Comprehensive Management of Drunkorexia: A Scoping Review of Influencing Factors and Opportunities for Intervention

Highlights

- Drunkorexia is one of the newest alcohol-related behavioral disorders, and it must be detected and addressed from a multidisciplinary perspective.

- Drunkorexia is characterized by a low estimation of one’s weight and own appearance, inadequate eating patterns, excessive physical activity and an alcohol-related disorder.

- Modulating factors of drunkorexia involve difficulties in emotional regulation, symptoms of low self-esteem, distorted social expectations, or stressful and anxious symptomatology.

- Management directions should focus on the evaluation of comorbidities, favoring emotional regulation, promotion of healthy habits and eating routines, social education and community awareness.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Databases and Search Strategy

2.3. Eligibility Criteria

2.4. Risk of Bias Study and Methodological Assessment of Quality

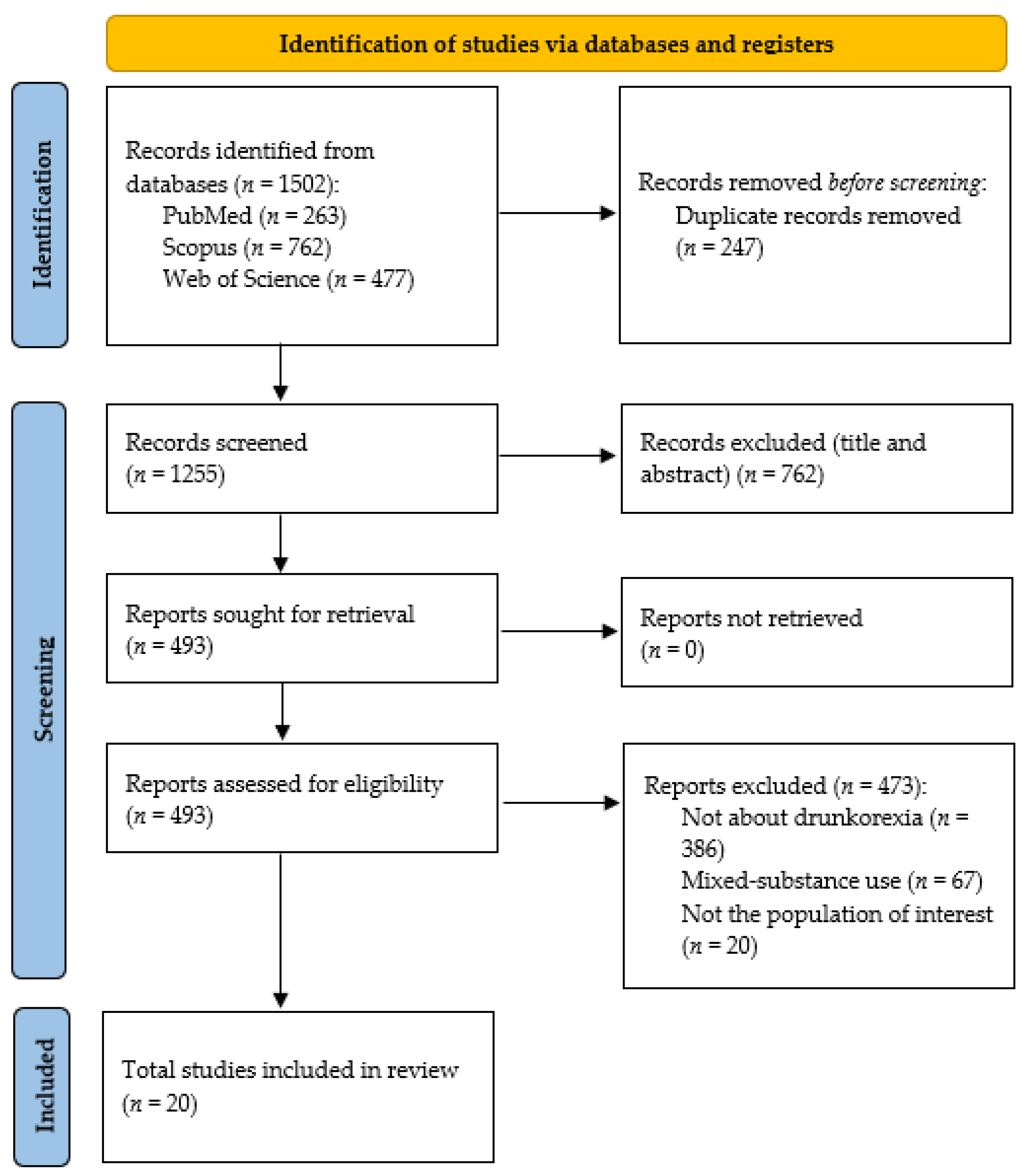

2.5. Study Flowchart

3. Results

3.1. Description of the Characteristics of the Selected Studies

3.2. Modulating Factors of Drunkorexia

3.3. Directions for the Management of Drunkorexia

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Thompson-Memmer, C.; Glassman, T.; Diehr, A. Drunkorexia: A new term and diagnostic criteria. J. Am. Coll. Health 2019, 67, 620–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piazza-Gardner, A.K.; Barry, A.E. Appropriate terminology for the alcohol, eating, and physical activity relationship. J. Am. Coll. Health 2013, 61, 311–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burke, S.C.; Cremeens, J.; Vail-Smith, K.; Woolsey, C. Drunkorexia: Calorie restriction prior to alcohol consumption among college freshman. J. Alcohol. Drug Educ. 2010, 54, 17–34. [Google Scholar]

