Adherence to the Gluten-Free Diet Role as a Mediating and Moderating of the Relationship between Food Insecurity and Health-Related Quality of Life in Adults with Celiac Disease: Cross-Sectional Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design and Participants

2.2. Sample Size

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Adherence to a GFD

2.5. Psychometric Analysis of the Adherence to a GFD Questionnaire

2.6. Household Food and Access Insecurity Scale (HFAIS)

2.7. Health-Related Quality of Life (HRQoL)

2.8. Ethical Approval

2.9. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Participants Characteristics

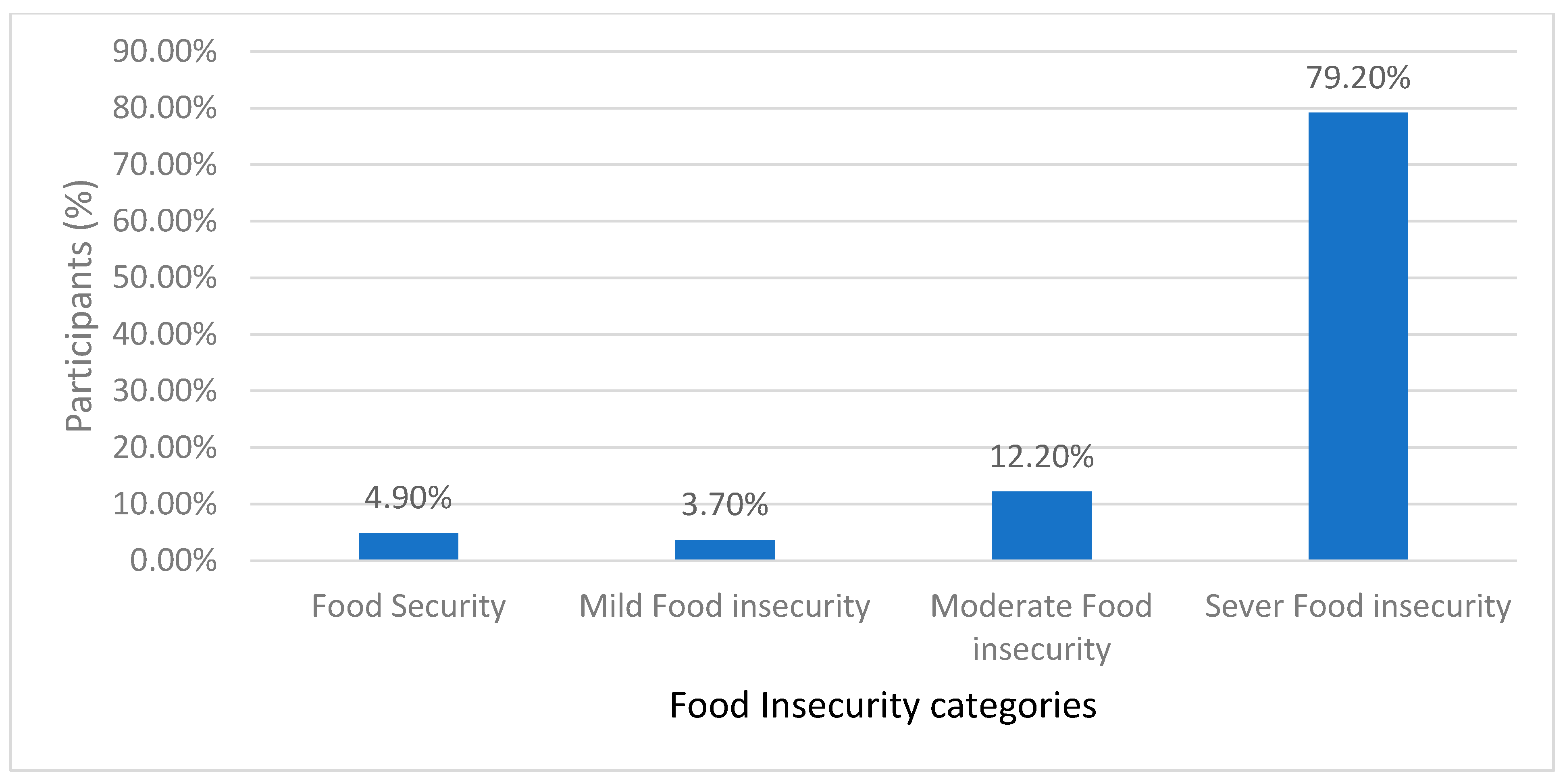

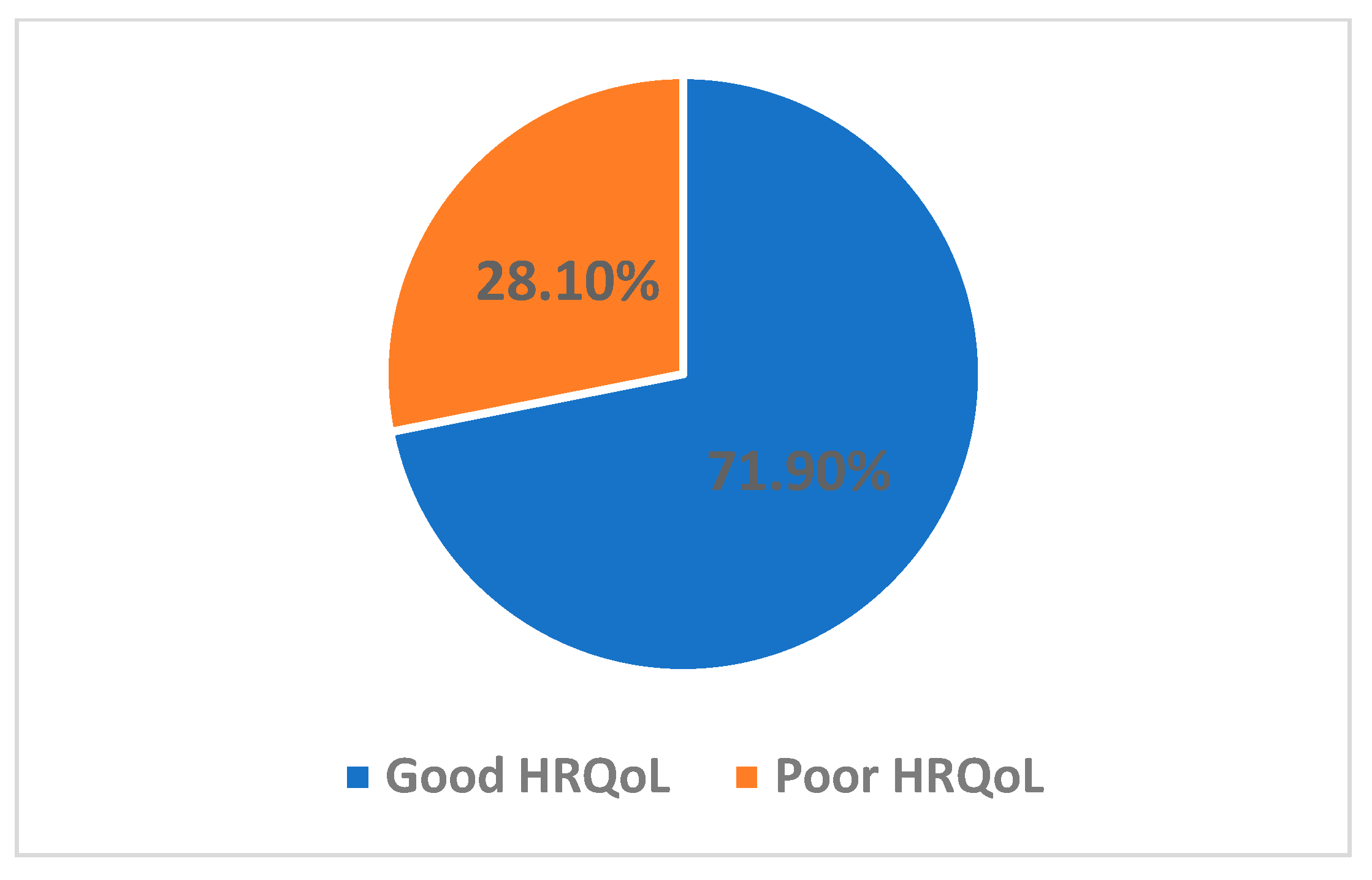

