Complementary Feeding Practices: Recommendations of Pediatricians for Infants with and without Allergy Risk

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Questionnaire

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Participants

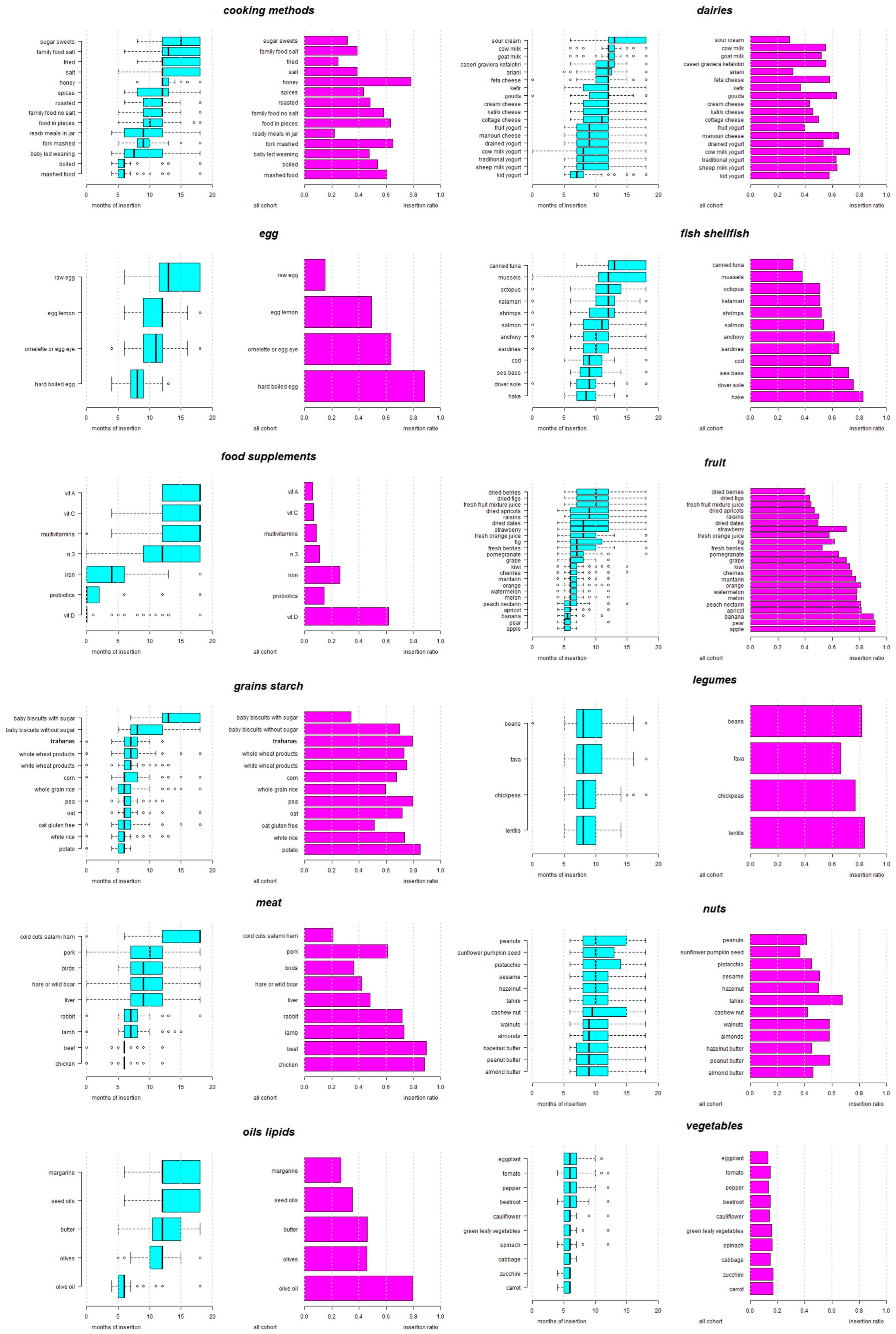

3.2. Infant Feeding Practices: The Order of Introduction of Solid Food Recommended by the Pediatricians

3.3. The Influence of Years of Pediatric Practice on the Order of Food Introduction

3.4. The Influence of Sex of the Pediatrician on the Order of Food Introduction

3.5. The Influence of the Area of Practice on the Order of Food Introduction

3.6. The Influence of Parenthood on the Order of Food Introduction

3.7. Differences in Recommendations of Pediatricians on Food Introduction, according to High and Low Risk of Allergy

3.8. Factors Associated with Recommendation of a Longer Time Period between Introduction of New Foods

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. Complementary Feeding. 2023. Available online: https://www.who.int/health-topics/complementary-feeding#tab=tab_1 (accessed on 10 September 2023).

- CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention). Weaning. Nutrition. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/nutrition/InfantandToddlerNutrition/breastfeeding/weaning.html (accessed on 10 September 2023).

- Greek Ministry of Health. Recommendations for the Introduction of Solid Foods in the 1st Year of Life. 2018. Available online: https://www.moh.gov.gr/articles/health/dieythynsh-dhmosias-ygieinhs/metadotika-kai-mh-metadotika-noshmata/c388-egkyklioi/5750-systaseis-gia-thn-eisagwgh-sterewn-trofwn-ston-1o-xrono-ths-zwhs (accessed on 10 September 2023).

