The Consumption of Non-Sugar Sweetened and Ready-to-Drink Beverages as Emerging Types of Beverages in Shanghai

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Method

2.1. Participants

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Covariates and Categorization

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Basic Information of the Survey Population

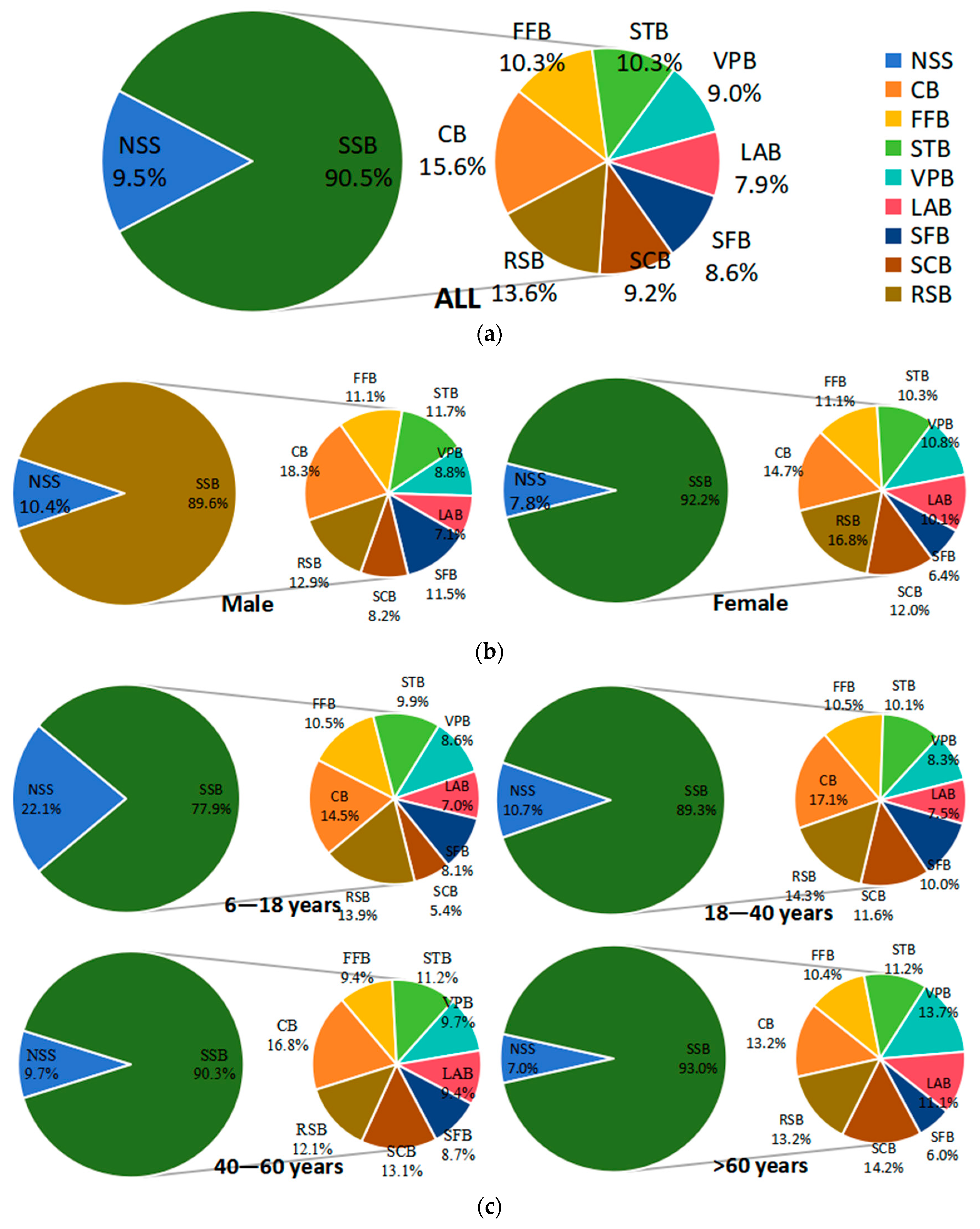