- Roosen, K.M.; Mills, J.S. Exploring the motives and mental health correlates of intentional food restriction prior to alcohol use in university students. J. Health Psychol. 2015, 20, 875–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eisenberg, M.H.; Fitz, C.C. “Drunkorexia”: Exploring the who and why of a disturbing trend in college students’ eating and drinking behaviors. J. Am. Coll. Health 2014, 62, 570–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Tata, D.; Bianchi, D.; Pompili, S.; Laghi, F. The Psychological Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Alcohol Abuse and Drunkorexia Behaviors in Young Adults. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 3466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michael, M.L.; Witte, T.H. Traumatic stress and alcohol-related disordered eating in a college sample. J. Am. Coll. Health 2021, 69, 806–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szynal, K.; Szynal, K.; Górski, M.; Górski, M.; Grajek, M.; Grajek, M.; Ciechowska, K.; Ciechowska, K.; Polaniak, R.; Polaniak, R. Drunkorexia—Knowledge review. Psychiatr. Polska 2022, 56, 1131–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peralta, R.L.; Schnellinger, R.P.; Wade, J.M.; Barr, P.B.; Carter, J.R. The association between Food and Alcohol Disturbance (FAD), race, and ethnic identity belonging. Eat. Weight. Disord. 2019, 24, 705–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malaeb, D.; Bianchi, D.; Pompili, S.; Berro, J.; Laghi, F.; Azzi, V.; Akel, M.; Obeid, S.; Hallit, S. Drunkorexia behaviors and motives, eating attitudes and mental health in Lebanese alcohol drinkers: A path analysis model. Eat. Weight. Disord. 2022, 27, 1787–1797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell-Jones, A.; Simpson, S. Drunkorexia: An investigation of symptomatology and early maladaptive schemas within a female, young adult Australian population. Aust. Psychol. 2020, 55, 559–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-5 (Volume 5); American Psychiatric Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Kurata, T.; Hashimoto, T.; Suzuki, H.; Ishige, M.; Kikuchi, S. Effect of a multidisciplinary approach on hospital visit continuation in the treatment of patients with alcohol dependence. Neuropsychopharmacol. Rep. 2023, 43, 542–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moriarty, K.J. Collaborative liver and psychiatry care in the Royal Bolton Hospital for people with alcohol-related disease. Front. Gastroenterol. 2011, 2, 77–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gitto, S.; Golfieri, L.; Caputo, F.; Grandi, S.; Andreone, P. Multidisciplinary View of Alcohol Use Disorder: From a Psychiatric Illness to a Major Liver Disease. Biomolecules 2016, 6, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ávila, P.; Marcos, M.; Ávila, J.; Laso, F. Influencia de la derivación a un Servicio de Medicina Interna en el seguimiento de pacientes alcohólicos [Referral to internal medicine for alcoholism: Influence on follow-up care]. Rev. Clin. Espanola 2008, 208, 499–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, B. Understanding Eating Disorders and the Nurse’s Role in Diagnosis, Treatment, and Support. J. Christ. Nurs. 2024, 41, 80–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Federación Nacional de Enfermos y Trasplantados Hepáticos (FNETH). Buenas Prácticas Enfermeras: Detección Precoz de Consumo de Alcohol; Delegación del Gobierno para el Plan Nacional sobre Drogas: Madrid, España, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Dionisi, T.; Mosoni, C.; Di Sario, G.; Tarli, C.; Antonelli, M.; Sestito, L.; D’addio, S.; Tosoni, A.; Ferrarese, D.; Iasilli, G.; et al. Make Mission Impossible Feasible: The Experience of a Multidisciplinary Team Providing Treatment for Alcohol Use Disorder to Homeless Individuals. Alcohol Alcohol. 2020, 55, 547–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peters, M.D.J.; Godfrey, C.M.; Khalil, H.; McInerney, P.; Parker, D.; Soares, C.B. Guidance for conducting systematic scoping reviews. JBI Evid. Implement. 2015, 13, 141–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollock, D.; Peters, M.D.; Khalil, H.; McInerney, P.; Alexander, L.; Tricco, A.C.; Evans, C.; de Moraes, B.; Godfrey, C.M.; Pieper, D.; et al. Recommendations for the extraction, analysis, and presentation of results in scoping reviews. JBI Evid. Synth. 2023, 21, 520–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aromataris, E.; Lockwood, C.; Porritt, K.; Pilla, B.; Jordan, Z. (Eds.) JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis; JBI: Adelaide, Australia, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.; McKenzie, J.; Bossuyt, P.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.; Mulrow, C.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.; Akl, E.; Brennan, S.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azzi, V.; Hallit, S.; Malaeb, D.; Obeid, S.; Brytek-Matera, A. Drunkorexia and emotion regulation and emotion regulation difficulties: The mediating effect of disordered eating attitudes. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pompili, S.; Laghi, F. Drunkorexia among adolescents: The role of motivations and emotion regulation. Eat. Behav. 