G. A randomized trial of energy-restricted high-protein versus high-carbohydrate, low-fat diet in morbid obesity. Obesity 2013, 21, 1774–1781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, L.E.; Soliz, S.; Xu, J.J.; Young, S.D. A review of social media analytic tools and their applications to evaluate activity and engagement in online sexual health interventions. Prev. Med. Rep. 2020, 19, 101158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klassen, K.M.; Douglass, C.H.; Brennan, L.; Truby, H.; Lim, M.S.C. Social media use for nutrition outcomes in young adults: A mixed-methods systematic review. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2018, 15, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karim, F.; Oyewande, A.A.; Abdalla, L.F.; Chaudhry Ehsanullah, R.; Khan, S. Social Media Use and Its Connection to Mental Health: A Systematic Review. Cureus 2020, 12, e8627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hruska, J.; Maresova, P. Use of Social Media Platforms among Adults in the United States—Behavior on Social Media. Societies 2020, 10, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giustini, D.; Ali, S.M.; Fraser, M.; Kamel Boulos, M.N. Effective uses of social media in public health and medicine: A systematic review of systematic reviews. Online J. Public. Health Inform. 2018, 10, e215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Welch, V.; Petkovic, J.; Pardo Pardo, J.; Rader, T.; Tugwell, P. Interactive social media interventions to promote health equity: An overview of reviews. Health Promot. Chronic Dis. Prev. Can. 2016, 36, 63–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutz, C.S.; Zanon, C. Revision of the adaptation, validation, and normalization of the Rosenberg self-esteem scale. Aval. Psicol. 2011, 10, 41–49. [Google Scholar]

- Freitas, S.; Lopes, C.S.; Coutinho, W.; Appolinario, J.C. Translation and adaptation into Portuguese of the Binge-Eating Scale. Rev. Bras. Psiquiatr. 2001, 23, 215–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natacci, L.C.; Ferreira Júnior, M. The Three Factor Eating Questionnaire—R21: Tradução para o Português e Aplicação em Mulheres Brasileiras. Rev. Nutr. 2011, 24, 383–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorenstein, C.; Andrade, L.H.S.G. Validation of a Portuguese Version of the Beck Depression Inventory and State-Trait Anxiety Inventory in Brazilian Subjects. Braz. J. Med. Biol. Res. 1996, 29, 453–457. [Google Scholar]

- Dias, J.C.R.; Silva, W.R.; Maroco, J.; Campos, J.A.D.B. Perceived Stress Scale Applied to College Students: Validation Study. Psychol. Community Health 2015, 4, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, M. Society and the Adolescent Self-Image, 2nd ed.; Wesleyan University Press: Middletown, CT, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Gormally, J.I.M.; Black, S.; Daston, S.; Rardin, D. The assessment of binge eating severity among obese persons. Addict. Behav. 1982, 7, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stunkard, A.J.; Messick, S. The Three-Factor Eating Questionnaire to measure dietary restraint, disinhibition, and hunger. J. Psychosom. Res. 1985, 29, 71–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spielberger, C.D.; Gorsuch, R.L.; Lushene, R.E. Manual for the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory; Consulting Psychologists Press: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Goodyear, V.A.; Wood, G.; Skinner, B.; Thompson, J.L. The effect of social media interventions on physical activity and dietary behaviors in young people and adults: A systematic review. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2021, 18, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Social Insider. Instagram Analytics. Available online: https://www.socialinsider.io/ (accessed on 9 June 2023).

- The Bazaar Voice. Instagram Metrics. Available online: https://www.bazaarvoice.com/blog/key-instagram-metrics/ (accessed on 9 June 2023).

