Consumption Trends and Eating Context of Lentils and Dried Peas in the United States: A Nationally Representative Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population

2.2. Identifying Consumers of Lentils and Dried Peas

2.3. Sociodemographic and Dietary Characteristics

2.4. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

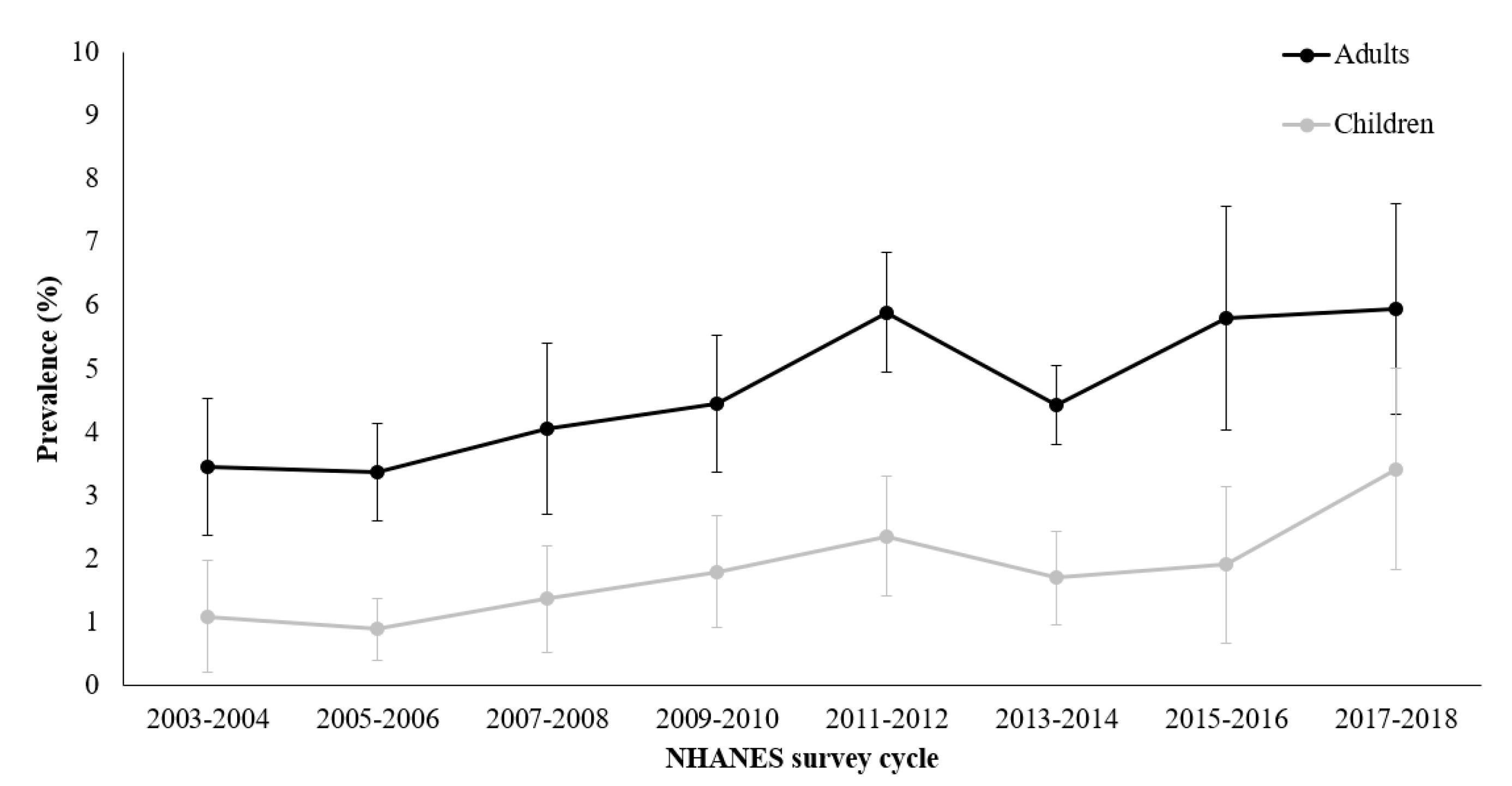

3.1. Trends in Prevalence of Lentils/Dried Peas Consumption in Adults and Children

3.2. Demographic Characteristics of Lentils/Dried Peas Consumers and Non-Consumers in NHANES 2017–2018

3.3. Eating Context of Lentils and Dried Peas in NHANES 2017–2018

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Afshin, A.; Sur, P.J.; Fay, K.A.; Cornaby, L.; Ferrara, G.; Salama, J.S.; Mullany, E.C.; Abate, K.H.; Abbafati, C.; Abebe, Z.; et al. Health effects of dietary risks in 195 countries, 1990–2017: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet 2019, 393, 1958–1972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Willett, W.; Rockström, J.; Loken, B.; Springmann, M.; Lang, T.; Vermeulen, S.; Garnett, T.; Tilman, D.; DeClerck, F.; Wood, A.; et al. Food in the Anthropocene: The EAT–Lancet Commission on healthy diets from sustainable food systems. Lancet 2019, 393, 447–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rao, M.; Afshin, A.; Singh, G.; Mozaffarian, D. Do healthier foods and diet patterns cost more than less healthy options? A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open 2013, 3, e004277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2020–2025 and Online Materials|Dietary Guidelines for Americans. Available online: https://www.dietaryguidelines.gov/resources/2020-2025-dietary-guidelines-online-materials (accessed on 7 April 2022).

- DASH Eating Plan|NHLBI, NIH. Available online: https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/education/dash-eating-plan (accessed on 7 April 2022).

- What Is the Mediterranean Diet?|American Heart Association. Available online: https://www.heart.org/en/healthy-living/healthy-eating/eat-smart/nutrition-basics/mediterranean-diet (accessed on 10 April 2022).

- Drewnowski, A. The Nutrient Rich Foods Index helps to identify healthy, affordable foods. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2010, 91, 1095S–1101S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drewnowski, A. The Contribution of Milk and Milk Products to Micronutrient Density and Affordability of the U.S. Diet. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 2011, 30, 422S–428S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drewnowski, A.; Rehm, C.D. Vegetable Cost Metrics Show That Potatoes and Beans Provide Most Nutrients Per Penny. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e63277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United States Department of Agriculture. MyPlate. Beans, Peas and Lentils. Available online: https://www.myplate.gov/eat-healthy/protein-foods/beans-peas-lentils (accessed on 18 November 2022).