3.2. Exploring FI Patterns, GFD Adherence, and Correlations with HRQoL among Patients with CD

3.3. Predictors of Health-Related Quality of Life (HRQoL) in Patients with CD: A Comprehensive Regression Analysis

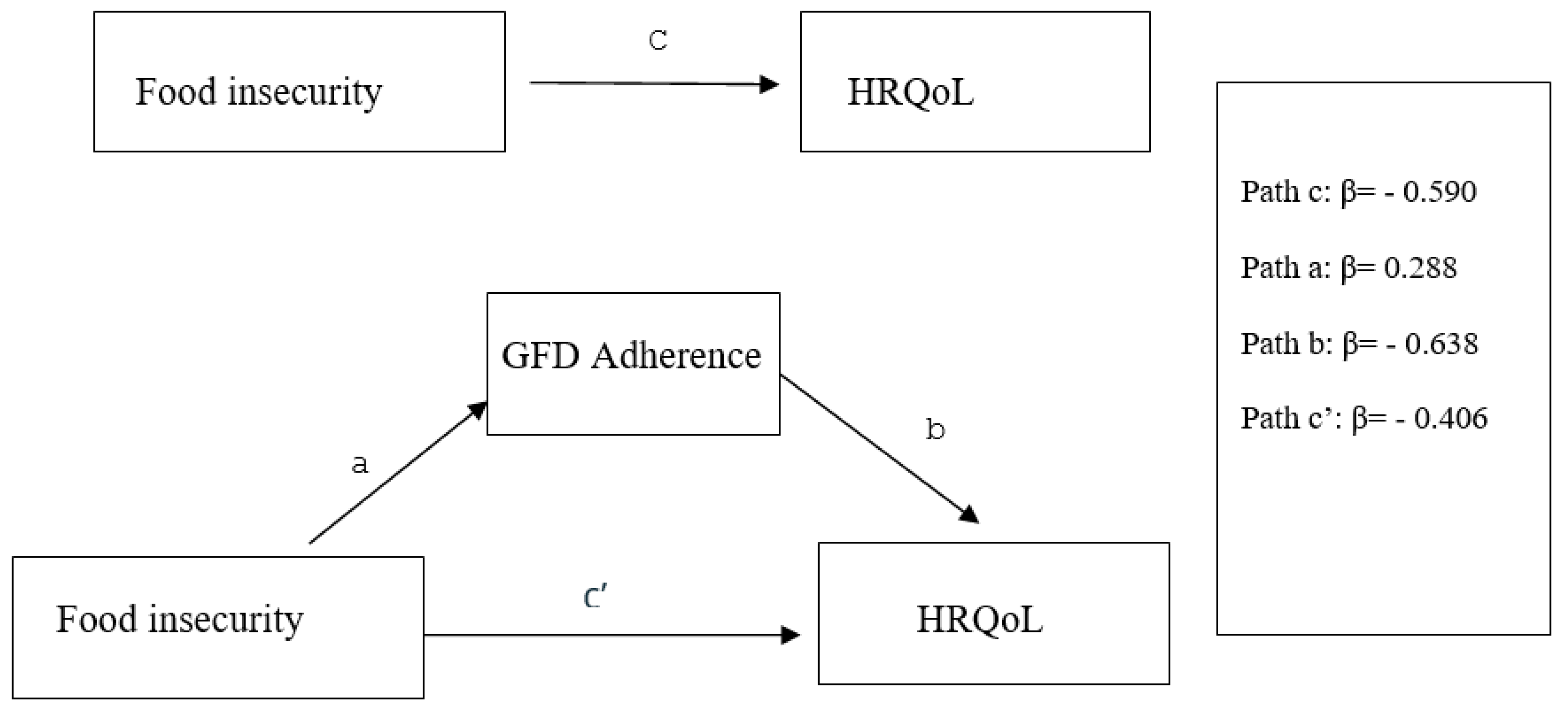

3.4. Mediation and Moderation in the Context of Food Insecurity’s (FI) Influence on Health-Related Quality of Life (HRQoL)

