The Effects of Dietary Intervention and Macrophage-Activating Factor Supplementation on Cognitive Function in Elderly Users of Outpatient Rehabilitation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

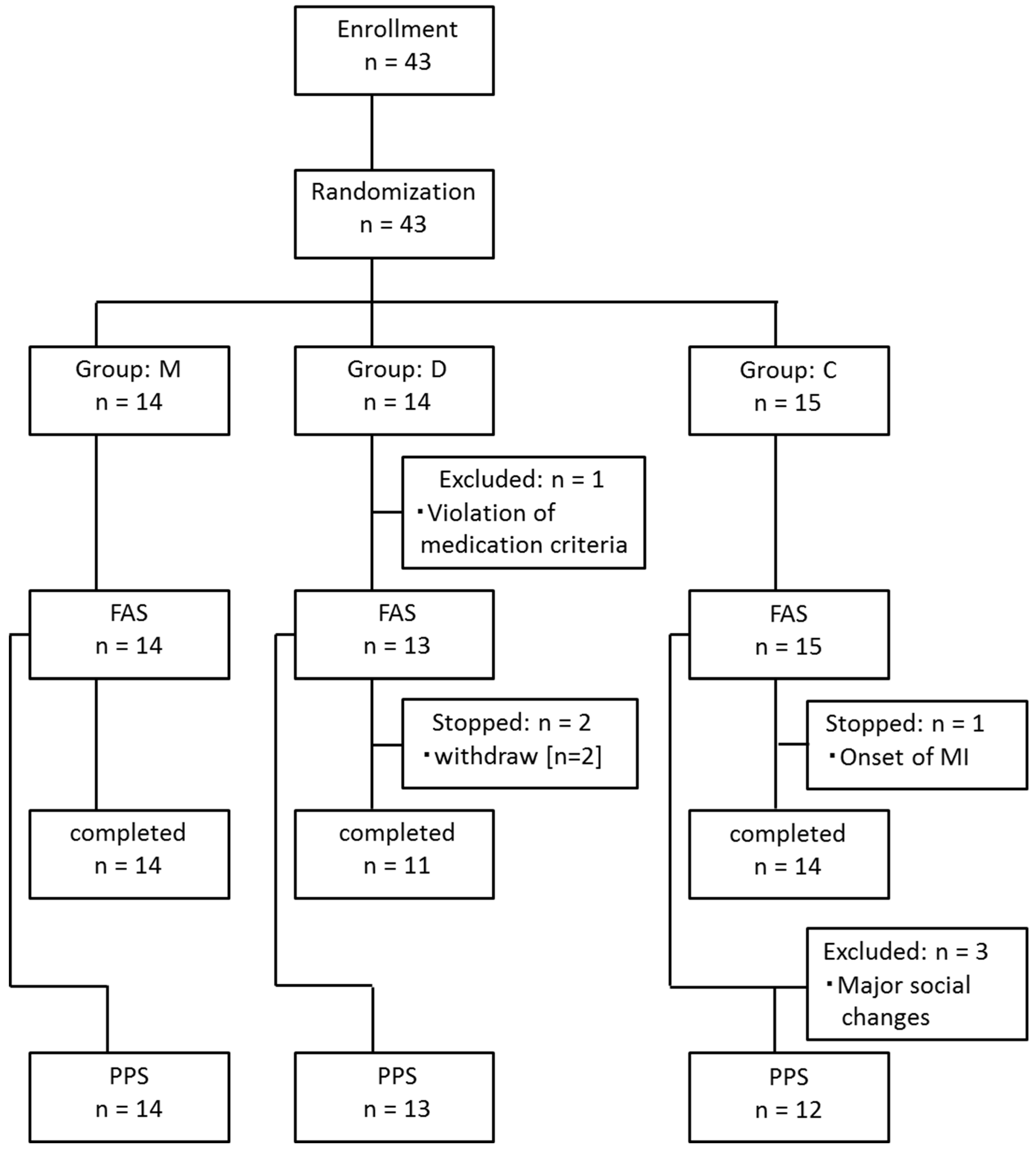

2.1. Study Design and Participants

2.2. Randomization

2.3. Dietary Guidance

2.4. Calculation of AGEs in the Diet

2.5. Cognitive Function Assessment

2.6. AGE Measurement

2.7. Plasma Ratio of Amyloid-β40 to Amyloid-β42

2.8. Sample Size

2.9. Statistical Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rao, R.V.; Subramaniam, V.K.G.; Gregory, J.; Bredesen, A.; Coward, C.; Okada, S.; Kelly, L.; Bredesen, D.E. Rationale for a multi-factorial approach for the reversal of cognitive decline in Alzheimer’s disease and MCI: A review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 1659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troups, K.; Hathaway, A.; Gordon, D.; Chung, H.; Raji, C.; Boyd, A.; Hill, B.D.; Hausman-Cohen, S.; Attarha, M.; Chwa, W.J.; et al. Precision medicine approach to Alzheimer’s disease: Successful pilot project. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2022, 88, 1411–1421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Ansari, V.A.; Mahmood, T.; Ahsan, F.; Rufaida, W.; Shariq, M.; Parveen, S.; Maheshwari, S. Receptor for advanced glycation end products: Dementia and cognitive impairment. Drug Res. 2023, 73, 247–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salter, M.W.; Stevens, B. Microglia emerge as central players in brain disease. Nat. Med. 2017, 23, 1018–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salter, M.W.; Beggs, S. Sublime microglia: Expanding roles for the guardians of the CNS. Cell 2014, 158, 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GBD 2019 Dementia Forecasting Collaborators. Estimation of the global prevalence of dementia in 2019 and forecasted prevalence in 2050: An analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Public Health 2022, 2, e105–e125. [Google Scholar]

- Bredesen, D.E.; Amos, E.C.; Canick, J.; Ackerley, M.; Raji, C.; Fiala, M.; Ahdidan, J. Reversal of cognitive decline in Alzheimer’s disease. Aging 2016, 8, 1250–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tobin, M.K.; Musaraca, K.; Disouky, A.; Bennett, D.A.; Arfanakis, K.; Lazarov, O. Human hippocampal neurogenesis persists in aged adults and Alzheimer’s disease patients. Cell Stem Cell 2019, 24, 974–982.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNamara, N.B.; Munro, D.A.D.; Bestard-Cuche, N.; Uyeda, A.; Bogie, J.F.J.; Hoffmann, A.; Holloway, R.K.; Molina-Gonzalez, I.; Askew, K.E.; Mitchell, S.; et al. Microglia regulate central nervous system myelin growth and integrity. Nature 2023, 613, 120–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tay, T.L.; Savage, J.C.; Hui, C.W.; Bisht, K.; Tremblay, M.-È. Microglia across the lifespan: From origin to function in brain development, plasticity and cognition. J. Physiol. 2016, 595, 1929–1945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, S.; Dissing-Olesen, L.; Stevens, B. New insights on the role of microglia in synaptic pruning in health and disease. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2016, 36, 128–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nimmerjahn, A.; Kirchhoff, F.; Helmchen, F. Resting microglial cells are highly dynamic surveillants of brain parenchyma in vivo. Science 2005, 308, 1314–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marín-Teva, J.L.; Cuadros, M.A.; Martín-Oliva, D.; Navascués, J. Microglia and neuronal cell death. Neuron Glia Biol. 2011, 7, 25–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sierra, A.; Encinas, J.M.; Deudero, J.J.P.; Chancey, J.H.; Enikolopov, G.; Overstreet-Wadiche, L.S.; Tsirka, S.E.; Maletic-Savatic, M. Microglia shape adult hippocampal neurogenesis through apoptosis-coupled phagocytosis. Cell Stem Cell 2010, 7, 483–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, A.M.; Davey, K.; Tsartsalis, S.; Khozoie, C.; Famcy, N.; Tang, S.S.; Liaptsi, E.; Weinert, M.; McGarry, A.; Muirhead, R.C.J.; et al. Diverse human astrocyte and microglial transcriptional responses to Alzheimer’s pathology. Acta Neuropathol. 2022, 143, 75–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonneh-Barkay, D.; Bissel, S.J.; Kofler, J.; Starkey, A.; Wang, G.; Wiley, C.A. Astrocyte and macrophage regulatio of YKL-40 expression and cellular response in neuroinflammation. Brain Pathol. 2012, 22, 530–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagasawa, H.; Uto, Y.; Sasaki, H.; Okamura, N.; Murakami, A.; Kubo, S.; Kirk, K.L.; Hori, H. Gc protein (vitamin D-binding protein): Gc genotyping and GcMAF precursor activity. Anticancer Res. 2005, 25, 3689–3695. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Thyer, L.; Ward, E.; Smith, R.; Fiore, M.G.; Magherini, S.; Branca, J.J.V.; Morucci, G.; Gulisano, M.; Ruggiero, M.; Pacini, S. A novel role for a major component of the vitamin D axis: Vitamin D binding protein-derived macrophage activating factor induces human breast cancer cell apoptosis through stimulation of macrophages. Nutrients 2013, 5, 2577–2589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamamoto, N.; Kumashiro, R. Conversion of vitamin D3 binding protein (group-specific component) to a macrophage activating factor by the stepwise action of beta-galactosidase of B cells and sialidase of T cells. J. Immunol. 1993, 151, 2794–2802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurashiki, Y.; Kagusa, H.; Yagi, K.; Kinouchi, T.; Sumiyoshi, M.; Miyamoto, T.; Shimada, K.; Kitazato, K.T.; Uto, Y.; Takagi, Y. Role of post-ischemic phase-dependent modulation of anti-inflammatory M2-type macrophages against rat brain damage. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2023, 43, 531–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kagusa, H.; Yamaguchi, I.; Shono, K.; Mizobuchi, Y.; Shikata, E.; Matsuda, T.; Miyamoto, T.; Hara, K.; Kitazato, K.T.; Uto, Y.; et al. Differences in amyloid-β and tau/p-tau deposition in blood-injected mouse brains using micro-syringe to mimic traumatic brain microhemorrhages. J. Chem. Neuroanat. 2023, 130, 102258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siniscalco, D.; Bradstreet, J.J.; Cirillo, A.; Antonucci, N. The in vitro GcMAF effects on endocannabinoid system transcriptionomics, receptor formation, and cell activity of autism-derived macrophages. J. Neuroinflamm. 2014, 11, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inui, T.; Katuura, G.; Kubo, K.; Kuchiike, D.; Chenery, L.; Uto, Y.; Nishikata, T.; Mette, M. Case report: GcMAF treatment in a patient with multiple sclerosis. Anticancer Res. 2016, 36, 3771–3774. [Google Scholar]

