Abstract

Households with limited financial resources often struggle with inadequate access to healthy, affordable food. Community supported agriculture (CSA) has the potential to improve access to fresh fruits and vegetables, yet low-income households seldom participate due to cost and other barriers. Cost-offset (or subsidized) CSA reduces financial barriers, yet engagement varies widely among those who enroll. This scoping review explored factors associated with CSA participation among low-income households in the United States. Eighteen articles met the inclusion criteria, quantitative and qualitative data were extracted, the evidence was synthesized, and themes were developed. The findings suggested that women may be more likely than men to enroll in CSA. A lack of familiarity with CSA may hinder enrollment, whereas more education and self-efficacy for food preparation may facilitate participation. In terms of share contents, high-quality produce, a variety of items, more fruit, a choice of share contents, and a choice of share sizes may facilitate participation. In terms of CSA operations, a low price, good value, acceptance of Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) benefits, close pick-up locations on existing travel routes, delivery of shares, clear communication, fostering a sense of belonging and trust, and educational support may support participation. Together these findings support 13 recommendations for cost-offset CSA implementation to engage low-income households.

1. Introduction

Fruits and vegetables (FVs) are known to have multiple health benefits [1] and are an important component of dietary recommendations [2]. However, adults and children in food insecure households and those with low household incomes consume fewer fruits and vegetables than their higher income counterparts who have more resources and greater food security [3,4,5,6,7,8,9]. Recent data suggest that only 6.8% of adults living in poverty meet vegetable intake recommendations [9]. Public health practitioners seek ways to improve access to affordable FVs to support health.

Community supported agriculture (CSA) is one approach to improving access to fresh, whole FVs. CSA brings local farms and households together, typically through an advance purchase of a share of the farm’s anticipated harvest [10]. However, low-income households seldom enroll in CSA due to up-front payments, cost, and other barriers [11,12]. Critics have stated that CSA reproduces social hierarchies and encourages exclusivity [10]. Yet, many farms are committed to making healthy food ‘more accessible to everyone’ [13]. Farms have attempted to make CSA more accessible to low-income households by subsidizing the price, eliminating up-front payments, and offering flexible payment plans. This model attempts to reduce some of the barriers to participating in CSA and is often referred to as cost-offset CSA.

Cost-offset CSA has been shown to improve food security and increase FV consumption among participants [11,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21]. The extent to which participants engage in the cost-offset CSA may influence its impact. In a randomized controlled trial, the results revealed a dose–response relationship between the frequency of CSA pick-up and both adult FV intake and improved household food security. For example, for every additional week that households picked up their share, the daily FV intake increased by almost 1/8 cup among adults [20]. Additionally, households that picked up their share for 21 weeks (75th percentile) were 3.73 times as likely to be food secure as households that picked up for only 7 weeks (25th percentile) [20]. This finding is particularly important because levels of engagement in cost-offset CSA vary. For example, CSA share pick-up rates vary from 33% [22] to 86% [23] of weeks across studies and from 33–89% of weeks across locations within a single study [24]. Furthermore, reported drop-out rates can approach half before the end of the first season [17,22,25,26].

Cost-offset CSA has the potential to improve food security and nutrition, but low participation may jeopardize the potential impact of this nutrition intervention. A better understanding of the factors associated with CSA participation among low-income households is needed. To our knowledge, this is the first review article to synthesize the evidence of the factors that support and hinder participation in cost-offset CSA among low-income households. The goal of this research was to (1) conduct a scoping review to identify evidence of factors associated with participation in CSA among households with low incomes; (2) generate a list of emergent themes and aggregate their supporting evidence; and (3) draw upon these themes to make evidence-based practice recommendations for cost-offset CSA and to suggest areas for future research. These evidence-based recommendations may help to facilitate CSA participation by meeting the needs and preferences of low-income households (which may in turn support higher pick-up rates and reduced drop-out rates), thereby increasing the potential of CSA to improve food security and nutrition among residents of low-income households.

2. Methods

A scoping review methodology was used to examine the growing body of research on low-income households and CSA. The scoping review framework allowed us to summarize evidence regarding this relatively broad topic, synthesize findings generated by both qualitative and quantitative data and methods, and encompass both the scholarly and grey literature (e.g., reports and theses) [27]. Our methods were guided by the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) guidelines [28].

2.1. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

We included studies that focused on participation in CSA among households with a low income in the United States (with or without a cost offset) and included at least one of three participation measures: (1) enrollment or the reasons for enrollment, (2) engagement such as picking up the share, and (3) indicators of satisfaction. We included only studies that reported the actual experiences or perspectives of adults in low-income households. One study also included the perspectives of children in low-income households, and these data were retained. Additional data from comparison samples (e.g., higher-income comparison households) were included and clearly marked. Evidence regarding outcome measures or CSA effectiveness did not address our aims and was not included. We excluded studies that did not meet these eligibility criteria, specifically, studies that reported on data from outside the United States, reported on measures beyond participation such as outcomes measures or CSA effectiveness, and studies that presented data from the perspective of someone other than a member of a low-income household (e.g., farmers and middle- or high-income CSA members).

2.2. Literature Search

The search strategy used Google Scholar and PubMed to identify journal articles, reports, and theses that used the following relevant search terms in the title: (“farm share” OR “food system” OR “food movement” OR “CSA” OR “CSAs” OR “community supported agriculture” OR “community-supported agriculture” OR “farm to family”) AND (“Income” OR “subsidized” OR “sociodemographic” OR “underresourced” OR “underprivileged” OR “SNAP” OR “food-insecure” OR “access”). Publication dates from 1 January 2000 through 28 July 2023 (the date of the last search) were included. Titles and abstracts were screened and advanced to the full-text review if they appeared to meet the inclusion criteria. The full-text review verified that the reference reported on data from the U.S., included a sample of low-income individuals or households, reported data from the perspective of adults with a low income, and included data on one or more of the three participation measures of interest (enrollment, engagement, and satisfaction). References cited by all articles that met the inclusion criteria after the full-text review were also screened for possible inclusion. If the title and/or abstract met the screening criteria, a full-text review of these additional articles was performed. Selected references that met the criteria above were added to the review.

2.3. Extraction

The following information was extracted from each eligible article: full citation, location/setting, study period, intervention design, study design for the reported measures of participation, sample size and type, and measures of participation assessed. We also extracted two types of evidence. First, descriptions of the characteristics and motivations of those who enrolled, the preferred share size and contents, and favorable farm operations and supports were extracted. These descriptions included both quantitative data (i.e., percentages reported or observed) and qualitative information (i.e., usual perceptions of interviewees or focus group participants). When present, extracted quantitative data were contextualized by data for the local setting (e.g., population rates). Second, we extracted data on associations between CSA enrollment, engagement or satisfaction and participant characteristics, share contents and frequency, or farm operations and supports. Associations were extracted only if they reported a bivariate test for association at a 95% confidence level or higher. All findings were extracted and placed into an Excel database.

