Efficacy of a Food Supplement Containing Lactobacillus acidophilus LA14, Peptides, and a Multivitamin Complex in Improving Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease-Related Outcomes and Quality of Life of Subjects Showing Mild-to-Moderate Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease

Abstract

1. Introduction

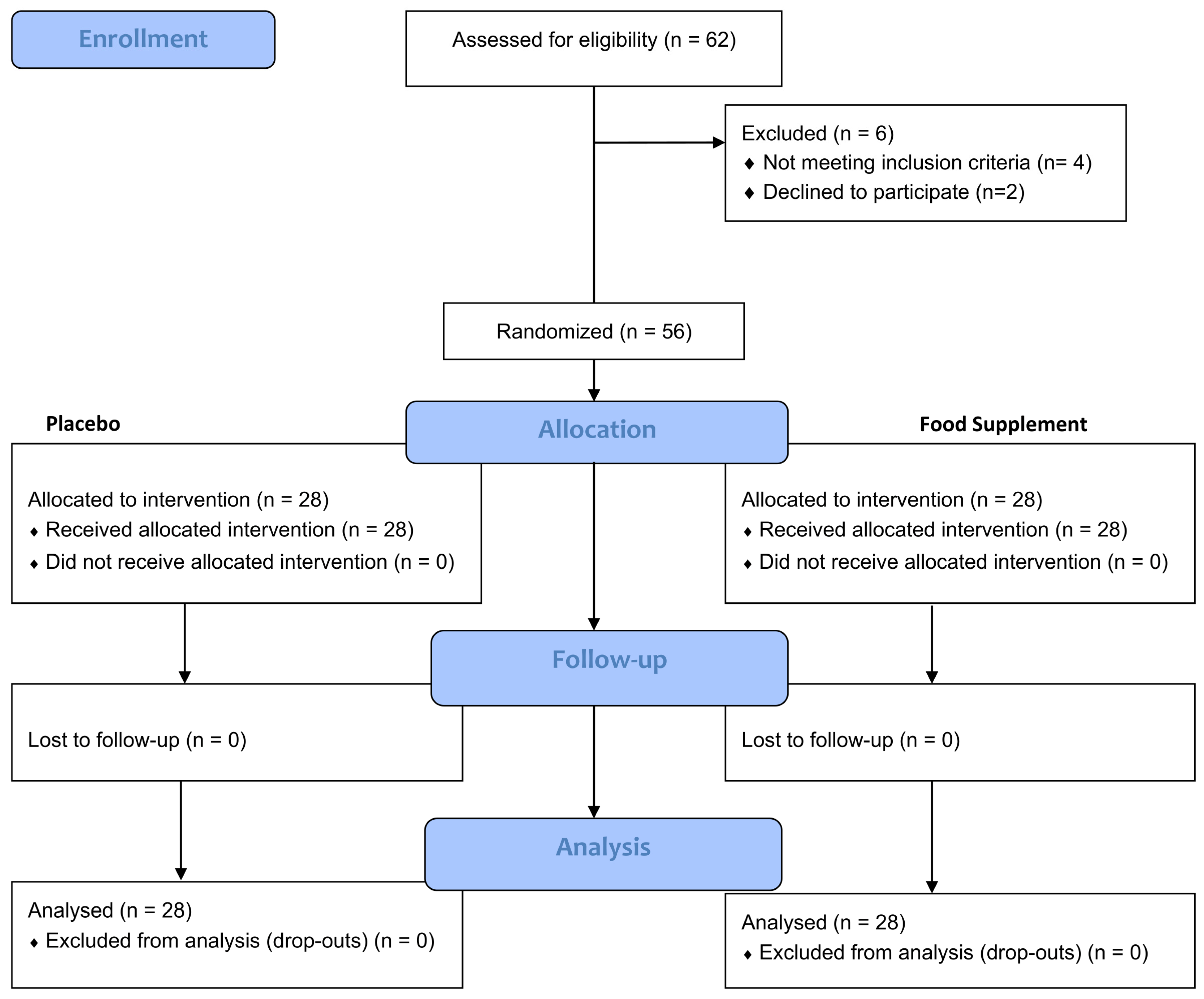

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Participants

2.2. Study Design

2.3. Primary and Secondary Outcomes of the Study

2.3.1. Quality of Life Questionnaire (GERD-QoL)

2.3.2. Self-Assessment Questionnaire

2.4. Products

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Heartburn Frequency and Severity