4. Discussion

5. Strength and Limitations

6. Conclusions and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Scherf, K.A.; Catassi, C.; Chirdo, F.; Ciclitira, P.J.; Feighery, C.; Gianfrani, C.; Koning, F.; Lundin, K.E.A.; Schuppan, D.; Smulders, M.J.M.; et al. Recent Progress and Recommendations on Celiac Disease From the Working Group on Prolamin Analysis and Toxicity. Front. Nutr. 2020, 7, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caio, G.; Volta, U.; Sapone, A.; Leffler, D.A.; De Giorgio, R.; Catassi, C.; Fasano, A. Celiac disease: A comprehensive current review. BMC Med. 2019, 17, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, J.A.; Jeong, J.; Underwood, F.E.; Quan, J.; Panaccione, N.; Windsor, J.W.; Coward, S.; Debruyn, J.; Ronksley, P.E.; Shaheen, A.-A.; et al. Incidence of Celiac Disease Is Increasing Over Time: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2020, 115, 507–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aljada, B.; Zohni, A.; El-Matary, W. The Gluten-Free Diet for Celiac Disease and Beyond. Nutrients 2021, 13, 3993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bascuñán, K.A.; Vespa, M.C.; Araya, M. Celiac disease: Understanding the gluten-free diet. Eur. J. Nutr. 2017, 56, 449–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deepak, C.; Berry, N.; Vaiphei, K.; Dhaka, N.; Sinha, S.K.; Kochhar, R. Quality of life in celiac disease and the effect of gluten-free diet. JGH Open 2018, 2, 124–128. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Sunaid, F.F.; Al-Homidi, M.M.; Al-Qahtani, R.M.; Al-Ashwal, R.A.; Mudhish, G.A.; Hanbazaza, M.A.; Al-Zaben, A.S. The influence of a gluten-free diet on health-related quality of life in individuals with celiac disease. BMC Gastroenterol. 2021, 21, 330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muhammad, H.; Reeves, S.; Jeanes, Y.M. Identifying and improving adherence to the gluten-free diet in people with coeliac disease. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2019, 78, 418–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.; Singh, S.; Jairath, V.; Radulescu, G.; Ho, S.K.; Choi, M.Y. Food Insecurity Negatively Impacts Gluten Avoidance and Nutritional Intake in Patients With Celiac Disease. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2022, 56, 863–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wieser, H.; Segura, V.; Ruiz-Carnicer, Á.; Sousa, C.; Comino, I. Food Safety and Cross-Contamination of Gluten-Free Products: A Narrative Review. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siminiuc, R.; Ṭurcanu, D. Food security of people with celiac disease in the Republic of Moldova through prism of public policies. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 961827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elsahoryi, N.; Al-Sayyed, H.; Odeh, M.; McGrattan, A.; Hammad, F. Effect of COVID-19 on food security: A cross-sectional survey. Clin. Nutr. ESPEN 2020, 40, 171–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pourhoseingholi, M.A.; Vahedi, M.; Rahimzadeh, M. Sample size calculation in medical studies. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. Bed Bench 2013, 6, 14–17. [Google Scholar]