2.4. Quality Assessment

Studies were evaluated according to level of design as follows: (1) randomized controlled trials (RCTs), (2) quasi-experiments with non-randomized comparison groups, and (3) observational, qualitative, and other non-experimental approaches. Opinions (level 4 studies) were not included in this review, nor was anecdotal evidence reported in the context of other study designs. Studies were also evaluated with respect to selection bias by noting (1) small samples (n < 30), (2) skewed sample selection (e.g., including the replacement of intervention drop-outs), (3) low response rates, and (4) multiple studies reporting on the same sample. In addition, we noted studies that reported data on perceptions of a hypothetical CSA among individuals largely unfamiliar with the CSA model and therefore particularly prone to bias.

2.5. Analysis

We conducted a descriptive analysis of the findings extracted from the selected articles. The first two authors separately reviewed each article and independently extracted the findings; any discrepancies in extraction were discussed until a consensus was reached. The third author grouped findings according to factors and by the measure of participation within factors, and then developed a list of initial themes. Initial themes were discussed amongst all three authors and themes were refined. Themes with three or more supporting studies were presented in tables and discussed below. Within each theme and participation measure, evidence was presented according to the sample type: first, interviewees responding to a description of a hypothetical CSA; second, low-income CSA members; and third, cost-offset CSA participants.

3. Results

3.1. Study Selection

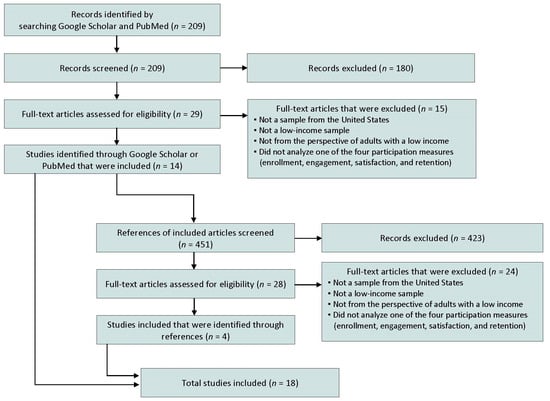

Two hundred nine studies were identified through the search strategy, all were screened, and 29 met the criteria for full-text review (see Figure 1). After the full-text review, 14 studies met all inclusion criteria and were retained [11,17,23,24,25,26,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36]. The references of these fourteen sources were screened (n = 451), 28 met the criteria for the full-text review, and four met the inclusion criteria [16,22,37,38] and were retained, for a total of 18 sources (see Appendix A).

Figure 1.

Selection of sources of evidence.

3.2. Study Characteristics

Multiple studies included samples from states in the Northeast [16,17,22,23,24,29,31,33,34,36,37] and west [23,24,25,26,30,31,33,34,36] regions of the United States, but only two from the Midwest [37,38] and none from the Southwest. North Carolina was the only state contributing samples from the Southeast, and multiple studies were conducted in that state [11,23,24,31,32,33,34,35,36]. Most studies (15 of 18) presented evidence collected since 2010 [16,17,22,23,24,25,26,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36].

All findings extracted were observational or qualitative (level 3) in three broad categories: (1) surveys of low-income CSA members [16,30,37], (2) qualitative research that assessed interest in a hypothetical CSA [17,29,31,32,34], and (3) cost-offset CSA intervention studies [11,17,22,23,24,25,26,33,35,36,38]. Five studies provided a comparison group against which to compare CSA participants from low-income households: higher-income CSA members or those who paid the full price [30,37,38], cost-offset CSA applicants who did not enroll [16,23], or a comparison sample of low-income households that did not apply or enroll [16]. Five studies used qualitative methods with cost-offset CSA participants to assess satisfaction [11,22,25,33,36]. Four papers reported different analyses from one sample of participants in a cost-offset CSA intervention [23,24,33,36], but no duplicate findings were extracted.

Among the twelve studies that examined a cost-offset intervention, three interventions (six studies) provided price subsidies of 50% [16,22,23,24,33,36], three offered a 100% offset (free) [11,35,38], and three offered a subsidy somewhere in between [17,25,26]. Among interventions that were not free, average prices ranged from $5/week [17,22,25] to $13/week [23,24,33,36] and almost all accepted Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) benefits as payment [17,22,23,24,25,26,33,36]. Most cost-offset CSA interventions also offered supports such as printed information and recipes [11,22,23,24,25,26,33,35,36] and/or FV education/preparation classes [17,23,24,25,26,33,35,36]. One cost-offset CSA intervention (four studies) provided kitchen tools [23,24,33,36] and one offered delivery [11].

3.3. Characteristics of CSA Participants from Low-Income Households

Five studies provided evidence that women may be more likely to enroll in cost-offset CSA (see Table 1). Two cost-offset CSA interventions used selection criteria that excluded men [32,35], but five others enrolled predominantly women (85–100%) without such restrictions [16,23,25,26,38]. One of these studies also reported that eligible mothers were more likely to enroll than eligible fathers (97.4% vs. 87.2%), despite both indicating interest in cost-offset CSA by completing a screening questionnaire [23].

Table 1.

Characteristics of Community Supported Agriculture (CSA) participants from low-income households.

Four studies suggested that college graduates may be more likely to enroll or engage in CSA. Three studies reported that low-income CSA members were more often college-educated than the state overall (82% vs. 31%) [30] and the county overall (62% vs. 28%) [38], and that cost-offset CSA participants were more often college-educated than a low-income comparison group (67% vs. 22%) [16], suggesting that a college education may facilitate enrollment. Another study reported that cost-offset CSA participants with a college education were more engaged; that is, they picked up shares a greater percentage of weeks than their counterparts with less education (82.6 vs. 57.8%) [24].

Three studies provided evidence that a lack of familiarity with CSA may hinder enrollment: most adults in low-income households were unfamiliar with CSA when it was described to them [29,31,32]. When a hypothetical CSA was described, some adults in low-income households perceived it as beneficial yet remained cautious about enrolling [31,32]. Three studies suggested that high self-efficacy for food preparation may support enrollment and engagement. In two studies, applicants to a cost-offset CSA had high self-efficacy for food preparation before the intervention began [16,25], and one other study reported that most cost-offset CSA participants knew how to prepare the FVs in their shares [11].

3.4. CSA Share Features Favorable to Low-Income Households

In general, CSA produce was perceived as high quality, which may facilitate enrollment and satisfaction. Ten studies provided evidence that adults in low-income households perceive FVs from CSA farms to be of high quality, whether or not they ever participated in CSA (see Table 2) [11,17,22,25,26,30,31,34,35,37]. Two studies reported that adults would be motivated to enroll in a hypothetical CSA because the FVs were high quality [31,34], one study reported that FV quality motivated low-income CSA members to enroll [37], and seven studies reported that low-income CSA members and cost-offset CSA participants [11,17,22,25,26,30,35] were satisfied with the quality of produce. Adults described FVs from CSA as fresh [11,17,22,25,31], better tasting [11,35], and free of pesticides [22,37].

Table 2.

Community Supported Agriculture (CSA) features favorable to low-income households.