- Monnier, V.M. Nonenzymatic glycosylation, the Maillard reaction and the aging process. J. Gerontol. 1990, 45, B105–B111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamagishi, S.-I.; Fukami, K.; Matsui, T. Evaluation of tissue accumulation levels of advanced glycation end products by skin autofluorescence: A novel marker of vascular complications in high-risk patients for cardiovascular disease. Int. J. Cardiol. 2015, 185, 263–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamagishi, S.-I. Role of advanced glycation end products (AGEs) in osteoporosis in diabetes. Curr. Drug Targets 2011, 12, 2096–2102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamagishi, S.-I. Potential clinical utility of advanced glycation end product cross-link breakers in age- and diabetes-associated disorders. Rejuvenation Res. 2012, 15, 564–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamagishi, S.-I.; Ueda, S.; Okuda, S. Food-derived advanced glycation end products (AGEs): A novel therapeutic target for various disorders. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2007, 13, 2832–2836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isami, F.; West, B.J.; Nakajima, S.; Yamagishi, S.-I. Association of advanced glycation end products, evaluated by skin autofluoresecence, with lifestlyle habits in a general Japanese population. J. Int. Med. Res. 2018, 46, 1043–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uribarri, J.; Woodruff, S.; Goodman, S.; Cai, W.; Chen, X.; Pyzik, R.; Yong, A.; Striker, G.E.; Vlassara, H. Advanced glycation end products in foods and a practical guide to their reduction in the diet. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2010, 110, 911–916.e12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, B.J.; Uwaya, A.; Isami, F.; Deng, S.; Nakajima, S.; Jensen, C.J. Antiglycation activity of iridoids and their food sources. Int. J. Food Sci. 2014, 2014, 276950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shankle, W.R.; Mangrola, T.; Chan, T.; Hara, J. Development and validation of the memory performance index: Reducing measurement error in recall tests. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2009, 5, 295–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafii, M.S.; Taylor, C.; Coutinho, A.; Kim, K.; Galasko, D. Comparison of the memory performance index with standard neuropsychological measures of cognition. Am. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. Other Dement. 2011, 26, 235–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyder, P.J.; Jackson, C.E.; Petersen, R.C.; Khachaturian, A.R.; Kaye, J.; Albeeert, M.S.; Weintraub, S. Assessment of cognition in mild cognitive impairment: A comparative study. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2011, 7, 338–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shankle, W.R.; Romney, A.K.; Hara, J.; Fortier, D.; Dick, M.B.; Chen, J.M.; Chan, T.; Sun, X. Methods to improve the detection of mild cognitive impairment. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 4919–4924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trenkle, D.L.; Shankle, W.R.; Azen, S.P. Detecting cognitive impairment in primary care: Performance assessment of three screening instruments. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2007, 11, 323–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, A.; Sugimura, M.; Nakano, S.; Yamada, T. The Japanese MCI screen for early detection of Alzheimer’s disease and related disorders. Am. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. Other Dement. 2008, 23, 162–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meerwaldt, R.; Graaf, R.; Oomen, P.H.N.; Links, T.P.; Japer, J.J.; Alderson, N.L.; Thorpe, S.R.; Baynes, J.W.; Gans, R.O.B.; Smit, A.J. Simple non-invasive assessment of advanced glycation endproduct accumulation. Diabetologia 2004, 47, 1324–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bos, D.C.; de Ranitz-Greven, W.L.; de Valk, H.W. Advanced glycation end products, measured as skin autofluorescence and diabetes complications: A systematic review. Diabetes. Technol. Ther. 2011, 13, 773–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corstjens, H.; Dicanio, D.; Muizzuddin, N.; Neven, A.; Sparacio, R.; Declercq, L.; Maes, D. Glycation associated skin autofluorescence and skin elasticity are related to chronological age and body mass index of healthy subjects. Exp. Gerontol. 2008, 43, 663–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obayashi, H.; Nakano, K.; Shigeta, H.; Yamaguchi, M.; Yoshimori, K.; Fukui, M.; Fujii, M.; Kitagawa, Y.; Nakamura, N.; Nakamura, K.; et al. Formation of crossline as a fluorescent advanced glycation end product in vitro and in vivo. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1996, 226, 37–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamagishi, S.-I.; Matsui, T. Pathologic role of dietary advanced glycation end products in cardiometabolic disorders, and therapeutic intervention. Nutrition 2016, 32, 157–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Waateringe, R.P.; Fokkens, B.T.; Slagter, S.N.; van der Klauw, M.M.; van Vliet-Ostaptchouk, J.V.; Graaf, R.; Paterson, A.D.; Smit, A.J.; Lutgers, H.L.; Wolffenbuttel, B.H.R. Skin autofluorescence predicts incident type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease and mortality in the general population. Diabetologia 2019, 62, 269–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schindler, S.E.; Bollinger, J.G.; Ovod, V.; Mawuenyega, K.G.; Li, Y.; Gordon, B.A.; Holtzman, D.M.; Morris, J.C.; Benzinger, T.L.S.; Xiong, S.; et al. High-precision plasma β-amyloid 42/40 predicts current and future brain amyloidosis. Neurology 2019, 93, e1647–e1659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ngandu, T.; Lehtisalo, J.; Solomon, A.; Levalahti, E.; Ahtiluoto, S.; Antikainen, R.; Backman, L.; Hanninen, T.; Jula, A.; Laatikainen, T.; et al. A 2 year multidomain intervention of diet, exercise, cognitive training, and vascular risk monitoring versus control to prevent cognitive decline in at-risk elderly people (FINGER): A randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2015, 385, 2255–2263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scarmeas, N.; Luchsinger, J.A.; Schupf, N.; Brickman, A.M.; Cosentino, S.; Tang, M.X.; Stern, Y. Physical activity, diet, and risk of Alzheimer disease. JAMA 2009, 302, 627–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Group M | Group D | Group C | ASD | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (in FAS) | 14 | 13 | 15 | ||