- Marques, B.; Azevedo, J.; Rodrigues, I.; Rainho, C.; Gonçalves, C. Food Insecurity Levels among University Students: A Cross-Sectional Study. Societies 2022, 12, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, S.M.; Soltanizadeh, N.; Mirmoghtadaee, P.; Banavand, P.; Mirmoghtadaie, L.; Shojaee-Aliabadi, S. Gluten-free products in celiac disease: Nutritional and technological challenges and solutions. J. Res. Med. Sci. 2018, 23, 109. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Baron, R.M.; Kenny, D.A. The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 51, 1173–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Violato, M.; Gray, A. The impact of diagnosis on health-related quality of life in people with coeliac disease: A UK population-based longitudinal perspective. BMC Gastroenterol. 2019, 19, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kasiulevičius, V.; Šapoka, V.; Filipavičiūtė, R. Sample size calculation in epidemiological studies. Gerontologija 2006, 7, 225–231. [Google Scholar]

- Patrick, D.; Erickson, P. Health Policy, Quality of Life: Health Care Evaluation and Resource Allocation; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meysamie, A.; Taee, F.; Mohammadi-Vajari, M.-A.; Yoosefi-Khanghah, S.; Emamzadeh-Fard, S.; Abbassi, M. Sample size calculation on web, can we rely on the results? J. Med. Stat. Inform. 2014, 2, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCrum-Gardner, E. Sample size and power calculations made simple. Int. J. Ther. Rehabil. 2010, 17, 10–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddad, C.; Sacre, H.; Obeid, S.; Salameh, P.; Hallit, S. Validation of the Arabic version of the “12-item short-form health survey” (SF-12) in a sample of Lebanese adults. Arch. Public Health 2021, 79, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leffler, D.A.; Dennis, M.; Edwards George, J.B.; Jamma, S.; Magge, S.; Cook, E.F.; Schuppan, D.; Kelly, C.P. A Simple Validated Gluten-Free Diet Adherence Survey for Adults with Celiac Disease. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2009, 7, 530–536.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naja, F.; Hwalla, N.; Fossian, T.; Zebian, D.; Nasreddine, L. Validity and reliability of the Arabic version of the Household Food Insecurity Access Scale in rural Lebanon. Public Health Nutr. 2015, 18, 251–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Degroot, A.M.B.; Dannenburg, L.; Vanhell, J.G. Forward and Backward Word Translation by Bilinguals. J. Mem. Lang. 1994, 33, 600–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ware, J.E.; Kosinski, M.; Keller, S.D. A 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey. Med. Care 1996, 34, 220–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manjunath, K.; Christopher, P.; Gopichandran, V.; Rakesh, P.; George, K.; Prasad, J.H. Quality of life of a patient with type 2 diabetes: A cross-sectional study in Rural South India. J. Fam. Med. Prim. Care 2014, 3, 396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis, 2nd ed.; A Regression-Based Approach; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Al Sarkhy, A.; El Mouzan, M.I.; Saeed, E.; Alanazi, A.; Alghamdi, S.; Anil, S.; Assiri, A. Clinical Characteristics of Celiac Disease and Dietary Adherence to Gluten-Free Diet among Saudi Children. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. Nutr. 2015, 18, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyarzún, A.; Nakash, T.; Ayala, J.; Lucero, Y.; Araya, M. Following Gluten Free Diet: Less Available, Higher Cost and Poor Nutritional Profile of Gluten-Free School Snacks. Int. J. Celiac Dis. 2016, 3, 102–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alimoradi, Z.; Kazemi, F.; Estaki, T. Household food security in Iran: Systematic review of Iranian articles. Adv. Nurs. Midwifery 2015, 24, 63–76. [Google Scholar]

- Khalifeh, F.; Riasatian, M.S.; Ekramzadeh, M.; Honar, N.; Jalali, M. Assessing the Prevalence of Food Insecurity among Children with Celiac Disease: A Cross-sectional Study. J. Food Secur. 2019, 7, 192–195. [Google Scholar]