- Mifflin, M.D.; St Jeor, S.T.; Hill, L.A.; Scott, B.J.; Daugherty, S.A.; Koh, Y.O. A new predictive equation for resting energy expenditure in healthy individuals. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1990, 51, 241–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beck, J.S.; Beck, A.T. Cognitive Behavior Therapy: Basics and Beyond, 3rd ed.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Knapp, P. Terapia Cognitivo-Comportamental na Prática Psiquiátrica, 1st ed.; Artmed: Porto Alegre, Brasil, 2004; 520p, ISBN 978-8536302898. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper, Z.; Fairburn, C.G. A new cognitive behavioural approach to the treatment of obesity. Behav. Res. Ther. 2001, 39, 499–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beck, J.S.; Busis, D.B. The Diet Trap Solution: Train Your Brain to Lose Weight and Keep It Off for Good; HarperCollins Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Prochaska, J.O.; Norcross, J.; Diclemente, C.E. Changing for Good; HarperCollins Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Forcano, L.; Mata, F.; de la Torre, R.; Verdejo-Garcia, A. Cognitive and neuromodulation strategies for unhealthy eating and obesity: Systematic review and discussion of neurocognitive mechanisms. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2018, 87, 161–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, S.; Ru, Y.; Wang, J.; Yang, H.; Xu, Y.; Zhou, Q.; Pan, H.; Wang, M. Effects of episodic future thinking in health behaviors for weight loss: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2024, 152, 104667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dogan, B.G.; Tengilimoglu-Metin, M.M. Does mindful eating affect the diet quality of adults? Nutrition 2023, 110, 112010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. A power primer. Psychol. Bull. 1992, 112, 155–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loh, Y.L.; Yaw, Q.P.; Lau, Y. Social media-based interventions for adults with obesity and overweight: A meta-analysis and meta-regression. Int. J. Obes. 2023, 47, 606–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacob, A.; Moullec, G.; Lavoie, K.L.; Laurin, C.; Cowan, T.; Tisshaw, C.; Kazazian, C.; Raddatz, C.; Bacon, S.L. Impact of cognitive-behavioral interventions on weight loss and psychological outcomes: A meta-analysis. Health Psychol. 2018, 37, 417–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Psychiatric Association. The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed.; American Psychiatric Publishing: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Katterman, S.N.; Kleinman, B.M.; Hood, M.M.; Nackers, L.M.; Corsica, J.A. Mindfulness meditation as an intervention for binge eating, emotional eating, and weight loss: A systematic review. Eat. Behav. 2014, 15, 197–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raja-Khan, N.; Agito, K.; Shah, J.; Stetter, C.M.; Gustafson, T.S.; Socolow, H.; Kunselman, A.R.; Reibel, D.K.; Legro, R.S. Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction in Women with Overweight or Obesity: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Obesity 2017, 25, 1349–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fonseca, N.K.O.; Molle, R.D.; Costa, M.A.; Gonçalves, F.G.; Silva, A.C.; Rodrigues, Y.; Price, M.; Silveira, P.P.; Manfro, G.G. Impulsivity Influences Food Intake in Women with Generalized Anxiety Disorder. Braz. J. Psychiatry 2020, 42, 382–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teixeira, P.J.; Silva, M.N.; Coutinho, S.R.; Palmeira, A.L.; Mata, J.; Vieira, P.N.; Carraça, E.V.; Santos, T.C.; Sardinha, L.B. Mediators of Weight Loss and Weight Loss Maintenance in Middle-aged Women. Obesity 2010, 18, 725–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nurkkala, M.; Kaikkonen, K.; Vanhala, M.; Keränen, A.M.; Korpelainen, R.; Palaniswamy, S.; Savolainen, M.J.; Jokelainen, J.; Keinänen-Kiukaanniemi, S. Challenges in the maintenance of healthy lifestyle: A follow-up study. J. Prim. Care Community Health 2019, 10, 2150132719842268. [Google Scholar]