| Gender [n, %] | 0.224 | ||||

| Male | 5, 35.7% | 5, 38.5% | 7, 46.7% | ||

| Female | 9, 64.3% | 8, 61.5% | 8, 53.3% | ||

| Age [years] | mean ± SD | 80.8 ± 10.3 | 78.5 ± 10.1 | 77.8 ± 6.8 | 0.342 |

| Years of education [years] | mean ± SD | 12.1 ± 1.8 | 12.7 ± 2.1 | 12.2 ± 2.2 | 0.307 |

| Nursing care level [n, %] | 0.411 | ||||

| Support Needed | 11, 78.6% | 10, 76.9% | 9, 60.0% | ||

| Care Needed | 3, 21.4% | 3, 23.1% | 6, 40.0% | ||

| Support: level 1 | 3, 21.4% | 0, 0.0% | 2, 13.3% | ||

| Support: level 2 | 8, 57.1% | 10, 76.9% | 7, 46.7% | ||

| Care: level 1 | 0, 0.0% | 1, 7.7% | 0, 0.0% | ||

| Care: level 2 | 1, 7.1% | 2, 15.4% | 3, 20.0% | ||

| Care: level 3 | 2, 14.3% | 0, 0.0% | 2, 13.3% | ||

| Care: level 4 | 0, 0.0% | 0, 0.0% | 1, 6.7% | ||

| Diabetes mellitus | yes | 2, 14.3% | 5, 38.5% | 6, 42.9% | 0.667 |

| Current smoker | yes | 0, 0.0% | 0, 0.0% | 1, 6.7% | 0.379 |

| Baseline parameters | |||||

| MCIS | mean ± SD | 46.4 ± 16.5 | 47.2 ± 12.2 | 44.2 ± 13.9 | 0.230 |

| AGE | mean ± SD | 2.7 ± 0.6 | 2.5 ± 0.5 | 2.7 ± 0.5 | 0.269 |

| Aβ40/42 | mean ± SD | 10.1 ± 2.0 | 9.7 ± 1.7 | 10.5 ± 1.7 | 0.483 |

| dietary AGEs | mean ± SD | 11,914 ± 4632 | 12,287 ± 7108 | 11,530 ± 3513 | 0.135 |