2018, 29, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laghi, F.; Pompili, S.; Bianchi, D.; Lonigro, A.; Baiocco, R. Dysfunctional metacognition processes as risk factors for drunkorexia during adolescence. J. Addict. Dis. 2020, 38, 291–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laghi, F.; Pompili, S.; Bianchi, D.; Lonigro, A.; Baiocco, R. Psychological characteristics and eating attitudes in adolescents with drunkorexia behavior: An exploratory study. Eat. Weight. Disord. 2020, 25, 709–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laghi, F.; Pompili, S.; Bianchi, D.; Lonigro, A.; Baiocco, R. Drunkorexia: An Examination of the Role of Theory of Mind and Emotional Awareness among Adolescents. Dev. Neuropsychol. 2021, 46, 70–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laghi, F.; Pompili, S.; Bianchi, D.; Lonigro, A.; Baiocco, R. Exploring the association between psychological distress and drunkorexia behaviors in non-clinical adolescents: The moderating role of emotional dysregulation. Eat. Weight. Disord. 2021, 26, 797–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oswald, B.B.; Ward, R.M.; Glazer, S.; Sternasty, K.; Day, K.; Speed, S. Baseline cortisol predicts drunkorexia in female but not male college students. J. Am. Coll. Health 2021, 69, 625–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogt, K.S.; Harper, M.; Griffin, B.L. “… because I’m so drunk at the time, the last thing I’m going to think about is calories”: Strengthening the argument for Drunkorexia as a food and alcohol disturbance, evidence from a qualitative study. Br. J. Health Psychol. 2022, 27, 1188–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffin, B.L.; Vogt, K.S. Drunkorexia: Is it really “just” a university lifestyle choice? Eat. Weight. Disord. 2021, 26, 2021–2031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, E.M.; Lego, J.E. Examining the role of body esteem and sensation seeking in drunkorexia behaviors. Eat. Weight. Disord. 2020, 25, 1507–1513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lupi, M.; Martinotti, G.; Di Giannantonio, M. Drunkorexia: An emerging trend in young adults. Eat. Weight. Disord. 2017, 22, 619–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gorrell, S.; Walker, D.C.; Anderson, D.A.; Boswell, J.F. Gender differences in relations between alcohol-related compensatory behavior and eating pathology. Eat. Weight. Disord. 2018, 24, 715–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ward, R.M.; Galante, M. Development and initial validation of the Drunkorexia Motives and Behaviors scales. Eat. Behav. 2015, 18, 66–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choquette, E.M.; Dedrick, R.; Thompson, J.K.; Rancourt, D. Reexamination of the psychometric properties of the Compensatory Eating and Behaviors in Response to Alcohol Consumption Scale (CEBRACS) and exploration of alternative scoring. Eat. Behav. 2020, 38, 101410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritz, L.; Mauny, N.; Leconte, P.; Margas, N. French validation of the Compensatory Eating and Behaviors in Response to Alcohol Consumption Scale (CEBRACS) in a university student sample. Eat. Weight. Disord. 2023, 28, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López-Moreno, M.; Garcés-Rimón, M.; Miguel, M.; López, M.T.I. Adherence to Mediterranean Diet, Alcohol Consumption and Emotional Eating in Spanish University Students. Nutrients 2021, 13, 3174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glassman, T.; Paprzycki, P.; Castor, T.; Wotring, A.; Wagner-Greene, V.; Ritzman, M.; Diehr, A.J.; Kruger, J. Using the Elaboration Likelihood Model to Address Drunkorexia among College Students. Subst. Use Misuse 2018, 53, 1411–1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romano, K.A.; Stamates, A.; Heron, K.E.; Braitman, A.L.; Lau-Barraco, C. Sex and Racial Differences in Patterns of Disordered Eating and Alcohol Use. Behav. Med. 2020, 47, 272–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horvath, S.A.; Shorey, R.C.; Racine, S.E. Emotion dysregulation as a correlate of food and alcohol disturbance in undergraduate students. Eat. Behav. 2020, 38, 101409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswal, B.; Bora, S.; Anand, R.; Bhatia, U.; Fernandes, A.; Joshi, M.; Nadkarni, A. A systematic review of interventions to enhance initiation of and adherence to treatment for alcohol use disorders. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2024, 263, 112429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallihan, H.; Srimoragot, M.; Ma, J.; Hanneke, R.; Lee, S.; Rospenda, K.; Fink, A.M. Integrated behavioral interventions for adults with alcohol use disorder: A systematic review. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2024, 263, 111406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knopp, M.; Burghardt, J.; Oppenauer, C.; Meyer, B.; Moritz, S.; Sprung, M. Affective and cognitive Theory of Mind in patients with alcohol use disorder: Associations with symptoms of depression, anxiety, and somatization. J. Subst. Use Addict. Treat. 2024, 157, 209227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Volpe, S.L. Alcohol and Athletic Performance. ACSM’S Health Fit. J. 2010, 14, 28–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiss, D.A.; Schellenberger, M.; Prelip, M.L. Registered Dietitian Nutritionists in Substance Use Disorder Treatment Centers. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2018, 118, 2217–2221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osorio, O.; Amaya, M.C.d.P. Panorama de prácticas de alimentación de adolescentes escolarizados. Av. en Enfermería 2009, 27, 43–56. [Google Scholar]