3.2. GERD-QoL Questionnaire

3.3. Self-Assessment Questionnaire

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Katz, P.O.; Dunbar, K.B.; Schnoll-Sussman, F.H.; Greer, K.B.; Yadlapati, R.; Spechler, S.J. ACG Clinical Guideline for the Diagnosis and Management of Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2022, 117, 27–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eusebi, L.H.; Ratnakumaran, R.; Yuan, Y.; Solaymani-Dodaran, M.; Bazzoli, F.; Ford, A.C. Global Prevalence of, and Risk Factors for, Gastro-Oesophageal Reflux Symptoms: A Meta-Analysis. Gut 2018, 67, 430–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Serag, H.B.; Sweet, S.; Winchester, C.C.; Dent, J. Update on the Epidemiology of Gastro-Oesophageal Reflux Disease: A Systematic Review. Gut 2014, 63, 871–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fass, R.; Frazier, R. The Role of Dexlansoprazole Modified-Release in the Management of Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease. Ther. Adv. Gastroenterol. 2017, 10, 243–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hom, C.; Vaezi, M.F. Extraesophageal Manifestations of Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease. Gastroenterol. Clin. N. Am. 2013, 42, 71–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antunes, C.; Aleem, A.; Curtis, S.A. Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Nirwan, J.S.; Hasan, S.S.; Babar, Z.-U.-D.; Conway, B.R.; Ghori, M.U. Global Prevalence and Risk Factors of Gastro-Oesophageal Reflux Disease (GORD): Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 5814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Savarino, V.; Marabotto, E.; Zentilin, P.; Demarzo, M.G.; de Bortoli, N.; Savarino, E. Pharmacological Management of Gastro-Esophageal Reflux Disease: An Update of the State-of-the-Art. Drug Des. Dev. Ther. 2021, 15, 1609–1621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patrick, L. Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease (GERD): A Review of Conventional and Alternative Treatments. Altern. Med. Rev. 2011, 16, 116–133. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zacny, J.; Zamakhshary, M.; Sketris, I.; van Zanten, S. Systematic review: The efficacy of intermittent and on-demand therapy with histamine. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2005, 21, 1299–1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salisbury, B.H.; Terrell, J.M. Antacids. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Lakananurak, N.; Pitisuttithum, P.; Susantitaphong, P.; Patcharatrakul, T.; Gonlachanvit, S. The Efficacy of Dietary Interventions in Patients with Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Intervention Studies. Nutrients 2024, 16, 464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, Z.; Spry, G.; Hoult, J.; Maimone, I.R.; Tang, X.; Crichton, M.; Marshall, S. What Is the Efficacy of Dietary, Nutraceutical, and Probiotic Interventions for the Management of Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease Symptoms? A Systematic Literature Review and Meta-Analysis. Clin. Nutr. ESPEN 2022, 52, 340–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, L.; Singh, R.; Ro, S.; Ghoshal, U.C. Gut microbiota dysbiosis in functional gastrointestinal disorders: Underpinning the symptoms and pathophysiology. JGH Open. 2021, 5, 976–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mandarino, F.V.; Sinagra, E.; Raimondo, D.; Danese, S. The Role of Microbiota in Upper and Lower Gastrointestinal Functional Disorders. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Souza, S.M.; Cundra, L.B.; Yoo, B.S.; Parekh, P.J.; Johnson, D.A. Microbiome and Gastroesophageal Disease: Pathogenesis and Implications for Therapy. Ann. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2020, 4, 020–033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackett, K.L.; Siddhi, S.S.; Cleary, S.; Steed, H.; Miller, M.H.; Macfarlane, S.; Macfarlane, G.T.; Dillon, J.F. Oesophageal bacterial biofilm changes in gastro-oesophageal reflux disease, barrett’s and oesophageal carcinoma: Association or causality? Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2013, 37, 1084–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corning, B.; Copland, A.P.; Frye, J.W. The Esophageal Microbiome in Health and Disease. Curr. Gastroenterol. Rep. 2018, 20, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.; Ouwehand, A.C. Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease and Probiotics: A Systematic Review. Nutrients 2020, 12, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Igarashi, M.; Nagano, J.; Tsuda, A.; Suzuki, T.; Koike, J.; Uchida, T.; Matsushima, M.; Mine, T.; Koga, Y. Correlation between the Serum Pepsinogen I Level and the Symptom Degree in Proton Pump Inhibitor-Users Administered with a Probiotic. Pharmaceuticals 2014, 7, 754–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keita, Å.V.; Söderholm, J.D. Mucosal Permeability and Mast Cells as Targets for Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 2018, 43, 66–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakae, H.; Tsuda, A.; Matsuoka, T.; Mine, T.; Koga, Y. Gastric Microbiota in the Functional Dyspepsia Patients Treated with Probiotic Yogurt. BMJ Open Gastroenterol. 2016, 3, e000109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, C.; Gleddie, S.; Xiao, C.-W. Soybean Bioactive Peptides and Their Functional Properties. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirata, Y.; Uchida, A. Clinical effects of Gastro AD in gastritis patients. Japn J. Med. Pharm. Sci. 2003, 49, 597–601. [Google Scholar]