| Calories in diet | mean ± SD | 1564 ± 272 | 1626 ± 297 | 1550 ± 272 | 0.266 |

| Group M | Group D | Group C | p ** | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LSM | 95% CI | p * | LSM | 95% CI | p * | LSM | 95% CI | p * | M vs. C | D vs. C | M vs. D | |

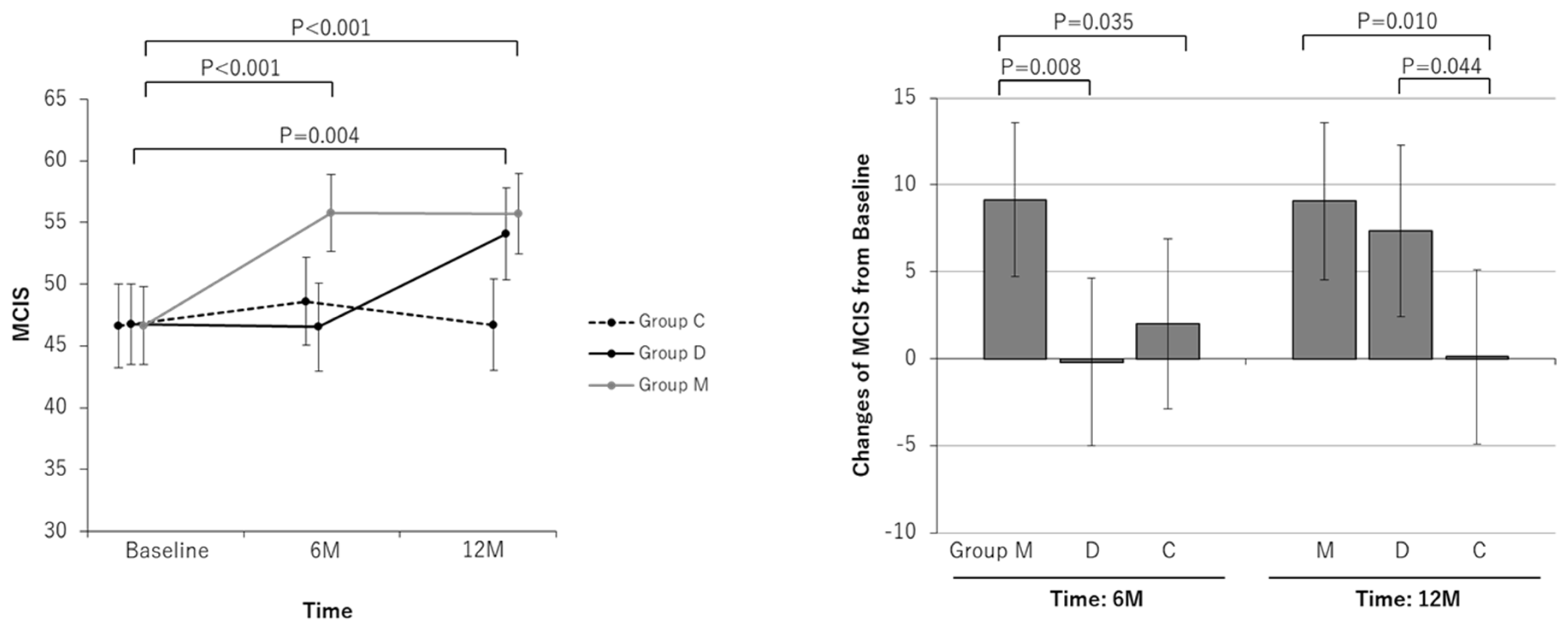

| MCIS | ||||||||||||

| Baseline | 46.65 | 43.51 to 49.79 | 46.73 | 43.47 to 49.99 | 46.62 | 43.22 to 50.01 | ||||||

| At 6-month | 55.79 | 52.65 to 58.93 | 46.52 | 42.98 to 50.06 | 48.61 | 45.06 to 52.15 | ||||||

| Change at 6-month | 9.14 | 4.70 to 13.58 | <0.001 | −0.21 | −5.03 to 4.60 | 0.933 | 1.99 | −2.91 to 6.90 | 0.422 | 0.035 | 0.526 | 0.008 |

| At 12-month | 55.71 | 52.45 to 58.97 | 54.09 | 50.37 to 57.81 | 46.71 | 42.99 to 50.44 | ||||||

| Change at 12-month | 9.06 | 4.53 to 13.59 | <0.001 | 7.36 | 2.42 to 12.30 | 0.005 | 0.10 | −4.93 to 5.13 | 0.969 | 0.010 | 0.044 | 0.624 |