3.2. Consumption Rate and Consumption Amount of Different Types of Beverages

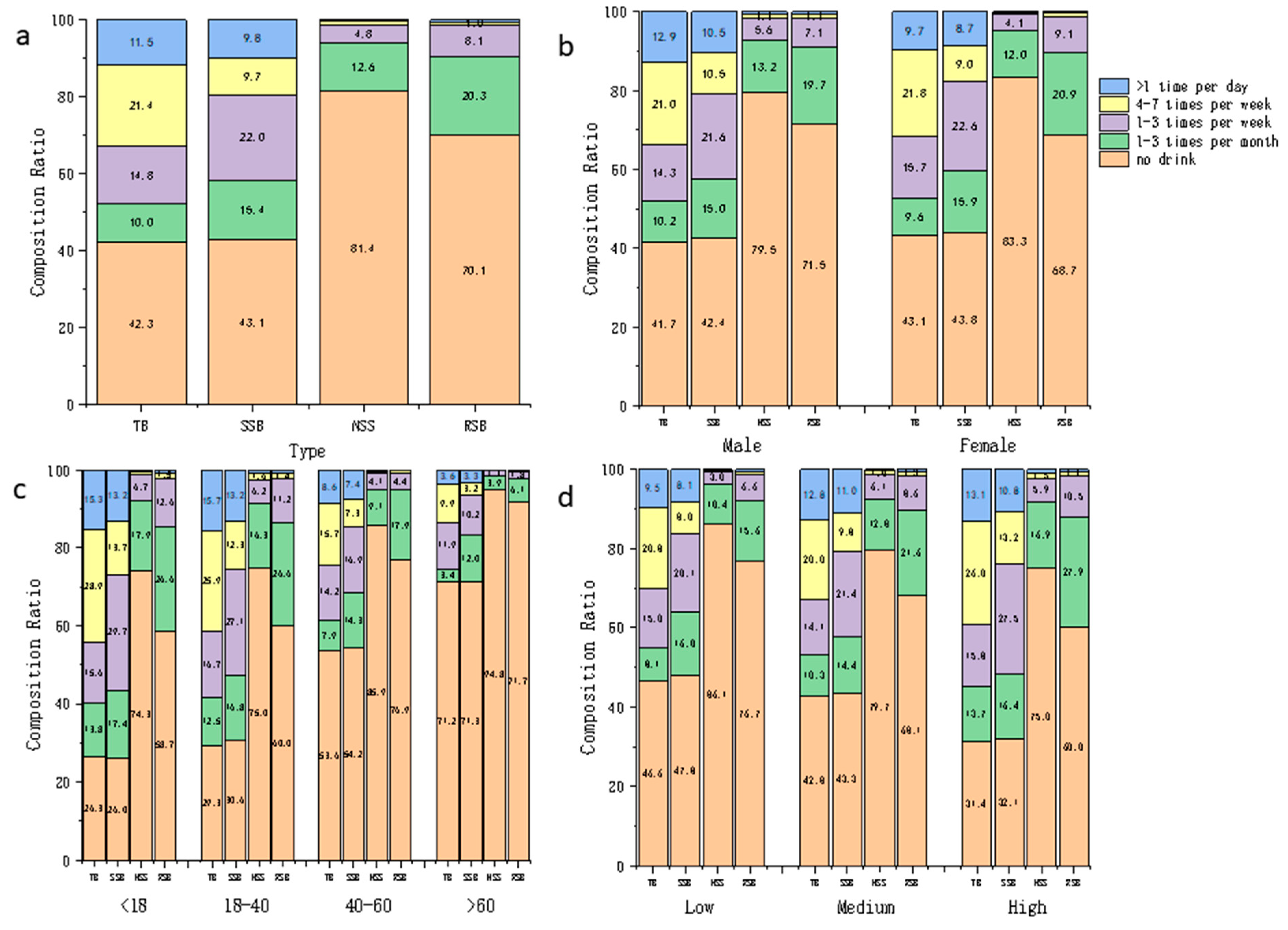

3.3. Consumption Amount and Frequency Distribution of Beverages

3.4. The Multifactorial Analyses Result of Influencing Factors Related to the Consumption of Beverages

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- National Bureau of Statistics of China. [EB/OL]. (2023-12-31). Available online: https://www.stats.gov.cn/ (accessed on 8 April 2024).