- Sen Gupta, D.; Thavarajah, D.; Knutson, P.; Thavarajah, P.; McGee, R.J.; Coyne, C.J.; Kumar, S. Lentils (Lens culinaris L.), a Rich Source of Folates. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2013, 61, 7794–7799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, M.; Stronati, M.; Lanari, M. Mediterranean diet, folic acid, and neural tube defects. Ital. J. Pediatr. 2017, 43, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jukanti, A.K.; Gaur, P.M.; Gowda, C.L.L.; Chibbar, R.N. Nutritional quality and health benefits of chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.): A review. Br. J. Nutr. 2012, 108, S11–S26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganesan, K.; Xu, B. Polyphenol-Rich Lentils and Their Health Promoting Effects. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 2390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, N.; Johnson, C.R.; Thavarajah, P.; Kumar, S.; Thavarajah, D. The roles and potential of lentil prebiotic carbohydrates in human and plant health. Plants People Planet 2020, 2, 310–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mudryj, A.N.; Yu, N.; Aukema, H.M. Nutritional and health benefits of pulses. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 2014, 39, 1197–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitchell, D.C.; Lawrence, F.R.; Hartman, T.J.; Curran, J.M. Consumption of Dry Beans, Peas, and Lentils Could Improve Diet Quality in the US Population. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2009, 109, 909–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perera, T.; Russo, C.; Takata, Y.; Bobe, G. Legume Consumption Patterns in US Adults: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 2011–2014 and Beans, Lentils, Peas (BLP) 2017 Survey. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Semba, R.D.; Rahman, N.; Du, S.; Ramsing, R.; Sullivan, V.; Nussbaumer, E.; Love, D.; Bloem, M.W. Patterns of Legume Purchases and Consumption in the United States. Front. Nutr. 2021, 8, 732237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rehm, C.D.; Goltz, S.R.; Katcher, J.A.; Guarneiri, L.L.; Dicklin, M.R.; Maki, K.C. Trends and Patterns of Chickpea Consumption among United States Adults: Analyses of National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey Data. J. Nutr. 2023, 153, 1567–1576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Center for Health Statistics. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2021. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/index.htm (accessed on 11 November 2022).

- National Center for Health Statistics, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. NCHS Research Ethics Review Board (ERB) Approval. 2017. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/irba98.htm (accessed on 11 November 2022).

- National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. MEC In-Person Dietary Interviewers Procedures Manual; National Center for Health Statistics: Hyattsville, MD, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Ahluwalia, N.; Dwyer, J.; Terry, A.; Moshfegh, A.; Johnson, C. Update on NHANES Dietary Data: Focus on Collection, Release, Analytical Considerations, and Uses to Inform Public Policy. Adv. Nutr. 2016, 7, 121–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Dietary Interview—Individual Foods, First Day (DR1IFF_J). First Published June 2020. Available online: https://wwwn.cdc.gov/Nchs/Nhanes/2017-2018/DR1IFF_J.htm (accessed on 8 August 2022).