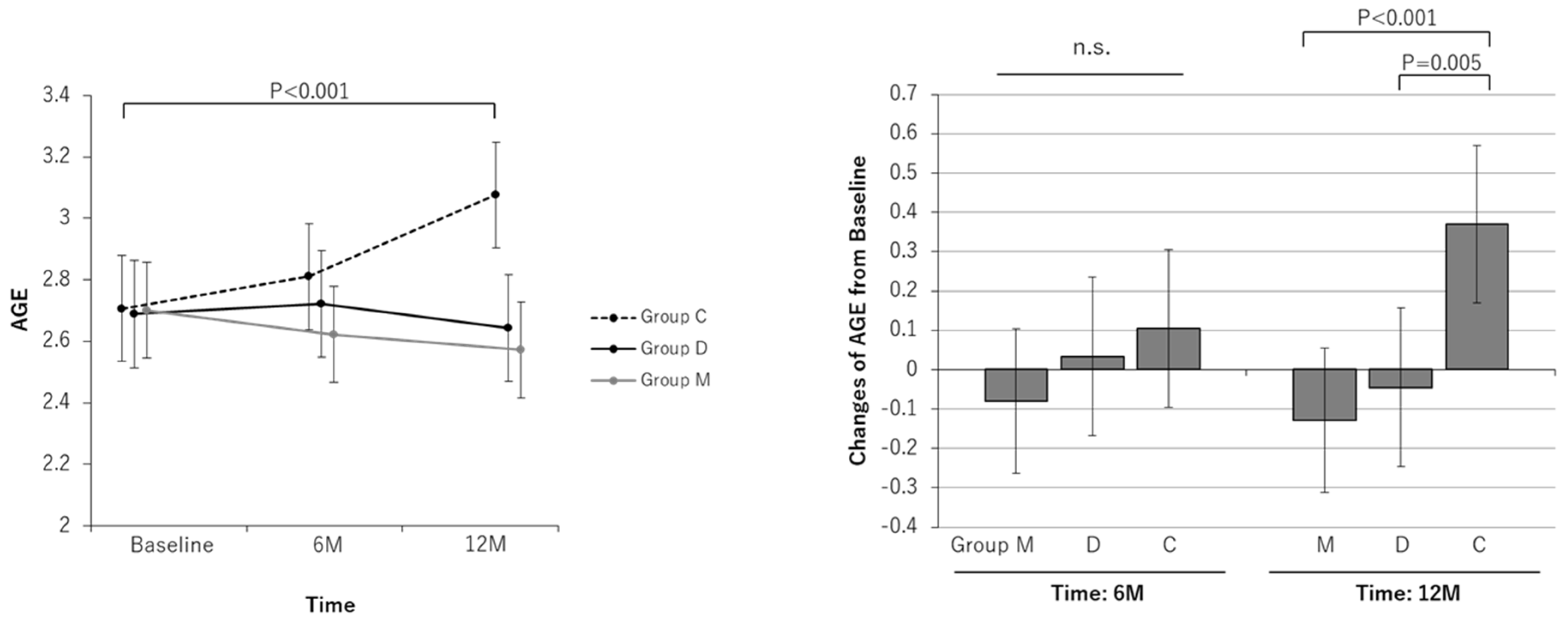

| AGE | ||||||||||||

| Baseline | 2.70 | 2.54 to 2.86 | 2.69 | 2.51 to 2.86 | 2.71 | 2.53 to 2.88 | ||||||

| At 6-month | 2.62 | 2.47 to 2.78 | 2.72 | 2.55 to 2.90 | 2.81 | 2.64 to 2.98 | ||||||

| Change at 6-month | −0.08 | −0.26 to 0.10 | 0.391 | 0.03 | −0.17 to 0.23 | 0.740 | 0.10 | −0.10 to 0.31 | 0.300 | 0.181 | 0.616 | 0.410 |

| At 12-month | 2.57 | 2.42 to 2.73 | 2.64 | 2.47 to 2.82 | 3.08 | 2.90 to 3.25 | ||||||

| Change at 12-month | −0.13 | −0.31 to 0.05 | 0.164 | −0.05 | −0.25 to 0.16 | 0.656 | 0.37 | 0.17 to 0.57 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.005 | 0.538 |