- Lara-Castor, L.; Micha, R.; Cudhea, F.; Miller, V.; Shi, P.; Zhang, J.; Sharib, J.R.; Erndt-Marino, J.; Cash, S.B.; Mozaffarian, D. Sugar-sweetened beverage intakes among adults between 1990 and 2018 in 185 countries. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 5957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, N.; Morin, C.; Guelinckx, I.; Moreno, L.A.; Kavouras, S.A.; Gandy, J.; Martinez, H.; Salas-Salvadó, J.; Ma, G. Fluid intake in urban China: Results of the 2016 Liq.In (7) national cross-sectional surveys. Eur. J. Nutr. 2018, 57 (Suppl. S3), 77–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Y.; Chen, Z.; Chen, B.; Li, J.; Yuan, X.; Li, J.; Wang, W.; Dai, T.; Chen, H.; Wang, Y.; et al. Dietary sugar consumption and health: Umbrella review. BMJ 2023, 381, e071609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, V.S.; Pan, A.; Willett, W.C.; Hu, F.B. Sugar-sweetened beverages and weight gain in children and adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2013, 98, 1084–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, V.S.; Hu, F.B. The role of sugar-sweetened beverages in the global epidemics of obesity and chronic diseases. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2022, 18, 205–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, G.M.; Micha, R.; Khatibzadeh, S.; Lim, S.; Ezzati, M.; Mozaffarian, D. Estimated Global, Regional, and National Disease Burdens Related to Sugar-Sweetened Beverage Consumption in 2010. Circulation 2015, 132, 639–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, V.S.; Li, Y.; Pan, A.; De Koning, L.; Schernhammer, E.; Willett, W.C.; Hu, F.B. Long-Term Consumption of Sugar-Sweetened and Artificially Sweetened Beverages and Risk of Mortality in US Adults. Circulation 2019, 139, 2113–2125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Report Hall. Milk Tea Market Analysis 2023: Asia Is the Major Consuming Region of Milk Tea Market [EB/OL]. (2023-10-13). Available online: https://www.chinabgao.com/freereport/90251.html (accessed on 5 March 2024).

- TIMON. China’s Sugar-Free Beverage Industry Research Report in 2022 [EB/OL]. (2022-05-26). Available online: https://data.eastmoney.com/report/zw_industry.jshtml?infocode=AP202205261568020049 (accessed on 25 April 2024).

- World Health Organization. Use of Non-Sugar Sweeteners: WHO Guideline [R]. (2023.5.15). Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240073616 (accessed on 25 April 2024).

- National Health Commission of the People’s Republic of China. Criteria of Weight for Adults [R/OL]. (2013-04-18). Available online: http://www.nhc.gov.cn/zwgkzt/yingyang/201308/a233d450fdbc47c5ad4f08b7e394d1e8.shtml (accessed on 8 April 2024).

- National Health Commission of the People’s Republic of China. Screening for Overweight and Obesity Among School-Age Children and Adolescents [R/OL]. (2018-02-23). Available online: http://www.nhc.gov.cn/fzs/s7852d/201803/7595325d43bb4417945edd570b1b12fa.shtml (accessed on 8 April 2024).

- National Health Commission of the People’s Republic of China. Growth Standard for Children Under 7 Years of Age [R/OL]. (2022-09-19). Available online: http://www.nhc.gov.cn/wjw/fyjk/202211/16d8b049fdf547978a910911c19bf389.shtml (accessed on 8 April 2024).