Six studies provided evidence that suggested CSA shares that include a variety of FVs may support enrollment and satisfaction. Two studies reported that adults and children in low-income households want a variety of FVs in a hypothetical CSA [31,34]. Four studies reported that cost-offset CSA participants were satisfied with the variety of FVs they received [11,22,35,36], and appreciated receiving FVs they perceived as too expensive for them to purchase at the grocery store [22,35]. One study also reported that some cost-offset CSA participants expressed frustration that their shares lacked variety [36]. The most commonly preferred FVs were green beans, lettuce, and tomatoes [11,31], as well as broccoli, carrots, corn, onions, peas, peppers, and potatoes [31]. In one study, more than half of adults from low-income households requested broccoli, carrots, cucumbers, green beans, peppers, potatoes, and tomatoes in a hypothetical CSA share [31]. Three studies also found that cost-offset CSA participants wanted more fruit in their share [11,17,22].

Three studies reported mixed reactions to unfamiliar produce items: some cost-offset CSA participants enjoyed the challenge of using new FVs [22,36] and others left unfamiliar items uneaten [11,36].

Four studies provided that a choice of FVs in CSA shares may support enrollment and satisfaction. When interviewed about a hypothetical CSA, adults from low-income households described wanting to choose the FVs in their share [31,32], and indicated that not being able to choose would be a barrier to enrollment [29,31,32]. Cost-offset CSA participants were more satisfied when they were able to choose their own FVs and perceived the share to have greater value when they selected the FVs, and those who were not offered self-selection requested it [36].

Eight studies provided evidence that a choice of share sizes may support engagement and satisfaction by meeting diverse household needs. Six studies reported that cost-offset CSA participants received an adequate or more than adequate quantity of FVs in their CSA shares [11,17,23,25,26,36]. Three studies reported that some cost-offset CSA participants thought the share was too small [11,17,22]. In three cost-offset CSA interventions (six studies), participants were offered multiple share sizes [11,22,23,24,33,36]. In one study, participants were offered two shares sizes and requested a third size because the full share was too large but the half share was too small [22]. When participants were offered a choice of share sizes, they picked up more shares than when it was not offered (76.8% vs. 57.7% of weeks) [24].

3.5. Cost-Offset CSA Operational Practices Favorable to Low-Income Households

Eight studies provided evidence that a low price may motivate enrollment in cost-offset CSA [17,30,31,32,34,36,37,38] (see Table 3). When interviewed about a hypothetical CSA, more than half of adults in low-income households reported that a low price was important for enrollment [31], and some perceived that they would be unlikely to join due to the high cost [32,34]. As the price increased, interest in CSA seemed to wane. One study reported that 67% of adults were interested in the hypothetical CSA at a reduced price but only 18% were interested at full price [17]. Among CSA members from low-income households, affordability was a more important motivation to join than among members from higher-income households [30]. Similarly, among cost-offset participants, receiving low-cost produce was what attracted many participants in the first place [36]. Five studies reported that cost-offset CSA participants were satisfied with the CSA’s ‘value’ (generally described as price and quality) [11,17,22,30,36].

Table 3.

Community Supported Agriculture (CSA) operational practices favorable to low-income households.

Three studies suggested that acceptance of SNAP benefits may support CSA enrollment and engagement. When asked about a hypothetical CSA, the majority of adults from low-income households were interested in paying with SNAP benefits [17,29,31]. In one study, most cost-offset CSA participants did use their SNAP benefits to cover payments for their CSA shares [17].

Seven studies provided evidence that CSA participants from low-income households desired convenient pick-up locations [17,30,31,33,34,35,36], which they defined as nearby or on existing travel routes. When asked about a hypothetical CSA, 66% of adults from low-income households reported that a convenient pick-up location would be a facilitator to enrollment [31], and most were willing to travel 15 min or less to get their CSA shares [34]. CSA members from low-income households placed greater importance on a nearby pick-up location than their higher-income counterparts [30]. Similarly, cost-offset CSA participants wanted pick-up locations near home [36] or near daily activities like transporting children [33], and faced challenges with pick-up locations that were further away [35] or were an ‘extra errand’ [36]. One study reported that pick-up rates were higher among households whose children remained enrolled in Head Start (the pick-up location) than among those whose children withdrew and therefore they had to make a special trip to pick-up the CSA share (81% vs. 57%) [17].

Three studies provided evidence that delivery of CSA shares was desired by adults in low-income households. When asked about a hypothetical CSA, many adults requested that their CSA shares be delivered in order to save scarce time [31]. When offered delivery, most cost-offset CSA participants selected it (68%) [11], and among participants not offered delivery, some requested it [33].

Seven studies reported mixed results regarding organization, communication, and a sense of belonging among CSA participants from low-income households. Two studies reported that some cost-offset CSA participants were frustrated by disorganization, such as poorly organized pick-up locations [22,36], confusion regarding share contents [36], and payments systems that seemed confusing or inaccurate [22,36]. CSA members from low-income households valued ease of communication with the farmers more than their higher-income counterparts [30]. Cost-offset CSA participants also reported that they were satisfied with clear labelling at pick-up locations where FVs were self-selected [36], and appreciated instrumental supports like reminders [25,36] and newsletters [36]. Three studies described positively the context or environment in which the CSA operated. Most cost-offset CSA participants rated the environment as ‘excellent’ (85%) [26], and described a sense of ‘belonging’ [25], support from other cost-offset CSA participants [36], and farmers who ‘trusted them,’ and were ‘accommodating’ [36]. In contrast, CSA members from low-income households were somewhat less likely to feel a part of the CSA community than their higher-income counterparts (46% vs. 63%) [38]. Geospatial data showed that cost-offset CSA participants who travelled to pick-up locations geographically further from their homes also spanned a greater socio-economic distance from their own neighborhoods [33].

Five studies provided evidence that educational supports may facilitate enrollment and satisfaction with cost-offset CSA. When asked about a hypothetical CSA, one study reported that adults from low-income households described needing both ‘new and healthy recipes’, as well as ‘hands-on’ cooking instruction [29]. Three studies reported that cost-offset CSA participants found printed materials like recipes and newsletters [22,26], active demonstrations [26], and informal advice from the farmers [36] all to be helpful educational supports. Some cost-offset CSA participants wanted more, including how to store highly perishable FVs [11,36] and how to preserve FVs with canning and freezing [22,36].

4. Discussion

The descriptive analysis identified 21 themes supported by correlational evidence from three or more studies of participation in CSA among low-income households. Together these findings support 13 recommendations for evidence-based practices that may support enrollment and engagement in cost-offset CSA by low-income households. We also identified five areas for future research.

4.1. Evidence-Based Recommendation for Cost-Offset CSA

- 1.

- Focus on recruiting women: CSA participants from low-income households (with or without a cost offset) were predominantly women (85–100%) [16,23,25,26,38]. This is consistent with other data that suggest women assume the primary responsibility for meal planning, preparation, and shopping [39,40,41]. Given this gendered context, recruitment efforts that focus on recruiting women into cost-offset CSA may be most successful.