- Fatani, A.; Vaher, K.; Rivero-Mendoza, D.; Alabasi, K.; Dahl, W.J. Fermented Soy Supplementation Improves Indicators of Quality of Life: A Randomized, Placebo-Controlled, Double-Blind Trial in Adults Experiencing Heartburn. BMC Res. Notes 2020, 13, 364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fraser, A.; Delaney, B.C.; Ford, A.C.; Qume, M.; Moayyedi, P. The Short-Form Leeds Dyspepsia Questionnaire validation study. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2007, 25, 477–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, R.; Junghard, O.; Dent, J.; Vakil, N.; Halling, K.; Wernersson, B.; Lind, T. Development of the GerdQ, a tool for the diagnosis and management of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease in primary care. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2009, 30, 1030–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gatta, L.; Moayyedi, P.; Tosetti, C.; Vakil, N.; Ubaldi, E.; Barsanti, P.; Fiorini, G.; Castelli, V.; Gargiulo, C.; Lucarini, P.; et al. A validation study of the Italian Short-Form Leeds Dyspepsia Questionnaire. Intern. Emerg. Med. 2010, 5, 501–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peters, J.H. Surgical treatment of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2014, 10, 247–248. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Newberry, C.; Lynch, K. The Role of Diet in the Development and Management of Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease: Why We Feel the Burn. J. Thorac. Dis. 2019, 11 (Suppl. 12), S1594–S1601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belobrajdic, D.P.; James-Martin, G.; Jones, D.; Tran, C.D. Soy and Gastrointestinal Health: A Review. Nutrients 2023, 15, 1959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skoufou, M.; Tsigalou, C.; Vradelis, S.; Bezirtzoglou, E. The Networked Interaction between Probiotics and Intestine in Health and Disease: A Promising Success Story. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hungin, A.P.S.; Mitchell, C.R.; Whorwell, P.; Mulligan, C.; Cole, O.; Agréus, L.; Fracasso, P.; Lionis, C.; Mendive, J.; Philippart de Foy, J.-M.; et al. Systematic Review: Probiotics in the Management of Lower Gastrointestinal Symptoms—An Updated Evidence-Based International Consensus. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2018, 47, 1054–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niu, H.-L.; Xiao, J.-Y. The efficacy and safety of probiotics in patients with irritable bowel syndrome: Evidence based on 35 randomized controlled trials. Int. J. Surg. 2020, 75, 116–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mekonnen, S.A.; Daniel Merenstein, D.; Fraser, C.M.; Marco, M.L. Molecular mechanisms of probiotic prevention of antibiotic-associated diarrhea. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2020, 61, 226–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Homan, M.; Orel, R. Are Probiotics Useful in Helicobacter Pylori Eradication? World J. Gastroenterol. 2015, 21, 10644–10653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, X.; Zhu, M.; He, Y.; Wang, T.; Tian, D.; Shu, J. The impacts of probiotics in eradication therapy of Helicobacter pylori. Arch. Microbiol. 2022, 204, 692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Lee, M.; Kim, D.; Kim, H.; Jo, S.; Kim, O.-K.; Lee, J. Gastro-Protective Effect of Fermented Soybean (Glycine max (L.) Merr.) in a Rat Model of Ethanol/HCl-Induced Gastric Injury. Nutrients 2022, 14, 2079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barchi, A.; Massimino, L.; Mandarino, F.V.; Vespa, E.; Sinagra, E.; Almolla, O.; Passaretti, S.; Fasulo, E.; Parigi, T.L.; Cagliani, S.; et al. Microbiota profiling in esophageal diseases: Novel insights into molecular staining and clinical outcomes. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2023, 23, 626–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