- Pigsborg, K.; Kalea, A.Z.; De Dominicis, S.; Magkos, F. Behavioral and Psychological Factors Affecting Weight Loss Success. Curr. Obes. Rep. 2023, 12, 223–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryant, E.J.; Rehman, J.; Pepper, L.B.; Walters, E.R. Obesity and Eating Disturbance: The Role of TFEQ Restraint and Disinhibition. Curr. Obes. Rep. 2019, 8, 363–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dakin, C.; Beaulieu, K.; Hopkins, M.; Gibbons, C.; Finlayson, G.; Stubbs, R.J. Do eating behavior traits predict energy intake and body mass index? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes. Rev. 2023, 24, e13515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wadden, T.A.; Neiberg, R.H.; Wing, R.R.; Clark, J.M.; Delahanty, L.M.; Hill, J.O.; Krakoff, J.; Otto, A.; Ryan, D.H.; Vitolins, M.Z.; et al. Four-year weight losses in the Look AHEAD study: Factors associated with long-term success. Obesity 2011, 19, 1987–1998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearl, R.L.; Puhl, R.M. Weight bias internalization and health: A systematic review. Obes. Rev. 2018, 19, 1141–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puhl, R.M.; Heuer, C.A. Obesity stigma: Important considerations for public health. Am. J. Public. Health 2010, 100, 1019–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarwer, D.B.; Polonsky, H.M. The Psychosocial Burden of Obesity. Endocrinol. Metab. Clin. North. Am. 2016, 45, 677–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puhl, R.; Suh, Y. Health Consequences of Weight Stigma: Implications for Obesity Prevention and Treatment. Curr. Obes. Rep. 2015, 4, 182–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friedman, K.E.; Reichmann, S.K.; Costanzo, P.R.; Zelli, A.; Ashmore, J.A.; Musante, G.J. Weight stigmatization and ideological beliefs: Relation to psychological functioning in obese adults. Obes. Res. 2005, 13, 907–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alghawrien, D.; Al-Hussami, M.; Ayaad, O. The impact of obesity on self-esteem and academic achievement among university students. Int. J. Adolesc. Med. Health 2020, 34, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puhl, R.M.; Brownell, K.D. Confronting and coping with weight stigma: An investigation of overweight and obese adults. Obesity 2006, 14, 1802–1815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pont, S.J.; Puhl, R.; Cook, S.R.; Slusser, W. Stigma experienced by children and adolescents with obesity. Pediatrics 2017, 140, e20173034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dessart, L.; Veloutsou, C.; Morgan-Thomas, A. Consumer engagement in online brand communities: A social media perspective. J. Prod. Brand. Manag. 2015, 24, 28–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollebeek, L. Exploring customer brand engagement: Definition and themes. J. Strateg. Mark. 2011, 19, 555–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennet, L.W.; Wells, C.; Freelon, P. Communicating Civic Engagement: Contrasting Models of Citizenship in the Youth Web Sphere. J. Commun. 2011, 61, 835–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordmo, M.; Danielsen, Y.S.; Nordmo, M. The challenge of keeping it off, a descriptive systematic review of high-quality, follow-up studies of obesity treatments. Obes. Rev. 2020, 21, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amâncio, M. Put It in Your Story: Digital Storytelling in Instagram and Snapchat Stories. Master’s Thesis, Uppsala University, Department of Informatics and Media, Media & Communication Studies, Uppsala, Sweden, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- YPULSE. Media Consumption Report. 2023. Available online: https://www.ypulse.com/report/2023/10/11/media-consumption-report-9/ (accessed on 23 July 2023).

- Wharton, S.; Lau, D.C.; Vallis, M.; Sharma, A.M.; Biertho, L.; Campbell-Scherer, D.; Adamo, K.; Alberga, A.; Bell, R.; Boulé, N.; et al. Obesity in adults: A clinical practice guideline. Can. Med. Assoc. J. 2020, 192, E875–E891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Number of Participants (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 18 to 30 | 14 (21.2) |

| 31 to 50 | 40 (60.6) | |

| ≥51 | 12 (18.2) | |

| Gender | Female | 63 (95.4) |

| Male | 3 (4.5) | |

| Education level (years) | ≤7 | 1 (3.0) |

| 8 to 10 | 3 (4.5) | |

| ≥11 | 62 (92.4) | |

| Diseases/Complications | Metabolic Diseases 1 | 38 (57.6) |

| Hormonal Issues 2 | 21 (31.8) | |

| Depression | 14 (21.2) | |

| Anxiety | 59 (89.4) | |

| Insomnia | 20 (30.3) | |

| Cancer | 3 (4.5) | |

| Respiratory Issues 3 | 12 (18.2) | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | Overweight (25 to 29.9 kg/m2) | 27 (40.9) |

| Obesity (30 to ≥ 40.0 kg/m2) | 39 (59.1) | |

| Parameters | Overweight (n = 27) | Obesity (n = 39) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Basal | 5 Weeks | p | d [IC95] | Basal | 5 Weeks | p | d [IC95] | |

| Body weight (kg) | 73.9 ± 7.8 | 72.8 ± 7.4 | 0.002 * | 0.601 [0.18–1.00] | 97.2 ± 15.9 † | 96.1 ± 15.2 | 0.010 * | 0.392 [0.06–0.71] |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 84.6 ± 7.8 | 83.5 ± 9.1 | 0.080 | 0.268 [−0.11–0.64] | 104.4 ± 10.8 † | 102.5 ± 10.9 | 0.147 | 0.171 [−0.14–0.48] |

| Binge eating | 16.5 ± 7.5 | 12.0 ± 6.0 | <0.001 * | 0.697 [0.27–1.11] | 24.4 ± 8.0 † | 18.5 ± 9.9 | <0.001 * | 0.656 [0.30–0.99] |

| Emotional eating | 14.2 ± 4.3 | 14.9 ± 3.9 | 0.180 | 0.179 [−0.55–0.20] | 15.4 ± 6.0 | 14.9 ± 4.7 | 0.246 | 0.111 [−0.20–0.42] |

| Cognitive restriction | 15.5 ± 1.9 | 15.8 ± 2.5 | 0.343 | 0.079 [−0.45–0.30] | 15.4 ± 3.0 | 15.5 ± 2.4 | 0.389 | 0.045 [−0.35–0.26] |