- 2.

- Build awareness around CSA: Most adults in low-income households were unfamiliar with CSA (71–87%) [31,32] which may hinder enrollment. Teaching people about the CSA model may be an important part of recruiting new members from low-income households but may be too time consuming for farms to integrate into daily public interactions. Little is known about how best to educate the public about how CSA works. Galt et al. (2017) reported that when deciding whether to enroll in CSA, low-income households were more likely than higher-income households to use websites (21 vs. 12%) and social media (16 vs. 4%) as important sources of information [30]. This suggests that online resources to address the lack of familiarity with the CSA model may be effective and time saving.

- 3.

- Amplify message that CSA produce is high-quality: Ten of eighteen reviewed studies suggest that there is a widespread belief that CSA produce is high quality among both CSA participants and adults with no CSA experience [11,17,22,25,26,30,31,34,35,37]. Fresh, quality, and organic FVs were motivators to join a CSA [31,34,37], and fresh, quality, organic FVs and taste were important to satisfaction among CSA members [11,17,22,25,26,30,35]. However, it is important to note that two studies reported dissatisfaction with the quality of produce [11,36], including the presence of bugs, mold, and quick spoilage [36]. Recruitment efforts could amplify positive perceptions of CSA quality while also being transparent about the variable aesthetics of farm produce [42] relative to homogenous grocery store produce [43] and creating realistic expectations.

- 4.

- Include a variety of FVs and/or 5. Offer self-selection of FVs: The reviewed studies suggest that a variety of FVs and more fruit are desired in CSA shares. Three items were reported in multiple studies as preferred by adults and children in low-income households: potatoes (43–51%), carrots (50–75%), and tomatoes (35–60%) [31]. Three studies described cost-offset CSA participants as receiving less fruit than they expected or desiring more fruit than they received [11,17,22]. Food preferences vary and may be influenced by social and cultural norms, making it challenging to select FVs enjoyed by all [44,45]. Eight of the reviewed studies had predominantly white, non-Hispanic samples [16,23,24,25,30,31,34,36], and race and ethnicity were not reported in six other studies [11,32,33,35,37,38], providing little information about participants’ cultural contexts. Farms often choose what goes into CSA shares, but sometimes they offer members choice about share contents [46]. The reviewed studies support the idea that the self-selection of share contents (sometimes called a ‘market style’ CSA) may facilitate enrollment and satisfaction [29,31,32,36]. If this is not possible, offering shares that have variety [11,22,31,34,35,36], including some specialty items that are perceived as otherwise unaffordable [22,35], and adding more fruit [11,17,22] may also support CSA participation by low-income households.

- 6.

- Offer multiple share sizes: We found ample evidence that FV quantity in CSA shares was usually adequate [11,17,23,25,26,36]. Cost-offset CSA participants described the size as ‘just right’ and 82–93% reported using all the FVs most weeks [17,23]. There was some evidence that the quantity was insufficient relative to the expectations or family size [11,17,22], and limited evidence that shares were too large. Cost-offset CSA participants frequently had a choice of two share sizes, and some wanted a third ‘in-between’ size. Moreover, importantly, when cost-offset CSA participants were offered a choice of share sizes, they picked up their shares on more weeks (77 vs. 58%) [24]. Farms can support CSA enrollment and engagement by offering multiple share sizes to meet diverse needs.

- 7.

- Keep prices low: The reviewed studies provide ample evidence that low prices, affordability, and ‘good value’ are important to low-income households. Four studies reported that a low cost or affordability would be motivators to join a hypothetical CSA [17,31,32,34], and four more reported they did motivate participation among CSA members [30,36,37,38]. Five studies described satisfaction with the ‘value’ of CSA shares [11,17,22,30,36], and two quantified this satisfaction as nearly universal (91–93% of CSA members) [11,17]. However, meeting general value expectations may be challenging for farms. The price of CSA varies based on factors such as size and duration. In the Northeast (for example), the CSA season typically runs for 22 weeks with an average cost of $400–$500 for a standard share (or about $20/week) [47]. Two prior studies suggests that low-income consumers are willing to pay approximately $10/week for a small CSA share and $15/week for large share [34,35]. All reviewed studies that tested a cost-offset CSA intervention included a price reduction of 50% or more. The estimated willingness to pay $10–15/week supports the idea that cost offsets of at least 25% (and likely 50%) may be needed for low-income households to participate in a CSA (given average price of $20/week). The cost offsets or subsidizes may be obtained through member donations, fundraising, or grants [13]. Community organizations may be able to ease the burden on farms by securing and providing the subsidies needed to keep the price within this threshold [48,49].

- 8.

- Accept SNAP benefits: Most cost-offset CSA programs accepted SNAP as weekly payment for CSA shares, and potential participants wanted this option (51–59%) [16,17,29]; many cost-offset CSA members used SNAP as payment (67%) [17]. This is particularly important given that many low-income households participate in SNAP. Data from the USDA show that over 80% of people eligible for SNAP participate in the program [50]. Farmers’ markets are a common location for CSA pick-up [51]; however, less than half of the nearly 7000 farmers’ markets are authorized to accept SNAP benefits [52]. In order to serve low-income households, farms may need to become authorized to accept SNAP payments directly or work with a community partner who can process SNAP payments [49].

- 9.

- Offer convenient pick-up locations and/or 10. Provide delivery: We found substantial evidence that CSA members desired convenient CSA pick-up. Low-income households preferred pick-up locations that were close to home [30,34,35,36] and/or near places that participants were already travelling (e.g., school and childcare) [17,31,33,36]. One study reported that a short distance to pick-up was more important to CSA members from low-income households than it was for their higher-income counterparts [30]. Three studies reported that delivery was requested by cost-offset CSA participants and potential participants [11,31,33], and that participants used the service when offered [11,33]. Constraints on time and physical mobility may contribute to a need for convenience. Low-income households are time poor, as well as have limited financial resources [53]. Additionally, nearly one-quarter of disabled people live in poverty [54]. Participation by low-income households may be supported by locating pick-up sites close to affordable housing and/or services such as health centers and Head Start programs and partnering with delivery services. Distribution can be time-consuming for farms, and in response to this, community groups and neighborhood volunteers have sometimes stepped in to assist with CSA distribution and delivery [49].

- 11.

- Prioritize clear communication: CSA participants from low-income households valued clear communication, including labelling of FVs, newsletters, and reminders, and were frustrated by disorganized pick-up and payment systems. CSA members from households with a low income placed greater importance on ease of communication with CSA staff/farmer than their higher-income counterparts [30]. CSA often uses a subscription model that requires up-front payment [46], whereas cost-offset CSA eliminates up-front payments and offers flexible payment plans. This requires tracking and managing multiple payments, which can intensify the need for clear and consistent communication, particularly regarding payment. Clear communication systems may be particularly important to retain CSA members from low-income households who need to make multiple payments.

- 12.