- National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Dietary Interview—Individual Foods, First Day (DR2IFF_J). First Published June 2020. Available online: https://wwwn.cdc.gov/Nchs/Nhanes/2017-2018/DR2IFF_J.htm (accessed on 8 August 2022).

- National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Dietary Interview Technical Support File—Food Codes (DRXFCD_J). First Published June 2020. Available online: https://wwwn.cdc.gov/Nchs/Nhanes/2017-2018/DRXFCD_J.htm (accessed on 8 August 2022).

- United States Department of Agriculture. Food Patterns Equivalents Database (FPED): Food Patterns Equivalents for Foods in the WWEIA, NHANES. Last Modified July 2023. Available online: https://www.ars.usda.gov/northeast-area/beltsville-md-bhnrc/beltsville-human-nutrition-research-center/food-surveys-research-group/docs/fped-databases/ (accessed on 8 August 2022).

- Krebs-Smith, S.M.; Pannucci, T.E.; Subar, A.F.; Kirkpatrick, S.I.; Lerman, J.L.; Tooze, J.A.; Wilson, M.M.; Reedy, J. Update of the Healthy Eating Index: HEI-2015. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2018, 118, 1591–1602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.-Y. Statistical notes for clinical researchers: Assessing normal distribution (2) using skewness and kurtosis. Restor. Dent. Endod. 2013, 38, 52–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmer, M.C.; Rubio, V.; Kintziger, K.W.; Barroso, C. Racial/Ethnic Disparities in Dietary Intake of U.S. Children Participating in WIC. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephenson, B.J.K.; Willett, W.C. Racial and ethnic heterogeneity in diets of low-income adult females in the United States: Results from National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys from 2011 to 2018. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2023, 117, 625–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Rompay, M.I.; McKeown, N.M.; Castaneda-Sceppa, C.; Falcón, L.M.; Ordovás, J.M.; Tucker, K.L. Acculturation and Sociocultural Influences on Dietary Intake and Health Status among Puerto Rican Adults in Massachusetts. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2012, 112, 64–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanjeevi, N. Mediation of the Relationship of Acculturation with Glycemic Control in Asian Americans with Diabetes. Am. J. Health Promot. 2022, 36, 279–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corral, I.; Landrine, H. Acculturation and ethnic-minority health behavior: A test of the operant model. Health Psychol. 2008, 27, 737–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heer, M.M.; Winham, D.M. Bean Preferences Vary by Acculturation Level among Latinas and by Ethnicity with Non-Hispanic White Women. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernando, S. Pulse protein ingredient modification. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2022, 102, 892–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanjeevi, N.; Freeland-Graves, J.H. Association of Grocery Expenditure Relative to Thrifty Food Plan Cost with Diet Quality of Women Participating in the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2018, 118, 2315–2323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- French, S.A.; Tangney, C.C.; Crane, M.M.; Wang, Y.; Appelhans, B.M. Nutrition quality of food purchases varies by household income: The SHoPPER study. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, H.W.; Vadiveloo, M.K. Diet quality of vegetarian diets compared with nonvegetarian diets: A systematic review. Nutr. Rev. 2019, 77, 144–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gittelsohn, J.; Rowan, M.; Gadhoke, P. Interventions in small food stores to change the food environment, improve diet, and reduce risk of chronic disease. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2012, 9, E59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setiono, F.J.; Gangrade, N.; Leak, T.M. U.S. Adolescents’ Diet Consumption Patterns Differ between Grocery and Convenience Stores: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2011–2018. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 8474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hebert, J.R.; Clemow, L.; Pbert, L.; Ockene, I.S.; Ockene, J.K. Social Desirability Bias in Dietary Self-Report May Compromise the Validity of Dietary Intake Measures. Int. J. Epidemiol. 1995, 24, 389–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Characteristics | Adults, Aged 18 Years or Older | Children, Aged 3–17 Years | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-Consumers (n = 4690) | Consumers (n = 293) | Non-Consumers (n = 1913) | Consumers (n = 58) | |

| Age | 46.9 ± 0.7 | 47.0 ± 1.7 | 10.2 ± 0.2 | 10.0 ± 0.9 |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 48.8 | 41.1 | 52.0 | 39.7 |

| Female | 51.2 | 58.9 | 48.0 | 60.3 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| Mexican American | 9.8 | 6.2 *** | 17.8 | 9.4 *** |

| Other Hispanic | 7.2 | 5.2 | 7.2 | 7.6 |

| Non-Hispanic White | 61.3 | 61.3 | 49.8 | 51.7 |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 11.7 | 4.0 | 12.4 | 5.0 |