- Amezcua, M.; García Pedregal, E.; Jordana, J.; Llisterri, J.L.; Rodríguez Sampedro, A.; Villarino Marín, A. La educación ante el consumo de riesgo de bebidas alcohólicas: Propuesta de actuación multidisciplinar desde el profesional de la salud. [Education facing risk consumption of alcoholic beverages—A proposal for multidisciplinary action from the health care professionals]. Nutr. Hosp. 2020, 37, 609–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groth, G.G.; Longo, L.M.; Martin, J.L. Social media and college student risk behaviors: A mini-review. Addict. Behav. 2017, 65, 87–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, Y.; Kozachik, S.L.; Hansen, B.R.; Sanchez, M.; Finnell, D.S. Nurse-Led Delivery of Brief Interventions for At-Risk Alcohol Use: An Integrative Review. J. Am. Psychiatr. Nurses Assoc. 2020, 26, 27–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barilati, E.M.; Cantoni, B.; Bezze, E. Abuso Alcolico Negli Adolescenti. Analisi di un Problema Trascurato [Alcohol Abuse in Teenagers. Analysis of a Neglected Problem]. Child. Nurses: Ital. J. Pediatr. Nurs. Sci./Inferm. Dei Bambini: G. Ital. Di Sci. Inferm. Pediatr. 2014, 6, 53–57. [Google Scholar]