- Foster an environment of belonging and trust: Some CSA participants from low-income households described a supportive and trusting environment that sometimes included socializing and instrumental support [25,26,36]. However, cost-offset CSA participants were somewhat less likely to feel a part of the CSA community compared to their higher-income counterparts [38]. One study reported that cost-offset CSA participants who travel further to pick-up locations enter starkly different socio-demographic contexts [33]. Individuals with a low income often struggle with inadequate social networks and support [55,56]. A positive environment that supports trust, belonging, and socialization may facilitate participation in cost-offset CSA.

- 13.

- Provide educational support: Cost-offset CSA participants appreciated educational support and found it helpful [11,22,26,36]. Three studies suggested specific interest in food storage and preservation [11,23,36]. However, Garner et al. (2021) reported very low attendance when education classes were offered as a separate activity in a cost-offset CSA program [23]. Thus, integrating education into CSA pick-up may be a more feasible mode of education for busy households. When cooking demonstrations and tastings were offered at pick-up, 71% of cost-offset CSA participants rated this component highly [26].

4.2. Opportunities for Future Research

- Investigate why adults with less education do not enroll in CSA: Many low-income CSA participants were college graduates (62–82%) [16,30,38], which is atypical given that only 13% of the low-income adults have a college degree [57]. Future research should investigate why women with less education do not enroll in cost-offset CSA and identify potential adaptations to better meet their needs.

- Investigate ways to develop self-efficacy for food preparation: CSA participants from low-income households had high self-efficacy for food preparation (even before CSA enrollment) [11,16,25]. Future research should explore mechanisms by which self-efficacy for food preparation can be developed prior to or in the context of cost-offset CSA participation.

- Investigate which FV varieties are both preferred by households and profitable for farms: Crop planning is an important component of developing a successful CSA. The profitability of different crops can vary depending on factors such as the labor intensity of growing and harvesting, field space or acreage needed, and the time needed for crop maturation [58]. In addition, little is known about the specific items that CSA members from low-income households prefer, and taste preferences may be highly dependent on local cultures and ethnicities [44,45]. Future research should investigate methods to identify FVs that are preferred by low-income households and also considered profitable for farms within a local area.

- Investigate the association between offering a CSA with FV self-selection and participation: Self-selection of FVs within the CSA share was popular among CSA members from low-income households [29,31,32,36]. To our knowledge, no data are available on how common self-selection of FVs is in CSA operations. Future research should document the prevalence of self-selection mechanisms and test the association with CSA participation among low-income households.

- Investigate CSA engagement at different prices: Among the cost-offset CSA interventions reviewed, subsidies varied from 50% to 100% (free) [11,16,17,22,23,24,25,26,33,35,36,38], and prices among shares that were not free varied from $5 to $13/week [11,17,22,23,24,25,26,33,35,36]. However, participation at different subsidies and price levels was not compared in any study. Future research should compare CSA participation by low-income households at different prices and cost-offset levels.

4.3. Importance of Community Engagement

In a national survey, nearly five hundred CSA managers were asked about their interest in cost-offset programs for low-income households and over two-thirds reported being very interested or possibly interested in this mechanism [49]. Farms with experience implementing a cost-offset CSA report that they believe it is a worthwhile addition to their business model [59]; however, farms that were exploring this mechanism cited additional management and administrative duties as barriers to implementation [13,60].

The recommendations made in this paper have the potential to enhance participation in cost-offset CSA among low-income households, but required changes in finances and operations may mean that some farms struggle to implement a cost-offset CSA program alone. A community-engaged approach to CSA has been advocated for in other studies and might benefit from enacting these recommendations as well [61]. For example, some of the recruitment strategies that we present here may be best led by a community organization or community liaison who already has existing relationships with adults in low-income households and can facilitate building trust with farms [13,48,49]. Furthermore, community organizations have relieved some of the pressure on farms by helping with distribution and delivery, managing flexible payment structures, processing SNAP payments, financing subsidies to keep prices low, and delivering education [48,49].

4.4. Limitations

There are several limitations of this review that deserve to be noted. First, five studies used small samples (n < 30) [11,17,25,29,35], which may not be representative of the population and limit the generalizability of findings. Second, five studies collected data on interest in or willingness to pay for a hypothetical CSA [17,29,31,32,34]. Because many adults in low-income households were completely unfamiliar with CSA [29,31,32], the validity of these results may be limited. Third, four studies used sampling techniques that introduced potential bias. Three of these studies replaced CSA participants who dropped out [11,25,26] (two had dropout rates approaching half [25,26]), which may bias estimates of engagement upwards. Another study conducted post-intervention focus groups to which they only invited the participants who had picked-up the most CSA shares [22]. Finally, four studies reported different data but from the same sample of participants in a cost-offset CSA [23,24,33,36], which therefore over-represents the perspectives of these participants.

5. Conclusions

This review suggests evidence-based recommendations to support more robust enrollment and engagement in cost-offset CSA by low-income households. For recruitment into CSA, low-income households need to be educated about how CSA works and amplify perceptions of high quality FVs. Farms may need to offer low-income households a choice of shares sizes to meet diverse needs, as well as a variety of FVs or the option to self-select share contents. Cost-offsets of at least 25% (and likely 50%) are needed to achieve CSA prices of $10–15/week (which low-income households viewed as affordable), with the option to pay with SNAP benefits. Flexible systems for payment, pick-up (or delivery), clear communication, and a supportive environment all may be needed for CSA to be broadly feasible for and acceptable to low-income households. These recommendations may be challenging for farms, and a community-engaged approach may support their implementation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.L.H.; methodology, K.L.H., C.C. and L.C.V.; formal analysis, K.L.H., C.C. and L.C.V.; investigation, C.C. and L.C.V.; data curation, L.C.V.; writing—original draft preparation, K.L.H. and C.C.; writing—review and editing, K.L.H. and L.C.V.; visualization, K.L.H. and L.C.V.; supervision, K.L.H.; project administration, K.L.H.; funding acquisition, K.L.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the intramural research program of the U.S. Department of Agriculture, National Institute of Food and Agriculture, Hatch research award #7005177. The funder was not involved in the study design; collection, analysis and interpretation of data; the writing of the report; nor the decision to submit the article for publication. The findings and conclusions in this preliminary publication have not been formally disseminated by the U.S. Department of Agriculture and should not be construed to represent any agency determination or policy.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A. Studies included in the scoping review and their characteristics

| Source | Location/Setting, Study Period, Intervention | Study Design | Sample(s) | Measures of Participation Assessed |

| Abbott 2014, “Evaluation of the Food Bank of Delaware Community Supported Agriculture (CSA) Program” [22] | Wilmington, DE; 2013 Intervention

| Qualitative analysis: Focus groups with cost-offset CSA participants | Participant sample (n = 208) Eligibility criteria:

Focus group sample (n = 10) Eligibility criteria:

| Satisfaction

Retention

|

| Andreatta et al., 2008, “Lessons learned from advocating CSAs for low-income and food insecure households” [11] | Piedmont region of North Carolina; 2002–2003 Intervention

| Observational: Summary statistics and qualitative analysis of pre- and post-season interviews with participants | Participant sample (n = 22) Eligibility criteria:

| Enrollment

Satisfaction

|

| Brehm and Eisenhauer 2008, “Motivations for Participating in Community-Supported Agriculture and Their Relationship with Community Attachment and Social Capital” [37] | Central Illinois and New Hampshire, 2006 CSA Member survey

| Observational: Cross-sectional analysis of participant surveys, compared across household incomes | Participant sample (n = 225)

| Enrollment

|

| Cotter et al., 2017, “Low-income adults’ perceptions of farmers’ markets and community supported agriculture programmes” [29] | Three affordable housing communities in Washington, DC; 2015–2016 Hypothetical CSA | Qualitative analysis: Focus groups | Multi-lingual focus groups (n = 28) Eligibility criteria:

| Enrollment

|

| Galt et al., 2017, “What difference does income make for Community SupportedAgriculture (CSA) members in California: Comparinglower-income and higher-income households” [30] | CA statewide, 2014–2015 CSA member survey

| Observational: Summary of cross-sectional survey data for low-income households (and compared to higher-income households) | CSA member sample (n = 1049) Eligibility criteria:

| Enrollment

Satisfaction

|

| Garner et al., 2021, “Making community-supported agriculture accessible to low-income families: findings from the Farm Fresh Foods for Healthy Kids (F3HK) process evaluation” [23] | Rural and micropolitan communities in 4 U.S. states (NY, NC, VT, and WA); 2016–2017 Intervention

| Observational: Cross-sectional analysis of

| Eligibility requirements:

Applicant sample (n = 548) Intervention sample (n = 115) | Enrollment

Engagement

|

| Hanson et al., 2019, “Fruit and Vegetable Preferences and Practices may Hinder Participation in Community Supported Agriculture among Low-income Rural Families” [31] | Rural and micropolitan communities in 4 states (NY, NC, VT, and WA), 2015 Hypothetical CSA | Observational: Summary of recorded FV preferences Qualitative analysis: Interviews | Adult Sample (n = 41, ~10 from each state) Eligibility criteria:

Child Sample (n = 20, ~5 from each state) Eligibility criteria:

| Enrollment

|

| Hanson et al., 2019, “Knowledge, Attitudes, Beliefs and Behaviors Regarding Fruits and Vegetables among Cost-offset Community Supported Agriculture Applicants, Purchasers, and a Comparison Sample” [16] | VT statewide and comparison group from all New England states (MA, CT, RI, VT, NH, and ME); August 2017 Cost-offset CSA member survey

| Observational: Cross-sectional comparison of online survey data from applicants and a non-applicant comparison group | Overall eligibility requirements:

Applicant sample (n = 64) Applicant eligibility requirements:

Comparison sample (n = 105) Comparison eligibility requirements:

| Enrollment

|

| Hanson et al., 2022, “Participation in Cost-offset Community Supported Agriculture by Low-income Households in the U.S. is Associated with Community Characteristics and Operational Practices” [24] | Rural and micropolitan communities in 4 U.S. states (NY, NC, VT, and WA); 2016–2017 Intervention

| Observational: Examined differences in shares picked up (recorded in pick-up logs) by community and participant characteristics and CSA operational practices | Participant sample (n = 137) Eligibility requirements:

| Engagement

|

| Hinrichs and Kremer 2002, “Social inclusion in a Midwest local food system project” [38] | Midwest, 1997–1998 Intervention

| Observational:

| CSA participant sample (n = 41)

| Enrollment

Satisfaction

|

| Hoffman et al., 2012, “Farm to Family: Increasing Access to Affordable Fruits and Vegetables Among Urban Head Start Families” [17] | Four Head Start centers in Boston, MA; 2010–2011 Hypothetical CSA + Intervention

| Observational:

| Overall eligibility criteria:

Pre-intervention Survey Sample (n = 139) Participant Sample (n = 14) Participant eligibility criteria:

| Enrollment

|

| Izumi et al., 2018, “Feasibility of Using a Community-Supported Agriculture Program to Increase Access to and Intake of Vegetables among Federally Qualified Health Center Patients” [25] | Federally qualified health center (FQHC), Portland, OR; 2015 Intervention

| Observational: Cross-sectional summary of pre- and post-intervention survey data Qualitative analysis: Post-intervention focus groups | Participant survey sample (n = 9) Eligibility criteria

Participant focus group sample (n = 15) | Enrollment

Satisfaction

|

| Izumi et al., 2020, “CSA Partnerships for Health: outcome evaluation results from a subsidized community-supported agriculture program to connect safety-net clinic patients with farms to improve dietary behaviors, food security, and overall health” [26] | Federally qualified health center (FQHC), Portland, OR; 2017 Intervention

| Observational: Summary of pre- and post-intervention telephone and paper surveys | Participant sample (n = 48) Eligibility criteria

| Satisfaction

Retention

|

| Martin. et al., 2019, “Low-income mothers and the alternative food movement: An intersectional approach” [32] | 3 North Carolina counties (1 urban and 2 rural); 2014–2015 Hypothetical CSA | Qualitative analysis: Semi-structured interviews about a hypothetical CSA | Low-income sample (n = 83) Eligibility criteria:

| Enrollment

|

| McGuirt et al., 2018, “A Modified Choice Experiment to Examine Willingness to Participate in a Community Supported Agriculture (CSA) Program among Low-income Parents” [34] | Rural and micropolitan communities in 4 U.S. states (NY, NC, VT, and WA); 2015 Hypothetical CSA | Observational: Summary of a modified choice experiment about a hypothetical CSA (travel distance, share size, share frequency, and price) conducted during interviews Qualitative analysis of interview comments | Sample (n = 42, ~10 from each state) Eligibility criteria:

| Enrollment

|

| McGuirt et al., 2019, “A mixed-methods examination of the geospatial and sociodemographic context of a direct-to-consumer food system innovation” [33] | Rural and micropolitan communities in 4 U.S. states (NY, NC, VT, and WA); 2016–2017 Intervention

| Observational: Geospatial analysis of participants’ homes, CSA farms, and pick-up locations Qualitative analysis: Focus groups with participants | Geospatial data