- Agostoni, C.; Decsi, T.; Fewtrell, M.; Goulet, O.; Kolacek, S.; Koletzko, B.; Michaelsen, K.F.; Moreno, L.; Puntis, J.; Rigo, J.; et al. Complementary feeding: A commentary by the espghan committee on nutrition. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2008, 46, 99–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lutter, C.K.; Grummer-Strawn, L.; Rogers, L. Complementary feeding of infants and young children 6 to 23 months of age. Nutr. Rev. 2021, 79, 825–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alvisi, P.; Congiu, M.; Ficara, M.; De Gregorio, P.; Ghio, R.; Spisni, E.; Di Saverio, P.; Labriola, F.; Lacorte, D.; Lionetti, P. Complementary feeding in italy: From tradition to innovation. Children 2021, 8, 638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Auria, E.; Bergamini, M.; Staiano, A.; Banderali, G.; Pendezza, E.; Penagini, F.; Zuccotti, G.V.; Peroni, D.G. Baby-led weaning: What a systematic review of the literature adds on. Ital. J. Pediatr. 2018, 44, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fewtrell, M.; Bronsky, J.; Campoy, C.; Domellöf, M.; Embleton, N.; Mis, N.F.; Hojsak, I.; Hulst, J.M.; Indrio, F.; Lapillonne, A.; et al. Complementary feeding: A position paper by the european society for paediatric gastroenterology, hepatology, and nutrition (espghan) committee on nutrition. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2017, 64, 119–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devonshire, A.L.; Robison, R.G. Prevention of food allergy. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2019, 40, 450–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prescott, S.L.; Smith, P.; Tang, M.; Palmer, D.J.; Sinn, J.; Huntley, S.J.; Cormack, B.; Heine, R.G.; Gibson, R.A.; Makrides, M. The importance of early complementary feeding in the development of oral tolerance: Concerns and controversies. Pediatr. Allergy Immunol. 2008, 19, 375–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perkin, M.R.; Logan, K.; Tseng, A.; Raji, B.; Ayis, S.; Peacock, J.; Brough, H.; Marrs, T.; Radulovic, S.; Craven, J.; et al. Randomized trial of introduction of allergenic foods in breast-fed infants. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 374, 1733–1743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du Toit, G.; Roberts, G.; Sayre, P.H.; Bahnson, H.T.; Radulovic, S.; Santos, A.F.; Brough, H.A.; Phippard, D.; Basting, M.; Feeney, M.; et al. Randomized trial of peanut consumption in infants at risk for peanut allergy. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 372, 803–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellach, J.; Schwarz, V.; Ahrens, B.; Trendelenburg, V.; Aksünger, Ö.; Kalb, B.; Niggemann, B.; Keil, T.; Beyer, K. Randomized placebo-controlled trial of hen’s egg consumption for primary prevention in infants. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2017, 139, 1591–1599.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, D.J.; Metcalfe, J.; Makrides, M.; Gold, M.S.; Quinn, P.; West, C.E.; Loh, R.; Prescott, S.L. Early regular egg exposure in infants with eczema: A randomized controlled trial. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2013, 132, 387–392.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palmer, D.J.; Sullivan, T.R.; Gold, M.S.; Prescott, S.L.; Makrides, M. Randomized controlled trial of early regular egg intake to prevent egg allergy. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2017, 139, 1600–1607.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, W.-L.; Valerio, C.; Barnes, E.H.; Turner, P.J.; Van Asperen, P.A.; Kakakios, A.M.; Campbell, D.E. A randomized trial of egg introduction from 4 months of age in infants at risk for egg allergy. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2017, 139, 1621–1628.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natsume, O.; Kabashima, S.; Nakazato, J.; Yamamoto-Hanada, K.; Narita, M.; Kondo, M.; Saito, M.; Kishino, A.; Takimoto, T.; Inoue, E.; et al. Two-step egg introduction for prevention of egg allergy in high-risk infants with eczema (petit): A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2017, 389, 276–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hesselmar, B.; Saalman, R.; Rudin, A.; Adlerberth, I.; Wold, A. Early fish introduction is associated with less eczema, but not sensitization, in infants. Acta Paediatr. 2010, 99, 1861–1867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papamichael, M.M.; Shrestha, S.K.; Itsiopoulos, C.; Erbas, B. The role of fish intake on asthma in children: A meta-analysis of observational studies. Pediatr. Allergy Immunol. 2018, 29, 350–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ierodiakonou, D.; Garcia-Larsen, V.; Logan, A.; Groome, A.; Cunha, S.; Chivinge, J.; Robinson, Z.; Geoghegan, N.; Jarrold, K.; Reeves, T.; et al. Timing of allergenic food introduction to the infant diet and risk of allergic or autoimmune disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA 2016, 316, 1181–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scarpone, R.; Kimkool, P.; Ierodiakonou, D.; Leonardi-Bee, J.; Garcia-Larsen, V.; Perkin, M.R.; Boyle, R.J. Timing of allergenic food introduction and risk of immunoglobulin e–mediated food allergy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr. 2023, 177, 489–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venter, C.; Pereira, B.; Voigt, K.; Grundy, J.; Clayton, C.B.; Higgins, B.; Arshad, S.H.; Dean, T. Factors associated with maternal dietary intake, feeding and weaning practices, and the development of food hypersensitivity in the infant. Pediatr. Allergy Immunol. 2009, 20, 320–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sellen, D.W. Evolution of infant and young child feeding: Implications for contemporary public health. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 2007, 27, 123–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borowitz, S.M. First bites-why, when, and what solid foods to feed infants. Front. Pediatr. 2021, 9, 654171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuzzi, G.; Gerini, C.; Comberiati, P.; Peroni, D.G. The weaning practices: A new challenge for pediatricians? Pediatr. Allergy Immunol. 2022, 33 (Suppl. S27), 44–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- King, C. An evidence based guide to weaning preterm infants. Paediatr. Child Health 2009, 19, 405–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samady, W.; Campbell, E.; Aktas, O.N.; Jiang, J.; Bozen, A.; Fierstein, J.L.; Joyce, A.H.; Gupta, R.S. Recommendations on complementary food introduction among pediatric practitioners. JAMA Netw. Open 2020, 3, e2013070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grueger, B. Weaning from the breast. Paediatr. Child Health 2013, 18, 210–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koplin, J.J.; Osborne, N.J.; Wake, M.; Martin, P.E.; Gurrin, L.C.; Robinson, M.N.; Tey, D.; Slaa, M.; Thiele, L.; Miles, L.; et al. Can early introduction of egg prevent egg allergy in infants? A population-based study. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2010, 126, 807–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Lauzon-Guillain, B.; Jones, L.; Oliveira, A.; Moschonis, G.; Betoko, A.; Lopes, C.; Moreira, P.; Manios, Y.; Papadopoulos, N.G.; Emmett, P.; et al. The influence of early feeding practices on fruit and vegetable intake among preschool children in 4 european birth cohorts. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2013, 98, 804–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romero-Velarde, E.; Villalpando-carrion, S.; Pérez-Lizaur, A.B.; Iracheta-Gerez, M.D.L.L.; Alonso-Rivera, C.G.; López-Navarrete, G.E.; García-Contreras, A.A.; Ochoa-Ortiz, E.; Zárate-mondragón, F.; López-Pérez, G.T.; et al. Guidelines for complementary feeding in healthy infants. Boletín Médico Hosp. Infant. México 2016, 73, 338–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scaglioni, S.; De Cosmi, V.; Ciappolino, V.; Parazzini, F.; Brambilla, P.; Agostoni, C. Factors influencing children’s eating behaviours. Nutrients 2018, 10, 706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mameli, C.; Mazzantini, S.; Zuccotti, G.V. Nutrition in the first 1000 days: The origin of childhood obesity. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2016, 13, 838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajmal, S.; Ajmal, L.; Ajmal, M.; Nawaz, G. Association of malnutrition with weaning practices among infants in pakistan. Cureus 2022, 14, e31018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trogen, B.; Jacobs, S.; Nowak-Wegrzyn, A. Early introduction of allergenic foods and the prevention of food allergy. Nutrients 2022, 14, 2565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferraro, V.; Zanconato, S.; Carraro, S. Timing of food introduction and the risk of food allergy. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giovannini, M.; Riva, E.; Banderali, G.; Scaglioni, S.; Veehof, S.; Sala, M.; Radaelli, G.; Agostoni, C. Feeding practices of infants through the first year of life in italy. Acta Paediatr. 2004, 93, 492–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caroli, M.; Mele, R.M.; Tomaselli, M.A.; Cammisa, M.; Longo, F.; Attolini, E. Complementary feeding patterns in europe with a special focus on italy. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2012, 22, 813–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guandalini, S. The influence of gluten: Weaning recommendations for healthy children and children at risk for celiac disease. Nestle Nutr. Workshop Ser. Pediatr. Program. 2007, 60, 139–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logan, K.; Perkin, M.R.; Marrs, T.; Radulovic, S.; Craven, J.; Flohr, C.; Bahnson, H.T.; Lack, G. Early gluten introduction and celiac disease in the eat study: A prespecified analysis of the eat randomized clinical trial. JAMA Pediatr. 2020, 174, 1041–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, A.; Meisenheimer, E.S.; Marshall, R.C. Can early introduction of gluten reduce risk of celiac disease? J. Fam. Pract. 2022, 71, E4–E6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazos, E.S.; Aggelousis, G.; Bratakos, M. The fermentation of trahanas: A milk-wheat flour combination. Plant Foods Hum. Human. Nutr. 1993, 44, 45–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Mecherfi, K.-E.; Todorov, S.D.; de Albuquerque, M.A.C.; Denery-Papini, S.; Lupi, R.; Haertlé, T.; de Melo Franco, B.D.G.; Larré, C. Allergenicity of fermented foods: Emphasis on seeds protein-based products. Foods 2020, 9, 792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uncuoglu, A.; Yologlu, N.; Simsek, I.E.; Uyan, Z.S.; Aydogan, M. Tolerance to baked and fermented cow’s milk in children with ige-mediated and non-ige-mediated cow’s milk allergy in patients under two years of age. Allergol. Immunopathol. 2017, 45, 560–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koksal, Z.G.; Uysal, P.; Mercan, A.; Bese, S.A.; Erge, D. Does maternal fermented dairy products consumption protect against cow’s milk protein allergy in toddlers? Ann. Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2023, 130, 333–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okoniewski, A.; Dobrzyńska, M.; Kusyk, P.; Dziedzic, K.; Przysławski, J.; Drzymała-Czyż, S. The role of fermented dairy products on gut microbiota composition. Fermentation 2023, 9, 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bustillos, B.; Sharkey, J.R.; Anding, J.; McIntosh, A. Availability of more healthful food alternatives in traditional, convenience, and nontraditional types of food stores in two rural texas counties. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2009, 109, 883–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pachón, H.; Simondon, K.B.; Fall, S.T.; Menon, P.; Ruel, M.T.; Hotz, C.; Creed-Kanashiro, H.; Arce, B.; Domínguez, M.R.; Frongillo, E.A.; et al. Constraints on the delivery of animal-source foods to infants and young children: Case studies from five countries. Food Nutr. Bull. 2007, 28, 215–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casari, S.; Di Paola, M.; Banci, E.; Diallo, S.; Scarallo, L.; Renzo, S.; Gori, A.; Renzi, S.; Paci, M.; de Mast, Q.; et al. Changing dietary habits: The impact of urbanization and rising socio-economic status in families from burkina faso in sub-saharan africa. Nutrients 2022, 14, 1782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roduit, C.; Frei, R.; Depner, M.; Schaub, B.; Loss, G.; Genuneit, J.; Pfefferle, P.; Hyvärinen, A.; Karvonen, A.M.; Riedler, J.; et al. Increased food diversity in the first year of life is inversely associated with allergic diseases. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2014, 133, 1056–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roduit, C.; Frei, R.; Loss, G.; Büchele, G.; Weber, J.; Depner, M.; Loeliger, S.; Dalphin, M.L.; Roponen, M.; Hyvärinen, A.; et al. Development of atopic dermatitis according to age of onset and association with early-life exposures. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2012, 130, 130–136.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nwaru, B.I.; Erkkola, M.; Ahonen, S.; Kaila, M.; Haapala, A.M.; Kronberg-Kippilä, C.; Salmelin, R.; Veijola, R.; Ilonen, J.; Simell, O.; et al. Age at the introduction of solid foods during the first year and allergic sensitization at age 5 years. Pediatrics 2010, 125, 50–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nwaru, B.I.; Takkinen, H.M.; Niemelä, O.; Kaila, M.; Erkkola, M.; Ahonen, S.; Haapala, A.M.; Kenward, M.G.; Pekkanen, J.; Lahesmaa, R.; et al. Timing of infant feeding in relation to childhood asthma and allergic diseases. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2013, 131, 78–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmeira, P.; Carneiro-Sampaio, M. Immunology of breast milk. Rev. Assoc. Med. Bras. 2016, 62, 584–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreno-Galarraga, L.; Martín-Álvarez, I.; Fernández-Montero, A.; Rocha, B.S.; Barea, E.C.; Martín-Calvo, N. Consumption of ultra-processed products and wheezing respiratory diseases in children: The sendo project. Anales de Pediatría (Engl. Ed.) 2021, 95, 18–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kong, W.; Xie, Y.; Zhong, J.; Cao, C. Ultra-processed foods and allergic symptoms among children and adults in the united states: A population-based analysis of nhanes 2005–2006. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 1038141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boundy, E.O.; Boyd, A.F.; Hamner, H.C.; Belay, B.; Liebhart, J.L.; Lindros, J.; Hassink, S.; Frintner, M.P. Us pediatrician practices on early nutrition, feeding, and growth. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2020, 52, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, R.S.; Bilaver, L.A.; Johnson, J.L.; Hu, J.W.; Jiang, J.; Bozen, A.; Martin, J.; Reese, J.; Cooper, S.F.; Davis, M.M.; et al. Assessment of pediatrician awareness and implementation of the addendum guidelines for the prevention of peanut allergy in the united states. JAMA Netw. Open 2020, 3, e2010511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leo, S.; Dean, J.; Chan, E.S. What are the beliefs of pediatricians and dietitians regarding complementary food introduction to prevent allergy? Allergy Asthma Clin. Immunol. 2012, 8, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elbert, N.J.; Jong, J.C.K.-D.; Voortman, T.; Nijsten, T.E.C.; de Jong, N.W.; Jaddoe, V.W.V.; de Jongste, J.C.; van Wijk, R.G.; Duijts, L.; Pasmans, S.G.M.A. Allergenic food introduction and risk of childhood atopic diseases. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0187999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.K.; Liu, Z.; Huang, C.K.; Wu, T.C.; Huang, C.F. Prevalence, clinical presentation, and associated atopic diseases of pediatric fruit and vegetable allergy: A population-based study. Pediatr. Neonatol. 2022, 63, 520–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleinman, R.E.; Coletta, F.A. Historical overview of transitional feeding recommendations and vegetable feeding practices for infants and young children. Nutr. Today 2016, 51, 7–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldassarre, M.E.; Palladino, V.; Amoruso, A.; Pindinelli, S.; Mastromarino, P.; Fanelli, M.; Di Mauro, A.; Laforgia, N. Rationale of probiotic supplementation during pregnancy and neonatal period. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simeone, G.; Bergamini, M.; Verga, M.C.; Cuomo, B.; D’Antonio, G.; Iacono, I.D.; Mauro, D.D.; Mauro, F.D.; Mauro, G.D.; Leonardi, L.; et al. Do vegetarian diets provide adequate nutrient intake during complementary feeding? A systematic review. Nutrients 2022, 14, 3591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calamaro, C.J. Infant nutrition in the first year of life: Tradition or science? Pediatr. Nurs. 2000, 26, 211–215. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Dembiński, Ł.; Banaszkiewicz, A.; Dereń, K.; Pituch-Zdanowska, A.; Jackowska, T.; Walkowiak, J.; Mazur, A. Exploring physicians’ perspectives on the introduction of complementary foods to infants and toddlers. Nutrients 2021, 13, 3559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Białek-Dratwa, A.; Kowalski, O.; Szczepańska, E. Traditional complementary feeding or blw (baby led weaning) method?—A cross-sectional study of polish infants during complementary feeding. Front. Pediatr. 2022, 10, 992244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, A.; Jones, S.W.; Rowan, H. Baby-led weaning: The evidence to date. Curr. Nutr. Rep. 2017, 6, 148–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boswell, N. Complementary feeding methods-a review of the benefits and risks. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 7165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Białek-Dratwa, A.; Soczewka, M.; Grajek, M.; Szczepańska, E.; Kowalski, O. Use of the baby-led weaning (blw) method in complementary feeding of the infant-a cross-sectional study of mothers using and not using the blw method. Nutrients 2022, 14, 2372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Committee on Injury, Violence, and Poison Prevention. Prevention of choking among children. Pediatrics 2010, 125, 601–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golnik, A.; Ireland, M.; Borowsky, I.W. Medical homes for children with autism: A physician survey. Pediatrics 2009, 123, 966–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Food | Low Pediatric Experience (<15 Years) N = 112 Month of Age | High Pediatric Experience (≥15 Years) N = 121 Month of Age | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Raisins | 10 (7–12) | 8 (6–12) | 0.048 |