- Hill, C.M.; Chi, D.L.; Mancl, L.A.; Jones-Smith, J.C.; Chan, N.; Saelens, B.E.; McKinney, C.M. Sugar-sweetened beverage intake and convenience store shopping as mediators of the food insecurity—Tooth decay relationship among low-income children in Washington state. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0290287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laniado, N.; Sanders, A.E.; Godfrey, E.M.; Salazar, C.R.; Badner, V.M. Sugar-sweetened beverage consumption and caries experience: An examination of children and adults in the United States, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2011–2014. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 2020, 151, 782–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, J.; Soto, M.J.; Dunn, C.G.; Bleich, S.N. Trends and patterns in sugar-sweetened beverage consumption among children and adults by race and/or ethnicity, 2003–2018. Public Health Nutr. 2021, 24, 2405–2410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, C.; Ettridge, K.; Wakefield, M.; Pettigrew, S.; Coveney, J.; Roder, D.; Durkin, S.; Wittert, G.; Martin, J.; Dono, J. Consumption of Sugar-Sweetened Beverages, Juice, Artificially-Sweetened Soda and Bottled Water: An Australian Population Study. Nutrients 2020, 12, 817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kleiman, S.; Ng, S.W.; Popkin, B. Drinking to our health: Can beverage companies cut calories while maintaining profits? Obes. Rev. 2012, 13, 258–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, F.; Luan, D.C.; Zhang, T.W.; Mao, W.F.; Liang, D.; Liu, A.D.; Li, J.W. Assessment of sugar-sweetened beverages consumption and free sugar intake among urban residents aged 3 and above in China. Chin. J. Food Hygiene 2022, 34, 126–130. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, H.; Zhao, L.; Xu, X.; Yu, W.; Ju, L.; Yu, D. Consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages among 18 years old and over adults in 2010–2012 in China. J. Hyg. Res. [Wei Sheng Yan Jiu] 2018, 47, 22–26. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Popkin, B.M. Global nutrition dynamics: The world is shifting rapidly toward a diet linked with noncommunicable diseases. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2006, 84, 289–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, G.M.; Micha, R.; Khatibzadeh, S.; Shi, P.; Lim, S.; Andrews, K.G.; Engell, R.E.; Ezzati, M.; Mozaffarian, D.; Global Burden of Diseases Nutrition and Chronic Diseases Expert Group (NutriCoDE). Global, Regional, and National Consumption of Sugar-Sweetened Beverages, Fruit Juices, and Milk: A Systematic Assessment of Beverage Intake in 187 Countries. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0124845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bleich, S.N.; Vercammen, K.A.; Koma, J.W.; Li, Z. Trends in Beverage Consumption among Children and Adults, 2003–2014. Obesity 2018, 26, 432–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontes, A.S.; Pallottini, A.C.; Vieira, D.A.d.S.; Fontanelli, M.d.M.; Marchioni, D.M.; Cesar, C.L.G.; Alves, M.C.G.P.; Goldbaum, M.; Fisberg, R.M. Demographic, socioeconomic and lifestyle factors associated with sugar-sweetened beverage intake: A population-based study. Rev. Bras. Epidemiol. 2020, 23, e200003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gui, Z.H.; Zhu, Y.N.; Cai, L.; Sun, F.H.; Ma, Y.H.; Jing, J.; Chen, Y.J. Sugar-Sweetened Beverage Consumption and Risks of Obesity and Hy-pertension in Chinese Children and Adolescents: A National Cross-Sectional Analysis. Nutrients 2017, 9, 1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, T.-F.; Lin, W.-T.; Huang, H.-L.; Lee, C.-Y.; Wu, P.-W.; Chiu, Y.-W.; Huang, C.-C.; Tsai, S.; Lin, C.-L.; Lee, C.-H. Consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages is associated with components of the metabolic syndrome in adolescents. Nutrients 2014, 6, 2088–2103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nathanson, C.A. Sex roles as variables in preventive health behavior. J. Community Health 1977, 3, 142–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foresight Industry Research Institute. Report of Development Prospect Prediction and Investment Strategy Planning on China New Tea Drinking Industry (2023–2028) [EB/OL]. (2023-06-13). Available online: https://bg.qianzhan.com/report/detail/1905081728257184.html (accessed on 2 May 2024).

- Barquera, S.; Campirano, F.; Bonvecchio, A.; Hernández-Barrera, L.; Rivera, J.A.; Popkin, B.M. Caloric beverage consumption patterns in Mexican children. Nutr. J. 2010, 9, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, E.; Kim, T.H.; Powell, L.M. Beverage consumption and individual-level associations in South Korea. BMC Public Health 2013, 13, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, E.; Powell, L.M. Consumption Patterns of Sugar-Sweetened Beverages in the United States. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2013, 113, 43–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hafekost, K.; Mitrou, F.; Lawrence, D.; Zubrick, S.R. Sugar sweetened beverage consumption by Australian children: Implications for public health strategy. BMC Public Health 2011, 11, 950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darmon, N.; Drewnowski, A. Contribution of food prices and diet cost to socioeconomic disparities in diet quality and health: A systematic review and analysis. Nutr. Rev. 2015, 73, 643–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tatangelo, G.; McCabe, M.; Campbell, S.; Szoeke, C. Gender, marital status and longevity. Maturitas 2017, 100, 64–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robles, T.F. Marital quality and health: Implications for marriage in the 21st century. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2014, 23, 427–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortez, G.R.; Lee, S.; Roberson, P.N.E. Get healthy to marry or marry to get healthy? Pers. Relatsh. 2020, 27, 613–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quan, S.; Zhang, H. The relationship between Marriage and Body Mass Index in China: Evidence from the China Health and Nutrition Survey. Econ. Hum. Biol. 2024, 53, 101368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turnic, T.N.; Jakovljevic, V.; Strizhkova, Z.; Polukhin, N.; Ryaboy, D.; Kartashova, M.; Korenkova, M.; Kolchina, V.; Reshetnikov, V. The Association between Marital Status and Obesity: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Diseases 2024, 12, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Male | Female | Total | χ2 (1) | p (2) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 3135 (49.03%) | 3259 (50.97%) | 6394 (100%) | ||