Participant sample (n = 53) Eligibility criteria:

| Satisfaction

|

| Quandt et al., 2013, “Feasibility of using a Community-Supported Agriculture Program to improve fruit and vegetable inventories and consumption in an underresourced urban community” [35] | Forsyth County, NC; 2012 Intervention

| Observational: Descriptive analysis of post-intervention telephone interviews | Participant sample (n = 25) Eligibility criteria:

| Satisfaction

Retention

|

| White et al., 2018, “The perceived influence of cost-offset community-supported agriculture on food access among low-income families” [36] | Rural and micropolitan communities in 4 U.S. states (NY, NC, VT, and WA); 2016–2017 Intervention

| Qualitative analysis: Post-intervention focus groups | Participant sample (n = 53) Eligibility criteria:

| Satisfaction

|

References

- Slavin, J.L.; Lloyd, B. Health benefits of fruits and vegetables. Adv. Nutr. 2012, 3, 506–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Snetselaar, L.G.; de Jesus, J.M.; DeSilva, D.M.; Stoody, E.E. Dietary guidelines for Americans, 2020–2025: Understanding the scientific process, guidelines, and key recommendations. Nutr. Today 2021, 56, 287–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruening, M.; MacLehose, R.; Loth, K.; Story, M. Neumark-Sztainer D: Feeding a family in a recession: Food insecurity among Minnesota parents. Am. J. Public Health 2012, 102, 520–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Champagne, C.M.; Casey, P.H.; Connell, C.L.; Stuff, J.E.; Gossett, J.M.; Harsha, D.W.; McCabe-Sellers, B.; Robbins, J.M.; Simpson, P.M.; Weber, J.L. Poverty and food intake in rural America: Diet quality is lower in food insecure adults in the Mississippi Delta. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2007, 107, 1886–1894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cristofar, S.P.; Basiotis, P.P. Dietary intakes and selected characteristics of women ages 19–50 years and their children ages 1–5 years by reported perception of food sufficiency. J. Nutr. Educ. 1992, 24, 53–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixon, L.B.; Winkleby, M.A.; Radimer, K.L. Dietary intakes and serum nutrients differ between adults from food-insufficient and food-sufficient families: Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1988–1994. J. Nutr. 2001, 131, 1232–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grimm, K.A.; Foltz, J.L.; Blanck, H.M.; Scanlon, K.S. Household income disparities in fruit and vegetable consumption by state and territory: Results of the 2009 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2012, 112, 2014–2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kendall, A.; Olson, C.M.; Frongillo, E.A., Jr. Relationship of hunger and food insecurity to food availability and consumption. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 1996, 96, 1019–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.H. Adults meeting fruit and vegetable intake recommendations—United States, 2019. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2022, 71, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonfert, B. ‘What we’d like is a CSA in every town.’Scaling community supported agriculture across the UK. J. Rural Stud. 2022, 94, 499–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreatta, S.; Rhyne, M.; Dery, N. Lessons learned from advocating CSAs for low-income and food insecure households. J. Rural Soc. Sci. (Former. South. Rural Sociol.) 2008, 23, 6. [Google Scholar]

- Guthman, J.; Morris, A.W.; Allen, P. Squaring farm security and food security in two types of alternative food institutions. Rural Sociol. 2006, 71, 662–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitts, S.B.J.; Volpe, L.C.; Sitaker, M.; Belarmino, E.H.; Sealey, A.; Wang, W.; Becot, F.; McGuirt, J.T.; Ammerman, A.S.; Hanson, K.L. Offsetting the cost of community-supported agriculture (CSA) for low-income families: Perceptions and experiences of CSA farmers and members. Renew. Agric. Food Syst. 2022, 37, 206–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agboola, F. Implications of Community Supported Agriculture as Alternative Food Networks; Loma Linda University: Linda Roma, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Berkowitz, S.A.; O’Neill, J.; Sayer, E.; Shahid, N.N.; Petrie, M.; Schouboe, S.; Saraceno, M.; Bellin, R. Health center–based community-supported agriculture: An RCT. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2019, 57, S55–S64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanson, K.L.; Volpe, L.C.; Kolodinsky, J.; Hwang, G.; Wang, W.; Jilcott Pitts, S.B.; Sitaker, M.; Ammerman, A.S.; Seguin, R.A. Knowledge, attitudes, beliefs and behaviors regarding fruits and vegetables among cost-offset community-supported agriculture (CSA) applicants, purchasers, and a comparison sample. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoffman, J.A.; Agrawal, T.; Wirth, C.; Watts, C.; Adeduntan, G.; Myles, L.; Castaneda-Sceppa, C. Farm to family: Increasing access to affordable fruits and vegetables among urban head start families. J. Hunger Environ. Nutr. 2012, 7, 165–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, D.B.; Beaudoin, S.L.; Beresford, S.A.; LoGerfo, J.P. Increasing fruit and vegetable intake in homebound elders: The Seattle Farmers’ Market nutrition pilot program. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2004, 1, A03. [Google Scholar]

- Kato, Y.; McKinney, L. Bringing food desert residents to an alternative food market: A semi-experimental study of impediments to food access. Agric. Hum. Values 2015, 32, 215–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seguin-Fowler, R.A.; Hanson, K.L.; Jilcott Pitts, S.B.; Kolodinsky, J.; Sitaker, M.; Ammerman, A.S.; Marshall, G.A.; Belarmino, E.H.; Garner, J.A.; Wang, W. Community supported agriculture plus nutrition education improves skills, self-efficacy, and eating behaviors among low-income caregivers but not their children: A randomized controlled trial. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2021, 18, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkins, J.L.; Farrell, T.J.; Rangarajan, A. Linking vegetable preferences, health and local food systems through community-supported agriculture. Public Health Nutr. 2015, 18, 2392–2401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbott, C. Evaluation of the Food Bank of Delaware Community Supported Agriculture Program; University of Delaware: Newark, DE, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Garner, J.A.; Jilcott Pitts, S.B.; Hanson, K.L.; Ammerman, A.S.; Kolodinsky, J.; Sitaker, M.H.; Seguin-Fowler, R.A. Making community-supported agriculture accessible to low-income families: Findings from the Farm Fresh Foods for Healthy Kids process evaluation. Transl. Behav. Med. 2021, 11, 754–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanson, K.L.; Xu, L.; Marshall, G.A.; Sitaker, M.; Jilcott Pitts, S.B.; Kolodinsky, J.; Bennett, A.; Carriker, S.; Smith, D.; Ammerman, A.S.; et al. Participation in Cost-offset Community Supported Agriculture by Low-income Households in the U.S. is Associated with Community Characteristics and Operational Practices. Public Health Nutr. 2022, 25, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Izumi, B.T.; Higgins, C.E.; Baron, A.; Ness, S.J.; Allan, B.; Barth, E.T.; Smith, T.M.; Pranian, K.; Frank, B. Feasibility of using a community-supported agriculture program to increase access to and intake of vegetables among federally qualified health center patients. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2018, 50, 289–296.e281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Izumi, B.T.; Martin, A.; Garvin, T.; Higgins Tejera, C.; Ness, S.; Pranian, K.; Lubowicki, L. CSA Partnerships for Health: Outcome evaluation results from a subsidized community-supported agriculture program to connect safety-net clinic patients with farms to improve dietary behaviors, food security, and overall health. Transl. Behav. Med. 2020, 10, 1277–1285. [Google Scholar]