- Cochran, G.; Field, C. Brief Intervention and Social Work: A Primer for Practice and Policy. Soc. Work Public Health 2013, 28, 248–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brady, K.T.; Haynes, L.F.; Hartwell, K.J.; Killeen, T.K. Substance use disorders and anxiety: A treatment challenge for social workers. Soc. Work Public Health 2013, 28, 407–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warpenius, K.; Mäkelä, P. The Finnish Drinking Habits Survey: Implications for alcohol policy and prevention. Nord. Stud. Alcohol Drugs 2020, 37, 619–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Picoito, J.; Santos, C. Desafios na adopção de medidas públicas para a redução do consumo de álcool em jovens. Psilogos 2019, 17, 55–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chambers, R.A. Drunkorexia. J. Dual Diagn. 2008, 4, 414–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| P (Population) | Adolescents and young people. |

| C (Concept) | Factors influencing drunkorexia. |

| C (Context) | Multidisciplinary detection and interventions. |

| Database | Search Strategy | Filters | Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| PubMed | (“alcohol drinking” OR “alcohol drinking habits” OR “alcohol consumption” OR “alcohol intake” OR “binge drinking” OR “drunkorexia”) AND (“feeding and eating disorders” OR “eating disorders” OR “feeding disorders”) | Publication date: from January 2008 to July 2024. | 263 |

| Scopus | (“alcohol drinking” OR “alcohol drinking habits” OR “alcohol consumption” OR “alcohol intake” OR “binge drinking” OR “drunkorexia”) AND (“feeding and eating disorders” OR “eating disorders” OR “feeding disorders”) | Publication date: from January 2008 to July 2024. Limited to articles. | 762 |

| Web of Science | (“alcohol drinking” OR “alcohol drinking habits” OR “alcohol consumption” OR “alcohol intake” OR “binge drinking” OR “drunkorexia”) AND (“feeding and eating disorders” OR “eating disorders” OR “feeding disorders”) | Publication date: from January 2008 to July 2024. Limited to articles. | 477 |

| Author(s), Year, Country | Objective | Study Design and Sample | Main Results and Conclusions | JBI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Azzi et al., 2021) [24] Lebanon | To investigate the association of drunkorexia with emotion regulation as well as emotion regulation difficulties across the Lebanese population and to assess disordered eating attitudes as potential mediators of these relationships. | Cross-sectional. A total of 258 (75.88%) out of 340 participants (21.3% women) from all Lebanese districts participated in this study (mean age = 26.96; SD = 9.39 years). | This study highlighted that only emotional regulation difficulties were associated with drunkorexia, whereas emotional regulation was not significantly associated with such behavior. Additionally, drunkorexia patterns were only partially mediated by disordered eating attitudes. | 7/8 |

| (Choquette et al., 2020) [37] USA | To reexamine the factor structure of the 21-item CEBRACS, a measure of FAD, and investigate an alternative scoring structure. | Cross-sectional. Participants were 586 young adults (77.6% women) from 18 to 30 years old (mean age = 20.98; SD = 2.31 years). | The CEBRACS is the only measure that assesses FAD behaviors by both time and motive. Retaining the original four-factor structure allows for a holistic view of behaviors, although some caution is necessary when interpreting the Restriction subscale. The new time-based scoring method demonstrated promising psychometrics and allowed for the examination of FAD by time of engagement and motive. | 8/8 |

| (Glassman et al., 2018) [40] USA | To use the Elaboration Likelihood Model to compare the impact of central and peripheral prevention messages on alcohol consumption and drunkorexic behavior. | Quasi-experimental. 172 college students (66% women) living in residence halls at a large Midwestern university from 18 to 24 years old (mean age = 19.2; SD = 1.01 years). | Through the use of the elaboration probability model to identify the impact of central and peripheral prevention messages that addressed alcohol consumption and the trend of drunkorexia, participants exposed to the peripherally framed message decreased the frequency of their alcohol consumption over a 30-day period, the number of drinks they consumed the last time they drank, the frequency with which they had more than five drinks over a 30-day period, as well as the maximum number of drinks they had on any occasion in the past 30 days. | 8/9 |

| (Gorrell et al., 2019) [35] USA | To assess how specific types of alcohol-related compensatory behaviors and their association with ED pathology present differently by gender. | Cross-sectional. A sample of 530 undergraduate Psychology research pool students (48% women) at a large Northeastern university (mean age of men = 18.96, SD = 1.75 years; mean age of women = 19.48, SD = 1.56 years). | The findings indicated that specific types of alcohol-related compensatory eating behaviors (i.e., dietary restraint and exercise) are positively related to ED pathology for both male and female participants. In contrast, bulimic behaviors’ association with ED pathology is gender-specific. Understanding gender differences in alcohol-related compensatory behaviors and ED risk may inform gender-specific intervention targets. | 8/8 |