| Age | |||||

| 6–18 | 1053 (33.59%) | 1034 (31.73%) | 2087 (32.64%) | 3.987 | 0.263 |

| 18–40 | 748 (23.86%) | 770 (23.63%) | 1518 (23.74%) | ||

| 40–60 | 670 (21.37%) | 753 (23.11%) | 1423 (22.26%) | ||

| >60 | 664 (21.18%) | 702 (21.54%) | 1366 (21.36%) | ||

| Personal income | |||||

| low | 458 (22.00%) | 610 (27.42%) | 1068 (24.80%) | 52.02 | <0.001 |

| medium | 942 (45.24%) | 1099 (49.39%) | 2041 (47.39%) | ||

| high | 682 (32.76%) | 516 (23.19%) | 1198 (27.82%) | ||

| Education level | |||||

| low | 1263 (40.29%) | 1344 (41.24%) | 2607 (40.77%) | 4.67 | 0.099 |

| medium | 1310 (41.79%) | 1282 (39.34%) | 2592 (40.54%) | ||

| high | 562 (17.93%) | 633 (19.42%) | 1195 (18.690%) | ||

| Occupational status | |||||

| health-related industries | 607 (19.36%) | 710 (21.79%) | 1317 (20.60%) | 5.74 | 0.017 |

| others | 2528 (80.64%) | 2549 (78.21%) | 5077 (79.40%) | ||

| Marriage status | |||||

| bachelor | 1502 (47.91%) | 1423 (43.67%) | 2925 (45.75%) | 16.372 | <0.001 |

| married | 1569 (50.05%) | 1735 (53.24%) | 3304 (51.67%) | ||

| divorced/widowed | 64 (2.04%) | 101 (3.10%) | 165 (2.58%) | ||

| Obesity | |||||

| yes | 443 (14.13%) | 325 (9.97%) | 768 (12.01%) | 26.15 | <0.001 |

| no | 2692 (85.87%) | 2934 (90.03%) | 5626 (88.99%) | ||

| NCD (3) | |||||

| yes | 633 (20.19%) | 602 (18.47%) | 1235 (19.31%) | 3.03 | 0.082 |

| no | 2502 (79.81%) | 2657 (81.53%) | 5159 (80.69%) | ||

| Weight loss/shaping in the past month | |||||

| yes | 249 (7.94%) | 299 (9.18%) | 548 (8.57%) | 3.10 | 0.079 |

| no | 2886 (92.06%) | 2960 (90.83%) | 5846 (91.43%) | ||

| Mood swing in the past month | |||||

| yes | 72 (2.30%) | 81 (2.49%) | 153 (2.39%) | 0.24 | 0.621 |

| no | 3063 (97.70%) | 3178 (97.52%) | 6241 (97.61%) |

| Variables | TB (1) | SSB (2) | NSS (3) | RSB (4) | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Drink Rate (%) | p (5) | Consumption Amount Medium (P25, P75) | p | Drink Rate (%) | p | Consumption Amount Medium (P25, P75) | p | Drink Rate (%) | p | Consumption Amount Medium (P25, P75) | p | Drink Rate (%) | p | Consumption Amount Medium (P25, P75) | p | |

| Gender | 0.23 | <0.001 | 0.192 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.001 | 0.015 | 0.940 | ||||||||

| male | 58.30 | 175.71 (65.70, 396.56) | 57.80 | 160.97 (65.70, 359.83) | 20.50 | 32.85 (32.85, 85.71) | 28.50 | 32.85 (32.85, 142.86) | ||||||||

| female | 56.90 | 142.86 (52.56, 302.14) | 56.20 | 133.38 (49.28, 285.72) | 16.70 | 32.85 (21.68, 85.71) | 31.30 | 32.85 (32.85, 142.86) | ||||||||