| Fresh mixed fruit juice | 12 (8–12) | 8 (6–12) | 0.004 |

| White rice | 6 (6–7) | 6 (5–6) | 0.002 |

| Rabbit | 6 (6–7) | 7 (6–8) | 0.035 |

| Lamb | 6 (6–7) | 7 (6–9) | 0.007 |

| Beef | 6 (6–6) | 6 (6–7) | 0.024 |

| Pork | 9 (7–12) | 12 (8–12) | 0.036 |

| Omelet or fried egg | 10 (8–12) | 12 (10–12) | 0.019 |

| Raw egg | 18 (12–18) | 12 (9–13) | 0.009 |

| Cow’s milk | 12 (12–12) | 12 (12–18) | 0.038 |

| Traditional yogurt | 7 (7–10) | 10 (7–12) | 0.022 |

| Sheep’s milk yogurt | 7 (7–9) | 9 (7–12) | 0.024 |

| Manouri cheese | 8 (7–12) | 10 (8–12) | 0.047 |

| Beans | 8 (7–10) | 9 (8–12) | 0.019 |

| Lentils | 8 (7–9) | 9 (7–10) | <0.001 |

| Chickpeas | 8 (7–10) | 9 (7–12) | 0.002 |

| Anchovy | 9 (8–12) | 12 (8–12) | 0.031 |

| Calamari | 12 (9–12) | 13 (12–18) | <0.001 |

| Octopus | 12 (8–12) | 13 (12–18) | <0.001 |

| Shrimps | 12 (8–12) | 12 (12–15) | <0.001 |

| Mussels | 12 (9–13) | 13 (12–18) | 0.001 |

| Omega-3 | 13 (12–18) | 4 (0–11) | <0.001 |

| Multivitamins | 18 (18–18) | 9 (4–13) | 0.033 |

| Vitamin C | 18 (15–18) | 6 (5–9) | 0.009 |

| Food | Male N = 56 | Female N = 177 | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fig | 6 (6–10) | 8 (6–12) | 0.048 |

| Kiwi | 6 (5–6) | 6 (6–8) | 0.003 |

| Pomegranate | 6 (5–8) | 7 (6–9) | 0.023 |

| Raisins | 6 (6–10) | 10 (7–12) | 0.006 |

| Soft egg, omelet or fried egg | 12 (10–12) | 10 (9–12) | 0.025 |

| Fruit yogurt | 7 (6–12) | 11 (8–12) | 0.042 |

| Kids’ yogurt | 7 (6–7) | 7 (6–8) | 0.037 |

| Katiki cheese | 10 (8–12) | 12 (8–12) | 0.006 |

| Ariani | 12 (6–12) | 12 (12–13) | 0.049 |

| Olive oil | 6 (6–6) | 6 (5–6) | 0.001 |

| Baby biscuits with sugar | 12 (11–14) | 13 (12–18) | 0.044 |

| Boiled food | 6 (6–6) | 6 (5–6) | 0.014 |

| Mashed food | 6 (6–8) | 6 (5–6) | 0.002 |

| p-Value | OR | 95% CI * | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Experience (<15 years) | ||||