| Uncontrolled eating | 22.4 ± 4.9 | 21.8 ± 4.7 | 0.186 | 0.175 [−0.20–0.55] | 23.8 ± 4.3 | 22.1 ± 4.3 | 0.009 * | 0.398 [0.06–0.72] |

| Self-esteem | 30.1 ± 4.9 | 31.7 ± 4.8 | 0.101 | 0.252 [−0.63–0.13] | 27.8 ± 5.5 | 29.6 ± 4.8 | 0.027 * | 0.319 [−0.63–0.1] |

| Anxiety | 46.9 ± 9.2 | 45.7 ± 8.5 | 0.148 | 0.206 [−0.17–0.58] | 53.6 ± 7.8 † | 50.7 ± 7.6 | 0.001 * | 0.529 [0.19–0.86] |

| Perceived stress | 29.1 ± 4.9 | 23.5 ± 7.5 | <0.001 * | 0.698 [0.27–1.11] | 30.0 ± 7.7 | 27.7 ± 7.2 | 0.045 * | 0.279 [−0.43–0.59] |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Body weight | 1 | 0.318 | 0.047 | −0.280 | 0.101 | −0.143 | 0.005 | 0.122 | 0.046 | −0.191 | 0.041 |

| 2. Binge eating | 0.318 | 1 | −0.188 | −0.059 | −0.079 | −0.075 | 0.162 | 0.051 | −0.097 | −0.286 | 0.015 |

| 3. Emotional eating | 0.047 | −0.188 | 1 | −0.106 | 0.691 | −0.096 | 0.388 | 0.146 | 0.101 | 0.193 | 0.146 |

| 4. Cognitive restriction | −0.280 | −0.059 | −0.106 | 1 | −0.129 | −0.015 | −0.196 | −0.131 | 0.132 | 0.114 | −0.136 |

| 5. Uncontrolled eating | 0.101 | −0.079 | 0.691 | −0.129 | 1 | −0.032 | 0.329 | 0.258 | −0.083 | 0.067 | 0.081 |

| 6. Self-esteem | −0.143 | −0.075 | −0.096 | −0.015 | −0.032 | 1 | −0.096 | −0.241 | 0.063 | 0.187 | −0.046 |

| 7. Anxiety | 0.005 | 0.162 | 0.388 | −0.196 | 0.329 | −0.096 | 1 | 0.299 | 0.040 | 0.054 | −0.075 |

| 8. Perceived stress | 0.122 | 0.051 | 0.146 | −0.131 | 0.258 | −0.241 | 0.299 | 1 | 0.160 | −0.038 | 0.149 |

| 9. Engagement * | 0.046 | −0.097 | 0.101 | 0.132 | −0.083 | 0.063 | 0.040 | 0.160 | 1 | 0.350 | 0.586 |

| 10. Live sessions | −0.191 | −0.286 | 0.193 | 0.114 | 0.067 | 0.187 | 0.054 | −0.038 | 0.350 | 1 | 0.275 |

| 11. Direct messages | 0.041 | 0.015 | 0.146 | −0.136 | 0.081 | −0.046 | −0.075 | 0.149 | 0.586 | 0.275 | 1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rychescki, G.G.; dos Santos, G.R.; Bertin, C.F.; Pacheco, C.N.; Antunes, L.d.C.; Stanford, F.C.; Boaventura, B. Online Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy-Based Nutritional Intervention via Instagram for Overweight and Obesity. Nutrients 2024, 16, 4045. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16234045

Rychescki GG, dos Santos GR, Bertin CF, Pacheco CN, Antunes LdC, Stanford FC, Boaventura B. Online Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy-Based Nutritional Intervention via Instagram for Overweight and Obesity. Nutrients. 2024; 16(23):4045. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16234045

Chicago/Turabian StyleRychescki, Greta Gabriela, Gabriela Rocha dos Santos, Caroline Fedozzi Bertin, Clara Nogueira Pacheco, Luciana da Conceição Antunes, Fatima Cody Stanford, and Brunna Boaventura. 2024. "Online Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy-Based Nutritional Intervention via Instagram for Overweight and Obesity" Nutrients 16, no. 23: 4045. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16234045

APA StyleRychescki, G. G., dos Santos, G. R., Bertin, C. F., Pacheco, C. N., Antunes, L. d. C., Stanford, F. C., & Boaventura, B. (2024). Online Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy-Based Nutritional Intervention via Instagram for Overweight and Obesity. Nutrients, 16(23), 4045. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16234045