- Mak, S.; Thomas, A. An Introduction to Scoping Reviews. J. Grad. Med. Educ. 2022, 14, 561–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotter, E.W.; Teixeira, C.; Bontrager, A.; Horton, K.; Soriano, D. Low-income adults’ perceptions of farmers’ markets and community-supported agriculture programmes. Public Health Nutr. 2017, 20, 1452–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galt, R.E.; Bradley, K.; Christensen, L.; Fake, C.; Munden-Dixon, K.; Simpson, N.; Surls, R.; Van Soelen Kim, J. What difference does income make for Community Supported Agriculture (CSA) members in California? Comparing lower-income and higher-income households. Agric. Hum. Values 2017, 34, 435–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanson, K.L.; Garner, J.; Connor, L.M.; Pitts, S.B.J.; McGuirt, J.; Harris, R.; Kolodinsky, J.; Wang, W.; Sitaker, M.; Ammerman, A. Fruit and vegetable preferences and practices may hinder participation in community-supported agriculture among low-income rural families. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2019, 51, 57–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, B.; Mycek, M.K.; Elliott, S.; Bowen, S. Low-income mothers and the alternative food movement: An intersectional approach. In Feminist Food Studies: Intersectional Perspectives; Women’s Press: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2019; pp. 183–204. [Google Scholar]

- McGuirt, J.; Sitaker, M.; Pitts, S.J.; Ammerman, A.; Kolodinsky, J.; Seguin-Fowler, R. A mixed-methods examination of the geospatial and sociodemographic context of a direct-to-consumer food system innovation. J. Agric. Food Syst. Community Dev. 2019, 9, 159–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGuirt, J.T.; Pitts, S.B.J.; Hanson, K.L.; DeMarco, M.; Seguin, R.A.; Kolodinsky, J.; Becot, F.; Ammerman, A.S. A modified choice experiment to examine willingness to participate in a Community Supported Agriculture (CSA) program among low-income parents. Renew. Agric. Food Syst. 2018, 35, 140–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quandt, S.A.; Dupuis, J.; Fish, C.; D’Agostino, R.B., Jr. Feasibility of using a community-supported agriculture program to improve fruit and vegetable inventories and consumption in an underresourced urban community. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2013, 10, E136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, M.J.; Jilcott Pitts, S.B.; McGuirt, J.T.; Hanson, K.L.; Morgan, E.H.; Kolodinsky, J.; Wang, W.; Sitaker, M.; Ammerman, A.S.; Seguin, R.A. The perceived influence of cost-offset community-supported agriculture on food access among low-income families. Public Health Nutr. 2018, 21, 2866–2874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brehm, J.M.; Eisenhauer, B.W. Motivations for participating in community-supported agriculture and their relationship with community attachment and social capital. J. Rural Soc. Sci. 2008, 23, 5. [Google Scholar]

- Hinrichs, C.; Kremer, K.S. Social inclusion in a Midwest local food system project. J. Poverty 2002, 6, 65–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flagg, L.A.; Sen, B.; Kilgore, M.; Locher, J.L. The influence of gender, age, education and household size on meal preparation and food shopping responsibilities. Public Health Nutr. 2014, 17, 2061–2070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larson, N.I.; Story, M.; Eisenberg, M.E.; Neumark-Sztainer, D. Food Preparation and Purchasing Roles among Adolescents: Associations with Sociodemographic Characteristics and Diet Quality. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2006, 106, 211–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mills, S.; White, M.; Brown, H.; Wrieden, W.; Kwasnicka, D.; Halligan, J.; Robalino, S.; Adams, J. Health and social determinants and outcomes of home cooking: A systematic review of observational studies. Appetite 2017, 111, 116–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Villar, C. Engaging Past and Future on a Community Supported Agriculture Farm; The University of Western Ontario: London, ON, Canada, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Cicatiello, C.; Franco, S.; Pancino, B.; Blasi, E.; Falasconi, L. The dark side of retail food waste: Evidences from in-store data. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2017, 125, 273–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruwys, T.; Beyelander, K.E.; Hermans, R.C.J. Social modeling of eating: A review of when and why social influence affects food intake and choice. Appetite 2015, 86, 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ventura, A.K.; Worobey, J. Early influences on the development of food preferences. Curr. Biol. 2013, 23, R401–R408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prial, D. Community Supported Agriculture. In ATTRA Sustainable Agriculture; The National Center for Appropriate Technology: Butte, MT, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Fox, D. CSAs in the Capital Region: How they work. Times Union. 2017. Available online: https://www.timesunion.com/tuplus-features/article/CSAs-in-the-Capital-Region-How-they-work-11004701.php (accessed on 9 February 2024).

- Sitaker, M.; McCall, M.; Wang, W.W.; Vaccaro, M.; Kolodinsky, J.M.; Ammerman, A.; Pitts, S.J.; Hanson, K.; Smith, D.K.; Seguin-Fowler, R.A. Models for cost-offset community supported agriculture (CO-CSA) programs. J. Agric. Food Syst. Community Dev. 2021, 10, 157–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woods, T.; Ernst, M.; Tropp, D. Community Supported Agriculture: New Models for Changing Markets; U.S. Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Marketing Service: Washington, DC, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- SNAP Participation Rates by State, All Eligible People (FY 2019). Available online: https://www.fns.usda.gov/usamap (accessed on 2 February 2024).

- Bruch, M.L.; Ernst, M.D. A Farmer’s Guide to Marketing through Community Supported Agriculture (CSAs); University of Tennessee Extension: Knoxville, TN, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Farmers Markets Accepting SNAP Benefits. Available online: https://www.fns.usda.gov/snap/farmers-markets-accepting-snap-benefits (accessed on 2 February 2024).

- De Graaf, J. Take back Your Time: Fighting Overwork and Time Poverty in America; Berrett-Koehler Publishers: Oakland, CA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Shrider, E.A.; Kollar, M.; Chen, F.; Semega, J. Income and Poverty in the United States: 2020; U.S. Government Publishing Office: Washington, DC, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Lubbers, M.J.; García, H.V.; Castaño, P.E.; Molina, J.L.; Casellas, A.; Rebollo, J.G. Relationships Stretched Thin: Social Support Mobilization in Poverty. Ann. Am. Acad. Political Soc. Sci. 2020, 689, 65–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radey, M.; McWey, L.M. Informal Networks of Low-Income Mothers: Support, Burden, and Change. J. Marriage Fam. 2019, 81, 953–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corporation, L.S. The Justice Gap: The Unmet Civil Legal Needs of Low Income Americans; Slosar Research LLC: Weybridge, VT, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- How to Create a Crop Plan for Your CSA in 5 Steps. Available online: https://howtostartanllc.com/csa/how-to-create-crop-plan (accessed on 23 July 2024).

- Sitaker, M.; McCall, M.; Belarmino, E.; Wang, W.; Kolodinsky, J.; Becot, F.; McGuirt, J.; Ammerman, A.; Pitts, S.J.; Seguin-Fowler, R. Balancing social values with economic realities: Farmer experience with a cost-offset CSA. J. Agric. Food Syst. Community Dev. 2020, 9, 29–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verfuerth, C.; Sanderson Bellamy, A.; Adlerova, B.; Dutton, A. Building relationships back into the food system: Addressing food insecurity and food well-being. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2023, 7, 1218299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, B. Local Food, Local Engagement: Community-Supported Agriculture in Eastern Iowa. Cult. Agric. 2010, 32, 4–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).