| Heartburn Frequency | ||||

| Placebo | Food Supplement | |||

| Time | Score | Tx − T0 | Score | Tx − T0 |

| T0 | 1.90 ± 0.1 | 1.77 ± 0.1 | ||

| T14 | 1.78 ± 0.1 | −0.12 ± 0.08 | 1.30 ± 0.1 *** | −0.47 ± 0.09 # |

| T28 | 1.88 ± 0.1 | −0.01 ± 0.09 | 1.24 ± 0.1 *** | −0.53 ± 0.08 ### |

| Heartburn Severity | ||||

| Placebo | Food Supplement | |||

| Time | Score | Tx − T0 | Score | Tx − T0 |

| T0 | 2.17 ± 0.1 | 2.20 ± 0.1 | ||

| T14 | 2.06 ± 0.1 | −0.10 ± 0.08 | 1.83 ± 0.1 ** | −3.7 ± 0.11 |

| T28 | 2.16 ± 0.1 | −0.01 ± 0.09 | 1.60 ± 0.1 *** | −6.1 ± 0.10 ### |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tursi, F.; Benedetto, E.; Spina, A.; De Ponti, I.; Amone, F.; Nobile, V. Efficacy of a Food Supplement Containing Lactobacillus acidophilus LA14, Peptides, and a Multivitamin Complex in Improving Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease-Related Outcomes and Quality of Life of Subjects Showing Mild-to-Moderate Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease. Nutrients 2024, 16, 1759. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16111759

Tursi F, Benedetto E, Spina A, De Ponti I, Amone F, Nobile V. Efficacy of a Food Supplement Containing Lactobacillus acidophilus LA14, Peptides, and a Multivitamin Complex in Improving Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease-Related Outcomes and Quality of Life of Subjects Showing Mild-to-Moderate Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease. Nutrients. 2024; 16(11):1759. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16111759

Chicago/Turabian StyleTursi, Francesco, Edoardo Benedetto, Amelia Spina, Ileana De Ponti, Fabio Amone, and Vincenzo Nobile. 2024. "Efficacy of a Food Supplement Containing Lactobacillus acidophilus LA14, Peptides, and a Multivitamin Complex in Improving Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease-Related Outcomes and Quality of Life of Subjects Showing Mild-to-Moderate Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease" Nutrients 16, no. 11: 1759. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16111759

APA StyleTursi, F., Benedetto, E., Spina, A., De Ponti, I., Amone, F., & Nobile, V. (2024). Efficacy of a Food Supplement Containing Lactobacillus acidophilus LA14, Peptides, and a Multivitamin Complex in Improving Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease-Related Outcomes and Quality of Life of Subjects Showing Mild-to-Moderate Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease. Nutrients, 16(11), 1759. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16111759