| Age | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.056 | <0.001 | 0.001 | ||||||||

| 6–18 | 73.70 | 174.11 (65.70, 379.98) | 75.80 | 131.41 (39.42, 292.10) | 28.20 | 32.85 (32.85, 142.86) | 39.30 | 32.85 (32.85, 142.86) | ||||||||

| 18–40 | 70.70 | 176.14 (65.70, 384.27) | 69.40 | 165.85 (65.70, 357.14) | 25.00 | 32.85 (32.85, 142.86) | 40.00 | 32.85 (32.85, 142.86) | ||||||||

| 40–60 | 46.40 | 142.86 (45.99, 357.14) | 45.80 | 132.85 (45.99, 320.21) | 14.10 | 32.85 (32.85, 142.86) | 23.10 | 32.85 (32.85, 65.70) | ||||||||

| >60 | 28.80 | 77.43 (32.85, 215.13) | 28.70 | 72.92 (32.85, 214.29) | 5.20 | 32.85 (19.71, 96.42) | 8.30 | 32.85 (21.68, 131.41) | ||||||||

| Personal income | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.568 | <0.001 | 0.518 | ||||||||

| low | 40.20 | 134.00 (42.86, 301.42) | 39.50 | 129.99 (45.01, 282.85) | 11.00 | 32.85 (23.00, 94.29) | 17.50 | 32.85 (32.85, 137.13) | ||||||||

| medium | 45.50 | 134.00 (49.28, 318.57) | 44.90 | 128.27 (45.99, 289.89) | 12.60 | 32.85 (32.85, 131.41) | 22.10 | 32.85 (32.85, 98.55) | ||||||||

| high | 64.20 | 178.57 (65.70, 419.28) | 63.40 | 171.43 (65.70, 374.46) | 23.00 | 32.85 (32.85, 142.86) | 34.30 | 32.85 (32.85, 142.86) | ||||||||

| Education level | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.094 | <0.001 | 0.374 | ||||||||

| low | 53.40 | 131.41 (49.28, 294.24) | 53.80 | 101.99 (32.85, 241.77) | 15.90 | 32.85 (21.68, 142.86) | 22.80 | 32.85 (32.85, 142.86) | ||||||||

| medium | 57.20 | 177.40 (65.70, 416.55) | 57.70 | 156.00 (54.53, 357.14) | 20.90 | 32.85 (32.85, 142.86) | 31.50 | 32.85 (32.85, 142.86) | ||||||||

| high | 68.60 | 175.71 (65.70, 381.51) | 68.00 | 164.26 (65.70, 334.10) | 25.00 | 32.85 (26.28, 142.86) | 40.00 | 32.85 (32.85, 131.41) | ||||||||

| Occupational status | <0.001 | 0.004 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.102 | 0.003 | ||||||||

| health-related industries | 63.20 | 175.71 (65.70, 423.21) | 66.10 | 98.55 (32.85, 274.26) | 25.90 | 65.70 (32.85, 228.57) | 31.20 | 32.85 (29.07, 122.85) | ||||||||

| others | 56.10 | 154.40 (57.14, 342.14) | 55.60 | 142.86 (54.53, 314.98) | 17.80 | 32.85 (26.28, 100.00) | 29.00 | 32.85 (32.85, 142.86) | ||||||||

| Marriage status | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.324 | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||||||

| bachelor | 74.70 | 175.71 (65.70, 366.06) | 73.70 | 161.54 (65.70, 339.20) | 26.40 | 32.85 (29.57, 131.41) | 42.40 | 32.85 (32.85, 142.86) | ||||||||

| married | 43.40 | 131.41 (41.71, 307.11) | 42.80 | 118.27 (39.42, 285.71) | 12.00 | 32.85 (26.28, 98.55) | 19.30 | 32.85 (32.85, 98.55) | ||||||||

| divorced/widowed | 45.20 | 146.99 (46.98, 368.42) | 44.60 | 142.86 (44.02, 282.85) | 12.50 | 52.56 (21.68, 142.86) | 19.60 | 32.85 (26.28, 142.86) | ||||||||

| Obesity | 0.002 | <0.001 | 0.003 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.004 | 0.123 | 0.003 | ||||||||

| yes | 62.80 | 177.40 (65.70, 463.11) | 62.00 | 165.06 (65.70, 425.70) | 22.80 | 32.85 (32.85, 142.86) | 32.30 | 39.42 (32.85, 142.86) | ||||||||