| (Griffin and Vogt, 2021) [32] United Kingdom | To investigate the prevalence of compensatory behaviors (caloric restriction, increased exercise, and bulimic tendencies) in response to alcohol consumption (also known as drunkorexia) in students, non-students, and previous students, as well as to understand the presence of possible predictors of these behaviors (body esteem and sensation seeking). | Cross-sectional. A sample of 95 students, non-students, and previous students (77.9% women), from 18 to 26 years old (mean age = 21.39; SD = 2.46 years). | Findings suggested that drunkorexia is also present outside of student populations; therefore, future interventions and research should include non-students in samples. Both low body esteem and high-sensation-seeking tendencies were significant predictors of drunkorexia, specifically, the appearance of esteem and disinhibition factors. The findings support the idea that drunkorexia cannot be classified solely as an eating disorder or as a substance abuse disorder. | 6/8 |

| (Hill and Lego, 2020) [33] USA | To examine the role of SS and BE (which comprises WE and AE), and their interaction in drunkorexia. | Cross-sectional. A sample of 488 college students (69.5% women) from 18 to 36 years old (mean age = 19.16; SD = 1.80 years). | Results indicated that SS and BE did not interact in predicting drunkorexia. Rather, only main effects were observed: SS, WE, and AE were significant in predicting overall drunkorexia engagement. In terms of the drunkorexia dimensions, AE was a significant predictor in the alcohol effects, dietary restraint and exercise, and restriction models. WE was significant in the dietary restraint and exercise model, as well as in the restriction model. SS was a significant predictor across all drunkorexia dimensions. | 7/8 |

| (Laghi et al., 2020a) [26] Italy | To investigate the relation between drunkorexia and psychological characteristics relevant to and commonly associated with existing forms of eating disorders. | Cross-sectional. The sample was composed of 849 adolescents (39.3% women) from 14 to 22 years old (mean age = 17.89; SD = 1.10 years). | Findings highlighted that drunkorexia was associated with low self-esteem, personal alienation, interoceptive deficits, emotional dysregulation, and asceticism. Hierarchical multiple regression analysis indicated that difficulties with emotion regulation and ascetic tendencies were significant predictors of drunkorexia among adolescents. Therefore, it is suggested that, importantly, programs aimed at preventing drunkorexia focus on training adolescents to use more adaptive strategies for managing emotions and to accept both emotional and physical signals without feeling guilt or threat. | 7/8 |

| (Laghi et al., 2020b) [27] Italy | To investigate the potential role of metacognitive processes in drunkorexia in a sample of adolescents. | Cross-sectional. A total sample of 719 adolescents (49.1% women) from 15 to 20 years old (mean age = 17.43; SD = 1.00 years). | Results showed that drunkorexia was associated with dysfunctional metacognitive processes; specifically, the metacognitive beliefs regarding the need to control thoughts, the negative beliefs about the uncontrollability and danger of worrying, and the positive metacognitions about alcohol use were significant predictors of drunkorexia. The findings suggest the relevance of prevention efforts to train adolescents to develop alternative self-regulation strategies and more adaptive ways of monitoring thoughts. | 7/8 |

| (Laghi et al., 2021a) [28] Italy | To investigate ToM and emotional awareness in drunkorexia, an emerging behavior characterized by calorie restriction when drinking alcohol is planned. | Cross-sectional. A sample of 246 adolescents (60.1% women) from 17 to 20 years old (mean age = 18.12; SD = 0.48 years). | Drunkorexia was negatively correlated with ToM abilities, with reading neutral emotions, and positively correlated with lack of emotional awareness. ToM and lack of emotional awareness were also found to predict drunkorexia. Findings highlighted that those adolescents who engage in drunkorexia may have difficulties in reading others’ mental states and being aware of their emotions. | 8/8 |

| (Laghi et al., 2021b) [29] Italy | To investigate the relation between symptoms of anxiety and depression and drunkorexia and to explore the role of emotional dysregulation as moderator of this relationship. | Cross-sectional. The sample was composed of 402 adolescents (55.2% women) from 15 to 21 years old (mean age = 18.10; SD = 0.88 years). | Anxious symptomatology resulted in a significant statistical predictor of drunkorexia behaviors. Furthermore, emotional dysregulation moderated the relation between anxiety and drunkorexia; specifically, a positive relation was found at both medium and higher levels of emotional dysregulation, whereas at lower levels of emotional dysregulation, this association became nonsignificant. | 8/8 |