- Taghdir, M.; Honar, N.; Mazloomi, S.M.; Sepandi, M.; Ashourpour, M.; Salehi, M. Dietary compliance in Iranian children and adolescents with celiac disease. J. Multidiscip. Healthc. 2016, 9, 365–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Case, S. The gluten-free diet: How to provide effective education and resources. Gastroenterology 2005, 128, S128–S134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, H.J.; Anderson, Z.; Ryu, D. Gluten Contamination in Foods Labeled as “Gluten Free” in the United States. J. Food Prot. 2014, 77, 1830–1834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biagi, F.; Bianchi, P.I.; Marchese, A.; Trotta, L.; Vattiato, C.; Balduzzi, D.; Brusco, G.; Andrealli, A.; Cisarò, F.; Astegiano, M.; et al. A score that verifies adherence to a gluten-free diet: A cross-sectional, multicentre validation in real clinical life. Br. J. Nutr. 2012, 108, 1884–1888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biagi, F.; Andrealli, A.; Bianchi, P.I.; Marchese, A.; Klersy, C.; Corazza, G.R. A gluten-free diet score to evaluate dietary compliance in patients with coeliac disease. Br. J. Nutr. 2009, 102, 882–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sdepanian, V.L.; Morais MB, d.e.; Fagundes-Neto, U. Doença celíaca: Avaliação da obediência à dieta isenta de glúten e do conhecimento da doença pelos pacientes cadastrados na Associação dos Celíacos do Brasil (ACELBRA). Arq. Gastroenterol. 2001, 38, 232–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halmos, E.P.; Deng, M.; Knowles, S.R.; Sainsbury, K.; Mullan, B.; Tye-Din, J.A. Food knowledge and psychological state predict adherence to a gluten-free diet in a survey of 5310 Australians and New Zealanders with coeliac disease. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2018, 48, 78–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hall, N.J.; Rubin, G.P.; Charnock, A. Intentional and inadvertent non-adherence in adult coeliac disease. A cross-sectional survey. Appetite 2013, 68, 56–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olsson, C.; Lyon, P.; Hörnell, A.; Ivarsson, A.; Sydner, Y.M. Food That Makes You Different: The Stigma Experienced by Adolescents with Celiac Disease. Qual. Health Res. 2009, 19, 976–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casella, S.; Zanini, B.; Lanzarotto, F.; Villanacci, V.; Ricci, C.; Lanzini, A. Celiac Disease in Elderly Adults: Clinical, Serological, and Histological Characteristics and the Effect of a Gluten-Free Diet. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2012, 60, 1064–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilppula, A.; Kaukinen, K.; Luostarinen, L.; Krekelä, I.; Patrikainen, H.; Valve, R.; Luostarinen, M.; Laurila, K.; Mäki, M.; Collin, P. Clinical benefit of gluten-free diet in screen-detected older celiac disease patients. BMC Gastroenterol. 2011, 11, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajpoot, P.; Sharma, A.; Harikrishnan, S.; Baruah, B.J.; Ahuja, V.; Makharia, G.K. Adherence to gluten-free diet and barriers to adherence in patients with celiac disease. Indian J. Gastroenterol. 2015, 34, 380–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hughey, J.J.; Ray, B.K.; Lee, A.R.; Voorhees, K.N.; Kelly, C.P.; Schuppan, D. Self-reported dietary adherence, disease-specific symptoms, and quality of life are associated with healthcare provider follow-up in celiac disease. BMC Gastroenterol. 2017, 17, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Hees, N.J.M.; Van der Does, W.; Giltay, E.J. Coeliac disease, diet adherence and depressive symptoms. J. Psychosom. Res. 2013, 74, 155–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sainsbury, K.; Marques, M.M. The relationship between gluten free diet adherence and depressive symptoms in adults with coeliac disease: A systematic review with meta-analysis. Appetite 2018, 120, 578–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pietzak, M.M. Follow-up of patients with celiac disease: Achieving compliance with treatment. Gastroenterology 2005, 128, S135–S141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeanes, Y. Cost, availability and nutritional composition comparison between gluten free and gluten containing food staples provided by food outlets and internet food delivery services between two areas of London with differing UK deprivation indices. In Coeliac UK Delegates Brochure; University of Roehampton: London, UK, 2018; Available online: http://bspghan.org.uk/documents/Abstract%20book_BSPGHAN%202018%20annual%20meeting (accessed on 20 June 2024).