| no | 56.90 | 151.76 (55.85, 328.68) | 56.30 | 142.86 (52.56, 305.43) | 18.00 | 32.85 (24.97, 98.55) | 29.60 | 32.85 (32.85, 142.86) | ||||||||

| NCD (6) | <0.001 | 0.850 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.014 | ||||||||

| yes | 41.00 | 161.10 (52.56, 405.67) | 43.90 | 65.70 (13.14, 236.81) | 15.30 | 124.84 (32.85, 357.14) | 16.90 | 32.85 (26.28, 98.55) | ||||||||

| no | 62.10 | 162.57 (61.42, 354.25) | 61.70 | 142.86 (55.85, 318.57) | 20.70 | 32.85 (27.43, 131.41) | 32.80 | 32.85 (32.85, 142.86) | ||||||||

| Weight loss/shaping in the past month | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.055 | <0.001 | 0.034 | ||||||||

| yes | 74.30 | 220.71 (98.55, 485.69) | 73.50 | 197.71 (91.33, 423.69) | 32.80 | 32.85 (32.85, 142.86) | 46.90 | 32.85 (32.85, 142.86) | ||||||||

| no | 56.20 | 151.12 (55.85, 342.86) | 56.50 | 131.41 (39.42, 289.75) | 18.40 | 32.85 (29.07, 142.86) | 27.90 | 32.85 (32.85, 142.86) | ||||||||

| Mood swing in the past month | 0.097 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.117 | <0.001 | ||||||||

| yes | 62.30 | 295.66 (127.14, 571.43) | 82.00 | 1.85 (0, 175.71) | 37.30 | 274.26 (65.70, 714.29) | 25.40 | 32.85 (19.71, 45.99) | ||||||||

| no | 57.30 | 153.09 (57.14, 342.86) | 56.70 | 142.86 (54.53, 318.57) | 18.50 | 32.85 (26.28, 107.14) | 30.70 | 32.85 (32.85, 142.86) | ||||||||

| All | 57.70 | 162.57 (59.13, 357.14) | 56.94 | 137.98 (45.99, 306.06) | 19.60 | 32.85 (32.85, 142.86) | 29.90 | 32.85 (32.85, 142.86) | ||||||||

| TB (1) | SSB (2) | NSS (3) | RSB (4) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β (5) | p | OR (5) | 95% CI (5) | β | p | OR | 95% CI | β | p | OR | 95% CI | β | p | OR | 95% CI | |

| Gender | ||||||||||||||||

| male | reference | reference | reference | reference | ||||||||||||

| female | −0.037 | 0.507 | 0.964 | 0.864–1.075 | −0.043 | 0.432 | 0.957 | 0.859–1.067 | −0.247 | <0.001 | 0.781 | 0.684–0.892 | 0.180 | 0.002 | 1.197 | 1.067–1.343 |

| Age | ||||||||||||||||

| 6–18 | reference | reference | reference | reference | ||||||||||||

| 18–40 | −0.536 | <0.001 | 0.585 | 0.476–0.720 | −0.574 | <0.001 | 0.563 | 0.459–0.691 | −0.537 | <0.001 | 0.584 | 0.469–0.729 | −0.509 | <0.001 | 0.601 | 0.494–0.732 |

| 40–60 | −1.171 | <0.001 | 0.310 | 0.241–0.400 | −1.163 | <0.001 | 0.312 | 0.243–0.402 | −0.866 | <0.001 | 0.421 | 0.314–0.564 | −0.859 | <0.001 | 0.423 | 0.328–0.547 |

| >60 | −1.653 | <0.001 | 0.191 | 0.147–0.249 | −1.626 | <0.001 | 0.197 | 0.152–0.255 | −1.651 | <0.001 | 0.192 | 0.134–0.274 | −1.783 | <0.001 | 0.168 | 0.124–0.228 |

| Education level | ||||||||||||||||

| low | reference | reference | reference | reference | ||||||||||||

| medium | 0.399 | <0.001 | 1.490 | 1.306–1.700 | 0.400 | <0.001 | 1.492 | 1.308–1.701 | 0.667 | <0.001 | 1.949 | 1.648–2.304 | 0.693 | <0.001 | 2.000 | 1.728–2.314 |