| (López-Moreno et al., 2021) [39] Spain | To detect early-risk alcohol consumption and alcohol dependence, the degree of adherence to the Mediterranean diet and emotional eating in university students of the Madrid community. | Cross-sectional. The studied sample was 584 students (71.9% women) from different degree programs in health sciences: medicine, pharmacy, biotechnology, nursing, physiotherapy, psychology, and gastronomy (mean age = 21.2; SD = 4 years). | Findings showed a large proportion of students with low adherence to the Mediterranean diet, as well as a high proportion of students with high-risk alcohol consumption and eating in response to emotions. Future co-design work to design invention strategies focusing on eating behaviors and alcohol use in young adults must be developed. Furthermore, to avoid serious unhealthy consequences, the implementation of actions to correct deviations related to alcohol abuse and negative relationships with food are necessary. | 7/8 |

| (Lupi et al., 2017) [34] Italy | To capture specific eating and drinking habits that may provide information on the prevalence of drunkorexia among Italian young adults, as well as the possible relationship between drunkorexic attitudes and the use of drugs of abuse. | Cross-sectional. A sample of 4275 healthy subjects (56.1% women), from 18 to 26 years old (mean age = 22.04; SD = 2.52 years). | Data identified drunkorexia as a common behavior among Italian young adults. Raising awareness on drunkorexia may help healthcare providers to timely address and approach its possible short- and long-term consequences. In addition, a significant correlation was found between drunkorexic attitudes and, respectively, binge drinking behaviors, use of cocaine, and use of novel psychoactive substances. | 7/8 |

| (Malaeb et al., 2022) [10] Lebanon | To investigate an association between depression, anxiety, and stress and drunkorexia behaviors/motives among Lebanese adults, while evaluating the mediating role of inappropriate eating attitudes in these associations. | Cross-sectional. A total of 258 participants (21.3% women) from 18 to 80 years old took part in the survey (mean age = 26.96; SD = 9.39 years). | Findings highlighted that those individuals with more psychological problems (depression, anxiety, and stress) and inappropriate eating habits exhibit more drunkorexic motivations and behaviors. | 7/8 |

| (Michael and Witte, 2021) [7] USA | To examine the association between posttraumatic stress symptoms and disordered eating behaviors related to alcohol consumption (i.e., “drunkorexia”). | Cross-sectional. Participants were 478 undergraduate students (74.9% women) at a university in the southeastern United States (mean age = 18.96; SD = 1.11 years). | Findings confirmed previous research that symptoms of eating disorders and symptoms of problem drinking predict disordered eating patterns surrounding alcohol use and further indicate that trauma may play an important role in such behaviors. Results have implications for trauma-informed treatment for college students presenting with “drunkorexia”. | 6/8 |

| (Oswald et al., 2021) [30] USA | To examine cortisol function as it relates to drunkorexia. | Cross-sectional. A sample of 73 undergraduate college students (67.1% women) from of all academic years enrolled in a mid-sized, Midwestern university (mean age = 19.1; SD = 1.3 years). | Results indicated that baseline cortisol was significantly positively correlated with drunkorexia behaviors in women but not in men. Higher baseline cortisol and aspects of drunkorexia related to alcohol problems. Furthermore, programs educating about stress management and health risks of drunkorexia may decrease engagement in drunkorexia behaviors among college students. | 8/8 |

| (Pompili and Laghi, 2018) [25] Italy | To examine the association of drunkorexia with various disordered eating behaviors and alcohol consumption in a sample of male and female adolescents. In addition, to investigate the motivations underlying drunkorexia and to examine the relationship between drunkorexia and different dimensions of emotion regulation. | Cross-sectional. A sample of 1000 adolescents (60.8% women) from 16 to 21 years old (mean age = 17.86; SD = 0.83 years). | Results revealed that fasting and engaging in binge drinking and becoming intoxicated were significant predictors of drunkorexia in both males and females; furthermore, females were found to engage in drunkorexia mainly for enhancement motives. Conversely, drunkorexia in males was significantly predicted by difficulties regulating emotions. | 7/8 |