- Singh, J.; Whelan, K. Limited availability and higher cost of gluten-free foods. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 2011, 24, 479–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barratt, S.M.; Leeds, J.S.; Sanders, D.S. Quality of life in Coeliac Disease is determined by perceived degree of difficulty adhering to a gluten-free diet, not the level of dietary adherence ultimately achieved. J. Gastrointestin. Liver Dis. 2011, 20, 241–245. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zarkadas, M.; Cranney, A.; Case, S.; Molloy, M.; Switzer, C.; Graham, I.D.; Butzner, J.D.; Rashid, M.; Warren, R.E.; Burrows, V. The impact of a gluten-free diet on adults with coeliac disease: Results of a national survey. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 2006, 19, 41–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aljahdali, A.A.; Na, M.; Leung, C.W. Food insecurity and health-related quality of life among a nationally representative sample of older adults: Cross-sectional analysis. BMC Geriatr. 2024, 24, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casellas, F.; Rodrigo, L.; Vivancos, J.L.; Riestra, S.; Pantiga, C.; Baudet, J.; Junquera, F.; Diví, V.P.; Abadia, C.; Papo, M.; et al. Factors that impact health-related quality of life in adults with celiac disease: A multicenter study. World J. Gastroenterol. 2008, 14, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rustagi, S.; Choudhary, S.; Khan, S.; Jain, T. Consequential Effect of Gluten-Free Diet on Health-Related Quality of Life in Celiac Populace-A Meta-Analysis. Curr. Res. Nutr. Food Sci. J. 2020, 8, 1025–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, A.D. Food Insecurity and Mental Health Status: A Global Analysis of 149 Countries. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2017, 53, 264–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, S.H.; Alqurneh, R.; Abu Sneineh, A.; Ghazal, B.; Agraib, L.; Abbasi, L.; Mazzawi, T.; Rifaei, S.M. The Prevalence of Anxiety and Depressive Symptoms among Patients with Celiac Disease in Jordan. Cureus 2023, 15, e39842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zysk, W.; Głąbska, D.; Guzek, D. Social and Emotional Fears and Worries Influencing the Quality of Life of Female Celiac Disease Patients Following a Gluten-Free Diet. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alahmari, T.M.; Asiri, A.J.; Bilali, R.M.; Qahtani, A.S.; Alqarni, M.A.; Almalwi, F.A. Quality of Life and Wellbeing of Patients with Celiac Disease in Aseer Region of Saudi Arabia. Int. J. Med. Res. Prof. 2018, 4, 170–174. [Google Scholar]

- Pourhoseingholi, M.A.; Rostami-Nejad, M.; Barzegar, F.; Rostami, K.; Volta, U.; Sadeghi, A.; Honarkar, Z.; Salehi, N.; Asadzadeh-Aghdaei, H.; Baghestani, A.R.; et al. Economic burden made celiac disease an expensive and challenging condition for Iranian patients. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. Bed Bench 2017, 10, 258–262. [Google Scholar]

| Variable | Categories | N (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Age * | 28.52 ± 8.48 | |

| Gender | Male | 321 (27.6) |

| Female | 841 (72.4) | |

| Marital status | Single without spouse | 703 (60.5) |

| Married | 459 (39.5) | |

| Monthly income (JOD) ** | <500 | 672 (57.8) |

| 500–700 | 292 (25.1) | |

| >700 | 198 (17.0) | |

| Education level | Secondary school or lower | 635 (54.6) |

| Undergraduate degree | 479 (41.2) | |

| Postgraduate degree | 48 (4.1) | |

| Body Mass Index * | 20.16 ± 2.3 | |

| Normal | 270 (23.2) | |

| Overweight | 832 (71.6) | |

| Obese | 60 (5.2) | |

| Variable | FI | GFD Adherence |

|---|---|---|

| FI | - | 0.489 ** |

| GFD Adherence | 0.489 ** | - |

| HRQoL | −0.367 ** | −0.353 ** |

| Variable | Unstandardized Coefficients | Standardize Coefficients | p-Value | 95.0% Confidence Interval for B | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE | Beta | Lower Bound | Upper Bound | ||