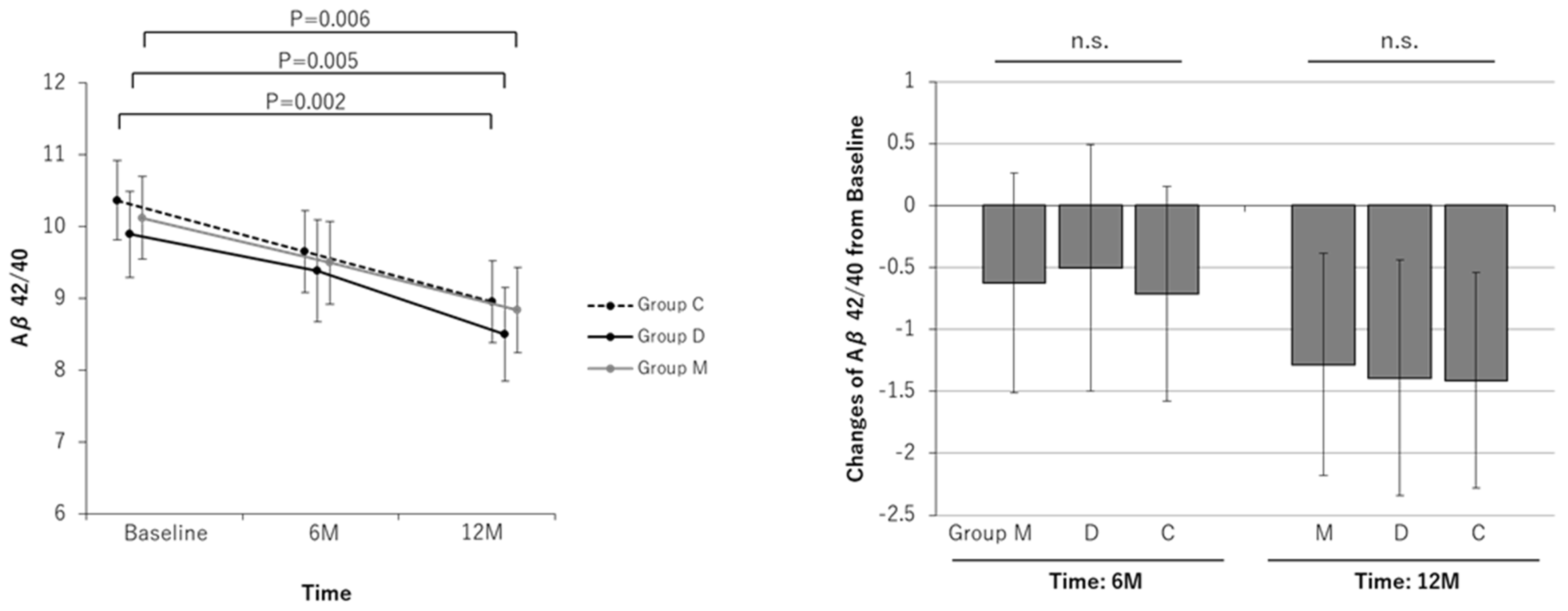

| Aβ40/42 | ||||||||||||

| Baseline | 10.12 | 9.55 to 10.69 | 9.89 | 9.29 to 10.49 | 10.36 | 9.81 to 10.92 | ||||||

| At 6-month | 9.50 | 8.92 to 10.07 | 9.39 | 8.68 to 10.09 | 9.65 | 9.08 to 10.22 | ||||||

| Change at 6-month | −0.63 | −1.51 to 0.26 | 0.163 | −0.50 | −1.50 to 0.49 | 0.316 | −0.71 | −1.58 to 0.15 | 0.106 | 0.889 | 0.754 | 0.856 |

| At 12-month | 8.84 | 8.25 to 9.43 | 8.50 | 7.85 to 9.15 | 8.95 | 8.38 to 9.53 | ||||||

| Change at 12-month | −1.28 | −2.18 to −0.38 | 0.006 | −1.39 | −2.34 to −0.44 | 0.005 | −1.41 | −2.28 to −0.54 | 0.002 | 0.839 | 0.975 | 0.871 |

| dietary AGEs | ||||||||||||

| Baseline | 12,003 | 10,775 to 13,232 | 12,043 | 10,717 to 13,370 | 11,821 | 10,592 to 13,050 | ||||||

| At 6-month | 10,975 | 9747 to 12,203 | 9665 | 8062 to 11,268 | 10,893 | 9620 to 12,166 | ||||||

| Change at 12-month | −1029 | −3044 to 986 | 0.307 | −2378 | −4724 to −32 | 0.047 | −928 | −2968 to 1112 | 0.363 | 0.944 | 0.352 | 0.383 |