| (Ritz et al., 2023) [38] France | To validate a French version of the CEBRACS in a representative sample of university students and to determine its validity and reliability. | Cross-sectional. 1112 students (65.4% women) from 18 to 36 years old (mean age = 20.3; SD = 2.59 years) at the University of Caen, Normandy (France), made up the final sample. | Findings highlighted the reliability and validity of the French version of the CEBRACS. The distinct factors identified in the CEBRACS allow for distinguishing between participants with different motives for engaging in FAD behavior and thus for preventing future development of eating and/or alcohol use disorders. The CEBRACS seems to be a relevant scale to capture FAD behaviors and thus to prevent negative and deleterious consequences | 8/8 |

| (Romano et al., 2021) [41] USA | To determine how young adults’ use of DEBs and alcohol uniquely clusters, how these clusters differ by sex and race, and map onto health-related correlates. | Cross-sectional. The sample includes 1371 individuals (74.9% women) aged from 18 to 25 years (mean age = 20.54; SD = 1.80 years). | Qualitative and quantitative differences were identified in the best-fitting mixture models for female (four groups), male (four groups), White (five groups), and Black (three groups) participants that suggest sex and racial variations exist in patterns of DEBs and alcohol use severity. Generally, classification into groups characterized by moderate to high probabilities of DEBs only, or by the combination of moderate to high DEBs and alcohol use, was associated with worse affective concerns across sexes and races. Targeting young adults’ DEBs and alcohol use via diversity-informed treatments focused on coping skill development may help promote health and well-being. | 7/8 |

| (Vogt et al., 2022) [31] United Kingdom | To extend knowledge on drunkorexia through to qualitatively explore the reasons and motivations for compensatory behaviors in response to alcohol consumption (restricting calorie intake, purging, and excessive exercise), specifically before, during, and after alcohol consumption. | Qualitative. Qualitative interviews with 10 participants (8/10 women) from 20 to 25 years old (mean age = 23.2 years). | Results showed that drunkorexia is driven by appearance-related concerns, such as wanting to look better/slimmer, engaging in behaviors related to an event, such as going out drinking, and continuing these behaviors despite negative health-related consequences. However, disregard for compensatory behaviors once drunk was also described, culminating in the consumption of high-calorie food. This suggested that drunkorexia is not a persistent pattern of maladaptive behavior, as found in eating or substance use disorders. Wanting value for money (i.e., feeling the maximum intoxication) was described as another reason for drunkorexia engagement, thus indicating that participants consider compensatory behaviors a routine part of going out drinking. | 10/10 |

| (Ward and Galante, 2015) [36] USA | To develop a measure of motivations for drunkorexia before, during, and after alcohol consumption. | Cross-sectional. The participants were college students (72.8% women) who ranged from 18 to 58 years old (mean age = 20.71; SD = 3.79 years). | Findings illustrated drunkorexia as a phenomenon apart from alcohol consumption or disordered eating behaviors alone. Drunkorexia motives seem to be derived from conformity drinking motives. Male students report higher levels of drunkorexia motives and consuming alcohol when drunkorexia fails. The newly developed measures provide an additional perspective on the drunkorexia literature. | 7/8 |

| Modulating Factors | Management Directions | Health Professionals |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pérez-Ortiz, N.; Andrade-Gómez, E.; Fagundo-Rivera, J.; Fernández-León, P. Comprehensive Management of Drunkorexia: A Scoping Review of Influencing Factors and Opportunities for Intervention. Nutrients 2024, 16, 3894. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16223894

Pérez-Ortiz N, Andrade-Gómez E, Fagundo-Rivera J, Fernández-León P. Comprehensive Management of Drunkorexia: A Scoping Review of Influencing Factors and Opportunities for Intervention. Nutrients. 2024; 16(22):3894. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16223894

Chicago/Turabian StylePérez-Ortiz, Naroa, Elena Andrade-Gómez, Javier Fagundo-Rivera, and Pablo Fernández-León. 2024. "Comprehensive Management of Drunkorexia: A Scoping Review of Influencing Factors and Opportunities for Intervention" Nutrients 16, no. 22: 3894. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16223894

APA StylePérez-Ortiz, N., Andrade-Gómez, E., Fagundo-Rivera, J., & Fernández-León, P. (2024). Comprehensive Management of Drunkorexia: A Scoping Review of Influencing Factors and Opportunities for Intervention. Nutrients, 16(22), 3894. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16223894