| (Constant) | 42.336 | 3.089 | 0.000 | 36.275 | 48.397 | |

| Age | 0.052 | 0.041 | 0.038 | 0.210 | −0.029 | 0.133 |

| BMI | 0.134 | 0.142 | 0.026 | 0.346 | −0.145 | 0.412 |

| Gender (female) | −4.619 | 0.743 | −0.178 | ≤0.001 | −6.077 | −3.162 |

| Marital status (married) | −2.700 | 0.755 | −0.114 | ≤0.001 | −4.181 | −1.220 |

| Monthly income (JOD) | ||||||

| 500–700 | 2.370 | 0.788 | 0.088 | 0.003 | 0.824 | 3.916 |

| >700 | 6.681 | 0.938 | 0.216 | ≤0.001 | 4.840 | 8.522 |

| Education level | ||||||

| Undergraduate | −0.520 | 0.740 | −0.022 | 0.482 | −1.971 | 0.931 |

| Postgraduate | 2.778 | 1.725 | 0.048 | 0.108 | −0.607 | 6.163 |

| Effect a, Variable | R2 | F | β | p-Value |

| Direct effect of mediator (GFD adherence on HRQoL) | 0.213 | 62.56 | −0.638 | ≤0.0001 |

| Direct effect of the predictor (FI) on mediator (GFD adherence) | 0.246 | 94.15 | 0.288 | ≤0.0001 |

| Total effect of predictor (FI) on HRQoL | 0.178 | 28.97 | −0.509 | ≤0.0001 |

| Direct effect of predictor (FI) on HRQoL with inclusion of the mediator (GFD adherence t) | 0.213 | 62.56 | −0.406 | ≤0.0001 |

| β | 95% CL | p-Value | ||

| Indirect predictor (Food insecurity) on HRQoL | −0.184 | −0.236 | −0.134 | ≤0.0001 |

| a Variable | R2 | β | SE | t | p-Value | 95.0% Confidence Interval | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower Bound | Upper Bound | ||||||

| Direct effect of predictor (FI) on HRQoL | 0.213 | −0.399 | 0.173 | −2.30 | 0.021 | −0.739 | −0.095 |

| Direct effect of a moderator (GFD Adherence | 0.213 | −0.629 | 0.236 | −2.66 | 0.007 | −1.092 | −0.166 |

| Direct interactions effect (FI × GFD Adherence) on HRQoL | 0.213 | −0.0005 | 0.011 | −0.043 | 0.965 | −0.0224 | 0.021 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Elsahoryi, N.A.; Ibrahim, M.O.; Alhaj, O.A. Adherence to the Gluten-Free Diet Role as a Mediating and Moderating of the Relationship between Food Insecurity and Health-Related Quality of Life in Adults with Celiac Disease: Cross-Sectional Study. Nutrients 2024, 16, 2229. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16142229

Elsahoryi NA, Ibrahim MO, Alhaj OA. Adherence to the Gluten-Free Diet Role as a Mediating and Moderating of the Relationship between Food Insecurity and Health-Related Quality of Life in Adults with Celiac Disease: Cross-Sectional Study. Nutrients. 2024; 16(14):2229. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16142229

Chicago/Turabian StyleElsahoryi, Nour Amin, Mohammed Omar Ibrahim, and Omar Amin Alhaj. 2024. "Adherence to the Gluten-Free Diet Role as a Mediating and Moderating of the Relationship between Food Insecurity and Health-Related Quality of Life in Adults with Celiac Disease: Cross-Sectional Study" Nutrients 16, no. 14: 2229. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16142229

APA StyleElsahoryi, N. A., Ibrahim, M. O., & Alhaj, O. A. (2024). Adherence to the Gluten-Free Diet Role as a Mediating and Moderating of the Relationship between Food Insecurity and Health-Related Quality of Life in Adults with Celiac Disease: Cross-Sectional Study. Nutrients, 16(14), 2229. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16142229