| Non-Hispanic Asian | 5.2 | 20.7 | 4.3 | 22.3 |

| Other | 4.7 | 2.6 | 8.5 | 4.0 |

| Education level | ||||

| <9th grade | 3.6 | 2.5 *** | ||

| 9–11 grade | 7.2 | 2.7 | ||

| High school graduate | 28.9 | 11.2 | ||

| Some college/associate degree | 31.8 | 18.6 | ||

| College graduate or above | 28.6 | 65.0 | ||

| Language spoken at home (Hispanics) | ||||

| Only Spanish | 27.1 | 22.0 | ||

| More Spanish than English | 16.3 | 26.0 | ||

| Both equally | 15.0 | 14.9 | ||

| More English than Spanish | 16.1 | 13.6 | ||

| Only English | 25.5 | 23.5 | ||

| Language spoken at home (Asians) | ||||

| Only Non-English language | 39.5 | 48.4 | ||

| More Non-English than English | 10.9 | 9.7 | ||

| Both equally | 11.6 | 15.1 | ||

| More English than Non-English | 8.6 | 9.3 | ||

| Only English | 29.4 | 17.6 | ||

| Healthy Eating Index 2015 total score | 46.9 ± 0.7 | 60.2 ± 1.6 *** | 46.8 ± 0.5 | 58.8 ± 2.5 *** |

| Protein intake, % kilocalories | 16.1 ± 0.1 | 16.7 ± 0.8 | 14.4 ± 0.2 | 14.8 ± 1.1 |

| Vegetarian, based on dietary recall data | ||||

| No | 98.8 | 92.2 *** | 98.2 | 94.4 * |

| Yes | 1.2 | 7.8 | 1.8 | 5.6 |

| Income to poverty ratio | 3.0 ± 0.1 | 3.7 ± 0.2 *** | 2.4 ± 0.1 | 3.7 ± 0.3 *** |

| Food Source | Proportion of Occurrence (%) |

|---|---|

| Lentils | |

| Lentil curry (with or without rice) | 36.5 |

| Lentil soup | 33.5 |

| Lentils, from dried (with or without fat added) | 21.0 |

| Lentils, not further specified | 5.1 |

| White rice with lentils (with or without fat added) | 3.0 |

| Lentils, from canned | 1.0 |

| Peas | |

| Hummus, plain | 27.2 |

| Hummus, flavored | 24.9 |

| Chickpeas, not further specified | 14.3 |

| Blackeyed peas (canned or frozen) | 9.7 |

| Chickpeas, from dried (with or without fat) | 5.5 |

| Chickpeas, from canned (with or without fat) | 5.1 |

| Blackeyed peas, from dried | 4.2 |

| Split pea soup | 3.7 |

| Blackeyed peas, not further specified | 2.3 |

| Split pea and ham soup | 2.3 |

| Garbanzo bean or chickpea soup, home recipe, canned or ready-to-serve | 0.9 |

| Eating Occasion | Proportion of Occurrence (%) |

|---|---|

| Lentils | |

| Breakfast | 4.1 |

| Lunch/almuerzo | 38.6 |

| Dinner/cena | 48.8 |

| Supper | 2.4 |

| Snack/comida | 6.1 |

| Peas | |

| Breakfast | 3.2 |

| Lunch/almuerzo | 33.3 |

| Dinner/cena | 30.1 |

| Supper | 5.6 |

| Brunch | 2.3 |

| Snack/comida/entre comida/botana | 25.5 |

| Eating Occasion | Proportion of Occurrence (%) |

|---|---|

| Lentils | |

| Grocery store/supermarket | 84.8 |

| Restaurant/fast food joint | 9.5 |

| Convenience store | 2.7 |

| Cafeteria (school or outside school)/child or adult care center | 1.0 |

| From someone else | 2.0 |

| Peas | |

| Grocery store/supermarket | 73.6 |

| Restaurant/fast food joint | 11.6 |

| Cafeteria (school or outside school) | 6.5 |

| From someone else | 6.0 |

| Convenience store | 1.4 |

| Grown by self/others | 0.5 |

| Common snack tray | 0.5 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sanjeevi, N.; Monsivais, P. Consumption Trends and Eating Context of Lentils and Dried Peas in the United States: A Nationally Representative Study. Nutrients 2024, 16, 277. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16020277

Sanjeevi N, Monsivais P. Consumption Trends and Eating Context of Lentils and Dried Peas in the United States: A Nationally Representative Study. Nutrients. 2024; 16(2):277. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16020277

Chicago/Turabian StyleSanjeevi, Namrata, and Pablo Monsivais. 2024. "Consumption Trends and Eating Context of Lentils and Dried Peas in the United States: A Nationally Representative Study" Nutrients 16, no. 2: 277. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16020277

APA StyleSanjeevi, N., & Monsivais, P. (2024). Consumption Trends and Eating Context of Lentils and Dried Peas in the United States: A Nationally Representative Study. Nutrients, 16(2), 277. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16020277