| Orange | 0.02 | 0.32 | 0.12 | 0.86 |

| Kiwi | 0.04 | 0.44 | 0.20 | 0.95 |

| Strawberry | 0.04 | 0.44 | 0.20 | 0.95 |

| Hard-boiled egg | 0.04 | 0.53 | 0.29 | 0.98 |

| Wheat (gluten) products | 0.007 | 0.35 | 0.17 | 0.75 |

| Frumenty | 0.02 | 0.51 | 0.29 | 0.91 |

| Cow’s milk yogurt | 0.02 | 0.43 | 0.21 | 0.87 |

| Peanuts/peanut butter | 0.001 | 0.21 | 0.09 | 0.52 |

| Hazelnut butter | 0.03 | 0.31 | 0.11 | 0.89 |

| Pistachios | 0.04 | 0.42 | 0.18 | 0.94 |

| Almonds/almond butter | 0.003 | 0.23 | 0.08 | 0.61 |

| Sesame/tahini | <0.001 | 0.15 | 0.05 | 0.40 |

| Beans | 0.01 | 0.17 | 0.04 | 0.64 |

| Seafood | <0.001 | 0.18 | 0.08 | 0.42 |

| Location (rural/semi-urban) | ||||

| Almonds/almond butter | 0.04 | 0.43 | 0.19 | 0.96 |

| Walnuts | 0.04 | 0.48 | 0.23 | 0.98 |

| Sesame/tahini | 0.04 | 0.46 | 0.22 | 0.97 |

| Hazelnuts/hazelnut butter | 0.02 | 0.33 | 0.12 | 0.85 |

| Seafood | 0.009 | 0.06 | 0.01 | 0.51 |

| Beans | 0.001 | 0.16 | 0.05 | 0.49 |

| Lentils | 0.01 | 0.07 | 0.01 | 0.54 |

| Tomato | 0.03 | 0.07 | 0.01 | 0.80 |

| Subspecialty (No) | ||||

| Orange | <0.001 | 0.18 | 0.08 | 0.40 |

| Kiwi | <0.001 | 0.29 | 0.15 | 0.56 |

| Strawberry | <0.001 | 0.29 | 0.15 | 0.56 |

| Hard-boiled egg | 0.03 | 0.56 | 0.33 | 0.95 |

| Soft egg/omelet/fried egg | 0.004 | 20.49 | 10.32 | 40.66 |

| Cream cheese | 0.03 | 20.28 | 10.08 | 40.81 |

| Gouda cheese | 0.04 | 0.49 | 0.25 | 0.96 |

| Almonds/almond butter | <0.001 | 0.22 | 0.10 | 0.48 |

| Walnuts | 0.01 | 0.40 | 0.20 | 0.81 |

| Beans | 0.002 | 0.23 | 0.09 | 0.58 |

| Lentils | 0.001 | 0.08 | 0.02 | 0.38 |

| Seafood | 0.002 | 0.10 | 0.02 | 0.43 |

| Parenthood (No) | ||||

| Cow’s milk | 0.04 | 0.26 | 0.07 | 0.95 |

| Wheat (gluten) products | 0.03 | 3.27 | 1.14 | 9.37 |

| Sex (Male) | ||||

| Gouda cheese | 0.02 | 0.24 | 0.06 | 0.83 |

| Wheat (gluten) products | 0.01 | 0.15 | 0.03 | 0.67 |

| Kiwi | 0.01 | 0.15 | 0.03 | 0.67 |

| Strawberry | 0.01 | 0.15 | 0.03 | 0.67 |

| Time between New Foods | p-Value | OR | 95% CI * | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Healthy infants (high) | Sex, male | 0.04 | 1.89 | 1.03 | 3.47 |

| Infants at risk for allergy | Subspecialty (no) | <0.001 | 5.91 | 3.05 | 11.43 |

| Location (rural) | 0.002 | 2.90 | 1.47 | 5.70 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Vassilopoulou, E.; Feketea, G.; Pagkalos, I.; Rallis, D.; Milani, G.P.; Agostoni, C.; Douladiris, N.; Lakoumentas, J.; Stefanaki, E.; Efthymiou, Z.; et al. Complementary Feeding Practices: Recommendations of Pediatricians for Infants with and without Allergy Risk. Nutrients 2024, 16, 239. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16020239

Vassilopoulou E, Feketea G, Pagkalos I, Rallis D, Milani GP, Agostoni C, Douladiris N, Lakoumentas J, Stefanaki E, Efthymiou Z, et al. Complementary Feeding Practices: Recommendations of Pediatricians for Infants with and without Allergy Risk. Nutrients. 2024; 16(2):239. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16020239

Chicago/Turabian StyleVassilopoulou, Emilia, Gavriela Feketea, Ioannis Pagkalos, Dimitrios Rallis, Gregorio Paolo Milani, Carlo Agostoni, Nikolaos Douladiris, John Lakoumentas, Evangelia Stefanaki, Zenon Efthymiou, and et al. 2024. "Complementary Feeding Practices: Recommendations of Pediatricians for Infants with and without Allergy Risk" Nutrients 16, no. 2: 239. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16020239

APA StyleVassilopoulou, E., Feketea, G., Pagkalos, I., Rallis, D., Milani, G. P., Agostoni, C., Douladiris, N., Lakoumentas, J., Stefanaki, E., Efthymiou, Z., & Tsabouri, S. (2024). Complementary Feeding Practices: Recommendations of Pediatricians for Infants with and without Allergy Risk. Nutrients, 16(2), 239. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16020239