| high | 0.779 | <0.001 | 2.180 | 1.809–2.626 | 0.796 | <0.001 | 2.216 | 1.841–2.668 | 0.937 | <0.001 | 2.553 | 2.021–3.225 | 1.025 | <0.001 | 2.786 | 2.277–3.410 |

| Occupational status | ||||||||||||||||

| health-related industries | 0.261 | <0.001 | 1.298 | 1.127–1.496 | 0.229 | 0.001 | 1.257 | 1.092–1.446 | 0.158 | 0.061 | 0.848 | 0.992–1.381 | 0.096 | 0.197 | 1.101 | 0.951–1.274 |

| others | reference | reference | reference | reference | ||||||||||||

| Marriage status | ||||||||||||||||

| married | reference | reference | reference | reference | ||||||||||||

| bachelor | 0.439 | <0.001 | 1.551 | 1.266–1.899 | 0.433 | <0.001 | 1.542 | 1.262–1.884 | 0.362 | 0.001 | 1.437 | 1.152–1.792 | 0.526 | <0.001 | 1.692 | 1.393–2.055 |

| divorced/widowed | 0.300 | 0.079 | 1.350 | 0.965–1.888 | 0.291 | 0.088 | 1.338 | 0.957–1.871 | 0.268 | 0.305 | 1.307 | 0.783–2.181 | 0.345 | 0.108 | 1.412 | 0.927–2.151 |

| Obesity | ||||||||||||||||

| no | reference | reference | reference | reference | ||||||||||||

| yes | 0.132 | 0.132 | 1.141 | 0.961–1.354 | 0.128 | 0.143 | 1.136 | 0.958–1.347 | 0.175 | 0.078 | 1.191 | 0.981–1.447 | 0.039 | 0.666 | 1.039 | 0.872–1.238 |

| NCD | ||||||||||||||||

| no | reference | reference | reference | reference | ||||||||||||

| yes | −0.026 | 0.746 | 0.975 | 0.834–1.139 | −0.046 | 0.563 | 0.955 | 0.817–1.116 | 0.031 | 0.793 | 1.031 | 0.820–1.298 | 0.115 | 0.244 | 1.122 | 0.924–1.362 |

| Weight loss/shaping in the past month | ||||||||||||||||

| no | reference | reference | reference | reference | ||||||||||||

| yes | 0.533 | <0.001 | 1.704 | 1.375–2.111 | 0.534 | <0.001 | 1.706 | 1.380–2.110 | 0.618 | <0.001 | 1.855 | 1.510–2.278 | 0.526 | <0.001 | 1.692 | 1.396–2.051 |

| Mood swing in the past month | ||||||||||||||||

| no | reference | reference | reference | reference | ||||||||||||

| yes | 0.273 | 0.147 | 1.314 | 0.908–1.902 | 0.277 | 0.139 | 1.319 | 0.914–1.904 | −0.024 | 0.908 | 0.976 | 0.649–1.469 | 0.192 | 0.287 | 1.212 | 0.851–1.727 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, Z.; Shen, L.; Ning, J.; Sun, Z.; Xu, Y.; Shi, Z.; Song, Q.; Lu, W.; Ma, W.; Mai, S.; et al. The Consumption of Non-Sugar Sweetened and Ready-to-Drink Beverages as Emerging Types of Beverages in Shanghai. Nutrients 2024, 16, 3547. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16203547

Wang Z, Shen L, Ning J, Sun Z, Xu Y, Shi Z, Song Q, Lu W, Ma W, Mai S, et al. The Consumption of Non-Sugar Sweetened and Ready-to-Drink Beverages as Emerging Types of Beverages in Shanghai. Nutrients. 2024; 16(20):3547. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16203547

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Zhengyuan, Liping Shen, Jinpeng Ning, Zhuo Sun, Yiwen Xu, Zehuan Shi, Qi Song, Wei Lu, Wenqing Ma, Shupeng Mai, and et al. 2024. "The Consumption of Non-Sugar Sweetened and Ready-to-Drink Beverages as Emerging Types of Beverages in Shanghai" Nutrients 16, no. 20: 3547. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16203547

APA StyleWang, Z., Shen, L., Ning, J., Sun, Z., Xu, Y., Shi, Z., Song, Q., Lu, W., Ma, W., Mai, S., & Zang, J. (2024). The Consumption of Non-Sugar Sweetened and Ready-to-Drink Beverages as Emerging Types of Beverages in Shanghai. Nutrients, 16(20), 3547. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16203547