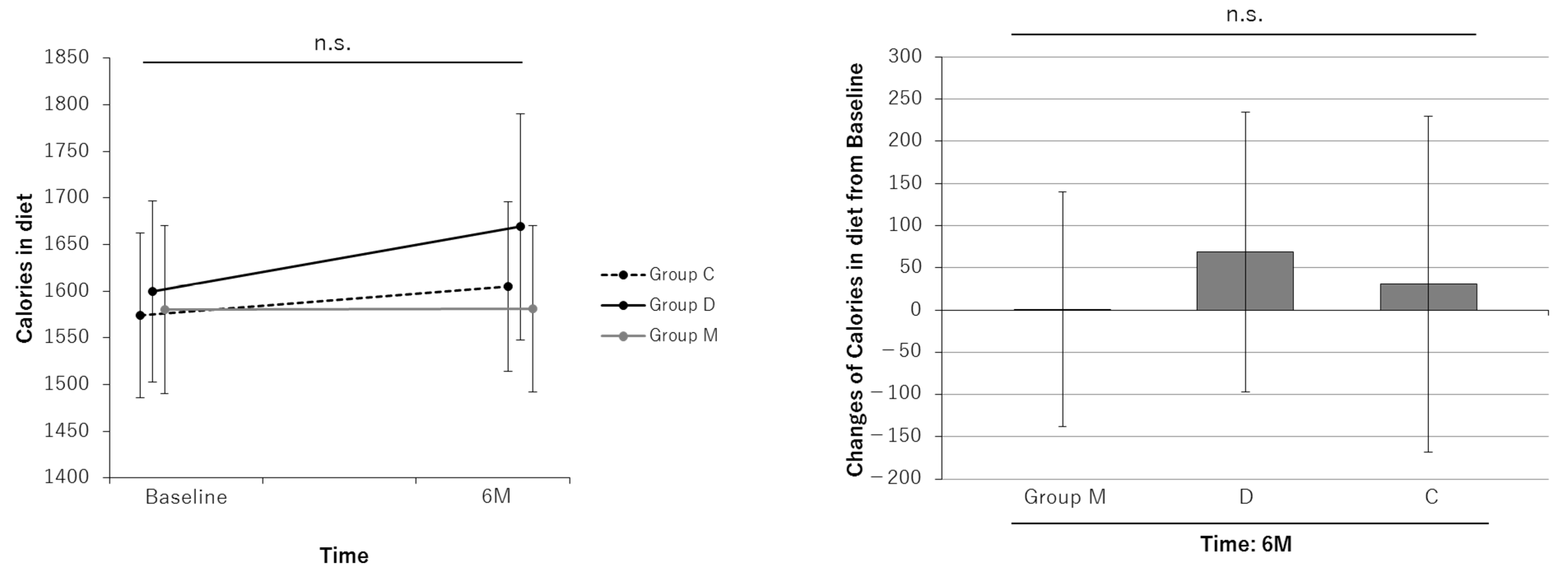

| Calories, daily | ||||||||||||

| Baseline | 1580 | 1490 to 1670 | 1600 | 1503 to 1698 | 1574 | 1486 to 1661 | ||||||

| At 6-month | 1581 | 1492 to 1672 | 1669 | 1548 to 1790 | 1605 | 1514 to 1695 | ||||||

| Change at 6-month | 1 | −138 to 142 | 0.980 | 69 | −97 to 235 | 0.410 | 31 | −168 to 106 | 0.651 | 0.765 | 0.726 | 0.538 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Uchiyama-Tanaka, Y.; Yamakage, H.; Inui, T. The Effects of Dietary Intervention and Macrophage-Activating Factor Supplementation on Cognitive Function in Elderly Users of Outpatient Rehabilitation. Nutrients 2024, 16, 2078. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16132078

Uchiyama-Tanaka Y, Yamakage H, Inui T. The Effects of Dietary Intervention and Macrophage-Activating Factor Supplementation on Cognitive Function in Elderly Users of Outpatient Rehabilitation. Nutrients. 2024; 16(13):2078. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16132078

Chicago/Turabian StyleUchiyama-Tanaka, Yoko, Hajime Yamakage, and Toshio Inui. 2024. "The Effects of Dietary Intervention and Macrophage-Activating Factor Supplementation on Cognitive Function in Elderly Users of Outpatient Rehabilitation" Nutrients 16, no. 13: 2078. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16132078

APA StyleUchiyama-Tanaka, Y., Yamakage, H., & Inui, T. (2024). The Effects of Dietary Intervention and Macrophage-Activating Factor Supplementation on Cognitive Function in Elderly Users of Outpatient Rehabilitation. Nutrients, 16(13), 2078. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16132078